Abstract

Fuel price increases have long been a contentious issue in Indonesia, sparking intense public and political debates. This study examines how digital media, particularly Kompas.com and Tempo.co, shape public discourse on fuel price hikes through mediatization. Using discourse network analysis, this study compares the political narratives surrounding fuel price increases during the administrations of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2013) and Joko Widodo (2022). The findings reveal a shift in dominant discourse—opposition to price hikes was prominent in both periods, with government authority and economic justification emphasized in 2013, whereas concerns over rising living costs and social unrest dominated in 2022. This study highlights how mediatization has transformed policymaking from deliberative discussions into fragmented media battles, where digital platforms amplify competing narratives rather than facilitating consensus. Kompas.com predominantly featured counter-discourses, while Tempo.co exhibited stronger pro-government narratives in 2013. This study suggests that while digital media plays a crucial role in shaping policy perceptions, it does not necessarily translate into policy influence. It contributes to the broader understanding of the media’s role in policy debates. It underscores the need for more strategic government communication to manage public expectations and mitigate political unrest surrounding fuel price adjustments.

1. Introduction

Effective communication is a critical agenda for government administration, serving not only to absorb public aspirations but also to convey political messages and obtain feedback regarding governance (Hyland-Wood et al., 2021). Political communication by the government is an interactive arena of symbolic exchange between the mandate holders (government) and the mandate givers (citizens). In modern governance, ensuring mutual understanding between government and people is challenging, as meanings are dynamically interpreted and reinterpreted (Blumer, 1986; Denzin, 2016; Low, 2019). Assessing the effectiveness of government communication involves various methods, typically ranging from very difficult to straightforward achievements (Sanina et al., 2017; Strömbäck & Kiousis, 2020). Moreover, the rise in digital media has fundamentally altered the political communication landscape, blurring the lines between traditional top-down messaging and participatory public discourse. Scholars argue that disrupted, networked public spheres in the digital environment require rethinking how information flows and influence operates, underscoring the need to adapt political communication strategies to this new media reality (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018).

In the Indonesian context, three types of political communication issues are notably challenging: sectarian issues (SARA), increased prices of essential goods (especially fuel), and terminated social aid. Communicating fuel price increases effectively remains complex in the post-reform era. For decades, Indonesia kept fuel prices low through government subsidies; thus, any hike (i.e., subsidy reduction) is politically sensitive, often provoking public anger and protests. Firstly, fuel is a strategic energy source vital for achieving national economic goals (Sa’adah et al., 2017; Chelminski, 2018). Fuel price hikes can trigger inflation, hinder economic growth, and worsen poverty by raising transportation and production costs. Since 2004, Indonesia has been a net oil importer (despite once being a major OPEC producer), increasing domestic demand and adding fiscal strain. This context complicates price hike decisions (Kurniawan & Managi, 2018), as leaders must balance budget pressures against the risk of public backlash.

The policy of increasing fuel prices has been a contentious economic and political issue throughout Indonesian history, spanning from President Soekarno to President Joko Widodo (Wenger, 2023). Only President BJ Habibie refrained from raising fuel prices during his tenure. Historically, maintaining the stability of the State Revenue and Expenditure Budget (APBN) has driven fuel price increases across various administrations. However, we hypothesize that over time, the discourse around fuel price hikes will shift from an economic justification to a more fragmented, populist focus, particularly with the rise in digital platforms. This shift is grounded in network theory (Castells, 2012), which suggests that digital platforms facilitate the fragmentation of public discourse, allowing multiple actors with varying interests and political affiliations to amplify competing narratives. Through digital media, these actors—from political elites to grassroots movements—can bypass traditional media filters, allowing more populist, emotionally charged, and polarized narratives to flourish.

This transition from an economic rationale to socio-political framing aligns with mediatization theory (Hjarvard, 2008; Altheide, 2016), which emphasizes the role of media in reframing political issues to fit more personal, affective, and ideologically driven frames. Whereas government actors and economists typically justify fuel price hikes through technical arguments (such as fiscal policy and global oil price fluctuations), digital platforms increasingly emphasize fairness, inequality, and public accountability, resonating more with the general public’s grievances. Thus, as social media amplifies populist rhetoric and encourages participation from diverse actors, the discourse shifts to reflect broader socio-political concerns, moving beyond purely economic justifications.

Our research has found that no literature discusses the discourse on rising oil prices using discourse network analysis (DNA). This method combines network analysis with content analysis to map relationships among policy actors and ideas. A study by Abzianidze (2020) uses discourse network analysis to explore the in-group/out-group split in ideological and political discourse by using social network analysis to examine deeper discursive structures. This is achieved by analyzing the indirect relationships between actors based on their nationalist interactions with third parties. This shows that the actor structure of nationalist discourse conveys information about group polarization in Georgia, demonstrating that this discourse divide is a significant factor in nationalist discourse (Abzianidze, 2020). Research from Haunss et al. (2020) uses DNA to investigate the integration of machine learning in political claim annotation workflows to automate the annotation and analysis of large text corpora. The results show that newspaper articles contain considerable redundant information regarding political claim-making. Haunss et al. use the discourse network approach’s structural perspective to identify the leading actors and claims in a political debate. This opens up the possibility of annotation systems where human annotators no longer have to read the full text but only need to weed out false-positive AI suggestions (Haunss et al., 2020).

In contrast to previous DNA-based studies of political discourse—for example, Wallaschek et al. (2020), who analyzed EU solidarity narratives, and Bhattacharya (2020), who examined European Parliament debates—this study focuses on Indonesia’s fuel-price subsidy discourse. The unique aspect of this study lies in comparing political discourse construction in two different presidential periods, which shows how public discourse evolves. The findings of this study will contribute to the broader field of political communication by highlighting the role of digital media in shaping public discourse on controversial policy issues and providing insights for policymakers on the importance of effective communication strategies in garnering public support and reducing political unrest. This study aims to examine how mediatization via digital news media has shaped the political discourse on fuel price increases in Indonesia by comparing discourse networks from two key periods (2013 vs. 2022). We hypothesize that by 2022, amid deeper digital penetration, the fuel price hike discourse would feature more diverse actors and emphasize public grievances (e.g., living costs). In contrast, 2013 focused more on official government narratives and economic justifications.

The empirical expectations of this study—namely, that public discourse on fuel price increases becomes more fragmented and populist over time, shifting from economic justification to socio-political concerns—are grounded in mediatization theory and contemporary research on political communication. Mediatization theory posits that “media logic,” emphasizing immediacy, personalization, dramatization, and audience appeal, increasingly governs how political issues are constructed and understood (Hjarvard, 2008; Altheide, 2016; Hepp, 2020a). In Indonesia’s rapidly digitizing media environment, the proliferation of online news portals and social platforms has expanded discursive participation, enabling a broader set of actors—including non-elite voices—to contest policy narratives. This transformation is associated with the fragmentation of the public sphere, where traditional deliberative forums give way to digitally networked publics with divergent frames and interests (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018; Masduki, 2019). Consequently, rather than a centralized public discourse shaped predominantly by governmental or mainstream media actors, we expect to observe multiple, loosely connected discourse coalitions shaped by ideational affinity and platform dynamics.

This increasingly fragmented structure also fosters populist tendencies in discourse. As Mazzoleni (2008) and Altheide (2016) argue, the commercial imperatives of digital media often align with populist political communication, which simplifies complex issues into binary moral narratives, typically casting the people against the elite. Moreover, social media afford political actors and civil society figures the means to bypass institutional gatekeepers, introducing emotionally charged, populist rhetoric directly into the public debate (Udupa & McDowell, 2017). The result is a communication environment where populist narratives—marked by anti-elite sentiment, moral polarization, and appeals to common sense—can rapidly diffuse across networks. These patterns are increasingly “endemic” in online political spaces globally, and we expect that they similarly characterize the Indonesian digital discourse on fuel pricing, especially in the post-2019 period of intensified online political mobilization (Hepp, 2020b; Nugroho & Fitriawan, 2024).

