Suicide of Minors in the Spanish Press: Analysis from the Perspective of Public Interest and the Limits of Freedom of Information

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Incidence of Suicide in Childhood and Adolescence

1.2. Media Silence and Self-Censorship

1.3. The Public Interest of Suicide from a Juridical Perspective

“the general interest of an abstract debate should not be confused with the public relevance of the specific information disclosed; nor should the curiosity fueled by the media, by attributing a news value to the publication of the images that are the subject of controversy, be confused with a public interest worthy of constitutional protection.”

“the public relevance of certain information must not be confused with its newsworthiness, since it is not the media that are called upon by the Spanish Constitution to determine what is or is not of public relevance, nor can this be confused with the diffuse object of a non-existent right to satisfy the curiosity of others.”

1.4. Objective: The Public Interest of Suicide in Minors

“… as made possible by art. 20.4 CE and within the framework of the principles and values that inform our Fundamental Rule, Organic Law 1/1982, of May 5, on the Civil Protection of the Right to Honor, Privacy and Self-Image, establishes that the memory of a deceased person may limit the right to the communication of truthful information.”

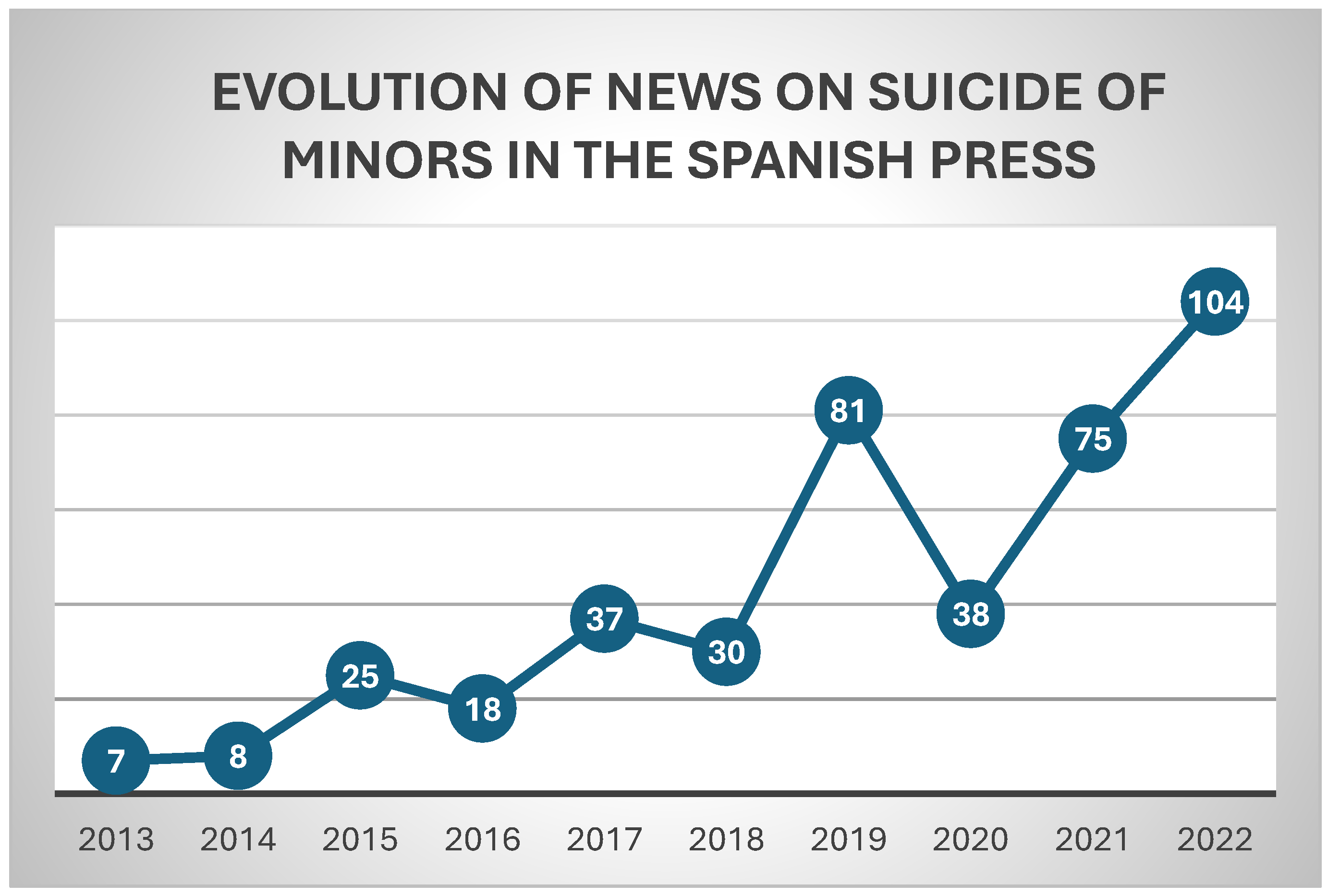

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results: Analysis of Suicide News in Minors from the Perspective of Public Interest and the Limits of Freedom of Information

- An upward trend in suicidal behavior, mental health and suicide of minors during and after the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Initiatives to prevent suicide in minors;

- Suicide of minors related to bullying;

- Suicide of minors linked to sexual abuse or harassment;

- Suicide of minors and the use of social networks.

3.1. News on the Increase in Suicidal Behavior in Minors

Psychiatrists and judges warn of the rise in suicide attempts among minors in the Basque CountryThe emotional impact of the pandemic could be behind the 60% increase in admissions for mental health problems among adolescents(El Correo, 23 May 2021)

Anxiety disrupts the lives of children and young peoplePsychiatric emergencies in minors have skyrocketed since the beginning of the pandemic. Depression and suicide attempts are intensifying among young people who are increasingly disarmed by frustration and uncertainty.“We have gone from four suicide attempts a week by young people to more than 20.”(El País, 21 June 2021)

