The Images of Climate Change over the Last 20 Years: What Has Changed in the Portuguese Press?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Potential of Images: Qualities of Visual Content

3. Framing: The Interpretative Frames Offered by the Media and the Importance of Visuals

“Framing is an unavoidable reality of the communication process, especially when applied to public affairs and policy. There is no such thing as unframed information, and the most successful communicators are adept at framing, whether they use framing intentionally or intuitively.”

4. The Role of Images in the Social Construction of Environmental Problems

5. Material and Methods

5.1. Objectives and Research Questions

- What kinds of visual frames are used in the Portuguese press to frame Climate Change? Is there a dominating form of framing?

- Have significant changes in the visual framing of Climate Change been identified over the past two decades of the 21st century?

5.2. Data Collection and Sampling

- National reach: it has a large readership across the country and has the greatest proportion of exclusively digital readers. This makes it a good choice for studying how a particular issue is communicated to a broad audience.

- Editorial policies: A prestige newspaper, like Público, will have consistently maintained well-established editorial policies that guide how news stories are covered and how images are selected. This makes it easier to analyze how the media framing of an issue, such as climate change, evolves over time.

- Comparability: Focusing on a single reference newspaper, we can make meaningful comparisons across different time periods and between different types of news stories. This can help to identify patterns in media framing that may not be apparent when studying multiple newspapers.

- Reputation: Público has a good reputation and is trusted by its readers. In addition, Público launched, in April 2022, a section titled “Azul” that is dedicated to the climate crisis and complex issues related to climate and biodiversity and aims to provide readers with more and deeper keys for reflection on and understanding of the challenges presented by the climate crisis.

