Abstract

The Rohingya crisis has been a significant issue for national and international news media, capturing their attention for an extended period and documenting various phases of the crisis. Previous research exploring the tones and portrayal of the Rohingyas in the news lacks comparative and temporal analysis of news sentiments. In this study, we aim to fill this gap by analyzing 8074 news stories on Rohingya issues published in 10 news media outlets from 10 countries between 2009 and 2023. Our computational sentiment analysis reveals that Rohingya-related news sentiments are predominantly negative and fluctuate over the years across different countries, showing little identifiable patterns. An ANOVA suggests significant variation in news sentiments among countries, with some countries exhibiting more similar sentiments than others, thus creating distinguishable groups. Some of our findings contradict previous scholarships, warranting further research and novel frameworks. Additionally, we encourage scrutiny of academic insights to address potential biases against news media’s journalistic integrity.

1. Introduction

The Rohingya crisis has been a crucial issue for national and international news media, not only for its impacts and multitudes but also for intervening and multifaced topics covered in the news articles (Irom et al. 2022; Kironska and Peng 2021; Ubayasiri 2019; Vu and Lynn 2020; Wani 2022). This crisis has been grabbing the news media’s attention for a long time, documenting the different phases of the crisis and circulating their own set of agendas. Moreover, the news media and their respective countries may have their own guidelines and concerns regarding Rohingya displacement, which might be reflected in news articles (Ehmer and Kothari 2021; Kironska and Peng 2021; R. Lee 2019). On these grounds, it is expected that the published news articles might produce varied sentiments, where including a wide range of temporality and diversified geolocation might contribute a different dimension to this analysis. However, the integrated insights of the temporal, regional, and political aspects of the Rohingya crisis are absent in previous academic scholarship. Against this backdrop, considering the intensity of the topic of the news articles and the underlying dimensions that those news articles carry, we focused on sentiment analysis of Rohingya news to understand the chronological and geographical portrayal of Rohingyas through computational and statistical methods. We used existing journalism and media studies theories to assess their relevance and uncover the underlying insights. Using computational methods in comparative media analysis is a novel approach in journalism studies.

Our findings suggest varying degrees of negative sentiments in Rohingya news, while some countries have common tones in news coverage. We hope that the insightful findings from the sentiment analysis of Rohingya-related news articles will enrich academic discussions and broaden the scope of research in Rohingya and media studies. Additionally, our findings call for the development of existing frameworks. This research not only contributes theoretically and methodologically but also offers valuable insights into a pressing humanitarian crisis. In the next section, we reviewed news sentiments towards refugees, specifically focusing on the Rohingyas.

2. Sentiments Toward Refugees

Sentiment analysis is a method used to understand attitudes, feelings, and opinions from textual or multimodal data. Technically speaking, it is a cutting-edge method for recognizing and classifying sentiments and emotions conveyed in different forms of human communication, mostly textual (Tan et al. 2023). Cui et al. (2023) defined sentiment analysis as one of the most common text-based analytical methods for extracting people’s attitudes, emotions, assessments, and views regarding issues, entities, subjects, events, and items. They highlighted its utility in enabling policymakers, company owners, and service providers to make better decisions. Bordoloi and Biswas (2023) pointed out that sentiment analysis performs many functions, such as retrieving sentimental details, analyzing opinionative and sentimental online data, and classifying sentimental patterns in various contexts.

Many studies have applied sentiment analysis techniques to understand public perceptions of migrated or displaced refugees by analyzing various textual data, such as newspapers, blogs, and social media texts. Sentiment analyses of mainstream and social media texts on refugees have revealed different attitudes across countries. Some studies have shown that sentiments towards refugees vary from country to country, from positive to negative, and from traditional media to social media, reflecting the respective public perceptions.

Based on a collection of tweets published in Swedish from 2012 to 2019, Kopacheva and Yantseva (2022) examined sentiment polarization over time and in the context of the European refugee crisis. They noted a shift in the tone of users’ messages, observing “a certain move towards the negative and more extreme end of the polarity spectrum” (p. 23). Pope and Griffith (Pope and Griffith 2016) also found higher negative sentiments targeted toward refugees. They conducted a sentiment analysis to understand the refugee crisis in Europe better using Twitter content written in English and German and published over 68 days. Their findings revealed that tweets about the refugee crisis exhibited higher negative and lower positive emotions than their model’s average.

Backfried and Shalunts (2016) found similar attitudes in social media texts but different results in traditional media. They conducted a sentiment analysis covering the humanitarian crisis of refugees in Europe, collecting 48,733 articles from traditional media and 16,593 tweets, posts, and comments from social media texts originating from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland between October 2015 and March 2016. They discovered that traditional media carried more neutral content, while social media showed a decline in positive posts.

Some studies compared news and social media sentiments across religious traditions. Chan et al. (2020) conducted a multilingual human-validated sentiment analysis of over 560,000 news articles from 37 online news outlets in four Christian-majority countries (the US, Australia, Germany, and Switzerland) and two Muslim-majority countries (Lebanon and Turkey). They found that coverage of refugees without mentioning terrorists, Muslims, or Islam resulted in the lowest fear and highest empathy levels in Christian countries. However, when refugee coverage included these terms, fear increased while pity declined. This pattern is largely absent in the news from Muslim countries.

