Sources, Channels and Strategies of Disinformation in the 2020 US Election: Social Networks, Traditional Media and Political Candidates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sources of Disinformation

2.2. Channels for Disinformation

2.3. Strategies of Disinformation

3. Materials and Methods

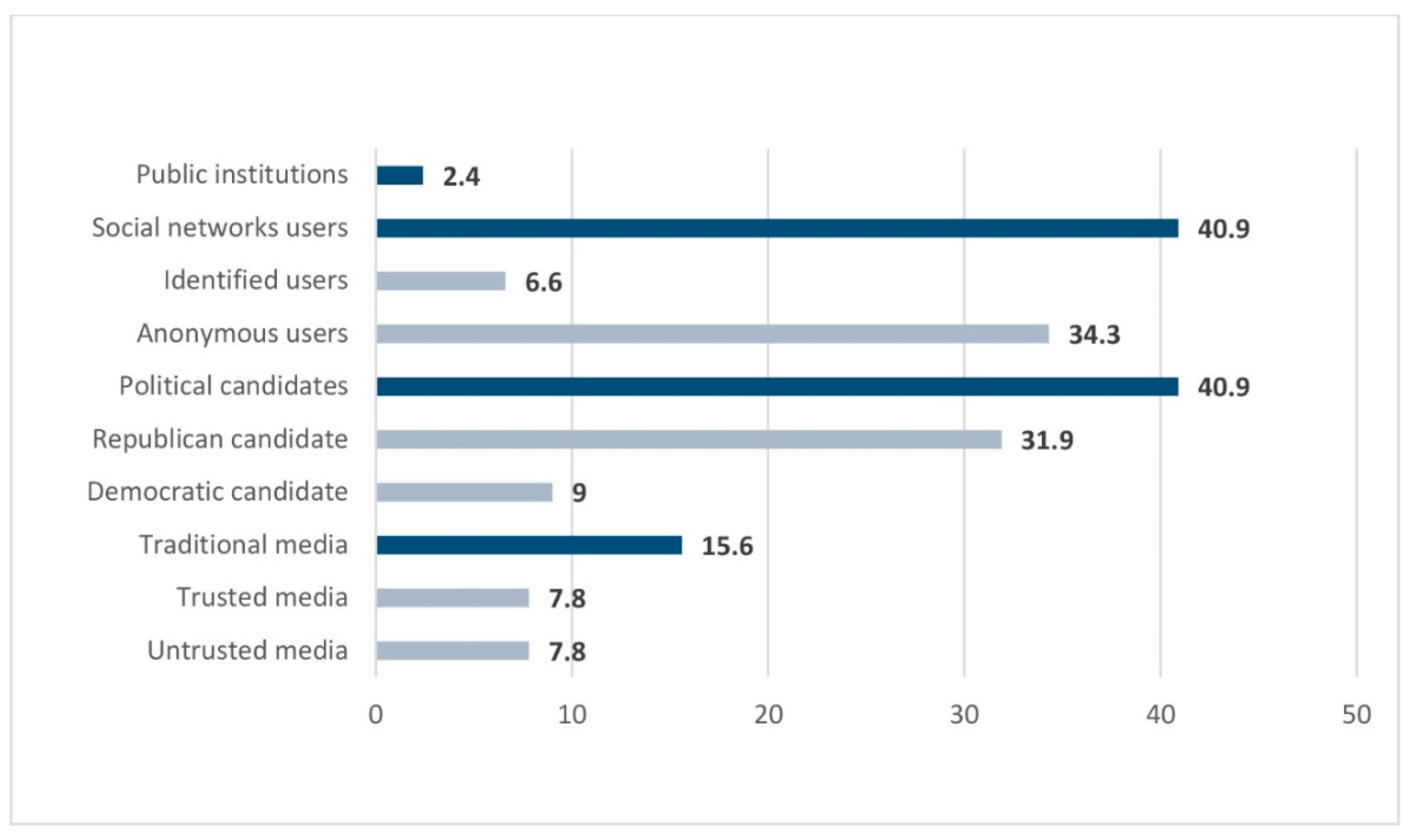

- Sources of disinformation: social networks, political candidates and traditional media;

