1. Introduction

Since its foundation in 1923 (

Robb 2014), the Walt Disney company has created stories, characters, and experiences that have had an undeniable impact on several generations of spectators. Their movies led to the creation of new worlds that became real on their theme parks and Disney stores (

Real 1977). As the precursors of animation as a film genre, this creation relied mainly on the quest for realism in animation techniques through the telling of fairytale narratives (

Pallant 2010) based on what Campbell defined as the “nuclear unit of monomyth”, in which a hero “ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered, and a decisive victory is won” (

Campbell 1993); basically, stories revolving around the strength of a single character. Moreover, Disney opted to follow a formalist approach in the animation of its movies in order to later establish the principles of animation, in which the story lost its significance over the technique and the aesthetics (

Thomas and Johnston 1981). The early 90s witnessed a relevant change in such an approach. That decade, a period referred to as Disney’s renaissance, led to the levels of “aesthetic and industrial growth” (

Pallant 2011, p. 89) that were, in many ways, unprecedented. That same decade, though, saw the emergence of Pixar, whose release of

Toy Story in 1995 took animation to levels of significance that had not even been considered by many up until then. “Pixar soon became the number one trusted brand for family entertainment, a title once held by Disney”, explains

Haswell (

2019, p. 92), recalling that by 2005 “Disney’s own market research confirmed that mothers with children under the age of 12 generally rated Pixar’s brand higher than Disney’s”. One year later, Disney “sought to revive its animation capabilities” by announcing the acquisition of Pixar, by then already “one of the most successful moviemakers in Hollywood” (

DePamphilis 2009, p. 149).

One of the reasons for both the shift in audience’s preferences and Disney’s purchase itself could be Pixar’s decided emphasis on their storytelling, defending the story through the persistence of humanity through the story and characters. This approach constitutes an aesthetic storytelling style and a presentation of worlds with rules to be discovered by both characters and audiences (

Herhuth 2017). Furthermore, for the creation of their characters and their environment, Pixar opts to dive its creators into the culture or world they want to show: for the production of the feature

Brave, the creative team took archery classes in Scotland, and for the production of the feature

Ratatouille, the creators were sent to a Michelin star-winning restaurant in France to learn the “art of making ratatouille” (

Catmull 2014).

But probably the key to Pixar’s culture is the Braintrust: a mechanism—based on honesty and candor—created during the production of

Toy Story 2 that lets every worker speak freely about the productions going on at that moment (

Wise 2014). As Ed Catmull describes it himself: “put smart, passionate people in a room together, charge them with identifying and solving problems, and encourage them to be candid with one another”. Directors feel personally attached to their movies and their characters, and consequently, they may not be able to see the reality they face. The Braintrust became a tool to solve this problem, always making clear that the director was never attacked but positively criticized to improve his film. This mechanism was adopted by Disney with the purchase of Pixar in 2006 (

Catmull 2014), which starts to demonstrate certain influence. As

Haswell (

2019, p. 97) puts it, “during the months following the acquisition, Catmull and Lasseter established the Disney Story Trust. Based on the model of Pixar’s Braintrust, the meetings allow the opportunity to discuss, troubleshoot, and screen sequences from current projects”. Pixar’s Braintrust cross-refers to Disney’s Sweatbox (

Friedman 2022), which the studio had already implemented decades before: “the origin of the term sweatbox is said to date back to when Walt Disney would view the scenes completed through rough animation with his animators and critique their work”, something “comparable to ‘rushes’ in the realm of live action production” (

Winder and Dowlatabadi 2011, p. 240). This makes it an even more interesting twist: rather than importing techniques from Pixar that were unknown for Disney, it can be said that Pixar revitalized and brought a breath of fresh air that reminded the company that led animation for so many years of some of the keys to their previous success.

Pixar’s impact on Disney was visible at several levels, as

Haswell (

2019, p. 100) proposes discussing the so-called “princess curse”, central to the storytelling of the group, which both Disney and Pixar tried to shoo away, opting “for more gender-neutral adjectives for the titles of the fairy tale films” in titles like

Tangled or

Brave, following the criticisms received after the release of

The Princess and the Frog.

Frozen, centered around two females and their sisterly relationship, chose, accordingly, to also “featuring the film’s male counterparts, Kristoff and Hans, as well as its sidekicks, the reindeer, Sven, and Olaf the talking snowman” (

Haswell 2019, p. 102) in their particular retake of the traditional princess storyline—to a large extent a full rebirth of the classical princess narrative. “Pixar”, adds

Wills (

2017, p. 20), “introduced more complexity in (Disney’s) stories”.

Movshovitz’s analysis of Pixar’s success mostly revolves around narratological tools, some of them coincidental with some elements previously suggested by other authors in the introduction, though the author also reflects on how the studio’s storytelling machinery takes us, inexcusably, to the deeper level of forcing “characters to go through an emotional journey. An uncomfortable character is compelled to work hard to get back to its comfort zone, just like we would in real life. This desire propels actions, decisions and emotions”

Movshovitz (

2015, p. 7).

Beaumont and Larson (

2021, p. 76) agree on the importance of both the emotional factor and the journey, underscoring though that “in an animated story the destination is just as essential as the steps that happen along the way (…) ultimately, the full change won’t come until they reach their destination”. In one of his many reflective works on animation,

Wells (

2007, p. 176) brings to the debate “a formula that has stuck” with him “over the years: complex characters in simple situations work much better than simple characters in complex situations”, and

Lupton (

2017, p. 24) adds in this respect that “complex narratives contain stories within stories and conflicts within conflicts”.

All these insights not only illuminate some of the keys of animation in general as well as success for both Disney and Pixar separately and jointly, they also hint towards a degree of film complexity that has arguably been brewing through different historical stages of animation prior to Disney’s purchase of Pixar and was taken even further after the acquisition. Thus, understanding film complexity becomes crucial to determining the axes around which an analysis of such a phenomenon can be implemented in the framework of some of the most relevant animation titles of the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st.