Isabel Flórez, director of the Balearic Institute of Mental Health for Children and Adolescents: “We have seen fifty suicide attempts in minors since August”“Hospital admissions for suicide attempts and eating disorders have increased by 70% until September”(Diario de Mallorca, 10 October 2021)

“We are experiencing a record avalanche of consultations on suicides in Seville, especially girls and adolescents.”Miguel Ruiz Veguilla, psychiatrist and coordinator of the suicide prevention plan of the Virgen del Rocío Hospital, warns about the deterioration of mental health that the pandemic could have aggravated(ABC, 26 December 2021)

Francisco Villar: “Suicide attempts among minors increased by 300% in 2021”This psychologist from Sant Joan de Déu Hospital calls for mobilization against this problem (aggravated by COVID-19), as was done with road traffic accidents(El Periódico, 23 April 2022)

Youth suicide, a public health problemSuicide attempts in minors reach the highest number in the last ten years(La Vanguardia, 5 December 2022)

3.2. News on Prevention Initiatives

Talking about suicide in schools, yes or no? The debate is onMental health professionals explain that preventing this type of behavior is betting on life, “not on a contagion effect”(ABC, 13 March 2019)

Barcelona opens a WhatsApp line to prevent suicide among young peopleSuicide attempts attended by hospitals have doubled in the last 6 months in Catalonia.(La Vanguardia, 25 May 2021)

Signs to detect the risk of youth suicideThere are verbal and behavioral warning signs(Las Provincias, 20 August 2021)

Eight hospitals test first national pilot plan to reduce teen suicide attempts: “The spike in girls is alarming”Since 2006, attempts have tripled and exceeded 2000 per year. The Survive research project analyzes the effects of a six-session therapy on Spanish youths aged 13 to 18 who have already attempted to take their own lives.(El País, 12 August 2022)

3.3. News on Suicide and School Bullying

The Public Prosecutor’s Office charges two girls for Carla’s suicideThe teenager took her own life at the age of 14 in Gijón after a course of bullying at school The persecution that ended her life could constitute a crime against moral integrity “They called her cross-eyed, a lesbian and they poured water from the toilet over her”(El Mundo, 25 September 2014)