Öztürk and Ayvaz (2018) analyzed 2,381,297 tweets in Turkish and English to investigate popular attitudes and sentiments concerning the Syrian refugee situation. They found that the Turkish-speaking community shared more positive tweets about refugees than the English-speaking population. The overall sentiment score of Turkish tweets was slightly more positive (35%) than negative (34%), with neutral sentiment (31%) falling between the two. Conversely, the English-speaking community’s tweets exhibited more neutral or unfavorable stances, generating fewer positive sentiments (12%).

Many studies have documented that real-world events surrounding the refugee crisis significantly impact public perceptions and sentiments, suggesting that the sentiment patterns and event occurrences are inextricably linked (Backfried and Shalunts 2016). Öztürk and Ayvaz (2018) revealed that opinions expressed in Turkish tweets shifted over time due to external events, such as the Syrian government’s chemical gas assault and the US airstrike in response. Hussain et al. (2018) performed a sentiment analysis on blogs published between January 2015 and March 2016 to examine changes in narratives toward refugees during the European migration crisis. They found that the overall sentiment was mostly positive from May to July 2015 and neutral from January to October 2015, with a flip from positive to negative after October 2015. They observed that mainstream media’s overall attitude toward migrants was positive. Following the Paris attacks in November 2015 and the assaults on German women in January 2016, citizens in numerous European countries shifted from sympathetic to severe sentiments. Pope and Griffith (Pope and Griffith 2016) also noted that terrorist incidents in Paris and Cologne significantly impacted online Twitter sentiment about the refugee crisis.

According to past studies, the prevailing sentiment in traditional media appears neutral in many countries, whereas social media is dominated by negative sentiment. Additionally, differing sentiments exist across religious traditions. Studies have also identified that sentiment patterns and values vary depending on nationalistic stances and reflections on real-world events. While these findings offer general perspectives on refugees, understanding how people perceive the Rohingya crisis is essential for this study’s purpose.

2.1. Sentiments Toward the Rohingyas

Rohingya-related sentiment analysis is largely scarce, limiting our understanding of this topic and leaving a scholarly gap. Among the few studies, Das et al. (2022) combined opinion mining with sentiment analysis and conducted an NLP-based study on the Rohingya crisis using a relatively smaller dataset of social media texts, manually collected user comments, and attempted to detect the sentiment related to the Rohingya community. They found that most Bangladeshis did not view the refugee situation positively.

Similar to social media reactions, Rohingyas were also negatively portrayed in mainstream media coverage. Ehmer and Kothari (2021) analyzed a hundred news stories from a Malaysian newspaper, revealing that Rohingya refugees were portrayed as violent, criminal, and illegal outsiders. This article highlighted the stereotypical representations of Rohingyas, portraying them as a threat to the host country’s population. Wani’s (2022) study based on an Indian English newspaper yielded similar results, portraying the Rohingya as alien and enemy. A Myanmar-based study by Kironska and Peng (2021) showed how the Rohingyas were framed as responsible for violence and as a national security threat. Similarly, R. Lee (2019) revealed that news media produced anti-Rohingya rhetoric and intensified violent narratives about the Rohingya community.

Multi-country news analyses provide a broader scope to view the Rohingya crisis from a more distinct and contrastive perspective. In a comparative analysis of the coverage of Indian and Chinese newspapers regarding the Rohingya and related concerns, Rhaman (2023) conducted a text-based study showing the disparities between the media depictions of the two countries. This study investigated how the media shapes and frames public perception and government policy around the Rohingya crisis by analyzing Chinese and Indian news headlines. Vu and Lynn (2020) examined news reports on the Rohingya crisis from Bangladesh, the US, and Myanmar, identifying several recurring themes such as violence, crisis solutions, and repatriation concerns. Similarly, Irom et al. (2022) evaluated over 500 news articles published in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Canada, and the US to identify important news frames, refugee characteristics, and published stories. Their findings were intriguing—there were few or no variations in using frames, sources, and refugee descriptions. Abbas (2024) analyzed news data from four countries, Myanmar, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and China, to show how Rohingya Muslims are portrayed, demonstrating each country used positive-self and negative-other frameworks in their news coverage.

2.2. Comparative News Sentiments: Toward a Conceptual Framework

Among the available frameworks in journalism and media studies scholarship, the Comparative Media Systems theory proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2004) is an option for scholars for multi-country analysis of media functions (e.g., social responsibility) and outputs (e.g., news reports) (Hardy 2012). This theory explains three major models of global media systems, Liberal, Democratic Corporatist, and Polarized Pluralist, from two dimensions: media and political systems. Four factors influence a country’s media system as follows: the structure of the media market, political parallelism, journalists’ professionalism, and state intervention (Hallin and Mancini 2004; Mancini 2010). The Liberal Model features lower political control over the media, the media’s market orientation, and journalistic professionalism, which is observed in most liberal democracies like Canada and the US. The Democratic Corporatist Model shares some features of the Liberal Model but proposes the coexistence of press freedom and state intervention. In countries like Germany and Sweden, the government considers the media as a social institution for which the state should be responsible, with subsidies and certain regulations. According to the Polarized Pluralist Model, the media systems in countries like Spain and Portugal suffer from increased political intervention and weaker journalistic professionalism, among others (Hallin 2016; Hallin and Mancini 2004; Hardy 2012; Hepp and Couldry 2009).

