The Construction of Peacebuilding Narratives in ‘Media Talk’—A Methodological Discussion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Media, Narratives and Peacebuilding

2.1. Media and Peacebuilding

(…) glorify or puncture the images of the parties of a conflict, infuse optimistic or pessimistic impressions about the possibilities of peace, fortify or undermine the public’s willingness to compromise, and buttress or render hollow the legitimacy of the protagonists in a conflict including the state.

2.2. Narratives in Media Talk

3. A Social Constructionist Perspective in Narrative Approach

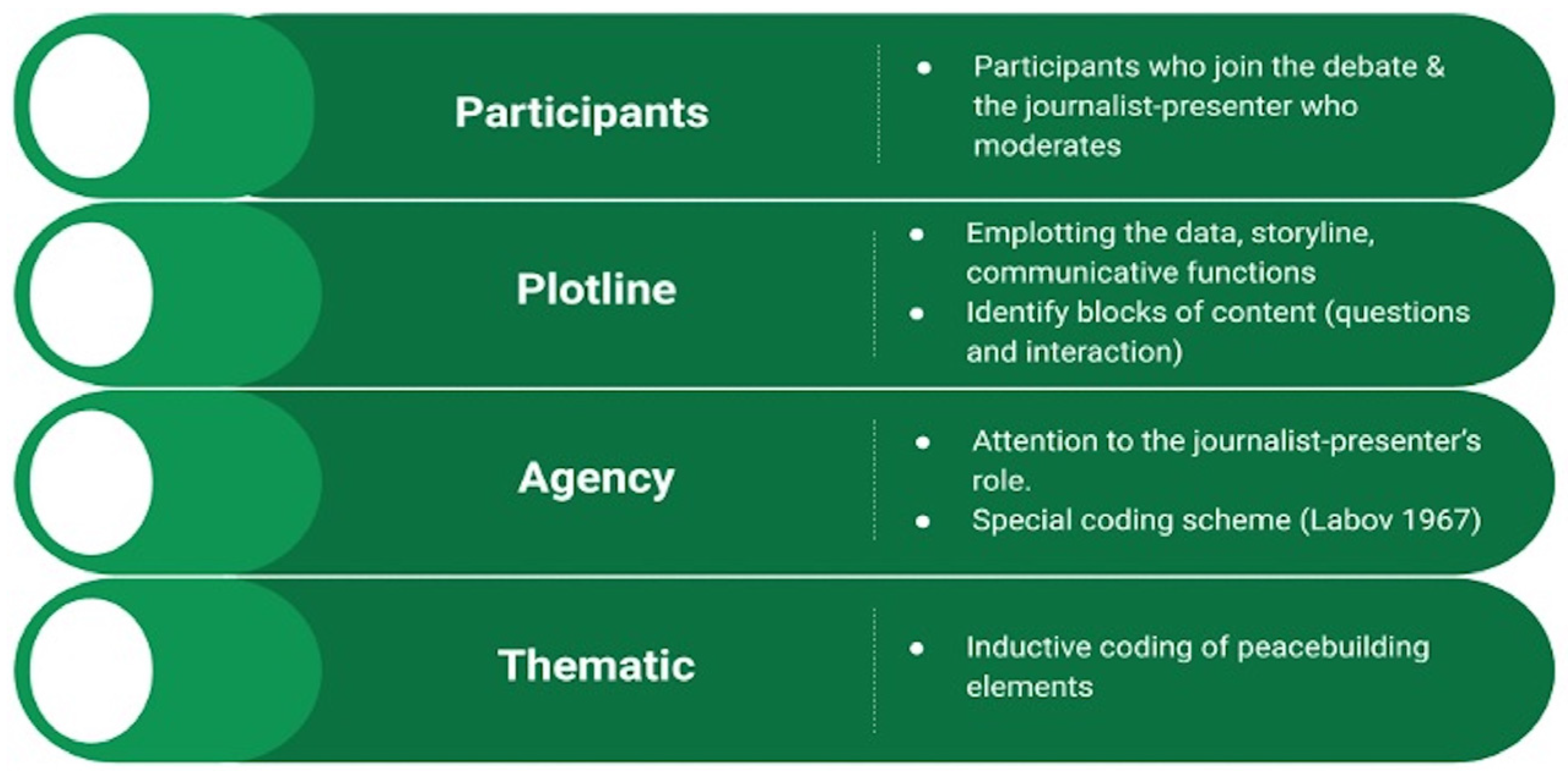

4. A Framework for Interpretative Narrative Analysis

4.1. Actors (Participants) Dimension

4.2. Plotline or Structural Dimension

- Abstract: a summary of the story and its points.

- Orientation: providing a context such as place, time and character to orient.

- Complicating Action: skeleton plot, or an event that causes a problem as in ‘And then what happened?’.

- Evaluation: evaluative comments on events, justification of its telling or the meaning that the teller gives to an event.

- Result or Resolution: resolution of the story or the conflict; it follows the evaluation.

- Coda: bringing the narrator and listener back to the present; it is a functional device for returning the verbal perspective to the present moment.

4.3. Agency Dimension

4.4. Thematic Dimension

5. Case Report ‘Patara’: Media Talk in Radio

