Digital Political Communication in the European Parliament: A Comparative Analysis of Threads and X During the 2024 Elections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework: The Digital Turn in Political Communication

2.1. The Platformization of Politics: A New Electoral Landscape

2.2. Digital Democracy and the Transformation of Political Institutions

- (1)

- Real-time citizen engagement: European institutions have expanded their digital presence through live Q&A sessions, interactive policy forums, and real-time debates. Platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook Live, and YouTube have become essential tools for legislators to engage directly with the public (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2024).

- (2)

- Transparency and digital governance: The European Parliament provides real-time updates on legislative proceedings, policy decisions, and voting outcomes through online platforms. This initiative aims to bridge the democratic deficit by fostering greater institutional accountability (Shahreza, 2024).

- (3)

- Counter-disinformation initiatives: To address the proliferation of fake news and manipulated political narratives, the EU has partnered with fact-checking agencies, AI-driven verification tools, and independent media watchdogs (Zinnbauer, 2021). These measures seek to ensure that electoral processes remain free from digital manipulation.

- (1)

- Amplification of Eurosceptic and nationalist rhetoric: state-sponsored media outlets and troll farms have strategically promoted anti-EU sentiment, portraying Brussels as an authoritarian bureaucracy that undermines national sovereignty.

- (2)

- Deepfake propaganda and AI-generated misinformation: advances in artificial intelligence have enabled the creation of hyper-realistic deepfake videos, falsely depicting EU officials and candidates engaging in fabricated scandals or making misleading policy statements.

- (3)

- Exploitation of algorithmic biases: foreign actors have leveraged social media platforms’ engagement-driven algorithms to spread viral misinformation, ensuring that misleading content reaches millions before fact-checking mechanisms can intervene (R. Liu et al., 2022).

- (1)

- Election infrastructure attacks: reports indicate that cyberattacks targeting electoral commission databases, campaign email servers, and government digital platforms have increased in frequency, raising concerns over potential data breaches (Bleyer-Simon et al., 2024).

- (2)

- Bot-driven political manipulation: automated bot networks have been used to flood social media discussions with fabricated narratives, artificially amplifying divisive political debates while suppressing legitimate discourse (García-Orosa, 2021).

- (3)

- Algorithmic content distortion: malicious actors manipulate search engine algorithms and trending topics to ensure that misleading political content dominates online political discussions in critical election periods (Tucker et al., 2018).

- (1)

- The Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA): these legislative frameworks impose stricter obligations on digital platforms regarding content moderation, political advertising transparency, and data protection (Kettemann & Schulz, 2023).

- (2)

- Fact-checking partnerships: European institutions have established collaborations with independent media organizations and fact-checking agencies to mitigate the spread of digital misinformation (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2024).

- (3)

- Election security task forces: coordinated efforts between EU cybersecurity agencies and member-state intelligence services aim to strengthen digital infrastructure resilience and prevent foreign electoral interference (Gerbaudo, 2024).

2.3. Misinformation and Algorithmic Manipulation in Elections

- (1)

- Emotional Amplification and Political Polarization: Studies indicate that anger, outrage, and fear-based narratives perform better than fact-based, policy-driven discussions (Borz & De Francesco, 2024). This phenomenon fosters ideological polarization, making bipartisan consensus-building increasingly difficult (Campos-Domínguez et al., 2022).

- (2)

- Filter Bubbles and Echo Chambers: Algorithmic personalization leads to self-reinforcing ideological echo chambers, where users are repeatedly exposed to content that aligns with their preexisting beliefs, reducing exposure to diverse perspectives (Bene et al., 2025). This has significant implications for voter behavior, as users become less likely to engage with countervailing viewpoints (Törnberg & Törnberg, 2024).

- (3)

- The Rise of Algorithmic Populism: Populist rhetoric thrives in high-engagement digital environments, disproportionately amplifying anti-establishment messaging while sidelining institutional perspectives (McNair, 2023). This has led to an increase in populist electoral successes, as algorithm-driven amplification provides a direct pathway to mass mobilization without reliance on traditional media channels (Taneja, 2024).