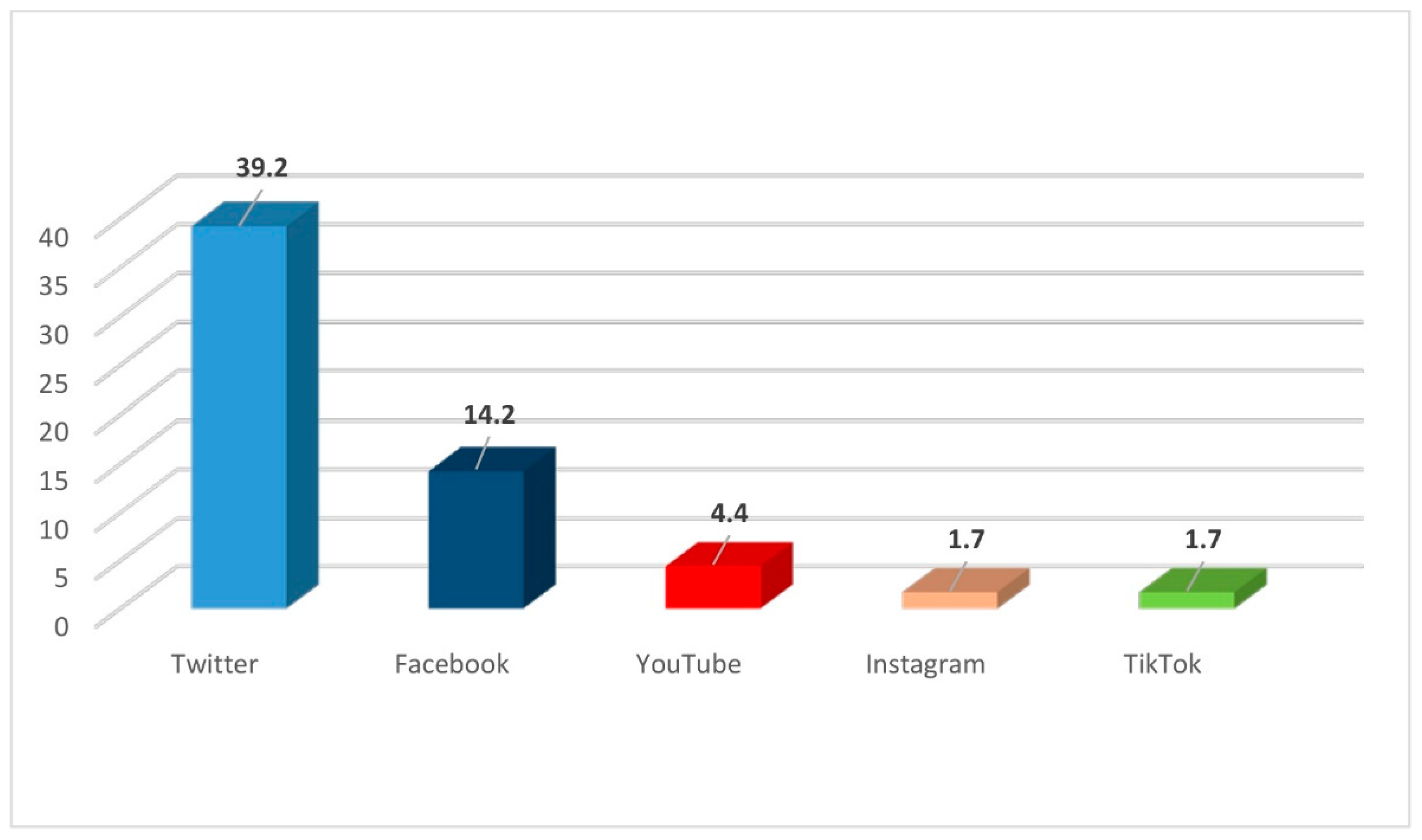

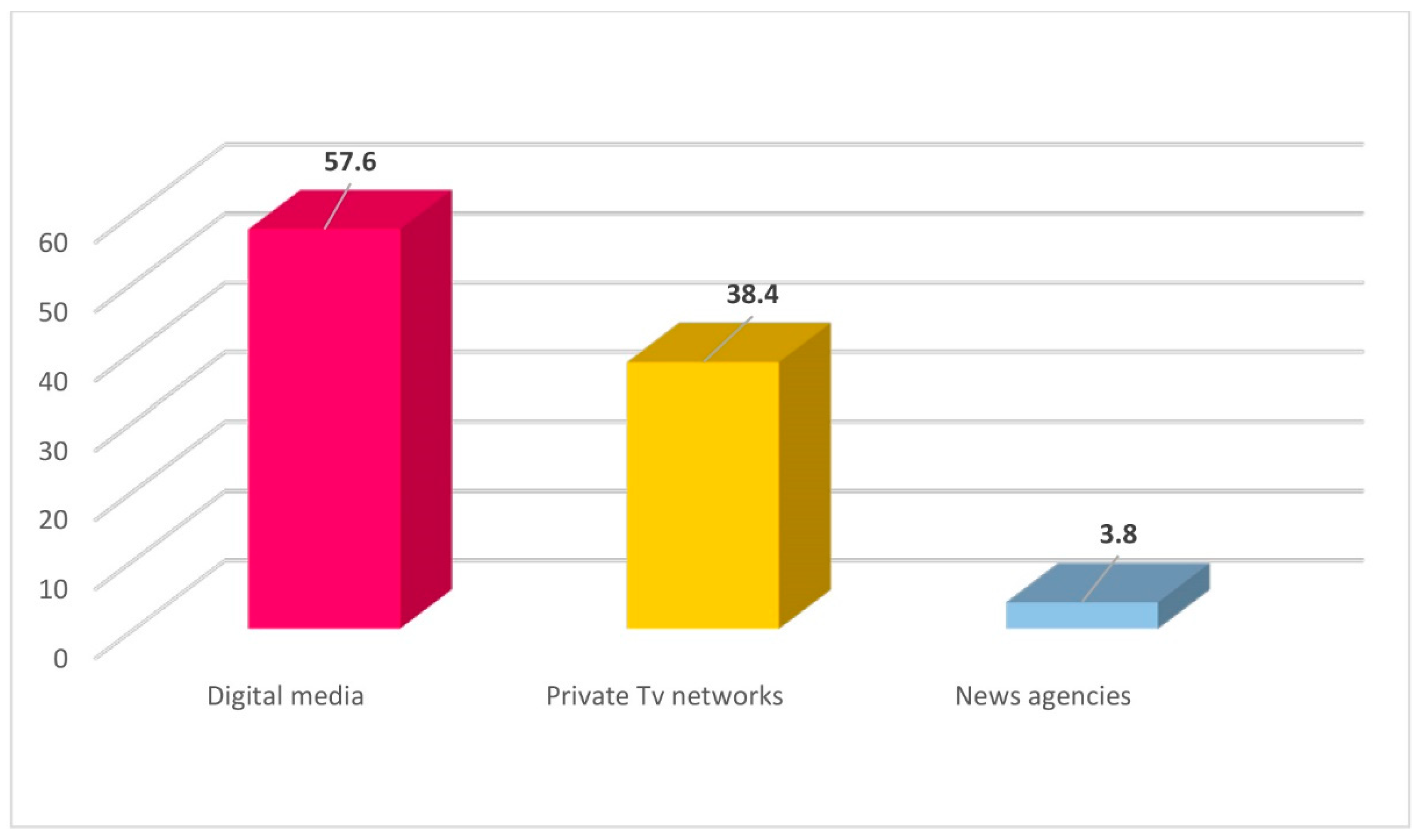

- Channels for disinformation: social networks and traditional media;

