Attracting the Vote on TikTok: Far-Right Parties’ Emotional Communication Strategies in the 2024 European Elections

Abstract

1. Introduction

- SO1.

- Determine the predominant emotions in audiovisual messages (positive, negative, and neutral).

- SO2.

- Examine the recurring themes used to connect voters’ concerns or aspirations, especially young people.

- SO3.

- Analyse the stylistic and narrative resources used to generate emotional impact (music, language, visual effects, etc.).

- SO4.

- Determine the frequency and type of emotional content generated by the videos.

- SO5.

- Compare the strategies of the different leaders of the parties analysed.

- RQ1.

- Which emotions dominate the videos posted by the leaders of extreme right-wing parties on TikTok during the period analysed?

- RQ2.

- What are the most common themes found in the messages published on TikTok?

- RQ3.

- Which audiovisual resources are used to enhance the emotional impact, including music, editing, effects, and body language?

- RQ4.

- What is the magnitude of these messages, and how does it relate to affective polarisation (positive, negative, or neutral) in TikTok posts by far-right leaders?

- RQ5.

- What are the variations in emotional strategies based on the country or political leader?

- RQ6.

- What types of interactions are generated by videos containing emotional content, such as “likes”, comments, and shares?

- RQ7.

- Is there a correlation between the utilisation of particular emotions and the degree of engagement?

- RQ8.

- Are there any particular appeals to identity, cultural, or social values specifically aimed at young people?

- SH1:

- The messages disseminated by far-right party leaders on TikTok are designed with a style, content, and tone that specifically appeal to young audiences. They incorporate topics relevant to their interests and forms of communication characteristic of this demographic.

- SH2:

- Negative emotions such as fear, anger, and disgust dominate the analysed videos and are used as tools to polarise and mobilise the audience.

- SH3:

- Videos that integrate negative and unpleasant emotions generate a higher level of interaction and engagement than videos that lack these elements.