5.3. (Visual) Frames Examination

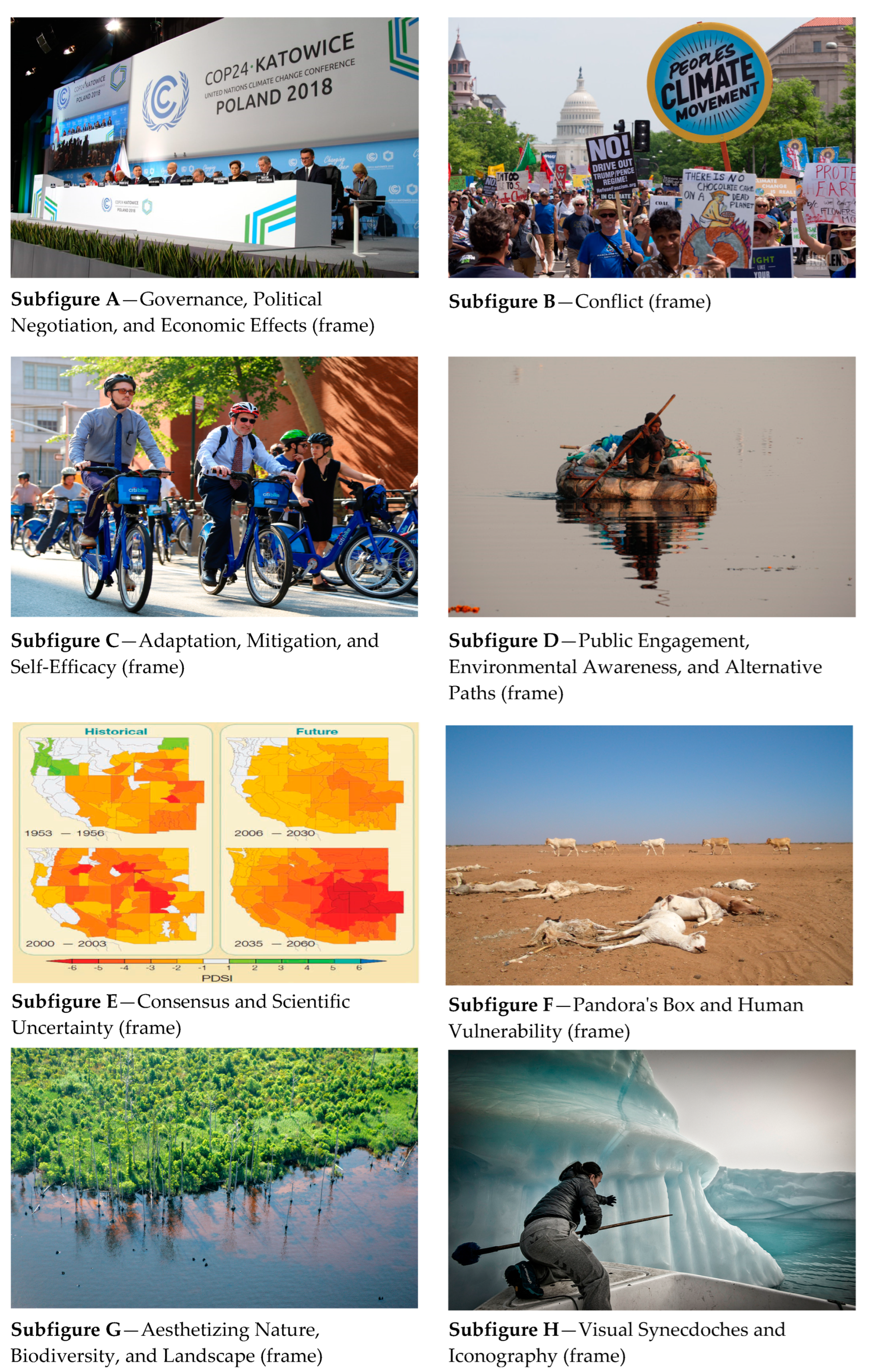

- Subfigure A—Official Opening Ceremony of the Climate Summit COP 24 and Leaders’ Summit in Katowice|UNclimatechange (2018)|Source: Flickr.

- Subfigure B—DC Climate March on 29 April 2017|Mark Dixon (2017)|Source: Climate Visuals (Climate Outreach).

- Subfigure C—Citibikes in New York City|New York City Department of Transportation (2015)|Source: Climate Visuals (Climate Outreach).

- Subfigure D—A man on a makeshift floating platform collecting discarded plastic bags from River Yamuna in Delhi (India)|K Koshi (2007)|Source: Climate Visuals (Climate Outreach).

- Subfigure E—past drought and predictions based on the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI)|U.S. Department of Agriculture|Source: Flickr.

- Subfigure F—Kenya: drought leaves dead and dying animals in northern Kenya|Oxfam International (2004)|Source: Climate Visuals (Climate Outreach).

- Subfigure G—Aerial of too much water at Alligator River|U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters (2009)|Source: Flickr.

- Subfigure H—Greenland, the dilemma of ice: a man and boat push an iceberg through the water so that it does not drag down their fishing nets|Turpin Samuel (2017)|Source: Climate Visuals (Climate Outreach).

