Abstract

Concerns around the definition of misinformation hamper ways of addressing purported problems associated with it, along with the fact that public understanding of the concept is often ignored. To this end, the present pilot survey study examines three broad issues, as follows: (1) contexts where the concept most applies to (i.e., face-to-face interactions, social media, news media, or all three contexts), (2) criteria people use to identify misinformation, and (3) motivations for sharing it. A total of 1897 participants (approximately 300 per country) from six different countries (Chile, Germany, Greece, Mexico, the UK, the USA) were asked questions on all three, along with an option to provide free text responses for two of them. The quantitative and qualitative findings reveal a nuanced understanding of the concept, with the common defining characteristics being claims presented as fact when they are opinion (71%), claims challenged by experts (66%), and claims that are unqualified by evidence (64%). Moreover, of the 28% (n = 538) of participants providing free text responses further qualifying criteria for misinformation, 31% of them mentioned critical details from communication (e.g., concealing relevant details or lacking evidence to support claims), and 41% mentioned additions in communication that reveal distortions (e.g., sensationalist language, exaggerating claims). Rather than being exclusive to social media, misinformation was seen by the full sample (n = 1897) as present in all communication contexts (59%) and is shared for amusement (50%) or inadvertently (56%).

1. Introduction

Many institutions have sounded the alarm on the threats posed by misinformation and its darker cousin, disinformation (e.g., the World Economic Forum (WEF), Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), World Health Organisation (WHO), United Nations (UN), and European Commission (EU)). In these institutions, misinformation features at the top of global risk registers (WEF 2024), is the basis for a new scientific discipline called “Infodemiology” (WHO 2020, 2024), is targeted through new codes of practice (European Commission 2022), and now has international expert steering groups to address it (OECD 2021, 2023).

1.1. So, What Is Misinformation?

Misinformation is an example of a term whose definition is in contention; the research community has yet to settle on what it is (e.g., Adams et al. 2023; Grieve and Woodfield 2023; Karlova and Lee 2011; Nan et al. 2023; Roozenbeek and Van der Linden 2024; Scheufele and Krause 2019; Southwell et al. 2022; Tandoc et al. 2018; Vraga and Bode 2020; Van der Linden 2023; Wang et al. 2022; Yee 2023; Zeng and Brennen 2023; Zhou and Zhang 2007). Problems with definitions are a mainstay of academic research, in part because it takes time for a research community to agree on essential criteria.

Misinformation, while not new, is developing into its own dedicated field of study with multiple communities designing research approaches to investigate it. As an emerging research endeavour, it continues to adapt to new findings, which add new facets to the phenomenon. Because misinformation carries considerable weight beyond academia, especially when claimed to be an existential threat, the requirements for a coherent agreed definition are necessary for basic and applied research. In turn, the classification of real phenomena into those that are and are not candidates of misinformation cannot succeed without an agreed definition (Adams et al. 2023; Freiling et al. 2023; Swire-Thompson and Lazer 2020). What is more, the topic has profound implications for journalism and the necessary standards needed to ensure that accurate news coverage is conveyed in real time, or corrected appropriately when facts about world events change (e.g., Pickard 2019). In addition, there is considerable interest in examining how media literacy can help prepare people for ways to scrutinise news that comes to them in different forms, and this could include wild distortions of facts (e.g., Hameleers 2022).

For all of the aforementioned reasons, there are continuing efforts to determine the key properties of misinformation (e.g., Tandoc et al. 2018; Vraga and Bode 2020; Wang et al. 2022; Roozenbeek and Van der Linden 2024). To support this, the aim here is to begin by undertaking a comprehensive examination of definitions of misinformation in academic research and in public policy organisations across a range of years (1983–2024); the reason for the latter is because the term has policy functions and so, has consequences beyond academia. Therefore, in the next section, the definitions proposed are examined in detail from the published academic literature and by public policy in white papers (Table 1). While not every public policy organisation’s definition of misinformation is included, key examples are referred to.

Table 1.

Illustrations of definitions of misinformation presented in academic publications and public institutions.

Furthermore, the value of this exercise is to complement the main focus of this present pilot study. This pilot survey investigates the criteria that the public views as the most closely aligned to their understanding of term misinformation, which, to date, is still underexplored (Lu et al. 2020; Osman et al. 2022). Along with this, because misinformation is assumed to be rampant on social media (e.g., Muhammed and Mathew 2022), it is also worth investigating if the public aligns with this assumption and, in turn, their reasons for sharing it on social media platforms. Finally, outside of extending the limited evidence base, the applied value of this study is that it can show where there are departures between the public’s construal of misinformation and official definitions. If there is misalignment between the two, then knowing this can illuminate future research efforts to see why the misalignment exists, in particular because of how people appraise it when they encounter it in media offline, as well as online.

1.2. Definitions of Misinformation: Inconsistencies vs. Multidimensional Properties

On the surface, the official characterisation of misinformation seems intuitive. It broadly concerns content that is inaccurate or false (see Table 1 for examples). Unfortunately, this unravels fairly quickly because by necessity, it requires a framework for what truth is (e.g., Dretske 1983; Stahl 2006) to know what the departures from it are (for discussion see Adams et al. 2023). For some, a simple dichotomy can be applied (i.e., truth vs. falsehood) (e.g., Levi 2018; Qazvinian et al. 2011; Van der Meer and Jin 2019). Others prefer a continuum between completely true and completely false (Hameleers et al. 2021) or the use of frameworks with several dimensions on which truth, falsity, and intentions are mapped (Tandoc et al. 2018; Vraga and Bode 2020). Complications also arise because misinformation is also defined relative to new terms that refer to intentions to distort the truth (i.e., disinformation) or malicious use of the truth (i.e., malinformation). Therefore, to make the analysis here manageable, the focus is exclusively on definitions of misinformation, and, as is apparent by looking at Table 1, there is considerable variation.