Although scholars claim this theory has broader applicability (Hardy 2012; Hepp and Couldry 2009; Mancini 2010), its West-centric roots question its validity in non-Western contexts, especially when it comes to mixed regional and political systems. It resembles the issues with the Normative Theory or Four Theories of the Press proposed by Siebert et al. (1956), which consists of Authoritarian, Liberal, Social Responsibility, and Soviet Theories, to explain the global media systems. Scholars criticized this theory as well for its political origin in the wake of the Cold War and problematic historical and theoretical understanding of the multifaceted and complex global media systems (Ostini and Ostini 2002; Vaca-Baqueiro 2018). Researchers believe the existing frameworks offer limited applicability in today’s changing comparative media systems, and no novel framework is available either (Nerone 2018). We used these theories as a conceptual lens to observe their explainability of news sentiments toward the Rohingya crisis, specifically with temporality and in mixed regional and political contexts.

3. Research Questions

This review of previous literature suggests at least three major gaps. First, the sentiment analysis of media reports on the Rohingya crisis is limited. While some studies manually attempted to decode audience sentiments, more reliable automated sentiment analysis of news reports is absent. Second, large-scale data and multi-country sentiment insights on the Rohingya crisis are missing. Similar studies have focused mostly on European refugee crises and countries, excluding long-standing crises like the Rohingya and regional variations in crisis attitudes. Third, the evolution of attitudes toward Rohingyas has been overlooked. Few studies have provided temporal variations in attitudes toward refugees but failed to incorporate the Rohingyas. Therefore, to address these existing theoretical and methodological gaps, we asked two questions:

RQ1: How have Rohingya news sentiments evolved in different countries?

RQ2: Are there any significant differences in news sentiments among the countries?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source

This study investigated media coverage of Rohingya issues by analyzing news media data. We purposively selected ten news media from ten countries based on their significant connection to the crisis (see Table 1). Our selection process had two steps.

Table 1.

Descriptions of the data.

In the first step, we selected the countries. We initially focused on host countries and those with political significance, such as China, the UK, and the US, which are global superpowers often engaged in international humanitarian efforts. China, for example, may have strategic interests in Myanmar and could influence diplomatic discussions or resolutions. According to the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO), Bangladesh hosts the most Rohingyas, followed by Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Malaysia, and India (Alam 2019). The US hosts a few thousand Rohingyas and is politically involved as a superpower, like China. Turkey has consistently expressed concerns and provided aid since the crisis began. The UK and Qatar, representing Europe and the MENA region, respectively, have influential news outlets like The Guardian and Al Jazeera. Qatar is also active in international diplomacy and supports the Rohingyas.

The list highlights countries’ religious affiliations and regional differences. For instance, Bangladesh and Pakistan are predominantly Muslim, unlike the UK and USA. Bangladesh, Malaysia, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey are members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), which aims to strengthen cooperation among Islamic states and protect their interests (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2022). Given that the Rohingyas are Muslims and religion significantly impacts the crisis and global politics, we aimed to observe variations in coverage across different religious traditions.

Unlike previous studies (e.g., Kanaker et al. 2020; Ubayasiri 2019; Vu and Lynn 2020), we aimed for a balanced representation of regions and religions to gain comprehensive insights. These categories are not mutually exclusive: some host countries like India are also politically influential. Similarly, politically important countries like the US also host Rohingyas. Our country selection was based on a combination of relevant factors mentioned earlier. However, we had to exclude some significant countries, such as Russia, due to the limited coverage of the Rohingya issue in their media.

In the next step, we selected the online versions of ten news media from the chosen countries (see Table 1). We considered media popularity, consistent topic coverage, website structure, and language. First, we assessed the popularity based on reputation and traffic (SCImago Media 2024). Using our criteria, we identified popular outlets such as The Daily Star and The Star. Second, we used pre-determined keywords to find relevant news on these websites. Some popular sites, like Hindustan Times and The Dawn, lacked sufficient and continuous coverage compared to The Times of India and Express Tribune, so we had to exclude them. Third, website structure (Document Object Model (DOM)) sometimes hindered data scraping. For instance, Arab News in Saudi Arabia was difficult to scrape, so we chose Saudi Gazette instead. Lastly, we selected only English news portals to facilitate reliable comparative analysis, overcome our language limitations (the authors are familiar with English), and follow previous research standards (e.g., Irom et al. (2022) and Vu and Lynn (2020)). All selected countries have established, popular, and reputable English news media.

