Abstract

In an era dominated by the digital revolution, the distribution of information has undergone a profound transformation. The duality of “quality journalism” and “viral journalism” has become an important theme in the modern media landscape. This paper explores the scope of information dissemination, dissecting the fundamentals, challenges, characteristics, and trends associated with both “quality” and “viral” journalism. Utilizing the Greek political scene as a case study, this paper aims to examine the tensions and trade-offs inherent in journalistic practices within the context of contemporary information dissemination. Analyzing closely media coverage surrounding events such as the election of Stefanos Kasselakis, the new President of the SYRIZA-Progressive Alliance party, we seek to elucidate the delicate balance between viral and quality journalism. By shedding light on these dynamics, our study aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how journalism navigates the tension between virality and quality within the Greek political sphere in a “post-politics” era.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary digital landscape, journalism is undergoing transformational change driven by the coexistence of two distinct models: “viral journalism” and “quality journalism”. Scholars such as Anderson (2011), Boczkowski et al. (2018), and Jenkins et al. (2013) have contributed significantly to defining these terms. “Viral journalism”, exemplified by clickbait, sensationalism, and rapid online dissemination, thrives on the power of social media algorithms and the lure of instant gratification. In contrast, “quality journalism” remains true to its commitment to rigorous investigation, fact-checking, and ethical responsibility, embodying core values of credibility, accuracy, and honesty. This paper will examine the characteristics, multifaceted implications, and complex challenges associated with each approach, explaining their profound impact on the media ecosystem and social discourse.

The tension between these models goes beyond simple editorial choices and includes complex issues such as trade-offs between virality and accuracy, manipulation of public discourse by misinformation bias, and the erosion of trust in news organizations. This paper will highlight the integral role of “quality journalism” in balancing these distortions, promoting informed citizenship, and defending fundamental principles of democracy. A harmonious coexistence between virality and accuracy can be built through a collaborative effort between media organizations, digital platforms, and regulators. By dissecting the dichotomy between “viral journalism” and “quality journalism”, this paper will not only try to enrich our understanding of the contemporary media environment but also will argue for a radical approach. The focus is on balancing the appeal of virality with people’s demands for truth, accountability, and the well-being of democratic societies. More specific, the following paper employs a qualitative textual analysis of news articles from four Greek news organizations, examining media coverage of Stefanos Kasselakis’ election. By analyzing these articles, the study aims to elucidate the balance between “viral” and “quality” journalism.

3. Materials and Methods

The main methodological tool for this study is content analysis, which aims at the unveiling of social reality. When conducting content analysis, one approaches a written text to uncovering data that can verify the relation between subjectivity and objectivity.

To illustrate the dynamic between “quality journalism” and “viral journalism” and delve more into its features, we look at the case of Stefanos Kasselakis, which is used as an example to highlight how certain stories “go viral” and what are the effects on the credibility of the content.

“Viral content” is known for attractive headlines containing a question or a series of images. Also, content that evokes a lot of emotion from the reader is more likely to go viral (Berger and Milkman 2013). The ability of these types of features to influence the audiences explains, to a great extent, why so many media outlets have adopted them. Many articles are often written in shorter lengths and sometimes with more humor (Tandoc and Jenkins 2017).

This analysis is an attempt to explain the selection of specific features and their potential influence on readers. As such, it does not permit any generalization of results.

Collection and Analysis: The Case of Stefanos Kasselakis

This study is based on a qualitative analysis of articles from four online media outlets in Greece that referred to Stefanos Kasselakis, the new leader of the Greek political party SYRIZA-Progressive Alliance party, either in their headlines or their news leads.

The sample under analysis is taken from the following sites: protothema.gr, iefimerida.gr, thepressproject.gr, and insidestory.gr. Inside story is a medium with a monthly subscription that focuses on offering independent, investigative, and in-depth journalism on a wide range of topics. ThePressProject is a reader-funded, open-access media outlet in Greece that does not accept any funding from political or banking institutions. It publishes political analyses and investigative reports and places particular emphasis on international journalistic cooperation and multimedia content. Both protothema and iefimerida belong to the most popular Greek online media. Protothema is also known for its populist orientation.