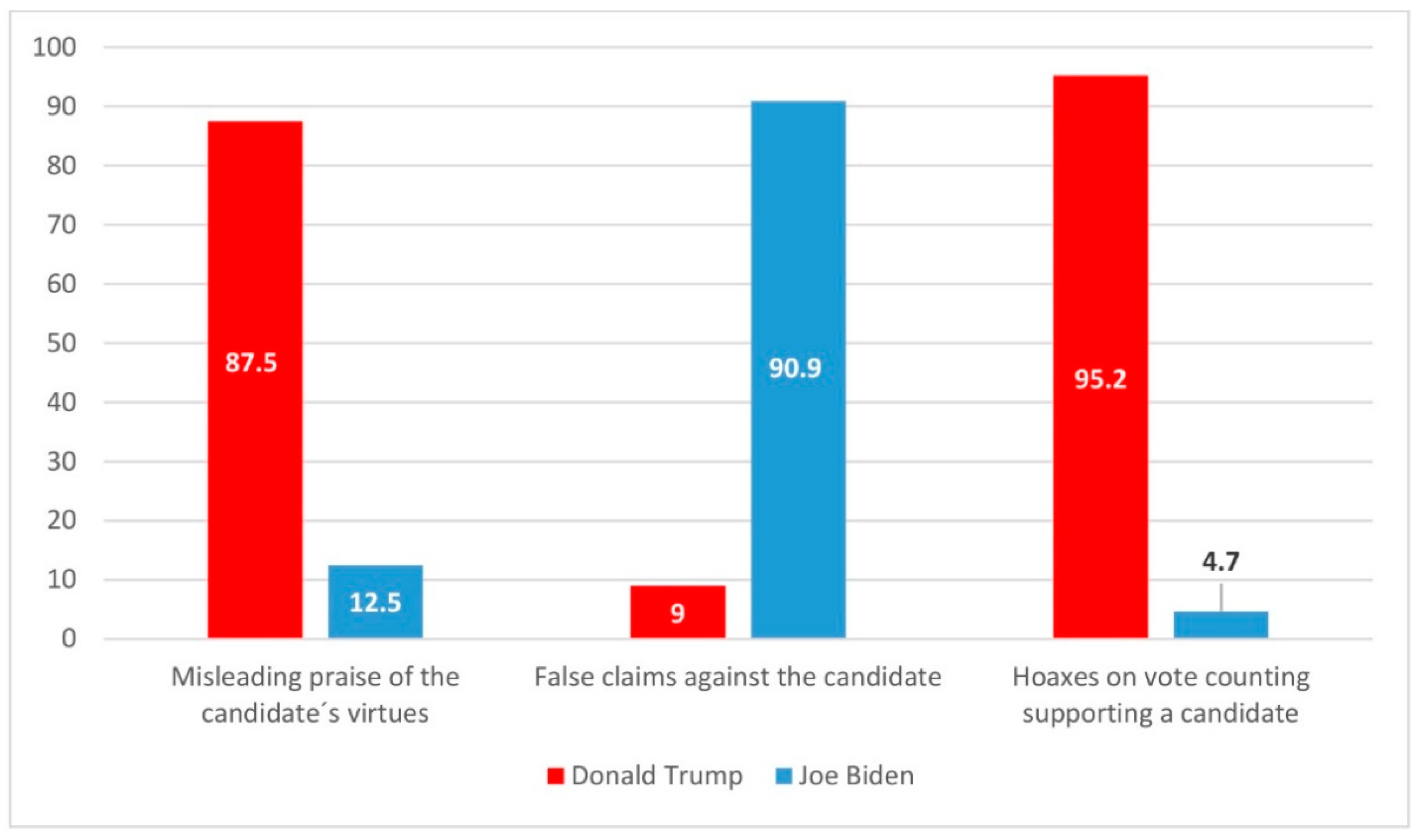

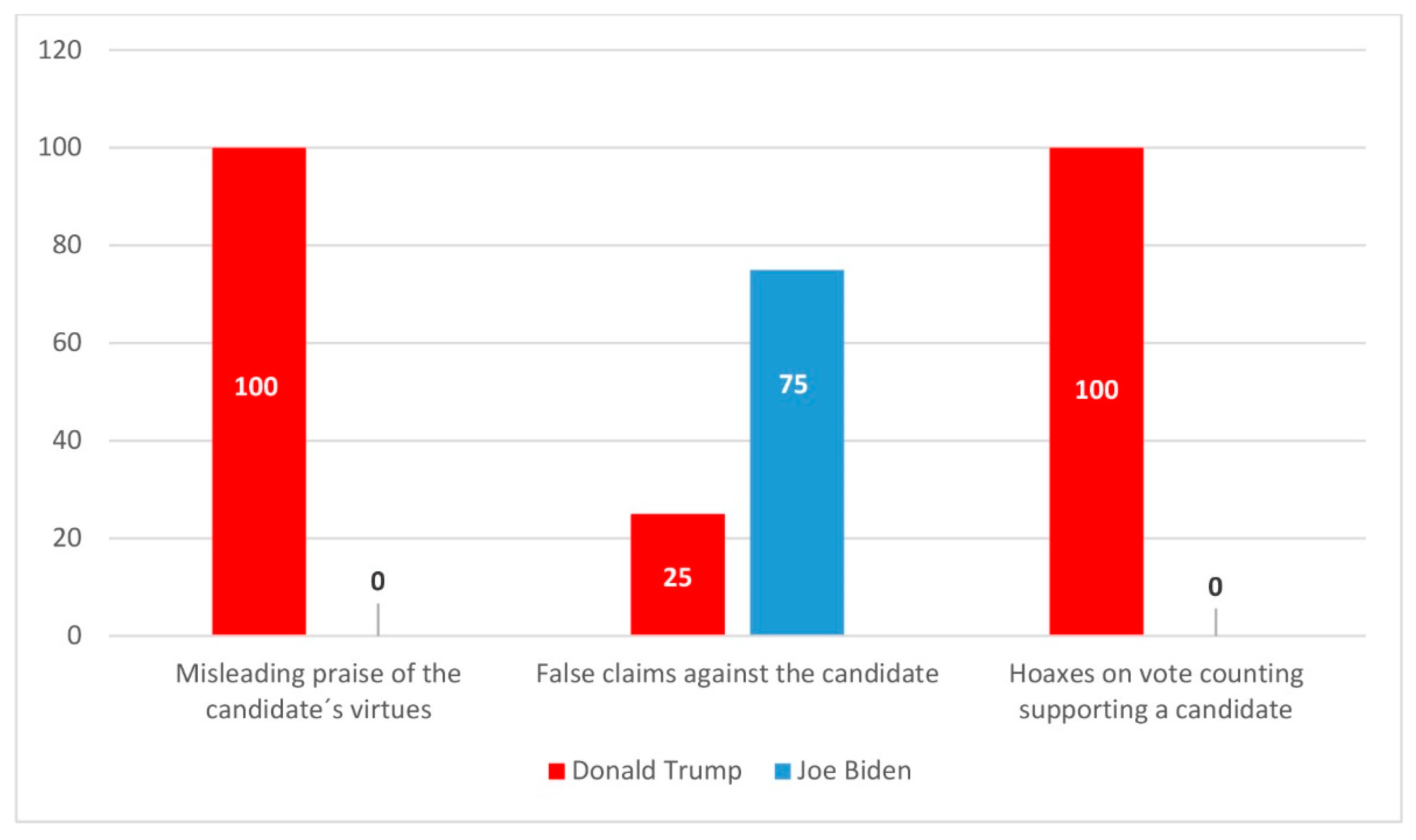

- Disinformation strategies: praise of the candidate’s virtues based on false data, false claims on the political opponent, dissemination of conspiratorial hoaxes during the electoral process.