Beyond definitions that solely focus on the properties of the content itself (i.e., that it is false or inaccurate, includes some form of distortions of details, or contains information presented out of context), some definitions also make reference to the intentions of the sender of misinformation (See Table 1). For some definitions, the outcome of misleading the receiver of the content is accidental because the sender is unaware they are conveying inaccurate or false information (See Table 1). To complement this, some definitions also make reference to the state of mind of the receiver of misinformation (see Table 1). This acknowledges that we may, as receivers, misinterpret or misperceive some details and commit them to memory in their distorted state. In turn, we communicate our misapprehensions to others; thus, we are both the recipient and sender of misinformation.

Other definitions refer to the sender as knowingly communicating content to mislead the receiver (See Table 1). The problem here is that it conflates misinformation with definitions of disinformation. Currently, there are serious ramifications for individuals or organisations found to have intentionally disseminated inaccurate or false content deemed harmful (e.g., democratically, economically, socially). In fact, this is the case in several countries where laws are being devised or are already in effect (e.g., China, France, Germany, Ireland, Kenya, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, the USA) (e.g., Aaronson 2024; Colomina et al. 2021; Saurwein and Spencer-Smith 2020; Schiffrin and Cunliffe-Jones 2022; Tan 2023). If the defining characteristics of misinformation and disinformation are indistinguishable, then either one of the terms is not needed, or else some other property should separate them.

Recent definitions make reference to the medium in which false or inaccurate details are disseminated, along with the act of sharing (Table 1). These latest additions reflect growing concerns about access to misinformation, particularly on social media (e.g., Freelon and Wells 2020; Kumar and Geethakumari 2014; Lewandowsky et al. 2012; Malhotra and Pearce 2022; Pennycook and Rand 2021, 2022; Rossini et al. 2021; Wittenberg and Berinsky 2020). In particular, because more people consume news media online, whether warranted or not (Altay et al. 2023; Marin 2021), the concern is that it has been polluted by misinformation that can be shared more widely and quickly (e.g., Del Vicario et al. 2016; Hunt et al. 2022). As a consequence, some definitions specifically refer to social media because this access point to misleading people is potent (see Table 1).

Transmission Heuristic

Over the span of 50 years, the definition of misinformation has shifted considerably to include properties that are more psychologically oriented because they refer to the state of mind of the sender and receiver, as well as their behaviours (e.g., sharing). As seen in Table 1, there are those that (1) focus exclusively on characterising properties of the content itself, (2) refer to the state of mind of the receiver, (3) refer to the intentions of the sender, (4) refer to sharing behaviours, and (5) focus on the medium through which content is communicated. To succinctly capture these changes, underlying the expansion of the criteria of misinformation is a heuristic. It makes a simple value judgment with regards to the psychological features of the transmission of content—transmission heuristic. The transmission heuristic equates “good” (accurate/true) information to “good mental states” to “good” behaviour, and “bad” (inaccurate/false) information to “bad mental states” to “bad” behaviour. In this way, the transmission heuristic neatly synthesises the various definitions into those that only focus on the properties of content of transmission, differentiating it from those that ascribe psychological properties to mental states and from those that refer to the behavioural consequences of what is transmitted. In so doing, what this analysis shows is that there is a presumed causal relationship between the content, mental states, and behaviour. However, as has been shown in recent work (Adams et al. 2023), there are currently no reliable evidential grounds for demonstrating that misinformation is directly and exclusively related to aberrant behaviour via substantive changes in beliefs. This is no different for accurate information and the causal consequences on changing mental states and behaviour in predictable ways. Moreover, this kind of simple causal model reflects a limited interpretation of the nature of our cognition and corresponding value judgments that can be reliably applied. What is more, it ignores the vast psychological literature on the complex relationship between beliefs and behaviour.

2. Purposes of This Pilot Study

As mentioned earlier, many have acknowledged that there is considerable variation in the definition of misinformation. However, while this is appreciated, it remains independent of empirical research examining people’s ability to accurately classify examples of misinformation from truthful content (e.g., Pennycook et al. 2019), their sharing of misinformation (e.g., Chen et al. 2015; Metzger et al. 2021; Pennycook et al. 2019; Perach et al. 2023), and metrics for identifying those most susceptible to it (e.g., Maertens et al. 2023). To better understand the application of the term misinformation in academic research and beyond, this present pilot study aims to explore it from the public’s own perspective.

There is limited work that has examined the public’s understanding of the term misinformation (Osman et al. 2022). A representative sample of participants (N = 4407) from four different countries (Russia, Turkey, the UK, the USA) were asked what they took misinformation to mean. The majority (~60%) agreed or strongly agreed with the definition “Information that is intentionally designed to mislead”. Compare this to the smaller proportion that agreed or strongly agreed (~30%) with the definition of misinformation as “Information that is unintentionally designed to mislead”. This reflects a similar ambiguity in the way misinformation is understood in academic literature. In addition, when probed further regarding the specific properties of the content, Osman et al. (2022) found that the most common property was claims that exaggerated conclusions from facts (43%); next was content that did not provide a complete picture (42%) or else content that was presented as fact but was opinion or rumour (38%). Of further note, this pattern of responses did not vary by education level, and there are two reasons for why this is important. First, a popular claim is that less-educated individuals are more susceptible to misinformation and conspiracy theories than their university-educated counterparts (e.g., Nan et al. 2022; Scherer et al. 2021; Van Prooijen 2017). However, there are studies showing that there is no reliable relationship between the level of education and susceptibility to misinformation (e.g., Pennycook and Rand 2019; Wang and Yu 2022), or even the opposite, regarding the perceived ability to detect misinformation (e.g., Khan and Idris 2019). A second assumption is that the level of education is correlated with media literacy (e.g., Kleemans and Eggink 2016), so that the more educated one is, the better able one is to analyse media content. Though here also, there does not appear to be a stable relationship between the two (e.g., Kahne et al. 2012), but other factors matter more (e.g., interest in current affairs, civil engagement) (e.g., Ashley et al. 2017; Martens and Hobbs 2015). Thus, this present study aims to explore if indeed interpretations of the term misinformation are differentiated by educational level. The main focus of this present pilot study is to considers the following three critical factors: (1) the contexts where misinformation most commonly applies to (social media, face-to-face interactions, news media); (2) the key criteria used to determine if a transmission constitutes misinformation; and (3) the reasons for sharing what might be suspected to be misinformation.

