Moral Judgment and Social Critique in Journalistic News Satire

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. News Satire and Social Critique

1.2. Moral Foundation Theory and the Sweden/US Contexts

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

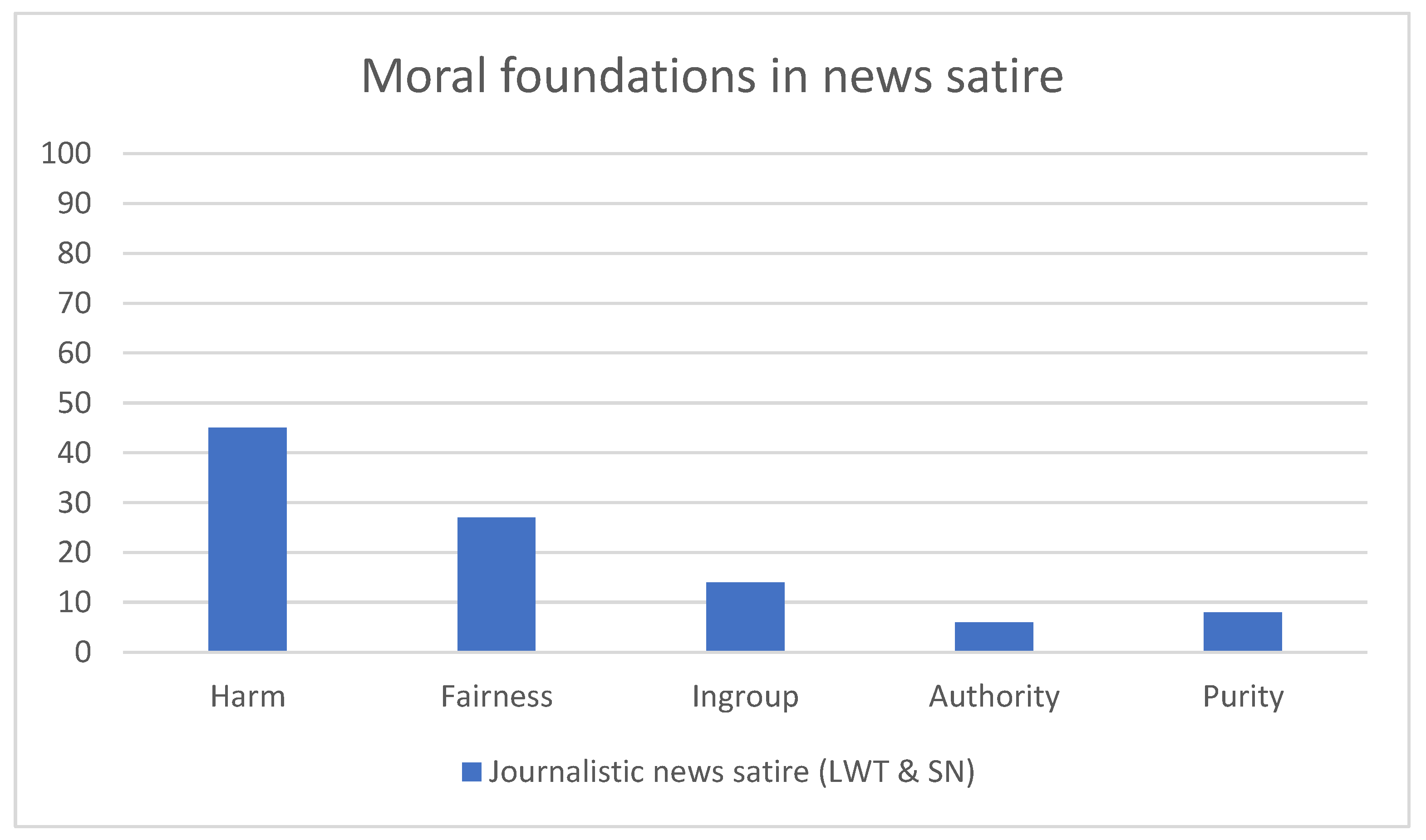

3.1. Overview

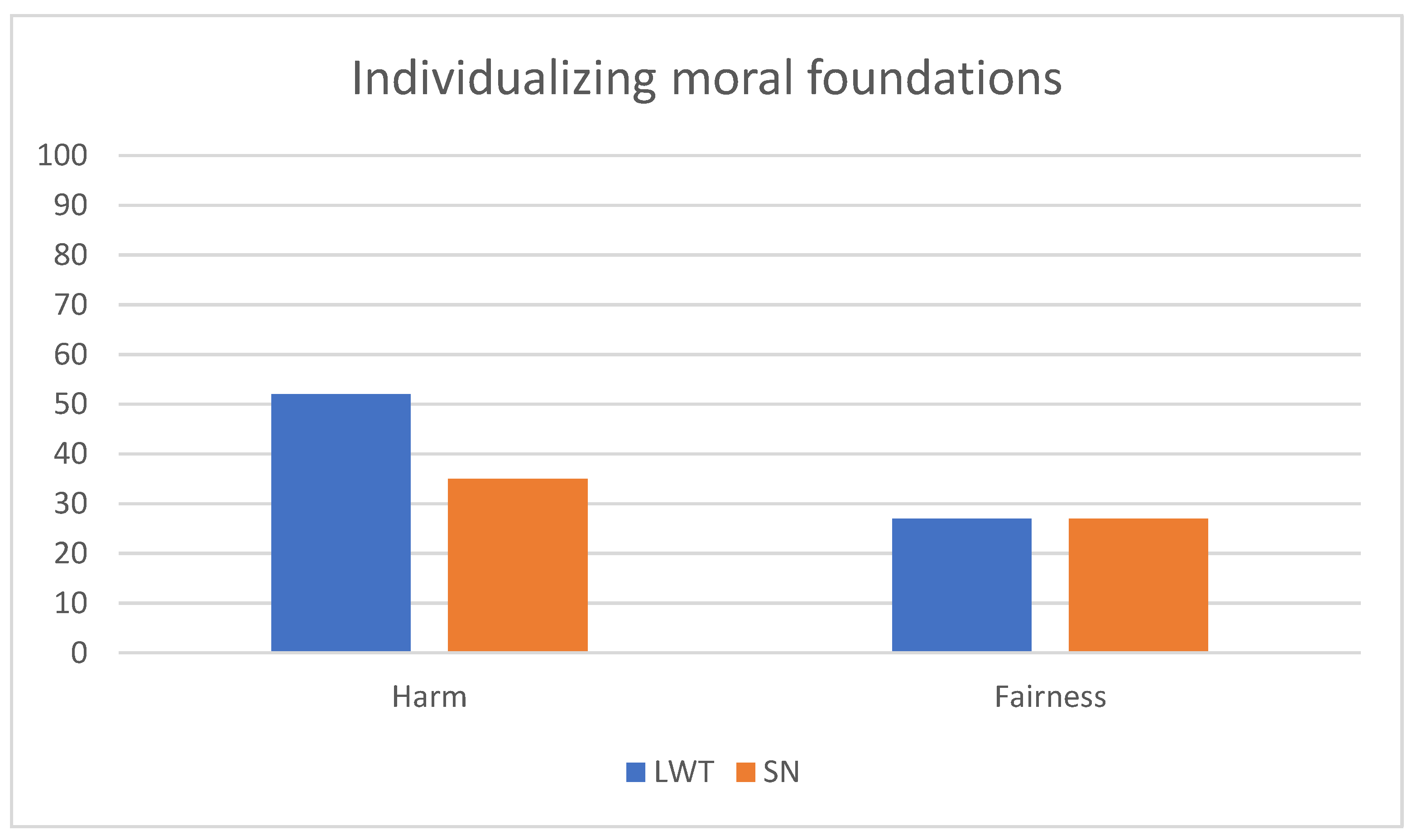

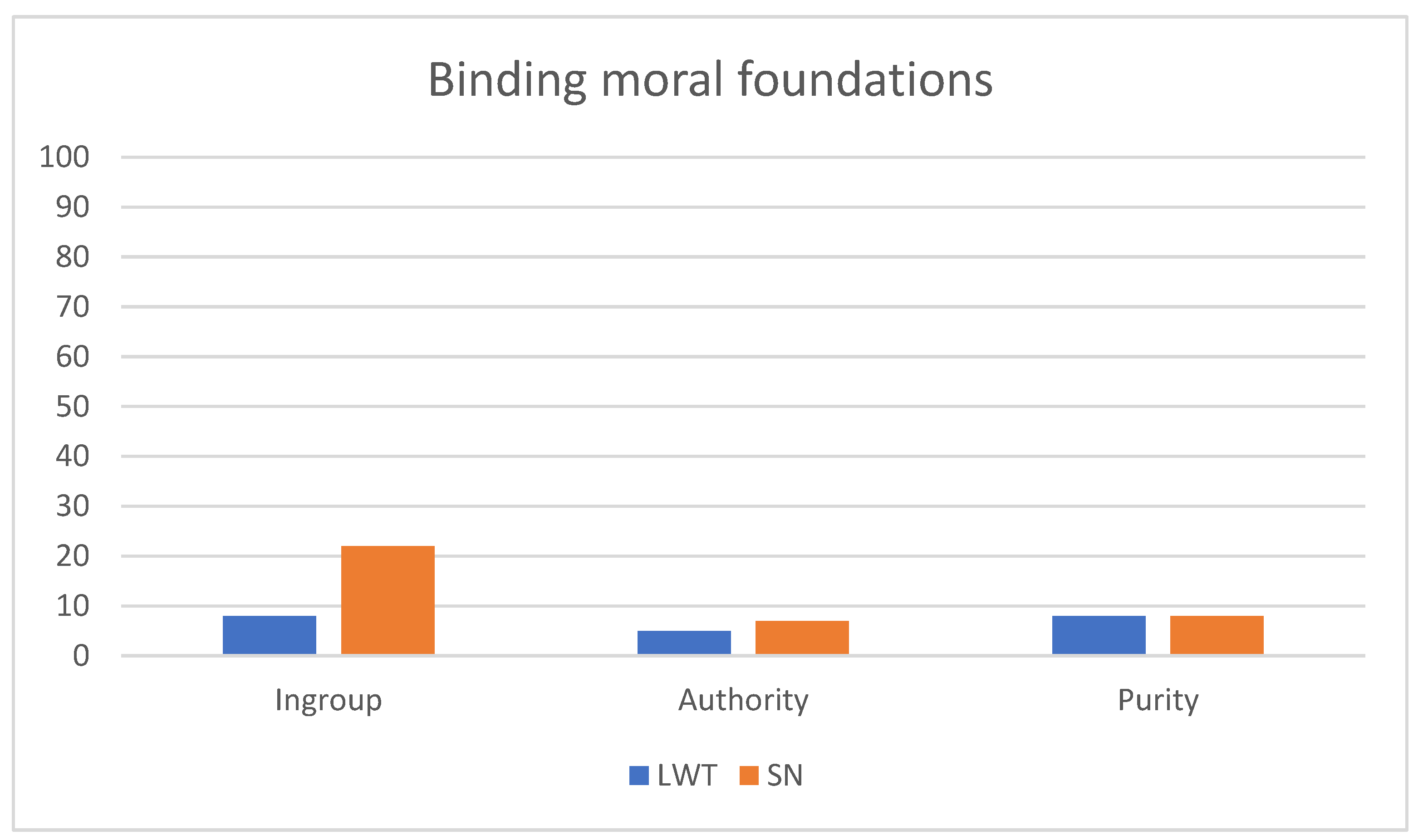

3.2. A Closer Look

I do get the broad worries about how sending money to Afghanistan might inadvertently help the Taliban, but I’d argue the key question here isn’t just “What happens if we send Afghanistan money and aid?” It’s: What happens if we don’t? And we know the answer to that: millions of innocent Afghans will suffer and die under a government they did not choose. The reality is, there is no one simple solution here that is without risks. But 38 million people’s lives are at stake.(LWT, 14 August 2022)

While we managed to get roughly 80,000 Afghans, many of whom had worked with the U.S., to America since the withdrawal, the number who remain in danger because of the association with the U.S. mission can be counted in the hundreds of thousands. So, criticism of what happened is completely justified.(LWT, 14 August 2022)

