Populist Leaders as Gatekeepers: André Ventura Uses News to Legitimize the Discourse

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1—How does André Ventura use news to legitimize his political speech on the social media platform X?

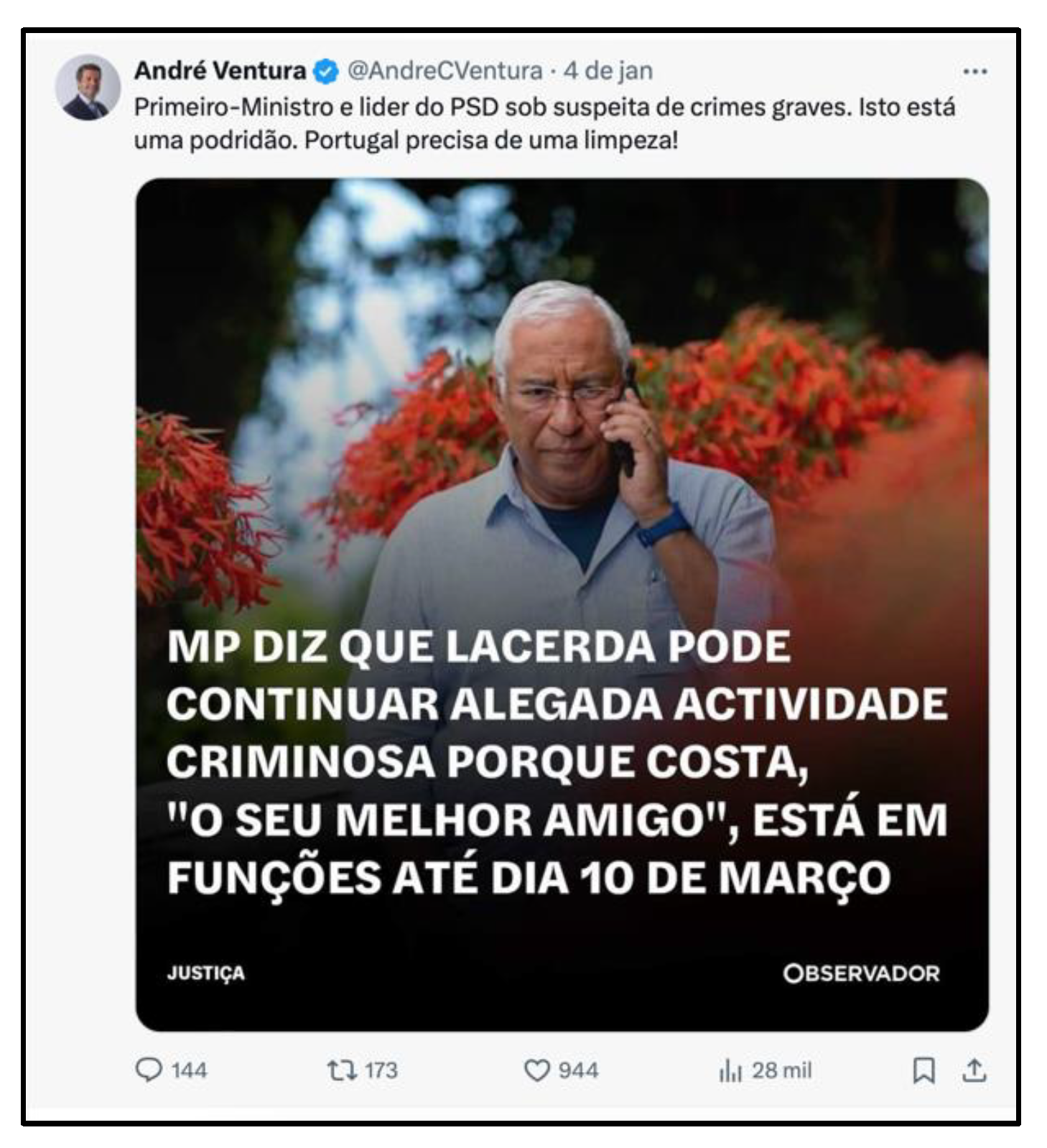

- RQ2—What are the most common rhetorical strategies used by André Ventura when referencing news in his tweets?