4. Results

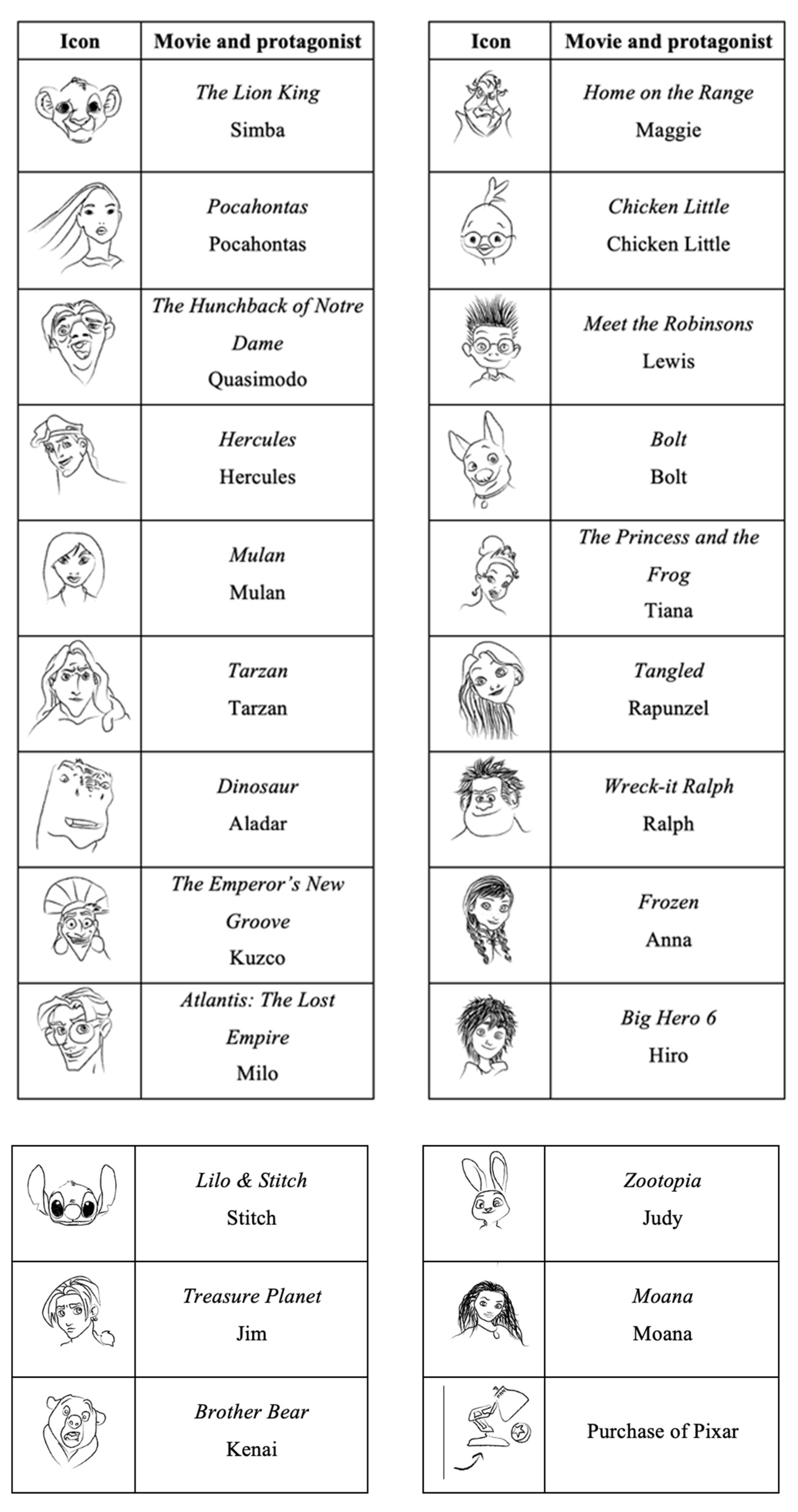

The results obtained have been articulated both through descriptive analysis and the visualization of the aforesaid results through graphics. For the elaboration of the graphics, we have created a series of icons that represent the different movies and their protagonists. The legend to these icons can be found in

Appendix A.

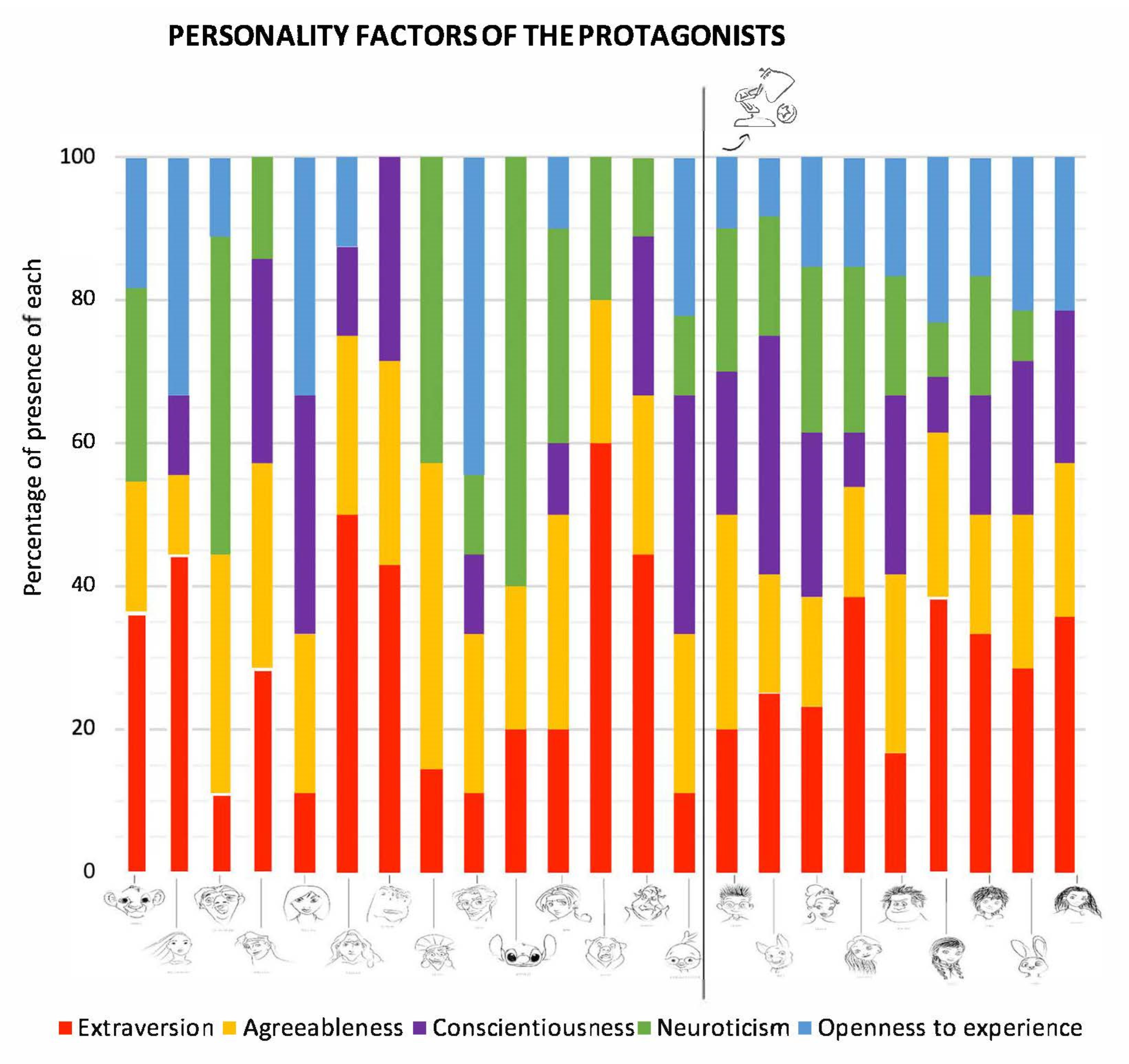

The results pertaining to the psychological construction of the protagonists are represented by two different bar graphs. On the one hand,

Figure 1 represents the total number of personality traits of each protagonist in every Disney animation feature included in the sample. On the other hand,

Figure 2 represents the proportion in which each personality factor is present in the psychological construction of each protagonist. In both graphs, the protagonists of each movie are ordered based on the year of release, from 1994 to 2018, and divided into features before the purchase of Pixar and features released after. Moreover, the five factors of personality have one color assigned to each: red for extraversion, yellow for agreeableness, purple for conscientiousness, green for neuroticism, and blue for openness to experience. The charts with the data used to elaborate these graphs can be found in

Appendix B and

Appendix C.

