1. Introduction

Political communication is a multifaceted field encompassing the transmission of information, its influence on public sentiment, and its capacity to catalyze societal transformation. Early research on this rapidly developing phenomenon has focused on elections and voter behavior. Subsequent studies have broadened the scope to encompass diverse political engagements and sentiments. In the 21st century, the relationship between the media and politics has undergone a dramatic transformation. The rise of influential figures and a diversified media landscape have prompted a re-evaluation of traditional models of political influence. While earlier hypotheses have underscored the overwhelming impact of mass media, contemporary frameworks emphasize a more nuanced two-step communication process, wherein opinion leaders serve as intermediaries between mass media channels and the public (

Graber & Smith, 2005).

The digital media revolution has presented significant challenges and opportunities for political communications, introducing complexities that require new analytical frameworks to capture the intricate pathways through which information is disseminated on various social media platforms. To fully appreciate the transformative impact of digital technologies, it is essential to consider the technological advancements and evolving theoretical paradigms that have accompanied these changes. The intersection of technology and political communication is characterized not by linear progress but by recurring cycles of enthusiasm and skepticism. This cyclical dynamic necessitates a comprehensive framework for mapping the evolution of political communication strategies over time.

Political communication is central to this study and is understood as the exchange of information, messages, and meaning between political actors and the public through various media channels (

Jacobs & Shapiro, 1996;

Marques & Miola, 2021). In this context, the hype cycle, as conceptualized by Gartner company and elaborated by

Fenn and Raskino (

2008) illustrated through its distinct phases, is a valuable analytical tool for examining emerging technologies’ maturity, adoption, and social application.

Despite extensive research on the influence of digital media in political contexts, there remains a gap in the literature concerning the trajectory of digital political communication as understood through the lens of the technology hype cycle. While previous studies have examined various related aspects such as social media’s role in elections and the spread of misinformation (

Chester & Montgomery, 2017;

Toor, 2020), they have not analyzed how the stages of the hype cycle apply specifically to political contexts. This study addresses this gap by mapping political communication innovations onto the hype cycle framework, providing a comprehensive understanding of how digital tools and platforms have shaped political engagement and discourse from the mid-1990s to the present. The analysis encompasses key digital milestones, from early internet forums and email to Web 2.0 and contemporary social media platforms.

In recent years, the shift towards digital platforms has further underscored the importance of understanding the dynamic relationship between political communication and the evolving digital media landscape (

Alenzi & Miskon, 2024;

Hanson et al., 2010). Despite the rapid evolution of digital technologies since the 1990s, it is possible to discern four distinct phases that reflect the mutual dependence and interconnectedness between political communication practices and digital innovation. This study reviews the existing literature on political communication and the hype cycle model, establishes a theoretical framework to map the evolution of digital political communication, and provides insight into its future trajectory.

To guide this inquiry, this study focuses on three research questions: (1) Is the technology hype cycle model applicable to the evolution of political communication in the digital age? (2) What specific phases of the hype cycle have been observed in political communication strategies since the mid-1990s? (3) How have emerging technologies such as AI influenced the current political communication hype cycle?

This study employs a four-dimensional analytical framework to examine these questions: technological development (the emergence and potential of digital tools), platforms (digital environments and their affordances), practices (ways political actors engage with technologies), and academic discourse (shifts in scholarly perspectives). Each phase of the hype cycle is considered through four broad dimensions, which offer insights into the relationship among technological innovations, platform dynamics, political behaviors, and evolving academic interpretations within digital political communication.

2. The Hype Cycle Model

This study employs Gartner’s hype cycle, as described by

Fenn and Raskino (

2008), as its primary theoretical framework because the model captures technological adoption’s dynamic and cyclical nature, which is characterized by fluctuating expectations and subsequent realization. Indeed, stage-based analytical approaches of this kind are increasingly recognized for their utility in mapping the evolution of expectations, discourses, and innovations in complex socio-political domains, including political communication and policy processes (

Berry, 2023;

Kriechbaum et al., 2021;

Taschner et al., 2021). Therefore, this study undertakes a conceptual analysis by applying the hype cycle model as an interpretive framework to trace the evolution of political communication in the digital era (the mid-1990s to the present).

