How Party-System Dynamics Shape Political Parties’ Use of Facebook Between Elections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review

3. Theory and Hypothesis

3.1. Party-System Dynamics

3.2. Party-Type Differences

4. Methodology

4.1. Selection of Denmark as a Case

4.2. Choice of Data Collection Period

4.3. Coding of Data

5. Results

5.1. Content Type Most Used

5.2. Type of Political Party

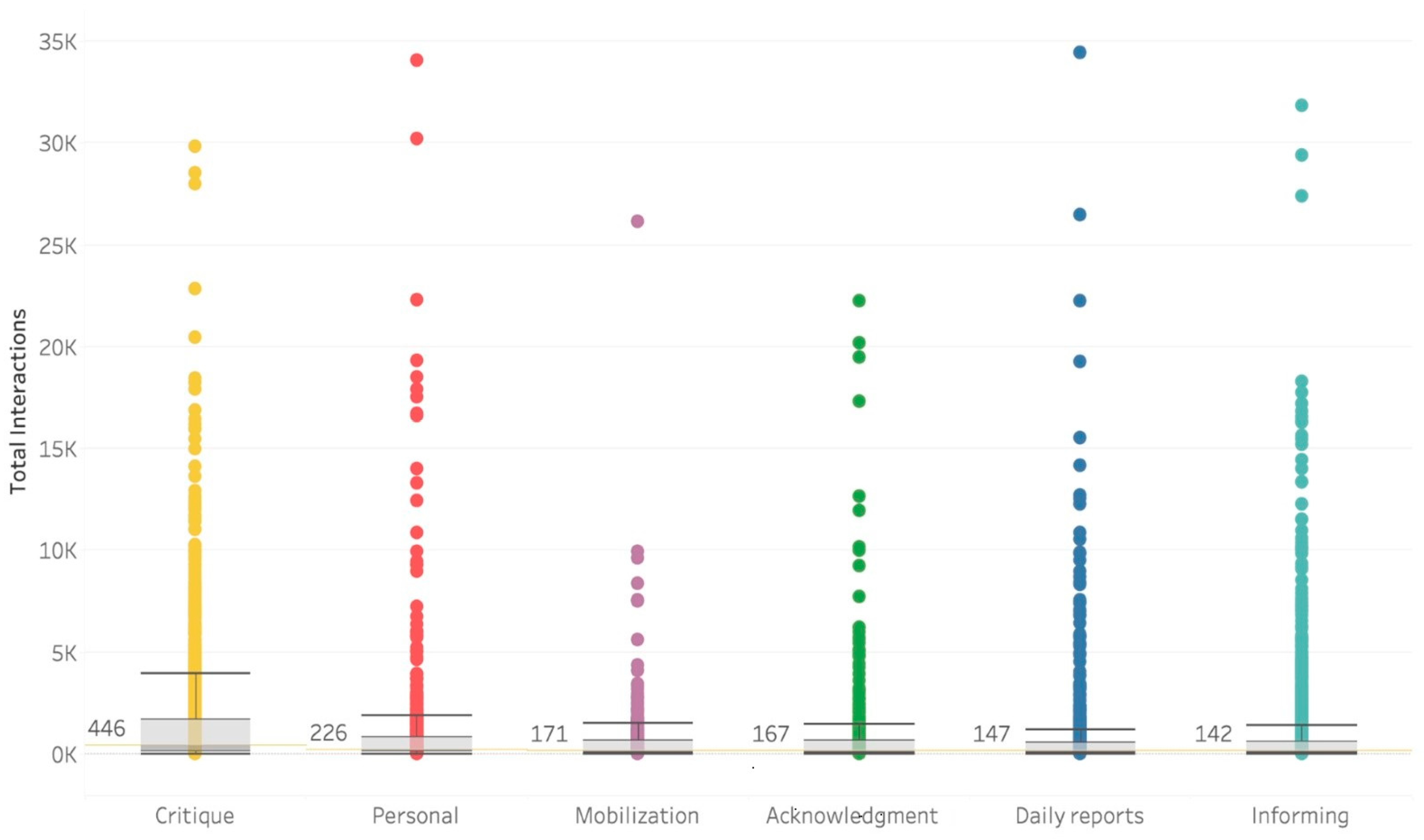

5.3. Who Gets the Most Attention?

6. Discussion

6.1. The Immigration-Argument as Driver

6.2. Mediatization as Driver

6.3. Newsworthiness as Driver

6.4. Does Election Campaigning Have an Effect?

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | ||

| Constant | 952.440 (357.805) ** | |

| Category | ||

| Daily reports | −204.961 (111.099) | |

| Personal | 226.451 (163.414) | |

| Information | Reference | |

| Mobilization | −73.757 (141.878) | |

| Acknowledgments | 31.868 (65.452) | |

| Critique | 333.008 (83.975) ** | |

| Party | Danish People’s Party | −292.118 (203.308) |

| Red–Green Alliance | −125.044 (150.623) | |

| Conservatives | 392.196 (385.749) | |

| Venstre | Reference | |

| Independents | −436.260 (1154.889) | |

| Danish Social Liberal Party | −180.552 (214.226) | |

| Liberal Alliance | −97.704 (200.396) | |

| New Right | 2702.882 (1088.796) ** | |

| Social Democrats | −17.321 (121.393) | |

| Socialist People’s Party | −110.970 (141.496) | |

| Alternative | 150.829 (100.996) | |

| Sex | Female | 47.751 (185.697) |

| Male | Reference | |

| Followers | 0.038 (0.004) ** | |

| Age | −21.913 (6.435) ** | |

| N | 5092 | |

| R2 | 0.531 | |

| Figures given in parentheses are standard errors. Significance level: **: p < 0.01 | ||

References

- Agresti, A., & Finlay, B. (2014). Statistical methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J. G., Christiansen, P., Frandsen, A., & Hansen, R. (2019). PolitikNU: Holdninger, magt og politiske systemer. Systime. [Google Scholar]