Furthermore, the anticipated shift from economic reasoning to socio-political framing reflects the dynamic evolution of contentious policy discourse under conditions of media mediation. Initially, government actors legitimize unpopular economic reforms, such as fuel subsidy cuts, through technocratic arguments—focusing on fiscal pressure, global oil trends, or budgetary priorities (Chelminski, 2018; Sumantri, 2022). However, as public engagement increases and digital media amplifies alternative narratives, the discourse evolves to foreground socio-political impacts: rising costs of living, inequality, social unrest, and public accountability. This transition aligns with framing theory and deliberative policy models, which suggest that policy debates in a networked society increasingly revolve around value-based, affective, and symbolic frames rather than technical rationale (F. Fischer & Gottweis, 2012; Hajer & Wagenaar, 2003; Elster, 2002). Over time, enduring controversies like fuel pricing become not merely economic policy debates but discursive battlegrounds in broader struggles over justice, trust, and political legitimacy. Therefore, our analysis is guided by the expectation that the 2022 discourse would emphasize public grievances more than macroeconomic justification due to deeper mediatization and digital political engagement.

2. Literature Review

Public political discourse has rapidly shifted from traditional, analog forums to a digitally mediated environment. Indonesia’s swift internet and mobile communication development has expanded policy debates beyond village meetings and parliamentary hearings to online media platforms (Masduki, 2019). Consequently, media coverage and digital discussion forums now play a pivotal role in shaping how policy issues, such as fuel subsidy reforms, are framed and contested. Recent studies in political communication note that in this networked society, information flows are less top-down and more participatory, forcing governments to navigate a more complex media ecosystem to convey their messages (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018).

2.1. Public Communication and Deliberative Policy

Public communication discourse traditionally occurs in direct interpersonal settings or physical public discussion spaces, such as village deliberations or parliamentary forums. This process, known as “deliberation,” involves dialog between village leaders and the community and among the community members themselves (Antlöv & Wetterberg, 2021). In modern democracy, this dialog is reflected in forums within parliamentary institutions, where discussions between people’s representatives and the government occur, leading to public policy decisions (Slater & Wong, 2022). With the advent of mass media—print, radio, and television—the political communication arena expanded to include media platforms. Thus, political discourse on fuel price increases is predominantly mediated through mass media rather than institutional arenas like government-parliament discussions (Rahman et al., 2021). Digital technology revolutionized public communication discourse, transitioning from conventional mass media to internet-based platforms. Digital media extends human communication and shapes political reality, influencing decision-making processes (Kahan, 1999; McLuhan, 2002; Udupa & McDowell, 2017).

The media have evolved from merely transmitting information to actively shaping reality, as the constructionist perspective notes (Eriyanto, 2022). Digital technology has revolutionized public communication, extending human interaction into internet-based platforms and influencing decision-making processes (Udupa & McDowell, 2017). In the digital era, audiences are not just passive receivers of news; they also participate in and generate political content, blurring the line between media producers and consumers. Media outlets now not only select and report news but also define the actors and issues through framing, embedding their own organizational or political agendas in the coverage. This transformation means that media logic--the norms and formats by which the media operate—increasingly influences political discourse on public policies.

A new trend known as “deliberative policy” has emerged regarding policymaking. This model represents a networked society’s policy formulation process and challenges traditional, state-centric models (Hajer, 1997; Hajer & Wagenaar, 2003). The centralized policymaking model has faced numerous failures, particularly in a networked society where governance replaces government (Černý & Ocelík, 2020). Concepts such as network, complexity, and deliberation underpin the deliberative policy model, which emphasizes the inclusion of diverse actors and groups in the policy process. A deliberative model of public policy involves public participation as an existential component of the policy itself. Deliberative democracy underpins this model, which is defined as “decision-making by discussion among free and equal citizens” (Elster, 2002; O’Flynn, 2011; Bächtiger et al., 2018). Thomas Dye’s concept of community-based policy emphasizes policymaking based on community power rather than elite decisions (Dye, 1986; Howlett & Cashore, 2014).

Deliberative policy analysis, encompassing its concepts, policies, and implementation, originates from the understanding and practice of argumentative policy. It subsequently evolves into a discursive policy model and becomes more recognized, comprehended, and practiced as a deliberative one. F. Fischer and Gottweis (2012) highlight that argumentative policy models, constructed through language, result from argumentation. This deliberative policy framework accommodates a mediatized political reality, where media logic interacts to build a media ecology (F. Fischer & Gottweis, 2012; Bartels et al., 2020). Consequently, public policy manifests in a social reality where media complexity influences information, ideas, thought structures, and interactions among networked society actors that align with networked governance (Dwiyanto, 2004). As social reality becomes mediatized, media logic and ecology inevitably shape collective life.

2.2. Mediatization and Media Logic of Political Discourse

In recent years, we have witnessed the phenomenon of mass media playing a pivotal role in social and political life. Changes in practices, culture, and institutions are influenced significantly by the presence of the media, a condition referred to as “mediatization” (Lundby, 2014; Jansson, 2018). The advent of the internet, digital technology, and AI is intensifying this process, leading to what Hepp (2020a) calls “deep mediatization.” In a deeply mediatized society, the media act as a “powerful transformer” of social reality, permeating virtually all aspects of political and everyday life. Mediatization denotes the state when the media becomes an irresistible determinant of social reality. Pioneering communities lay the groundwork for the broader adoption of everyday practices related to specific technologies and the deepening of mediatization (Hepp, 2020b). New media surround us, constantly presenting messages and information, irrespective of our willingness to respond. This informational environment is significantly closer and more constitutive of communal life than previously considered (Webster, 2014). Esser and Strömbäck (2014) observe that mediatization is a dynamic, long-term process of social change that goes beyond the mere proliferation of messages. Recent work by Nugroho and Fitriawan (2024) likewise underscores how various media have become deeply integrated into various societal domains, amplifying their influence on politics.

Digital technology has evolved mediatization into deep mediatization, transforming objects like cars into media through digital connectivity. Digital media, being software-based and automatable through algorithms, now serves as a data generator, intensifying deep mediatization (Hepp et al., 2015; Hepp, 2020a; Kołodziejska et al., 2023). Media logic has developed into grammatical rules and perspectives for interpreting various objects and events, which audiences adopt to understand media experiences (Altheide, 2016). Media logic is essential in constructing social reality and guiding organizational behavior and societal norms. David Altheide’s concept of media logic (2016) provides a framework for studying how the media influences social reality using specific formats, styles, and narratives. Media logic implies that the media does not merely report news but constructs it by selecting, framing, and interpreting events according to their logic. This impacts audiences by shaping attitudes, opinions, beliefs, values, and behavior. Media logic also influences other social institutions, such as politics, religion, education, and sports, by affecting their communication and operation in media-saturated environments (Altheide, 2016). Altheide’s concept of media logic is particularly relevant to our study—it provides a framework for understanding how Indonesian news outlets (Kompas.com and Tempo.co)1 potentially filter and construct the fuel price issue using specific formats and narratives. In other words, media logic helps explain how these outlets’ choices in framing and style could shape public perceptions of the fuel price hike debate.

2.3. Theoretical Framework: From Media Logic to Networked Political Discourse

This study’s expectations—that political discourse surrounding fuel price increases becomes more fragmented and populist over time and shifts from economic to socio-political justifications—are conceptually grounded in mediatization, framing, and discourse network theories. Mediatization theory explains how media have moved beyond their traditional role as communication channels to become structuring forces in political and social life (Hjarvard, 2008; Esser & Strömbäck, 2014; Hepp, 2020a). Central to this is the notion of media logic: the narrative formats, presentation styles, and organizational imperatives of the media that privilege immediacy, personalization, dramatization, and audience appeal (Altheide, 2016; Jiang et al., 2022). In highly mediatized contexts, such as Indonesia’s digital media ecosystem, these logics increasingly influence how policy issues are framed and understood, often to the detriment of technocratic or deliberative discourse. Digital technologies and social platforms have further accelerated these dynamics, enabling a more participatory yet fragmented public sphere (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018; McDermott et al., 2025).