Before the purchase of Pixar, the average number of psychological traits is 8. The protagonist with most traits is Simba with 11, followed by Jim with 10, while the protagonists with fewer traits are Stitch and Kenai with 5, followed by Hercules, Milo, Maggie, and Chicken Little with 7. On the other hand, the average number of traits in the protagonists of the features released after the purchase is higher at 12. The second maximum number of traits amongst the movies released before the purchase is equal to the lowest number of traits amongst the movies released after, 10 traits in Lewis. The protagonists with most traits are Moana and Judy with 14, followed by Anna, Rapunzel, and Tiana with 13.

In relation to the protagonists in the features released before the purchase of Pixar, only 21.4% (Milo, Jim, and Chicken Little) have all the five personality factors, while 50% (7 out of 14) have four of them. From these seven characters, 42.86% lack the factor of neuroticism (Pocahontas, Mulan, and Tarzan), 28.57% lack the factor of conscientiousness (Simba and Quasimodo), and another 28.57% lack the factor of openness to experience (Hercules and Maggie). Last but not least, 28.6% (4 out of 14) have three of the personality factors. From these four characters, 75% lack both conscientiousness and openness to experience (Kuzco, Stitch, and Kenai), while 25% lack both neuroticism and openness to experience (Aladar). On the other hand, from the protagonists in the features released after the purchase of Pixar, 88.8% (8 out of 9) have all the five factors, while only Moana, representing 11.2%, has four of them, lacking the factor of neuroticism.

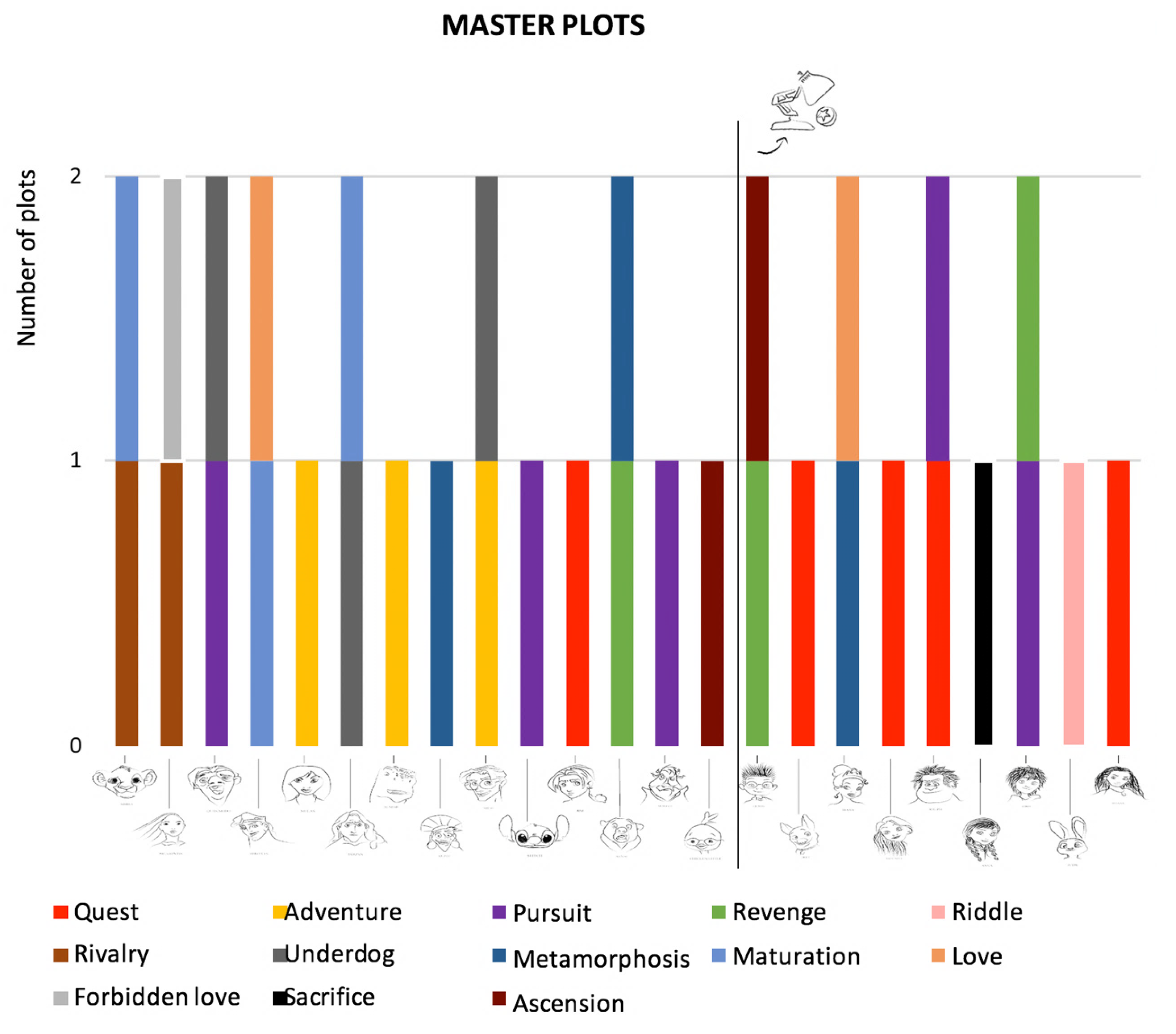

4.3. Master Plo

The numbers and variety of master plots in each Disney animation feature included in the sample are represented using a bar graph (

Figure 5). The movies are ordered based on their year of release, from 1994 to 2018, and divided into features before the purchase of Pixar and features released after. Each type of master plot is represented by a different color: red for quest, yellow for adventure, purple for pursuit, green for revenge, pink for riddle, brown for rivalry, dark grey for underdog, dark blue for metamorphosis, light blue for maturation, orange for love, light grey for forbidden love, black for sacrifice, and maroon for ascension. The chart with the data used to elaborate this graph can be found in

Appendix E.

Before the purchase of Pixar, 50% of the features have one master plot, and the other 50% has two master plots. On the other hand, 55.5% of the features released after the purchase have one master plot, and the other 44.5% has two of them.

The most common master plots in the features released before the purchase are maturation, pursuit, underdog, and adventure, present in a total of twelve features (three each), followed by rivalry and metamorphosis, which are present in a total of four features (two each). Finally, master plots quest, revenge, love, forbidden love, and ascension are present in five features.