“We debate the subjects concerning the political life in Central Africa, the subjects that marked the week. It is a political debate, but we touch all the sensitive questions in the society. We question the ruling power. The programme is very civic.”

6. Operationalising the Coding System

6.1. STEP I. Identifying and Locating Participants

[Présentatrice] Selon vous la solution pour ramener la paix définitivement en République centrafricaine passera nécessairement par Khartoum?(PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 74–75)10

[Présentatrice] Alors, les groupes armés avaient publié des revendications, et parmi ces revendications, il y en a douze qui sont non négociables dont, l’amnistie générale. (…) Vous confirmez les douze revendications non negociables?(PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 78–84)11

6.2. STEP II. Identifying the Structure or Plotline of the Program

6.2.1. The Journalist-Presenter

6.2.2. Blocks of Content

6.2.3. Communicative Functions

6.3. STEP III. Identifying Levels of Agency

6.3.1. Scrutinising the Presenter’s Role

[Présentatrice] Merci Monsieur, Albert Mbaya, le gouvernement qui ne contrôle que Bangui et quelques préfectures ferait le poids devant ceux qui tiennent la grande partie du pays?(PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 145–46)13

6.3.2. Agency Codes

[Présentatrice]/Oui, je reviens à la société civile, est-ce que cette société civile était l’invitée à Khartoum?(PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 92–93)14