The hype cycle model complements foundational theories in political communication. Building on the classic two-step flow model originally detailed by

Katz (

1957), and enriched by subsequent studies on selective exposure (

Stroud, 2011;

Prior, 2007) and deliberative engagement (

Mutz, 2006), the framework introduces a temporal dimension that elucidates how media effects evolve over time. Unlike linear adoption models, the hype cycle model accounts for periodic peaks of inflated expectations, followed by troughs of disillusionment, culminating in a plateau in productivity. This cyclical pattern is particularly relevant to political communication, in which integrating digital tools often mirrors fluctuations in enthusiasm and skepticism. The model complements established political communication theories, such as the two-step flow model (

Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955), by introducing a temporal dimension that highlights the evolving influence of opinion leaders and mass media channels. By mapping political communication innovations onto the hype cycle, this study bridges the gap between technology adoption theories and political discourse dynamics, offering a nuanced understanding of how political strategies drive digital advancement.

Although the hype cycle has garnered significant attention from practitioners and scholars, its empirical validation remains limited (

Dedehayir & Steinert, 2016). For example,

Alkemade and Suurs (

2012) employed content analysis to reveal that stakeholders such as industry representatives, media, and policymakers perceive the same technology with varying degrees of optimism and skepticism, suggesting that diverse interests and motivations shape hype. In contrast,

Van Lente et al. (

2013) proposed a set of variables to delineate the phases of hype cycles, emphasizing external factors such as media and policy shifts and offering a more detailed understanding of how hype evolves. These empirical inconsistencies highlight the need to recognize the inherent exaggeration in current technology lifecycle models and evaluate the consequences of such exaggeration for innovation, media, and social systems such as the political arena.

The hype cycle provides a valuable framework for analyzing technological changes in political communication; however, its application beyond its original business context requires scrutiny. First, unlike commercial technologies, political communication operates within the power structures and cultural contexts that shape technology adoption in ways that the original model does not fully capture. Second, while the hype cycle assumes consistent temporal patterns, political communication follows variable timelines. Electoral cycles, media events, and crises can accelerate or delay progression through the stages of the model, thus challenging its temporal assumptions. For example, Twitter’s political adoption occurred rapidly, compressing the initial stages into months (

Kreiss, 2016), whereas blockchain integration proceeded more slowly. Third, the model presumes homogeneous adoption patterns, yet political communication varies widely across systems, cultures, and institutions. As

Chadwick (

2017) noted, “hybrid media systems” produce distinct patterns of innovation and use. We address this by highlighting both broader trends and contextual differences. Fourth, political communication technologies often evolve through feedback loops, although the hype cycle depicts linear progression. Regulatory actions, public backlash, and electoral outcomes generate dynamics that can lead to simultaneous advances and setbacks. For instance,

Kreiss and McGregor (

2018) showed that while data-driven campaigning advanced strategically, it lost legitimacy following privacy controversies.

Despite these limitations, the hype cycle remains valuable when carefully adapted. Its key strength is capturing the recurring cycles of enthusiasm and skepticism shaping the relationship between political communication and technology. Empirical studies have demonstrated the model’s explanatory value.

Alkemade and Suurs (

2012) mapped stakeholder optimism and skepticism, whereas

Van Lente et al. (

2013) identified variables to delineate hype cycle phases. These findings support the utility of the model in analyzing how expectations influence technology adoption. Our approach builds on these validations, while acknowledging the limitations of the model. To address these challenges, we adapted the five-stage hype cycle to a four-stage model better suited to political communication. We combined the “slope of enlightenment” and “plateau of productivity” into a single “measured understanding” phase, reflecting that political technologies rarely achieve stability but instead undergo continual reassessment. We also consider the perspectives of multiple stakeholders, allowing for a more nuanced analysis of technology adoption in political communication. An important aspect of this framework is its recognition that certain phenomena may appear across multiple phases of the hype cycle, although with varying characteristics and implications. For instance, echo chambers emerge during the disillusionment phase as unintended consequences of early platform design. Nevertheless, they resurfaced in later phases as strategically exploited through algorithmic targeting. Thus, the framework emphasizes the dominant characteristics of each phase while acknowledging that technological features and their effects can overlap, evolve, and recur with distinct implications as the cycle progresses.