(graphics display photo of Louise Erixon, the Sweden Democrats). She was happy, cause the Sweden Democrats got nearly 39 percent of the vote down there. (In a history documentarian voice): “The woman in the photo has extended her mandate, in a few days’ time, she will be deceived by her allies, but of this she knows nothing.” You see, the Moderates Kith Mårtensson dumped the Sweden Democrats and replaced them with the Social Democrats.(SN, 28 October 2022)

No. No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no! Never say that again! That may have been the single grossest thing I have ever heard come out of Joe Biden’s mouth, and that is saying a lot, cause I have heard the stuff he used to say in the 1970:s.(LWT, 24 July 2022)

Personally, I get most upset when these—glue sticks, frankly speaking—attack our cultural treasures. ... How low, how incredibly low to include the masterpiece Primavera by Botticelli in this. How much does it even cost to repair the damage after such an attack? Well, it cost some window cleaning because there is apparently protective glass in front… protective glass! (Laughing)(SN, 2 September 2022)

The point is that conversation should be led by the groups that those items originally belong to because while obviously museums should not be violating the law, they shouldn’t be violating basic moral decency either. There is so much that we need to do to reckon with the harms—both past and present—of colonialism, but this should really be the easy part.(LWT, 2 October 2022)

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrams, Meyer Howard, and Geoffrey Harpham. 2008. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Belmont: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Altheide, David L. 1987. Reflections: Ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociology 10: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheide, David L., and Christopher J. Schneider. 2012. Qualitative Media Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Apte, Mahadev L. 1985. Humor and Laughter: An Anthropological Approach. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aylott, Nicholas, and Niklas Bolin. 2023. A new right: The Swedish parliamentary election of September 2022. West European Politics 46: 1049–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, Geoffrey. 2005. The Daily Show: Discursive Integration and the Reinvention of Political Journalism. Political Communication 22: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, Michael. 2005. Laughter and Ridicule: Towards a Social Critique of Humour. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bogel, Fredric V. 2001. A Theory of Satiric Rhetoric. In The Difference Satire Makes. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 41–83. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, William J., Ana P. Gantman, and Jay J. Van Bavel. 2020. Attentional capture helps explain why moral and emotional content go viral. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 149: 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugman, Britta C., Christian Burgers, Camiel J. Beukeboom, and Elly A. Konijn. 2021. From The Daily Show to Last Week Tonight: A Quantitative Analysis of Discursive Integration in Satirical Television News. Journalism Studies 22: 1181–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugman, Britta C., Christian Burgers, Camiel J. Beukeboom, and Elly A. Konijn. 2023. Frame Repertoires at the Genre Level: An Automated Content Analysis of Character, Emotional, and Moral Framing in Satirical and Regular News. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 67: 90–111. [Google Scholar]