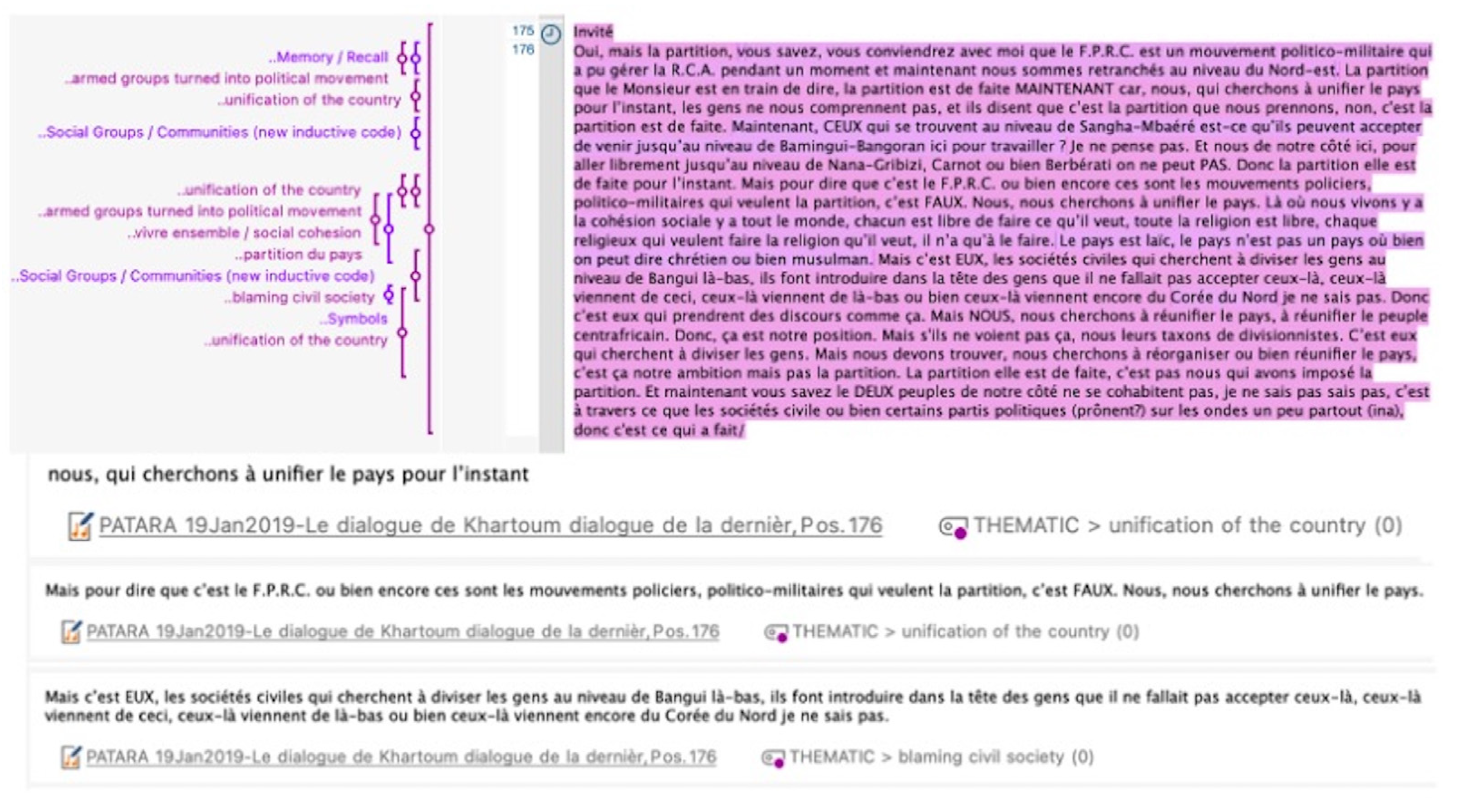

6.4. STEP IV. Identifying Thematic Codes

7. A Brief Discussion

8. Concluding Remarks: Detecting Emerging Narratives

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic was a 1350-troop peacekeeping mission established by the UN Security Council in March 1998 and lasted until February 2000. |

| 2 | The Fund was created by France, Germany and the Netherlands and was later joined by Italy and Switzerland. Bêkou means ‘hope’ in Sango. |

| 3 | Interview conducted online on 16 March 2021. The interviews portrayed in this article serve mainly the purpose to offer context and background information about the radio itself and its programme. Following the ethical and informed consent, the names of the interviewees are kept in confidentiality. The interviews were conducted by the researcher in an extensive fieldwork data collection throughout 2021. |

| 4 | Interview conducted online on 25 May 2021. |

| 5 | The crisis in CAR was marked by a coup d’état (March 2013) perpetrated by a majorly Muslim armed coalition named Seleka (‘alliance’ in Sango) that invaded and conquered many towns from the northern part of the country and marched towards the capital Bangui to overthrow the president, at that time, François Bozizé. A further counterattack in December 2013 by a mainly Christian militia, named anti-Balaka, immersed the country into widespread violence. |

| 6 | Interview conducted online on 24 February 2021. |

| 7 | Online interview with Radio Ndeke Luka former editor-in-chief in 24 February 2021. |

| 8 | Political Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in the Central African Republic. |

| 9 | Following the Brazzaville ceasefire conference of July 2014 and the CAR popular consultations during the first quarter of 2015, the forum resulted in the adoption of a Republican Pact for Peace, National Reconciliation and Reconstruction in the CAR and the signature of a Disarmament, Demobilisation, Rehabilitation and Repatriation (DDRR) agreement among 9 of 10 armed groups (UN News 2015). It produced 643 recommendations out of these meetings that were mainly within the framework of good governance, justice, peace, national reconciliation, security and socio-economic development (Ndeke Luka 2020). |