4.2. Data Collection and Processing

We developed news portal scrapers utilizing Python’s Newspaper4k (https://newspaper4k.readthedocs.io, accessed on 24 April 2024) library (version 0.9.3.1). Newspaper4k specializes in scraping online news websites, including subscription-only ones like The New York Times. Initially, we created ten scripts corresponding to ten selected news websites and obtained raw data stored in ten MS Excel files. In our quest for Rohingya-related news stories, we employed two methods. Firstly, we prioritized news items labeled with dedicated “Rohingya” or related tags, facilitating easier identification of relevant news items under a single label. Many news portals, such as The Daily Star and The Times of India, archived Rohingya-related news stories with tags. However, certain news portals like The New York Times lacked such tags, prompting us to resort to our second method: keyword search. We extensively used three keywords for news retrieval: “Rohingya,” “Rohingya crisis”, and “Rohingya refugees”. We meticulously reviewed the scraped data (mainly the data scraped using the keyword search, which had higher possibilities of junk data) to identify irrelevant news items (n = 346), which we removed to ensure data validity.

Subsequently, we cleaned data on each file, eliminating duplicates, blank cells, and non-news elements such as links and extraneous text. Additionally, we standardized the date–time format across all entries to maintain consistency for the final analysis. Furthermore, we aggregated all data into a single file, sorting the news items according to their countries. The initial count of news items stood at 8074 (before duplicate removal), averaging 807.4 news items per country (see Table 1).

4.3. Data Analysis

Following the preparation of the main dataset, we developed an additional Python script. We utilized Polyglot (https://polyglot.readthedocs.io, 25 April 2024), a Python library for NLP, to conduct sentiment analysis of news articles, addressing RQ1. Our unit of analysis was each article. We augmented the main dataset with two additional columns containing sentiment scores ranging from −1 to 1 and three sentiment categories—positive, neutral, and negative (AlAgha 2021; Nandwani and Verma 2021). Polyglot offers polarity lexicons for 136 languages, including English. The word polarity scale was composed of three degrees: +1 for positive words, −1 for negative words, and 0 for neutral words. We used each news article as the unit of analysis. Subsequently, we generated a heatmap using Seaborn (https://seaborn.pydata.org, 25 April 2024), another Python library specializing in data visualization. For the heatmap, we utilized yearly mean values of sentiment scores. We complemented our automated insights with a manual close reading of the news text to gain a reliable and in-depth understanding of the context. To address RQ2, we employed an ANOVA with sequential Bonferroni post hoc test with yearly mean sentiment scores of the sampled countries to see if there were significant differences in news sentiments and their pairwise interrelationships. Note that not all countries had sentiment scores for all years, leading to some missing values. In such cases, we calculated the median sentiment scores of the respective countries, which is a common statistical imputation method (Zhang 2016). We added a network graph to extend and explain the findings of RQ2, produced using Flourish (https://flourish.studio, 27 April 2024), a data visualization tool listed in Google’s Journalist Studio and used by newsrooms globally.

5. Findings

5.1. Evolving News Sentiments

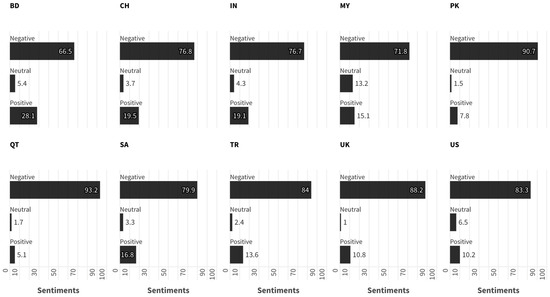

Our sentiment analysis, which included positive, neutral, and negative categories, revealed a predominance of negative sentiments across the media coverage of Rohingyas in the selected countries. The percentages of three sentiments within each country showed that Bangladesh, India, and China maintained a better balance of positive and negative news sentiments in the news (see Figure 1). In contrast, news in Qatar, Pakistan, the UK, and the US contained higher negative sentiments. Malaysia published more news stories with neutral sentiments than other countries.

Figure 1.

Percentages of different sentiments across countries. The acronyms of the countries are used in the figure: Bangladesh → BD, China → CH, India → IN, Malaysia → MY, Pakistan → PK, Qatar → QT, Saudi Arabia → SA, Turkey → TR, United Kingdom → UK, United States → US.

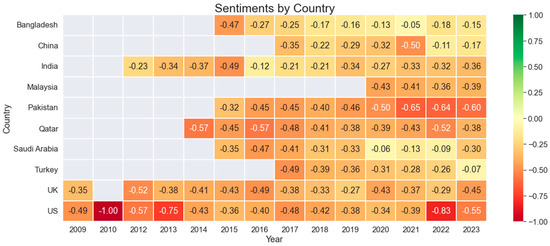

Over the years, mean sentiment values consistently leaned toward the negative spectrum across all countries (see Figure 2). Notably, Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey exhibited relatively higher proportions of lower negative sentiment than Pakistan, Qatar, the UK, and the US, which consistently portrayed higher negative sentiments in their news coverage. Particularly, the US maintained yearly consistency of higher negative sentiment throughout the study period, with the highest mean negative sentiment score and variation (M = −0.53, SD = 0.2). However, the mean sentiment scores in Pakistan and Qatar were also higher but with limited variation, indicating their concentrated sentiments and consistency in their higher negative sentiments (see Table 2).

Figure 2.

Yearly sentiment scores categorized by countries, depicting positive, neutral, and negative sentiments. Scores are distributed as follows: positive (0 to 1), neutral (0), and negative (−1 to 0).

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of each country’s news sentiment.