In this analysis, our application of the adapted hype cycle model involved drawing from an extensive review of the scholarly literature on technological and political shifts to identify key innovations and their associated discursive patterns within the field. These developments and their corresponding phases of collective expectation (e.g., optimism, skepticism, and practical integration) were then mapped onto the stages of the adapted hype cycle.

The hype cycle identifies a technology’s evolution from its inception, marked by the excitement of the (1) technology trigger with no practical products, leading to (2) a peak of inflated expectations characterized by excessive enthusiasm. This is followed by (3) a trough of disillusionment, during which limitations become apparent, and then (4) a slope of enlightenment, during which pragmatic assessments of capabilities emerge. Finally, because technology is widely adopted, (5) productivity plateaus are accompanied by inherent risks and opportunities.

Applied to digital political communication, this framework reveals that early optimism regarding the Internet’s democratic potential eventually gave way to disillusionment as its limitations became evident. The subsequent rise in social media sparked renewed enthusiasm, albeit tempered by a growing awareness of potential misuse. By mapping the evolution of political communication onto a hype cycle, this study elucidates the recurring cycles of hype, disillusionment, enlightenment, and the integration of new technologies, contextualizing the oscillations between utopian visions and pragmatic realism.

Understanding the hype cycle in political communication is crucial for analyzing the impact of emerging technologies on political campaigns. Each cycle stage uniquely influences political actors’ adoption and utilization of digital tools. For instance, during the peak of inflated expectations, campaigns may overestimate the impact of a new social media platform without fully accounting for its limitations. At the same time, in the trough of disillusionment, there may be a retreat from such platforms in response to challenges such as misinformation or user privacy concerns. Mapping political communication developments onto the hype cycle thus facilitates better prediction of adoption patterns and strategic adjustments in response to technological innovations.

3. A Short History of Media Enthusiasm

Media research boasts a rich history, with early scholars employing metaphors such as the “magic bullet” and the “hypodermic needle” to illustrate media’s potent societal effects in the early 20th century (e.g.,

Lippmann, 1922;

Lasswell, 1927;

Cantril, 1940). Such models, based on the assumption that humans were biologically hardwired to respond instinctively to media messages, were not grounded in empirical research and have since been disproven by more sophisticated models of communication that recognize the active role of audience members in interpreting and responding to media content (

Bryant & Zillmann, 2009;

Valkenburg et al., 2015). Subsequent theories, including

Katz’s (

1957) two-step flow model, underscored the critical role of opinion leaders in mediating media messages, a concept further elaborated in the 1960s and 1970s by researchers who expanded its scope (

Weimann, 2017).

K. B. Jensen (

2010) further advanced this discussion by proposing a three-stage flow of communication that acknowledged the complexity and diversity of information distribution. These evolving theoretical paradigms reflect technological development and shifts in academic discourse about media influence, establishing patterns that would recur as digital platforms emerge.

With the advent of the World Wide Web in the 1990s, academic literature began documenting the evolution of online communication platforms in distinct stages. In today’s digital era, political leaders harness the Internet to extend their influence, a shift that has polarized scholarly discourse into cyber-optimistic and -pessimistic camps (

Kabanov & Romanov, 2017). This bifurcation, however, masks a more profound transformation—the digital turn that has blurred the boundaries between public and private spheres and redefined state–society relations (

Fuchs & Chandler, 2019). Consequently, a refined understanding of the societal influence of technology and its future implications is essential.

The advent of the Internet, initially developed for military purposes before shifting to academic and later public applications (

Frohmann, 1994), marked a pivotal milestone. American political actors soon recognized its potential, sparking a transformation in political engagement (

Foot & Schneider, 2002;

Margolis & Resnick, 2000). In the early days of the Internet—often described as an “age of innocence”—scholars and practitioners alike were optimistic, viewing the medium as a solution to democratic challenges that could empower citizens and strengthen the public–representative relationship (

Brants, 2005).

Wellman (

2004) characterized it as an era of hope, where innovations such as asynchronous email, discussion lists, and instant messaging transcended the conventional limitations of time and space.