| 10 | [Presenter] In your opinion, will the solution to definitively bring peace to the Central African Republic necessarily go through Khartoum? (PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 74–75). Translation into English. |

| 11 | [Presenter] So the armed groups had published demands, and among these demands, there are twelve that are non-negotiable, including general amnesty. (…) Do you confirm the twelve non-negotiable demands? (PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 78–84). Translation into English. |

| 12 | Original title in French ‘Mon pays va mal’. |

| 13 | [Presenter] Thank you sir Albert Mbaya, the government that controls only Bangui and a few prefectures would be a match for those who control most of the country? (PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 145–46). Translation into English. |

| 14 | [Presenter]/Yes, I come back to the civil society, was the civil society the guest in Khartoum? (PATARA 19 January 2019, Pos. 92–93). Translation into English. |

References

- Abkhezr, Peyman, Mary McMahon, Marilyn Campbell, and Kevin Glasheen. 2020. Exploring the Boundary between Narrative Research and Narrative Intervention: Implications of Participating in Narrative Inquiry for Young People with Refugee Backgrounds. Narrative Inquiry 30: 316–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, Laura M. 1999. Agency. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 9: 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartesaghi, Mariaelena, and Theresa Castor. 2008. Social Construction in Communication Re-Constituting the Conversation. Annals of the International Communication Association 32: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Philip, and Theo van Leeuwen. 1994. The Media Interview: Confession, Contest, Conversation. Kensington: University of New South Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, Michelle. 2012. Conflict Sensitive Journalism: Moving towards a Holistic Framework. Denmark: IMS. Available online: https://www.mediasupport.org/publication/conflict-sensitive-journalism-moving-towards-a-holistic-framework/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Björninen, Samuli, Mari Hatavara, and Maria Mäkelä. 2020. Narrative as Social Action: A Narratological Approach to Story, Discourse and Positioning in Political Storytelling. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 23: 437–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräuchler, Birgit, and Philipp Naucke. 2017. Peacebuilding and Conceptualisations of the Local. Social Anthropology 25: 422–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruck, Peter, and Colleen Roach. 1993. Communication and Culture in War and Peace. In Communication and Culture in War and Peace. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budka, Philipp, and Birgit Bräuchler, eds. 2020. Theorising Media and Conflict. Anthropology of Media. New York: Berghahn Books, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, Vivien. 1995. An Introduction to Social Constructionism. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, Vivien. 2003. Social Constructionism, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Figueras, Blanca, Blanca Calvo Figueras, Tommaso Caselli, and Marcel Broersma. 2022. Finding Narratives in News Flows: The Temporal Dimension of News Stories. Digital Humanities Quarterly 15: 15. Available online: http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/15/4/000582/000582.html# (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Certeau, Michel de. 1992. The Writing of History. Translated by Tom Conley. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, Sara. 1993. Empowerment and Mediation: A Narrative Perspective. Negotiation Journal 9: 245–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, Patrick. 2003. Paul Ricœur: The Concept of Narrative Identity, the Trace of Autobiography. Paragraph 26: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Devon E. A. 2000. Broadcasting Peace: An Analysis of Local Media Post-Conflict Peacebuilding Projects in Rwanda and Bosnia. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement 21: 141–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Anne. 2005. Radio News and Interviews. In Narrative and Media. Edited by Helen Fulton, Rosemary Huisman, Julian Murphet and Anne Dunn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 203–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Ann Mische. 1998. What Is Agency? American Journal of Sociology 103: 962–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, Beste Nigar. 2019. The Construction of the Social Reality from the News Narrative to Transmedia Storytelling: A Research on the Masculine Violence and the Social Reflexes. In Handbook of Research on Transmedia Storytelling and Narrative Strategies. Edited by Recep Yılmaz, M. Nur Erdem and Filiz Resuloğlu. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, Richard Victor, Patricia M. Baranek, and Janet B. L. Chan. 1991. Representing Order: Crime, Law, and Justice in the News Media. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esin, Cigdem, Mastoureh Fathi, and Corinne Squire. 2014. Narrative Analysis: The Constructionist Approach. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Edited by Uwe Flick. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. n.d. Bêkou Trust Fund. Text. International Partnerships—European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/programmes/bekou-trust-fund_en (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Foster, Elissa, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2008. Social Constructionist Perspectives in Communication Research. In Handbook of Constructionist Research. Edited by James A. Holstein and Jaber F. Gubrium. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Frère, Marie-Soleil, and Jean-Paul Marthoz. 2007. The Media and Conflicts in Central Africa. Boulder: Lynne Reinner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, Johan. 2002. Peace Journalism—A Challenge. In Journalism and the New World Order. Edited by Wilhelm Kempf and Heikki Luostarinen. Sweden: Nordicom, vol. 2, pp. 259–72. Available online: https://www.nordicom.gu.se/en/publikationer/journalism-and-new-world-order-vol2 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Galtung, Johan. 2003. Peace Journalism. Media Asia 30: 177–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtung, Johan, C. G. Jacobsen, and Kai Frithjof Brand-Jacobsen. 2002. Searching for Peace: The Road to Transcend, 2nd ed. Peace by Peaceful Means. London and Sterling: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garagozov, Rauf. 2015. How to Construct a Common Narrative from among the Competing Accounts: Narrative Templates as Cultural Limiters to Narrative Transformations. Narrative and Conflict: Explorations in Theory and Practice 2: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergen, Kenneth. 2001. Social Construction in Context. London: Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grbich, Carol. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction, 2nd ed. London and Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Anders, and David Machin. 2013. Media and Communication Research Methods. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, Rosa. 2018. Storytelling Agents: Why Narrative Rather than Mental Time Travel Is Fundamental. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 17: 535–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Julia, and Virgil Hawkins, eds. 2015. Communication and Peace: Mapping an Emerging Field. Routledge Studies in Peace and Conflict Resolution. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Ross. 2004. Conflict Sensitive Journalism. Denmark: Institute for Media, Policy and Civil Society (IMPACS), International Media Support (IMS). Available online: https://www.mediasupport.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/ims-csj-handbook-2004.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Howard, Ross. 2009. Conflict-Sensitive Reporting: State of the Art—A Course for Journalists and Journalism Educators. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman, Rosemary, Julian Murphet, and Anne Dunn. 2005. Narrative and Media. Edited by Helen Fulton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchby, Ian. 2006. Media Talk: Conversation Analysis and the Study of Broadcasting. Issues in Cultural and Media Studies. Maidenhead and New York: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- IMMAR. 2017. Mesure d’Audience RCA—TV & Radio. Audience research commissioned by Fondation Hirondelle. Unpublished work. 52p. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Iqani, Mehita, and Fernando Resende. 2019. Theorizing Media in and across the Global South: Narrative as Territory, Culture as Flow. In Media and the Global South. London: Routledge, pp. 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kappler, Stefanie. 2014. Local Agency and Peacebuilding—EU and International Engagement in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Cyprus and South Africa. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jeong-Hee. 2015. Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The Crafting and Analysis of Stories as Research, 1st ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William, and Joshua Waletzky. 1967. Narrative Analysis: Oral Versions of Personal Experience. In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts, Proceedings of the 1966 Annual Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society. Seattle: Univrsity of Washington Press, pp. 12–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach, John Paul. 1997. Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington: United States Institute of Peace Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindlof, Thomas R. 2008. Constructivism. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Edited by Wolfgang Donsbach. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, vol. 3, pp. 944–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindlof, Thomas R., and Bryan C. Taylor. 