- RQ3—Which speeches and behaviors are most often legitimized through André Ventura’s use of news on Twitter?

2. Theoretical Background

3. Methods

3.1. Corpus Selection

3.2. Textual Analysis from Voyant Tools

3.3. Critical Discourse Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Voyant Tools Analysis

4.2. Critical Discourse Analysis: Identifying Topics and Patterns

4.2.1. Immigration

4.2.2. Corruption

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For more information, see https://www.dn.pt/4219714261/president-da-republica-decretou-a-dissolucao-do-parlamento/ (accessed on 8 July 2024). |

| 2 | More information at https://pt.euronews.com/2024/02/26/arrancou-a-campanha-para-as-legislativas-de-10-de-marco (accessed on 8 July 2024). |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

References

- Almeida, Gonçalo. 2024. Ventura foi o político com mais tempo de antena nas televisões em março. Esteve no ar mais 2h30 do que Montenegro. Visão. April. Available online: https://visao.pt/exame/2024-04-09-ventura-foi-o-politico-com-mais-tempo-de-antena-nas-televisoes-em-marco-esteve-no-ar-mais-2h30-do-que-montenegro/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Álvares, Cláudia, and Manuel José Damásio. 2013. Introducing social capital into the ‘polarized pluralist’model: The different contexts of press politicization in Portugal and spain. International Journal of Iberian Studies 26: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auter, Zachary, and Jeffrey Fine. 2016. Negative campaigning in the social media age: Attack advertising on Facebook. Political Behavior 38: 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, and Anabela Gradim. 2022a. A working definition of fake news. Encyclopedia 2: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, and Anabela Gradim. 2022b. Online disinformation on Facebook: The spread of fake news during the Portuguese 2019 election. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 30: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, Daniela Fonseca, Ricardo Domínguez-García, and Concha Pérez-Curiel. 2024. De tweets a tiktoks: Analisando as estratégias digitais do Vox e Chega nas eleições. In (Co)insistências II: Estudos em Letras, Artes e Comunicação. Edited by Daniela Fonseca, Luísa Soares, Natália Amarante and Teresa Moura. Vila Real: CEL, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, João Pedro, Rubén Rivas-de-Roca, Anabela Gradim, and Marlene Loureiro. 2023. The disinformation reaction to the Russia–Ukraine War: An analysis through the lens of Iberian fact-checking. KOME 11: 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnidge, Matthew, Albert Gunther, Jinha Kim, Yangsun Hong, Mallory Perryman, Swee Kiat Tay, and Sandra Knisely. 2020. Politically motivated selective exposure and perceived media bias. Communication Research 47: 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugut, Philip, and Katharina Neumann. 2019. How right-wing extremists use and perceive news media. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96: 696–720. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-Gonzalo, S., P. Zamora-Martínez, and A. González-Neira. 2023. Politainment on Twitter: Engagement in the Spanish Legislative Elections of April 2019. Media and Communication 11: 163–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, Carlo, and Enzo Loner. 2023. Character assassination as a right-wing populist communication tactic on social media: The case of Matteo Salvini in Italy. New Media & Society 25: 2939–60. [Google Scholar]

- Biscaia, Afonso, and Susana Salgado. 2023. The Ukraine-Russia war and the Far Right in Portugal: Minimal impacts on the rising populist Chega party. In The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Edited by Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). [Google Scholar]