“May my daughter’s suicide serve to make bullying a crime, not a simple misdemeanor.”Monserrat Magnien, Carla’s mother, also calls for teachers to know how to detect school bullying(ABC, 23 February 2015)

A disabled teenager commits suicide after being bullied at school.(…) She said goodbye to her friends by WhatsApp and jumped from the sixth floor of her block of apartments.(…) The minor, with intellectual and motor disabilities, told her teachers that another student at the center demanded money and coerced her with messages.“I’m tired of living”, the girl wrote in a phone message to her friends before throwing herself down the stairwell.(El País, 23 May 2015)

Another teenager charged in connection with Arancha’s suicideThe Juvenile Prosecutor’s Office has charged a teenager related to the suicide of the girl who was allegedly bullied at the Ciudad de Jaén high school in Usera.(La Razón, 28 June 2015)

A suicide letter, key in the arrest of the classmate accused of bullying(…) Andrés had not appeared in class since Wednesday, March 27, but it was on Monday, April 1, when he decided to take his own life at home.(ABC, 5 April 2019)

The suicide note of Andrés, the minor who was being bullied: “I had to endure six hours of fear”(…) The three pages in the possession of the National Police and reproduced in the article were decisive for the agents to question his classmates and arrest the 17-year-old who supposedly made his life impossible and who days before taking his own life stole his mobile phone and keys.(…)The young man begins his shocking story like this: “My name is Andrés and if you are reading this it is because I must have committed suicide.” “The fact is that everything started well until February 2019, when I fell into a nosedive. I had to endure six hours in which little by little I began to feel more afraid and that was my last month of life. I knew I was alone, that no one would help me.”(El Mundo, 11 April 2019)

Diego, 11 years old, before committing suicide: “I can’t stand going to school” This is how Carmen González remembers the moment she discovered that her son Diego, 11 years old, had just thrown himself out of the window from the fifth floor of the family home: […] “I searched like crazy all over the house and I saw, at the back of the kitchen, the open screen, I went over and… In the darkness I saw his shadow, on the floor. We live on the fifth floor.”(El Mundo, 20 January 2016)

Madrid reviews the suicide of a minor for possible school bullying“I can’t stand going to school and there’s no other way not to go”, Diego left written in a letter to his parents(El País, 21 January 2016)

Suicide of a teenager investigated for possible ‘bullying’ at a school in BarcelonaThe parents of the minor denounce the school Pare Manyanet school before the Mossos and the Síndic de Greuges (Catalan Ombudsman).(La Vanguardia, 10 June 2021)

One year after Kira’s suicide: “Our life ended then”The Mossos, Educació and the Ombudsman are still investigating whether the student from Pare Manyanet de Sant Andreu was suffering from bullying, as her parents claim The Regional Ministry and Barcelona City Council have appeared as a popular prosecution in the case investigating these events(El Periódico, 18 May 2022)

“includes not only information that is considered harmless or indifferent, or that is welcomed, but also information that may cause concern to the State or to a part of the population, as this is the result of pluralism, tolerance and the spirit of openness without which a democratic society cannot exist.”

“it is unquestionable that the legitimate interest of minors in not disclosing data relating to their personal or family life is part of the same, which is established, as set out in of the provisions of art. 20.4 EC, as an insurmountable limit to the exercise of the right to freely communicate truthful information.”

Saray’s suicide attempt: a leap into the void in the face of school bullying and silence.The parents of the 10-year-old girl who jumped from the balcony in Zaragoza denounce the passivity of her school in the face of bullying. “Neither ‘bullying’ nor ‘bullan’”, said the tutor.The call surprised Carlos Amezquita on the Mudéjar highway, on his way to Teruel: “Saray has jumped!” his wife shouted. With difficulty, the man managed to understand that his 10-year-old daughter had jumped from the balcony of the house, on a third floor. (…). “It was the worst half hour of my life”, he recounts from the corridor of the Miguel Servet hospital, where Saray is recovering from a fall that could have killed her, but only broke her hip and injured her left ankle.(El País, 18 September 2022)