1.1. TikTok, a Vein for Political Communication Targeting Young People

1.2. Emotional Strategies for Political Communication

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

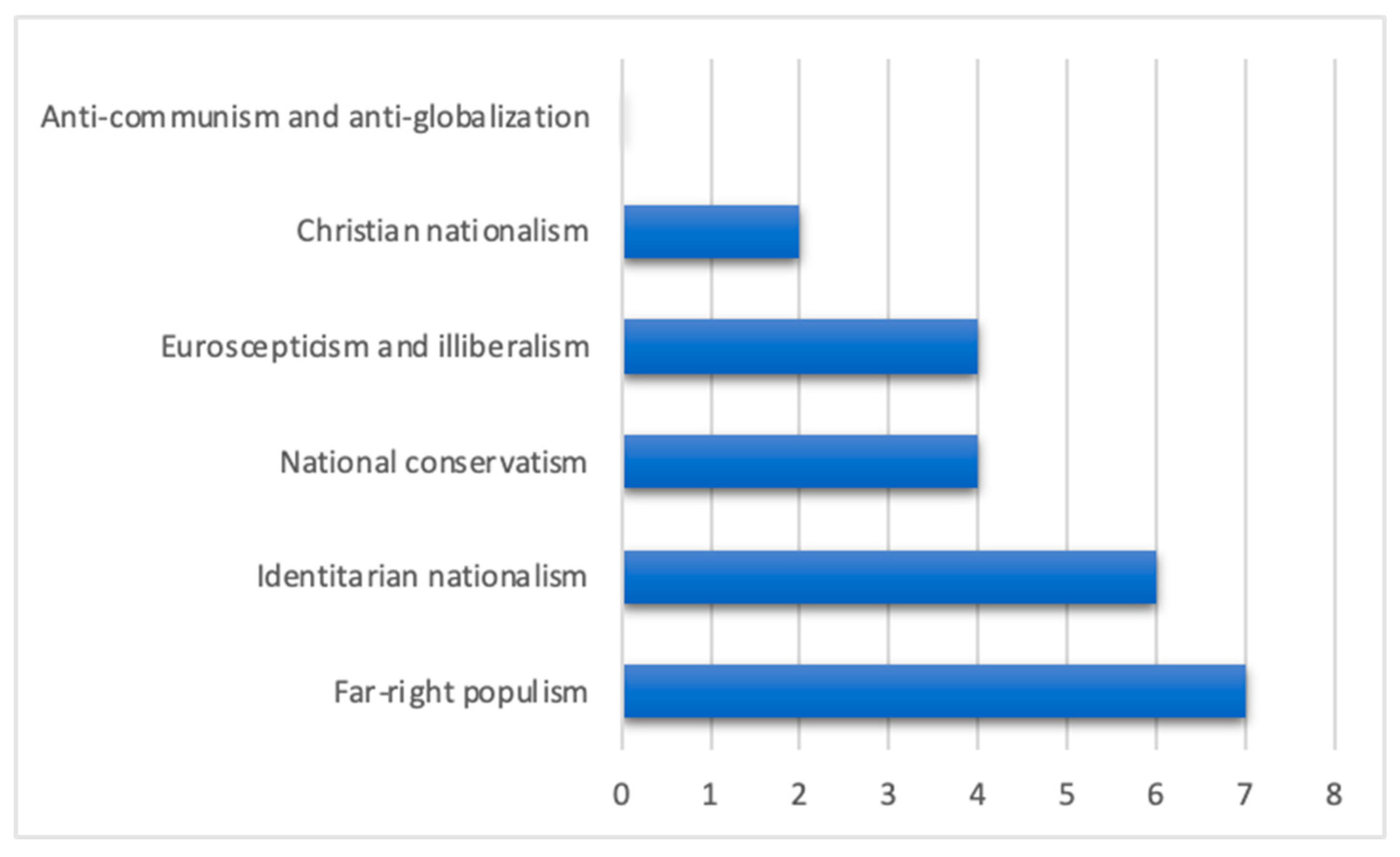

3.1. Contextualising the Party, the Leader and His TikTok Account

- —

- National symbolism and professionalism. Leaders such as Slawomir Mentzen and Marine Le Pen employ flags and official contexts in their photographs, thereby reinforcing their nationalist identity and connection to traditional values.

- —

- Closeness and spontaneity. Leaders such as Viktor Orbán or Jimmie Åkesson opt for a more casual and informal approach, incorporating photographs taken outdoors or with an active attitude. This aims to connect with young audiences and create a more accessible image.

- —

- Distinctive narrative style. Leaders such as Diana Șoșoacă stand out for their distinct character, combining populist messages with emotional and cultural content, such as in the case of music videos.

3.2. Content Analysis of European Far-Right Leaders’ TikTok Publications

3.2.1. Analysis of the Descriptive Variables

3.2.2. Analysis of the Variables of the Message and Its Emotional Content

3.2.3. Analysis of Stylistic and Technical Variables

- Absence of music. It is commonly used to convey feelings of disharmony, danger, and insecurity, as well as intense negative emotions. Music alone can be used to create a crudeness or realism effect that intensifies emotional perception.

- Neutral or ambient music. It appears to be associated with emotions of empathy and social connection, as well as with hope and illusion. This type of music has the potential to serve as a background that does not cause any distraction but rather complements and reinforces warmer and more emotional messages.

- Epic music. It is primarily related to emotions of pride and ambition and hope and illusion. Epic music emphasises emotions of achievement, grandeur, and optimism.

- Cheerful or lively music. It is more prevalent in positive emotions, such as hope and illusion, and less common in personal enjoyment. This style promotes optimism and energy, aligning with lighter and more motivating messages.

- Nostalgic or melancholic music. Although less frequent, it is associated with intense negative emotions and feelings of suffering and vulnerability. Music of this type is probably used to evoke memories or to appeal to feelings of loss and sadness.

- Tense or dramatic music. It is prevalent in emotions of apprehension and apprehension, as well as in heightened negative emotions. This type of music is often used to intensify drama, fear, or the perception of urgency in the message.