- Boomgaarden, Hajo, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2007. Explaining the Rise of Anti-Immigrant Parties: The Role of News media Content. Electoral Studies 26: 404–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracciale, Roberta, Massimiliano Andretta, and Antonio Martella. 2021. Does populism go viral? How Italian leaders engage citizens through social media. Information, Communication & Society 24: 1477–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brake, David. 2014. Sharing Our Lives Online: Risks and Exposure in Social Media. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann, Michael, Silvio Engesser, Frank Büchel, Evelyne Humprecht, and Lars Castro. 2014. Hallin and Mancini revisited: Four empirical types of western media systems. Journal of Communication 64: 1037–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burscher, Bjorn, van Joost Spanje, and Claes de Vreese. 2015. Owning the issues of crime andimmigration: The relation between immigration and crime news and anti-immigrant voting in 11 countries. Electoral Studies 38: 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyens, Willem, Peter Van Aelst, and Steve Paulussen. 2024. Curating the news. Analyzing politicians’ news sharing behavior on social media in three countries. Information, Communication & Society, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Caeiro, Mariana David Ferreira. 2019. Média e populismo: Em busca das raízes da excepcionalidade do caso português. Mestrado’s dissertação, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Domínguez, Eva. 2017. Twitter y la comunicación política. El Profesional de la Información 26: 785–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappella, Joseph, and Kathleen Jamieson. 1997. Spiral of Cynicism. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castelli Gattinara, Pietro, and Caterina Froio. 2024. When the Far right makes the news: Protest characteristics and media coverage of Far-right mobilization in Europe. Comparative Political Studies 57: 419–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvo, Elisabetta, and Walter De Caro. 2020. COVID-19 and newspapers: A content & text mining analysis. European Journal of Public Health 30. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, João Ferreira. 2022. Political Messianism in Portugal, the Case of André Ventura. Slovenská Politologická Revue 22: 79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Melissa-Ellen. 2024. News to me: Far-right news sharing on social media. Information, Communication & Society 27: 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Eatwell, Roger, and Matthew Goodwin. 2020. Nacional-Populismo: A Revolta Contra a Democracia Liberal. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Record. [Google Scholar]

- Egelhofer, Jana Laura, Aaldering Loes, and Sophie Lecheler. 2021. Delegitimizing the media? Analyzing politicians’ media criticism on social media. Journal of Language and Politics 20: 653–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, Mats, and Andrew Morton. 2017. The Performance of Right-Wing Populism. In The Mediated Politics of Europe: A Comparative Study of Discourse. Edited by Mats Ekström and Julie Firmstone. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 289–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ekström, Mats, Marianna Patrona, and Joanna Thornborrow. 2022. News media and the politics of fear: Normalization and contrastive discourses in the reporting on terrorist attacks in Sweden and the UK. Discourse & Society 33: 758–72. [Google Scholar]

- Engesser, Sven, Nicole Ernst, Frank Esser, and Florin Büchel. 2017. Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society 20: 1109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert. 2007. Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication 57: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, Nicole, Sina Blassnig, Sven Engesser, Florin Büchel, and Frank Esser. 2019. Populists Prefer Social Media Over Talk Shows: An Analysis of Populist Messages and Stylistic Elements Across Six Countries. Social Media + Society 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman, and Jane Mulderrig. 2011. Critical Discourse Analysis: A multidisciplinary introduction. In Discourse Studies. Edited by Teun van Dijk. London: SAGE, pp. 357–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Jorge, and Pedro Magalhães. 2020. The 2019 Portuguese General Elections. West European Politics 43: 1038–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, F. 2021. Chega: The Worst of the Portuguese System Now Has a Party. European Left. February 22. Available online: https://prruk.org/chega-the-worst-of-the-portuguese-political-system-now-has-a-party (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Filimonov, Kirill, Uta Russmann, and Jakob Svensson. 2016. Picturing the party: Instagram and party campaigning in the 2014 Swedish elections. Social Media + Society 2: 205630511666217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, Robert. 2011. Democratic practice after the revolution: The case of Portugal and beyond. Politics & Society 39: 233–67. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Scott. 1987. Value change in industrial societies. American Political Science Review 81: 1303–19. [Google Scholar]