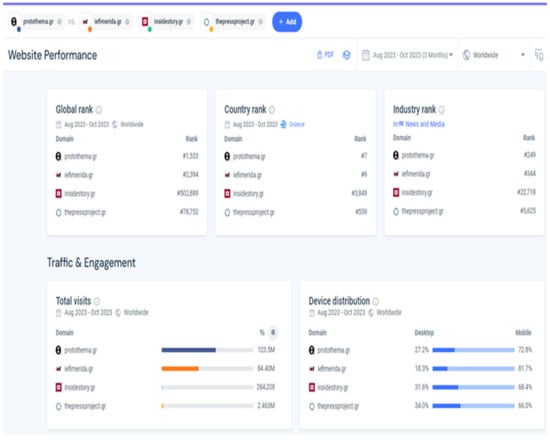

There were two criteria by which the online newspapers listed in Table 1 were selected. The first has to do with the traffic of the websites, and the second is related to the type of funding, whether it is advertising-based or subscription-based media. Regarding traffic, we derived the data from the ranking of the online platform similarweb.com. SimilarWeb.com is a website and a digital marketing intelligence platform that provides insights and data about website traffic, user engagement, and online market trends (see Figure 1). It gathers data from various sources, including web crawlers, ISP data, and proprietary algorithms, to estimate website traffic, visitor demographics, referral sources, and more. Based on the above website ranking system, protothema.gr comes first in traffic, followed by iefimerida.gr, insidestory.gr, and finally, thepressproject.gr. In terms of funding, the first two online media rely on advertising, unlike the next two, which base their revenues on subscriptions and reader donations.

Table 1.

Source of articles for analysis.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the website similarweb.com showing the performance of the four online newspapers from August to October 2023.

Stefanos Kasselakis, with no prior political experience in the politics of Greece, crashed with the force of an asteroid on current Greek political and media life. Openly gay, alleged shipowner, American-bred, presumably charismatic, yet previously unknown, he made the huge leap from obscurity to becoming leader of the second largest party, SYRIZA. He has been several times characterized as “Messiah” both from the national media and his political opponents.

The period of analysis was limited to articles published in September 2023, when news about Stefanos Kasselakis and his candidacy for the presidency in the party’s upcoming internal elections that would be held on 17 September 2023, first broke out.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that headlines play a crucial role in news articles. They offer readers context, help them understand the information better, and stimulate the interpretation of the content by triggering relevant background knowledge (Bransford and Johnson 1972; Dor 2003; Ifantidou 2009). Furthermore, among the defining features of clickbait, the headline is considered the most important bait, given its critical significance in the selection of news (Bazaco et al. 2019). According to Chakraborty et al. (2016) and their linguistic analysis, clickbait headlines, as opposed to non-clickbait headlines, tend to have longer sentences that contain both substantive elements (specific references) and functional words (words with ambiguous meanings). In addition, clickbait headlines tend to contain more frequently used words and highly positive language. In particular, they often address the reader directly using first- and second-person pronouns. This is a departure from the third-person perspective commonly found in non-clickbait headlines (Chakraborty et al. 2016).

A total of 1,630 articles from the three media outlets have been analyzed, as insidestory did not publish any content with the aforementioned characteristics. The components analyzed were clickbait headlines and references to the appearance of the social and personal life of Stefanos Kasselakis. The questions that guided the analysis were:

Does the title have clickbait characteristics in terms of word usage, image selections, etc?

Does it contain questions?

Does it contain references to Kasselakis’ personal and social life?

The presentation of the findings is organized across each medium so as to paint a clear picture of how the political economy of each medium and its orientation plays a significant role in the way it addresses issues.

4. Discussion

Before Kasselakis entered the race, his political opponent Achtsioglou had been the clear frontrunner to succeed former Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, who resigned following SYRIZA’s significant defeat in May’s 2023 elections.

Kasselakis was seen as emblematic of a “post-politics” era, as he ascended to the leadership without engaging in debates or interviews, instead relying on a continuous stream of social media posts featuring his American partner, his gym routines, his dog, and his coffee preferences.

His candidacy sidestepped the normal course of public discussion, using social media platforms to project, even create, a tailored image as he ran a campaign more akin to entertainment than politics, eschewing substance and meaning for the tools of a digital influencer.

