European Institutional Discourse Concerning the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Social Network X

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. European Online Communication: A Shift from Conventional Institutions to the 2.0 Ecosystem

2.1.1. The Role of EU Communication Offices in the Digital Era

2.1.2. Dynamics and Strategies of European Institutions on Social Media

2.2. Hybrid Warfare: Between Conflict and Disinformation

2.2.1. The Era of Post-Truth and Disinformation in Europe

2.2.2. The Importance of Communication in Times of Crisis: The Russian–Ukrainian Case

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Objectives

3.2. Hypotheses

3.3. Analysis Development

3.3.1. Selection Criteria

3.3.2. Procedure for the Execution of Content Analysis

- Ukraine

- Russia

- Ukraine’s

- Russia’s

- Ukrainian

- Russian

- Ukrainians

- Russians

- Kyiv

- Kremlin

- Kiev

- Putin

- Zelensky

- Zelenski

- Poland

- Hungary

- Mariupol

- Donetsk

- Luhansk

3.3.3. Single-Case Study Analysis

3.4. Research Variables and Categories

3.5. In-Depth Interviews

4. Results

4.1. European Commission (@EU_Commission)

4.1.1. Narration Level

4.1.2. Interaction Level

4.1.3. Engagement Level

4.2. European Parliament (@Europarl_EN)

4.2.1. Narration Level

4.2.2. Interaction Level

4.2.3. Engagement Level

4.3. European Council (@EUCouncil)

4.3.1. Narration Level

4.3.2. Interaction Level

4.3.3. Engagement Level

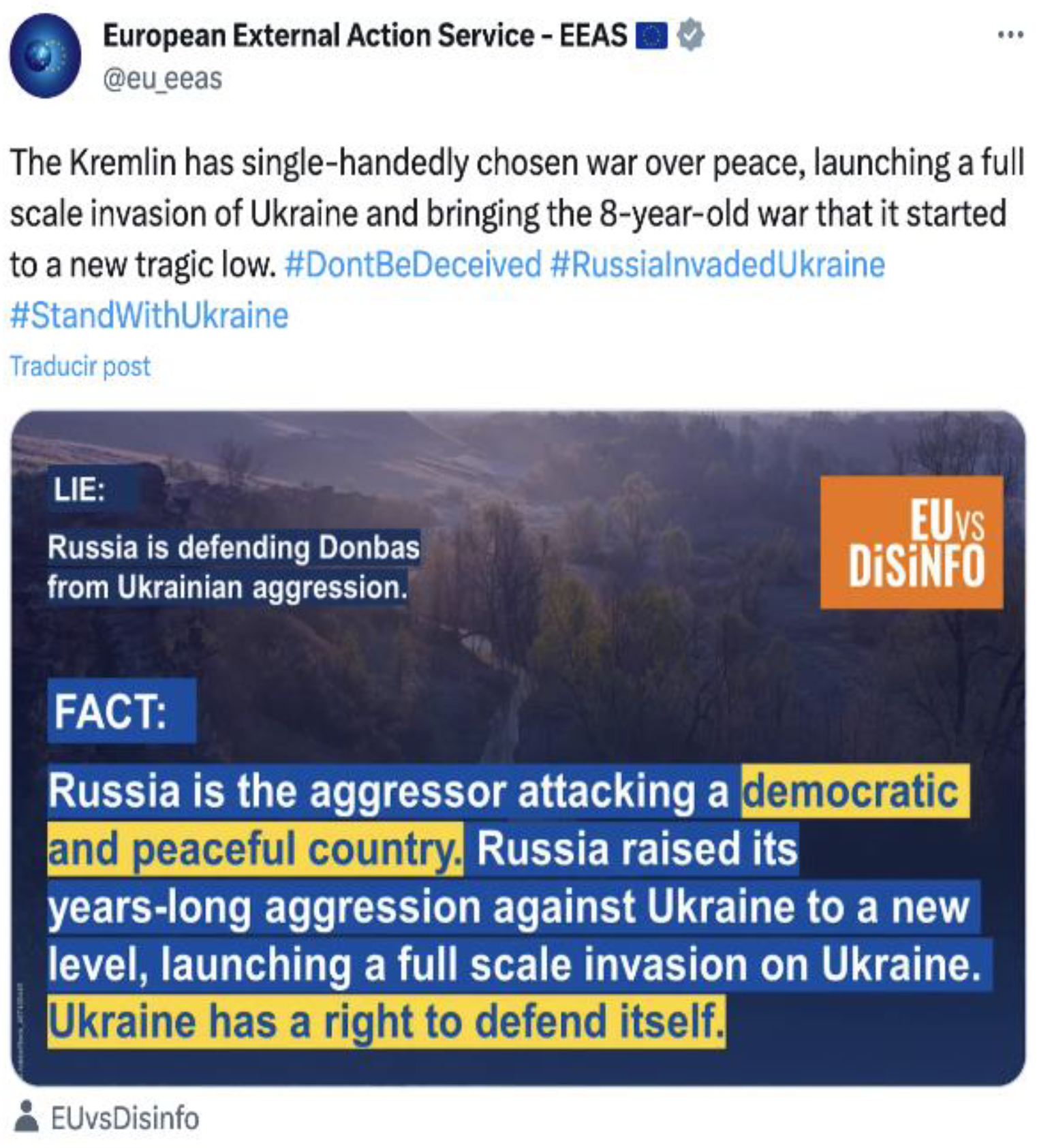

4.4. European External Action Service (@eu_eeas)

4.4.1. Narration Level

4.4.2. Interaction Level

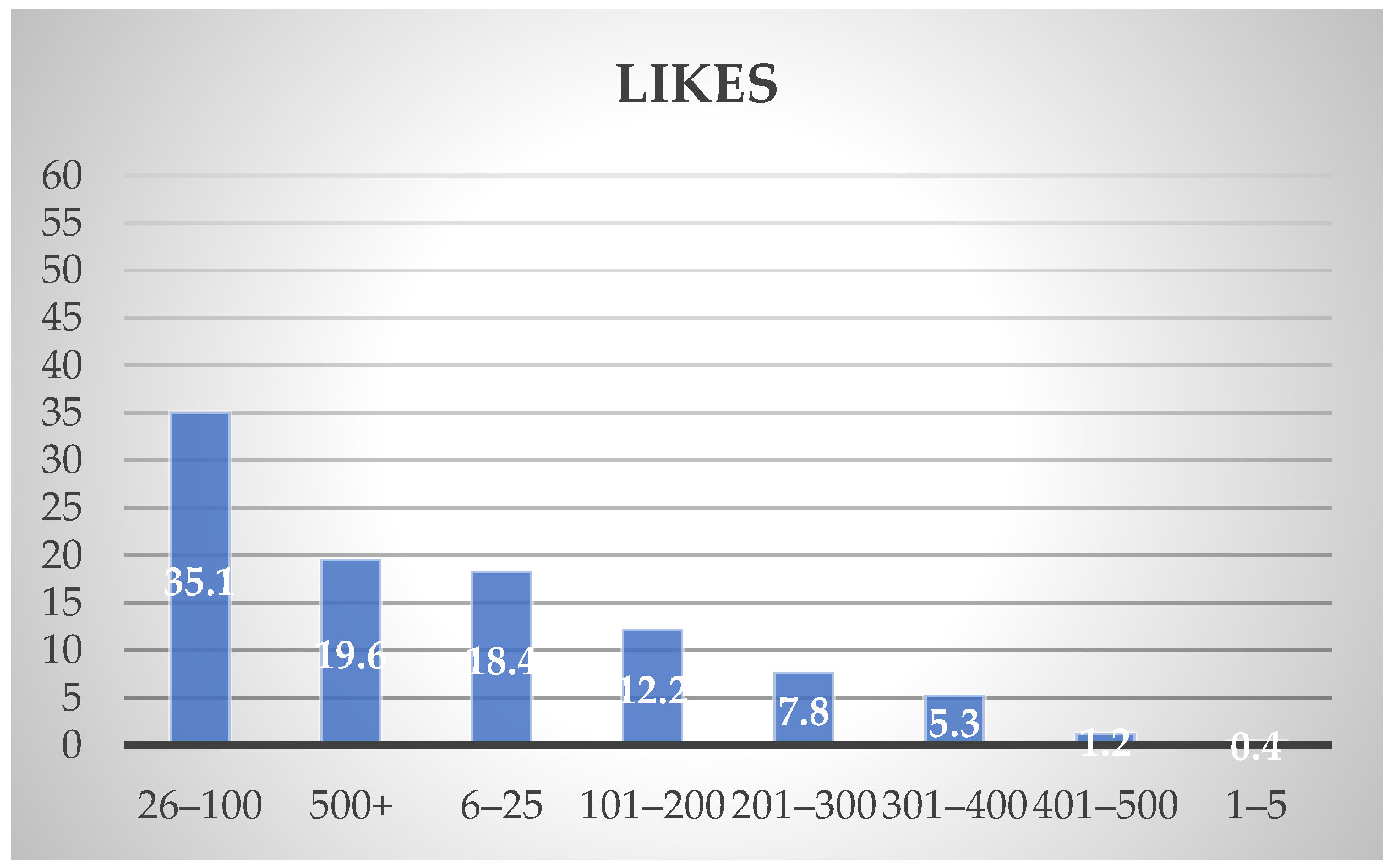

4.4.3. Engagement Level

5. Discussion

5.1. Narration Level

5.2. Interaction Level

5.3. Engagement Level

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Future Reseach Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Code Designed for the Content Analysis