On the other hand, the most common master plot in the features released after the purchase is quest, present in four different features, followed by master plots pursuit and revenge, which are present in a total of four features (two each). Finally, present in a total of five features, we find master plots riddle, metamorphosis, love, sacrifice, and ascension. Master plots rivalry, underdog, maturation, and forbidden love are not present in any feature after the purchase of Pixar, while riddle and sacrifice appear for the first time.

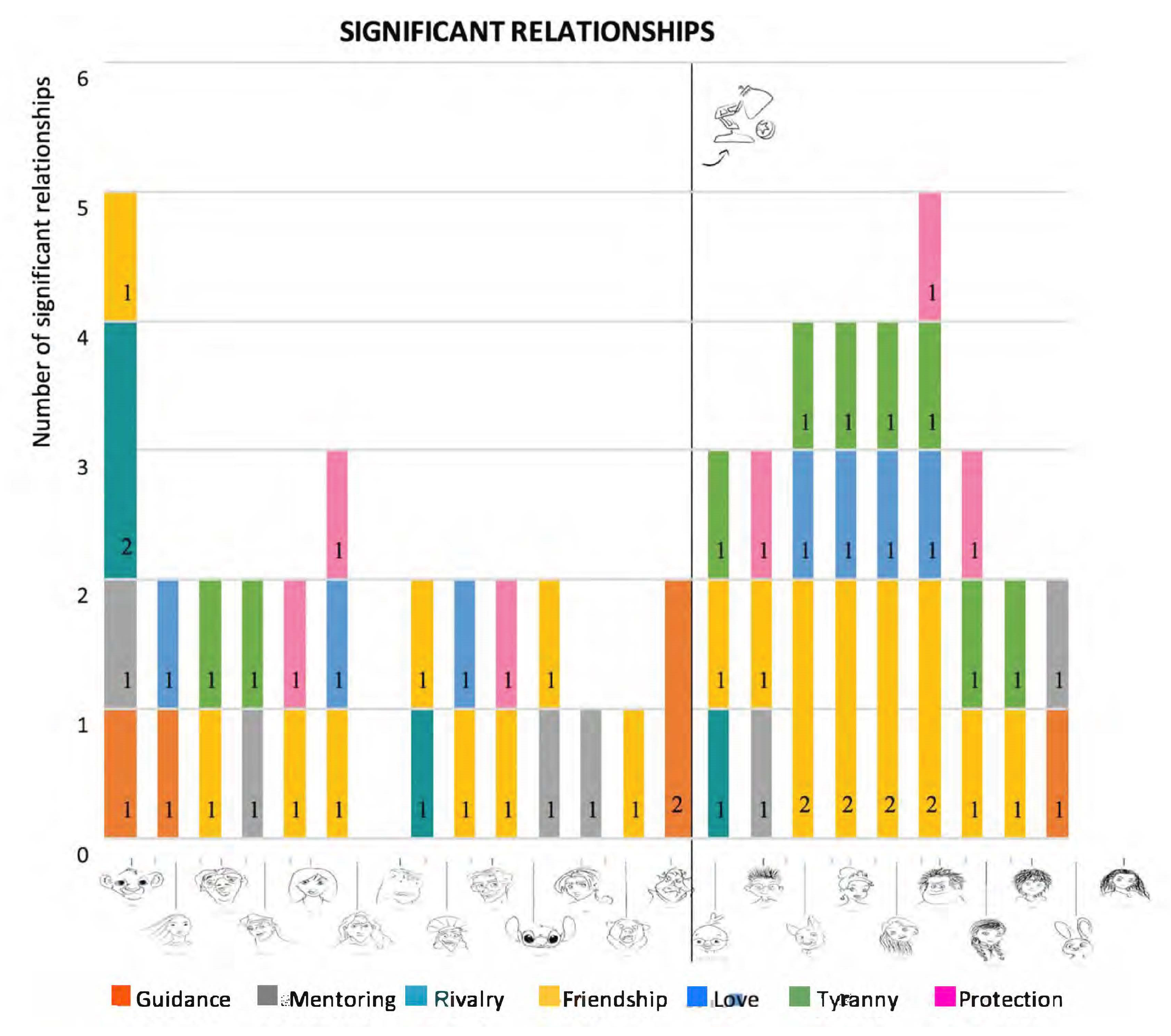

4.4. Significant Relationships between Characters

The numbers and variety of significant relationships between characters in each Disney animation feature included in the sample are represented using a bar graph (

Figure 6). The movies are ordered based on their year of release, from 1994 to 2018, and divided into features before the purchase of Pixar and features released after. Each type of relationship is represented by a different color: orange for guidance, grey for mentoring, emerald for rivalry, yellow for friendship, blue for love, green for tyranny, and pink for protection. The chart with the data used to elaborate this graph can be found in

Appendix F.

As the graphs show, the average number of significant relationships is two in the features released before the purchase and three in those released after. Every feature has significant relationships between the different characters except for Dinosaur, which does not have any. There are three features released before the purchase that have guidance relationships. The guidance goes from one character to the protagonist, who needs help to find the right path, with the exception of Chicken Little. In this feature, we find the first and only guidance relationship in which the guidance goes from the protagonist to another character. After the purchase, there is only one feature with a guidance relationship: Moana, and in this feature, she is the one to receive the guidance from her grandmother.

Mentoring relationships are present in four features before the purchase. These also go from one character to the protagonist, who needs help to realize certain aspects of life or the self. After the purchase, we find two features with mentoring relationships: Bolt and Moana. In the case of Bolt, it is the protagonist who receives the mentoring from another character but not in the case of Moana. In this feature, it is the protagonist who mentors another character about existential matters.

There are three features with rivalry relationships, two of them from before the purchase and one from after. The rivalry relationships between the characters of animation features released before the purchase are based on the yearning for power, while the one in Meet the Robinsons (released after the purchase) has a backstory that helps the audience understand the nature of the relationship and the origin of the rivalry.

Friendship relationships are the most common ones in the features released both before and after the purchase. The friendships between the characters of the features released before the purchase are based on helping each other truthfully and loyally whenever it is needed. On the other hand, the friendships between the protagonists and other characters of the features released after the purchase go through some kind of conflict that separates them, breaking the relationship for a short period of time. Anyway, the character ends up assisting the protagonist at the highest dramatic point.

There are seven features with love relationships: three from before the purchase and four after it. All of them bring the two involved characters some type of openness to new experiences, ideologies, or knowledge. Both characters stimulate each other and fall in love progressively and against the odds.

Relationships of tyranny appear in nine features; two of them were released before the purchase, and the other seven were released after. All the relationships before the release and the ones in Meet the Robinsons, The Princess and the Frog, and Tangled show their tyrants from the beginning, making it clear for the audience who is the “bad guy”. On the other hand, in the relationships in the last features (Wreck-it Ralph, Frozen, Big Hero 6, and Zootopia), the tyrants are masked as good and trustworthy people that help the protagonist in their task. The discoveries of the protagonist are what reveal the tyrants as who they really are.