Classmates and a teacher prevent a student from committing suicide in classThe acting president of the Community asks parents to remain “calm” and assures that “numerous controls” are being implemented in the high schools(ABC, 15 April 2019)

A father blames the high school for the suicide attempt of his 14-year-old son, who is being bullied at schoolThe family found the minor in his room, unconscious and with wounds on his wrists—They claim that the bullying has been continuous since he entered the Mutxamel high school last year(Información, 14 February 2020)

“In short, in order for the capture, reproduction or publication by photograph of the image of a minor in the media to not be considered an illegitimate interference in his or her right to his or her own image (art. 7.5 of Organic Law 1/1982), the prior and express consent of the minor (if he or she is old enough and mature enough to give it), or of his or her parents or legal representatives (art. 3 of Organic Law 1/1982) will be necessary, although even such consent will be ineffective to exclude the violation of the minor’s right to his or her own image if the use of his or her image in the media may imply damage to his or her honor or reputation, or be contrary to his or her interests (art. 4.3 of Organic Law 1/1996).”

A mother’s heartbreaking message after her son’s suicide due to bullying: “No signs, just hurtful words”.A family shares their grief on social media after their son was bullied by a classmate for more than a year“This… this is the result of bullying, my beautiful son was fighting a battle that we have not been able to save him from. It’s real, it’s silent and there is absolutely nothing as a parent you can do. There are no signs, just hurtful words from others who have finally stolen our Drayke from us.” This is the beginning of the heartbreaking message that a mother has posted on social media accompanied by several photos of her entire family with the lifeless body of her son, with the aim of raising awareness among those who read the message. Drayke was only 12 years old, but he could no longer stand the bullying he received in class.(ABC, 16 February 2022)

A mother’s message after her son’s suicide due to bullying: “How can a 12-year-old boy loved by everyone think that life is so difficult that he needs to get out of it?”Samie Hardman, a mother from Utah (United States) has shared on her Instagram account some photographs in which she and her family say goodbye to her son Drayke, 12 years old, who has committed suicide due to the bullying he suffered.(El Mundo, 16 february 2022)

“certain events that may occur to parents, spouses or children have, normally, and within the cultural patterns of our society, such transcendence for the individual, that their undue publicity or diffusion has a direct impact on the sphere of his own personality. Therefore, there exists in this respect a right—proper and not alien—to privacy, constitutionally protectable.”

3.4. News on Suicide and Abuse of Minors

Suicide of another minor in Morocco forced to marry an older manThe 17-year-old girl used a rat poison, just like Amina Filali, forced in 2012 to marry her rapist(ABC, 28 January 2014)

Prison for a young man for alleged sexual assault related to the suicide of a minorAccording to the Superior Court of Justice of Aragon (TSJA), the detainee was apparently the half-brother of the girl who threw herself from the viaduct in Teruel.(El Periódico de Aragón, 28 June 2019)

A new night of anger in Colombia: Popayán erupts after the suicide of a minor detained by the policeIván Duque sends his Defense and Interior ministers to that city to quell the riots and clarify the death of the young woman, who took her own life after accusing some agents of sexual abuse(El País, 15 May 2021)

Jury convicts man of manslaughter for suicide of a minor after sending him 119 harassing messagesThe defendant “was aware of the distress he was causing” the 17-year-old boy who killed himself in 2016 but did not let up on his WhatsApp threats. The prosecutor asks for 14 years in prison(…) According to the jury, in addition to the conviction for homicide, the convicted should have the aggravating circumstance of superiority applied to him, since Paradís knew that the person he was talking to was a minor “and he expressly and specifically took advantage of such a situation, knowing and being aware of the immaturity and vulnerability of the minor.”(El País, 27 July 2022)

“in general, the existence of newsworthy events in events of criminal relevance, regardless of the status of private subject of the person or persons affected by the news (…). the information on the positive or negative results achieved in their investigations by the State security forces and corps is of public relevance or interest, especially if the crimes committed involve a certain gravity or have caused a considerable impact on public opinion, extending that relevance or interest to any new data or facts that may be discovered, by the most diverse means, in the course of the investigations aimed at clarifying the authorship, causes and circumstances of the criminal act.”