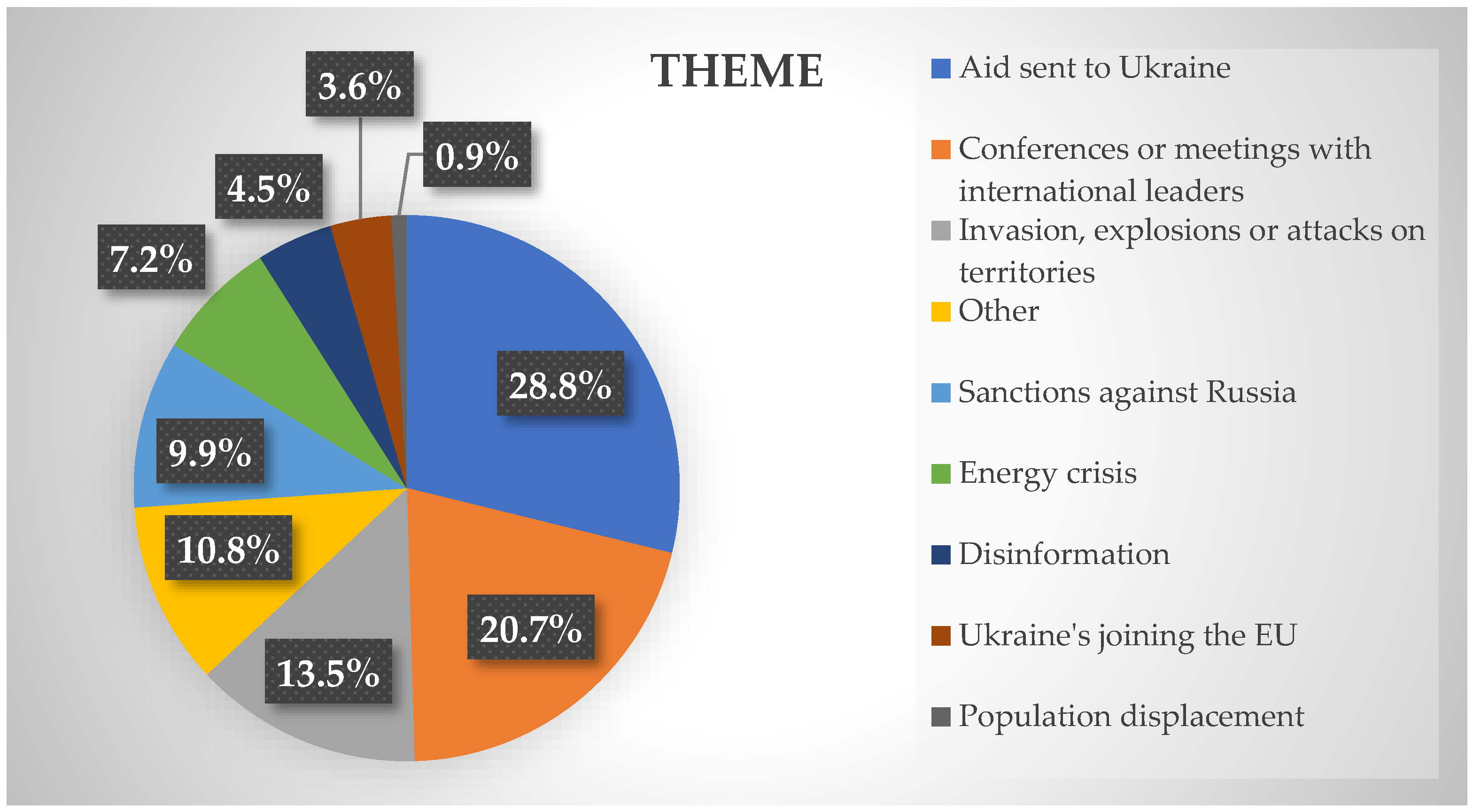

- Aid sent to Ukraine

- Invasion, explosions or attacks on territories

- Population displacement

- Scarcity of goods and services

- Energy crisis

- Sanctions against Russia

- Ukraine’s joining the EU

- Conferences or meetings with international leaders

- Disinformation

- Other

- No #

- Solidarity with Ukraine

- Against violence

- Conflict-related

- Related to Ukraine’s joining the EU

- Migration/refugees/poverty-related

- Energy crisis-related

- Other #

- Express solidarity with the Ukrainian people

- Condemn Kremlin’s actions

- Show support to Zelensky

- Inform about the conflict

- Call to action on an issue

- Reassure or warn citizens about conflict consequences

- Provide conclusions on measures taken

- Other

- Link to their website/social media without multimedia

- Link to their website/social media with other multimedia

- Link to media outlets

- Link to third-party websites/social media

- Image, infographic, or gif

- Video or audio-visual content

- Text only

- Other

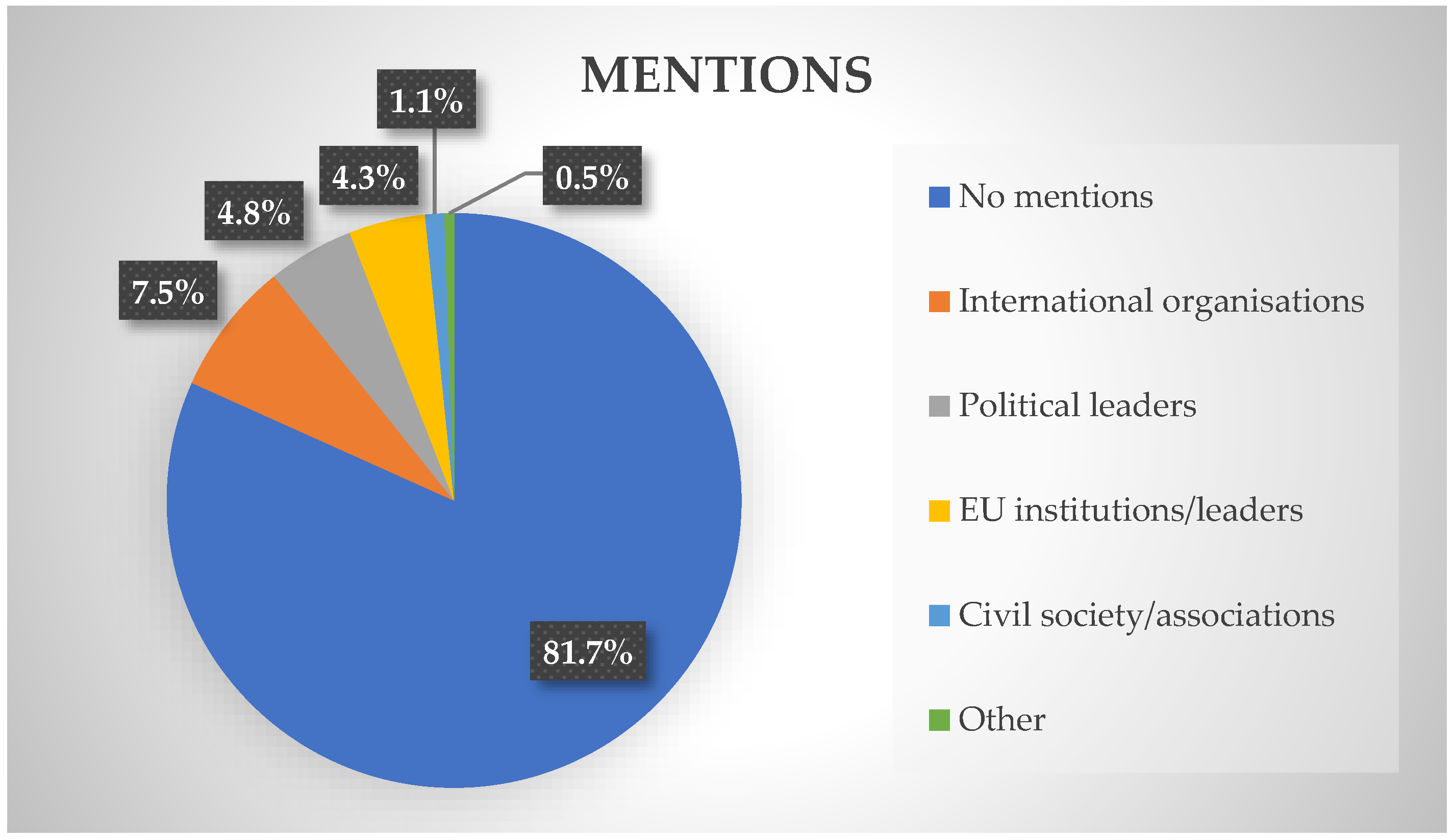

- No mentions

- EU institutions/leaders

- International organisations

- Political leaders

- Academics/researchers/scientists

- Civil society/associations

- Media outlets

- Other actors

- No quotation

- Tweet from EU institutions/leaders

- Tweet from EU Member States’ institutions

- Tweet from political leaders

- Other quotations

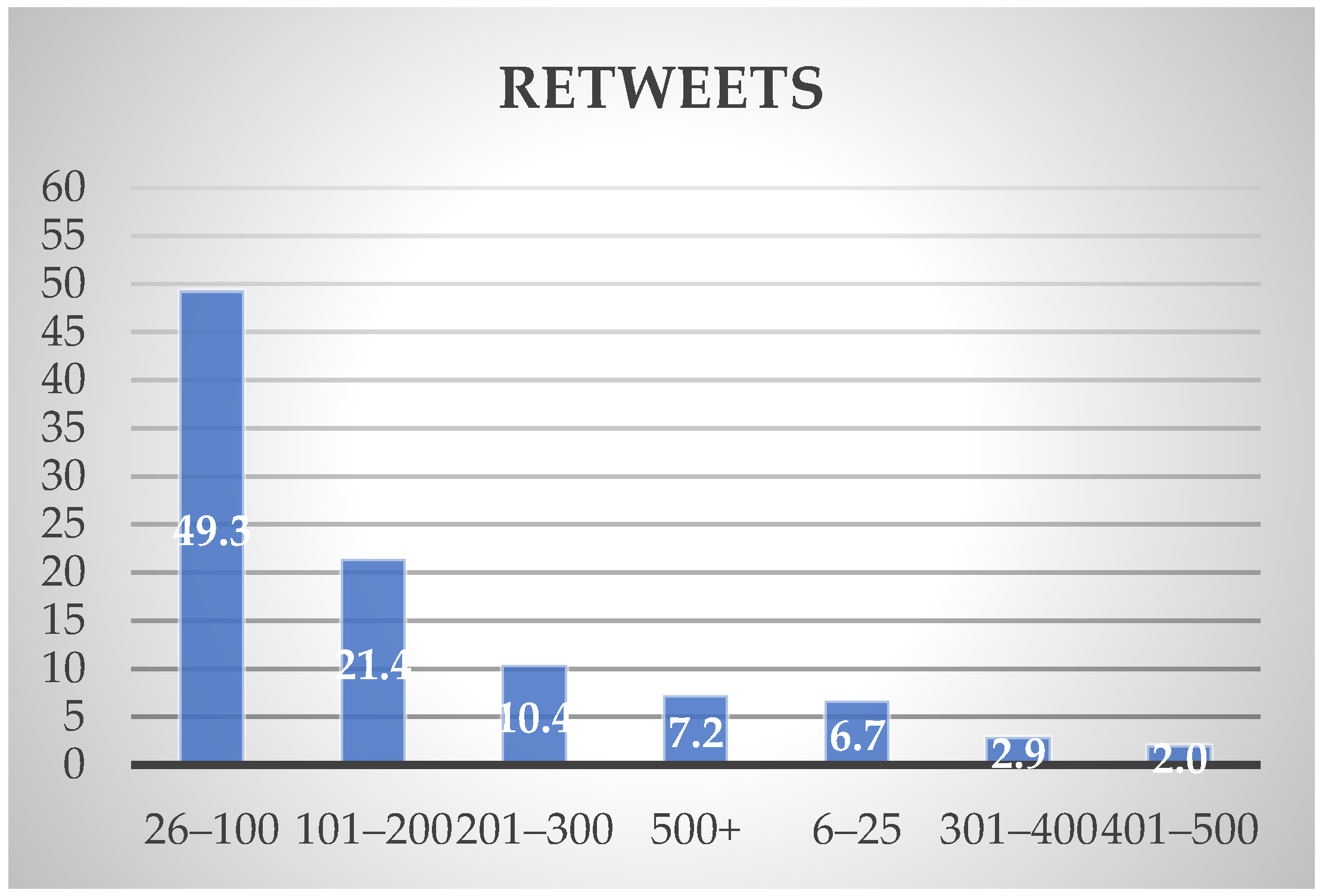

- 1–5

- 6–25

- 26–100

- 101–200

- 201–300

- 301–400

- 401–500

- +500

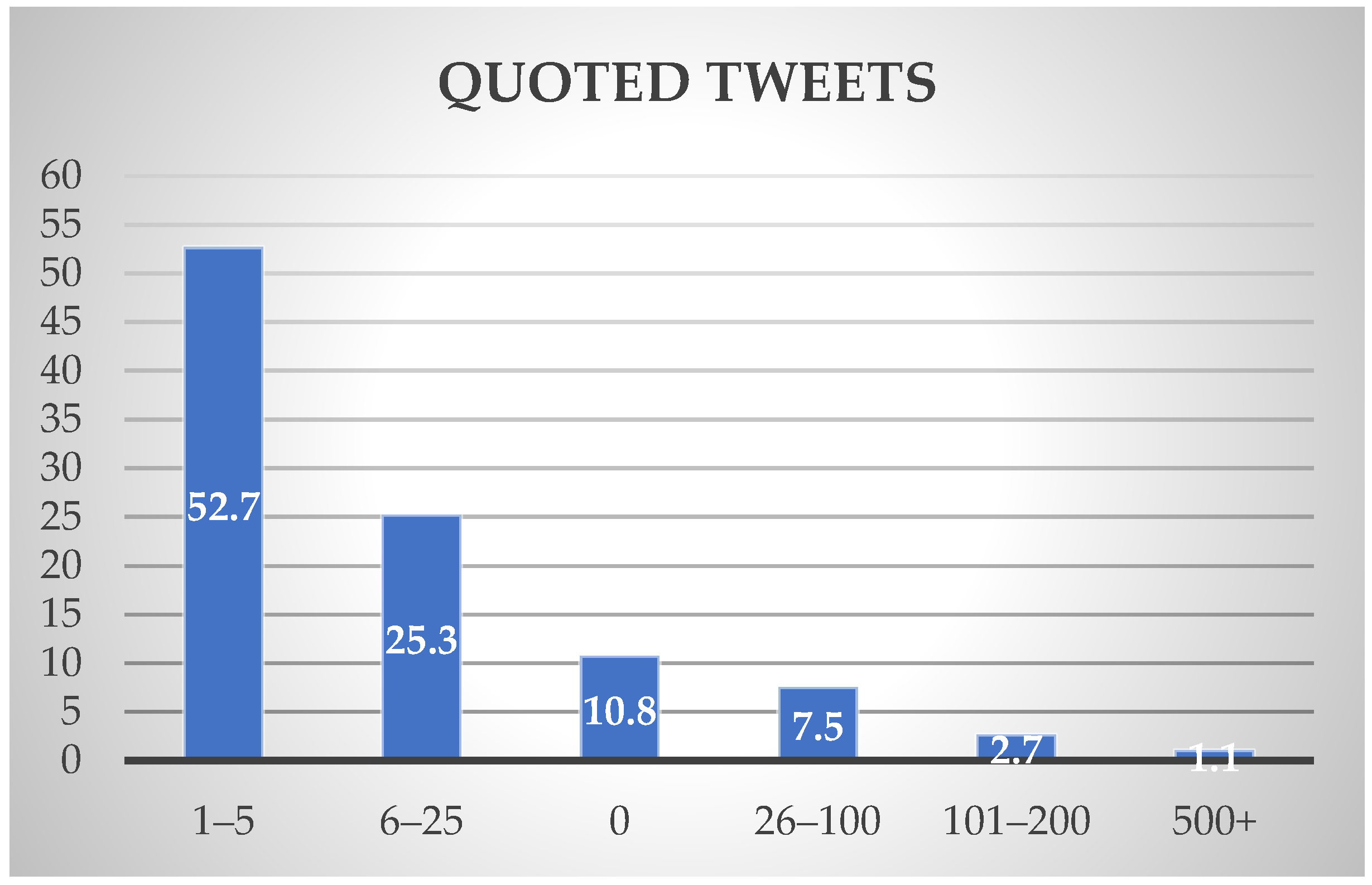

- 0

- 1–5

- 6–25

- 26–100

- 101–200

- 201–300

- 301–400

- 401–500

- +500

- 0

- 1–5

- 6–25

- 26–100

- 101–200

- 201–300

- 301–400

- 401–500

- +500

- 0

Appendix B. Classification and Description of Interviewees’ Profiles for the Research

| Representative | Profile | Position and Institution | Date | ID Code |

| Academics and experts | Political communication, public sphere, and disinformation in the EU | Professor at the Université Libre de Bruxelles and member of various Jean Monnet European Chairs | 3 May 2023 | INT-1 |