Early democratic optimism also posed theoretical challenges for establishing communication models. In particular, scholars have speculated that the Internet’s direct connectivity might enable a quasi-one-step flow of information between political elites and citizens, effectively bypassing the intermediary role of opinion leaders that is central to the classic two-step flow model (

Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955;

O’Regan, 2021). The prospect of such disintermediation suggests that information could reach individuals unfiltered by traditional mass media gatekeepers, flattening hierarchical influence structures (

O’Regan, 2021). These expectations implicitly raised questions about whether Katz’s mid-century insights into opinion leadership would still hold in an era of online forums and email chains. However, in retrospect, hopes of completely bypassing mediators proved overly optimistic: digital communities quickly cultivated new influencers and opinion leaders within their networks, rather than eliminating mediated influence (

Harff et al., 2025).

Nevertheless, as

Wellman (

2004) noted, this optimism overlooked the entrenched power imbalances within political, economic, and cultural structures.

Habermas (

1989) argued that such power disparities often rendered democratic aspirations vulnerable to self-interest. The digital age intensified these dynamics, shifting the balance of power further toward authoritative content creators and away from dispersed citizen-driven narratives (

Iosifidis, 2011;

Kaul, 2012).

As public trust in traditional media waned, exacerbated by the revelations of ethical breaches, hidden affiliations, and power misuse by major media conglomerates (

Blumler & Gurevitch, 2001;

Dahlgren, 2005), the digital sphere emerged as a viable alternative for the free flow of information. Despite this potential, political strategies during the late 1990s remained anchored in conventional approaches such as billboards, print materials, and broadcast media, with early websites offering only rudimentary candidate information (

Margolis & Resnick, 2000). The new millennium, however, heralded a critical turning point, as digital media were more fully integrated into political processes, giving rise to innovative strategies and platforms.

This historical progression lays the groundwork for applying the hype cycle to political communications. Each technological milestone, from radio and television to the Internet and social media, has generated a cycle of hype and subsequent reassessment. Recognizing these recurring patterns is crucial for analyzing current and future disruptions, such as those caused by AI. Having established the initial optimism associated with early internet use in political communication, it is imperative to examine how these hopeful beginnings gradually yielded disillusionment as the inherent limitations of digital platforms emerged.

5. The Rise of Social Media

From the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s, Web 2.0 is widely recognized as the third stage in the evolution of political communication. This period profoundly influenced political discourse’s psychological, social, cultural, and economic dimensions (

Dutton, 2009;

Spaeth, 2009). Campaign strategies increasingly harnessed digital tools—a process well documented by

Kreiss (

2012)—to mobilize voters and redefine political outreach. At the same time, debates on mediated authenticity (

Enli, 2015) challenged traditional narratives, while analyses of digital protest dynamics during events such as the Arab Spring (

Howard & Hussain, 2013) underscored social media’s dual capacity to empower grassroots mobilization and generate contentious debates.

As

Chadwick (

2007) noted, the rise of online social networks during this phase revived the early optimism associated with the Internet. This view was shared by

Loader and Mercea (

2011), who highlighted platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Wikis, and the broader blogosphere as sources of renewed technological hope.

This surge in enthusiasm relied on a vision of increased citizen participation in lifestyle and identity politics, self-organized networking, and everyday users as democratic innovators. Web 2.0 transformed citizens into a more engaged and informed electorate by enabling global opinion sharing, connection building, and real-time discussion.

Dutton (

2009) even conceptualized social media users as the “fifth estate”—a digital community network capable of reinforcing and accelerating political mobilization that he described as occurring in “internet time”—and ultimately enhancing political openness and accountability.

The transformative impact of social media is perhaps best exemplified by their role during the Arab Spring uprisings of 2010–2011. Platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have proved instrumental in organizing protests and disseminating critical information, effectively bypassing state-controlled media channels (

Tufekci & Wilson, 2012). These tools not only facilitated collective action and amplified marginalized voices but also underscored the double-edged nature of social media by presenting governments with opportunities to monitor and control dissent (

Howard & Hussain, 2013). For instance, during the 2011 protests against President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, activists utilized Facebook pages—such as “We Are All Khaled Said”—to organize demonstrations and raise awareness of issues such as police brutality and state corruption. Conversely, the Egyptian government exploited the same platforms for surveillance, even instituting a nationwide internet shutdown to disrupt protest coordination. This strategy ultimately backfired by drawing international media attention and prompting activists to seek alternative communication channels (

Khamis et al., 2012).