3.2.4. Analysis of Engagement and Response Variables

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albertazzi, D., & Bonansinga, D. (2024). Beyond anger: The populist radical right on TikTok. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 32(3), 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, K. (2024). Tik Tok populism: A comparative analysis of left and right-wing populist sentiments on social media. Critique. A Worldwide Student Journal of Politics, 85–111. Available online: https://about.illinoisstate.edu/critique/fall-2024/.

- Ariza, A., March, V., & Torres, S. (2023). La Comunicación política de Javier Milei en TikTok. Intersecciones en Comunicación, 2(17). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badajoz-Dávila, D., Guerrero-Solé, F., & Mas-Manchón, L. (2023). #GobiernoCriminal! Framing the Spanish far right during the first COVID-19 wave. Methaodos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bast, J. (2021). Politicians, parties, and government representatives on instagram: A review of research approaches, usage patterns, and effects. Review of Communication Research, 9, 193–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdón-Prieto, P., Herrero-Izquierdo, J., & Reguero-Sanz, I. (2023). Political polarization and politainment: Methodology for analyzing crypto hate speech on TikTok. Profesional de la Información, 32(6), e320601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boréus, K. (2022). Migrants & natives—‘Them’ and ‘Us’: Mainstream and radical right political rhetoric in Europe. SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brader, T. (2005). Striking a responsive chord: How political ads motivate and persuade voters by appealing to emotions. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejo, J. (2010). “Análisis sociológico del sistema de discursos” de fernando conde gutiérrez del álamo empiria. Revista de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales, 20, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Carothers, T., & Lee, J. (2024, December 16). Election-related protests surged in 2024. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/emissary/2024/12/election-antigovernment-gaza-global-protest-tracker-2024?lang=en (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Casero-Ripollés, A. (2018). Research on political information and social media: Key points and challenges for the future. Profesional de la Información, 27(5), 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli Gattinara, P., Froio, C., & Pirro, A. L. P. (2022). Far-right protest mobilisation in Europe: Grievances, opportunities and resources. European Journal of Political Research, 61(4), 1019–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Martínez, A., & Díaz Morilla, P. (2021). La comunicación política de la derecha radical en redes sociales. De Instagram a TikTok y Gab, la estrategia digital de Vox. Dígitos: Revista de Comunicación Digital, 7, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, L., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2021). What are political parties doing on TikTok? The Spanish case. Profesional de la Información, 30(4), e300403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, L., Tejedor, S., & Blesa, F. (2023). TikTok and political communication: The latest frontier of politainment? A case study. Media and Communication, 11(2), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charaudeau, P., & Gentile, A. (2009). Reflexiones para el análisis del discurso populista. Discurso & Sociedad, 3(2), 253–279. [Google Scholar]