| European institutions | EU communication and digital policies | Spokeperson of European Parliament Office in Spain, Public Relations and Institutional Affairs at DG COMM | 1 June 2023 | INT-2 |

| European institutions | Information and communication on EU policies | Assistant in political communication at DG COMM in the European Commission | 31 May 2023 | INT-3 |

| European institutions | EU strategic communication and disinformation | Member of Strategic Communication division and contact for Ukraine and Belarus in Brussels at the European External Action Service | 28 June 2023 | INT-4 |

| European institutions | Information and communication on EU policies | Member of Press team at DG COMM in the European Council | 27 March 2023 | INT-5 |

| Media | International communication and European politics | European politics analyst and international correspondent at Spanish newspapers | 3 May 2023 | INT-6 |

| Social media outreach | EU information | Public Affairs consultant Brussels and content creator on European Affairs on social media | 4 May 2023 | INT-7 |

| European institutions | Information and communication on EU policies | Communication representative at the European Parliament | 9 June 2023 | INT-8 |

References

- Alonso-González, Marián. 2021. Desinformación y coronavirus: El origen de las fake news en tiempos de pandemia. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información 26: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, Rubén, and Hannah Smith. 2021. Digital Communication and Hybrid Threats. Icono 14 19: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisione, Mauro, and Asimina Michailidou. 2017. Social Media and European Politics: Rethinking Power and Legitimacy in the Digital Era. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Basurto, Arman, and Marta Domínguez. 2021. ¿Quién hablará en europeo?: El desafío de construir una unión política sin una lengua común. Madrid: Clave Intelectual. [Google Scholar]