Enlightening is the following event. On the night SYRIZA, Greece’s biggest left-wing party, voted for its new leader, Kasselakis’ team ordered pizzas. Kasselakis came down to the lobby with his partner, Tyler McBeth, to collect the pizzas in person. Later, he returned to hand out a few pizzas to the journalists. The pizza delivery story was at the top of Google search results for Kasselakis’ name. The incident is emblematic of his campaign, which catapulted him onto Greece’s political scene over a matter of weeks. He used a mastery of TikTok, Instagram, and X to create an unexpected buzz around his name and his personal life.

The election of Stefanos Kasselakis serves as an ideal case study for examining the prevalence of “viral journalism”. His candidacy and subsequent victory have attracted widespread attention and coverage, showcasing the dynamics of sensationalism within media discourse. By dissecting the media portrayal of Kasselakis through headlines and leads, we can illuminate the factors contributing to the proliferation of viral content in political reporting.

“Viral journalism” often focuses on topics that are timely, sensational, or emotionally compelling, as these tend to garner more attention and shares online. It relies heavily on catchy headlines, striking visuals, and content that evokes strong reactions from readers or viewers. The following section will present the analysis results of newspaper headlines and articles with the tag Stefanos Kasselakis.

Analysis of headlines of this period connected to Kasselakis, fulfill the criteria of emotional appeal, have powerful language and imagery, as well as engagement potential. Media organizations used it as a part of their strategy to catch readers through “a headline that does not respond to traditional journalistic criteria and whose ultimate goal is to keep the reader in the webpage for as long as possible, not to inform” (Orosa et al. 2017, p. 1265). This perspective defines headlines as “stylistic and narrative instruments that function as decoys to induce anticipation and curiosity in the reader so that they click on the headline and continue reading” (Blom and Hansen 2015, p. 87).

4.1. Proto Thema

“Proto Thema” is a Greek Sunday newspaper that was first published on 27 February 2005 and remains the Sunday newspaper with the largest circulation. In January 2008, the protothema.gr website was created as a daily online newspaper that provides coverage of a wide range of topics, including current events, politics, economics, culture, sports, and more.

Clickbait headlines appeared as the main style of writing on protothema.gr, published in September 2023. In this deluge, a special tag or section dedicated to Stefanos Kasselakis provided a spotlight for readers looking for further research into these statistics (see Figure 2). Designed to attract attention and drive clicks, these headlines used persuasive language and hyperbole to lure readers. Emotional shifts were evident in all articles, with writers using emotionally charged words to evoke strong reader responses. By tapping into reader sentiment, this content was designed to engage and encourage participation on social media. Speculation fueled intrigue and the writers teased out strange nuances of Stefanos Kasselakis’ personality. This uncertainty further fueled the click-chaos around his name, leading to intrigue and speculation about his identity and motivations. Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) emerged as the primary sources of approximately 900 articles. The sheer volume of content on these platforms increased the reach and impact of clickbait headlines and sensationalist stories. Algorithmic strategies that prioritized engagement fueled the proliferation of phenomenal stories, contributing to the saturation of Stefanos Kasselakis’ storytelling across digital channels.

Figure 2.

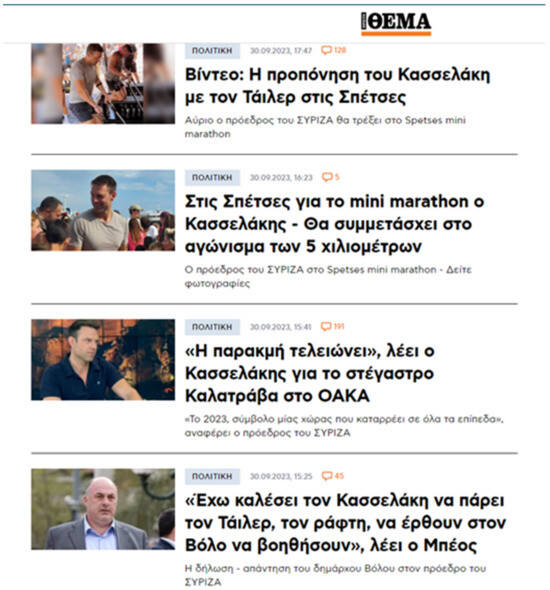

Screenshots of the protothema.gr section with the tag Stefanos Kasselakis.