- Church, L. (2022). TikTok’s impact on political identity among young adults in the United States [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon]. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, A. J., & Atkinson, P. A. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, C. (2023). The World in 2024: Ten issues that will shape the international agenda. CIDOB Notes Internacionals, 299, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colussi, J., García-Estévez, N., & Ballesteros-Aguayo, L. (2024). Polarización y odio contra la ley trans de españa en TikTok. Revista ICONO 14. Revista científica De Comunicación Y Tecnologías Emergentes, 22(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchia, L. (2019). Political communication in Social Networks Election campaigns and digital data analysis: A bibliographic review. Rivista Trimestrale di Scienza dell’Amministrazione, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. O. (2009). La utilización de internet por parte de Barack Obama transforma la comunicación política. Quaderns del CAC, 33, 35–41. Available online: https://www.cac.cat/sites/default/files/2019-04/Q33_Costa_ES.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Crespo-Martínez, I., Garrido-Rubia, A., & Rojo-Martínez, J. M. (2022). El uso de las emociones en la comunicación político-electoral. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 58, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, R., Méndez-Muros, S., Pérez-Curiel, C., & Hinojosa-Becerra, M. (2023). Political polarization and emotion rhetoric in the US presidential transition: A comparative study of Trump and Biden on Twitter and the post-election impact on the public. Profesional de la Información, 32(6), e320606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, Y. (2020). Diversity in Europe: From pluralism to populism? In J. Vidmar (Ed.), European populism and human rights (pp. 52–71). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel, M., & Schiller, M. (Eds.). (2025). Popular music and the rise of populism in Europe. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6(3), 169–200. Available online: https://acortartu.link/e5idh (accessed on 17 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Estellés, M., & Castellví, J. (2020). The educational implications of populism, emotions and digital hate speech: A dialogue with scholars from Canada, Chile, Spain, the UK, and the US. Sustainability, 12(15), 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. (2024a). Eurobarometer. EU Post-electoral survey 2024. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3292 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- European Union. (2024b). Eurobarometer. Youth and democracy. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3181 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Eurostat. (2024a, August 2). Persons eligible to vote in the 2024 European Parliament elections by category of voters—Dedicated data collection. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_popep/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Eurostat. (2024b). Young people—Digital word. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Young_people_-_digital_world (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Ferrater Mora, J. (1990). Diccionario de filosofía. Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (2004). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa. Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, D., & Charte, M. (2024, May 23). La extrema derecha en la Unión Europea: De minoritaria e irrelevante a omnipresente y decisiva. RTVE. Available online: https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20240523/extrema-derecha-union-europea-minoritaria-irrelevante-a-omnipresente-decisiva/16112618.shtml (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Freistein, K., Gadinger, F., & Unrau, C. (2022). It just feels right. Visuality and emotion norms in right-wing populist storytelling. International Political Sociology, 16(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadamer, H. G. (2004). Verdad y Método I (6th ed.). Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H. G. (2015). Verdad y Método II (9th ed.). Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- García-Estévez, N., Cartes Barroso, M. J., & Méndez-Muros, S. (2025). Codebook for analyzing emotional communication strategies of far-right parties on TikTok during the 2024 European elections. Zenodo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gekker, A. (2019). Playing with power: Casual politicking as a new frame for analysis. In G. René, S. Lammes, M. de Lange, J. Raessens, & I. de Vries (Eds.), The playful citizen: Civic engagement in a mediatized culture (pp. 387–419). Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, A. M. (2019). Los influencers políticos: Nuevos actores comunicativos de la estructura mediática actual [Final Degree Project, Universitat Jaume I]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10234/186115 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Gilbert, D. (2024, July 16). TikTok pushed young german voters toward far-right party. Wired. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/tiktok-german-voters-afd/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Gómez, M. V., Sahuquillo, M. R., & Ayuso, S. (2024, June 7). Quién, cuándo y cómo van a votar los europeos: Las claves sobre las elecciones más importantes de la historia de la UE. El País. Available online: https://elpais.com/internacional/elecciones-europeas/2024-06-07/quien-cuando-y-como-van-a-votar-los-europeos-las-claves-sobre-las-elecciones-mas-importantes-de-la-historia-de-la-ue.html (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- González-Aguilar, J., Segado-Boj, F., & Makhortykh, M. (2023). Populist right parties on TikTok: Spectacularization, personalization, and hate speech. Media and Communication, 11(2), 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujard, C., Braun, E., & Scott, M. (2024, March 17). Europe’s far right uses TikTok to win youth vote. Politico. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/tiktok-far-right-european-parliament-politics-europe/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Guerrero-Solé, F., Mas-Manchón, L., & Virós i Martín, C. (2023). Populismo de extrema derecha y redes sociales. ¿El futuro de la democracia en juego? Universitat Pompeu Fabra Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Solé, F., Suárez-Gonzalo, S., Rovira, C., & Codina, L. (2020). Social media, context collapse and the future of data-driven populism. Profesional de la Información, 29(5), e290506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems. Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, G. J. (2019). The roles of social media in 21st century populisms: US presidential campaigns. Teknokultura: Revista de Cultura Digital y Movimientos Sociales, 16(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindarto, I. H. (2022). Tiktok and political communication of youth: A systematic review. Jurnal Review Politik, 12(2), 146–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohner, J., Kakavand, A. E., & Rothut, S. (2024). Analyzing radical visuals at scale: How far-right groups mobilize on TikTok. Journal of Digital Social Research, 6(1), 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaldi, G. (2024, June 10). EU elections: Far-right parties surge, but less than had been expected. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/eu-elections-far-right-parties-surge-but-less-than-had-been-expected-232018 (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Kakavand, A. E. (2024). Far-right social media communication in the light of technology affordances: A systematic literature review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 48(1), 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissas, A. (2024). Populist everyday politics in the (mediatized) age of social media: The case of Instagram celebrity advocacy. New Media & Society, 26(5), 2766–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lipschultz, J. H. (2022). Social media and political communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Literat, I., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2023). TikTok as a key platform for youth political expression: Reflecting on the opportunities and stakes involved. Social Media+Society, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malet, G. (2025). The activation of nationalist attitudes: How voters respond to far-right parties’ campaigns. Journal of European Public Policy, 32(1), 184–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manucci, L. (2021). Forty years of populism in the European Parliament. População e Sociedade, 35, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fresneda, H., & Zazo-Correa, L. (2024). Estudio de los perfiles en TikTok de El Mundo, El País, ac2alityespanol y La Wikly para analizar las oportunidades informativas de esta red social para la audiencia joven [Study of the profiles on TikTok of El Mundo, El País, ac2alityespanol and La Wikly to analyze the informative opportunities of this social network for the young audience]. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 82, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Serrano, J. C., Papakyriakopoulos, O., & Hegelich, S. (2020). Dancing to the partisan beat: A first analysis of political communication on TikTok. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM conference on Web Science (WebSci ‘20) (pp. 257–266). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Muros, S. (2021). Aproximación a una metodología de análisis de las emociones en el discurso político televisado. New Trends in Qualitative Research, 9, 372–383. [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, K. W., & Rice, L. L. (2024). TikTok and civic activity among young adults. Social Science Computer Review, 42(2), 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, A. (2023). The use of TikTok for political campaigning in Canada: The case of Jagmeet Singh. Social Media+Society, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondon, A., & Winter, A. (2020). Reactionary democracy: How racism and the populist far right became mainstream. Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Morejón-Llamas, N. (2023). Política española en TikTok. Del aterrizaje a la consolidación de la estrategia comunicativa. Prisma Social: Revista de Investigación Social, 40, 238–261. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Moreno, S., & Rojo Martínez, J. M. (2021). La construcción del enemigo en los discursos de la derecha radical europea: Un análisis comparativo. Encrucijadas: Revista crítica de Ciencias Sociales, 21(2), a2112. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/encrucijadas/article/view/88217 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Moret-Soler, D., Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2022). La negatividad digital como estrategia de campaña en las elecciones de la Comunidad de Madrid de 2021 en Twitter. Revista Prisma Social, 39(48), 73. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/4860 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Morozova, A., & Šlerka, J. (2024, July 3). How the far-right used TikTok to spread lies and conspirances. Vsquare. Available online: https://vsquare.org/far-right-tiktok-lies-conspiracies/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Mudde, C. (2019). The far right today. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, C. (2024a). The 2024 European elections: The far right at the polls. Journal of Democracy, 35(4), 121–134. Available online: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/the-2024-eu-elections-the-far-right-at-the-polls/ (accessed on 20 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C. (2024b). The far right and the 2024 European elections. Intereconomics, 59(2), 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C., Salmela, M., & von Scheve, C. (2021). From specific worries to generalized anger: The emotional dynamics of right-wing political populism. In M. Oswald (Ed.), Palgrave handbook of populism (pp. 145–160). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Fernández, E., & Rodríguez Hernández, J. (2021). Estrategia de comunicación de los cuerpos de seguridad a través de píldoras audiovisuales en TikTok. Policía Nacional y Guardia Civil en España. Revista Internacional de Investigación en Comunicación, 25(25), 160–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirro, A. L. P. (2023). Far right: The Significance of an umbrella concept. Nations and Nationalism, 29(1), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, É. (2022). Canada first is inevitable: Analyzing youth-oriented far-right propaganda on TikTok [Doctoral dissertation, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa]. [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo-Catalán, M., & Hornillo Gómez, I. (2010). Perspectiva emocional en la construcción de la identidad en contextos educativos: Discursos y conflictos emocionales. Revista de Educación, 353, 235–263. Available online: https://www.educacionfpydeportes.gob.es/revista-de-educacion/numeros-revista-educacion/numeros-anteriores/2010/re353/re353-09.html (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Rivera López, D., Riquelme Csori, F., Vernier, M., Balboa, A., Berríos, A., Rivera, V. V., Núñez, A., & Vivar, M. A. (2024). Funcionamiento discursivo de la extrema derecha chilena en prensa y TikTok. Revisionismo histórico a 50 años del Golpe de Estado. Letras (Lima), 95(141), 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-San-Miguel, A., Olivares-García, F. J., & Cartes-Barroso, M. J. (2021). Redes sociales como herramienta de comunicación política. In Periodismo y Comunicación Institucional (pp. 185–201). Fragua. [Google Scholar]