- Battista, Emiliano, Nicola Setari, and Els Rossignol. 2014. The Mind and Body of Europe: A New Narrative. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Benabid, Mohamed. 2022. Policy Center for the New South: Communication Strategies and Media Influence in the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Available online: https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/communication-strategies-and-media-influence-russia-ukraine-conflict (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Bennett, W. Lance. 2012. The Personalization of Politics: Political Identity, Social Media, and Changing Patterns of Participation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 644: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, Alexandra Segerberg, and Curd Knüpfer. 2017. The democratic interface: Technology, political organization, and diverging patterns of electoral representation. Information, Communication & Society 21: 1655–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Marianne Kneuer. 2024. Communication and democratic erosion: The rise of illiberal public spheres. European Journal of Communication 39: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Steven Livingston. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouza, Luis, and Jorge Tuñón. 2018. Personalización, distribución, impacto y recepción en Twitter del discurso de Macron ante el Parlamento Europeo el 17/04/18. El Profesional de la Información 27: 1239–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Dafne, Cristina Renedo Farpón, and María Díez Garrido. 2017. Podemos in the Regional Elections 2015: Online Campaign Strategies in Castille and León. Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas 16: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Domínguez, Eva, Cristina Renedo Farpón, Dafne Calvo, and María Díez-Garrido. 2021. Robot Strategies for Combating Disinformation in Election Campaigns: A Fact-checking Response from Parties and Organizations. In Politics of Disinformation: The Influence of Fake News on the Public Sphere. Edited by Guillermo López-García, Dolors Palau-Sampio, Bella Palomo, Eva Campos-Domínguez and Pere Masip. Londres: Willey Blackwell, pp. 132–45. [Google Scholar]