3. Methods

Participants and Design

A total of 1897 participants took part in the pilot survey. The inclusion criteria for taking part were that participants were born in and were current residents of each respective country that was included in this study—Chile, Germany, Greece, Mexico, the UK, and the USA (see Table 2). The selection of the six countries was opportunistic and based on access to large samples. In addition, participants had to be a minimum of 18 years of age to take part in this study (age restrictions were 18 to 75 for all samples). Ethics approval for this pilot study was granted by the College Ethics board, Queen Mary University of London, UK (QMREC1948). Participants were required to give informed consent at the beginning of the web survey before participating. The full raw data file of demographics and responses of all the participants is available at https://osf.io/uxm7c.

Table 2.

The total sample includes N = 1897 adult participants from six countries.

Participants were asked to indicate their gender (Male = 53.4%; Female = 45.1%, Other = 1.2%, Prefer not to say = 0.3%). They also indicated their age (18–24 = 38.3%; 25–34 = 37.4%; 35–44 = 14.3%; 45–54 = 6%; 55+ = 4%). They provided details of their education level, which was adapted for each country (Level 1 (up to 16 years) = 5.5%; Level 2 (up to 18 years) = 35.1%; Level 3 (Undergraduate degree) = 42.5%; Level 4 (Postgraduate degree) = 14.6%; Level 5 (Doctoral degree) = 1.6%). Additionally, they provided details of their political affiliation, also adapted for each country and presented on an 8-point scale, with 1 (extremely liberal) and 7 (extremely conservative) and 0 (no political affiliation) (0 = 8.6%; 1 = 14.5%; 2 = 24.4%; 3 = 25.9%; 4 = 15%; 5 = 7.8%; 6 = 2.6%; 7 = 1.2%). Note that because the pilot survey did not use a representative sampling method, the findings presented in the results section were not based on examining the pattern of responses with respect to demographic factors or by country comparisons.

This simple pilot survey was run via the online survey platform Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/), and participants were recruited via Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/), an online crowd-sourcing platform. The process of recruitment via Prolific was volunteer sampling. Overall, the pilot survey contained three main dependent variables (Context in which misinformation most applies, Characteristic of misinformation, Sharing reasons) and five demographic details—country, age, education level, gender, and political affiliation. All participants were presented with the same questions in the same order, because the latter two questions were informed by responses to the first question. The survey took approximately 5 min to complete, and participants were paid 0.88 USD for their time (equivalent to a rate of 10.56 USD per hour at the time the study was run).

4. Procedure

Once participants had given their consent and provided their demographic details, they were then presented with the first main dependent variable, which referred to the context in which the concept of misinformation most commonly applies (See Table 3). They were then presented with the second dependent variable, which referred to a range of criteria used to identify a transmission as misinformation (See Table 3), and then the final dependent variable, which referred to reasons given for sharing misinformation (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Questions presented to participants in the pilot survey.

Once they had completed these questions and the two open-ended free text questions, the survey was complete; the data file with the coded responses for the open-ended question, Question 1, can be found here: https://osf.io/64qfp, and the coded responses for Question 2 can be found here: https://osf.io/hpfrt.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Finding 1: Common Contexts in Which the Term Misinformation Most Applies

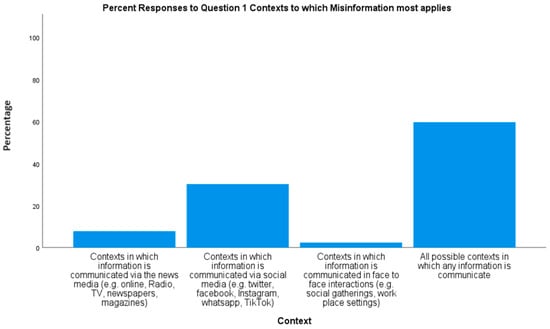

The findings show that the context in which people perceive that the concept of misinformation most applies is in all possible communication contexts (59.6%), which in this case, includes the following: news media (e.g., online, radio, TV, newspapers, magazines), social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, TikTok), and face-to-face interactions (e.g., social gatherings, workplace settings). Few specifically identified social media (30.2%) as the communication context where the concept of misinformation most exclusively applies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of responses to each of the four possible communication contexts where the concept of misinformation most applies.

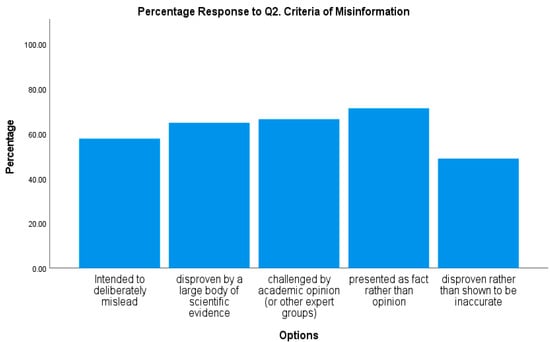

5.2. Finding 2: Common Defining Characteristics of the Term Misinformation

The findings show (see Figure 2) that the most frequently agreed-upon criterion for defining misinformation was presenting information as fact rather than opinion (71.2%), or that has been found to be challenged by experts (66.4%), or else later disproven by evidence (64.8%). The latter two suggest that some value is placed on validating communication by an authority, or with reference to empirical work; this is further explored in the free text analysis.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Yes responses to each of the five stated definitions of misinformation.

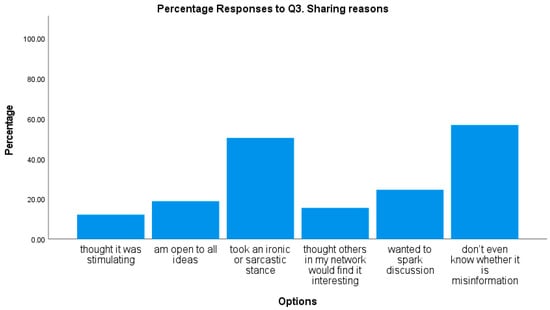

5.3. Finding 3: Reasons for Sharing Misinformation

The last question pertained to reasons for sharing misinformation. People mostly selected approximately two (M = 1.8; SD = 1) out of the six possible reasons for sharing misinformation. The two most common reasons were that the information was shared unwittingly (56.7%) or deliberately for amusement purposes (50.3%) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of responses to the six possible reasons for sharing misinformation.