- (1)

- Automated disinformation networks: Political campaigns and foreign actors have increasingly relied on bot networks to manipulate electoral discourse. These AI-driven systems can flood digital platforms with coordinated narratives designed to influence voter sentiment (Bleyer-Simon et al., 2024).

- (2)

- Deepfake political content: The 2024 European elections and Donald Trump’s U.S. presidential campaign saw an increase in the use of AI-generated political deepfakes. These sophisticated disinformation tactics erode public trust and make it increasingly difficult to differentiate between genuine political messaging and synthetic media.

- (3)

- Platform resistance to regulation: Despite increased scrutiny, major digital platforms have resisted comprehensive regulatory oversight, citing concerns over free speech and innovation (Kettemann & Schulz, 2023). The European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) represents a step toward platform accountability, yet enforcement mechanisms remain limited in scope (Gerbaudo, 2024).

- (1)

- Regulating AI-driven misinformation and political deepfakes: governments must strengthen regulatory oversight to combat emerging threats such as AI-generated disinformation and synthetic political content.

- (2)

- Ensuring electoral transparency through stronger governance mechanisms: the enforcement of digital political advertising disclosures, content moderation policies, and data privacy protections is essential for maintaining democratic accountability.

- (3)

- Empowering digital literacy initiatives to combat algorithmic polarization: public education on media literacy and critical thinking is necessary to counteract the effects of algorithmic bias and misinformation.

3. Objectives and Research Questions

- (O1)

- To analyze the posts made on the European Parliament’s Threads and X accounts during the 2024 European Parliament election campaign.

- (O2)

- To identify the differences in content publication between the European Parliament’s Threads and X accounts in their English versions.

- (O3)

- To quantify the engagement of followers on both social media platforms.

- (RQ1)

- What type of posts does the European Parliament publish on the Threads and X social media platforms?

- (RQ2)

- Are there any differences in the content posted on the European Parliament’s Threads and X accounts?

- (RQ3)

- What is the engagement level of followers on the European Parliament’s Threads and X accounts?