Characteristic is the first title in Figure 3: “If Kasselakis looked like Quasimodo would we bother with him?” wrote Vicky Hatzivasiliou on Instagram. We all succumbed to beauty… racism” or the first title in Figure 4 “Video: Kasselakis’ training with Tyler in Spetses”. It becomes evident that Kasselakis’ portrayal hinges on superficial elements such as appearance. This tendency sheds light on a significant factor contributing to the proliferation of viral content in political reporting: the tendency to prioritize sensationalistic aspects over substantive issues. By scrutinizing how Kasselakis is judged based on his appearance or his gym routines, we can uncover the role of superficial narratives in driving the spread of viral content within political discourse.

Figure 3.

Screenshots of clickbait headlines of the protothema.gr for Stefanos Kasselakis.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of clickbait headlines of the protothema.gr for Stefanos Kasselakis.

4.2. iefimerida.gr

The iefimerida.gr is a Greek news website that was established in 2011, has high traffic, and is ranked among the top twenty Greek websites. According to data from the international organization Reuters Institute, in 2022, this website will have a 20% share of weekly traffic for all Greek users.

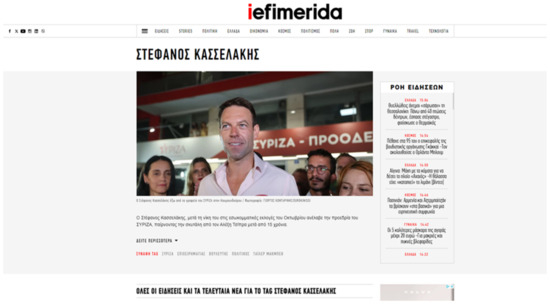

Continuing our analysis, we note that the second online platform we chose iefimerida.gr, presents similar characteristics to those mentioned above. Specifically, we also have here a large number of articles about or related to Stefanos Kasselakis, approximately 700 articles for the month of September 2023. In addition, in the special tag or category created for Stefanos Kasselakis, just before the articles, there is a short description of who he is and what his professional career has been so far (see Figure 5). Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) are the main sources of the articles, characterized by the proliferation of emotionally charged content and clickbait headlines with sensationalist language and exaggerated claims to captivate audience attention. It is worth mentioning that the content and the titles of these two media platforms (protothema.gr and iefimerida.gr) are very similar, to the extent that if you do not see which media is which, you can not practically distinguish them.

Figure 5.

Screenshots of clickbait headlines of iefimerida.gr section with the tag Stefanos Kasselakis.

We can read in the second headline of Figure 6, “The journalists were in a frenzy with Kasselakis because he treated them to a bagel”. Headlines like this, as Palau-Sampio notes, can also be associated with a certain type that “unlike the informative headline, appeals to curiosity with humor, emotion or classic baits like sex” (Palau-Sampio 2016, p. 68). Palau-Sampio puts this phenomenon in relation to infotainment and content trivialization, and associates it with the “viral strategies, developed in the field of marketing (…) an important resource when feeding digital traffic, and the ability of new media to capture advertising” (Palau-Sampio 2016, p. 67). We also have the headline “Kasselakis responds to a homophobic comment” in Figure 7, which again points to Kasselakis’ sexual orientation.

Figure 6.

Screenshots of clickbait headlines of the iefimerida.gr for Stefanos Kasselakis.

Figure 7.

Screenshots of clickbait headlines of the iefimerida.gr for Stefanos Kasselakis.

It is clear that there is no in-depth analysis of the events but a simple reproduction of statements and comments made on social media. Several times, it was observed the phenomenon that the name Stefanos Kasselakis is mentioned in the title, but, in fact, the content of the article does not refer to or directly concern him, and this proves once again the pursuit of clicks and high engagement rate. After all, it is quite common in today’s digital landscape for many news organizations to find themselves in a challenging situation, torn between adhering to online trends to attract public attention and make a profit, while maintaining their reputation as trustworthy news sources (Silverman 2015).

4.3. The Press Project

thepressproject.gr (TPP) was founded in 2010 and is a Greek independent digital media outlet that relies exclusively on the subscriptions of its readers. It is known for its in-depth investigative journalism and analysis on various topics, including politics, economics, society, and international affairs. It has received recognition both domestically and internationally for its journalistic work and contribution to public discourse.