2019. Qualitative Communication Research Methods, 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lugalambi, George W. 2006. Media, Peace-Building and the Culture of Violence. In Media in Situations of Conflict: Roles Challenges and Responsibility. Edited by Adolf E. Mbaine. Kampala: African Books Collective, pp. 103–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Jake, and Annabel McGoldrick. 2005. Peace Journalism. Stroud: Hawthorn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Jake, and Annabel McGoldrick. 2012. Responses to Peace Journalism. Journalism 14: 1041–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Ginty, Roger. 2015. Where is the local? Critical localism and peacebuilding. Third World Quarterly 36: 840–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Ginty, Roger, ed. 2013. Routledge Handbook of Peacebuilding. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mankou, Serge Patrick, and Samuel Thierry Nzam. 2017. RCA: Le MLCJ Attend des réponses à ses Revendications. Africanews. June 6. Available online: https://fr.africanews.com/2017/06/06/rca-le-mlcj-attend-des-reponses-a-ses-revendications/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Mano, Winston. 2021. Peace and Conflict Journalism: An African Perspective. In Insights on Peace and Conflict Reporting. Edited by Kristin Skare Orgeret. London: Routledge, pp. 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Maweu, Jacinta, and Admire Mare. 2021. Media, Conflict and Peacebuilding in Africa: Conceptual and Empirical Considerations, 1st ed. Edited by Jacinta Maweu and Admire Mare. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, George Herbert, and Arhtur Edward Murphy. 1932. The Philosophy of the Present. Amherst: Prometheus. Available online: https://brocku.ca/MeadProject/Mead/pubs2/philpres/Mead_1932_toc.html (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Millar, Gearoid. 2014. An Ethnographic Approach to Peacebuilding: Understanding Local Experiences in Transitional States. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mishler, Elliot G. 1986. Research Interviewing: Context and Narrative. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mishler, Elliot G. 1995. Models of Narrative Analysis: A Typology. Journal of Narrative and Life History 5: 87–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogekwu, Matt. 2011. Conflict Reporting and Peace Journalism: In Search of a New Model: Lessons from the Nigerian Niger-Delta Crisis. Sydney: Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Munslow, Alun. 1997. Deconstructing History. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ndeke Luka. 2020. RCA: Le Comité de Suivi du Forum de Bangui Insatisfaite de L’application des Recommandations. Available online: https://www.radiondekeluka.org/actualites/politique/36195-rca-le-comite-de-suivi-du-forum-de-bangui-insatisfaite-de-l-application-des-recommandations.html (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Nünning, Ansgar. 2010. Making Events—Making Stories—Making Worlds: Ways of Worldmaking from a Narratological Point of View. In Cultural Ways of Worldmaking: Media and Narratives (Vol. 1). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgeret, Kristin Skare. 2021. Insights on Peace and Conflict Reporting, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffenholz, Thania. 2015. Unpacking the Local Turn in Peacebuilding: A Critical Assessment towards an Agenda for Future Research. Third World Quarterly 36: 857–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Jeff. 2005. Chapter Three: Narrative as Knowing, Evocation, and Being. Counterpoints 248: 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- p’Lajur, John Muto-Ono. 2006. The Challenges of Reporting the Northern Uganda Armed Conflict. In Media in Situations of Conflict: Roles Challenges and Responsibility. Edited by Adolf E. Mbaine. Kampala: African Books Collective, pp. 62–86. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1995. Narrative Configuration in Qualitative Analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 8: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radio Ndeke Luka. n.d. Notre Charte—Radio Ndeke Luka. Radio Ndeke Luka. Available online: https://www.radiondekeluka.org/notre-charte.html (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Ricoeur, Paul. 1984. Time and Narrative. Vol. 1: Repr. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Clemencia. 2011. Citizens’ Media against Armed Conflict: Disrupting Violence in Colombia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Clemencia. 2015. Community Media as Performers of Peace. In Communication and Peace: Mapping an Emerging Field. Edited by Julia Hoffmann and Virgil Hawkins. Routledge Studies in Peace and Conflict Resolution. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- RONGDHRCA. n.d. Réseau des ONG des Droits de l’Homme en RCA. Available online: https://rongdhrca.