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

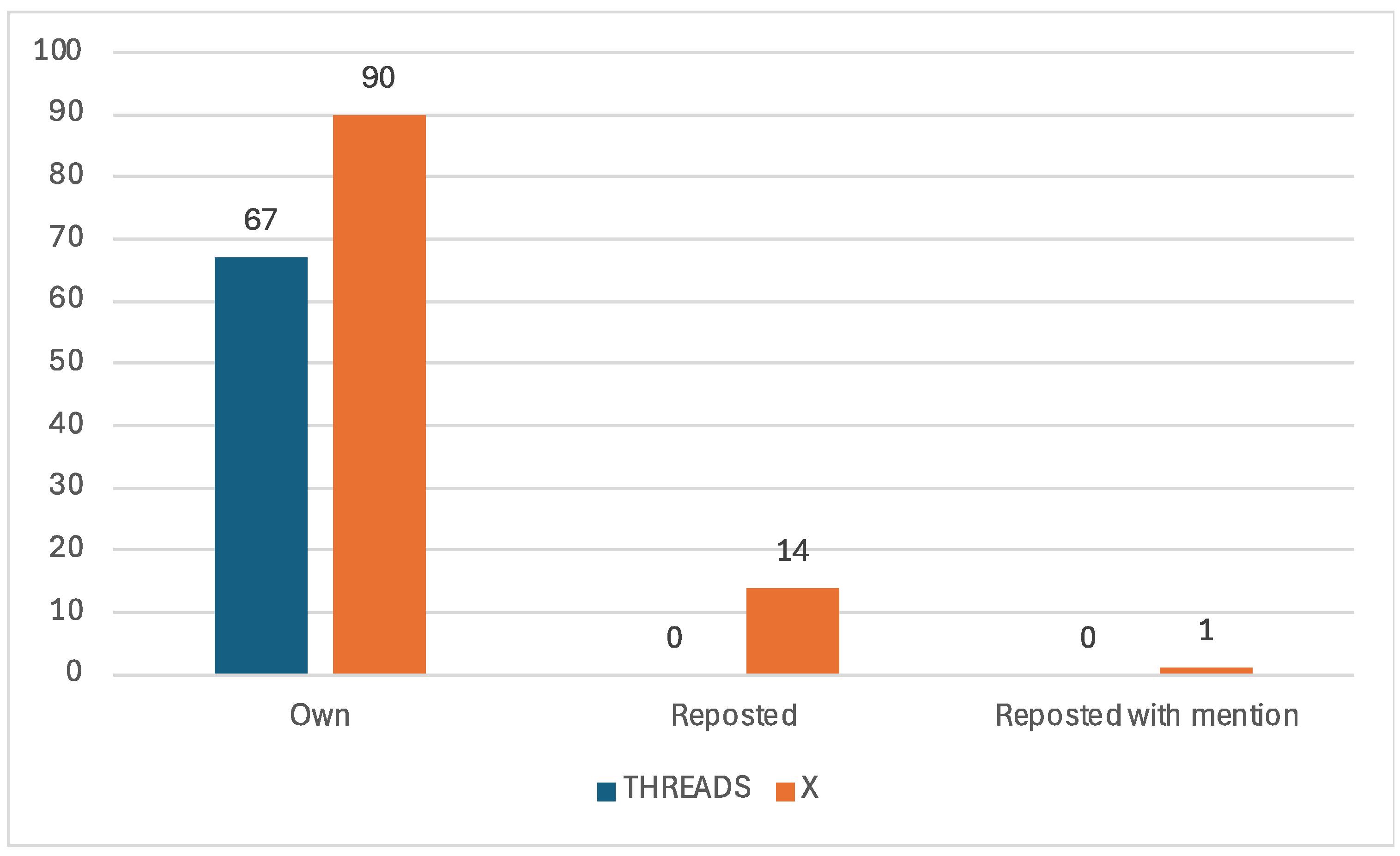

5.1. Types of Posts

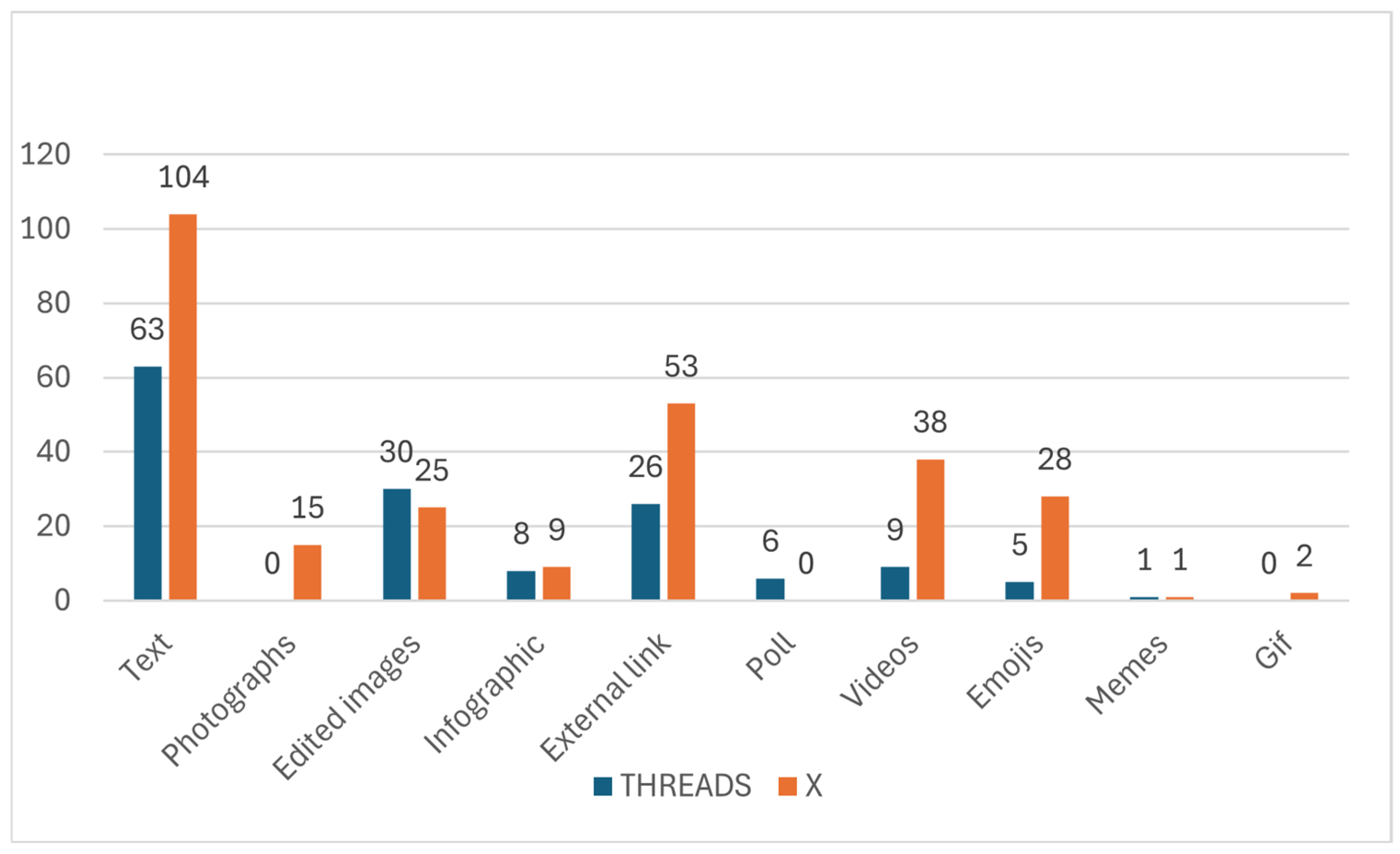

5.2. Multimedia Resources

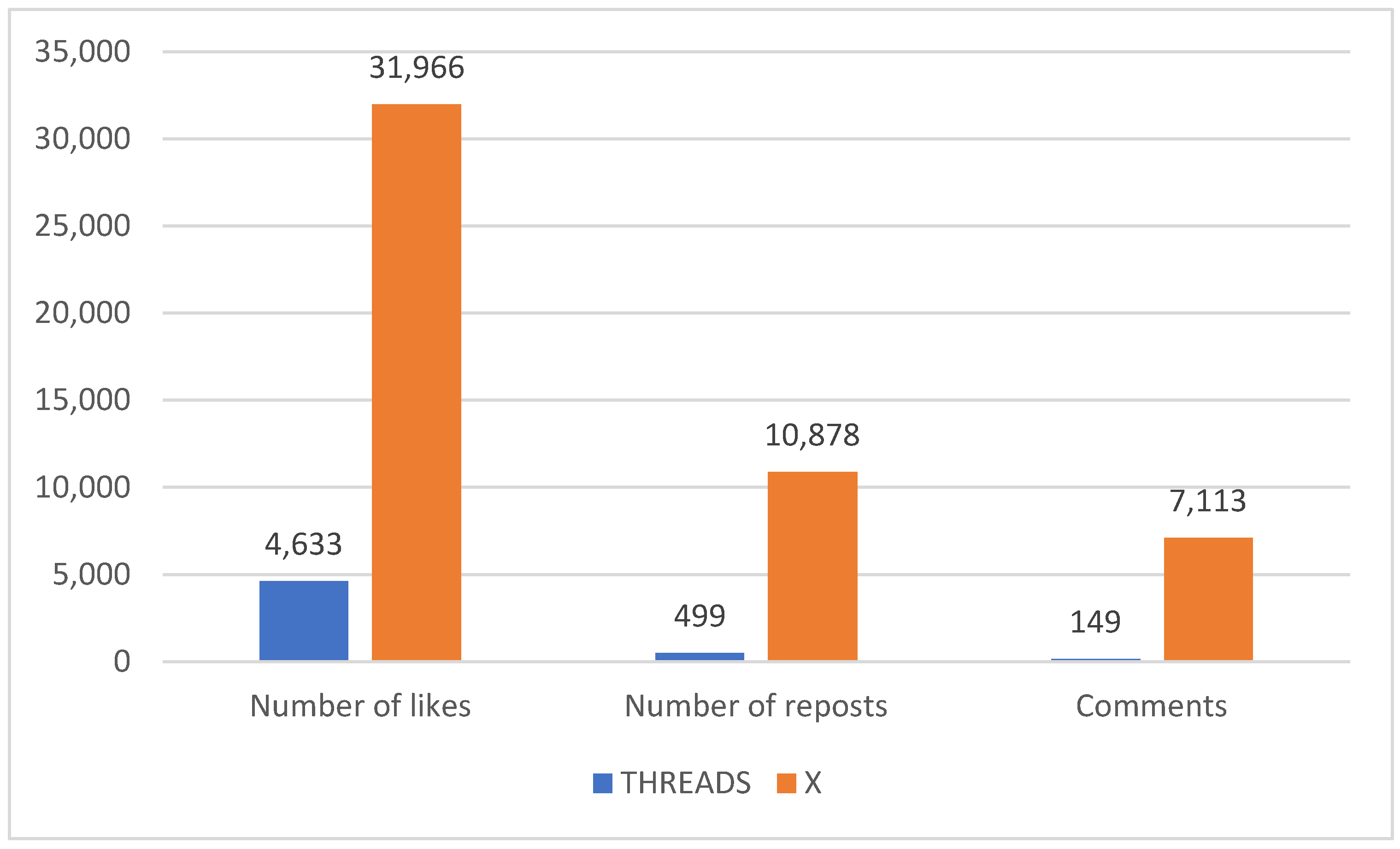

5.3. Interactions on the Accounts

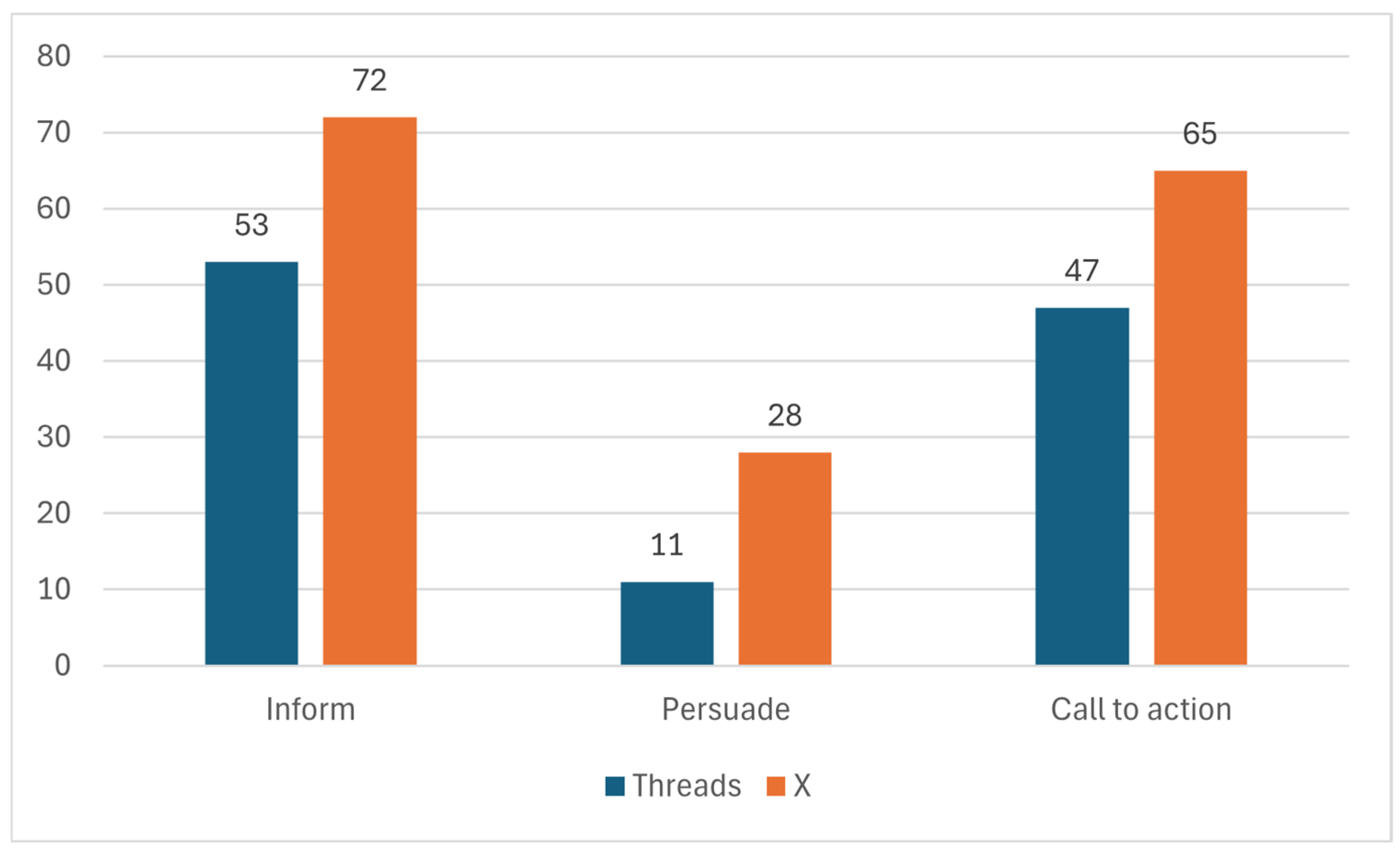

5.4. Message Intent

6. Discussion

6.1. Audience Fragmentation and Algorithmic Logic

6.2. Emotionality and Virality in Political Communication

6.3. Disinformation and Algorithmic Manipulation

6.4. Institutional Communication Strategies in the Digital Era

6.5. Conclusions

7. Conclusions

7.1. Key Findings and Insights