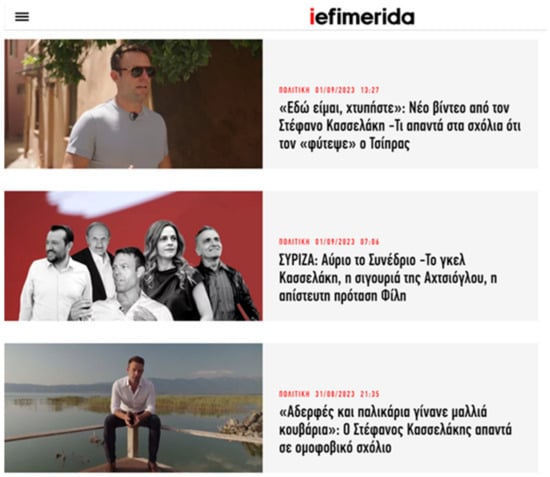

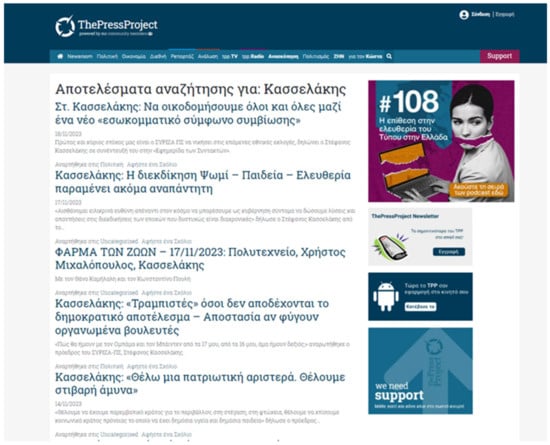

In contrast to the first two online media we studied, thepressproject.gr for the corresponding period of time, devoted only 30 articles to Stefanos Kasselakis and all the discussion that was provoked in the media about his upcoming candidacy as party president, that is as many articles were uploaded daily to protothema.gr and iefimerida.gr (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Screenshot of the search results of thepressproject.gr about Stefanos Kasselakis.

In comparison to the sophisticated clickbait headlines of the period, the articles analyzed for thepressproject.gr adopted a neutral tone in their headlines as shown in Figure 9. These articles prioritized the important over the emotional, with the goal of providing readers with accurate and balanced information. By avoiding emotional metaphors, they fostered an environment conducive to critical thinking and informed discourse, focused on a variety of factors to highlight the content and give readers a broader perspective.

Figure 9.

Screenshots of headlines of thepressproject.gr for Stefanos Kasselakis.

4.4. Inside Story

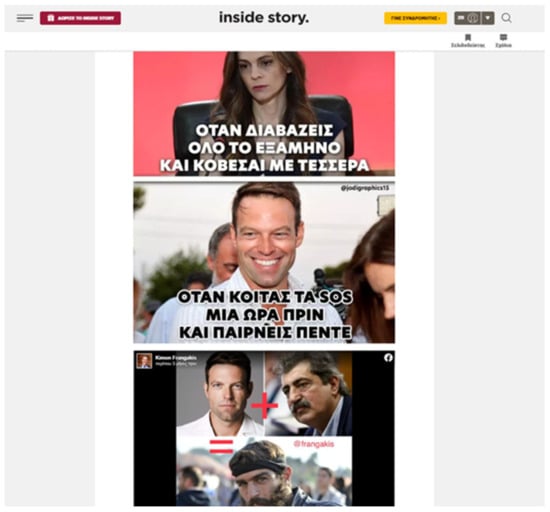

The site insidestory.gr was founded in 2016 and is a daily subscription media outlet offering independent, investigative, in-depth journalism on a wide range of topics. It has completed and published a Transparency Report by participating in the Journalism Trust Initiative (JTI) and has been awarded EUR 25,000 from the European Journalism COVID-19 Support Fund to support the operation of its core team and its strong network of journalists in the difficulties created by the crisis, as well as to cover part of the cost of maintaining an active dialogue with its readers and subscribers.

Unlike the other three online media, the results we found were completely different when we did the relevant search with the name Stefanos Kasselakis for the same period (September 2023). There was no specific category with articles about Stefanos Kasselakis and the current news about the election. Instead, the results led us to a special category with humorous content through which the person of Stefanos Kasselakis was commented on (see Figure 10). More specifically, this category contained memes whose content criticized the current political situation and what was being discussed about Stefanos Kasselakis and his candidacy as shown in Figure 11. Essentially, it was a reproduction of memes that had been published on other online platforms with small humorous captions—comments.