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Rossman, Gretchen B., Sharon F. Rallis, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2017. An Introduction to Qualitative Research: Learning in the Field, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Susan Dente. 2006. (De)Constructing Conflict: A Focused Review of War and Peace Journalism. Conflict & Communication 5: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Fabíola Ortiz dos, and Viviane Schönbächler. 2022. Influencing Factors of ‘Local’ Conflict Journalism and Implications for Media Development: A Critical Appraisal. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 11: 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, Paddy. 1991. Broadcast Talk. London and Newbury Park: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schirch, Lisa. 2004. The Little Book of Strategic Peacebuilding. Little Books of Justice & Peacebuilding. Intercourse: Good Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker, Emrys, and Nicole Stremlau. 2014. Media and Conflict: An Assessment of the Evidence. Progress in Development Studies 14: 181–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senehi, Jessica. 2008. Building Peace: Storytelling to Transform Conflicts Constructively. In Handbook of Conflict Analysis and Resolution. Edited by Dennis J. D. Sandole, Sean Byrne, Ingrid Sandole-Staroste and Jessica Senehi. London: Routledge, pp. 201–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Ibrahim Seaga, Jake Lynch, and Robert A. Hackett, eds. 2012. Expanding Peace Journalism: Comparative and Critical Approaches. Sydney: Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shinar, Dov. 2003. The Peace Process in Cultural Conflict: The Role of the Media. Conflict & Communication 2: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shinar, Dov. 2007. Epilogue: Peace Journalism—The State of the Art. Conflict & Communication Online 6: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, Andre C., and Brett Smith. 2008. Narrative Constructionist Inquiry. In Handbook of Constructionist Research. Edited by James A. Holstein and Jaber F. Gubrium. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Suchenwirth, Lioba, and Richard Lance Keeble. 2011. Oligarchy Reloaded and Pirate Media: The State of Peace Journalism in Guatemala. In Expanding Peace Journalism: Comparative and Critical Approaches. Edited by Ibrahim Seaga Shaw, Jake Lynch and Robert A. Hackett. Sydney: Sydney University Press, p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Tayeebwa, William. 2016. Framing Peace Building. Discourses of United Nations Radio in Burundi. In Journalism in Conflict and Post-Conflict Conditions: Worldwide Perspectives. Edited by Kristin Skare Orgeret, William Tayeebwa and Elisabeth Eide. Göteborg: Nordicom, pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tomiak, Kerstin. 2018. Humanitarian Interventions and the Media: Broadcasting against Ethnic Hate. Third World Quarterly 39: 454–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN News. 2015. Ban Welcomes Central African Republic Peace Pact as Reflection of People’s Aspirations. UN News. May 11. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2015/05/498392 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- UN Panel of Experts Established Pursuant to Security Council. 2018. Letter Dated 23 July 2018 from the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic Extended Pursuant to Resolution 2399 (2018) Addressed to the President of the Security Council. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1636854 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- UNSC. 2020. Central African Republic—Report of the Secretary-General (S/2020/124). February 14. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-report-secretary-general-s2020124 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Vinograd, Cassandra. 2017. CAR: Inside an Armed Group’s ‘Peaceful’ Parallel State. October 6. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/6/inside-ndele-fprcs-peaceful-parallel-state (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Weinberg, Darin. 2008. The Philosophical Foundations of Constructionist Research. In Handbook of Constructionist Research. Edited by James A. Holstein and Jaber F. Gubrium. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, F.O.d. The Construction of Peacebuilding Narratives in ‘Media Talk’—A Methodological Discussion. Journal. Media 2023, 4, 339-363. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010023

Santos FOd. The Construction of Peacebuilding Narratives in ‘Media Talk’—A Methodological Discussion. Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(1):339-363. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Fabíola Ortiz dos. 2023. "The Construction of Peacebuilding Narratives in ‘Media Talk’—A Methodological Discussion" Journalism and Media 4, no. 1: 339-363. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010023

APA StyleSantos, F. O. d. (2023). The Construction of Peacebuilding Narratives in ‘Media Talk’—A Methodological Discussion. Journalism and Media, 4(1), 339-363. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010023