Last but not least, we find six protection relationships between the characters of the features: three from the ones released before and three from the ones released after. These relationships are based on the protection from one to the other and in which the protagonists save the other characters from death or capture. The only exception is the relationship in Big Hero 6 between Hiro and Baymax, in which it is the protagonist who is to be saved by the other character; Hiro also reciprocally protects Baymax since the robot only knows the human world from a scientific perspective, which in itself endangers its survival.

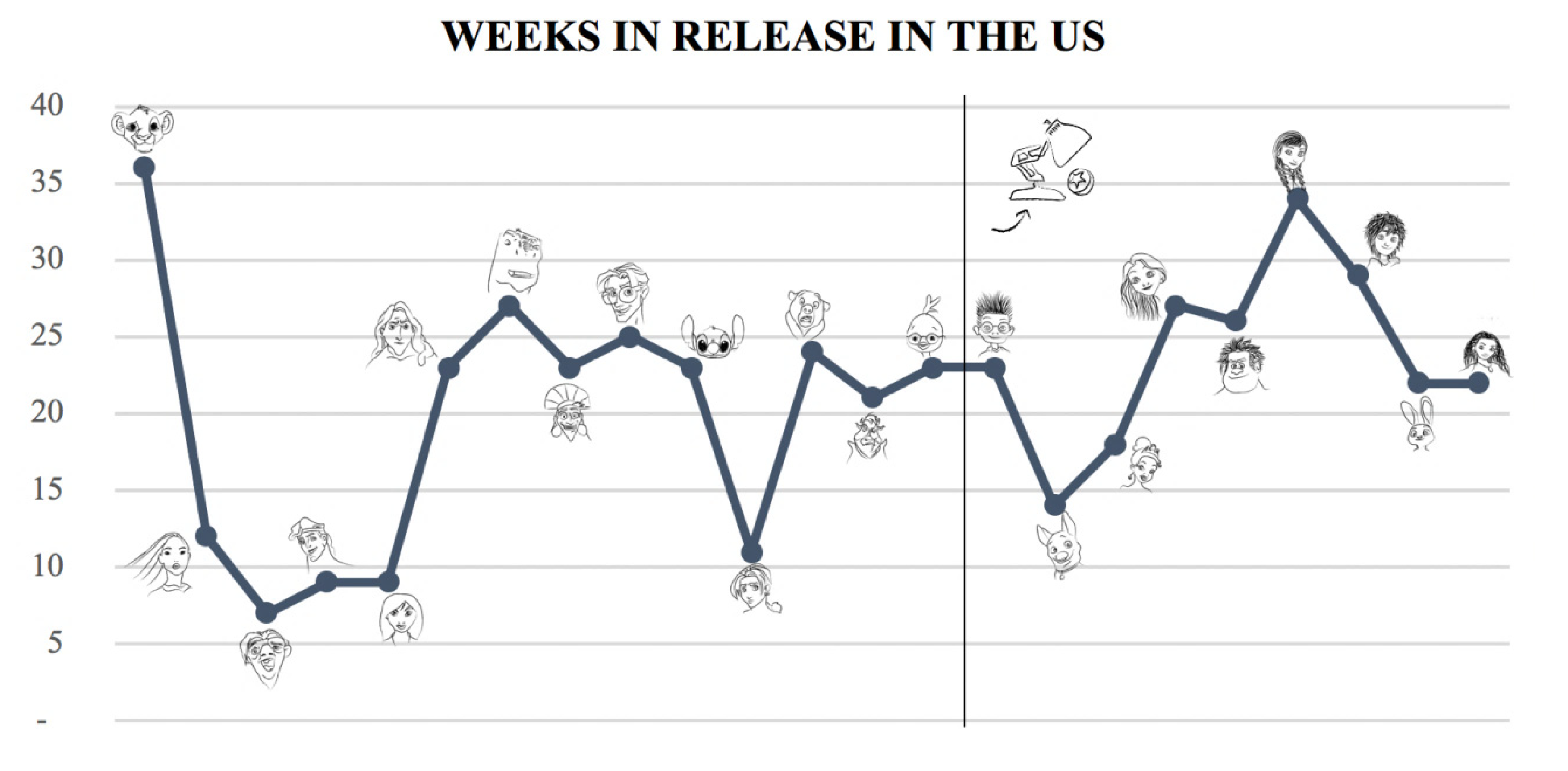

4.5. Box Office and Reviews from Critics

The results of the box office data are represented by two different line graphs. On the one hand,

Figure 7 represents the number of weeks each Disney animation feature included in the sample has been in release in the United States. On the other hand,

Figure 8 represents the worldwide total gross income of each Disney animation feature included in the sample. In both graphs, the movies are ordered based on their year of release, from 1994 to 2018, and divided into features before the purchase of Pixar and features released after. The charts with the data used to elaborate these graphs can be found in

Appendix G.

The weeks in release before the purchase start at their highest peak of 36 with The Lion King but decrease immediately to 12, 7, and 9 with Pocahontas, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hercules, and Mulan, respectively. From this point, they increase again, maintaining it around 20 until the purchase, with the exception of Treasure Planet, which decreases to 11. Right after the purchase of Pixar, the weeks in release drops to 14 with Bolt, but then starts increasing again, overcoming the average of the previously released movies, maintaining it around 30 weeks, and overcoming it with Frozen, but never reaching the highest peak of The Lion King. After 34 weeks of Frozen, the time decreased again to 29 and 22 weeks with Big Hero 6 and Zootopia, respectively.

The features with the highest number of weeks in release are The Lion King (36), Frozen (34) and Big Hero 6 (29). The first one belongs to the movies released before the purchase, while the two last ones belong to the ones after the purchase. The features with the lowest ones are The Hunchback of Notre Dame (7), Hercules, and Mulan (both 9). All of them belong to the movies released before the purchase.

The worldwide total gross income of the movies before the purchase (The Lion King to Chicken Little) follows a decreasing tendency, with its highest peak with The Lion King and its lowest with Brother Bear. After the purchase, the total gross income increases, never overcoming 500 million dollars, with The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Tarzan, Lilo & Stitch, and Chicken Little, but later decreases even more with Hercules, The Emperor’s New Groove, Treasure Planet, and Home on the Range.

Once Disney buys Pixar in 2006, the total gross income falls down with the first movie, Meet the Robinsons, reaching the lowest value since the purchase. It increases with Bolt and decreases again with The Princess and the Frog. Since then, the total gross income starts to follow an increasing tendency, reaching its highest peak in 2013 with Frozen. It also has some decreasing and low points with Wreck-it Ralph and Big Hero 6, but these are never lower than the second highest gross income from before the purchase, which is Tarzan with 448 million dollars.

The features with the highest worldwide total gross incomes are Frozen ($1,276,480,335), Zootopia ($1,023,784,195), and The Lion King ($968,483,777). The first two belong to the movies released after the purchase, while the latter belongs to the ones released before. The features with the lowest worldwide total gross incomes are Brother Bear ($85,336,277), Home on the Range ($103,951,461), and Treasure Planet ($109,578,115). All of them belong to the movies released before the purchase.