“there is no doubt that events of criminal relevance should be considered newsworthy events (…) regardless of the private nature of the person affected by the news (…) but such consideration cannot include the individualisation, directly or indirectly, of those who are victims of the events, unless they have allowed or facilitated such general knowledge. Such information is no longer of public interest, as it is unnecessary to transmit the information intended.”

3.5. News on Suicide of Minors and Social Media

A French victim of cyberbullying tells of her suicide attempt at the Vatican.(…) Laetitia Chanut, was 17 years old and was very popular both at her school in Albi and among the 400 friends on her Facebook page when, suddenly, as she recounted “I discovered that someone had created a dozen accounts just like mine: same photo, same name, same appearance… And I had written to all my friends to ask: ‘Hello, have you seen my porn video?’ A video that evidently does not exist!”.(ABC, 9 December 2024)

Minors commit suicide if they are impersonated onlineYoung people attach so much importance to their “digital identity” that they confuse it with their real identity(La Razón, 8 May 2015)

14-year-old girl commits suicide live on air and her mother mocks herNakia Venant was in foster care when she hanged herself with a scarf before the eyes of hundreds of onlookers, including her parent, on 22 January 2016(El Periódico, 16 March 2017)

A mother in the United States discovers suicide advice for children hidden in YouTube Kids videosThe woman alerted about the content on her blog and got YouTube to remove it(La Vanguardia, 25 February 2019)

Police prevent the suicide of a minor who posted her intentions on TikTokThe National Police have prevented the suicide of a minor who had published her intentions on the social media TikTok and who at the time of being located in a town near Benidorm (Alicante) had cut marks on both wrists.(La Vanguardia, 30 December 2020)

“with certain exceptions, even if citizens voluntarily share personal data on the Internet, they continue to have their own private sphere, which must remain separate from the millions of users of social media on the Internet, unless they have given their unequivocal consent to be observed or to have their image used and published.”

The dangerous ‘Blue Whale’ arrives in Spain: a minor is admitted to a psychiatric hospitalThe 15-year-old girl followed the 50 challenges of the game that invites people to commit suicide. The ‘Blue Whale’ has arrived in Spain. It is a role-play game in which, through fifty tests, those who participate in it must follow challenges that end with suicide. A Catalan minor has been admitted to a psychiatric hospital for participating in it.(Ideal, 28 April 2017)

“I love you but I have to follow the man in the hood”: the suicide of a child that shocks ItalyThe minor left a note and jumped from the balcony of his room, on the 11th floor of a building in NaplesThe Jonathan Galindo challenge uses a sinister image that went viral 10 years ago but serves as a lure for younger victims(La Razón, 30 September 2020)

Alert in Valencia after the suicide of a minor and the attempt of another in just 12 hThe National Police investigates if there is any connection between the two boys and if their action is related to some virtual challenge(Levante, 9 February 2021)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ANAR Foundation’s Research and Studies Center. (2022). Conducta suicida y salud mental en la infancia y la adolescencia en España 2011–2022. Available online: https://www.anar.org/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Beam, R. A., John, S. L., & Yaqub, M. M. (2018). “We don’t cover suicide… (except when we do cover suicide)”: A case study in the production of news. Journalism Studies, 19(10), 1447–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Castilla, E., & Cano-Galindo, J. (2019). School bullying and teen suicide in the Spanish press: From journalistic taboo to boom. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, 74, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras Serra, L. (2008). Las normas jurídicas de los periodistas: Derecho español de la información. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. [Google Scholar]