4. Results

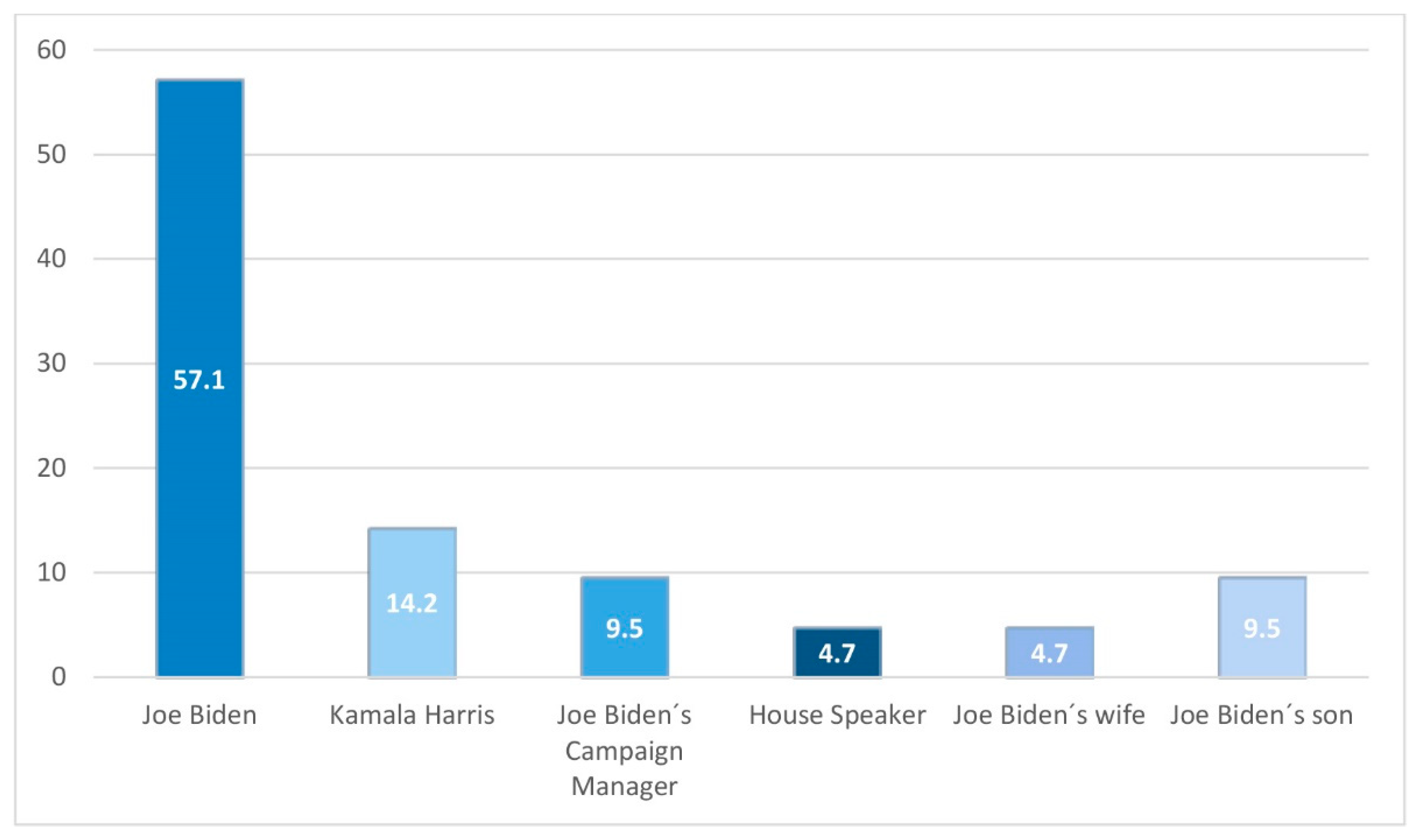

4.1. Sources of Disinformation

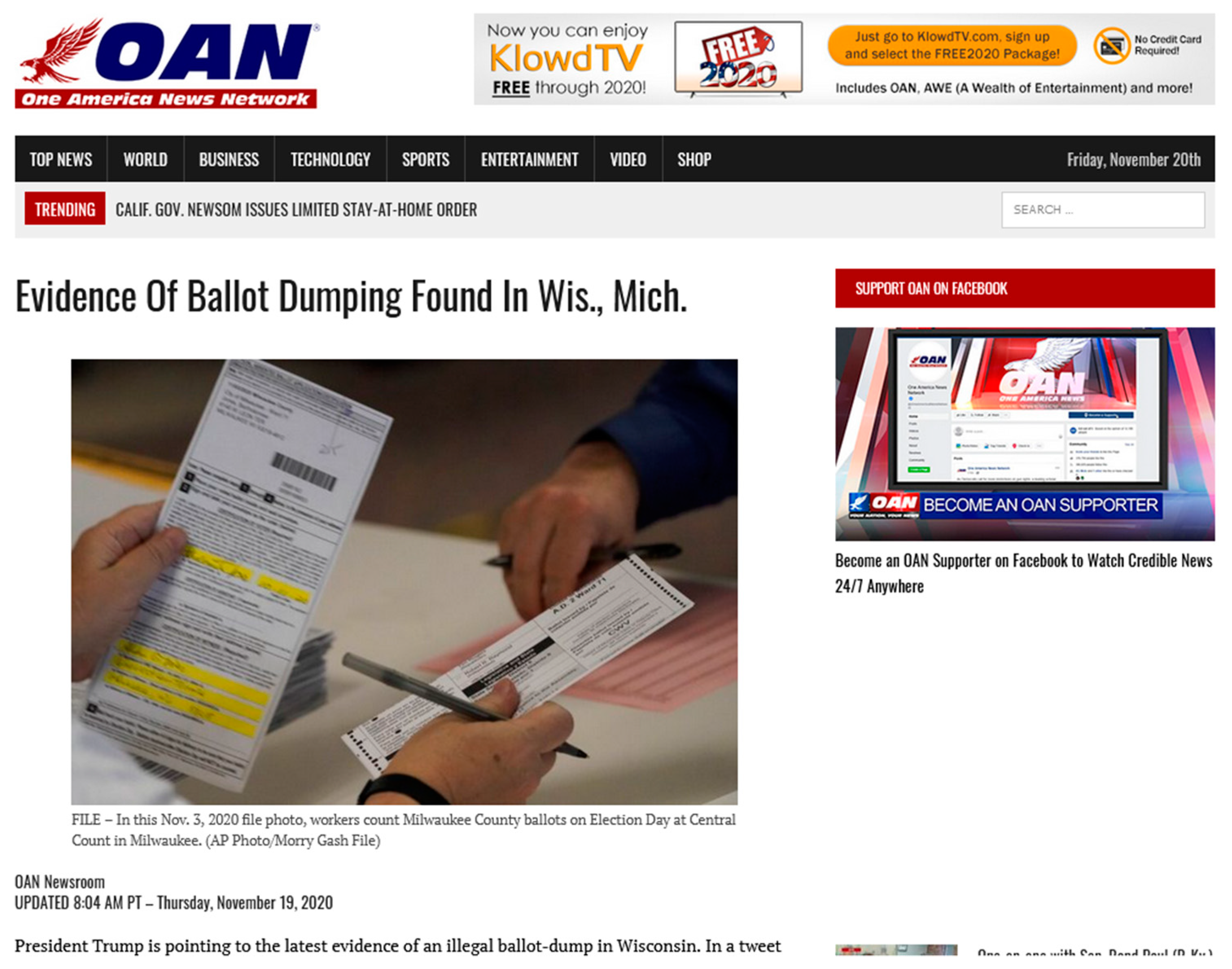

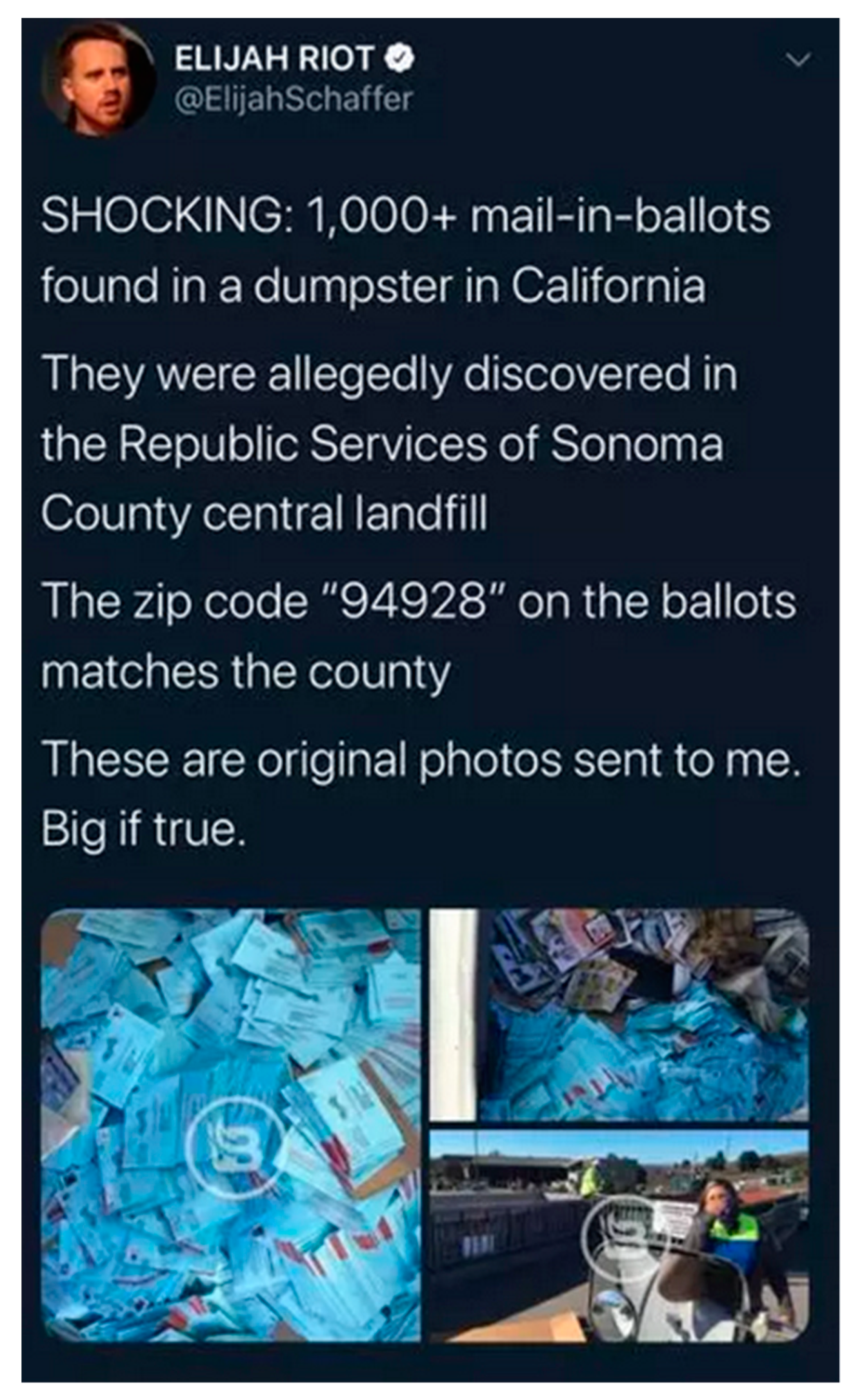

4.2. Channels for Disinformation

4.3. Strategies of Disinformation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow. 2017. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31: 211–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaissa Pedriza, Samia. 2018. Social media as news sources in Spanish digital media (“El País”, “El Mundo”, “La Vanguardia” and “ABC”). Index Comunicación 8: 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth, Lia, Aparajita Saraf, and Ceren Budak. 2020. Higher Ground? How Groundtruth Labeling Impacts Our Understanding of Fake News about the 2016 U.S. Presidential Nominees. Paper presented at International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Atlanta, GA, USA, June 8–11, vol. 14, pp. 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Caldevilla, David Domínguez. 2009. Democracia 2.0: La política se introduce en las redes sociales. Pensar la Publicidad 3: 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, Alejandro, Carlos Ballesteros, and René Jara. 2017. Social networks and electoral campaigns in Latin America. A comparative analysis of the cases of Spain, Mexico and Chile. Cuadernos Info 41: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Matt. 2020. Fake news as an informational moral panic: The symbolic deviancy of social media during the 2016 US presidential election. Information, Communication & Society 23: 374–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Andrew, and James Stanyer. 2010. Political Communication in Transition: Mediated Politics in Britain’s New Media Environment. Paper presented at Political Studies Association Annual Conference, Edinburgh, UK, March 29–April 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam, and Edward S. Herman. 