6. Results

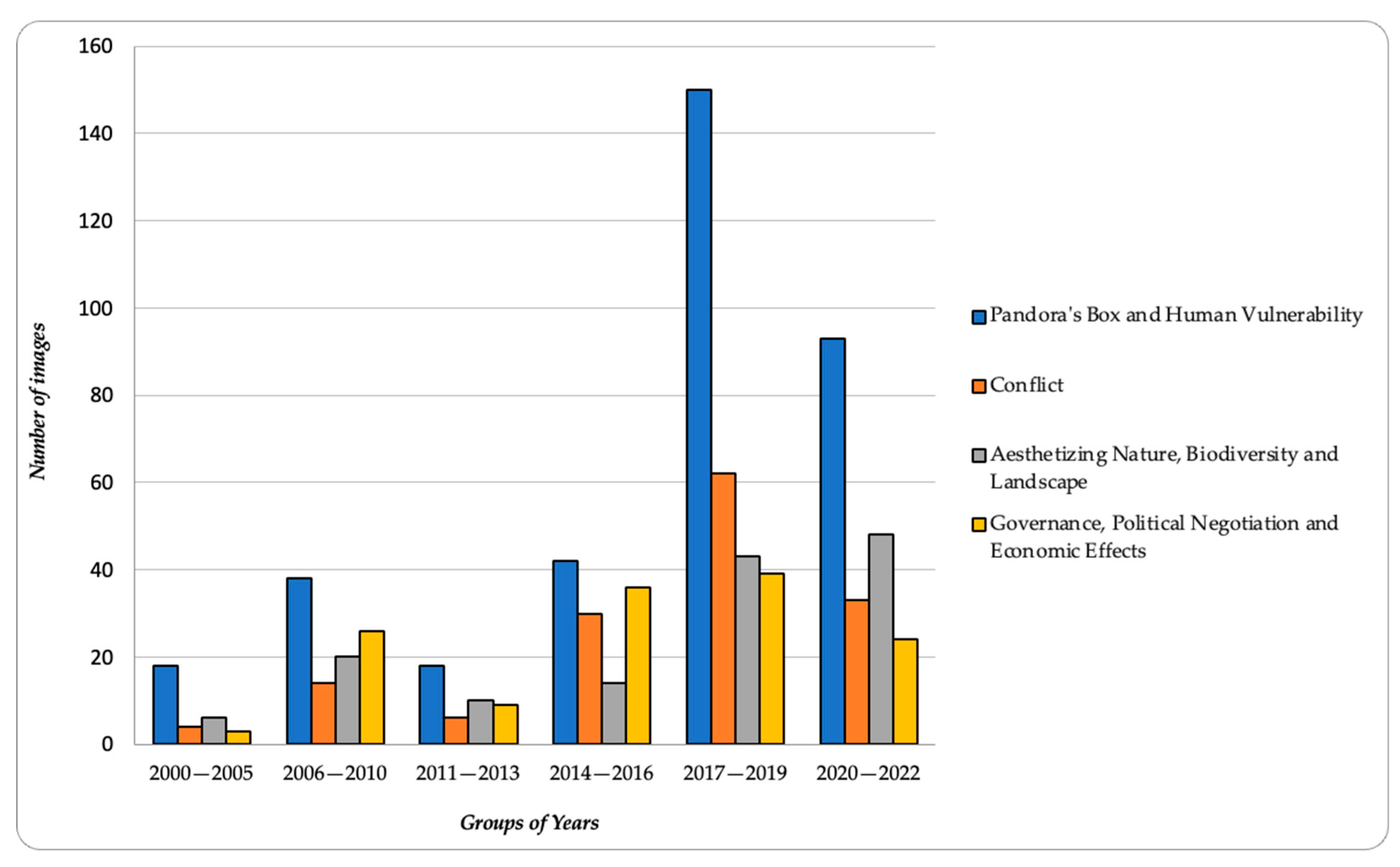

6.1. The Frames That Dominate the Visual Narratives

6.2. The Evolution of the Visual Representation over the Last 20 Years

6.3. The Evolution of Visual Frames over Time

7. Conclusions

7.1. Sensationalist Narrative: Pandora’s Box Frame and Human Vulnerability

7.2. The Politicization of Climate Change and the Idea of Conflict

7.3. Solutions as Visual Framing

7.4. Scientific Knowledge: Searching for a Common Ground

7.5. Aestheticization of Nature and Metamorphosis of the Landscape

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We were unable to share the sample of photographs from the newspaper analysis, mostly because to copyright concerns. From image libraries with creative commons licenses, prototype pictures were chosen that either match or are strikingly similar to those in our sample. So, we can demonstrate the kinds of photos that were taken into account for each of the frames. |

| 2 | Hundreds of emails exchanged between British and American scientists have been accessed and used by climate change deniers to discredit the data, as they “were desperate to find ways to undermine the idea that global warming was real”. Read more at https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2019/nov/09/climategate-10-years-on-what-lessons-have-we-learned, accessed on 13 June 2023. |