- Angenendt, M., & Brause, S. D. (2024). The long way towards polarized pluralism: Party and party system change in Germany. In T. Poguntke, & W. Hofmesister (Eds.), Political parties and the crisis of democracy: Organization, resilience, and reform (pp. 82–107). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, M., Bürgisser, R., & Häusermann, S. (2021). Attitudinal polarization towards the redistributive role of the state in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(S1), 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafumi, J., & Shapiro, R. Y. (2009). A new partisan voter. Journal of Politics, 71(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Fallin Hunzaker, M. B., Lee, J., Mann, M., Merhout, F., & Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(37), 9216–9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, M. (2017). Sharing is caring! Investigating viral posts on politicians’ Facebook pages during the 2014 general election campaign in Hungary. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(4), 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Bilewicz Michałand Soral, W. (2020). Hate speech epidemic. The dynamic effects of derogatory language on intergroup relations and political radicalization. Political Psychology, 41(S1), 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, J. (2018). Explaining the emergence of political fragmentation on social media: The role of ideology and extremism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(1), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, F. J. (2022). The liberal party: From agrarian and liberal to centre-right catch-all. In P. Munk Christiansen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Danish politics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Darius, P., & Stephany, F. (2019). “Hashjacking” the debate: Polarisation strategies of Germany’s political far-right on twitter. In I. Weber, K. M. Darwish, C. Wagner, E. Zagheni, L. Nelson, S. Aref, & F. Flöck (Eds.), Social informatics (Vol. 11864, pp. 298–308). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. A. J. (2002). Party system change, voter preference distributions. Party Politics, 8(2), 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjam, M., & Loxbo, K. (2023). Social conformity or attitude persistence? The bandwagon effect and the spiral of silence in a polarized context. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 34(3), 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galais, C., & Cardenal, A. S. (2017). When David and Goliath campaign online: The effects of digital media use during electoral campaigns on vote for small parties. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(4), 327–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garimella, K., De Francisci Morales, G., Gionis, A., & Mathioudakis, M. (2018, April 23–27). Political discourse on social media: Echo chambers, gatekeepers, and the price of bipartisanship. The Web Conference 2018—Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, WWW 2018 (Vol. 2, pp. 913–922), Lyon, France. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. K., & Mcallister, I. (2015). Normalising or equalising party competition? Assessing the impact of the web on election campaigning. Political Studies, 63(3), 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2020). The party system: Open yet stable. In P. Munk Christiansen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Danish politics (pp. 213–229). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halberg Nielsen, L., & Bang Pedersen, M. (2023). Ideology and system trust as drivers of COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors across eight Western countries. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K. M., & Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2017). How campaigns polarize the electorate: Political polarization as an effect of the minimal effect theory within a multi-party system. Party Politics, 23(3), 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, R., Schmuck, D., & Matthes, J. (2019). What drives interaction in political actors’ Facebook posts? Profile and content predictors of user engagement and political actors’ reactions. Information Communication and Society, 22(10), 1497–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C. P., Suphan, A., & Meckel, M. (2016). The impact of use motives on politicians’ social media adoption. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(3), 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopmann, D. N., Elmelund-Præstekær, C., Albæk, E., Vliegenthart, R., & de Vreese, C. H. (2012). Party media agenda-setting: How parties influence election news coverage. Party Politics, 18(2), 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J. L., & Schwartz, S. A. (2020). The 2019 Danish general election campaign: The ‘Normalisation’ of social media channels? Scandinavian Political Studies, 43(2), 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. F., Leahy, R., Restrepo, N. J., Velasquez, N., Zheng, M., Manrique, P., Devkota, P., & Wuchty, S. (2019). Hidden resilience and adaptive dynamics of the global online hate ecology. Nature, 573(7773), 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T. R., & Königslöw, K. K. (2018). Pseudo-discursive, mobilizing, emotional, and entertaining: Identifying four successful communication styles of political actors on social media during the 2015 Swiss national elections. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 15(4), 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchheimer, O. (1966). The transformation of Western European party systems. In J. LaPalombara, & M. Weiner (Eds.), Political parties and political development (pp. 177–200). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger, U., & Russmann, U. (2017). “Beer is more efficient than social media”—Political parties and strategic communication in Austrian and Swiss national elections. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(4), 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc-Michalska, K., Lilleker, D. G., Michaelski, T., Gibson, R., & Zajac, J. M. (2021). Facebook affordances and citizen engagement during elections: European political parties and their benefit from online strategies? Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 18(2), 180–193. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kulager, F. (2020, December 10). Jeg faldt over en guldmine af data om dansk politik. Nu ved jeg nøjagtig, hvor svært oppositionen har det. Zetland. Available online: https://www.zetland.dk/historie/s8YxwyJG-aOZj67pz-ff1b4 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Larsson, A. O. (2015). Pandering, protesting, engaging: Norwegian party leaders on Facebook during the 2013 ‘Short campaign’. Information Communication and Society, 18(4), 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. O. (2019). Skiing all the way to the polls: Exploring the popularity of personalized posts on political Instagram accounts. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 25(5–6), 1096–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-On, A., & Haleva-Amir, S. (2018). Normalizing or equalizing? Characterizing Facebook campaigning. New Media and Society, 20(2), 720–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleker, D. G., Koc-michalska, K., Negrine, R., & Gibson, R. (2017). Social media campaigning in Europe: Mapping the terrain. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(4), 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynggaard, E. H. (2021). Nye borgerlige stormer frem og har nu tredje flest medlemmer. TV2.Dk. Available online: https://nyheder.tv2.dk/politik/2021-02-17-nye-borgerlige-stormer-frem-og-har-nu-tredje-flest-medlemmer (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Magin, M., Larsson, A. O., Skogerbø, E., & Tønnesen, H. (2024). What makes the difference? Social media platforms and party characteristics as contextual factors for political parties’ use of populist political communication. Nordicom Review, 45(s1), 36–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetts, H. (2006). Cyber parties. In R. S. Katz, & W. Crotty (Eds.), Handbook of party politics (pp. 528–535). Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariager, R., & Olesen, N. W. (2022). The social democratic party. From exponent of societal change to pragmatic conservatism. In P. Munk Christiansen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Danish politics (pp. 278–295). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, G., & Schulz, W. (1999). “Mediatization” of politics: A challenge for democracy? Political Communication, 16, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, M., Kruikemeier, S., & Lecheler, S. (2020). Personalization of politics on Facebook: Examining the content and effects of professional, emotional, and private self-personalization. Information Communication and Society, 23(10), 1481–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T. M., & Miller, B. (2015). The niche party concept and its measurement. Party Politics, 21(2), 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, C. D. (2021). No effect of partisan framing on opinions about the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(S1), 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Arguedas, A. R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Reuters institute digital news report 2024. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, T. (2020). Media and politics: The Danish media system in transformation. In P. Munk Christiansen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Danish politics (pp. 417–432). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, R. T., Anspach, N. M., Hansen, K. M., & Arceneaux, K. (2021). Political predispositions, not popularity: People’s propensity to interact with political context on Facebook. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 34(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, J., Opgenhaffen, M., Kreutz, T., & Van Aelst, P. (2023). Understanding the online relationship between politicians and citizens. A study on the user engagement of politicians’ Facebook posts in election and routine periods. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 20(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M. B., Osmundsen, M., & Arceneaux, K. (2018). The “Need for Chaos” and motivations to share hostile political rumors. PsyArXiv, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel-Azran, T., Yarchi, M., & Wolfsfeld, G. (2015). Equalization versus normalization: Facebook and the 2013 Israeli elections. Social Media and Society, 1(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, G. (2005). Party types, organisation, and functions. West European Politics, 28(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, G. (2016). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. In S. Collier, & A. Lakoff (Eds.), Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis (pp. 154–163). Rowman & Littlefield International. [Google Scholar]