Rather than structured deliberation, the public debate increasingly occurs across dispersed, actor-driven networks (Markard et al., 2021). In this “networked society,” discourse is shaped not just by government officials or mainstream media but also by civil society actors, influencers, and ordinary citizens operating in digital environments. This shift aligns with theories of fragmented publics and disrupted communication flows in contemporary political communication research (Pfetsch, 2023). Such conditions also foster populist political communication. In mediatized digital environments, populist narratives—characterized by moral polarization, anti-elite sentiment, and emotive appeals—gain visibility and traction (Mazzoleni, 2008; Udupa & McDowell, 2017). Public grievances, particularly those involving perceived injustice or elite insensitivity (e.g., rising living costs), resonate more strongly than abstract economic arguments. As a result, we anticipate that in the 2022 discourse, socio-political concerns will become more central than macroeconomic rationales.

This discursive shift is also supported by deliberative policy models and framing theory, which posit that policy controversies in pluralistic societies evolve into symbolic contests over values, justice, and legitimacy (Hajer & Wagenaar, 2003; F. Fischer & Gottweis, 2012; Elster, 2002). Frames emphasizing lived experience and collective identity are more likely to dominate in contested digital debates, particularly when reinforced by real-world inequalities and political distrust. To analyze these dynamics, we employ discourse network analysis (DNA), which is informed by discourse network theory and grounded in network science (Leifeld & Haunss, 2012; M. Fischer & Leifeld, 2015; Eder, 2023). DNA conceptualizes public discourse as a relational network of actors and ideas, revealing how coalitions of meaning form, evolve, or disintegrate over time. This allows us to empirically trace the hypothesized shift from centralized, elite-driven discourse in 2013 to more fragmented, populist, and grievance-oriented narratives in 2022. By integrating these frameworks, our analysis explains how mediatization and media logic, combined with participatory digital environments, reshape the structure and content of contentious policy discourse. Rather than being isolated phenomena, Indonesia’s discursive fragmentation and politicization of fuel price debates are part of broader transformations in the mediatized public sphere.

3. Materials and Methods

The use of discourse network analysis (DNA) in this study is conceptually and methodologically grounded in network theory, a field that has become increasingly prominent in political communication scholarship. DNA conceptualizes public discourse as a relational network of nodes—policy actors, concepts, or both—and the ties that link them through shared positions, arguments, or co-mentions (Leifeld, 2017; Leifeld & Haunss, 2012). Rather than analyzing statements in isolation, DNA systematically maps how ideas and actors co-occur within political texts, thereby revealing structural patterns such as alignment, polarization, and coalition formation (M. Fischer & Leifeld, 2015). This approach integrates the strengths of both qualitative content analysis and quantitative network analysis, offering a multidimensional view of political discourse that captures its dynamic, relational character (Leifeld, 2020).

Methodologically, DNA proceeds by coding text sources—such as news articles or official statements—for actor claims and the concepts they reference and then transforming these data into matrices that can be analyzed using classic network measures such as centrality, density, and modularity (Leifeld, 2013). For example, if two actors frequently employ the same policy rationale (e.g., “reducing the state budget burden”), DNA links them as part of a discourse coalition; likewise, if various actors repeatedly invoke two concepts together, they are interpreted as forming a shared frame or policy narrative. These co-occurrence patterns mirror the logic of social network theory, where meaning and influence emerge through ties among actors and their communicative content (Ingold & Fischer, 2014). Thus, DNA aligns with the broader theoretical view that political communication is best understood not as a series of isolated positions but as an evolving network of relationships among actors and ideas.

Moreover, DNA was developed explicitly to extend network theory into discourse analysis, offering a formal method to trace how discursive alliances form, shift, and fragment over time (Leifeld & Haunss, 2012; F. Fischer, 2003). Its application in this study allows us to observe how the Indonesian fuel price discourse transformed across two administrations, mapping which actors were central and which ideas gained dominance or declined. In doing so, authors operationalize the foundational insights of network theory—such as connectivity, brokerage, and structural equivalence—within a discourse-based framework, which reinforces the study’s theoretical foundation and highlights the value of DNA in revealing how media-driven political discourse evolves under conditions of deepening digital mediatization.

3.1. Discourse Network Analysis

The study uses a qualitative method with a discourse network analysis (DNA) approach, which combines network analysis with qualitative content analysis. DNA systematically measures the beliefs and discourse of policy actors using text sources and formats the data to be compatible with policy network analysis, which facilitates the joint analysis of material policy networks (the “coordination layer”) and ideational networks among the same actors (the “discursive layer” or belief layer in subsystem politics). This method is implemented in the discourse network analyzer software, a qualitative content analysis package that enables the actor-based annotation of actors’ use of “concepts” (broadly understood as the content they discuss, including policy preferences or arguments) and the export of network data for statistical software and network analysis packages (Leifeld, 2020).

Wallaschek et al. (2020) conducted a discourse network analysis of the term solidarity in four major German newspapers (2008–2017), examining how various actors invoked solidarity across issues such as the Euro crisis, migration, political protest, and welfare, and distinguishing between solidarity among (internal bonds) and solidarity with (support for external groups). Bhattacharya (2020) applied discourse network analysis to the German Bundestag, comparing plenary speeches and MPs’ Explanations of Vote (EoVs) to show how party leaders’ control over speaking opportunities affects visible party unity, while internal dissent can emerge through the EoV format. These studies demonstrate how discourse network analysis can capture contested political narratives in both media and parliamentary arenas.

According to Leifeld (2020), DNA is one part of the conceptual understanding of political discourse, which is defined as verbal interactions between political actors in the policy domain. Regarding the discourse on subsidized fuel price increases, political actors make public claims about policies that depend on each other’s discourse, making discourse a dynamic network phenomenon that shapes political decisions. The DNA method begins by annotating actors’ statements in various sources, which in the context of this research means news in the mass media. After annotating actors’ statements in text sources, networks are created from the structured data, such as networks of congruence or conflict at the actor or concept level, networks of actor affiliations and concept attitudes, and longitudinal versions of such networks. The resulting network data reveals the essential properties of a debate, such as the structure of advocacy coalitions or discourse coalitions, polarization and consensus formation, and underlying endogenous processes such as popularity, reciprocity, or social balance (Leifeld, 2017; Bossner & Nagel, 2020; Ghinoi & Steiner, 2020).

DNA comprises the advocacy coalition framework (ACF) and discourse coalition framework (DCF). The ACF explains the policy formation process as a “battle” of various societal beliefs, where actors collaborate to accommodate their beliefs as policy (Eriyanto, 2022). The DCF, also known as argumentative discourse, examines how positive, negative, or neutral networks of actors that produce discourse are interconnected. This research employs the DCF analysis technique to explain the structure of actors’ positions in the network. We identify the process of public policy-making as a discourse battle by actors who build discourse to define a problem and gain public support. The actor’s victory is seen from the extent to which their discourse is accepted and becomes policy (Eriyanto, 2022).

In this study, we seek to explore the mediatization of political discourse on fuel price subsidies in Indonesia through a discourse network analysis of news coverage during SBY’s second term in 2013 and Jokowi’s second term in 2022. This is achieved by examining the logic of media in digital platforms to provide a comprehensive understanding of how political discourse is shaped, contested, and communicated to the public. This term was chosen because both periods featured significant subsidized fuel price hikes under different administrations, roughly a decade apart, allowing for a comparative view of mediatized discourse in two distinct political eras.