The complex interplay between online citizens and the governing authorities has prompted calls for a more nuanced understanding of these dynamics.

Couldry (

2012) argued that superficial analyses of these interactions failed to capture the evolving phases of digital political engagement. A more refined approach acknowledged that this evolution encompassed emerging network-based political frameworks, gradual transformations among political elites, innovative political processes, and recurring cycles of democratization.

In contemporary political communication, platforms such as Facebook, X, and YouTube have become indispensable (

Steinfeld & Lev-on, 2024). The widespread use of smartphones, with their integrated cameras and instant sharing capabilities, has further accelerated the dissemination of visual content, thereby reshaping media narratives, political discourse, and public debate (

Spaeth, 2009;

Penney, 2017). However, this digital environment presents challenges for politicians, who must now navigate the delicate balance between controlling the flow of information and maintaining a clear demarcation between their individual and professional personas.

The capacity of social media to advance political agendas is vividly illustrated by the 2008 US presidential election, where Barack Obama’s strategic use of these platforms mobilized and engaged potential voters in unprecedented ways (

Spaeth, 2009). By leveraging the civic enthusiasm of their supporters, political campaigns boosted voter engagement and redefined the traditional modes of political outreach (

Chadwick & Stromer-Galley, 2016). This strategic integration demonstrates how technological capabilities, platform affordances, refined political practices, and renewed academic optimism could converge to create genuinely transformative political communication.

In conclusion, the advent of Web 2.0 marked a significant advancement in political communication, reshaping the democratic arena by creating direct channels between politicians and their constituents. This paradigm shift can be further understood through the lens of participatory communication theory, which underscores users’ active role in producing and disseminating content, aligning with the slope of enlightenment phase of the hype cycle. Crucially, the rise of participatory platforms in this era reconfigured influence dynamics in political communication. Information flows have become more decentralized and networked as ordinary citizens, and emerging digital influencers have assumed roles as content creators and disseminators alongside traditional media elites (

Harff et al., 2025). This evolution exemplifies the tenets of participatory communication theory, articulated initially by

Freire (

1970) and later applied to media contexts by

Carpentier (

2011), which emphasizes dialogic, bottom-up engagement and the blurring of lines between audiences and producers. Moreover, empirical research confirms that social media’s participatory affordances have, on average, enhanced civic engagement and that the correlation between online networking and political participation has grown substantially stronger in the Web 2.0 era (

Boulianne, 2020). Today, social networks not only facilitate real-time communication and enable data-driven campaign strategies (

Stromer-Galley, 2014), but also introduce new complexities, including challenges related to data privacy and the proliferation of misinformation.

7. Artificial Intelligence and Political Communication

Artificial intelligence (AI) represents new technology triggers in the hype cycle, introducing both innovative opportunities and significant challenges for political communication. One of their most critical applications is personalized messaging, where algorithms analyze extensive voter data to generate highly targeted political messages. This data-driven approach enables campaigns to tailor communication to specific demographics, interests, and concerns, enhancing engagement and persuasive effectiveness.

Political campaigns increasingly leverage AI-based chatbots and virtual assistants on websites and messaging platforms. These tools engage voters by answering questions and providing candidates and policy information around the clock, thus enhancing accessibility and responsiveness (

Kim & Lee, 2023;

Tosi et al., 2025). Similarly, sentiment analysis powered by algorithms examines social media posts, comments, and other digital content, allowing campaigns to gauge public opinion in real time and rapidly adjust their strategies. Additionally, AI algorithms facilitate real-time sentiment analysis on social media, allowing political parties to monitor shifts in public opinion and swiftly adjust messaging strategies to address emerging concerns (

Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, 2013).

Predictive analytics constitutes another frontier in which AI is making significant strides. AI systems can accurately forecast voting behavior and election outcomes by dissecting historical data, demographic trends, and current events. Such insights are invaluable for optimizing campaign strategies and resource allocation (

Bach et al., 2021;

Gupta et al., 2024). Moreover, AI-driven content generation facilitates the production of campaign materials, ranging from social media posts and email newsletters to speech drafts, ensuring consistent and streamlined messaging across platforms. These applications demonstrate how AI simultaneously advances technological capabilities, creates new platform functionalities, enables sophisticated political practices, and generates fresh academic debates on democratic engagement.