- Schmuck, D., & Hameleers, M. (2020). Closer to the people: A comparative content analysis of populist communication on social networking sites in pre- and post-Election periods. Information Communication and Society, 23(10), 1531–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. A. (2020). Medialisering og partiledernes kommunikation på Facebook i løbet af FV19. In I. T. Guldbrandsen, & S. N. Just (Eds.), #FV19: Politisk kommunikation på digitale medier (p. 89). Samfundslitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Seeberg, H. B. (2020). Issue ownership attack: How a political party can counteract a rival’s issue ownership. West European Politics, 43(4), 772–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeberg, H. B., & Kölln, A. (2022). The red-green alliance introducing the red-green alliance: Is it red or green? In P. Munk Christiansen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Danish politics (pp. 329–346). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaci, M. Z. (2018). Inter-party competition on Facebook in a non-election period in Turkey: Equalization or normalization? Journal of Southeast European and Black Sea, 18(4), 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, J. (2008). Four phases of mediatization: An analysis of the mediatization of politics. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilling, D., Tolochko, P., & Burscher, B. (2017). From newsworthiness to shareworthiness: How to predict news sharing based on article characteristics. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(1), 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urman, A. (2020). Context matters: Political polarization on Twitter from a comparative perspective. Media, Culture and Society, 42(6), 857–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dalen, A., Fazekas, Z., Klemmensen, R., & Hansen, K. M. (2015). Policy considerations on Facebook: Agendas, coherence, and communication patterns in the 2011 Danish parliamentary elections. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(3), 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. (2012). Defining and measuring niche parties. Party Politics, 18(6), 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J. K. (2006). Definition of party. In R. S. Katz, & W. Crotty (Eds.), Handbook of party politics (pp. 5–15). Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, A. (2019). Online hate: From the far-right to the ‘alt-right’ and from the margins to the mainstream. In Online othering (pp. 39–63). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinetz, S. B. (2006). Party systems and party system types. In Handbook of party politics (pp. 51–62). Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollebæk, D., Brekke, J. P., & Fladmoe, A. (2022). Polarization in a consensual multi-party democracy–attitudes toward immigration in Norway. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 34(2), 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Post | Definition | Examples of Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Daily reports | Posts documenting the work of politicians (e.g., participation in negotiations, visits outside the Folketing, participation in live debates). Daily reports provide followers with regular updates on the political or professional activities of the user. Through such updates, audiences gain insight into ongoing developments, fostering a sense of transparency and immediacy. This form of communication leverages the “always-on” nature of social media, allowing for real-time engagement that keeps supporters connected to the politician. We use this category instead of the “campaign reports” category in comparable research that focuses on campaign activities on behalf of the more mundane online activities of politicians (see Larsson, 2015; Jensen & Schwartz, 2020). | Examples of posts are tasks and milestones in or from daily political activities, as well as updates on individual politicians’ careers. One politician describes what her tasks for the day involve. Another politician shares that he has taken on a new role in a committee. |

| Personal | Posts where politicians share personal details from their private lives, outside their daily reports (e.g., hobbies, family, or other general things or activities that communicate the politician’s personal life). Personal posts offer glimpses into the private lives of Members of Parliament. | Examples of posts are sharing a visit to the hairdresser or sharing celebrating a wedding anniversary. |

| Information | Posts that communicate political views and positions are often centered around new legislation or political initiatives. These posts typically aim to inform the audience with fact-oriented content, providing clarity and context about complex topics. They are designed to educate and engage, ensuring followers understand key issues and the rationale behind specific actions or proposals. By presenting accurate and reliable information, such posts reinforce credibility and authority in the subject matter. | Examples are posts about a stance on mosques in Denmark or posts about a political agreement that has been reached. |

| Mobilization | Posts where the politician attempts to motivate and engage receivers and followers to participate online by liking, commenting, or sharing the post or offline by participating in events or voting in elections. | Examples of posts are a politician’s attempt to encourage Facebook users to sign a voter declaration or a post where a politician seeks input on where new bike paths are needed. |

| Acknowledgment | Posts where the politician acknowledges new initiatives or actors (e.g., political opponents, the media, or citizen groups) with positive sentiment. These posts focus on expressing gratitude and recognition, whether directed at supporters, colleagues, or specific groups. These posts often reinforce positive relationships and foster a sense of appreciation within the community. By thanking individuals or groups, public figures can build goodwill and strengthen bonds with their audiences. | Examples of posts are praising a political fellow for his contributions to Danish politics. Another example is an acknowledgment of an entire group of people, like the armed forces. |