- Canel, María José, and Karen Sanders. 2012. Government communication: An emerging field in political communication research. The Sage Handbook of Political Communication 2: 85–96. Available online: http://mariajosecanel.com/pdf/emergingfield.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Capati, Andrea. 2019. The Personalisation of Politics in the Age of Social Media: What Risks for European Democracy? Istituto Affari Internazionali. Available online: https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/personalisation-politics-age-social-media-what-risks-european-democracy (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Carral, Uxía, and Jorge Tuñón. 2020. Estrategia de comunicación organizacional en redes sociales: Análisis electoral de la extrema derecha francesa en Twitter. El profesional de la información 29: e290608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu, Jorge Tuñón, and Luis Bouza-García. 2023. The European approach to online disinformation: Geopolitical and regulatory dissonance. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10: 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2009. Comunicación y poder. Barcelona: Editorial UOC. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Nicholas. 2014. The EU’s Information Deficit: Comparing Political Knowledge across Levels of Governance. Perspectives on European Politics and Society 15: 445–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom-Piella, Guillem. 2014. ¿El auge de los conflictos híbridos? Pre-bie3 5: 43. Available online: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_opinion/2014/DIEEEO120-2014_GuerrasHibridas_Guillem_Colom.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Congosto, Mariluz. 2015. Elecciones Europeas 2014: Viralidad de los mensajes en Twitter. Redes. Revista hispana para el análisis de redes sociales 26: 23–52. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=93138738002 (accessed on 3 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Congosto, Mariluz, Pablo Basanta-Val, and Luis Sánchez-Fernández. 2017. T-Hoarder: A framework to process Twitter data streams. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 83: 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, John Ruy. 2015. Continued evolution of hybrid threats. The Three Swords Magazine 28: 19–25. Available online: https://www.jwc.nato.int/images/stories/threeswords/CONTINUED_EVOLUTION_OF_HYBRID_THREATS (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- De Miguel, Bernardo. 2019. Bruselas da por contrarrestadas las campañas rusas de desinformación durante las elecciones europeas. El País. Available online: https://elpais.com/internacional/2019/06/14/actualidad/1560523684_226572.html (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Deželan, Tomaž, Alem Maksuti, and Jernej Prodnik. 2017. Personalization of political communication in social media: The 2014 Slovenian national election campaign. In Social Media and Politics in Central and Eastern Europe. London: Routledge, pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Duch-Guillot, Jaume. 2021. El fenómeno de la desinformación desde el ámbito institucional. In La desinformación en la UE en los tiempos del Covid-19. Edited by César Luena, Juan Carlos Sánchez Illán and Carlos Elías. Barcelona: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 159–67. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Maeve. 2015. Mobile Messaging and Social Media 2015. Pew Research Centre. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/08/19/mobile-messaging-and-social-media-2015/ (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Eckstein, Harry. 1975. Case-study and Theory in Political Science. In Handbook of Political Science, Vol. 7: Strategies of Inquiry. Edited by Fred N. Greenstein and Nelson S. Polsby. Boston: Addison-Westley, pp. 79–137. [Google Scholar]

- Elías, Carlos. 2021. El periodismo como herramienta contra las fake news. In Manual de periodismo y verificación de noticias en la era de las Fake News. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, pp. 19–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2016. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council. Joint Framework on Countering Hybrid Threats: A European Union Response JOIN/2016/018 Final. Available online: https://bit.ly/3pi30b4 (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- European Commission. 2018a. A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Disinformation. Informe del grupo independiente de alto nivel sobre fake news y desinformación en línea. Available online: https://maldita.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/HLEGReportonFakeNewsandOnlineDisinformation.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- European Commission. 2018b. La lucha contra la desinformación en línea: Un enfoque europeo. Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo, al Consejo, al Comité Económico y Social Europeo y al Comité de las Regiones. COM (2018) 236 Final. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2018/ES/COM-2018-236-F1-ES-MAIN-PART-1.PDF (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- European Commission. 2019. Informe sobre la ejecución del Plan de acción contra la desinformación. Alta Representante de la Unión para Asuntos Exteriores y Política de Seguridad. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019JC0012&from=ES (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- European Commission. 2020. Europe Fit for the Digital Age: Commission Proposes New Rules for Digital Platforms. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_2347 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Fazekas, Zoltan, Sebastian Adrian Popa, Hermann Schmitt, Pablo Barberá, and Yannis Theocharis. 2021. Elite-public interaction on Twitter: EU issue expansion in the campaign. European Journal of Political Research 60: 376–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelon, Deen, and David Karpf. 2015. Of big birds and bayonets: Hybrid Twitter interactivity in the 2012 presidential debates. Information, Communication and Society 18: 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán, Juan Antonio, and José Luis Piñuel. 1998. Técnicas de investigación en comunicación social. Elaboración y registro de datos. Madrid: Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- García-Campos, Miguel. 2017. Narrativas europeas: Anatomía de una crisis y cómo salir de ella. Master’s thesis, Escuela Diplomática de España. Academia.edu. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35255267/Narrativas_europeas_Anotom%C3%ADa_de_una_crisis_y_c%C3%B3mo_salir_de_ella (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- García-Gordillo, Mar, Marina Ramos-Serrano, and Rubén Rivas-de-Roca. 2023. Beyond Erasmus. Communication of European Universities alliances on social media. Profesional De La Información 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglietto, Fabio, and Donatella Selva. 2014. Second screen and participation: A content analysis on a full season dataset of tweets. Journal of Communication 64: 260–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, Benjamin. 2018. Thinking in hashtags: Exploring teenagers’ new literacies practices on twitter. Learning, Media and Technology 43: 165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, Jeffrey, and Elisa Shearer. 2016. News Use across Social Media Platforms 2016. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.journalism.org/2016/05/26/news-use-across-social-mediaplatforms-2016/ (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Grill, Christiane, and Hajo Boomgaarden. 2017. A network perspective on mediated Europeanized public spheres: Assessing the degree of Europeanized media coverage in light of the 2014 European Parliament election. European Journal of Communication 32: 568–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, Domenico, and Jorge Tuñón. 2009. El gas ruso y la seguridad energética europea: Interdependencia tras las crisis con Georgia y Ucrania. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internationals 88: 177–99. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40586509 (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- Hänska, Max, and Stefan Bauchowitz. 2019. Can social media facilitate a European public sphere? Transnational communication and the Europeanization of Twitter during the Eurozone crisis. Social Media + Society 5: 231–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sampieri, Roberto, Carlos Fernández-Collado, and Pilar Baptista-Lucio. 2010. Recolección y análisis de los datos cualitativos. In Metodología de la investigación. Edited by Roberto Hernández-Sampieri, Carlos Fernández-Collado and Pilar Baptista-Lucio. Madrid: McGraw-Hill, pp. 418–25. [Google Scholar]