- Cerel, J., Brown, M. M., Maple, M., Singleton, M., van de Venne, J., Moore, M., & Flaherty, C. (2019). How many people are exposed to suicide? not six. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(2), 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constitución Española. (1978). Cortes Generales de España. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 29 de diciembre de 1978. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1978-31229 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Crosby, A., Ortega, L., & Melanson, C. (2011). Self-directed violence surveillance; uniform definitions and recommended data elements. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (U.S.). Division of violence prevention. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11997 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Everymind. (2020). Reporting suicide and mental ill-health: A mindframe resource for media professionals. Available online: https://mindframe.org.au/suicide (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Fortea, A., Fortea, L., Gómez-Ramiro, M., Fico, G., Giménez-Palomo, A., Sagué-Vilavella, M., Pons, M. T., Vázquez, M., Baldaquí, N., Colomer, L., Fernández, T. M., Gutiérrez-Arango, F., Llobet, M., Pujal, E., Lázaro, L., Vieta, E., Radua, J., & Baeza, I. (2023). Upward trends in eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide attempt emergency admissions in female adolescents after COVID-19 lockdown. Spanish Journal of Psychiatry and Mental Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, D., Marcos del Cano, A. M., & Topa, G. (2024). Suicidio e interés público en la prensa española: Análisis desde la jurisprudencia constitucional sobre libertad de información/Suicide and public interest in the Spanish press: Theoretical analysis from the constitutional jurisprudence on freedom of information. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 57, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerl, U., Wittenburg, L., Arensman, E., Van Audenhove, C., Coyne, J. C., McDaid, D., Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. V. D., Gusmão, R., Kopp, M., Maxwell, M., & Meise, U. (2009). Optimizing suicide prevention programs and their implementation in Europe (OSPI Europe): An evidence-based multi-level approach. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2024). Death statistics by cause of death. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Jamieson, P., Jamieson, K. H., & Romer, D. (2003). The responsible reporting of suicide in print journalism. The American Behavioral Scientist (Beverly Hills), 46(12), 1643–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomek, A. B., Sourander, A., & Gould, M. (2010). The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: A review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(5), 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley Orgánica 1/1996, de 15 de enero, de Protección Jurídica del Menor, de modificación parcial del Código Civil y de la Ley de Enjuiciamiento Civil. (1996). Cortes Generales de España. BOE núm. 15, de 17/01/1996. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1996-1069 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Ley Orgánica 8/2021, de 4 de junio, de protección integral a la infancia y la adolescencia frente a la violencia. (2021). Cortes Generales de España. BOE núm. 134, de 05/06/2021. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2021-9347 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Machlin, A., Pirkis, J., & Spittal, M. J. (2013). Which suicides are reported in the media—and what makes them “newsworthy”? Crisis, 34(5), 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciá-Casas, A., de la Iglesia-Larrad, J., García-Ullán, L., Refoyo-Matellán, B., Munaiz-Cossío, C., Díaz-Trejo, S., Berdión-Marcos, V., Calama-Martín, J., Roncero, C., & Pérez, J. (2024). Post-Pandemic Evolution of Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents Attending a General Hospital Accident and Emergency Department. Healthcare, 12(10), 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac Quail, D. (1998). La acción de los medios: Los medios de comunicación y el interés público. Amorrortu. [Google Scholar]

- Medina Guerrero, M. (2005). La protección constitucional de la intimidad frente a los medios de comunicación (pp. 13–20). Tirant lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. (2020). Recomendaciones para el tratamiento del suicidio por los medios de comunicación. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Niederkrotenthaler, T., Voracek, M., Herberth, A., Till, B., Strauss, M., Etzersdorfer, E., Eisenwort, B., & Sonneck, G. (2010). Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. papageno effects. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 197(3), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noriega, D. (2019, March 5). El silencio sobre el suicidio perpetúa la primera causa de muerte no natural en España. ElDiario. Available online: https://is.gd/T5kupC (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- O’Connor, R. C., Platt, S., & Gordon, J. (2011). International handbook of suicide prevention: Research, policy and practice. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Olmo López, A., & García-Fernández, D. (2015). Suicidio y libertad de información: Entre la relevancia pública y la responsabilidad. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 38, 70–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paricio-del Castillo, R., del Sol-Calderón, P., García-Murillo, L., Mallol-Castaño, L., Pascual-Aranda, A., & Palanca-Maresca, I. (2024). Suicidio infanto-juvenil tras la pandemia de COVID-19: Análisis de un fenómeno trágico. Revista de la Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría, 44(145), 19–45. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0211-57352024000100002 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Pérez, M. (2017, September 10). Hay que hablar del suicidio como se habla de la neumonía. El Mundo. Available online: https://is.gd/x4IncP (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Phillips, D. P. (1974). The influence of suggestion on suicide: Substantive and theoretical implications of the Werther effect. American Sociological Review, 39(3), 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J., Burgess, P., Blood, R. W., & Francis, C. (2007). The newsworthiness of suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(3), 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J., & Nordentoft, M. (2011). Media influences on suicide and attempted suicide. In R. O’Connor, S. Platt, & J. Gordon (Eds.), International handbook of suicide prevention: Research, policy and practice (pp. 531–544). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, R. (2009). Los medios de comunicación y la concienciación social en España frente al acoso escolar/The media and social awareness Spain face of harassment in school. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodistico, 15, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Samaritans. (2020). Media guidelines for reporting of suicides. Available online: https://www.samaritans.org (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Shneidman, E. (1972). Foreword. In A. Cain (Ed.), Survivors of suicide (pp. ix–xi). Charles C. Thomas. [Google Scholar]