Certain countries showed visible fluctuations in sentiment over time (Figure 2). For instance, sentiment trends shifted from higher to lower negative sentiments in recent years, since 2020, for Saudi Arabia and Turkey, while India experienced a shift to lower negative sentiments in the mid-years, from 2016 to 2018, before dropping the scores again in the subsequent years. Sentiment patterns in China showed somewhat similar trends, with higher negative sentiments in 2017, 2020, and 2021 and lower negative sentiments in 2022 and 2022. Pakistan saw a notable change from lower negative to higher negative sentiments since 2015.

5.2. Variations in News Sentiments

The analysis of sentiment scores across multiple countries revealed variations in the portrayal of news articles. A one-factor ANOVA (Table 3) showed a significant difference between the categorical and dependent variables (F = 17.46, p ≤ 0.001). We calculated the effect size partial Eta squared, η2p = 0.57, which is large. According to Cohen (1988), the limits for the size of the effect are 0.01 (small effect), 0.06 (medium effect), and 0.14 (large effect). The findings underscore substantial differences in sentiment scores among the countries studied.

Table 3.

ANOVA of the countries’ mean sentiment scores.

A sequential Bonferroni post hoc test was used to compare the groups in pairs to determine which was significantly different, with 23 out of 45 pairs showing significance (Table 4). The test revealed that the pairwise group comparisons of Bangladesh–Pakistan, Bangladesh–Qatar, Bangladesh–UK, Bangladesh–US, China–Pakistan, China–Qatar, China–UK, China–US, India–Malaysia, India–Pakistan, India–US, Malaysia–Pakistan, Malaysia–Qatar, Malaysia–UK, Malaysia–US, Pakistan–Saudi Arabia, Pakistan–Turkey, Qatar–Saudi Arabia, Qatar–Turkey, Saudi Arabia–UK, Saudi Arabia–US, Turkey–UK, and Turkey–US had p-values less than 0.05. Thus, based on the available data, it can be assumed that these groups are each significantly different pairwise, meaning news sentiments significantly differ in the two countries of each pair. The remaining pairs had similarities in news sentiments.

Table 4.

Bonferroni post hoc test of pairwise group comparisons.

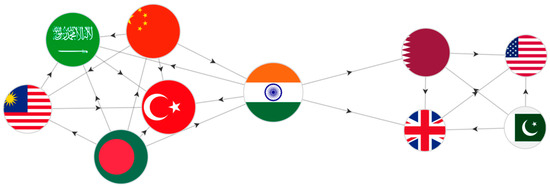

In a network analysis, we observed two clusters among countries with similar news sentiments (Figure 3). The larger cluster contained Bangladesh, China, India, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, and the smaller cluster contained Pakistan, Qatar, the UK, and the US. India (6) was the most connected country, followed by Bangladesh, China, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia (each 5), which belonged to the larger cluster. Only India connected the two clusters by connecting with Qatar and the UK.

Figure 3.

Sentiment similarities among countries. The flag used in each node of the network represents each selected country.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The Rohingyas are one of the most tormented and persecuted communities in the world, who have been denied lands and rights in their motherland. Their plight has widely been documented by news media and studied in academia. In this research, we computationally analyzed more than 8000 news articles on Rohingya issues from ten selected countries to understand how Rohingya news sentiments have evolved over the years in different countries and whether there are any significant differences in news sentiments. Our study revealed that Rohingya-related news sentiments are predominantly negative and fluctuate over the years in different countries, maintaining few identifiable patterns. Additionally, there is significant variation in news sentiments among countries, with some countries exhibiting more similar sentiments than others, thus creating distinguishable groups.

While the overall news sentiment is negative, it is crucial to acknowledge that this negativity does not always imply a negative representation of the Rohingya in the news. Broadly speaking, we identified at least two major contexts for negative sentiments.

First, some news in a few news media portrays the Rohingya as a problematic community. This portrayal is based on real events. Although Rohingyas face persecution by the Myanmar army, their involvement in criminal activities in host countries has drawn wide criticism (Sakib 2023). For example, India and Bangladesh, both host countries and Myanmar’s neighbors, have published news stories about Rohingyas disturbing social peace with unlawful activities, including fighting, drug peddling, and confronting local people, which are factually correct. The Daily Star published a news story with the headline “12 Rohingyas hurt in a clash at Nayapara camp in Teknaf,” describing a fight between two groups of Rohingyas who ended up injuring themselves. Similar stories are present in the dataset but are small in number. This acceptable journalistic practice for upholding the truth should not be discouraged or criticized. Therefore, we caution against equating negative news with a negative portrayal. Journalists have to publish the truth, and publishing valid news about the Rohingyas’ wrongdoing should not be conflated with their negative portrayal.

Previous studies have found similar portrayals, including interest-driven misrepresentations, problematic. Das et al. (2022), Ehmer and Kothari (2021), Wani (2022), Kironska and Peng (2021), and R. Lee (2019) identified that the media is more inclined to describe Rohingyas negatively. Initially, our sentiment scores and trends support these findings. Specifically, the findings of Das et al. (2022) in the context of Bangladesh, Ehmer and Kothari (2021) in Malaysia, and Wani (2022) in India pointed out negative attitudes of these countries’ media toward the Rohingya, which align with our results. However, our findings indicate that media in these countries exhibit lower negative sentiments than other countries, an observation absent in previous single-country-focused studies.