- Rooduijn, M., Pirro, A., Halikiopoulou, D., Froio, C., van Kessel, S., de Lange, S., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2023). The PopuList 3.0: An overview of populist, far-left and far-right parties in Europe. Available online: www.popu-list.org (accessed on 2 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sangiao, S. (2024). Cuarenta partidos de extrema derecha ocuparán uno de cada cuatro escaños en el nuevo Parlamento Europeo. Público. Available online: https://www.publico.es/internacional/cuarenta-partidos-extrema-derecha-ocuparan-cada-cuatro-escanos-nuevo-parlamento-europeo.html (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Sautera, D. A., Eisner, F., Ekman, P., & Scott, S. K. (2010). Cross-cultural recognitionof basic emotions through nonverbal emotional vocalizations. Proceedings of the NationalAcademy of Sciences, 107(6), 2408–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayago, S. (2014). El análisis del discurso como técnica de investigación cualitativa y cuantitativa en las ciencias sociales. Cinta de Moebio, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Señorán López, D. (2024, June 7). Mapa del auge de la derecha radical en la Unión Europea. Descifrando la Guerra. Available online: https://www.descifrandolaguerra.es/derecha-radical-union-europea/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Seppälä, M. (2022). Creative political participation on TikTok during the 2020 US presidential election. WiderScreen, 25(3–4). Available online: https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/3-4-2022-widerscreen-26-3-4/creative-political-participation-on-tiktok-during-the-2020-u-s-presidential-election/ (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Spanish Central Electoral Board. (2024). Elecciones al Parlamento Europeo 09 de junio de 2024. Calendario Electoral. Available online: https://www.juntaelectoralcentral.es/cs/jec/documentos/Calendario%20PE%2009-06-2024.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Stieglitz, S., & Dang-Xuan, L. (2013). Social media and political communication: A social media analytics framework. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 3, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subekti, D., Mutiarin, D., & Nurmandi, A. (2023). Political communication in social media: A bibliometrics analysis. Studies in Media and Communication, 11(6), 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweney, M. (2023, February 23). European Commision bans staff using TikTok on work devices over security fears. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/feb/23/european-commission-bans-staff-from-using-tiktok-on-work-devices (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Szabó, G. (2020). Emotional communication and participation in politics. Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics, 6(2), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerbiak, A., & Taggart, P. (2024). Euroscepticism and anti-establishment parties in Europe. Journal of European Integration, 46(8), 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J. A., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulos, P., Marcus, G. E., Valentino, N. A., & Foucault, M. (2019). Fear, anger, and voting for the far right: Evidence from the November 13, 2015 Paris terror attacks. Political Psychology, 40(4), 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinocur, N., & Goury-Laffont, V. (2024, June 17). Europe’s ‘foreigners out!’ generation: Why young people vote far right. Politico. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/far-right-europe-young-voters-election-2024-foreigners-out-generation-france-germany/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- We Are Social. (2024). Global digital report 2024. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/es/blog/2024/01/digital-2024-5-billiones-de-usuarios-en-social-media/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Wimmer, R. D., & Dominick, J. R. (1996). La investigación científica de los medios de comunicación: Una introducción a sus métodos. Bosh. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Medina, R., Suminas, A., & Fahmy, S. (2023). Securing the youth vote: A comparative analysis of digital persuasion on Tiktok among political actors. Media and Communication, 11(2), 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Political Party | Leader’s Name | Number of Videos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs—FPO | Herbert Kickl | 9 |