Figure 10.

Screenshot of the search results of insidestory.gr about Stefanos Kasselakis.

Figure 11.

Screenshot of the special category with memes of insidestory.gr about Stefanos Kasselakis.

The way they chose to approach this person and the prevailing situation around it reinforces the profile of this online medium and the way it operates. After all, they themselves state this clearly within their website: “Here you won’t find the news you read elsewhere. We don’t focus on the news of the day. You can get that for free” accessed on 7 April 2024).

The insidestory.gr is an online journalistic medium dedicated to investigative journalism with international methods and ethical standards. It does not deal with current affairs, but with in-depth research on new and unexpected issues, aiming to present the story behind the news in order to expose its implications, to understand the connections, and ultimately, to be able to understand what is happening. Therefore, the audience it addresses is specific, seeking meaningful and quality journalism on issues that concern them, and they believe that they will be able to understand them better and in-depth. As Himma-Kadakas and Kõuts (2015) mentioned, consumers’ main reasons for paying for online news content include anticipating high-quality and distinctive web content.

5. Conclusions

In summary, Kasselakis’ case study reveals factors that greatly affect the nature and quality of information disseminated to the public. The emergence of homogeneity highlights a troubling limitation in the concepts presented, preventing a full understanding of complex issues. This limitation is exacerbated by the relationship between social media and traditional media structures, and online platforms often promote certain issues, potentially to the detriment of others.

6. Key Findings

The findings have not been surprising considering the type of outlets studied and their characteristics. On the one hand, “viral journalism” offers a good way to earn as a news medium for advertising, while on the other hand, if you are looking for loyal readers, then one needs to invest more on credibility. In the hunt for sustainable business models, publishers have to answer the question of ad-based or subscription-based media business models, which is a key one, and accordingly design their content strategy. The most important findings from our analysis are two:

The revenue models seem to be an important factor for “virality”. When they pay for the content, readers expect high quality. So, the content has to meet the expectations of the reader. From our analysis, it became evident that the only outlet with a subscription in our sample (insidestory.gr) did not contain any stories that fit the description “viral journalism”. The more news media outlets switch from an advertisement-driven revenue model to a subscriber-driven revenue model, the less “viral journalism” will play an important role in news work.

“Viral” journalism techniques mainly concern the headlines. Therefore the headlines are made as attractive as possible. Additionally, there has been a sharp decline in in-depth analysis in news articles that look at clicks and traffic in the digital realm. Prioritizing emotion and conciseness over critical analysis compromises the integrity and credibility of the information presented to the audience. This trend not only undermines the public’s access to minority opinions but also undermines trust in media organizations. On the other hand, the consideration of target audiences in content production highlights the professional importance of journalism. Tailoring content to the preferences and expectations of a particular demographic can sustain one narrative while marginalizing others, thereby shaping public discourse in predetermined ways.

Furthermore, we can assume that the orientation of news organizations plays an important role in news production, as biases and norms within these organizations influence editorial decisions. These biases can distort information delivery, impose strengthening pre-existing beliefs and ideas, and ignore the use of new ideas. As Silverman (2015) mentioned, certain content labeled as “viral” does not become truly viral until news websites choose to promote it. Also, the influence of different sources of income on news content cannot be ignored. Financial support from institutions can introduce biases and conflicts of interest into editorial decisions, potentially undermining the integrity and objectivity of journalists. Thus, media organizations face a dilemma between adhering to online trends to sustain profitability and upholding high standards to preserve credibility as news sources (Silverman 2015).

In conclusion, a full understanding of media content production requires an analytical examination of the complexities at play. By scrutinizing the impact of product uniformity, social media trends, lack of in-depth research, lack of media channels, target audience perceptions, and revenue streams participants can better understand the modern media ecosystem and the diverse, informative, and reliable media environment.

In a world where the digital landscape dominates the media landscape, there is a need to come up with strategies to bridge the gap between “quality journalism” and “viral journalism”. We discuss ways for news organizations, journalists, and consumers to make healthy choices, promote responsible reporting, and combat the pitfalls of emotion. Recommendations should include a call for transparent sources of information, media literacy for consumers, and the importance of critical thinking in times of information overload. Encouraging responsible sharing on social media and supporting quality independent journalism organizations are also integral parts of this section.