5.4. Finding 4: Open Question 1 on Criteria for Determining Misinformation

Of the 1897 participants that took part, a total of 618 (33%) volunteered details in the free text box to further qualify their responses to Question 2. While 6 responded that they were unsure of what the open-ended question was asking them to do, 74 participants explicitly stated that they were happy with the options that they were provided in Question 2. This is, in of itself, useful information, as it suggests that they considered the options a reasonable representation of their own considerations. The remaining 538 participants further qualified factors that they considered as relevant to understanding the term misinformation.

Demographics. Of the 538 that provided details in the free text box, approximately 76% were between the ages of 18–34, and 24% were 35–54%, with 53% males and 45% females, and the political affiliation was 61% left-leaning and 13% right-leaning, and 35% were non-university graduates and 64% were university graduates. The patterns generally reflected the demographic distribution of the overall sample. Regarding the demographic details of the 74 that endorsed the options already presented, 32% were non-university graduates and 68% were university graduates. Note also that this, too, reflects the general sample distribution of university graduates (~39%) to non-university graduates (~59%).

Coding: After examining all of the free text in detail, the coding frame used to examine the free text first classified the responses into “qualifying the criteria of misinformation”, “provision of an illustration”, “identifying a target/victim of misinformation”, “identifying a source of misinformation”, “identifying motivations for misinformation”, and “identifying a context in which misinformation is found” (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Superordinate coding of free text of the first open question: misinformation criteria.

As presented in Table 4, there was high agreement between the two coders for four of the six criteria on which the free text was classified. The two criteria where there was most disagreement were the examples of misinformation and the context in which misinformation occurred. The main reason for the disagreement was that one of the coders conflated examples with context. After both coders reviewed the free text again, the detailed analysis of the classified free text was based on the maximal agreement between both coders. The only exception was for the example and context classifications. The solution was to collapse across both categories and examine patterns in general regarding where misinformation was reported.

When it came to the category “qualifying the criteria of misinformation”, at a broad level the responses were further classified into three groups (see Table 5). Some (31%) qualified misinformation according to what was absent, such as concealing relevant details or lacking evidence to support claims; these were details that would be necessary to ensure that it was valid or accurate communication. Others (41%) qualified misinformation according to details that were present in communication, such as distortions, sensationalist language, or exaggerating claims.

Table 5.

Detailed coding of free text for the first open question: misinformation criteria.

Another aspect that featured in the way that participants qualified their understanding of misinformation was to refer to the motivations they ascribed to the communication (34%). Of those volunteering motivation reasons, participants explicitly mentioned that misleading the receiver was unintended (6%) or that it could be both intentional as well as unintentional (10%). However, more referred to reasons that indicated that the generator/communicator of misinformation had intentions to mislead, which was referred simply by reference to terms associated with intent (15%). Alternatively, some suggested that there were nefarious motives (17%), such as sowing discord, to be deceitful (5%) or because of financial incentives to communicate distorted or wrong claims (13%). Taken together, this suggests that motivations behind constructing and communicating misinformation is viewed as wilful (50%) rather than unintentional (6%), with some accepting that both are possible.

Other factors (source, examples, context, victim): Some (20%) had explicitly identified sources of misinformation. Of those detailing the source, 19% referred to experts/authorities (including government, media organisation, science, scientists, experts), 18% referred to public figures (influencers, politicians, high-status individuals), 12% suggested the source could be unreliable (self-declared experts, unqualified experts, dubious experts, uneducated individuals), and 25% said it could be anyone (victims as purveyors, anyone). In addition, a wide range of illustrations of misinformation were provided (14%), which include click-bait, Facebook posts, fake news, hearsay, memes, rumours, gossip, myths, conspiracy theories, COVID-19, satire, parody, comedy, video/audio/photographs, news headlines, and body language.

Many of the responses (32%) in the free text referred to contexts where misinformation was expected to be present (see Table 4). Given the level of disagreement between the two coders in the classification of examples, the examples and context classifications were collapsed to examine general areas where misinformation was referred to have occurred (n = 223); where examples were given, they often indicated a context (e.g., Facebook posts—indicated the context was social media). To this end, of the 32% that identified a specific context, there were four common contexts referred to—Social media (16%), News media (19%), Political domains/Politics (14%), or situations where Statistics/Data/Evidence/Scientific claims were communicated (18%). Finally, some responses (15%) made reference to the victim, or the target of misinformation. For those referring to a target, there were five types—Anyone (including self) = 36%, Public (Public, Masses, Population) = 12%, Less informed/trusting individuals (Naïve, trusting, less educated) = 24%, and Targeted groups = 12%, social media users = 14%.

5.5. Finding 5: Open Question 2 on Reasons for Sharing

Of the 1897 participants, a total of 375 (20%) participants volunteered a response in the second open-ended question regarding sharing behaviours. While 6 responded that they were unsure of what the open-ended question was asking them to do, 82 participants responded that they were happy with the options that they were provided in Question 3. The remaining 287 participants provided responses that further qualified factors that they considered regarding motivations behind sharing. Of the 287 free text responses, 21 were uninterpretable, leaving 266 for coding (see Table 6). Once all free text was reviewed to determine themes, the text was classified into three broad categories. Note that while people gave multiple responses, the free text was classified into only one category (not multiple categories), where there were multiple responses; the first response was used as a basis for classification. It was clear that there were three main categories, as follows: those that explicitly indicated that they do not knowingly share misinformation (24%); those that share it unwittingly, for which there are two different factors (simply not knowing (34%), not knowing at the time because of difficulty in verification/was considered valid at the time); and those that share deliberately (for amusement, for illustrative purposes) (35%) (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Volunteered responses to open-ended question on sharing.

The demographic details of respondents were split into three groups—“Avoid sharing”, “Unwittingly shared”, and “Knowingly shared”. It is worth noting that the demographics (see Table 6) seem to reflect the overall general patterns in the overall sample. In particular, it is not the case that education level reflects large differences between those that avoid sharing, share unwittingly, or share knowingly.