7.2. Strategic Implications for Institutional Digital Communication

- (1)

- Enhancing cross-platform coordination without losing differentiation: While distinct messaging strategies for X and Threads are valuable, ensuring better content synchronization where relevant could strengthen message consistency and reinforce institutional narratives. And developing a complementary posting strategy—where Threads serves as an informative hub while X maximizes engagement through real-time interactions—could enhance the effectiveness of institutional messaging.

- (2)

- Leveraging the unique strengths of each platform: X should continue to be the primary space for high-engagement political discourse, utilizing videos, mentions, and reposts to drive visibility and mobilization. Threads should be optimized for credibility and transparency, emphasizing fact-based communication, infographics, and structured posts to counter misinformation and foster civic awareness.

- (3)

- Expanding multimedia and interactive strategies on threads: while X benefits from the virality of video content, Threads’ engagement potential could be improved by introducing more interactive formats, such as explainer graphics, polls, and Q&A sessions.

- (4)

- Strategic content scheduling for maximum impact: Identifying and aligning optimal posting times on each platform can enhance audience engagement and content visibility. And utilizing data-driven scheduling approaches could improve content reach across different demographic segments.

- (5)

- Moving beyond traditional engagement metrics: Instead of focusing solely on likes, shares, and reposts, engagement should be measured by qualitative factors, such as policy impact, discourse longevity, and audience sentiment analysis. Threads, despite lower overall interaction levels, could serve as a repository for structured political communication, complementing the more fast-paced, reaction-driven engagement on X.