To better understand the implications of this research, future studies should investigate whether the results are applicable to different countries and focus more on business strategies and their link to content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and Z.P.; Methodology, I.K. and Z.P.; Writing—original draft, Z.P.; Writing—review & editing, I.K. and Z.P.; Supervision, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Rawi, Ahmed. 2019. Viral news on social media. Digital Journalism 7: 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Chris W. 2011. Between creative and quantified audiences: Web metrics and changing patterns of newswork in local US newsrooms. Journalism 12: 550–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, Philipp, Mark Eisenegger, and Diana Ingenhoff. 2022. Defining and measuring news media quality: Comparing the content perspective and the audience perspective. The International Journal of Press/Politics 27: 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaco, Ángela, Marta Redondo, and Pilar Sánchez-García. 2019. Clickbait as a strategy of viral journalism: Conceptualisation and methods. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 74: 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebić, Domagoj, and Marija Volarević. 2016. Viral journalism: The rise of a new form. Medijska Istraživanja: Znanstveno-Stručni Časopis za Novinarstvo i Medije 22: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berger, Jonah, and Katherine L. Milkman. 2013. Emotion and virality: What makes online content go viral? NIM Marketing Intelligence Review 5: 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, Jonas Nygaard, and Kenneth Reinecke Hansen. 2015. Click bait: Forward-reference as lure in online news headlines. Journal of Pragmatics 76: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczkowski, Pablo J. 2005. Digitizing the News: Innovation in Online Newspapers. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boczkowski, Pablo J. 2009. Technology, monitoring, and imitation in contemporary news work. Communication, Culture & Critique 2: 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Boczkowski, Pablo J., Eugenia Mitchelstein, and Mora Matassi. 2018. “News comes across when I’m in a moment of leisure”: Understanding the practices of incidental news consumption on social media. New Media & Society 20: 3523–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart, Leo. 2004. Reflections on content quality in newspapers. Newspaper Research Journal 25: 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bransford, John D., and Marcia K. Johnson. 1972. Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 11: 717–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, Abhijnan, Bhargavi Paranjape, Sourya Kakarla, and Niloy Ganguly. 2016. Stop clickbait: Detecting and preventing clickbaits in online news media. Paper presented at 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), Davis, CA, USA, August 18–21; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Elisia L. 2002. Online journalism as market-driven journalism. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 46: 532–48. [Google Scholar]

- de la Piscina Martínez, Txema Ramirez, María Gorosarri González, Alazne Aiestaran Yarza, Beatriz Zabalondo Loidi, and Antxoka Agirre Maiora. 2014. Periodismo de calidad en tiempos de crisis: Un análisis de la evolución de la prensa europea de referencia (2001–2012). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 3: 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisova, Anastasia. 2016. Memes, Not Her Health, Could Cost Hillary Clinton the US Presidential Race. The Independent, September 12. [Google Scholar]

- Denisova, Anastasia. 2023. Viral journalism. Strategy, tactics and limitations of the fast spread of content on social media: Case study of the United Kingdom quality publications. Journalism 24: 1919–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, James, and Susana Sampaio-Dias. 2021. “Tell the Story as You’d Tell It to Your Friends in a Pub”: Emotional Storytelling in Election Reporting by BuzzFeed News and Vice News. Journalism Studies 22: 1608–26. [Google Scholar]