| Critique | Posts where the politician criticizes political initiatives, current affairs, political opponents, the media, or groups of citizens with negative sentiment. | Examples of posts where a politician criticizes a political opponent for portraying a scare narrative about the left-wing bloc, a politician calling the defense minister the worst ever encountered, or a post criticizing the government’s climate policies. |

| Party Name | Political Orientation | Party Type |

|---|---|---|

| Social Democratic Party (SDP) | Left | Catch-all/relevant |

| Danish Social-Liberal Party (SLP) | Center-left | Catch-all/relevant |

| Venstre—the Liberal Party of Denmark (V) | Right | Catch-all/relevant |

| The Conservative People’s Party (CPP) | Right | Catch-all/relevant |

| Socialist People’s Party (SPP) | Left | Catch-all/relevant (populistic) |

| Red–Green Alliance (RGA) | Left | Catch-all (niche voter segment) |

| Danish People’s Party (DPP) | Right | Catch-all (populistic) |

| New Right (NR) | Right | Niche/irrelevant |

| Liberal Alliance (LA) | Right | Niche/irrelevant |

| Alternative (A) | Center-left | Niche/irrelevant |

| Party | MP | Posts | Posts * | Interactions | Interactions * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 43 | 43 | 12,746 | 296.4 |

| RGA | 13 | 481 | 37 | 323,000 | 671.5 |

| SPP | 15 | 369 | 24.6 | 330,024 | 894.4 |

| SPD | 49 | 1036 | 21.1 | 1,167,499 | 1126.90 |

| SLP | 14 | 365 | 26.1 | 245,792 | 673.4 |

| V | 39 | 1136 | 29.1 | 401,794 | 353.7 |

| CPP | 13 | 479 | 36.8 | 478,466 | 998.9 |

| DPP | 16 | 653 | 40.8 | 698,797 | 1070.10 |

| LA | 3 | 151 | 50.3 | 177,769 | 1177.30 |

| NR | 4 | 229 | 57.3 | 1,356,267 | 5922.60 |

| Independent | 8 | 151 | 18.9 | 295,715 | 1958.40 |

| Information | Critique | Daily Reports | Acknowledge | Personal | Mobilization | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPP | 30.2(197) | 38.6(252) | 12.4(81) | 3.5(23) | 9.2(60) | 6.1(40) | 100% |

| RG | 43(207) | 29.1(140) | 7.3(35) | 7.9(38) | 2.3(11) | 10.4(50) | 100% |

| CD | 37.6(180) | 34.7(166) | 10.4(50) | 6.3(30) | 6.1(29) | 5(24) | 100% |

| LA | 28.5(43) | 58.9(89) | 6.6(10) | 2.6(4) | 2.7(4) | 0.7(1) | 100% |

| Ind. | 39.7(60) | 25.8(39) | 9.2(14) | 0(0) | 8.6(13) | 16.6(25) | 100% |

| NR | 24.9(57) | 54.2(124) | 8.7(20) | 4.8(11) | 6.1(14) | 1.3(3) | 100% |

| SLP | 38.6(141) | 17.3(63) | 19.5(71) | 9.6(35) | 6(22) | 9(33) | 100% |

| S | 40.8(423) | 4.7(49) | 19.6(203) | 15.4(159) | 14.7(152) | 4.8(50) | 100% |

| SPP | 54.5(201) | 18.7(69) | 10.6(39) | 7(26) | 4.9(18) | 4.3(16) | 100% |

| V | 40.4(459) | 23(263) | 13.5(153) | 8.5(97) | 9.1(103) | 5.4(61) | 100% |

| A | 32.6(14) | 32.6(14) | 11.6(5) | 14(6) | 0(0) | 9.3(4) | 100% |

| Total | 38.9% | 24.9% | 13.5% | 8.4% | 8.3% | 6% | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aagaard, P.; Schwartz, S.A.; Nygaard, L.; Larsen, M.T. How Party-System Dynamics Shape Political Parties’ Use of Facebook Between Elections. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010006

Aagaard P, Schwartz SA, Nygaard L, Larsen MT. How Party-System Dynamics Shape Political Parties’ Use of Facebook Between Elections. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleAagaard, Peter, Sander Andreas Schwartz, Line Nygaard, and Malene Teresa Larsen. 2025. "How Party-System Dynamics Shape Political Parties’ Use of Facebook Between Elections" Journalism and Media 6, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010006

APA StyleAagaard, P., Schwartz, S. A., Nygaard, L., & Larsen, M. T. (2025). How Party-System Dynamics Shape Political Parties’ Use of Facebook Between Elections. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010006