1995. Los Guardianes de la Libertad: Propaganda, Desinformación y Consenso en los Medios de Comunicación de Masas. Barcelona: Grijalbo Mondadori. ISBN 84-253-2820-9. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi, Anil R., S. Raghavan, R. Weiss, and Eric Petitt. 2018. How the Supply of Fake News Affected Consumer Behavior during the 2016 US Election. Social Science Research Network (SSRN) 2020: 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Xinhuan Elham Naghizade, Damiano Spina, and Xiuzhen Zhang. 2020. Profiling Fake News Spreaders on Twitter. Paper presented at CLEF 2020 Labs and Workshops, Thessaloniki, Greece, September 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerich, N. 2015. Campaña de desinformación. In Diccionario Enciclopédico de Comunicación Política. Edited by Ismael Crespo Martínez, Orlando D’Adamo, Virginia García Beaudoux and Alberto Mora Rodríguez. Madrid: ALICE and Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales, pp. 44–47. ISSN 978-84-259-1660-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Beatriz, and Salvador Enguix. 2016. Pseudopolítica: El Discurso Político en las Redes Sociales. Valencia: Departamento del Lenguaje y Ciencias de la Comunicación, Universidad de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- García Avilés, José Alberto. 2009. La desinformación. In De Teoría de la Información y de la Comunicación. Edited by Julio César Herrero. Madrid: Universitas, pp. 327–46. ISBN 978-84-7991-252-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, Alan S., and Donald P. Green. 2000. The Effects of Canvassing, Telephone Calls, and Direct Mail on Voter Turnout: A Field Experiment. American Political Science Review 94: 653–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, Andrew, Jonathan Nagler, and Joshua Tucker. 2019. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances 5: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Lei, and Chris Vargo. 