- Deuze, Mark. 2004. What is multimedia journalism? Journalism Studies 5: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dor, Daniel. 2003. On newspaper headlines as relevance optimizers. Journal of Pragmatics 35: 695–721. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Conill, Raul, and Edson C. Tandoc, Jr. 2018. The audience-oriented editor: Making sense of the audience in the newsroom. Digital Journalism 6: 436–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himma-Kadakas, Marju, and Ragne Kõuts. 2015. Who is willing to pay for online journalistic content? Media and Communication 3: 106–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifantidou, Elly. 2009. Newspaper headlines and relevance: Ad hoc concepts in ad hoc contexts. Journal of Pragmatics 41: 699–720. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Elihu. 1957. The two-step-flow of communication. An up-to-date report on a hypothesis. Public Opinion Quarterly 21: 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Sawinder, Parteek Kumar, and Ponnurangam Kumaraguru. 2020. Detecting clickbaits using two-phase hybrid CNN-LSTM biterm model. Expert Systems with Applications 151: 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, Bill, and Tom Rosenstiel. 2014. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York: Three Rivers Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, Stephen, and Tom Rosenstiel. 2015. Defining and Measuring Quality Journalism. New Brunswick: Rutgers School of Communication and Information. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, Paul F., Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet. 1944. The People’s Choice. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, John H. 1994. Market-Driven Journalism: Let the Citizen Beware? Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Market-Driven-Journalism-Let-Citizen-Beware/dp/0803952538 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- McQuail, Denis. 1992. Media Performance: Mass Communication and the Public Interest. Available online: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/media-performance/book202974 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- McQuail, Denis. 2005. McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory, 5th ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, Klaus, Jonas Schützeneder, José Alberto García Avilés, José María Valero-Pastor, Andy Kaltenbrunner, Renée Lugschitz, Colin Porlezza, Giulia Ferri, Vinzenz Wyss, and Micro Saner. 2022. Examining the Most Relevant Journalism Innovations: A Comparative Analysis of Five European Countries from 2010 to 2020. Journal Media 3: 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, Irene Costera. 2001. The public quality of popular journalism: Developing a normative framework. Journalism Studies 2: 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Adam. 2012. Virality in Social Media: The SPIN Framework. Journal of Public Affairs 12: 162–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchelstein, Eugenia, Pablo J. Boczkowski, Keren Tenenboim-Weinblatt, Kaori Hayashi, Mikko Villi, and Neta Kligler-Vilenchik. 2020. Incidentality on a continuum: A comparative conceptualization of incidental news consumption. Journalism 21: 1136–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahon, Karine, and Jeff Hemsley. 2013. Going Viral. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Nic. 2024. Journalism, Media and Technology Trends and Predictions 2024. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Orosa, Berta García, Santiago Gallur Santorum, and Xosé López García. 2017. El uso del clickbait en cibermedios de los 28 países de la Unión Europea. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 72: 1261–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau-Sampio, Dolors. 2016. Reference press metamorphosis in the digital context: Clickbait and tabloid strategies in Elpais.com. Communication & Society 29: 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik, John V. 2001. Journalism and New Media. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, Joseph, Regina Lewis, Lynne Mobilio, David Perry, and Niranjan Raman. 2004. Viral Marketing or Electronic Word-of-Mouth Advertising: Examining Consumer Responses and Motivations to Pass along Email. Journal of Advertising Research 44: 333–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, Robert G. 2000. Measuring Media Content, Quality, and Diversity. Turku: Turku School of Economics and Business Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez de la Piscina, Txema, Maria Gonzalez Gorosarri, Alazne Aiestaran, Beatriz Zabalondo, and Antxoka Agirre. 2015. Differences between the quality of the printed version and online editions of the European reference press. Journalism 16: 768–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, Craig. 2015. Lies, Damn Lies, and Viral Content. Available online: https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/craig_silverman_lies_damn_lies_viral_content.php (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Steensen, Steen. 2009. What’s stopping them? Towards a grounded theory of innovation in online journalism. Journalism Studies 10: 821–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson C., Jr., and Joy Jenkins. 2017. The Buzzfeedication of journalism? How traditional news organizations are talking about a new entrant to the journalistic field will surprise you! Journalism 18: 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson C., Jr., and Ryan J. Thomas. 2015. The ethics of web analytics: Implications of using audience metrics in news construction. Digital Journalism 3: 243–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touri, Maria, Sophia Theodosiadou, and Ioanna Kostarella. 2017. The internet’s transformative power on journalism culture in Greece: Looking beyond universal professional values. Digital Journalism 5: 233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, Juliane, and Wolfgang Schweiger. 2014. News quality from the recipients’ perspective: Investigating recipients’ ability to judge the normative quality of news. Journalism Studies 15: 821–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriani, Augusto, and Cristian Vaccari. 2016. Accidental exposure to politics on social media as online participation equalizer in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. New Media & Society 18: 1857–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vehkoo, Johanna. 2010. What Is Quality Journalism and How It Can Be Saved. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, pp. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).