| Belgium | Vlaams Belang—VB | Tom Van Grieken | 62 |

| Bulgaria | Bъзpaждaнe | Kostadin Kostadinov | 4 |

| Croatia | Domovinski pokret—DP | Ivan Penava | 0 |

| Czech Republic | Svoboda a přímá demokracie—SPD | Tomio Okamura | 56 |

| Denmark | Dansk Folkeparti—DF | Morten Messerschmidt | 1 |

| Finland | Perussuomalaiset/Sannfinländarna—PS | Riikka Purra | 0 |

| France | Rassemblement national—RN | Marine Le Pen | 21 |

| France | Reconquête—REC | Éric Zemmour | 8 |

| Germany | Alternative für Deutschland—AfD | Tino Chrupalla | 11 |

| Germany | Alternative für Deutschland—AfD | Alice Weidel | |

| Greece | Dimokratikó Patriotikó Kínima—NIKI | Dimitris Natsios | 10 |

| Greece | Ellinikí Lýsi—EL/EΛ | Kyriakos Velopoulos | 46 |

| Greece | Foni Logikis | Afroditi Latinopoulou | 4 |

| Hungary | Fidesz-Magyar Polgári Szövetség—KDNP | Viktor Orbán | 24 |

| Hungary | Mi Hazánk | László Toroczkai | 21 |

| Italy | Fratelli d’Italia—FdI | Georgia Meloni | 21 |

| Italy | Lega Salvini Premier | Matteo Salvini | 46 |

| Poland | Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość | Slawomir Mentzen | 2 |

| Portugal | CHEGA—CH | André Ventura | 31 |

| Romania | Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor—AUR | George Simion | 31 |

| Romania | SOS România—SOS | Diana Sosoaca | 10 |

| Slovakia | Republika | Milan Uhrík | 35 |

| Slovenia | Nova Slovenija–Krščanski demokrati—N.Si | Matej Tonin | 0 |

| Slovenia | Slovenska demokratska stranka—SDS | Janez Janša | 1 |

| Spain | VOX | Santiago Abascal | 18 |

| Sweden | Sverigedemokraterna—SD | Jimmie Åkesson | 0 |

| TOTAL | 472 | ||

| Code | Theme | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cultural and national identity | 14 | 2.97 |