The transformative role of AI in political campaigns is exemplified by its use in the 2016 US presidential election, where sophisticated algorithms analyzed vast amounts of voter data to create tailored messaging that resonated deeply with the targeted demographics (

Howard & Kollanyi, 2016). Similarly, during the 2017 French presidential election, AI-powered chatbots enabled Jean-Luc Mélenchon to interact directly with voters on social media platforms, enhancing his campaign’s interactivity and accessibility (

Ferrara, 2017).

Collectively, these AI applications underscore the potential of data-driven strategies to enhance voter engagement and adapt political messaging to dynamic preferences, thus offering a more responsive approach to modern political campaigns. However, the challenges posed by the integration of AI, such as the proliferation of deepfakes, illustrate a familiar dynamic of the hype cycle model. The initial surge of optimism and rapid adoption (peak of inflated expectations) has been tempered by the growing recognition of severe risks to information integrity and democratic trust (trough of disillusionment). This pattern is especially apparent, as the dangers of deepfakes, including their potential for manipulation and disinformation (

Chesney & Citron, 2019), have led to heightened calls for regulatory intervention and transparency (

Pasquale, 2015). These responses reflect a collective movement toward the slope of enlightenment, where stakeholders seek to balance innovation with accountability.

The debate over AI regulation in political communication is integral to this cyclical progression. While well-designed AI tools can foster a more inclusive discourse and help groups find common ground, their adoption raises significant concerns regarding transparency and accountability (

Tessler et al., 2024). The transparent use of AI-generated content may build trust, but poorly designed or undisclosed systems risk eroding public confidence (

Kreps & Jakesch, 2023). Moreover, as

Jungherr and Schroeder (

2023) caution, AI may reinforce existing power structures and marginalize dissenting voices, underscoring the need for ongoing critical engagement. Recognizing these dynamics can help policymakers and researchers anticipate future developments and design effective interventions for emerging technological shifts. Beyond AI, emerging technologies such as blockchain and augmented reality, which are still rarely utilized within the political communication context, could offer additional prospects for the future framework of the hype.

8. Conclusions

This study maps the evolution of digital political communication through the lens of Gartner’s hype cycle, detailed in

Fenn and Raskino (

2008), highlighting recurring cycles of optimism and skepticism. More than a historical overview, this application provides a distinct analytical lens for understanding the predictable, yet often disruptive, patterns of technological integration specific to the political sphere. The analysis in this study segments each phase of the hype cycle into four dimensions—technological development, platforms, practices, and academic discourse—thereby identifying the challenges posed by the modern information environment. These include the pervasive dissemination of misinformation and the potential for media manipulation.

From early enthusiasm for the Internet’s democratic promise to today’s integration of AI, each phase reflects a dynamic interplay between technological innovation and evolving political strategies. These findings underscore the need for a nuanced understanding of these hype-driven phases and the continuous adaptation and rigorous evaluation of emerging technologies to safeguard democratic principles. By understanding these cyclical dynamics, particularly how different stages of the hype cycle create specific democratic vulnerabilities or opportunities, political actors and policymakers can better navigate the digital landscape, ensuring that technological adoption reinforces rather than undermines democratic ideals.