3.2. Data Collections

The data analyzed in this study includes discourse conveyed by actors in digital mass media, namely Kompas.com and Tempo.co. The selection of the mass media as a source of discourse data was determined by the press that Indonesians most widely consumed and the media present during the eras of President SBY and President Jokowi. The discourse data analyzed were taken from Kompas.com during 2013 (181 news items) and 2022 (524 news items) and Tempo.co during 2013 (324 news items) and 2022 (1.244 news items), with each exposure period spanning three months: before, during, and after the oil price increase. Data collection involved the following stages: searching for available data online; gathering data; pre-coding data by sorting discourse and actors using computer software; preparing basic coding using grounded research principles for comprehensive open coding; data cleaning for accuracy; manual and semi-manual data input carried out by eight coders over two months using the Visone application (version 2.28.2.) of the DNA instrument developed by Leifeld; data re-cleaning to ensure accuracy; initial DNA simulation; determining data processing limits with a threshold of 20 data points, using the degree of betweenness indicator, processing data from visone tables and iputting into Excel for transformation into Microsoft Office, and transforming the top 20 visone table data into visone visualization for analysis using the DNA approach.

4. Data Analysis Results

One of the stages of the DNA in this study involved comparing discourse surrounding the fuel price increases during the SBY (2013) and Jokowi (2022) administrations. We selected Kompas.com and Tempo.co as online mass media sources, assuming their political independence and lack of affiliation with specific political parties, thus providing reliable and accurate information. DNA outlines public policymaking as a contest among actors vying for the acceptance of dominant discourse as policy. According to Eriyanto (2022), there is a process in which the struggle will produce a “winner” with dominant actors and discourses. Network centrality measures can be analyzed to identify actors and discourses (concepts). Centrality refers to a metric that describes the dominance degree of an actor or concept. Three centralities can be used: degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality. In this study, the 20 most dominant actors were identified using the degree of centrality, also known as popularity, measured by the number of connections (links/edges) an actor has with other actors.

4.1. Discourse Network of Kompas.com

4.1.1. Dominant Actor and Discourse in Kompas.com in 2013

Processing the data from Kompas.com using DNA and determining the 20 strongest actors based on degree of centrality resulted in identifying the five most dominant actors. According to the DNA, their political tendencies -“Pros” and “Cons”—were marked. First, Syarief Hasan (government, Minister of Cooperatives and SMEs, Daily Chair of the Joint Secretariat, Democrat Party, Pros) had a centrality of 2.13%. Second, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (government, Deputy Governor of DKI, Gerindra Party, Cons) had a degree of centrality of 1.99%. Third, Said Iqbal (Civil Society President of the Confederation of Indonesian Trade Unions, Cons) had a degree of centrality of 1.99%. Fourth, Nurdin Tampubolon (politician, spokesperson for the Hanura Party Faction, Cons) had a centrality of 1.92%. Fifth, Agus Martowardojo (government, Minister of Finance, Pros) had a degree of centrality of 1.81%. Thus, among the 20 strongest actors, the discourse was dominated by actors against the policy (Cons) (n = 15) compared to those supporting it (Pros) (n = 5).

Among the 20 actors, 5 had a Pros sentiment, and 15 had a Cons sentiment. The discourse frequency indicates that Pros actors dominate among the 20 strongest actors, with 15 actors, or 75% of the total degree of centrality, compared to the presence of Cons actors (5 actors or 25% of the total degree of centrality). In Table 1, the data on closeness centrality describes how close an actor is to other actors in the network, indicating how easily or with difficulty others can reach an actor within the coalition (Eriyanto, 2022). The actor with the highest closeness centrality was Syarief Hasan (0.96%), followed by Said Iqbal and Nurdin Tampubolon (0.95%), Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (0.93%), and Ribka Tjiptaning and Rieke Diah Pitaloka (0.92%). The data on intermediary centrality describes an actor’s position as a link to other actors in the inter-coalition network (Eriyanto, 2022; McCulloh et al., 2013). The actor with the highest intermediary centrality was Syarief Hasan (7.26%), followed by Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (6.58%), Ribka Tjiptaning (5.33%), and Suswono (4.80%), which are moderate to bridge the contestation between coalitions.

Table 1.

Fuel price increase 2013 actor-based discourse ranking by degree of centrality in Kompas.com.

The DNA of Kompas.com data identified the 20 most vigorous discourses based on degree of centrality. The five most dominant discourses were government authority or “Kewenangan Pemerintah” (Pros): −6.36%; antipathy to fuel increases or “Antipati Kenaikan BBM” (Cons): −5.93%; Government Abuse or “Kesewenang-Wenangan Pemerintah” (Cons): −5.93%; increasing poverty or “Menambah Kemiskinan” (Cons): −5.51%; and policy ambiguity or “Ketidakjelasan Kebijakan” (Cons): −5.08%. The discourse on Kompas.com regarding the 2013 fuel increase was dominated by a larger rejecting coalition (n = 12; 0.67%) than those supporting it (n = 8; 0.43%).

According to Table 2, among the 20 main discourses, 12 were against the fuel increase, with a total discourse dominance of 47.45%, compared to 8 supporting discourses, with a total dominance of 24.15%. The supporting discourses primarily related to reducing the burden on the APBN, providing cheap transportation, promoting socialization, and supporting the government’s authority. The rejecting discourses highlighted increasing poverty, policy ambiguity, inappropriate momentum, and government abuse. Of the 20 discourses, 8 had a Pro sentiment, and 12 had a Con sentiment. The discourse frequency indicates that Cons discourses dominated among the 20 most vigorous discourses, with 12, or 60%, of the total degree of centrality, compared to Pros discourses with 8 or 40%.

Table 2.

Discourse ranking by degree of centrality in Kompas.com, 2013.

In Table 2, the data on closeness centrality describes how close a discourse is to other discourses in the network, indicating how easily others can reach a discourse within the coalition (Eriyanto, 2022). The discourse with the highest closeness centrality was government authority (0.92%), followed by antipathy to fuel increases (0.89%), government abuse (0.87%), increasing poverty (0.85%), and policy ambiguity (0.83%). The data in Table 2 on intermediary centrality describes a discourse’s position as a link to other discourses in the inter-coalition network (Eriyanto, 2022: 170, citing McCulloh et al., 2013). The discourse with the highest intermediary centrality was government authority (4.55%), followed by antipathy to fuel increases (3.98%), government abuse (3.65%), and increasing poverty (3.52%). Here, it can be observed that the counter-discourse dominates the discourse population with intermediate centrality, so the Pros discourse is relatively late in the contestation of the two coalitions–the same as the dominance of closeness centrality.

4.1.2. Dominant Cons Discourse in Kompas.com in 2022

The results from Kompas.com, analyzed using DNA with a focus on the 20 strongest discourses (or concepts) in terms of degree of centrality, reveal the following five most dominant discourses: increase in goods prices (Cons, 6.88%), social unrest (cons, 5.50%), increased poverty (Cons, 5.50%), mature socialization (Pros, 4.59%), and certainty of BLT compensation (Pros, 4.59%). From these findings, it can be concluded that Kompas.com’s discourse on the 2022 fuel price increase is dominated by a larger coalition of discourses that reject the policy (n = 11) than those that support it (n = 9).

The 20 main discourses in the fuel increase discourse coalition in the mediatization of Kompas.com are dominated by the opposing (Cons) discourse coalition, which comprises 11 discourses with a total share of 45.86%. The supporting (Pros) discourse coalition consists of eight discourses, with a total share of 31.65%, indicating a relatively small difference. The nine supporting (Pros) discourses related to fuel increases are as follows: certainty of BLT compensation, appropriate reasons, reducing the burden on the APBN (State Budget), approval of BLT compensation, encouragement to convert to energy other than oil, and appropriate compensation. Additionally, there are discourses beyond the issue of fuel increases that are political, such as: mature socialization, government authority, and certainty of protection for the lower-income people.