- Herráez, Pedro Sánchez. 2016. Comprender la guerra híbrida… ¿el retorno a los clásicos? Boletín IEEE 4: 304–16. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, John. 2019. Is the EU doing enough to fight fake news? Europe Decides. Available online: http://europedecides.eu/2019/04/is-the-eu-doing-enough-to-fight-fake-news/ (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Hoffman, Donna, and Marek Fodor. 2010. Can You Measure the impact of Your Social Media Marketing? Sloan Management Review 52. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1697257 (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Jiménez-Alcarria, Francisco. 2021. Análisis, impacto y recepción de la estrategia de comunicación digital en Twitter de la UE durante la campaña de vacunación contra la COVID-19. Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Getafe, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Alcarria, Francisco, and Jorge Tuñón-Navarro. 2023. EU digital communication strategy during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign: Framing, contents and attributed roles at stake. Communication & Society 36: 153–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasapoglu, Can. 2015. Russia´s Renewed Military Thinking: Non-Linear Warfare and Reflexive Control. Rome: Research Division. NATO Defense College, p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, John. 2013. Democracy and Media Decadence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, James. 2022. How Democracies Can Overcome the Challenges of Hybrid Warfare and Disinformation. CIDOB. Available online: https://www.cidob.org/en/articulos/cidob_report/n_8/how_democracies_can_overcome_the_challenges_of_hybrid_warfare_and_disinformation (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Kent, Michael Lee. 2013. Using social media dialogically: Public relations role in reviving democracy. Public Relations Review 39: 337–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, Todd. 2003. Issues and Methods in Comparative Politics: An Introduction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lelo, Thales, and Roseli Fígaro. 2021. A Materialist Approach to Fake News. Politics of Disinformation 23: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesaca, Javier. 2018. La disrupción digital en el contexto de las guerras híbridas. Cuadernos de Estrategia 197: 159–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ulrich Ecker, and John Cook. 2017. Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6: 353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijphart, Arend. 1971. Comparative Politics and Comparative Methods. The American Political Science Review 65: 682–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, María. 2022a. Barreras y patologías del proceso comunicativo europeo. In Comunicar Europa en el siglo XXI. Edited by Carlos Barrera and Elsa Moreno. Navarra: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra (EUNSA), pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, María. 2022b. El espacio europeo y el proceso comunicativo europeo. In Comunicar Europa en el siglo XXI. Edited by Carlos Barrera and Elsa Moreno. Navarra: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra (EUNSA), pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Magallón-Rosa, Raúl. 2018. Nuevos formatos de verificación. El caso de Maldito Bulo en Twitter. Sphera Publica 1: 41–65. Available online: http://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/view/341 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Magallón-Rosa, Raúl. 2019. Verificado México 2018. Desinformación y fact-checking en campaña electoral. Revista De Comunicación 18: 234–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majone, Giandomenico. 2014. The general crisis of the European Union: A genetic approach. In The European Union in Crisis or the European Union as Crisis? Edited by John Erik Fossum and Agustín José Menéndez. Oslo: University of Oslo, p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos-García, Silvia. 2018. Las redes sociales como herramienta de comunicación política. Usos políticos y ciudadanos de Twitter e Instagram. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Jaume I, Castelló, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Sáez, Jaime. 2021. Comunicación política y populismos. Análisis de la estrategia digital en Twitter de Podemos durante las campañas europeas de 2014 y 2019. Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Getafe, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Morante, Jorge Juan. 2014. ¿Cómo comunicar Europa a través de las redes sociales? In Europa 3.0. 90 miradas desde España a la UE. Edited by Miguel Ángel Benedicto and Eugenio Hernández. Edited by Miguel Ángel Benedicto and Eugenio Hernández. Madrid: El Reto de Comunicar Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Niciporuc, Tudor. 2014. Comparative analysis of the Engagement Rate on Facebook and Google Plus Social Networks. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/sek/iacpro/0902287.html#download (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Olsson, Eva-Karin, and Kajsa Hammargård. 2016. The rhetoric of the President of the European Commission: Charismatic leader or neutral mediator? Journal of European Public Policy 23: 550–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordiz, Emilio. 2018. El mensaje euroescéptico: Discursos, líderes y reacciones en defensa de la UE. Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad CEU San Pablo, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, Sonny, Omar Moncayo, Kristina Conroy, Doug Jordan, and Timothy B. Erickson. 2020. The Landscape of Disinformation on Health Crisis Communication During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ukraine: Hybrid Warfare Tactics, Fake Media News and Review of Evidence. Journal of Science Communication 19: AO2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha. 2020. Trend towards extreme right-wing populism on Twitter. An analysis of the influence on leaders, media and users. Communication & Society 33: 175–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha, and Alberto Velasco-Molpeceres. 2020. Impacto del discurso político en la difusión de bulos sobre Covid-19. Influencia de la desinformación en públicos y medios. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 78: 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha, and Pilar Limón-Naharro. 2019. Political influencers. A study of Donald Trump’s personal brand on Twitter and its impact on the media and users. Communication & Society 32: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Elisa. 2022. Strategic Disinformation: Russia, Ukraine, and Crisis Communication in the Digital Era. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362022036_Strategic_disinformation_Russia_Ukraine_and_crisis_communication_in_the_digital_era (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Pfetsch, Barbara, and Annett Hertz. 2015. Theorizing communication flows within a European public sphere. In European Public Spheres: Politics Is Back. Edited by Thomas Risse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Quan-Haase, Anabel, and Luke Sloan. 2017. Introduction to the Handbook of Social Media Research Methods: Goals, Challenges and Innovations. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo, Myriam. 2017. La doctrina del post. Posverdad, noticias falsas…Nuevo lenguaje para desinformación clásica. ACOP. March 2. Available online: https://compolitica.com/la-doctrina-del-post-posverdad-noticias-falsas-nuevo-lenguaje-para-desinformacion-clasica/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Rivas-de-Roca, Rubén. 2019. Comunicar la UE en la era de las “fake news”. Ámbitos: Revista Internacional de Comunicación 44: 244–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-de-Roca, Rubén. 2020. Comunicación estratégica transnacional en Twitter para las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2019. Zer 25: 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-de-Roca, Rubén, Concha Pérez-Curiel, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2023. Effects of populism: The agenda of fact-checking agencies to counter European right-wing populist parties. European Journal of Communication 39: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, Leticia. 2019. Desinformación y comunicación organizacional: Estudio sobre el impacto de las fake news. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 74: 1714–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Guillén, David. 2013. La Comunicación en los gabinetes de comunicación en la UE en el siglo XXI: El uso de las TICs. Master’s thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/114815 (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Ruiz-Incertis, Raquel, Rocío Sánchez del Vas, and Jorge Tuñón Navarro. 2024. Análisis comparado de la desinformación difundida en Europa sobre la muerte de la reina Isabel II. Revista De Comunicación 23: 507–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, Ramón, Nataly Buslón, Fernando López-Pan, Bienvenido León, Ignacio López-Goñi, and María del Carmen Erviti. 2020. Desinformación en tiempos de pandemia: Tipología de los bulos sobre la Covid-19. El Profesional de la Información (EPI) 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín-Arce, Ricardo. 2000. La entrevista en el trabajo de campo. Revista de Antropología Social 9: 105. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/RASO/article/view/RASO0000110105A (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Sádaba, Charo, and Ramón Salaverría. 2023. Combatir la desinformación con alfabetización mediática: Análisis de las tendencias en la UE. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 81: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez del Vas, Rocío, and Jorge Tuñón-Navarro. 2024. Disinformation on the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War: Two sides of the same coin? Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Illán, Juan Carlos. 2021. Periodismo frente a desinformación: 2020, el año de la pandemia y de las “fake news”. In La desinformación en la UE en los tiempos del Covid-19. Edited by César Luena, Juan Carlos Sánchez-Illán and Carlos Elías. Barcelona: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 143–49. [Google Scholar]