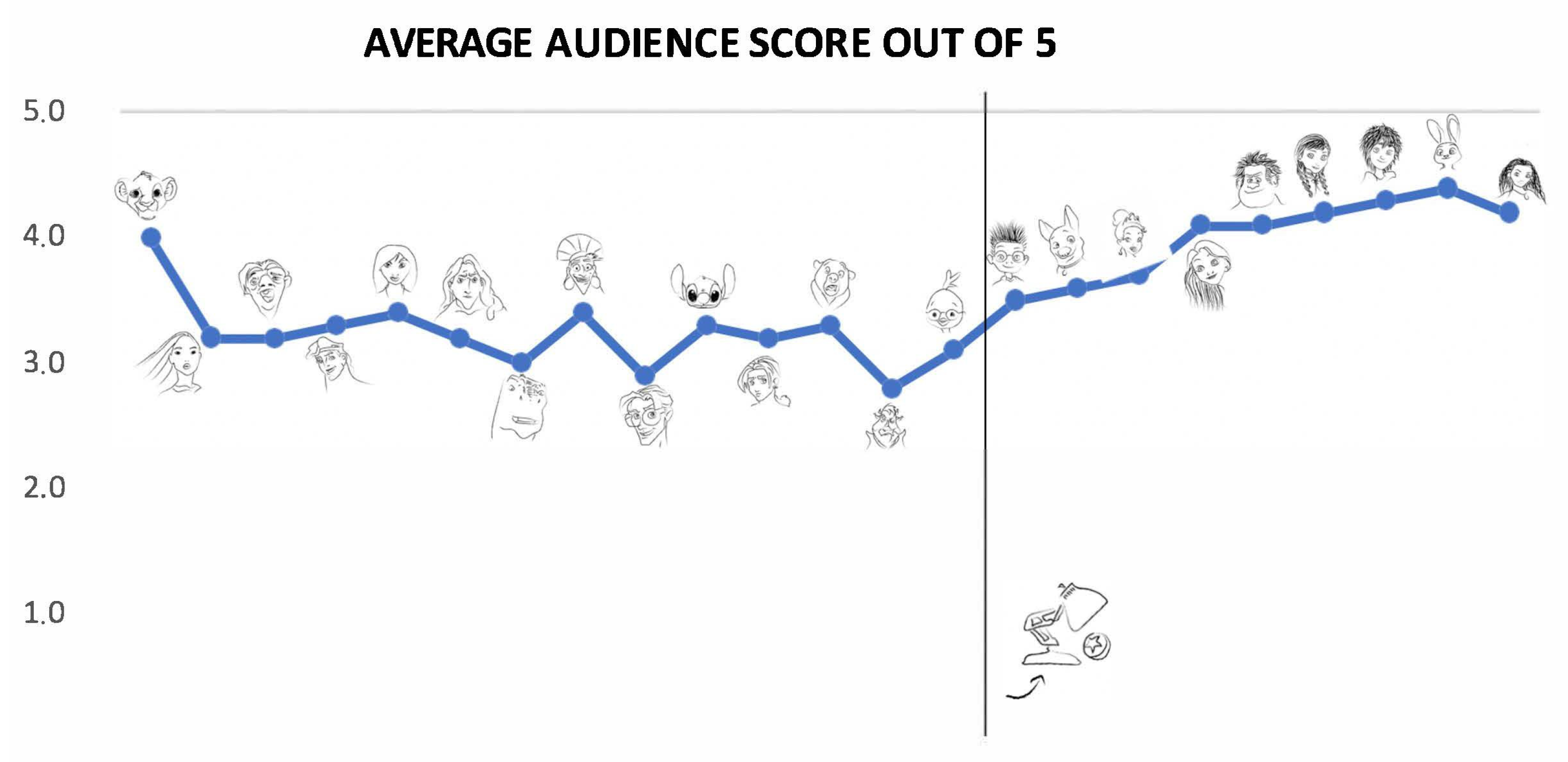

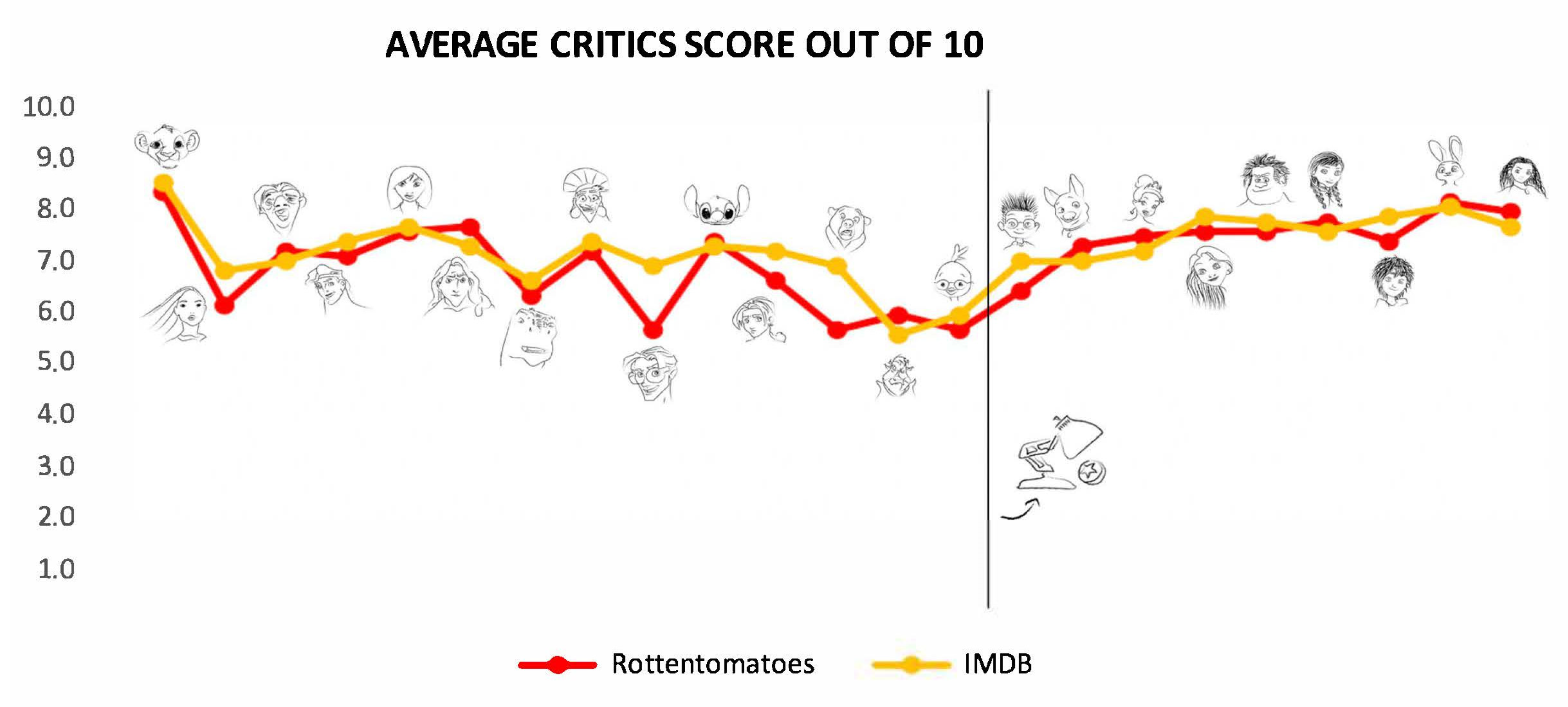

The ratings are also represented by three different line graphs. On the one hand,