- Tribunal Constitucional. (1982). Sentencia núm. 62/1982, de 15 de octubre de 1982. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/104 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (1986). Sentencia núm. 159/1986, de 16 de diciembre de 1986. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/722 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (1988). Sentencia núm. 231/1988 de 2 de diciembre de 1988. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/1172 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (1992). Sentencia núm. 20/1992, de 14 de febrero de 1992. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/1907 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (1995). Sentencia núm. 173/1995, de 21 de noviembre de 1995. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/3027 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (1996). Sentencia núm. 190/1996, de 25 de noviembre de 1996. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es/Resolucion/Show/3242 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (1999). Sentencia núm. 134/1999, de 15 de julio de 1999. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/3876 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (2000). Sentencia núm. 115/2000, de 5 de mayo de 2000. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/4099 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (2002a). Sentencia núm. 52/2002, de 25 de febrero de 2002. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/4588 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (2002b). Sentencia núm. 83/2002, de 22 de abril de 2002. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/4619 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (2003). Sentencia núm. 127/2003, de 30 de junio de 2003. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/4902 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (2009). Sentencia núm. 158/2009, de 25 de junio de 2009. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es-ES/Resolucion/Show/6577 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (2019). Sentencia núm. 25/2019, de 25 de febrero de 2019. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2019-4440 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tribunal Constitucional. (2020). Sentencia núm. 27/2020, de 24 de febrero de 2020. Available online: https://hj.tribunalconstitucional.es/es/Resolucion/Show/26246 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Turecki, G., & Brent, D. A. (2016). Suicide and suicidal behavior. The Lancet (British Edition), 387(10024), 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, G., Brent, D. A., Gunnell, D., O’Connor, R. C., Oquendo, M. A., Pirkis, J., & Stanley, B. H. (2019). Suicide and suicide risk. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 5(1), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urías, J. (2009). Lecciones de derecho de la información (2nd ed.). Tecnos. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2012). Public health action for the prevention of suicide. A framework. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241503570 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- World Health Organization. (2021). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global health estimates. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. (2023). Preventing suicide: A resource for media professionals, update. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240076846 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2024). Suicide Prevention. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- World Health Organization & International Association for Suicide Prevention. (2017). Preventing suicide: A resource for media professionals. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Fernández, D.; Marcos del Cano, A.M.; Topa, G. Suicide of Minors in the Spanish Press: Analysis from the Perspective of Public Interest and the Limits of Freedom of Information. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010035

García-Fernández D, Marcos del Cano AM, Topa G. Suicide of Minors in the Spanish Press: Analysis from the Perspective of Public Interest and the Limits of Freedom of Information. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Fernández, Diego, Ana M. Marcos del Cano, and Gabriela Topa. 2025. "Suicide of Minors in the Spanish Press: Analysis from the Perspective of Public Interest and the Limits of Freedom of Information" Journalism and Media 6, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010035

APA StyleGarcía-Fernández, D., Marcos del Cano, A. M., & Topa, G. (2025). Suicide of Minors in the Spanish Press: Analysis from the Perspective of Public Interest and the Limits of Freedom of Information. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010035