In Table 3, closeness centrality measures how close a discourse is to other discourses, indicating how easy or difficult it is for the discourse to be reached by other discourses in the network within the coalition (Eriyanto, 2022; McCulloh et al., 2013). The six discourses with the highest closeness centrality were increased prices of goods, social unrest, increasing poverty, certainty of BLT compensation, reducing purchasing power, and antipathy to fuel increases. The discourse population with high closeness centrality is dominated by counter-discourses, suggesting that Pros-discourses are relatively late in the contestation between the two coalitions. Data on intermediary centrality are presented in Table 4. Intermediary centrality measures an actor’s position as a link to other actors in the inter-coalition network (Eriyanto, 2022; McCulloh et al., 2013). The five discourses with the highest intermediary centrality were rising prices of goods, mature socialization, social upheaval, government authority, and increasing poverty. It can be observed that counter-discourses dominate the discourses with the highest intermediary centrality, which indicates that counter-discourses are more central in the network; at the same time, Pros-discourses emerge later in the contestation between the two coalitions, in contrast to the dominance seen in closeness centrality.

Table 3.

Discourse based on the ranking of the degree of centrality in Kompas.com, 2022.

Table 4.

Fuel price increase 2013 actor-based discourse ranking by degree of centrality in Tempo.co.

4.2. Discourse Network of Tempo.co

4.2.1. Dominant Actor and Discourse in Tempo.co in 2013

Processing the data from Tempo.co using DNA analysis with the aim of determining the 20 strongest actors in terms of the degree of centrality revealed the five most dominant actors, namely Jero Wacik (Government, Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Pros) 2.46%; Hanung Budya (Government, Director of Marketing and Commerce of PT Pertamina (Persero), Pros) 1.99%; Susilo Siswoutomo (Government, Deputy Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Commissioner of Pertamina, Pros) 1.64%; M. Chatib Basri (Government, Minister of Finance, Pros) 1.58%; and Djoko Suyanto (Government, Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, Pros) 1.38%. Overall, among the 20 strongest actors, the discourse was dominated by actors who were in favor (Pros) (n = 19) compared to those who were against (Cons) (n = 1).

Tempo.co raised a Pros discourse on the fuel increase policy. In fact, with near total dominance (95%), it implies a deliberate attempt by Tempo.co to align with the government’s policy. Tempo.co chose 14 Pros-government actors. Table 4 presents data on closeness centrality, which is a measure that describes how close an actor is to other actors and how easily an actor can be reached by other actors in the network within the coalition (Eriyanto, 2022; McCulloh et al., 2013). Five actors with the highest proximity centrality were found: Jero Wacik (government, Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Pros): 0.84%; Hanung Budya (government, director of marketing and commerce of pt pertamina (Persero) Pros): 0.74%; M. Chatib Basri (government, Minister of Finance, Pros): 0.72%; Susilo Siswoutomo (Government, Deputy Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Commissioner of Pertamina, Pros): 0.70; and Armida Alisjahbana (Government, Minister of National Development Planning/Bappenas, Pros): 0.70%.

Table 4 presents data on betweenness centrality, which is a measure that describes an actor’s position as a link to other actors in the network between coalitions (Eriyanto, 2022; McCulloh et al., 2013). It was found that the five actors with the highest intermediary centrality were Jero Wacik (Government, Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Pros) 18.24%; FX Hadi Rudyatmo (Government, Mayor of Surakarta, PDIP, Cons) 12.58%; M. Chatib Basri (Government, Minister of Finance, Pros) 6.73%; Hanung Budya (Government, Director of Marketing and Commerce PT Pertamina (Persero), Pros) 5.76%; and Ali Mundakir (Government, Vice President Corporate Communication Pertamina, Pros) 5.18%.

According to Table 5, of the 20 main discourses in the fuel increase discourse coalition in the Tempo.co mediatization, the supporting (Pros) discourse coalition consists of seven substantial discourses related to the fuel increase as follows: fuel conversion subsidy, BLT compensation certainty, energy conversion, reducing the state budget burden, right reason, alternative energy search, and right compensation. In addition, six non-substantive discourses are outside the issue of the fuel increase, or political discourse, namely authority of the government, DPR approval, government mandate, good communication from the government to the DPR, public support, and mature socialization.

Table 5.

Discourse ranking by degree of centrality in Tempo.co, 2013.

Table 5 also presents data on closeness centrality, a measure that describes how close a discourse is to other discourses, where closeness refers to how easy or difficult it is for a discourse to be reached by other discourses in the network within the coalition (Eriyanto, 2022: 168, referring to McCulloh et al., 2013). The five discourses with the highest proximity centrality are government authority, (Pros), 6.52%; fuel conversion subsidy, (Pros), 5.91%; BLT compensation certainty, (Pros), 5.25%; energy conversion, (Pros), 4.97%; reducing the budget burden, (Pros), DPR approval, (Pros), and good communication from government to DPR, (Pros), all 4.61%. Here, it can be observed that Pro discourses dominate the population of discourses with proximity centrality, so counter-discourses are relatively marginalized in contesting the two coalitions.

4.2.2. Dominant Cons Discourse in Tempo.co in 2022

Processing the data from Tempo.co using DNA with the aim of determining the 20 most vigorous discourses (or concepts) in terms of degree of centrality revealed the five most dominant discourses were reducing the burden on the state budget (Pros) and government authority (Pros), 4.97%; ineffective fuel conversion subsidy (Cons), certainty of protection for poor people (Pros), and fuel conversion subsidy (Pros) 4.70%. From these findings, Tempo.co’s discourse on the 2022 fuel hike was dominated by a larger coalition of discourses in favor (n = 12) than those against (n = 8).

Table 6 shows that 20 main discourses in the fuel increase discourse coalition on Tempo.co mediatization, the coalition of supporting (Pros) discourses is dominated by 12 discourses (60% of the top 20 most vigorous discourses according to the degree of centrality) with total control over the total discourse of 47.51%. The rejecting (Cons) discourse had a population of eight discourses (40% of the top 20 most vigorous discourses according to the degree of centrality) with total control over the total discourse of 24.03%, or a relatively significant difference. A total of seven out of twelve supporting (Pros) discourses consisted of substantial discourses related to the fuel increase, namely reducing the burden on the state budget, certainty of protection of poor people, fuel conversion subsidy, appropriate compensation, appropriate reason, fuel increase requirements fulfilled, alternative energy search, and certainty of BLT compensation. In addition, there are four non-substantive discourses outside the fuel increase issue, or political discourse, namely, government authority, government mandate, DPR approval, and good communication from the government to DPR.

Table 6.

Discourse based on the ranking of the degree of centrality in Tempo.co, 2022.

Table 6 presents data on betweenness centrality, a measure that describes an actor’s position as a link to other actors in the network between coalitions (Eriyanto, 2022; McCulloh et al., 2013). The five discourses with the highest betweenness centrality were ineffective fuel conversion subsidy (Cons) 21.23%; increase in goods prices (Cons) 12.48%; certainty of protection of poor people (Pros) 6.94%; reducing the burden on the state budget (Pros) 5.33%; and shock effect of fuel increase (Cons) 4.29%. Here, it can be observed that counter-discourses dominate the discourse population with proximity centrality, so Pros-discourses are relatively marginalized in contesting the two coalitions, just as in the proximity centrality condition.

4.3. Discourse Coalition Network in Kompas.com

4.3.1. The Actor and Discourse Coalition Network in Kompas.com

The analysis of the influence between actors and discourses using discourse network analysis (DNA) demonstrates that the status of discourse discussed by each individual actor significantly affects how opinion bias operates within society. Leifeld further argues that, although the resulting networks can be analyzed at the actor level, concept level, or combined mode level, perhaps the most interesting level from a policy network perspective is the actor level. An actor suitability network connects two policy actors if both use the same concept in the same way at least once, either positively or negatively. The more concepts two actors agree on, the greater the weight of the ties connecting them, normalized by the average number of concepts used by both actors overall. Such networks mirror the coordination relationships found in policy network studies: both types of networks are based on actors in the policy domain and can represent coalitions of actors as part of closely interconnected networks (Leifeld, 2020).