References

- Anderson, Alison. 2009. Media, politics and climate change: Towards a new research agenda. Sociology Compass 3: 166–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badullovich, Nic, Will J. Grant, and Rebecca M. Colvin. 2020. Framing climate change for effective communication: A systematic map. Environmental Research Letters 15: 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Philip. 2004. Content Analysis of Visual Images. In The Handbook of Visual Analysis. Edited by Theo Van Leeuwen and Carey Jewitt. London: Sage, pp. 10–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, Leticia, and Emily K. Vraga. 2015. In Related News, That Was Wrong: The Correction of Misinformation through Related Stories Functionality in Social Media. Journal of Communication 65: 619–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, Toby, and Matthew A. Shapiro. 2018. The US News Media, Polarization on Climate Change, and Pathways to Effective Communication. Environmental Communication 12: 149–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, Maxwell. 2019. Creative (Climate) Communications. Productive Pathways for Science, Policy and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, Maxwell T. 2012. Who speaks for the climate? Making sense of media reporting on climate change. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 24: 546–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, David. 2007. Geopolitics and visuality: Sighting the Darfur conflict. Political Geography 26: 357–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Anabela. 2005. Representing the politics of the greenhouse effect: Discursive strategies in the British media. Critical Discourse Studies 2: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, Kris, Emily Coren, Mark McCaffrey, and Cheryl Slean. 2020. Transforming the stories we tell about climate change: From ‘issue’ to ‘action’. Environmental Research Letters 16: 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, Darryn A., and Nathan Young. 2011. Seeing climate change: The visual construction of global warming in Canadian national print media. Cultural Geographies 18: 517–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, Lisa, and Susanne Moser. 2004. Communicating the Urgency and Challenge of Global Climate Change: Lessons Learned and New Strategies. Paper presented at AGU Fall Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, December 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Domke, David, David Perlmutter, and Meg Spratt. 2002. The primes of our times? An examination of the ‘power’ of visual images. Journalism 3: 131–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, Anthony. 1972. Up and down with ecology—The “Issue-Attention cycle”. The Public Interest 28: 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Seymour. 1994. Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist 49: 709–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, Xénia, Daniel Jackson, Pawel Baranowski, Márton Bene, Uta Russmann, and Anastasia Veneti. 2022. Strikingly similar: Comparing visual political communication of populist and non-populist parties across 28 countries. European Journal of Communication 37: 545–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, William A., and Andre Modigliani. 1989. Media Discourse and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power: A Constructionist Approach. American Journal of Sociology 95: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, Deepti. 2022. Media and Climate Change Making Sense of Press Narratives, 1st ed. Delhi: Routledge India. 130p, ISBN 9780367443184. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Sylvia, and Saffron O’Neill. 2021. The Greta effect: Visualising climate protest in uk media and the Getty images collections. Global Environmental Change 71: 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, Hélène. 2008. The Power of Visual Material: Persuasion, Emotion and Identification. Diogenes 55: 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, Betsy, Thompson Jessica, Davis Shawn, and Joshua M. Carlson. 2019. Affective Images of Climate Change. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiserowitz, Anthony. 2006. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Climatic Change 77: 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Bienvenido, and Maria C. Erviti. 2015. Science in pictures: Visual representation of climate change in Spain’s television news. Public Understanding of Science 24: 183–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Bienvenido, Michael Bourk, Wiebke Finkler, Maxwell Boykoff, and Lloyd S. Davis. 2021. Strategies for climate change communication through social media: Objectives, approach, and interaction. Media International Australia 0: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Bienvenido, Samuel Negredo, and Maria C. Erviti. 2022. Social Engagement with climate change: Principles for effective visual representation on social media. Climate Policy 22: 976–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, Libby. 2022. Journalism and Environmental Futures. In The Routledge Companion to News and Journalism. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzoni, Irene, Sophie Nicholson-Cole, and Lorraine Whitmarsh. 2007. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change 17: 445–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusa. 2022. Portugal: Among Worst Hit in Terms of GDP by Extreme Weather Events. Macau News Agency. Available online: https://www.macaubusiness.com/portugal-among-worst-hit-in-terms-of-gdp-by-extreme-weather-events/ (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Maehle, Natalia, Caterina Presi, and Ingeborg Kleppe. 