6. General Discussion

In summary, this pilot study provides insights that align with those of Osman et al. (2022). Consistent with previous findings (Osman et al. 2022), this present pilot study also found that the majority (59.6%) expect to find misinformation in all communicative contexts and not exclusively on social media (30.2%). This suggests that the public takes a broader line compared with some published definitions that are specifically concerned with the presence of misinformation on social media (see Table 1). One reason for this may be that the public is much more pragmatic and, at the same time, less alarmist in their views of misinformation because they expect that any communication between people will involve inaccuracies and distortions. This speculation requires further empirical investigation in support of it.

When it comes to reasons for sharing, again, the present findings replicate those of Osman et al. (2022). The present sample indicated that if they did share misinformation, the majority did this unwittingly (56.7%). In the qualitative analysis, this is further qualified by explanations people gave that at the time of sharing, it was not officially considered misinformation. Where people knowingly shared misinformation, this was ironically done (50.3%). When looking at the free text responses, people explained that some of the content was satirical, which could, in some cases, qualify under the definition of misinformation. Of those providing free text responses (n = 266), 21% explained that they used the content as a means of correcting misapprehensions amongst their social networks on social media, as well as offline. This finding contrasts recent work suggesting that when people are aware that misinformation is being shared, they may fail to point it out on their social network for fear of offending (Malhotra and Pearce 2022). Overall, this pilot study supports claims that the range of motivations behind communication apply to misinformation as they do information. We are motivated to entertain, inform, and persuade, as well as to manipulate (e.g., Altay et al. 2023; Osman et al. 2022; Pennycook et al. 2019).

The main focus of this pilot study was to examine the public’s construal of misinformation, and the present findings also replicate those of Osman et al. (2022). The most common responses to options regarding key criteria for misinformation were as follows: content that was presented as fact but was opinion (71.2%), claims that had later been challenged by experts (66.4%), or claims that were later disproven by evidence (64.8%). The free text responses (n = 538) further qualified these patterns. When it came to content that was described as consequential (e.g., regarding political content, economic details, world affairs, health recommendations), respondents valued supporting evidence, and so the absence of it, or the obscuring of it, was used as a strong signal that it was misinformation (31%).

Unlike any of the official definitions of misinformation, the free text (n = 538) revealed that the public considers the underlying motivations of the source (34%), which go beyond intentions to mislead. The qualitative data revealed that some communication is harmful because it is designed to be divisive, often because the content is presented in such a way as to prohibit discussion or raise challenges. Some of the responses indicate suspicion that content could be misinformation because of the censorious nature of state communication, which aligns with recent findings (Lu et al. 2020). Some highlighted that there are likely financial incentives to communicate content that is salacious or sensational because it is clickbait, often referred to in association with news media and journalism more broadly.

Overall, the present findings suggest that the public takes a pragmatic approach to what constitutes misinformation, as indicated in the responses to the closed and open questions on the topic. One reason for this interpretation is that people reported that there were times where content was encountered that, at the time, was viewed as accurate but was later invalidated in light of new evidence. This suggests some flexibility in what could count as misinformation at any one time. In fact, this latter point is worth considering further because it also aligns with work discussing the dynamic nature of communication and the temporal status of claims according to what could be known at the time (Adams et al. 2023; Lewandowsky et al. 2012; Osman et al. 2022). The free text responses referred to evidence and scientific claims as ways to illustrate the criteria they considered critical for characterizing misinformation. In fact, when it comes to scientific claims that are communicated to the public, either directly by an academic or translated by journalists or popular science writers, concerns have been raised about exaggerations (Bratton et al. 2019; Bott et al. 2019) or the downplaying of uncertainties (Gustafson and Rice 2020). The latter means that scientific claims, either by scientists or journalists on their behalf, tend towards packaging scientific claims with certitude. Journalistic flair also means that distortions in the original scientific claims are inevitable for the sake of accessibility (Bratton et al. 2019; Bott et al. 2019), but this, according to some official definitions (see Table 1), would qualify as misinformation. What is clear from the present findings is that the public is sensitive to this and knows that license is taken when they are presented with scientific claims in ways that do not provide a complete and accurate picture (Osman et al. 2022).

Given this, and widening the discussion further, it is worth considering the following: What improvements can be achieved in the dissemination of content through media based on insights from the public understanding of misinformation? An appropriate response will depend on what the function of dissemination is and who is executing the dissemination. One possible function of dissemination is for audience engagement (e.g., through the number of views, likes, and shares) (e.g., López and Santamaría 2019), which is best achieved online, not least because it can be quantified easily. If the content is opinion-based, then it is clear that the public are sensitive to when this is disseminated as fact, which they treat as misinformation. To make improvements, should corrective measures apply equally to citizens, journalists,1 activists, the general public, and traditional news journalists? The answer to this involves taking media ethics into account (e.g., Stroud 2019; Ward and Wasserman 2010).

Professional media ethics for traditional journalism (i.e., the pre-digital age) meant upholding principles of truth seeking, objectivity, accountability, and a responsibility to serve the public good (Ward 2014). Digital journalism follows new principles concerned with the active pursuit of public engagement and tailoring news to the presumed needs of a target audience (Guess et al. 2021; Nelson 2021; Ward 2014). Traditional print journalism was understood to have political tilts, but now, with new principles in place, news media is explicitly partisan (e.g., Guess et al. 2021). An example of an agreed fact, regardless of partisan news media, would be reporting the date, time, and location of a political event that occurred. But, depending on the news media outlet and audience (e.g., Kuklinski et al. 1998; Savolainen 2023), the surrounding descriptions, with omissions or commissions of the event, may end up also being treated as fact or as an opinion masquerading as fact. If corrective mechanisms are applied to limit the dissemination of content that the public perceives as misinformation (e.g., opinion presented as fact), then for journalism, this means reintroducing and enforcing pre-digital media ethics, with less partisanship. Corrective measures simply mean publishing corrections with explanations (Appelman and Hettinga 2021; Osman et al. 2023). If the motivation is to engage audiences to serve the public good, then activists and citizen journalists should also follow suit, with the aim of raising the bar regarding the quality and sourcing of support for claims and facts. If the motivations are clear and singular, and dissemination of information is for some public good, then it is fair to expect that those doing so are held to some basic standard of reporting.