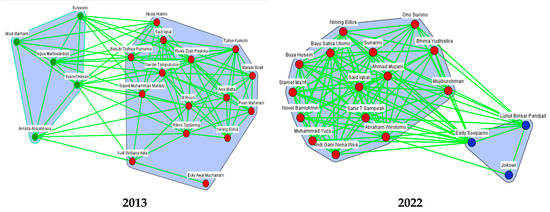

Figure 1 reveals that Syarief Hasan possesses a high degree of centrality, bolstered by substantial closeness and betweenness centrality. This indicates that the discourses delivered by Syarief Hasan (as a Pros actor) are interconnected with those delivered by other Pros actors (closeness centrality) and counter actors, such as Basuki Tjahaja Purnama and Yudi Widiana (betweenness centrality). Although the influence of counter-actors is numerically greater than that of Pros actors, the mediation influence on the extent of public opinion remains evident.

Figure 1.

Actor network for the 2013 and 2022 fuel price increase in Kompas.com.

Scheme 2024. The relationship between discourses and actors in 2013 depicted in Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of complex political and social interactions. Meanwhile, the public support discourse functions as a critical bridge (betweenness) between the Pros and Cons discourses, highlighting the essential role of public support in bridging conflicting views. Conversely, Cons discourses such as antipathy to fuel price increases and government arbitrary actions compete with pros discourses supporting the government and its policies, such as the right reason discourse, which attempts to justify the price increases. Figure 1, showcasing the principal actors in this discussion, provides additional context by illustrating how various actors contribute to the existing discourse, either reinforcing or opposing specific narratives, thus exerting significant influence in the debate. The integration of these two figures demonstrates how social and political actors interact to influence and shape public opinion, forming a complex network that connects diverse perspectives and interests.

Based on Figure 1 regarding the actor network on the 2022 fuel price increase issue, Eddy Soeparno emerged as the actor with the highest degree of centrality, indicating a central role in disseminating and connecting various discourses related to the fuel price increase. As a politician from the National Mandate Party (PAN), Eddy supports the Pros discourse articulated by Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, who holds the highest betweenness value among Pros actors. This signifies Luhut’s pivotal role in bridging and connecting various issues, thereby facilitating significant information flow within the network. President Jokowi, although exhibiting a moderate degree of centrality, possesses a high betweenness value, indicating that the issues he raises function as a crucial bridge for subsequent discourses expressed by other actors. This underscores Jokowi’s strategic role in agenda-setting and influencing the direction of public discourse. The combination of actors with varied roles reflects the political and social complexity surrounding the fuel price increase issue, where diverse interests and views interact and influence each other, forming a dynamic and multidimensional discussion network.

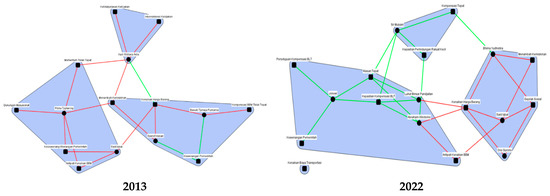

Based on the analysis of Figure 2 regarding actor--discourse affiliation on the 2013 fuel price hike issue, it is evident that Ribka Tjiptaning plays a central role as an actor with high degree of centrality, closeness, and betweenness values. This signifies that Ribka Tjiptaning wields considerable influence within the affiliation network, particularly by promoting dominant counter discourses. The counter discourses advanced by Ribka Tjiptaning include Inappropriate Momentum, Government Arbitrariness, Antipathy to Fuel Price Hike, and Increasing Poverty. These discourses reflect robust criticism of the fuel price hike policy, emphasizing disagreement with the timing of the policy’s implementation and its adverse impact on public welfare and poverty rates.

Figure 2.

Actor-discourse coalition network on the 2013 and 2022 fuel price increase in Kompas.com. Source: Results processed using Visone, 2024.

Conversely, actors such as Syarief Hasan, Yudi Widiana, and Basuki Tjahaja Purnama act as intermediaries within the Pros and Cons actor-discourse affiliation network, presenting discourses both in support of and against the policy. Their role as important liaisons facilitates dialogue and interaction between divergent views, maintaining the balance of discussion and creating space for diverse perspectives. Said Iqbal, another actor who articulated counter discourses, strengthened the opposition by presenting his two most dominant counter discourses. The involvement of these actors in the actor-discourse affiliation network illustrates how the 2013 fuel price hike issue has evolved into a field of conflict and political negotiation involving various actors with diverse interests and views. The high degree of centrality of Ribka Tjiptaning underscores a dominant role in directing public opinion, while the high closeness and betweenness of bridging actors such as Syarief Hasan, Yudi Widiana, and Basuki Tjahaja Purnama emphasize the importance of interaction and connectedness in shaping public discourse dynamics. This highlights the political and social complexity surrounding the fuel price hike issue, where various interests and views interact and influence each other.

Based on the data presented in Figure 2, which pertains to the actor-discourse affiliation network during the 2022 fuel price hike issue, Said Iqbal is identified as a central counteractor, exhibiting relatively high values in degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality. This suggests that Iqbal wields substantial influence within this network and plays a crucial role in articulating the prevailing counter-discourse. His counter-discourses encompass themes such as the Price Increase in Goods, Social Unrest, Increasing Poverty, and Opposition to Fuel Price Increases. These contributions highlight Iqbal’s active engagement in emphasizing the adverse effects of the fuel price hikes and reinforcing the opposition’s stance on the policy. In a secondary yet notable position, Bhima Yudhistira also contributes to the counter-discourse by addressing issues like the Price Increase in Goods, Social Unrest, and Increasing Poverty, thereby augmenting the counter-arguments. Additionally, there are actors such as Abraham Wirotomo and Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan who present both Pros and Cons discourses, indicating an effort to bridge the divide between opposing views and offer a more nuanced perspective on the fuel price hikes. On the Pros-policy side, President Jokowi assumes a strategic role by advocating a discourse aligned with those expressed by other Pros-policy figures, including Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Abraham Wirotomo, and Sri Mulyani. This alignment suggests that Jokowi aims to consolidate support for the policy and ensure coherence in the governmental messaging, supported by prominent figures within the administration.

This analysis underscores the intricate dynamics within the actor-discourse affiliation network. Counteractors, notably Said Iqbal and Bhima Yudhistira, significantly influence and disseminate discourse critical of the fuel price hikes. In contrast, actors such as President Jokowi, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, and Abraham Wirotomo seek to present a more balanced perspective or support the policy. This interaction illustrates the complex interplay of diverse interests and viewpoints within the public sphere, contributing to a multifaceted and robust debate on the issue of fuel price hikes.

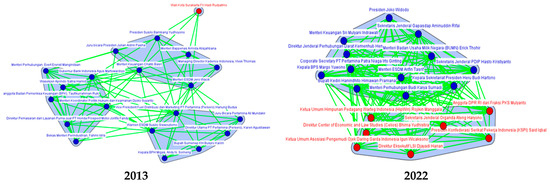

4.3.2. The Actor and Discourse Coalition Network in Tempo.co

Figure 3 shows three coalition groups of Pros-actors and only one Con-actor in Tempo.co media in 2013. The first coalition of Pros-actors consists of Government representatives such as President SBY, Julian Aldrin Pasha, Armida Alisjahbana, Chatib Basri, and Jero Wacik, and one businessman, Vivek Thomas. The second coalition of Pros-actors consists of actors in the oil and gas sector, such as Susilo Siswoutomo (Deputy Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources) and Andy N. Someng (Head of BPH Migas). Then, there are Karen Agustiawan, Ali Mundakir, and Hanung Budya, representing Pertamina, and KH Busyro Karim (Regent of Sumenep). The third coalition of Pros-actors consists of government representatives such as Djoko Suyanto (Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs), EE Mangindaan (Minister of Transportation), Agus Martowardoyo (Minister of Finance), and Taufiqurran Ruki (Member of BPK). Then there are civil society representatives, namely Satria Hamid (Wasekjen Aprindo) and Fami Idri (Former Minister of Transportation), as well as one businessman, Jonfis Fandy from Honda Prospect Motor. One counteractor is the Mayor of Surakarta, FX Hadi Rudyatmo.