2022. Visual communication in social media marketing. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Marketing. Edited by Annmarie Hanlon and Tracy L. Tuten. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodieva, Aleksandrina, Okky K. Rachman, Vito B. Harahap, and Rajib Shaw. 2019. Role of Social Media as a Soft Power Tool in Raising Public Awareness and Engagement in Addressing Climate Change. Climate 7: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, Susanne C., and Lisa Dilling. 2007. Toward the social tipping point: Creating a climate for change. In Creating a Climate for Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson-Cole, Sophie A. 2005. Representing climate change futures: A critique on the use of images for visual communication. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 29: 255–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, Matthew C. 2010. Communicating Climate Change: Why Frames Matter for Public Engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 51: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, Matthew C., and Mike Huge. 2006. Attention Cycles and Frames in the Plant Biotechnology Debate: Managing Power and Participation through the Press/Policy Connection. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 11: 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Saffron. 2013. Image matters: Climate change imagery in US, UK and Australian newspapers. Geoforum 49: 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Saffron. 2020. More than meets the eye: A longitudinal analysis of climate change imagery in the print media. Climatic Change 163: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Saffron. 2022. Defining a visual metonym: A hauntological study of polar bear imagery in climate communication. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47: 1104–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Saffron, and Sophie Nicholson-Cole. 2009. “Fear Won’t Do It”: Promoting Positive Engagement with Climate Change through Visual and Iconic Representations. Science Communication 30: 355–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Saffron, Maxwell Boykoff, Simon Niemeyer, and Sophie A. Day. 2013. On the use of imagery for climate change engagement. Global Environmental Change 23: 413–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, James, and Teresa Ashe. 2012. Cross-national comparison of the presence of climate scepticism in the print media in six countries, 2007–10. Environmental Research Letters 7: 044005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Warren, Suay M. Özkula, Amanda K. Greene, Lauren Teeling, Jennifer S. Bansard, Janna J. Omena, and Elaine Teixeira Rabello. 2020. Visual Cross-Platform Analysis: Digital methods to research social media images. Information, Communication & Society 23: 161–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, Richard K., and Andrew L. Mendelson. 2010. ‘X’-ing out enemies: Time magazine, visual discourse, and the war in Iraq. Journalism 11: 203–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebich-Hespanha, Stacy, and Ronald E. Rice. 2016. Dominant Visual Frames in Climate Change News Stories: Implications for Formative Evaluation in Climate Change Campaigns. International Journal of Communication 10: 4830–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. 100p, ISBN 9781529783940. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, Mike S., and James Painter. 2020. Climate Journalism in a Changing Media Ecosystem: Assessing the Production of Climate Change-related News around the World. WIREs Clim Change 12: e675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, Mike S., and Inga Schlichting. 2014. Media representations of climate change: A meta-analysis of the research field. Environmental Communication 8: 142–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Andreas, Ana Ivanova, and Mike S. Schäfer. 2013. Media attention for climate change around the world: A comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries. Global Environmental Change 23: 1233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Robert O. 2011. Climate change: An emergency management perspective. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 20: 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Nicholas W., and Hélène Joffe. 2009. Climate change in the British press: The role of the visual. Journal of Risk Research 12: 647–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecula, Dominik A., and Eric Merkley. 2019. Framing Climate Change: Economics, Ideology, and Uncertainty in American News Media Content from 1988 to 2014. Frontiers in Communication 4: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson, Zheng W. Lim, and Richard Ling. 2018. Defining “fake news”: A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism 6: 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibeck, Victoria. 2014. Enhancing learning, communication and public engagement about climate change—Some lessons from recent literature. Environmental Education Research 20: 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2010. Journalism, Memory, and the Voice of the Visual. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Nan, and Marko M. Skoric. 2018. Media Use and Environmental Engagement: Examining Differential Gains from News Media and Social Media. International Journal of Communication 12: 380–403. [Google Scholar]