- Freelon, Deen, Michael Bossetta, Chris Wells, Josephine Lukito, Yiping Xia, and Kirsten Adams. 2020. Black trolls matter: Racial and ideological asymmetries in social media disinformation. Social Science Computer Review 40: 560–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudette, Tiana, Ryan Scrivens, Garth Davies, and Richard Frank. 2021. Upvoting extremism: Collective identity formation and the extreme right on Reddit. New Media & Society 23: 3491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2014. Populism 2.0. In Social Media, Politics and the State: Protests, Revolutions, Riots, Crime and Policing in the Age of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Edited by Daniel Trottier and Christian Fuchs. New York: Routledge, pp. 16–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2018. Social media and populism: An elective affinity? Media, Culture & Society 40: 745–53. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, Debbie, Richard Ling, Liuyu Huang, and Doris Liew. 2019. News sharing as reciprocal exchanges in social cohesion maintenance. Information, Communication & Society 22: 1128–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gründl, Johann. 2022. Populist ideas on social media: A dictionary-based measurement of populist communication. New Media & Society 24: 1481–99. [Google Scholar]

- Haanshuus, Birgitte, and Karoline Andrea Ihlebæk. 2021. Recontextualizing the news: How antisemitic discourses are constructed in extreme far-right alternative media. Nordicom Review 42: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Daniel, and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hallin, Daniel, and Paolo Mancini. 2017. Ten Years After Comparing Media Systems: What Have We Learned? Political Communication 34: 155–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, Michael. 2020. My reality is more truthful than yours: Radical right-wing politicians’ and citizens’ construction of “fake” and “truthfulness” on social media—Evidence from the United States and the Netherlands. International Journal of Communication 14: 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Xiaoming, Nainan Wen, and Cherian George. 2014. News consumption and political and civic engagement among young people. Journal of Youth Studies 17: 1221–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, Tobias, Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Petro Tolochko, Fabienne Lind, and Hajo Boomgaarden. 2024. My voters should see this! What news items are shared by politicians on Facebook? The International Journal of Press/Politics 29: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignazi, Piero. 1992. The silent counter-revolution. Hypotheses on the emergence of extreme right-wing parties in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 22: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1971. The silent revolution in Europe: Intergenerational change in postindustrial societies. American Political Science Review 65: 991–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittefaq, Muhammad, Shafiq Ahmad Kamboh, Azhar Iqbal, Uwah Iftikhar, Mauryne Abwao, and Rauf Arif. 2022. Understanding public reactions to state security officials’ suicide cases in online news comments. Death Studies 47: 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo, Daniel. 2021. Constructing the “good Portuguese” and their enemy-others: The discourse of the far-right Chega party on social media. Doctoral Dissertation, ISCTE, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Elihu, and Paul Lazarsfeld. 1955. Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kissas, Angelos. 2020. Performative and ideological populism: The case of charismatic leaders on Twitter. Discourse & Society 31: 268–84. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, Benjamin. 2017. Populist online practices: The function of the Internet in right-wing populism. Information, Communication & Society 20: 1293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2004. Strategic Political Communication: Mobilizing Public Opinion. In Audience Democracies. Edited by Frank Esser and Barbara Pfetsch. Communication, Society and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżanowski, Michal, and Mats Ekström. 2022. The normalization of far-right populism and nativist authoritarianism: Discursive practices in media, journalism and the wider public sphere/s. Discourse & Society 33: 719–29. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. Populism: What’s in a Name. In Empire & Terror: Nationalism/Postnationalism in the New Millennium. Edited by Begoña Aretxaga, Dennis Dworkin, Joseba Gabilondo and Joseba Zulaika. Nevada: University of Nevada. [Google Scholar]