2018. “Fake News” and Emerging Online Media Ecosystem: An Integrated Intermedia Agenda-Setting Analysis of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Communication Research 45: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall Jamieson, Kathleen. 2018. Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President: What We Don’t, Can’t, and Do Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 13: 9780190058838. [Google Scholar]

- Hameleers, Michael, and Toni G. L. A. Van der Meer. 2019. Misinformation and polarization in a high-choice media environment: How effective are political fact-checkers? Communication Research 47: 227–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, Urlika, and Monika Djerf-Pierre. 2013. The Social Journalist. Embracing the social media life or creating a new digital divide? Digital Journalism 1: 368–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journell, Wayne. 2017. Fake news, alternative facts, and Trump: Teaching social studies in a post truth era. Social Studies Journal 37: 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jungherr, Andreas. 2016. Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 13: 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Haewoon, Changhyun Lee, Hosung Park, and Sue Moon. 2010. What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? Paper presented at 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, Raleigh, NC, USA, April 26–30; pp. 591–600. [Google Scholar]

- Lasorsa, Dominic L., Seth C. Lewis, and Avery E. Holton. 2012. Normalizing Twitter: Journalism Practice in an Emerging Communication Space. Journalism Studies 13: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Terry. 2019. The global rise of “fake news” and the threat to democratic elections in the USA. Public Administration and Policy 22: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleker, Darren G., Jens Tenscher, and Václav Štětka. 