Figure 9 represents the average audience score out of 5, given by the users of rottentomattoes.com to each Disney animation feature included in the sample. On the other hand,

Figure 10 represents the average critics score out of 10, given by the users of rottentomattoes.com and IMDB.com to each Disney animation feature included in the sample. Last but not least,

Figure 11 represents the percentage of audience and critics positive reviews each Disney animation feature has received by the users of rottentomatoes.com. In all the graphs, the movies are ordered based on their year of release, from 1994 to 2018, and divided into features before the purchase of Pixar and features released after.

The average score given by the audience to the features released before the purchase has a decreasing tendency, from its highest peak with The Lion King to its lowest with Home on the Range. It has some high increasing points in between with Mulan, The Emperor’s New Groove, Lilo & Stitch, and Brother Bear. Still, no feature apart from The Lion King receives an average score higher than 3.4. After the purchase, the average score starts to follow an increasing tendency, reaching its highest peak with Zootopia. These features do not receive a score lower than 3.5, which constitutes the lowest peak after the purchase with Meet the Robinsons.

The features with the highest average audience scores are Zootopia (4.4), Big Hero 6 (4.3), and The Lion King (4). The first two belong to the movies released after the purchase, while the latter belongs to the ones released before. On the other hand, the features with the lowest average audience scores are Home on the Range (2.8), Atlantis (2.9), and Dinosaur (3). All of them belong to the movies released before the purchase.

As a general rule, the users of IMDB and rottentomatoes give the features a similar score with a difference of less than 0.5 points, except for Pocahontas, Atlantis, Treasure Planet, and Brother Bear, in which the IMDB users rate higher than rottentomatoes’. Before the purchase, the average critics score of both webpages follows a decreasing tendency, with its highest peak with The Lion King and its lowest with Atlantis in the case of rottentomatoes and Home on the Range in IMDB. In between, there are also high points with Tarzan, The Emperor’s New Groove, and Lilo & Stitch, but also some other low ones with Pocahontas, Dinosaur, and Chicken Little. After the purchase, the average critics score follows an increasing trend from its lowest peak with Meet the Robinsons and its highest with Zootopia, which still does not overcome the score of The Lion King.

IMDB users give their higher scores to The Lion King (8.5), Zootopia (8), Tangled, and Big Hero 6 (both 7.8). The first feature belongs to the ones released before the purchase, while the three latter belong to the ones released after. The lower scores from IDMB are for Home on the Range (5.4), Chicken Little (5.8), and Dinosaur (6.5). All of them belong to the movies released before the purchase.

On the other hand, rottentomatoes users give their higher scores to The Lion King (8.3), Zootopia (8.1), and Moana (7.9). Again, the first feature belongs to the ones released before the purchase, while the two latter belong to the ones released after. The lower scores are for Chicken Little, Atlantis (both 5.5), Home on the Range (5.8), and Pocahontas (6). Again, all of them belong to the movies released before the purchase.

The percentage of positive reviews given by the critics of rottentomatoes before the purchase follows a decreasing trend from its highest peak with The Lion King to its lowest with Chicken Little, but it has, in between, many high points with Tarzan, The Emperor’s New Groove, and Lilo & Stitch and low ones with Pocahontas, Atlantis, and Brother Bear. After the purchase, the trend grows from its lowest peak with Meet the Robinsons to its highest with Zootopia.

On the other hand, the percentage of positive reviews given by the audience follows a similar decreasing tendency, with The Lion King as the highest peak and Home on the Range as its lowest one. It also has high points with The Emperor’s New Groove and Lilo & Stitch, but instead of Tarzan, the third highest point is for Mulan. The low points are the same as the critics’. After the purchase, the tendency also grows, but more subtly than the critics’.

The features with the highest percentages of positive reviews from the critics are Zootopia (98%), Moana (96%), and The Lion King (92%), while the ones with the lower percentages are Chicken Little (37%), Brother Bear (38%), and Home on the Range (54%). For the audience, the features with the highest percentage of positive reviews are The Lion King (93%), Zootopia (92%), and Big Hero 6 (91%), while the lowest ones are Chicken Little, Dinosaur (both 47%), Home on the Range (28%), and Atlantis (52%).

5. Conclusions

The present research is aimed at shedding light on the narratological evolution of Disney storytelling in a quarter of a century, divided by the acquisition of Pixar in January 2006. All the results should be interpreted, first, in the framework of an evolution of society itself, to which artists are naturally responsive. Disney’s renaissance in the 1990s was a result, amongst other phenomena, of the studio’s understanding of new audiences. Their creations after the purchase of Pixar were obviously influenced by Pixar’s innovations, but also by many other social changes that were occurring simultaneously. Our investigation has attempted to make a contribution to the exciting debate on the relationship between these two brands and its effect on their creativity. This has led to some ultimate reflections connected to the hypotheses that we formulated at the beginning of this research.

A close analysis of our results confirms that hypothesis 1 can be assumed to be verified: three of its sub-hypotheses are confirmed, another is partly confirmed, and only one (sub-hypothesis 4) is completely rejected. Hence, the Pixar effect changed the narrative and discourse of Disney’s features, enriching it through a more complete construction of protagonists and the relationships between the characters. The fact that these changes began to be noticeable in the features released after 2006 drives us to the conclusion that Pixar played a significant role in them.

The psychological construction of the protagonists of Disney animation features after the purchase of Pixar is more balanced and closer to human nature and behavior than those in features released before the purchase. The psychological profiles of the protagonists in the last nine features have a greater number of personality traits, which, at the same time, are distributed in a more balanced way across the different factors. This makes the protagonists more complete, reliable, and easy to feel identified with; less fantastic and more human. On the other hand, the protagonists in the features released before the purchase are more easily typecast in one of the factors. For example, Tarzan is extremely extrovert, Kuzco extremely non agreeable, Quasimodo extremely neurotic, Mulan or Chicken Little extremely conscientious and Milo extremely open. Therefore, sub-hypothesis 1 can be confirmed.

Moreover, the fact that Disney gives their protagonists more growth character arcs, apart from change, after the purchase of Disney drives us to the conclusion that the narrative construction of the protagonists changes in such a way that it represents life more accurately and encouragingly, creating fewer heroes and more people with the ability to learn and generate change in others. The protagonists in features before the purchase, or at least in the majority of them, have to become heroes in order to be recognized and accepted, as if the inner process of realization and learning did not matter as much as becoming a hero recognized by the community. So, have the character arcs deepened since the purchase? They have in their reflection on how to face and process self-development.