- Buchtel, Emma E., Yanjun Guan, Qin Peng, Yanjie Su, Biao Sang, Sylvia Xiaohua Chen, and Michael Harris Bond. 2015. Immorality East and West:Are Immoral Behaviors Especially Harmful, or Especially Uncivilized? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41: 1382–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, Amanda, and Paul Atkinson. 1996. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Critchley, Simon. 2002. On Humour. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett, Molly J. 2017. Moral outrage in the digital age. Nature Human Behaviour 1: 769–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, John Magnus Ragnhildsson. 2021. Voices on the Border: Comedy and Immigration in the Scandinavian Public spheres. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Martin V., Susan T. Fiske, Emily L. Downing, and Thomas E. Trail. 2014. Shifting Liberal and Conservative Attitudes Using Moral Foundations Theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40: 1559–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doona, Joanna. 2020. News satire engagement as a transgressive space for genre work. International Journal of Cultural Studies 24: 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, Allison, Ron Tamborini, Matthew Grizzard, Robert Lewis, Rene Weber, and Sujay Prabhu. 2014. Repeated exposure to narrative entertainment and the salience of moral intuitions. Journal of Communication 64: 501–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamson, Thomas, and H. Clark Barrett. 2008. The encryption theory of humor: A knowledge-based mechanism of honest signaling. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology 6: 261–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Julia R. 2018. Journalist or Jokester? In Political Humor in a Changing Media Landscape: A New Generation of Research. 29 vols. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Sam, and Giselinde Kuipers. 2013. The Divisive Power of Humour: Comedy, Taste and Symbolic Boundaries. Cultural Sociology 7: 179–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimer, Jeremy A., Reihane Boghrati, Jonathan Haidt, Jesse Graham, and Morteza Dehgani. 2019. Moral foundations dictionary for linguistic analyses 2.0. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gantman, Ana P., and Jay J. Van Bavel. 2014. The moral pop-out effect: Enhanced perceptual awareness of morally relevant stimuli. Cognition 132: 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graefer, Anne, Allaina Kilby, and Inger-Lise Kalviknes Bore. 2019. Unruly women and carnivalesque countercontrol: Offensive humor in mediated social protest. Journal of Communication Inquiry 43: 171–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Jesse, Jonathan Haidt, and Brian A Nosek. 2009. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96: 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Jesse, Jonathan Haidt, Sena Koleva, Matt Motyl, Ravi Iyer, Sean P. Wojcik, and Peter H. Ditto. 2013. ‘Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Grizzard, Matthew, Allison Z. Shaw, Emily A. Dolan, Kenton B. Anderson, Lindsay Hahn, and Sujay Prabhu. 2017. Does Repeated Exposure to Popular Media Strengthen Moral Intuitions?: Exploratory Evidence Regarding Consistent and Conflicted Moral Content. Media Psychology 20: 557–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundelach, Peter. 2000. Joking Relationships and National Identity in Scandinavia. Acta Sociologica 43: 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, Jonathan. 2007. The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science 316: 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, Jonathan, and Craig Joseph. 2004. Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus 133: 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, Nicholas. 2023. The limits of satire, or the reification of cultural politics. Thesis Eleven 174: 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheon, Linda. 2003. Irony’s Edge: The Theory and Politics of Irony. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson, Francis. 1725. Reflections upon laughter. The Dublin Weekly Journal, June 19. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson, Peter, Johan Lindell, and Fredrik Stiernstedt. 2021. A Neoliberal Media Welfare State? The Swedish Media System in Transformation. Javnost—The Public 28: 375–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilby, Allaina. 2018. Provoking the Citizen. Journalism Studies 19: 1934–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivukoski, Joonas, and Sara Ödmark. 2020. Producing Journalistic News Satire: How Nordic Satirists Negotiate a Hybrid Genre. Journalism Studies 21: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, Giselinde. 2011. The politics of humour in the public sphere: Cartoons, power and modernity in the first transnational humour scandal. European Journal of Cultural Studies 14: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, Giselinde. 2015. Good Humor, Bad Taste: A Sociology of the Joke. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Laineste, Liisi. 2020. “Zero Is Our Quota” Folkloric Narratives of the Other in Online Forum Comments. In Folklore and Social Media. Edited by Andrew Peck and Trevor J. Blank. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- LaMarre, Heather L., Kristen D. Landreville, and Michael A. Beam. 2009. The Irony of Satire. The International Journal of Press/Politics 14: 212–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht, Caroline V. 2023. Nightly News or Nightly Jokes? News Parody as a Form of Political Communication: A Review of the Literature. Political Studies Review 21: 390–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Paul. 2006. Cracking Up: American Humor in a Time of Conflict. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipson, David, Mark Boukes, and Samira Khemkhem. 2023. The glocalization of The Daily Show. Popular Communication, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Paredes, Marco, and Andrea Carrillo-Andrade. 2022. The Normative World of Memes: Political Communication Strategies in the United States and Ecuador. Journalism and Media 3: 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Ashley. 2013. The Practice of Satire in England, 1658–1770. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Nick, and Matt Sienkiewicz. 2018. The Comedy Studies Reader. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- McClennen, Sophie, and Remy Maisel. 2016. Is Satire Saving Our Nation? Mockery and American Politics. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, Denis. 2003. Media Accountability and Freedom of Publication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, Matthew R., and Casey R. Schmitt, eds. 2016. Standing Up, Speaking Out: Stand-Up Comedy and the Rhetoric of Social Change, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud Wild, Nickie. 2019. “The Mittens of Disapproval Are On”: John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight as Neoliberal Critique. Communication, Culture and Critique 12: 340–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral Foundations Questionnaire. 2008. Available online: https://moralfoundations.org/questionnaires/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Neumann, Dominik, and Nancy Rhodes. 2023. Morality in social media: A scoping review. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaï, Jonas, Pieter Maeseele, and Mark Boukes. 2022. The “Humoralist” as Journalistic Jammer: Zondag met Lubach and the Discursive Construction of Investigative Comedy. Journalism Studies 23: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, Ivo, and Dick Zijp. 2022. The politics and aesthetics of humour in an age of comic controversy. European Journal of Cultural Studies 25: 341–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ödmark, Sara. 2018. Making news funny: Differences in news framing between journalists and comedians. Journalism 22: 1540–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ödmark, Sara. 2021a. De-contextualisation fuels controversy: The double-edged sword of humour in a hybrid media environment. The European Journal of Humour Research 9: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ödmark, Sara. 2021b. Moral Transgressors vs. Moral Entrepreneurs: The Curious Case of Comedy Accountability in an Era of Social Platform Dependence [article]. Journal of Media Ethics 36: 220–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ödmark, Sara, and Jonas Harvard. 2021. The democratic roles of satirists. Popular Communication 19: 281–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedwell, Carolyn. 2017. Mediated habits: Images, networked affect and social change. Subjectivity 10: 147–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifer, Jason, and Taeyoung Lee. 2019. Satire and Journalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peifer, Jason T. 2013. Palin, Saturday Night Live, and Framing: Examining the Dynamics of Political Parody. The Communication Review 16: 155–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, Sophie. 2015. Why Stand-Up Matters How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Rezapour, Rezvaneh, Saumil H. Shah, and Jana Diesner. 2019. Enhancing the Measurement of Social Effects by Capturing Morality. Minneapolis: Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Sagi, Eyal, and Morteza Dehghani. 2013. Measuring Moral Rhetoric in Text. Social Science Computer Review 32: 132–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, Nicole, and Anthony Lioi. 2024. Ecopolitical Satire in the Global North. In The Routledge Handbook of Ecomedia Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Skurka, Chris, Jeff Niederdeppe, and Robin Nabi. 2019. Kimmel on Climate. Science Communication 41: 394–421. [Google Scholar]