Figure 3.

Actor network in the 2013 and 2022 fuel price increase in Tempo.co. Source: results processed using Visone, 2024.

Figure 3 also shows one coalition group of Pro and Con actors in Tempo.co media in 2022. Furthermore, each alliance connects the reconnected coalitions. This shows that the discourse related to the fuel price increase in Tempo.co in 2022 was not too polarized, because both Pro and Con actors drew on discourse from different coalitions.

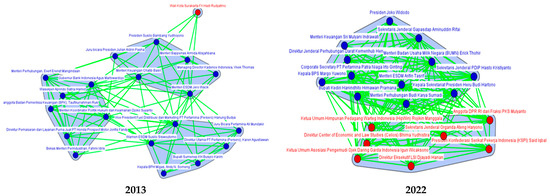

Figure 4 shows three coalition groups of Pro-actors and only one Con-actor in Tempo.co media in 2013. The first coalition of Pro-actors consists of Government representatives such as President SBY, Julian Aldrin Pasha, Armida Alisjahbana, Chatib Basri, and Jero Wacik, and one businessman, Vivek Thomas. The second coalition of Pro-actors consists of actors in the oil and gas sector, such as Susilo Siswoutomo (Deputy Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources) and Andy N. Someng (Head of BPH Migas). Then, there are Karen Agustiawan, Ali Mundakir, and Hanung Budya, representing Pertamina, and KH Busyro Karim (Regent of Sumenep). The third coalition of Pro-actors consists of Government representatives such as Djoko Suyanto (Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs), EE Mangindaan (Minister of Transportation), Agus Martowardoyo (Minister of Finance), and Taufiqurran Ruki (Member of BPK). There are also civil society representatives, namely Satria Hamid (Wasekjen Aprindo) and Fami Idri (Former Minister of Transportation), as well as one businessman, Jonfis Fandy from Honda Prospect Motor. One counteractor is the Mayor of Surakarta, FX Hadi Rudyatmo.

Figure 4.

Actor-discourse coalition network on the 2013 and 2022 fuel price increase in Tempo.co. Source: Results processed using Visone, 2024.

Figure 4 also shows that there is one coalition group of Pros and Cons actors in Tempo.co media in 2022. Furthermore, it can be seen that many actors in each coalition connect the relationship between coalitions. This shows that the discourse related to the increase in fuel prices in Tempo.co media in 2022 was not too polarized because both Pros and Cons actors used the discourse delivered by diferent coalitions of actors.

5. Discussion

This study’s central theoretical contribution is demonstrating how mediatization and media logic contribute to the fragmentation and politicization of public discourse on contentious policy issues, using the case of fuel price controversies in Indonesia. Drawing from mediatization theory, framing theory, and discourse network theory, we argue that the proliferation of digital platforms has reshaped the nature of policy debates. Rather than being confined to government-driven economic narratives, these debates have evolved into contested symbolic arenas where public grievances, moral claims, and populist framings dominate. We focus our analysis on one key insight: that mediatized political communication disperses discursive authority, allowing broader participation while intensifying fragmentation and competition over meaning. This argument is empirically substantiated through Discourse Network Analysis (DNA), which visualizes how actor-concept relationships evolve and how competing coalitions coalesce around specific narratives. Our findings show that in 2013, dominant actors primarily emphasized macroeconomic justifications for fuel subsidy reduction. In contrast, by 2022, the discourse had shifted toward socio-political concerns—rising living costs, inequality, and political distrust—voiced by a wider set of civil society actors and non-governmental figures.

This transformation is not merely an outcome of shifting political alignments but reflects more profound structural changes in how discourse operates within a hybrid, digitally networked media environment. Mediatization theory predicts that political communication becomes increasingly shaped by the logic of the media as follows: emotional resonance, dramatization, and personalization (Altheide, 2016; Hepp, 2020a). These dynamics were observable in the 2022 data, where counter-discourses gained traction through narratives emphasizing hardship and government unresponsiveness rather than fiscal rationality. The empirical findings clarify what media ‘do’ in this context: they strategically filter, frame, and amplify competing narratives based on institutional priorities, commercial considerations, and political affiliations. Rather than being passive channels, digital media platforms function as selective mediators that shape which actors gain visibility and which frames dominate at a given time. As Altheide (2016) and Hjarvard (2008) have argued, media logic privileges narratives that are emotionally resonant, visually appealing, and conflict-oriented. Our analysis shows that this logic structured the representation of fuel subsidy debates in ways that favored populist critiques in 2022, contrasting with the more technocratic and centralized framings of 2013.

These shifts are not simply the byproduct of generic “digital discourse” but reflect deeper contestations over political meaning, as emphasized in Schlogl’s (2022) analysis of digital activism in the context of global middle-class discontent. In his study of Indonesia’s fuel subsidy protests, Schlogl shows that middle-class actors mobilized digitally to construct moral claims of injustice, betrayal, and elite insensitivity, displacing the state’s economic rationale with populist frames of suffering and entitlement. This symbolic reframing, he argues, is key to understanding the politicization of subsidy discourse and the rising antagonism toward technocratic narratives.

Our findings echo and extend Schlogl’s insights by showing that such digitally mediated, middle-class discourses are not confined to social media platforms but are also incorporated—and often amplified—by mainstream news outlets like Tempo.co and Kompas.com. These platforms, though traditionally rooted in journalistic conventions, respond to shifting public sentiment and evolving attention economies by curating affectively resonant frames, elevating civil society voices, and featuring symbolic narratives (e.g., “fuel injustice” and “burden on the poor”) that echo the digital populism described by Schlogl.

For instance, in the 2022 discourse network, actors representing labor unions, NGOs, and consumer associations were more structurally central than in 2013, and their most frequently associated concepts emphasized injustice, affordability, and public hardship. Media outlets played a critical role in constructing this coalition by repeatedly featuring such voices and organizing headlines around grievances rather than economic logic. These editorial choices do not merely reflect public opinion—they shape it by rearticulating the dominant conflict in terms that resonate with mediatized publics.

In this sense, what media “do” is more than transmit discourse: they participate in discursive restructuring by selecting speakers, framing narratives, and amplifying certain conceptual linkages. Media logic is operationalized through affective framing, frame repetition, and actor amplification, all of which are visible in the evolving topology of discourse networks. These dynamics validate Schlogl’s argument that fuel pricing debates are not just economic but profoundly symbolic struggles over public legitimacy intensified through hybrid media ecologies.

Ultimately, the fragmentation and politicization of fuel subsidy discourse are systemic outcomes of deep mediatization. As digital networks expand, the discursive boundaries of public policy are no longer controlled solely by formal institutions but are shaped through dynamic interactions among actors, frames, and media logics. In this environment, legitimacy is negotiated through visibility and affect rather than deliberation or expertise. This insight has significant implications for governance in the digital age: while media afford broader participation, they challenge consensus-building and reduce the effectiveness of technocratic communication.

Discourse network analysis provided a structural visualization of these transformations, revealing how key actors and dominant concepts reconfigured across two distinct media ecosystems. In both Kompas.com and Tempo.co, the 2022 discourse reflected a greater diversity of voices and an increase in populist framings, indicating that public debate over fuel subsidies is no longer centered on technical policy justifications but is embedded in broader struggles over social justice and legitimacy. International comparisons further reinforce these findings. For example, Leifeld (2013) demonstrated how shifts in German pension policy discourse mirrored underlying structural realignments in advocacy networks. Similarly, Fergie et al. (2019) showed that discursive coalitions in Scottish alcohol policy evolved, reflecting the entrance of new frames and actors. Like these studies, our analysis reveals that fuel pricing debates in Indonesia did not remain static but became more contested, emotionally charged, and widely disseminated within a mediatized public sphere.