- Lisi, Marco, Edalina Sanches, and Jayane dos Santos Maia. 2021. Party System Renewal or Business as Usual? Continuity and Change in Post-Bailout Portugal. South European Society and Politics 25: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, Guillermo. 2016. ‘Nuevos’ y ‘viejos’ liderazgos: La campaña de las elecciones generales españolas de 2015 en Twitter. Communication & Society 29: 149–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti, Maria Ivana. 2020. Right-wing Populism and the Representation of Immigrants on Social Media. A Critical Multimodal Analysis. Iperstoria 15: 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- Malhado, Alexandre. 2024. As viagens do Chega para aprender com o Vox. Sábado. February 1. Available online: https://www.sabado.pt/portugal/detalhe/as-viagens-do-chega-para-aprender-com-o-vox (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Mancosu, Moreno, Salvatore Vassallo, and Cristiano Vezzoni. 2017. Believing in Conspiracy Theories: Evidence from an Exploratory Analysis of Italian Survey Data. South European Society and Politics 22: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, Valentina. 2020. O Chega é um partido com rosto mas sem coluna vertebral. Diário de Notícias. June 25. Available online: https://www.dn.pt/edicao-do-dia/25-jun-2020/a-campanha-presidencial-e-uma-janela-de-oportunidade-unica-a-medida-do-estilo-de-andre-ventura-12348874.html (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Marchi, Riccardo. 2023. The populist radical right in 21st-century portugal. In Portugal Since the 2008 Economic Crisis: Resilience and Change. Edited by António Costa Pinto. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, Alice, and Rebecca Lewis. 2017. Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. New York: Data & Society Research Institute, pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, Alice, Benjamin Clancy, and Katherine Furl. 2022. Far-Right Online Radicalization: A Review of the Literature. Chapel Hill: The Bulletin of Technology & Public Life. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, Gianpietro, and Roberta Bracciale. 2019. La Politica Pop Online: I Meme e le Nuove Sfide Della Comunicazione Politica [Pop Politics Online: Memes and the New Challenges of Political Communication]. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Meikle, Graham, and Sherman Young. 2011. Media Convergence: Networked Digital Media in Everyday Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, Raquel. 2021. Marcelo vs. André Ventura: Da acusação “dos bandidos” às direitas que os distinguem. TSF. January 6. Available online: https://www.tsf.pt/portugal/politica/marcelo-vs-andre-ventura-da-acusacao-dos-bandidos-as-direitas-que-os-distinguem-13202612.html (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Mendes, Mariana. 2021. ‘Enough’of What? An Analysis of Chega’s Populist Radical Right Agenda. South European Society and Politics 26: 329–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, Mariana, and James Dennison. 2021. Explaining the emergence of the radical right in Spain and Portugal: Salience, stigma and supply. West European Politics 44: 752–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, Solomon, and Sean Westwood. 2014. Selective exposure in the age of social media: Endorsements trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online. Communication Research 41: 1042–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Michael. 2001. Between theory, method, and politics positioning of the approaches of CDA. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. Newcastle upon Tyne: SAGE, pp. 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mindich, David. 2000. Just the Facts: How” objectivity” came To Define American Journalism. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, Benjamin. 2015. How to perform crisis: A model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Government and Opposition 50: 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, Benjamin. 2016. The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, Benjamon, and Simon Tormey. 2014. Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style. Political Studies 62: 381–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39: 541–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Novais, Rui. 2022a. On the firing line: Adversariness in the Portuguese investigative reporting of far-right populism. Media & Jornalismo 22: 301–18. [Google Scholar]