7.3. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2023). The appeal to emotions in the discourse of populist political actors from Spain, Italy, France and the United Kingdom on Twitter. Frontiers in Communication, 8, 1159847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2024). El rol de la ciudadanía en la conversación política en X. El caso de la #MocionDeCensura de 2023 en España. Revista Mediterránea De Comunicación, 15(2), e26829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, S., Nielsen, R., & Fletcher, R. (2022). The impact of news media and digital platform use on awareness of and belief in COVID-19 misinformation. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold-Forster, T. (2023). Walter lippmann and public opinion. American Journalism, 40(1), 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, M., Magin, M., Haßler, J., Russmann, U., Lilleker, D., Kruschinski, S., Jackson, D., Fenoll, V., Farkas, X., Baranowski, P., & Balaban, D. (2025). Populism in context: A cross-country investigation of the Facebook usage of populist appeals during the 2019 European parliament elections. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 30(1), 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bíró-Nagy, A., & Szászi, Á. J. (2024). The roots of Euroscepticism: Affective, behavioural and cognitive anti-EU attitudes in Hungary. Sociology Compass, 18(4), e13200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleyer-Simon, K., Polyak, G., & Urban, A. (2024). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era—Application of the media pluralism monitor in the European member states and candidate countries in 2023. Country report. Hungary, European University Institute. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2870/378835 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Borz, G., & De Francesco, F. (2024). Digital political campaigning: Contemporary challenges and regulation. Policy Studies, 45(5), 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, E., & Strömbäck, J. (2024). Misinformation, disinformation, and fake news: Lessons from an interdisciplinary, systematic literature review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 48(2), 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Domínguez, E., Esteve-del-Valle, M., & Renedo-Farpón, C. (2022). Rhetoric of parliamentary disinformation on Twitter. Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal, 30(72), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A., Tuñón, J., & Bouza-García, L. (2023). The European approach to online disinformation: Geopolitical and regulatory dissonance. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, Ł. D., & Suska, M. (Eds.). (2022). The European Union digital single market: Europe’s digital transformation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, C. E. (2018). The cosmopolitan-parochial divide: Changing patterns of party and electoral competition in the Netherlands and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(11), 1541–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, M., Rodríguez Castro, M., & Aslama Horowitz, M. (2024). Public service media and platformization: What role does EU regulation play? Journalism and Media, 5(3), 1378–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B., Peng, M. H., Chen, C. C., & Sun, S. L. (2022). Role of infodemics on social media in the development of people’s readiness to follow COVID-19 preventive measures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Orosa, B. (2021). Disinformation, social media, bots, and astroturfing: The fourth wave of digital democracy. Profesional De La Información, 30(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, P. (2018). Social media and populism: An elective affinity? Media. Culture & Society, 40, 745–753. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaudo, P. (2024). TikTok and the algorithmic transformation of social media publics: From social networks to social interest clusters. New Media & Society, 14614448241304106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosztonyi, G. (2023). Towards a digital agenda for the European Union 2020. In Censorship from plato to social media. Law, governance and technology series (Vol. 61). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosztonyi, G. (2024). How the European Union had tried to tackle fake news and disinformation with soft law and what changed with the digital services act? Frontiers in Law, 3, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, E., & Theviot, A. (2024). Social media, electoral politics, and political personalization in Indonesia. In Elections and social networks around the world (pp. 247–259). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Happer, C., & Philo, G. (2013). The role of the media in the construction of public belief and social change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmond, A. (2015). The platformization of the web: Making web data platform ready. Social Media + Society, 1, 2056305115603080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husovec, M. (2024). Principles of the digital services act. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kettemann, M. C., & Schulz, W. (Eds.). (2023). Platform://Democracy: Perspectives on platform power, public values and the potential of social media councils. Verlag Hans-Bredow-Institut. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H. (2016). The crisis of public service broadcasting reconsidered. In Performing legitimacy: Studies in high culture and the public sphere (pp. 79–99). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R., Jia, C., Wei, J., Xu, G., & Vosoughi, S. (2022). Quantifying and alleviating political bias in language models. Artificial Intelligence, 304, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. (2022). How to avoid the pseudo environment of users’ knowledge contribution?—Taking the online question and answer platform as an example (Vol. 8, pp. 10–15). Voice of the Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, B. (2017). An introduction to political communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, B. (2023). Images of the enemy: Reporting the new cold war. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Nieborg, D. B., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society, 20, 4275–4292. [Google Scholar]