Second, while sometimes negative sentiment may imply a negative portrayal of the Rohingya, through close reading, we found instances where news media have featured their plight using strong language, such as killings, genocide, torturing, and expatriating. For example, media in Muslim countries like the Saudi Gazette and Al Jazeera have published several stories depicting the Rohingyas’ humanitarian situations and crises, including state-organized persecution, cleansing, and displacement. Al Jazeera published news in September 2016 with the headline “Persecution path: Following Myanmar’s fleeing Rohingya,” describing the continuous plight of the Rohingyas. Still, our sentiment score identified it as negative. We found some instances of such inconsistencies in our dataset. Automated sentiment analysis using machine learning is not yet fully operationalized to detect the content’s context accurately and attribute proper sentiments accordingly, which is a major limitation of this type of analysis. To address this, we complemented our automated insights with manual qualitative analysis to minimize misleading inferences. Nonetheless, we caution against overgeneralizing some of our findings without further validation.

Our findings indicate significant variation in news sentiments and their changing patterns in the selected countries, highlighting the media’s differential representations of Rohingya issues. Since previous studies lack longitudinal insights into these representations, it is difficult for us to compare and contrast them directly with our findings. However, our research offers a fresh perspective on understanding and assessing the journalistic portrayal of humanitarian topics over time.

Apart from the substantial variation in news sentiments, we found that some pairs of news media exhibit similar sentiment patterns. The larger cluster includes Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, while the smaller cluster includes Pakistan, Qatar, the UK, and the US, with India connecting both clusters. This finding is complex to explain as both clusters consist of countries with diverse hosting, political, religious, and regional contexts. Hallin and Mancini’s (2004) theory may partially explain this trend. According to the concept, the larger cluster combines elements of the Polarized Pluralist (e.g., China) and Democratic Corporatist (e.g., Malaysia) models of media, where political influence on media behavior is significant but varies in intensity and form.

In contrast, the smaller cluster aligns more with the Liberal Model (e.g., the US), where market forces and sensationalism might drive more consistently negative coverage. It still leaves many concerns unresolved. For example, India bridged the two clusters: how should we define its media system? Both clusters contain mixed media models from different political systems, going beyond the authoritarian vs. liberal or democratic vs. non-democratic binaries (Siebert et al. 1956). It appears that the media agenda, the media and the country’s multifaceted relations (e.g., geographic, economic, diplomatic, cultural, religious) to the crisis, global political and public sentiment, and temporality of the events may have impacts on the media’s behavior (Shujen Wang 1992; Wu 2000), which we found difficult to explain with both Hallin and Mancini’s (2004) and Siebert et al.’s (1956) theories. Further research and novel frameworks are required to explain and substantiate these issues.

Regarding comparative sentiments across countries, we found contradictory insights from previous studies. For example, Rhaman (2023) identified dissimilarities in news sentiments between India and China regarding Rohingya coverage, whereas our findings indicate similar sentiment patterns. Similarly, Irom et al. (2022) found that Bangladesh, Pakistan, Canada, and the US framed the Rohingya issues similarly. While our findings align to some extent with the observation that news sentiments in these countries are inherently negative, they do not provide insights into framing these issues. However, sentiment is an important element of news framing (Burscher et al. 2016), suggesting that further framing analysis could complement our sentiment analysis and provide a more comprehensive understanding of media representation of Rohingya issues.

Bangladesh is the top hosting country, with more than a million Rohingya refugees (Alam 2019). It surprised us that Bangladeshi news media published news with lower negative and higher positive sentiments than other countries, indicating a more positive and perhaps optimistic attitude toward the crisis. The ongoing relief activities, mostly from Middle Eastern Muslim countries like Saudi Arabia and Turkey, along with international cooperation and attention to alleviate the Rohingyas’ plight, the progress of repatriation talks with Myanmar, and resettlements of the Rohingyas in Bangladesh received significant coverage in the Bangladeshi media. We presume these factors are responsible for the higher positive tones in the news. From the very beginning of the crisis, Bangladesh has been vocal about this genocide and amicable towards this displaced community.

Our findings contrast with Ubayasiri (2019), who studied the same Bangladeshi newspaper, The Daily Star, and claimed that the newspaper did not maintain a human-rights-based journalistic approach. This discrepancy may result from our different methodological choices, but our study included a larger corpus with an unobtrusive method of analysis to avoid possible researcher bias (R. M. Lee 2000).

To sum up, we focused on two major areas in our discussion. Firstly, similarities in news sentiments while covering the Rohingya issue are difficult to explain completely, even with established theories like Comparing Media Systems (Hallin and Mancini 2004), as the media systems of the paired countries are often different, mainly in terms of religious orientation and political systems. We may need novel frameworks to explain such anomalies. Secondly, beyond negative representations of the Rohingyas in different countries’ media, we suspect scholarly bias against valid journalistic practices. While it is undeniable that journalists must play responsible roles in this humanitarian refugee crisis, and many may fail to do so, it might be misleading to assume that Rohingyas do not cause problems in host countries. Valid journalistic practices should not be conflated with negative portrayals (Ubayasiri 2019; Wani 2022), as accurately reporting issues related to the Rohingyas is essential for upholding journalistic integrity.