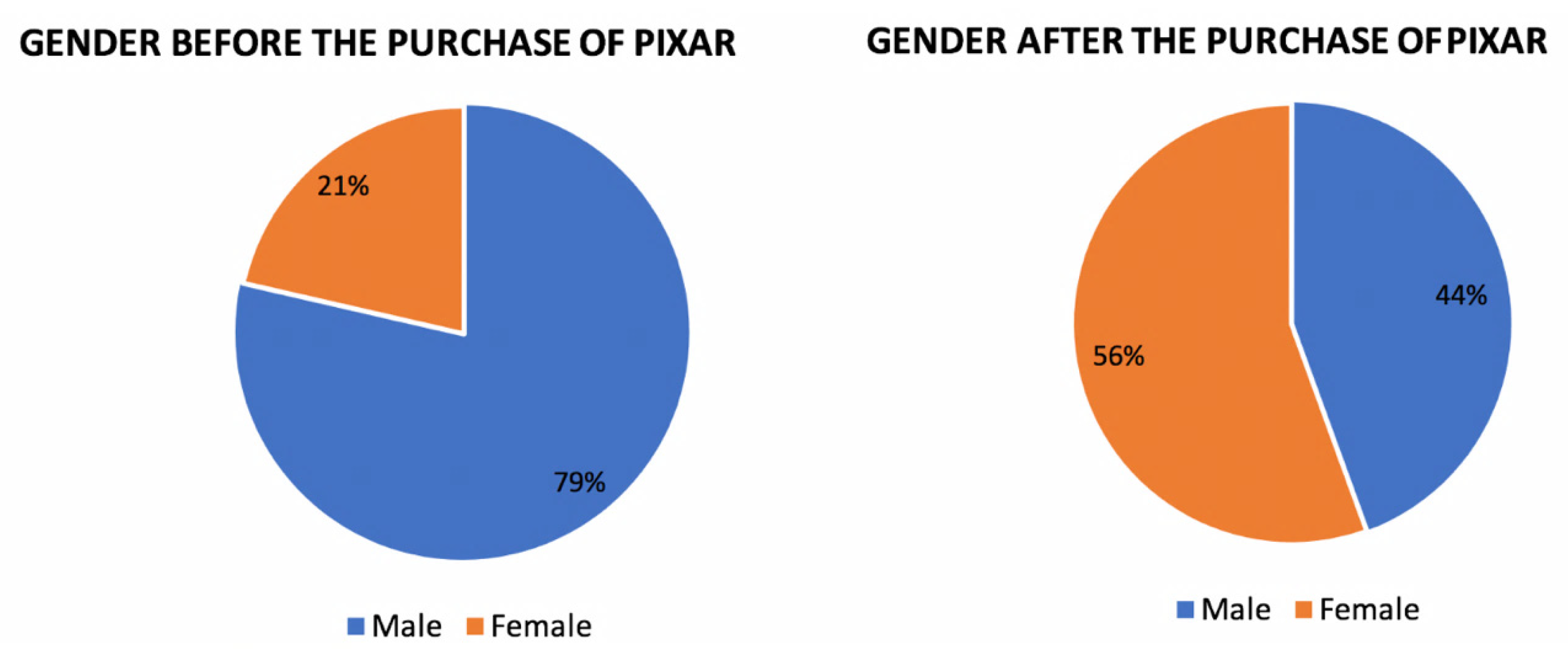

Next, we can also confirm sub-hypothesis 3 related to the variety of gender in the protagonists of the features. The data speak for itself; the proportion of female protagonists is higher after the purchase than before. We are aware that the representation of women in Disney animation features has been an object of study and debate for the last years. Based on the accomplished analysis of the character arcs of the female protagonists, we consider that their happiness in Disney progressively starts to depend more on their self-realization and the accomplishment of their goals in detriment of finding true love.

In relation to the amount and variety of master plots each Disney animation feature has, sub-hypothesis 4 is denied. On the one hand, the amount of master plots in each movie remains constant at either one or two throughout all the features. These plots are always represented by the protagonist in those with only one master plot and by the protagonist and the antagonist in those with two plots. On the other hand, it is true that after the purchase, two new master plots are included (riddle and sacrifice), but these only represent 15% of the total number of master plots in the features after the purchase. Therefore, it cannot be concluded that there is a greater variety of master plots.

Following up with the complexity of the plots, there are more significant relationships between the characters of the features released after the purchase than between the characters of the ones released before. When it comes to variety, the types of relationships remain the same, but what does change is the construction of friendship and tyranny. Firstly, as previously shown in the results, friendships after the purchase go through some kind of conflict that leads to the separation of the characters involved, who, at the end, put their friendship above the conflict and help each other. We believe this depiction of friendship is closer to reality and that it even reinforces the real meaning of friendship. Secondly, the tyranny relationships in the features released after the purchase have a backstory that explains where the tyrant comes from. This justifies and depicts the existence of evil and cruelty as possible consequences of life events and not as gratuitous. Therefore, sub-hypothesis 5 can be partially confirmed.

Sub-hypotheses 6 and 7 also lead to a mostly verified hypothesis 2. Even if there are some differences in the percentage of positive reviews given by critics and the audience, generally speaking, it can be said that Disney feature films released after the purchase of Pixar were more accepted and successful for the public than the ones released before.

Our investigation has attempted, ultimately, to contribute to the relevant debate of empowered storytelling in animation as one of the most noticeable traits of the genre between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st. There are, however, shortfalls that should be noted and that, hopefully, could inspire future investigations in a field that we consider particularly important. This is due to the large reach animation has proven to have in different stages of the history of filmmaking and its indisputable effect on generations of particularly vulnerable sectors of the audience. Our paper’s periodization has attempted to present a significantly lengthy period (a quarter of a century), yet future investigations could expand the time frame used to date back to the start of Disney’s renaissance period or update more recent titles created by Pixar after its acquisition by Disney. In a similar vein, the analysis of gender diversity can also benefit from addressing how Disney and Pixar have dealt with gender representation, both when working jointly and separately. The qualitative side of our study has tried to also triangulate with disciplines to transcend the mere film analysis, including disciplines such as psychology that would enrich further analyses of characters and plots. Further studies may, however, expand the qualitative side of our analysis from a film perspective as well.

All things considered, and with the confirmation of both hypotheses, the influence that the purchase of Pixar had on Disney and the changes it brought along have been proven. Pixar replicated, in many ways, Disney’s tireless spirit of evolving and adapting to the times that had been seen in the different stages of the studio’s long history and did it using and expanding what Disney had done in the past, from the technological improvements to ways of telling animated stories. At a narratological level, which has been the center of our study, Pixar’s contribution has empowered changes in gender representation of their protagonists, as well as the arcs of transformation, thus reviving, through storytelling, the leadership of the company at a time when it was starting to be questioned. Adjustment and reactiveness to social changes are also at the core of this shift and quite possibly deserve further studies to apprehend their impact on the relationship between Disney and Pixar in the wake of a new century.