7. Limitations

Three main limitations of the pilot survey were that the options presented to people were not fully randomised, so there could have been some biased responding, given the order of presentation of the options of both questions. In addition, the sampling was not designed in a way to ensure representation based on gender, age, and other key demographics. The third limitation is that the question regarding the criteria that people use to judge a piece of information as misinformation presented options that conflated general descriptions of what misinformation could be with the sources that could be used to judge what misinformation could be, with features of the information that would lead people to suspect that it is misinformation. For all these reasons, the presentation of the data in the results section was based on simple descriptives rather than inferential analyses of the data. Acknowledging this, the general patterns still stand as informative, not least because they replicate and extend previous work (Osman et al. 2022), using a wider sample of participants from countries not often included in this field of research.

8. Conclusions

Given how profoundly inconsistent published definitions of misinformation are, this present study was designed to investigate how the public construe the concept. The findings from the present pilot survey show that the majority treats misinformation as a concept that applies to all communication contexts, not just communication online via social media. The majority see opinions presented as facts as an indicator of misinformation, along with claims unsubstantiated by experts or later disproven by evidence. The latter is important because it indicates sensitivity to the temporal nature of claims and their status with respect to evidence, which frequently need updating in precision and accuracy as new findings are uncovered. Sharing is not motivated by efforts to deliberately mislead—to the extent that they are aware; the sharing of misinformation is to stimulate discussion or for entertainment. What the public views as misinformation, and the criteria they apply to their everyday experiences, does not reflect nativity. The public makes pragmatic appraisals based on a number of factors, including motivations and context.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the College Ethics board, Queen Mary University of London. Approval Code: (QMREC1948); approval date: March 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants that took part in the experiment.

Data Availability Statement

All raw data files are publicly available here: https://osf.io/ycfha/.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Roberts (2019) defines citizen journalism as “the involvement of nonprofessionals in the creation, analysis, and dissemination of news and information in the public interest” (p. 1). |

References

- Aaronson, Susan Ariel. 2024. Trade Agreements and Cross-border Disinformation: Patchwork or Polycentric? In Global Digital Data Governance. London: Routledge, pp. 125–47. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Zoë, Magda Osman, Christos Bechlivanidis, and Björn Meder. 2023. (Why) is misinformation a problem? Perspectives on Psychological Science 18: 1436–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, Sacha, Manon Berriche, and Alberto Acerbi. 2023. Misinformation on misinformation: Conceptual and methodological challenges. Social Media + Society 9: 20563051221150412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelman, Alyssa, and Kirstie E. Hettinga. 2021. The ethics of transparency: A review of corrections language in international journalistic codes of ethics. Journal of Media Ethics 36: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, Seth, Adam Maksl, and Stephanie Craft. 2017. News Media Literacy and Political Engagement: What’s the Connection? Journal of Media Literacy Education 9: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aven, Terje, and Shital A. Thekdi. 2022. On how to characterize and confront misinformation in a risk context. Journal of Risk Research 25: 1272–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, Leticia, and Emily K. Vraga. 2015. In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. Journal of Communication 65: 619–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, Leticia, Emily K. Vraga, and Melissa Tully. 2021. Correcting misperceptions about genetically modified food on social media: Examining the impact of experts, social media heuristics, and the gateway belief model. Science Communication 43: 225–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, Lewis, Luke Bratton, Bianca Diaconu, Rachel C. Adams, Aimeé Challenger, Jacky Boivin, Andrew Williams, and Petroc Sumner. 2019. Caveats in science-based news stories communicate caution without lowering interest. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 25: 517–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratton, Luke, Rachel C Adams, Aimée Challenger, Jacky Boivin, Lewis Bott, Christopher D. Chambers, and Petroc Sumner. 2019. The association between exaggeration in health-related science news and academic press releases: A replication study. Wellcome Open Research 4: 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. How to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Available online: https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/cerccorner/article_072216.asp (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Chen, Liang, Xiaohui Wang, and Tai-Quan Peng. 2018. Nature and diffusion of gynecologic cancer–related misinformation on social media: Analysis of tweets. Journal of Medical Internet Research 20: e11515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xinran, Sei-Ching Joanna Sin, Yin-Leng Theng, and Chei Sian Lee. 2015. Why students share misinformation on social media: Motivation, gender, and study-level differences. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 41: 583–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomina, Carme, Héctor Sánchez Margalef, Richard Youngs, and Kate Jones. 2021. The Impact of Disinformation on Democratic Processes and Human Rights in the World. Brussels: European Parliament, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, John. 2017. Understanding and countering climate science denial. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 150: 207–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, Jeroen. 2021. What’s so bad about misinformation? Inquiry, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vicario, Michela, Alessandro Bessi, Fabiana Zollo, Fabio Petroni, Antonio Scala, Guido Caldarelli, H. Eugene Stanley, and Walter Quattrociocchi. 2016. The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 554–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health and Social Care, UK Government. 2015. The False or Misleading Information Offence: Guidance. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a816f2fed915d74e33fe30b/FOMI_Guidance.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Do Nascimento, Israel Júnior Borges, Ana Beatriz Pizarro, Jussara M. Almeida, Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat, Marcos André Gonçalves, Maria Björklund, and David Novillo-Ortiz. 2022. Infodemics and health misinformation: A systematic review of reviews. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 100: 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dretske, Fred I. 1983. Précis of Knowledge and the Flow of Information. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 6: 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2018. A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Disinformation—Report of the Independent High Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=50271 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- European Commission. 2022. Code of Practice on Disinformation. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/2022-strengthened-code-practice-disinformation (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Fox, Chris J. 1983. Information and Misinformation: An Investigation of the Notions of Information, Misinformation, Informing, and Misinforming. Westport: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Freelon, Deen, and Chris Wells. 2020. Disinformation as political communication. Political Communication 37: 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiling, Isabelle, Nicole M. Krause, Dietram A. Scheufele, and Dominique Brossard. 2023. Believing and sharing misinformation, fact-checks, and accurate information on social media: The role of anxiety during COVID-19. New Media & Society 25: 141–62. [Google Scholar]