- Novais, Rui. 2022b. Vigiando o Populismo: Concepção, desempenho e negociação dos papéis jornalísticos na cobertura da extrema direita em Portugal. Brazilian Journalism Research 18: 316–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, Rui. 2023. A game of masks: The communicative performance of the Portuguese populist far-right. In Masks and Human Connections: Disruptive Meanings and Cultural Challenges. Edited by Luísa Magalhães and Cândido Oliveira Martins. London: Springer, pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Orazani, Seyed Nima, Michael Wohl, and Bernhard Leidner. 2020. Perceived normalization of radical ideologies and its effect on political tolerance and support for freedom of speech. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 23: 1150–70. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, Nuno, Paulo Couraceiro, Inês Narciso, José Moreno, and Gustavo Cardoso. 2021. André Ventura: A Criação da Celebridade Mediática. Available online: https://medialab.iscte-iul.pt/andre-ventura-a-criacao-da-celebridade-mediatica/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha. 2020. Trend towards extreme right-wing populism on Twitter. An analysis of the influence on leaders, media and users. Comunicación y sociedad = Communication & Society 33: 175–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha, and João Pedro Baptista. 2024. Lying on social media. Disinformation strategies of Iberian populist radical right. In Handbook of Political Communication in Ibero-America. Edited by Andreu Casero Ripollés and Carlos López-López. London: Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Curiel, Concha, and Ricardo Domínguez García. 2021. Discurso político contra la democracia. Populismo, sesgo y falacia de Trump tras las elecciones de EE UU (3-N). Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación = Culture, Language and Representation 26: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Barbara, and Ryan Scrivens. 2016. White pride worldwide: Constructing global identities online. In The Globalization of Hate: Internationalizing Hate Crime. Edited by Jennifer Schweppe and Mark Walters. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, Richard, and John Cacioppo. 1986. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion. London: Springer, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Polletta, Francesca, and James Jasper. 2001. Collective identity and social movements. Annual Review of Sociology 27: 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, Hélder. 2024. Social media and the rise of radical right populism in Portugal: The communicative strategies of André Ventura on X in the 2022 elections. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Antón, Rubén, and Carla Baptista. 2022. Populism and social media in the Iberian Peninsula: The use of Twitter by VOX (Spain) and Chega (Portugal) in election campaigning. International Journal of Iberian Studies 35: 125–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, Zvi. 2010. Source credibility as a journalistic work tool. In Journalists, Sources, and Credibility. London: Routledge, pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, José Pedro. 2020. André Ventura–por Portugal pelos portugueses. MovimentAção 7: 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydgren, Jens. 2018. The Radical Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, Susana. 2019. Where’s populism? Online media and the diffusion of populist discourses and styles in Portugal. European Political Science 18: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, Susana. 2022. Mass Media and Political Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press EBooks, pp. 308–22. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, Susana, and José Pedro Zúquete. 2016. Portugal: Discreet populisms amid unfavorable contexts and stigmatization. In Populist Political Communication in Europe. Edited by Toril Aalberg, Frank Esser, Carsten Reinemann, Jesper Stromback and Claes De Vreese. London: Routledge, pp. 235–48. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Pereira, José. 2016. The Portuguese media system and the normative roles of the media: A comparative view. Análise Social 51: 780–801. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Rita, and Sílvia Roque. 2021. The Populist Far-right and the Intersection of Anti-immigration and Antifeminist Agendas: The Portuguese Case. DiGeSt: Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies 8: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwemmer, Carsten. 2021. The limited influence of right-wing movements on social media user engagement. Social Media+ Society 7: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, Stéfan, and Geoffrey Rockwell. 2020. Voyant-Tools. Available online: https://voyant-tools.org (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Serrano, E. 2014. Sistema dos media em Portugal: Os primeiros anos após a instauração da democracia. In Cobertura Jornalística da Corrupção Política: Sistemas Políticos, Sistemas Mediáticos e Enquadramentos Legais. Edited by Isabel Ferin Cunha and Estrela Serrano. Lisbon: Alêtheia Editores, pp. 149–75. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini. 2010. Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication 60: 556–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, Joelle, Chris Peters, and Marcel Broersma. 2019. Sharing and discussing news in private social media groups: The social function of news and current affairs in location-based, work-oriented and leisure-focused communities. Digital Journalism 7: 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, Kjerstin, and Chris Wells. 2016. Curated flows: A framework for mapping media exposure in the digital age. Communication Theory 26: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, Teun. 1993. Principles of Critical Discourse Analysis. Discourse & Society 4: 249–83. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, Teun. 1998. Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, Teun. 2001. Multidisciplinary CDA: A plea for diversity. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, pp. 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2007. Legitimation in discourse and communication. Discourse & Communication 1: 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth. 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Michael Meyer. 2009. Critical Discourse Analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis 2: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

| Top 10 | Words | n | Co-Occurrences |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Portugal | 31 | Policy (3), to finish (3), we want (2) |

| 2 | Chega | 23 | I took (2), situation (2), reason (2) |

| 3 | Portuguese | 17 | Truth (3), security (2), stupid (2) |

| 4 | Country | 15 | It needs (3), to go back (2), Portugal (2) |

| 5 | Security | 9 | Portuguese (2), forces(2), control (2) |

| 6 | PS | 9 | Vote (1), enables (1), tics (1) |

| 7 | Policy | 9 | Result (3), Portugal (3), immigration (3) |

| 8 | Immigration | 9 | Policy (3), ilegal (2), out of control (2) |

| 9 | Control | 9 | Borders (4), security (2), rules (2) |

| 10 | Money | 8 | Health (3), we will have (1), to know (1) |

| Category | Word | Positive Correlation (Words) |

|---|---|---|

| Nationalism and National Sovereignty | Portugal | Wide open (r = 0.76, p = 0.01) |