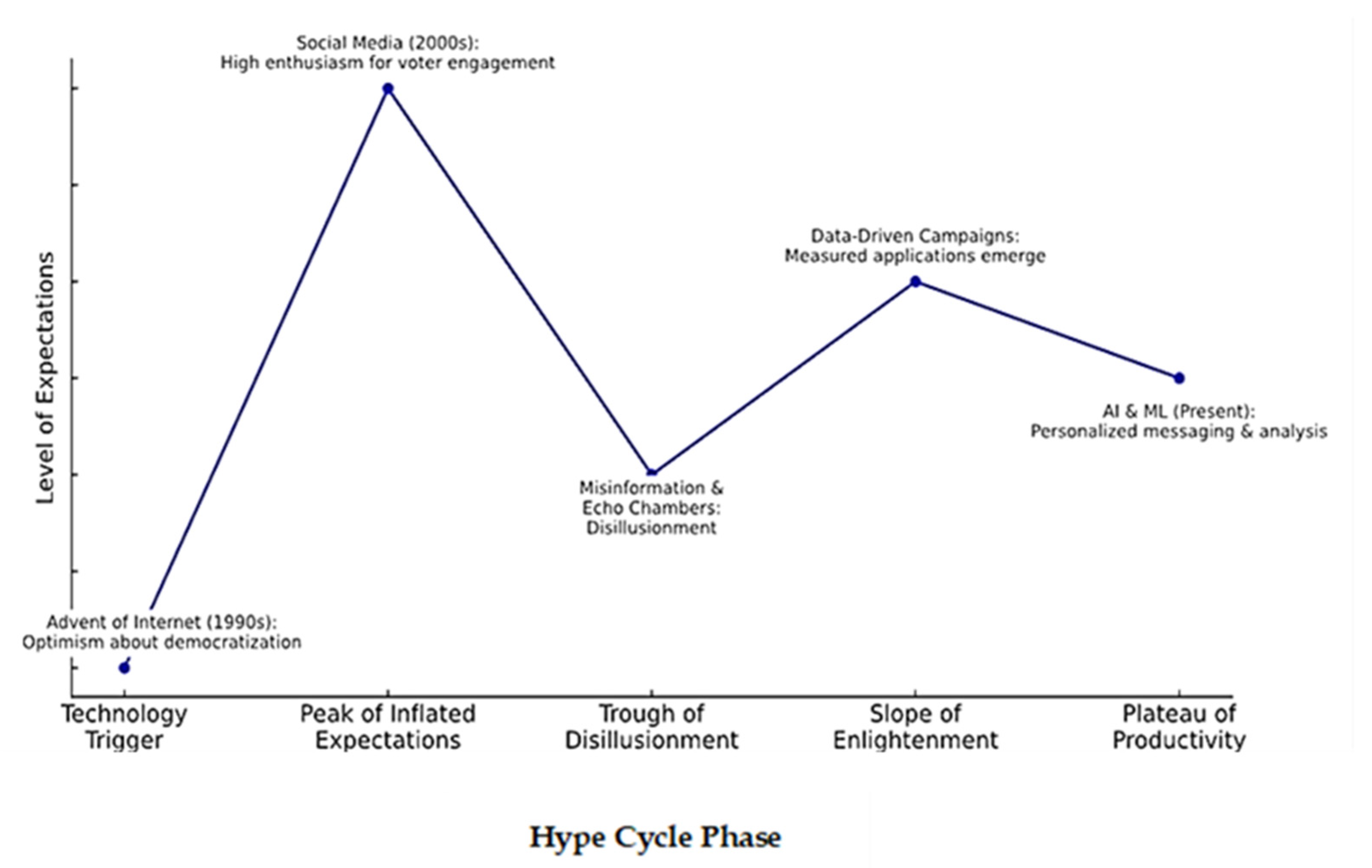

As illustrated in

Figure 1, integrating digital tools into political communication follows a trajectory consistent with the Gartner hype cycle (

Fenn & Raskino, 2008). Its stages capture the oscillation between enthusiasm and realism and provide critical insights into the ongoing evolution of digital platforms in political communication.

Figure 1 highlights the key milestones, challenges, and innovations characterizing each hype cycle stage. For example, during political campaigns, the

peak of inflated expectations captures the optimism surrounding the transformative potential of social media platforms such as X and Facebook. In contrast, the

trough of disillusionment reflects the critical realities that have emerged, including the rampant spread of misinformation, the formation of echo chambers, and increasing polarization, all of which have tempered earlier enthusiasm. The framework also helps explain the adaptation of the hype cycle model for political communication, such as the proposed “measured understanding” phase, which reflects that political technologies seldom achieve a stable “plateau of productivity” due to the constantly contested nature of the political arena.