- Government Communication Service, UK Government. 2021. Available online: https://gcs.civilservice.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RESIST-2-counter-disinformation-toolkit.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Grieve, Jack, and Helena Woodfield. 2023. The Language of Fake News. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guess, Andrew M., Pablo Barberá, Simon Munzert, and JungHwan Yang. 2021. The consequences of online partisan media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118: e2013464118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, Abel, and Ronald E. Rice. 2020. A review of the effects of uncertainty in public science communication. Public Understanding of Science 29: 614–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, Michael. 2022. Separating truth from lies: Comparing the effects of news media literacy interventions and fact-checkers in response to political misinformation in the US and Netherlands. Information, Communication & Society 25: 110–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hameleers, Michael, Toni Van der Meer, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2021. Civilised truths, hateful lies? Incivility and hate speech in false information—Evidence from fact-checked statements in the US. Information, Communication and Society 25: 1596–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Kyle, Puneet Agarwal, and Jun Zhuang. 2022. Monitoring misinformation on Twitter during crisis events: A machine learning approach. Risk Analysis 42: 1728–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahne, Joseph, Nam-Jin Lee, and Jessica Timpany Feezell. 2012. Digital media literacy education and online civic and political participation. International Journal of Communication 6: 24. [Google Scholar]

- Karlova, Natascha A., and Jin Ha Lee. 2011. Notes from the underground city of disinformation: A conceptual investigation. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 48: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. Laeeq, and Ika Karlina Idris. 2019. Recognise misinformation and verify before sharing: A reasoned action and information literacy perspective. Behaviour & Information Technology 38: 1194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kleemans, Mariska, and Gonnie Eggink. 2016. Understanding news: The impact of media literacy education on teenagers’ news literacy. Journalism Education 5: 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kuklinski, James H., Paul J. Quirk, David W. Schwieder, and Robert F. Rich. 1998. “Just the facts, ma’am”: Political facts and public opinion. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 560: 143–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklinski, James H., Paul J. Quirk, Jennifer Jerit, David Schwieder, and Robert F. Rich. 2000. Misinformation and the currency of democratic citizenship. Journal of Politics 62: 790–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K. P. Krishna, and G. Geethakumari. 2014. Detecting misinformation in online social networks using cognitive psychology. Human-Centric Computing and Information Sciences 4: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, David M. J., Matthew A. Baum, Yochai Benkler, Adam J. Berinsky, Kelly M. Greenhill, Filippo Menczer, Miriam J. Metzger, Brendan Nyhan, Gordon Pennycook, David Rothschild, and et al. 2018. The Science of Fake News. Science 359: 1094–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, Lili. 2018. Real “fake news” and fake “fake news”. First Amendment Law Review 16: 232. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich K. H. Ecker, Colleen M. Seifert, Norbert Schwarz, and John Cook. 2012. Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 13: 106–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Werner G. K. Stritzke, Alexandra M. Freund, Klaus Oberauer, and Joachim I. Krueger. 2013. Misinformation, disinformation, and violent conflict: From Iraq and the “War on Terror” to future threats to peace. American Psychologist 68: 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losee, Robert M. 1997. A discipline independent definition of information. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 48: 254–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Mª Cruz López De Ayala, and Pedro Paniagua Santamaría. 2019. Motivations of Youth Audiences to Content Creation and Dissemination on Social Network Sites. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodistico 25: 915–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Zhicong, Yue Jiang, Cheng Lu, Mor Naaman, and Daniel Wigdor. 2020. The government’s dividend: Complex perceptions of social media misinformation in China. Paper presented at 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, April 25–30; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Maertens, Rakoen, Friedrich M. Götz, Hudson F. Golino, Jon Roozenbeek, Claudia R. Schneider, Yara Kyrychenko, John R. Kerr, Stefan Stieger, William P. McClanahan, Karly Drabot, and et al. 2023. The Misinformation Susceptibility Test (MIST): A psychometrically validated measure of news veracity discernment. Behavior Research Methods 56: 1863–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, Pranav, and Katy Pearce. 2022. Facing falsehoods: Strategies for polite misinformation correction. International Journal of Communication 16: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, Lavinia. 2021. Sharing (mis) information on social networking sites. An exploration of the norms for distributing content authored by others. Ethics and Information Technology 23: 363–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, Hans, and Renee Hobbs. 2015. How media literacy supports civic engagement in a digital age. Atlantic Journal of Communication 23: 120–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, Miriam J., Andrew J. Flanagin, Paul Mena, Shan Jiang, and Christo Wilson. 2021. From dark to light: The many shades of sharing misinformation online. Media and Communication 9: 134–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, T. Sadiq, and Saji K. Mathew. 2022. The disaster of misinformation: A review of research in social media. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 13: 271–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, Xiaoli, Kathryn Thier, and Yuan Wang. 2023. Health misinformation: What it is, why people believe it, how to counter it. Annals of the International Communication Association 47: 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Xiaoli, Yuan Wang, and Kathryn Thier. 2022. Why do people believe health misinformation and who is at risk? A systematic review of individual differences in susceptibility to health misinformation. Social Science & Medicine 314: 115398. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Jacob L. 2021. The next media regime: The pursuit of ‘audience engagement’ in journalism. Journalism 22: 2350–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2021. Report on Public Communication: The Global Context and the Way Forward. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2022. Misinformation and Disinformation: An International Effort Using Behavioural Science to Tackle the Spread of Misinformation. OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 21. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2023. Tackling Disinformation: Strengthening Democracy through Information Integrity. Available online: https://www.oecd-events.org/disinfo2023 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Osman, Magda, Björn Meder, Christos Bechlivanidis, and Colin Strong. 2023. To Share or Not to Share, Are There Differences Offline than Online? No. 8. Centre for Science and Policy, University of Cambridge Working Paper Series. Available online: https://www.csap.cam.ac.uk/media/uploads/files/1/offline-vs-online-sharing.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Osman, Magda, Zoe Adams, Bjoern Meder, Christos Bechlivanidis, Omar Verduga, and Colin Strong. 2022. People’s understanding of the concept of misinformation. Journal of Risk Research 25: 1239–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2019. Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition 188: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2021. The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 25: 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2022. Nudging social media toward accuracy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 700: 152–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, Ziv Epstein, Mohsen Mosleh, Antonio A. Arechar, Dean Eckles, and David G. Rand. 2019. Understanding and Reducing the Spread of Misinformation Online. Unpublished Manuscript. pp. 1–84. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/3n9u8 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Perach, Rotem, Laura Joyner, Deborah Husbands, and Tom Buchanan. 2023. Why Do People Share Political Information and Misinformation Online? Developing a Bottom-Up Descriptive Framework. Social Media+ Society 9: 20563051231192032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, Victor. 2019. Democracy without Journalism? Confronting the Misinformation Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qazvinian, Vahed, Emily Rosengren, Dragomir Radev, and Qiaozhu Mei Radev. 2011. Rumor has it: Identifying misinformation in microblogs. Paper presented at 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Edinburgh, UK, July 27–29; pp. 1589–99. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Jessica. 2019. Citizen journalism. The International Encyclopedia of Media Literacy 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Roozenbeek, Jon, and Sander Van der Linden. 2024. The Psychology of Misinformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rossini, Patrícia, Jennifer Stromer-Galley, Erica Anita Baptista, and Vanessa Veiga de Oliveira. 2021. Dysfunctional information sharing on WhatsApp and Facebook: The role of political talk, cross-cutting exposure and social corrections. New Media & Society 23: 2430–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurwein, Florian, and Charlotte Spencer-Smith. 2020. Combating disinformation on social media: Multilevel governance and distributed accountability in Europe. Digital Journalism 8: 820–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, Reijo. 2023. Exploring the informational elements of opinion answers: The case of the Russo-Ukrainian war. Information Research an International Electronic Journal 28: 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, Laura D., Jon McPhetres, Gordon Pennycook, Allison Kempe, Larry A. Allen, Channing E. Knoepke, Christopher E. Tate, and Daniel D. Matlock. 2021. Who is susceptible to online health misinformation? A test of four psychosocial hypotheses. Health Psychology 40: 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheufele, Dietram A., and Nicole M. Krause. 2019. Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 7662–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffrin, Anya, and Peter Cunliffe-Jones. 2022. Online misinformation: Policy lessons from the Global South. Disinformation in the Global South, 159–78. [Google Scholar]