| Borders (r = 0.74, p = 0.01) | ||

| Portuguese | Immigrants (r = 0.65, p = 0.03) | |

| Borders | Control (r = 0.07, p = 0.01) | |

| Control | - | |

| We (our) | - | |

| Criticism of the EU | Europe | Wide open (r = 0.76, p = 0.01) Control (r = 0.63, p = 0.04) |

| Immigration | Immigration | Uncontrolled (r = 0.80, p < 0.001) |

| Foreigners (r = 0.80, p < 0.001) | ||

| Illegal (r = 0.61, p = 0.05) | ||

| Immigrant | Illegal (r = 0.83, p < 0.001) | |

| Extinction (r = 0.72, p = 0.01) | ||

| Government (r = 0.61, p = 0.05) | ||

| Nationality | Illegal (r = 0.76, p = 0.01) | |

| Uncontrolled (r = 0.76, p = 0.01) | ||

| Law (r = 0.76, p = 0.01) | ||

| Enter (r = 0.76, p = 0.01) | ||

| Immigration (r = 0.72, p = 0.01) | ||

| Migrations (r = 0.71, p = 0.01) | ||

| Extinction (r = 0.66, p = 0.03) | ||

| SEF | Illegal (r = 0.93, p < 0.001) | |

| Imports (r = 0.88, p < 0.001) | ||

| Immigrants (r = 0.81, p < 0.001) | ||

| Migrations (r = 0.75, p = 0.01) | ||

| Reverse (r = 0.75, p = 0.01) | ||

| Nationality (r = 0.71, p = 0.01) | ||

| (In)security | Security | Criminality (r = 0.65, p = 0.04) |

| Insecurity | Climate (r = 0.81, p < 0.001) | |

| Criminality (r = 0.70, p = 0.01) | ||

| Daily (r = 0.70, p = 0.02) | ||

| Assault | To happen (r = 0.75, p = 0.01) | |

| Police | Convicted (r = 0.82, p < 0.001) | |

| Criteria (r = 0.82, p < 0.001) | ||

| People (r = 0.82, p < 0.001) | ||

| Bandit (r = 0.65, p = 0.01) | ||

| Social politics | Gender Ideology | - |

| LGBT | - | |

| Justice (Severe Penalties) | Prison | Assaults (r = 0.93, p = 0.001) |

| Politicians (r = 0.76, p = 0.01) | ||

| Doors (r = 0.67, p = 0.03) | ||

| Penalty | - | |

| Corruption | Corruption | Taxpayers (r = 0.71, p = 0.01) |

| Cushy job | Corruption (r = 0.93, p < 0.001) | |

| PS (r = 0.84, p < 0.001) | ||

| Minister (r = 0.82, p = 0.003) | ||

| Clean-up (r = 0.74, p = 0.01) | ||

| Acabar (r = 0.72, p = 0.01) | ||

| Shady deals (r = 0.66, p = 0.03) | ||

| PSD (r = 0.65, p = −0.05) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baptista, J.P.; Gradim, A.; Fonseca, D. Populist Leaders as Gatekeepers: André Ventura Uses News to Legitimize the Discourse. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 1329-1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030084

Baptista JP, Gradim A, Fonseca D. Populist Leaders as Gatekeepers: André Ventura Uses News to Legitimize the Discourse. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(3):1329-1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030084

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaptista, João Pedro, Anabela Gradim, and Daniela Fonseca. 2024. "Populist Leaders as Gatekeepers: André Ventura Uses News to Legitimize the Discourse" Journalism and Media 5, no. 3: 1329-1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030084

APA StyleBaptista, J. P., Gradim, A., & Fonseca, D. (2024). Populist Leaders as Gatekeepers: André Ventura Uses News to Legitimize the Discourse. Journalism and Media, 5(3), 1329-1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5030084