| Frame | How Climate Change Is Framed |

|---|---|

| Governance, Politics and Negotiation | It reinforces the vision that governments and political agendas are critical to defining and responding to climate change. It is often represented by images of politicians participating in national or international negotiation events. |

| Climate Science, Research and Scientists | It introduces climate science and the scientific community as important agents of definition for the climate change issue. Images often include both photographs of scientists or research material as well as diagrams illustrating aspects of the climate system (e.g., the greenhouse effect). |

| Monitoring and Quantifying | It emphasizes the view that empirical evidence supports the public’s understanding of environmental challenges and potential solutions. Images associated with this frame are frequently graphs, thematic maps, and diagrams. |

| Common People (sometimes vulnerable) | It focuses on humans but gives a multifaceted image of them as the subject of the frame. There are three possible dimensions: the common people who may experience or be vulnerable to the repercussions of CC or political decisions, the people who may be the audience for political, civic, or corporate leaders, and the people who may join in protests, rallies, or other related activities. |

| Industrial impact on the environment | It reinforces industrial development as a major cause of damage to the climate system. In general, the images include photographs and representations of industrial landscapes and smokestacks, for e.g., icons of the environmental destruction caused by industry. |

| Storms | It highlights the association of CC with devastating storms, reinforcing a sense of vulnerability and risk and the need for urgent action in response to the environmental crisis. It implies that the point of no return has already been reached and that it is now too late to act. |

| Impacts on polar animals and landscape | It emphasizes the hazards posed by climate change to polar species and ecosystems. These types of images, such as photographs of polar bears on small ice slabs and melting glaciers, have come to symbolize climate change visually. |

| Frame | How the Issue Is Framed |

|---|---|

| Governance, Political Negotiation, and Economic Effects | Focus on broad national or supranational discussions and debates, public policy-making, and the responsiveness of political institutions; processes such as participation, action, and political decision-making are emphasized; geopolitical conflict, social relations of production, the circulation and distribution of goods, and the economic effects of CC and political action are frequently present. |

| Conflict | Focus on the broad concept of conflict, wherein ideas, sentiments, or interests collide; conflict can be politicized with the mobilization of activist groups that speak out against the status quo and demand political and economic measures to address the issue; on the other hand, human–nature conflict is enhanced by the excessive consumption of natural resources and by a mechanistic view of nature on the human part. |

| Adaptation, Mitigation, and Self-Efficacy | Focus on self-efficacy and climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies; self-efficacy focuses on behavioral changes (individual or group-based) and the adoption of sustainable habits, and can also focus on external efficacy, which refers to the responsiveness of business leaders or high-level social figures; this type of framework also addresses the replacement of fossil fuels and the related aspects of energy transition. |

| Public Engagement, Environmental Awareness, and Alternative Paths | Focus on public engagement, promoting environmental literacy through educational mechanisms and alternative paths that attempt to be in balance with, rather than dominate, nature; it highlights, sometimes, a human narrative from a common citizen or the collective action of a local community; it explores the moral and ethical issues that drive action to tackle climate change. |

| Consensus and Scientific Uncertainty | Focus on the discussion between scientific statements and the uncertainties regarding causality relations; on the one hand, it tries to argue in favor of a generalized consensus of the scientific community, and on the other hand, it highlights the uncertainties regarding the complexity of the phenomenon of CC; the double issue of monitoring and quantification is also added, which reinforces the debate using graphics, thematic maps, and other visual representations. |

| Pandora’s Box and Human Vulnerability | Focus on the need for precaution and action against possible disasters and the dramatizing of the effects of CC, reinforcing a sense of fear, vulnerability, or inability to deal with the problem; it focuses on devastating storms, the environmental devastation caused by industry, and the severe effects that result from climate change such as air pollution, environmental disasters, fires, and the extinction of species; in any of the scenarios, humanity breaks down against the challenge it faces. There is also an implicit dimension of future impact, with the demonstration of unmanageable consequences and the release of severe effects. |

| Aesthetizing Nature, Biodiversity, and Landscape | Focus on the romantic view of nature and the poetic image of biodiversity, appealing to the empathetic relationship of the viewer with a beautiful nature in danger of extinction; this framing promotes self-awareness and reflection, highlighting the eventual absence of a landscape that once pleased the viewer or the beauty of animals facing the risk of extinction. |

| Visual Synecdoches and Iconography | Focus on images that often serve as visual portrayals to represent CC and have been established, over the years, as visual shortcuts used to convey a message that is immediately understood by the viewer. In this frame we consider only the images of polar bears, polar icecaps, and glaciers, assigning other frames to icons such as smokestacks for their relevance in terms of visual meaning. A visual synecdoche encapsulates the impacts of climate change on, for e.g., polar bears as an illustration of the much wider impacts of climate change (O’Neill 2022). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopes, L.S.; Azevedo, J. The Images of Climate Change over the Last 20 Years: What Has Changed in the Portuguese Press? Journal. Media 2023, 4, 743-759. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030047

Lopes LS, Azevedo J. The Images of Climate Change over the Last 20 Years: What Has Changed in the Portuguese Press? Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(3):743-759. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030047

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Leonardo Soares, and José Azevedo. 2023. "The Images of Climate Change over the Last 20 Years: What Has Changed in the Portuguese Press?" Journalism and Media 4, no. 3: 743-759. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030047

APA StyleLopes, L. S., & Azevedo, J. (2023). The Images of Climate Change over the Last 20 Years: What Has Changed in the Portuguese Press? Journalism and Media, 4(3), 743-759. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030047