Limitations and Contributions

This study has a few limitations. First and foremost, the current models of sentiment analysis are limited in providing contextual analysis and insights, limiting their explainability. Although we complemented the insights from sentiment analysis accompanied by a manual qualitative reading of the news reports, we suspect this approach may fall short without proper methodological triangulation. Therefore, we recommend that future researchers reconsider integrating a proper qualitative method (e.g., qualitative textual/thematic analysis) to provide a robust, holistic, and in-depth understanding of the topics.

Second, while we encompass a substantial corpus of textual data, certain countries’ news media may offer insufficient coverage of Rohingya issues, resulting in smaller datasets than others. For instance, China Daily of China published only 246 news reports, the lowest in the dataset, while The Daily Star in Bangladesh published the highest number, with 2053 news stories. However, standard NLP libraries like Polyglot can handle smaller corpora effectively and produce reliable results, reducing the chances of potential bias.

Third, we analyzed content from one news outlet per country, limiting our findings’ generalizability. Although we scrutinized each news outlet before purposively selecting them, we believe this is still insufficient since a country hosts different types of media with differing ideologies and publishes the same stories from different angles. Including more outlets from each country could have resolved this issue. However, resource constraints posed a problem for us in this regard.

Finally, sentiment can be viewed from emotional dimensionalities, as proposed in classical studies by Russell (1980) and Ekman (1992). As our research was limited to three dimensions of sentiment, future researchers aspiring to methodological experimentation can consider incorporating varied emotions into sentiment analysis.

Apart from these perceived limitations, our study offers a novel methodological guide for digital humanities research emerging from the communication and media studies discipline. Although news tone analysis employing traditional research methods, such as content analysis, is commonplace in academic scholarship, state-of-the-art computational and machine learning techniques like automated sentiment analysis and topic modeling have only been gaining momentum in recent years. We contribute to this burgeoning literature by combining cutting-edge computational and traditional statistical methods.