- Syvertsen, Trine, Gunn Enli, Ole J. Mjøs, and Hallvard Moe. 2014. The Media Welfare State: Nordic Media in the Digital Era. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tatalovich, Raymond, and Dane G. Wendell. 2018. Expanding the scope and content of morality policy research: Lessons from Moral Foundations Theory. Policy Sciences 51: 565–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test, George A. 1991. Satire: Spirit and Art. Tampa: University of South Florida Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, Sebastián, Martina Piña, and Josefina Ramírez. 2017. Behavioral Effects of Framing on Social Media Users: How Conflict, Economic, Human Interest, and Morality Frames Drive News Sharing. Journal of Communication 67: 803–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, Jay J., Claire E. Robertson, Kareena del Rosario, Jesper Rasmussen, and Steve Rathje. 2023. Social media and morality. Annual Review of Psychology 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadbring, Ingela. 2016. Om dem som tar del av nyheter i lägre utsträckning än andra. In Människorna, medierna & marknaden. Medieutredningens forskningsantologi om en demokrati i förändring. Stockholm: SOU. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Melissa A., and Simon M. Laham. 2016. What We Talk About When We Talk About Morality: Deontological, Consequentialist, and Emotive Language Use in Justifications Across Foundation-Specific Moral Violations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 42: 1206–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, Melissa A., Melanie J. McGrath, and Nick Haslam. 2019. Twentieth century morality: The rise and fall of moral concepts from 1900 to 2007. PLoS ONE 14: e0212267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ödmark, S. Moral Judgment and Social Critique in Journalistic News Satire. Journal. Media 2023, 4, 1169-1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040074

Ödmark S. Moral Judgment and Social Critique in Journalistic News Satire. Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(4):1169-1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖdmark, Sara. 2023. "Moral Judgment and Social Critique in Journalistic News Satire" Journalism and Media 4, no. 4: 1169-1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040074

APA StyleÖdmark, S. (2023). Moral Judgment and Social Critique in Journalistic News Satire. Journalism and Media, 4(4), 1169-1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040074