This study affirms that the media increasingly operate not as neutral conveyors of information but as political actors embedded in networks of meaning-making. Their content decisions reflect not only journalistic norms but also commercial and political considerations. The shift from Pros-dominated narratives in Tempo.co in 2013 to a more oppositional discourse by 2022 highlights how media platforms adapt to shifting power configurations and audience expectations. Such shifts are consistent with the concept of media logic, where the format and framing preferences of media organizations shape the boundaries of public discourse (Altheide, 2016).

Ultimately, while digital media environments may enable broader participation in public debate, they also generate challenges for deliberative policymaking. Fragmentation, polarization, and the amplification of populist narratives complicate consensus-building and reduce the effectiveness of technocratic communication. As our findings demonstrate, even with increased public engagement, discourse on fuel policy frequently fails to translate into tangible policy shifts. Instead, discourse coalitions compete within a fragmented media space, where legitimacy is constantly renegotiated but rarely consolidated. Future research may extend this framework by examining additional policy controversies in Indonesia or conducting cross-national comparisons of discourse networks on subsidy reforms. Researchers may also integrate social media platforms more explicitly to understand how hybrid media systems—combining mass and participatory media—shape discourse coalitions and policy outcomes in the digital age.

The patterns observed in our study align with broader findings on fuel price policy debates. Analysts have noted that without effective public engagement, fuel subsidy cuts often meet strong resistance; for example, Chelminski (2018) emphasizes that political leadership and strategic communication campaigns are crucial for public acceptance of subsidy reforms. Consistent with our observation of intense opposition narratives, a recent cross-country study conducted by the IMF found that fuel price increases tend to spur social unrest and anti-government protests if not carefully managed (Drabo et al., 2023). These insights underline the fact the fragmented, contentious discourse we found in 2013 and 2022 is not unique—it reflects a common challenge in fuel price reforms, where governments must better inform and involve the public to mitigate backlash.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Indonesia’s digital media environment has transformed how fuel price controversies are framed and contested. Through discourse network analysis, we find that public debates have evolved from centralized, government-led justifications in 2013 to more fragmented and populist narratives in 2022. Kompas.com and Tempo.co, though differing in editorial direction, both reflect a broader shift away from technocratic rationales toward discourses emphasizing public grievance, social inequality, and distrust of elite decision-making. This shift is driven by the deepening of mediatization and the increasing influence of networked public discourse.

By applying a network-theoretical framework to analyze discourse structures, we show how coalitions of meaning form, evolve, and compete within a hybrid media system. These findings reveal that legitimacy in public policy is not only about evidence and authority but also about how effectively narratives are constructed, circulated, and aligned with public sentiment. Despite heightened engagement, these discursive dynamics have yet to translate into coherent or deliberative policy responses. The discourse on fuel subsidies remains highly contested, symbolically potent, and shaped by a decentralized media logic that prioritizes visibility and affects over resolution.

Future studies should further investigate the implications of this mediatized fragmentation for democratic governance. Expanding the analysis to include social media platforms and alternative media could shed light on how hybrid discourse ecosystems contribute to polarization or create new avenues for inclusive participation in policy debates. This study also engages with and builds upon insights from recent research such as Schlogl (2022), affirming that the reframing of fuel policy in socio-political terms is part of a broader communicative and societal transformation. Future studies should investigate how these dynamics unfold across different policy domains and media systems. Integrating social media platforms and activist discourse more explicitly may offer a fuller picture of how digital contestation influences legitimacy and policy outcomes in transitional democracies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P. and B.I.; methodology, N.P. software, N.P.; validation, N.P., B.I. and A.N.A.; formal analysis, N.P.; investigation, N.P.; resources, N.P.; data curation, N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.P.; writing—review and editing, B.I. and A.N.A.; visualization, N.P.; supervision, B.I. and A.N.A.; project administration, N.P.; funding acquisition, N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research does not involve human participants and has met the standards and approval of research ethics from the Head of Doctoral Study Program Department of Communication Gadjah Mada University Indonesia, who approved this study on 21 November 2024 (Ref. No. 627/PSP-KOM/S3/SEKR/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informant consent was waived because this research did not involve human participants and solely analyzed news texts from Kompas.com and Tempo.co.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable for this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | Accessed dates for websites Kompas.com and Tempo.co: 20 July 2024. |

References

- Abzianidze, N. (2020). Us vs. them as structural equivalence: Analysing nationalist discourse networks in the Georgian print media. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheide, D. L. (2016). Media logic. In G. Mazzoleni (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of political communication (1st ed., pp. 1–6). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antlöv, H., & Wetterberg, A. (2021). Indonesia: Deliberate and deliver–deepening Indonesian democracy through social accountability. In Deliberative democracy in Asia (pp. 38–53). Routledge. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003102441-3/indonesia-hans-antl%C3%B6v-anna-wetterberg (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Bartels, K. P. R., Wagenaar, H., & Li, Y. (2020). Introduction: Towards deliberative policy analysis 2.0. Policy Studies, 41(4), 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J., & Warren, M. (2018). Deliberative democracy: An introduction. In A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, & M. Warren (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. L., & Pfetsch, B. (2018). Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C. (2020). Gatekeeping the plenary floor: Discourse network analysis as a novel approach to party control. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. University of California Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=HVuognZFofoC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Blumer,+Herbert.+(1969).+Symbolic+interactionism:+Perspective+and+methods,+New+Jersey:+Prentice+Hall.&ots=4pQgL8wX9u&sig=H-YEl3kR1AYoE10X9dyohiMDiwQ (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Bossner, F., & Nagel, M. (2020). Discourse networks and dual screening: Analyzing roles, content and motivations in political twitter conversations. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the internet age. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chelminski, K. (2018). Fossil fuel subsidy reform in Indonesia: The struggle for successful reform. In J. Skovgaard, & H. van Asselt (Eds.), The politics of fossil fuel subsidies and their reform (pp. 193–211). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, O., & Ocelík, P. (2020). Incumbents’ strategies in media coverage: A case of the Czech coal policy. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K. (2016). Symbolic interactionism. In The international encyclopedia of communication theory and philosophy (pp. 1–12). JohnWiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabo, A., Eklou, K. M., Imam, P. A., & Kpodar, K. (2023). 2023 IMF working papers social unrests and fuel prices: The role of macroeconomic, social and institutional Factors. IMF Working Papers, 2023(228). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwiyanto, A. (2004). Reorientasi ilmu administrasi publik: Dari government ke governance [Online post]. Gadjah Mada University. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, T. R. (1986). Community power and public policy. In R. J. Waste (Ed.), Community power: Directions for future research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, F. (2023). Discourse network analysis. In P. A. Mello, & F. Ostermann (Eds.), Routledge handbook of foreign policy analysis methods (pp. 516–535). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, J. (Ed.). (2002). Deliberative democracy (transferred to digital printing). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eriyanto, E. (2022). Analisis jejaring wacana discourse network analysis/DNA. Rosda Karya. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, F., & Strömbäck, J. (Eds.). (2014). Mediatization of politics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergie, G., Leifeld, P., Hawkins, B., & Hilton, S. (2019). Mapping discourse coalitions in the minimum unit pricing for alcohol debate: A discourse network analysis of UK newspaper coverage. Addiction, 114(4), 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. (2003). Reframing public policy: Discursive politics and deliberative practices. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F., & Gottweis, H. (2012). Introduction: The argumentative turn revisited. In F. Fischer, & H. Gottweis (Eds.), The argumentative turn revisited (pp. 1–27). Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M., & Leifeld, P. (2015). Policy forums: Why do they exist and what are they used for? Springer Society of Policy Sciences, 48(3), 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghinoi, S., & Steiner, B. (2020). The political debate on climate change in Italy: A discourse network analysis. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M. A. (1997). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M. A., & Wagenaar, H. (Eds.). (2003). Deliberative policy analysis: Understanding governance in the network society. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haunss, S., Kuhn, J., Padó, S., Blessing, A., Blokker, N., Dayanik, E., & Lapesa, G. (2020). Integrating manual and automatic annotation for the creation of discourse network data sets. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, A. (2020a). Deep mediatization. Routledge. [Google Scholar]