- Nieborg, D. B., Poell, T., & Deuze, M. (2019). The platformization of making media. In Making media: Production, practices, and professions (pp. 85–96). Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nulty, P., Theocharis, Y., Popa, S. A., Parnet, O., & Benoit, K. (2016). Social media and political communication in the 2014 elections to the European Parliament. Electoral Studies, 44, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, C., & Velasco Molpeceres, A. M. (2020a). Impacto del discurso político en la difusión de bulos sobre COVID-19. Influencia de la desinformación en públicos y medios. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, 78, 86–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, C., & Velasco Molpeceres, A. M. (2020b). Tendencia y narrativas de fact-checking en Twitter. Códigos de verificación y fake news en los disturbios del Procés (14-O). Adcomunica, 20, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & Van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahreza, M. (2024). Global perspectives of digital political communication. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunjak, M. (2016). Monitoring political independence of public service media: Comparative analysis across 19 European Union Member States. Journal of Media Business Studies, 13, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, V. (2024). Social media and Indian politics: Its Evolution through history to the catalyst, influencer and contender in 21st century. International Journal of Law Management & Humanities, 7(1), 2556. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/ijlmhs27&div=214&id=&page= (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Tardy, C. M. (2022). How epidemiologists exploit the emerging genres of Twitter for public engagement. English for Specific Purposes, 70, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teneva, E. V. (2023). Digital pseudo-identification in the post-truth era: Exploring logical fallacies in the mainstream media coverage of the COVID-19 vaccines. Social Sciences, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnberg, P., & Törnberg, A. (2024). Inside a White Power echo chamber: Why fringe digital spaces are polarizing politics. New Media & Society, 26(8), 4511–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenz, H. J., Heft, A., Vaughan, M., & Pfetsch, B. (2021). Resilience of public spheres in a global health crisis. Javnost—The Public, 28(2), 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J. A., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón Navarro, J., & Sánchez del Vas, R. (2022). Verificación: ¿la cuadratura del círculo contra la desinformación y las noticias falsas? AdComunica, 23, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, F., & Enyedi, Z. (2024). They can do it. Positive authoritarianism in Poland and Hungary. Frontiers in Political Science, 6, 1390587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C. (2023). Misunderstanding misinformation. Issues in Science and Technology, 39(3), 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Gevers, J., & Rossi, L. (2023). “Can I write this is ableist AF in a peer review?”: A corpus-driven analysis of Twitter engagement strategies across disciplinary groups. Ibérica, (46), 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinnbauer, D. (2021). Nurturing the integrity of political communication in the digital era. Open Government Partnership. Available online: https://www.agora-parl.org/sites/default/files/agora-documents/Nurturing%20the%20Integrity%20of%20Political%20Communication%20in%20the%20Digital%20Era_An%20OGP%20Perspective.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Zuhdi, A., Suryana, C., Pedrason, R., Sasono, S., & Habibie, A. M. (2023). Digital campaign: Character branding and framing towards the 2024 presidential election. Al Qalam: Jurnal Ilmiah Keagamaan dan Kemasyarakatan, 17(1), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velasco Molpeceres, A.; Miranda-Galbe, J.; Prieto Muñiz, M. Digital Political Communication in the European Parliament: A Comparative Analysis of Threads and X During the 2024 Elections. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010042

Velasco Molpeceres A, Miranda-Galbe J, Prieto Muñiz M. Digital Political Communication in the European Parliament: A Comparative Analysis of Threads and X During the 2024 Elections. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelasco Molpeceres, Ana, Jorge Miranda-Galbe, and María Prieto Muñiz. 2025. "Digital Political Communication in the European Parliament: A Comparative Analysis of Threads and X During the 2024 Elections" Journalism and Media 6, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010042

APA StyleVelasco Molpeceres, A., Miranda-Galbe, J., & Prieto Muñiz, M. (2025). Digital Political Communication in the European Parliament: A Comparative Analysis of Threads and X During the 2024 Elections. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010042