- Scherpereel, John, Jerry Wohlgemuth, and Margaret Schmelzinger. 2016. The adoption and use of Twitter as a re-presentational tool among members of the European Parliament. European Politics and Society 18: 111–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, Fernando. 2012. Ciudadanía digital y sociedad de la información en la UE. Un análisis crítico. Andamios 9: 259–82. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-00632012000200012 (accessed on 7 December 2022). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suárez-Serrano, Chema. 2020. From bullets to fake news: Disinformation as a weapon of mass distraction. What solutions does International Law provide? SYbIL 24: 129–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasente, Tanase, Mihaela Rus, and Cristian Opariuc-Dan. 2023. Analysis of the online communication strategy of world political leaders during the War in Ukraine (February 24, 2022–January 23, 2023). Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación 156: 246–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Gareth. 2020. Post-Truth Public Relations: Communication in an Era of Digital Disinformation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, Sarah J. 2013. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón, Jorge. 2017. Comunicación internacional. Información y desinformación global en el siglo XXI. Madrid: Fragua. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón, Jorge. 2021a. Desinformación y fake news en la Europa de los populismos en tiempos de pandemia. In Manual de periodismo y verificación de noticias en la era de las fake news. Edited by Carlos Elías and Daniel Teira. Madrid: Ediciones UNED, pp. 249–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, Jorge. 2021b. Europa frente al Brexit, el Populismo y la Desinformación. Supervivencia en tiempos de Fake News. Barcelona: Tirant lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón, Jorge, and Andrea Bouzas. 2023. Extrema derecha europea en Twitter. Análisis de la estrategia digital comunicativa de Vox y Lega durante las elecciones europeas de 2014 y 2019. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación/Mediterranean Journal of Communication 14: 241–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, Jorge, and Carlos Elías. 2021. Comunicar Europa en tiempos de pandemia sanitaria y desinformativa: Periodismo paneuropeo frente a la crisis. In Europa en tiempos de desinformación y pandemia. Periodismo y política paneuropeos ante la crisis del Covid-19 y las Fake News. Edited by Jorge Tuñón and Luis Bouza. Granada: Editorial Comares, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón, Jorge, and Sergio López. 2022. Marcos comunicativos en la estrategia online de los partidos políticos europeos durante la crisis del coronavirus: Una mirada poliédrica a la extrema derecha. El Profesional de la Información 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, Jorge, and Uxía Carral. 2019. Twitter como solución a la comunicación europea. Análisis comparado en Alemania, Reino Unido y España. Revista latina de Comunicación Social 74: 1219–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, Jorge, Álvaro Oleart, and Luis Bouza. 2019. Actores Europeos y Desinformación: La disputa entre el factchecking, las agendas alternativas y la geopolítica. Revista de Comunicación 18: 245–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat-Nejad, Hamed, Mohammad Ghasem Akbari, Fatemeh Salmani, Faezeh Azizi, and Hamid-Reza Nili-Sani. 2023. Russia-Ukraine war: Modeling and Clustering the Sentiments Trends of Various Countries. arXiv arXiv:2301.00604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadier, Johan. 2017. “Post-truth”: A danger to democracy. Études 67: 55–64. Available online: https://www.cairn-int.info/journal--2017-5-page-55.html (accessed on 27 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Valero, Jaime. 2022. Los medios de comunicación y la construcción del relato europeo. In Comunicar Europa en el siglo XXI. Edited by Carlos Barrera and Elsa Moreno. Pamplona: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra (EUNSA), pp. 155–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, Manuel Ángel, and Cristina Pulido. 2020. Más allá de la desinformación y las” fake news”. In Cartografía de la comunicación postdigital: Medios y audiencias en la sociedad de la COVID-19. Edited by Luis Miguel Pedrero Esteban and Ana Pérez Escoda. Madrid: Aranzadi Thomson Reuters, pp. 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova, Nuria. 2014. Comunicar bien Europa, la gran asignatura pendiente. In Europa 3.0. 90 miradas desde España a la UE. Edited by Miguel Ángel Benedicto and Eugenio Hernández. Madrid: El Reto de Comunicar Europa, Plaza y Valdés, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wolter, Lisa-Charlotte, Sylvia Chan Olmsted, and Claudia Fantapié Altobelli. 2017. Understanding Video Engagement on Global Service Networks—The Case of Twitter Users on Mobile Platforms. In Dienstleistungen 4.0. Edited by Manfred Bruhn and Karsten Hadwich. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, pp. 391–409. [Google Scholar]

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Control Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Communication of European Institutions on the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on X @EU_Commission @Europarl_EN @EUCouncil @eu_eeas | Narrative level in tweets about the Russia–Ukraine conflict | Predominant topic |

| Keywords (Hashtags) | ||

| Purpose | ||

| Interaction level in tweets about the Russia–Ukraine conflict | Formal and hypertextual strategies | |

| Mentions Quotations | ||

| Engagement level in tweets about the Russia–Ukraine conflict | Retweets/RT | |

| Likes | ||

| Quoted tweets |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Incertis, R.; Tuñón-Navarro, J. European Institutional Discourse Concerning the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Social Network X. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 1646-1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5040102

Ruiz-Incertis R, Tuñón-Navarro J. European Institutional Discourse Concerning the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Social Network X. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(4):1646-1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5040102

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Incertis, Raquel, and Jorge Tuñón-Navarro. 2024. "European Institutional Discourse Concerning the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Social Network X" Journalism and Media 5, no. 4: 1646-1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5040102

APA StyleRuiz-Incertis, R., & Tuñón-Navarro, J. (2024). European Institutional Discourse Concerning the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Social Network X. Journalism and Media, 5(4), 1646-1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5040102