This exploration, tracing digital technologies in political communication from the mid-1990s to the present, reveals a recurring cyclical pattern, rather than a simple linear trajectory of innovation and adoption. As demonstrated, the initial optimism surrounding the Internet’s democratic promise (the “technology trigger” and early “peak of inflated expectations”), the subsequent “trough of disillusionment” with the rise of misinformation and echo chambers, the renewed enthusiasm driven by social media (a subsequent “peak”), and the current phase of measured, data-driven applications—including the emergence of AI and its nascent hype cycle—all align with the stages described by

Fenn and Raskino’s (

2008) elaboration of Gartner’s model..

Figure 1 shows how each technological epoch—characterized by innovations, strategic adoption by political actors, and societal responses—maps onto these stages. The visual representation highlights the milestones and challenges discussed and the broader cyclical dynamics of inflated expectations, disillusionment, and eventual integration, which are fundamental to understanding the technology–political practice relationship.

The stages depicted in

Figure 1 capture the oscillation between enthusiasm and realism, providing critical insights into the ongoing evolution of digital platforms in political communication. This figure highlights the key milestones, challenges, and innovations that characterize each hype cycle stage. For example, during political campaigns, the peak of inflated expectations captures the optimism surrounding the transformative potential of social media platforms, such as X and Facebook. In contrast, the trough of disillusionment reflects the critical realities that have emerged, including the rampant spread of misinformation, the formation of echo chambers, and increasing polarization, all of which have tempered earlier enthusiasm. The positioning of “misinformation and echo chambers” at the lowest point of the “level of expectations” axis within this trough visually underscores their pivotal role in drastically reducing initial high expectations. Furthermore, the framework as applied also helps explain the adaptation of the hype cycle model for political communication, such as the “measured understanding” phase illustrated, which reflects that political technologies seldom achieve a stable “plateau of productivity” due to the constantly contested nature of the political arena.

In synthesizing the evolution of political communication through the hype cycle framework, this study underscores recurring challenges, such as over-optimism, misuse of technology, and emerging ethical dilemmas. These findings highlight the importance of adopting a critical, measurable, and ethical approach to integrating new technologies into political campaigns, informed by an awareness of the misaligned expectations among stakeholders that can drive both innovation and contestation. Although innovations such as AI offer unprecedented opportunities for engagement and efficiency, they also introduce significant risks that align with the hype cycle’s progression from inflated expectations to a trough of disillusionment if not managed proactively. A nuanced understanding of their applications and implications is required to ensure that digital tools reinforce democratic principles rather than undermine them.

Beyond underscoring the urgent need to improve general media literacy and foster critical thinking skills, this study’s application of the hype cycle points to the need to develop a broader systemic and strategic literacy regarding these cyclical technological adoption patterns. Such literacy would enable political actors, media organizations, and citizens to better anticipate and navigate the pressures of hype and disillusionment.

While earlier eras of digital innovation were heralded as potential reinforcers of democracy, they also raised concerns about their use as tools for manipulation.

Bennett and Iyengar (

2008) argued that the current media landscape promotes selective exposure and diminishes political persuasion. Although

Holbert et al. (

2010) critique this view as overstating media influence, rapid changes have expanded opportunities for selective exposure, as contended by

Shehata and Strömbäck (

2013). This study confirms that despite the prevalence of selective exposure, traditional media play a dominant role in shaping public discourse.

Building on these insights, it is evident that the digital revolution has amplified longstanding concerns and introduced new dynamics into political communication. Digital technology has fundamentally transformed political communication by equipping politicians with a digital toolbox capable of disseminating both accurate and misleading information (

Stromer-Galley, 2014;

Velasco Molpeceres et al., 2025). Classical media influence theories, such as the hypodermic needle model, have traditionally been dismissed because of the mediating role of traditional media gatekeepers and opinion leaders in the flow of information between political elites and the public (

Weimann, 2017). Digital platforms increasingly allow political actors to bypass traditional journalistic filters, facilitating direct communication with segmented audiences through algorithmic personalization and microtargeting (

Prummer, 2020). Emerging evidence indicates that even when users are aware of being microtargeted, the persuasive effectiveness of tailored political messaging remains substantial (

Carrella et al., 2025). As direct communication strategies increasingly bypass mainstream media gatekeepers, the need for rigorous scrutiny of information sources becomes increasingly critical (see, for example,

Elishar-Malka et al., 2020).