Beyond methodological contributions, our findings are theoretically important as they provide fresh perspectives into a journalistic and humanitarian phenomenon, investigating the research problem from a distinct angle compared to previous studies (e.g., Ehmer and Kothari 2021; Irom et al. 2022; Kironska and Peng 2021; Wani 2022). We also stress that journalistic reporting on true events should not be conflated with intentional misrepresentation. Our study underscores the need for responsible journalism that accurately represents the complexities of the Rohingya crisis without succumbing to bias or sensationalism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.A.-Z. and M.H.O.R.; methodology, M.S.A.-Z.; software, M.S.A.-Z.; validation, M.S.A.-Z.; formal analysis, M.S.A.-Z. and M.H.O.R.; investigation, M.S.A.-Z.; resources, M.S.A.-Z. and M.H.O.R.; data curation, M.S.A.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.A.-Z. and M.H.O.R.; writing—review and editing, M.S.A.-Z. and M.H.O.R.; visualization, M.S.A.-Z.; supervision, M.S.A.-Z.; project administration, M.S.A.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is open-access, available in the following repository: https://doi.org/10.17632/hjfsvfhnzb.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbas, Ali Haif. 2024. A Critical Cognitive-Discourse Analysis of the Rohingya Crisis in the Press. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAgha, Iyad. 2021. Topic Modeling and Sentiment Analysis of Twitter Discussions on COVID-19 from Spatial and Temporal Perspectives. Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice 9: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Sorwar. 2019. Top Rohingya-Hosting Countries. Anadolu Agency. Available online: https://aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/infographic-top-rohingya-hosting-countries/1563674 (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Backfried, Gerhard, and Gayane Shalunts. 2016. Sentiment Analysis of Media in German on the Refugee Crisis in Europe. In Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management in Mediterranean Countries: Third International Conference, ISCRAM-med 2016, Madrid, Spain, 26–28 October 2016. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing. Cham: Springer, vol. 265, pp. 234–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoloi, Monali, and Saroj Kumar Biswas. 2023. Sentiment analysis: A survey on design framework, applications and future scopes. Artificial Intelligence Review 56: 12505–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burscher, Bjorn, Rens Vliegenthart, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2016. Frames Beyond Words. Social Science Computer Review 34: 530–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Chung-Hong, Hartmut Wessler, Eike Mark Rinke, Kasper Welbers, Wouter van Atteveldt, and Scott Althaus. 2020. How Combining Terrorism, Muslim, and Refugee Topics Drives Emotional Tone in Online News: A Six-Country Cross-Cultural Sentiment Analysis. International Journal of Communication 14: 3569–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Jingfeng, Zhaoxia Wang, Seng-Beng Ho, and Erik Cambria. 2023. Survey on sentiment analysis: Evolution of research methods and topics. Artificial Intelligence Review 56: 8469–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, Shudipta, Anika Anjum, Sharun Akter Khushbu, and Sheak Rashed Haider Noori. 2022. Public Sentiment Analysis with Opinion Mining on Rohingya Refugee Crisis in Bangladesh. Paper presented at 2022 13th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Virtual, October 3–5; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmer, Emily, and Ammina Kothari. 2021. Malaysia and the Rohingya: Media, Migration, and Politics. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 19: 378–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, Paul. 1992. An Argument for Basic Emotions. Cognition and Emotion 6: 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Daniel C. 2016. The Function of Media System Typologies History of Research on Media Systems. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics Typology of Media Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Jonathan. 2012. Comparing media systems. In The Handbook of Comparative Communication Research. Edited by Frank Esser and Thomas Hanitzsch. London: Routledge, pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, Andreas, and Nick Couldry. 2009. What should comparative media research be comparing?: Towards a transcultural approach to ‘media cultures’. In Internationalizing Media Studies. Edited by Daya Kishan Thussu. London: Routledge, pp. 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Muhammad Nihal, Kiran Kumar Bandeli, Samer Al-khateeb, and Nitin Agarwal. 2018. Analyzing shift in narratives regarding migrants in Europe via blogosphere. Paper presented at First Workshop on Narrative Extraction from Text, Grenoble, France, March 26. Edited by Alípio M. Jorge, Ricardo Campos, Adam Jatowt, and Sérgio Nunes. CEUR Workshop Proceedings. pp. 1–8. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2077/paper4.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Irom, Bimbisar, Porismita Borah, Anastasia Vishnevskaya, and Stephanie Gibbons. 2022. News Framing of the Rohingya Crisis: Content Analysis of Newspaper Coverage from Four Countries. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 20: 109–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaker, Osama, Mohamed Oklah Abughazlih, and Mohd Faizal Kasmani. 2020. Media framing of minorities’ crisis: A study on Aljazeera and BBC news coverage of the Rohingya. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication 36: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kironska, Kristina, and Ni-Ni Peng. 2021. How state-run media shape perceptions: An analysis of the projection of the Rohingya in the Global New Light of Myanmar. South East Asia Research 29: 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopacheva, Elizaveta, and Victoria Yantseva. 2022. Users’ polarisation in dynamic discussion networks: The case of refugee crisis in Sweden. PLoS ONE 17: e0262992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Raymond M. 2000. Unobtrusive Methods in Social Research. London: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Ronan. 2019. Extreme Speech in Myanmar: The Role of State Media in the Rohingya Forced Migration Crisis. International Journal of Communication 13: 3203–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, Hallin. 2010. Comparing Media Systems: A Reponse To Critics. In The Handbook of Comparative Communication Research. Edited by Frank Esser and Thomas Hanitzsch. London: Routledge, vol. 17, pp. 207–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2022. Organisation of the Islamic Cooperation. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Turkey. Available online: https://mfa.gov.tr/OIC.en.mfa (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Nandwani, Pansy, and Rupali Verma. 2021. A review on sentiment analysis and emotion detection from text. Social Network Analysis and Mining 11: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerone, John. 2018. Four Theories of the Press. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostini, Jennifer, and Anthony Y. H. Ostini. 2002. Beyond the Four Theories of the Press: A New Model of National Media Systems. Mass Communication and Society 5: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Nazan, and Serkan Ayvaz. 2018. Sentiment analysis on Twitter: A text mining approach to the Syrian refugee crisis. Telematics and Informatics 35: 136–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, David, and Josephine Griffith. 2016. An Analysis of Online Twitter Sentiment Surrounding the European Refugee Crisis. Paper presented at the 8th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management, Porto, Portugal, November 9–11, vol. 1, pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaman, Harisur. 2023. A Closer Look. In The Displaced Rohingyas, 1st ed. Edited by Sk Tawfique M. Haque, Bulbul Siddiqi and Mahmudur Rahman Bhuiyan. Delhi: Routledge, pp. 178–97. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, James A. 1980. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39: 1161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, A. B. M. Najmus. 2023. Rohingya Refugee Crisis: Emerging Threats to Bangladesh as a Host Country? Journal of Asian and African Studies, 00219096231192324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCImago Media. 2024. SCImago Media Rankings. SCImago Media. Available online: https://scimagomedia.com/rankings.php (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Siebert, Fred, Theodore Peterson, and Wilbur Schramm. 1956. Four Theories of the Press. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Kian Long, Chin Poo Lee, and Kian Ming Lim. 2023. A Survey of Sentiment Analysis: Approaches, Datasets, and Future Research. Applied Sciences 13: 4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubayasiri, Kasun. 2019. Framing statelessness and ‘Belonging’: Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh’s The Daily Star newspaper. Pacific Journalism Review 25: 260–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vaca-Baqueiro, Maira T. 2018. Four Theories of the Press: 60 Years and Counting. In Four Theories of the Press. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, Hong Tien, and Nyan Lynn. 2020. When the News Takes Sides: Automated Framing Analysis of News Coverage of the Rohingya Crisis by the Elite Press from Three Countries. Journalism Studies 21: 1284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shujen. 1992. Factors influencing cross-national news treatment of a critical national event. International Communication Gazette 49: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M. Ibrahim. 2022. From frames of victimhood to that of othering. In The Routledge Handbook of Refugees in India. Delhi: Routledge India, pp. 814–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Denis. 2000. Systemic Determinants of International News Coverage: A Comparison of 38 Countries. Journal of Communication 50: 110–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Zhongheng. 2016. Missing data imputation: Focusing on single imputation. Annals of Translational Medicine 4: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).