| 2 | Security and immigration | 53 | 11.23 |

| 3 | Criticism of the political system and/or other parties | 73 | 15.47 |

| 4 | Promises for the youth | 5 | 1.06 |

| 5 | Rejection of progressive social movements | 8 | 1.69 |

| 6 | Appeal to traditional values | 18 | 3.81 |

| 7 | Narrative of crisis or decline | 19 | 4.03 |

| 8 | Euroscepticism and anti-globalisation | 14 | 2.97 |

| 9 | Campaign actions, rallies and call to vote | 182 | 38.56 |

| 10 | Other | 86 | 18.22 |

| TOTAL | 472 | 100 | |

| Predominant Emotion | Frequency | % |

| Positive emotions of personal enjoyment | 57 | 12.08 |

| Emotions of empathy and social connection | 65 | 13.77 |

| Pride and ambition | 80 | 16.95 |

| Emotions of danger and insecurity | 73 | 15.47 |

| Intense negative emotions | 74 | 15.68 |

| Emotions of displeasure | 49 | 10.38 |

| Hope and illusion | 51 | 10.81 |

| Emotions of suffering and vulnerability | 15 | 3.18 |

| Other | 8 | 1.69 |

| Polarisation | Frequency | % |

| Positive | 214 | 45.34 |

| Negative | 208 | 44.07 |

| Neutral | 50 | 10.59 |

| Strategic orientation of emotion | Frequency | % |

| Positive ones related to personal well-being | 88 | 18.64 |

| Positive social connection and hope | 119 | 25.21 |

| Negative statements related to danger or insecurity | 107 | 22.67 |

| Negative feelings related to anger or suffering | 93 | 19.70 |

| Neutral with positive trend | 37 | 7.84 |

| Neutral with negative trend | 28 | 5.93 |

| TOTAL | 275 | 100 |

| Intensity Low | Intensity Medium | Intensity High | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative polarisation | 57 | 104 | 53 |

| Positive polarisation | 6 | 116 | 86 |

| Neutral | 16 | 30 | 4 |

| Predominant Emotion/Music | Absence of Music | Neutral or Ambient | Epic | Cheerful or Lively | Nostalgic or Melancholic | Tense or Dramatic | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive emotions of personal enjoyment | 11 | 12 | 2 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 57 |

| Emotions of empathy and social connection | 17 | 9 | 6 | 24 | 4 | 5 | 65 |

| Pride and ambition | 40 | 14 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 80 |

| Emotions of danger and insecurity | 48 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 73 |

| Intense negative emotions | 52 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 74 |

| Emotions of displeasure | 41 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 49 |

| Hope and illusion | 20 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 51 |

| Emotions of suffering and vulnerability | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15 |

| Other | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| TOTAL | 247 | 67 | 38 | 76 | 14 | 30 | 472 |

| National Symbols | Party Symbols | Other Symbols | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | 407 (86.23%) | 248 (52.54%) | 436 (92.37%) |

| Present in the background | 45 (9.53%) | 180 (38.14%) | 36 (7.63%) |

| Prominent | 20 (4.24%) | 43 (9.11%) | 0 |

| Variable | Average | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likes | 15.991 | 47.210 | 2 | 522.100 |

| Comments | 827 | 2.710 | 1 | 27.100 |

| Shared/Favourites | 963.8 | 3.492 | 0 | 74.500 |

| Main Topics | Normalised Likes (%) |

|---|---|

| Rejection of progressive social movements | 9.69 |

| Appeal to traditional values | 4.27 |

| Cultural and national identity | 4.02 |

| Campaign actions, rallies, and calls to vote | 3.99 |

| Other | 3.92 |

| Security and immigration | 3.12 |

| Criticism of the political system and/or other parties | 3.03 |

| Euroscepticism and anti-globalisation | 2.41 |

| Promises for youth | 2.26 |

| Narrative of crisis or decline | 1.86 |

| Predominant Emotion | Normalised Likes (%) |

|---|---|

| Positive emotions of personal enjoyment | 5.88 |

| Emotions of suffering and vulnerability | 4.99 |

| Hope and illusion | 4.98 |

| Emotions of danger and insecurity | 4.01 |

| Emotions of displeasure | 3.96 |

| Emotions of empathy and social connection | 3.31 |

| Pride and ambition | 2.78 |

| Others | 1.88 |

| Intense negative emotions | 1.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cartes-Barroso, M.J.; García-Estévez, N.; Méndez-Muros, S. Attracting the Vote on TikTok: Far-Right Parties’ Emotional Communication Strategies in the 2024 European Elections. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010033

Cartes-Barroso MJ, García-Estévez N, Méndez-Muros S. Attracting the Vote on TikTok: Far-Right Parties’ Emotional Communication Strategies in the 2024 European Elections. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleCartes-Barroso, Manuel J., Noelia García-Estévez, and Sandra Méndez-Muros. 2025. "Attracting the Vote on TikTok: Far-Right Parties’ Emotional Communication Strategies in the 2024 European Elections" Journalism and Media 6, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010033

APA StyleCartes-Barroso, M. J., García-Estévez, N., & Méndez-Muros, S. (2025). Attracting the Vote on TikTok: Far-Right Parties’ Emotional Communication Strategies in the 2024 European Elections. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010033