- Southwell, Brian G., Jeff Niederdeppe, Joseph N. Cappella, Anna Gaysynsky, Dannielle E. Kelley, April Oh, Emily B. Peterson, and Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou. 2019. Misinformation as a misunderstood challenge to public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 57: 282–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southwell, Brian G., J. Scott Babwah Brennen, Ryan Paquin, Vanessa Boudewyns, and Jing Zeng. 2022. Defining and measuring scientific misinformation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 700: 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten. 2006. On the difference or equality of information, misinformation, and disinformation: A critical research perspective. Informing Science 9: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, Scott R. 2019. Pragmatist media ethics and the challenges of fake news. Journal of Media Ethics 34: 178–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swire-Thompson, Briony, and David Lazer. 2020. Public health and online misinformation: Challenges and recommendations. Annu Rev Public Health 41: 433–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Rachel. 2023. Legislative strategies to tackle misinformation and disinformation: Lessons from global jurisdictions. Australasian Parliamentary Review 38: 231–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tandoc, Edson C., Jr., Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2018. Defining “fake news” A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism 6: 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, Sander. 2022. Misinformation: Susceptibility, spread, and interventions to immunize the public. Nature Medicine 28: 460–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Linden, Sander. 2023. Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity. New York: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer, Toni, and Yan Jin. 2019. Seeking formula for misinformation treatment in public health crises: The effects of corrective information type and source. Health Communication 35: 560–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem. 2017. Why education predicts decreased belief in conspiracy theories. Applied Cognitive Psychology 31: 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vraga, Emily K., and Leticia Bode. 2020. Defining misinformation and understanding its bounded nature: Using expertise and evidence for describing misinformation. Political Communication 37: 136–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Tianjiao, and Wenting Yu. 2022. Alternative sources use and misinformation exposure and susceptibility: The curvilinear moderation effects of socioeconomic status. Telematics and Informatics 70: 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuan, Kathryn Thier, and Xiaoli Nan. 2022. Defining health misinformation. In Combating Online Health Misinformation: A Professional’s Guide to Helping the Public. Edited by Alla Keselman, Catherine Arnott Smith and Amanda J. Wilson. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Stephen J. 2014. Radical Media Ethics: Ethics for a global digital world. Digital Journalism 2: 455–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Stephen J., and Herman Wasserman. 2010. Media Ethics Beyond Borders: A Global Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, Claire. 2017. “Fake News.” It’s Complicated. Available online: https://medium.com/1st-draft/fake-newsits-complicated-d0f773766c79 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, vol. 27, pp. 1–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg, Chloe, and Adam J. Berinsky. 2020. Misinformation and its correction. In Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform. Edited by Nathaniel Persily and Joshua A. Tucker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 163–98. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2024. Global Risks Report. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2024/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- World Health Organisation. 2024. Disinformation and Public Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/disinformation-and-public-health (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- World Health Organization. 2020. 1st WHO Infodemiology Conference. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/epi-win/infodemic-management/infodemiology-scientific-conference-booklet_f7d95516-24e5-414c-bfd2-7a0fc4218659.pdf?sfvrsn=179de76a_4 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Wu, Liang, Fred Morstatter, Kathleen M. Carley, and Huan Liu. 2019. Misinformation in social media: Definition, manipulation, and detection. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 21: 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Xizhu, Porismita Borah, and Yan Su. 2021. The dangers of blind trust: Examining the interplay among social media news use, misinformation identification, and news trust on conspiracy beliefs. Public Understanding of Science 30: 977–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, Adrian K. 2023. Information deprivation and democratic engagement. Philosophy of Science 90: 1110–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Jing, and Scott Babwah Brennen. 2023. Misinformation. Internet Policy Review 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Lina, and Dongsong Zhang. 2007. An ontology-supported misinformation model: Toward a digital misinformation library. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics—Part A: Systems and Humans 37: 804–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).