2015. Towards Hypermedia Campaigning? Perceptions of New Media’s Importance for Campaigning by Party Strategists in Comparative Perspective. Information, Communication & Society 18: 747–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón, Raúl. 2019. Unfaking News. Cómo combatir la desinformación. Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide. ISBN 978-84-368-4105-3. [Google Scholar]

- Magin, Melanie, Nicole Podschuweit, Jörg Haßler, and Uta Russmann. 2017. Campaigning in the Fourth Age of Political Communication. A Multi-method Study on the Use of Facebook by German and Austrian Parties in the 2013 National Election Campaigns. Information, Communication & Society 20: 1698–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, Silvia, Nadia Viounnikoff-Benet, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2020. ¿Qué hay en un like? Contenidos políticos en Facebook e Instagram en las elecciones autonómicas valencianas de 2019. Debats 134: 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, Ryan, and Whitney Phillips. 2016. Dark Magic: The memes that made Donald Trump’s victory. In US Election Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign, 1st ed. Edited by Darren Lilleker, Daniel Jackson, Einar Thorsen and Anastasia Veneti. Poole: The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community, Bournemouth University, pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-910042-11-3. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, Juan Pedro, and Raúl Magallón. 2021. Desinformación y fact-checking en las elecciones uruguayas de 2019. El caso de Verificado Uruguay. Perspectivas de la Comunicación 14: 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, Brendan, Jason Reifler, and Peter A. Ubel. 2013. The Hazards of Correcting Myths about Health Care Reform. Medical Care 51: 127–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, Diana. 2018. El papel de los nuevos medios en la política. In La Era de la Perplejidad. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, Francisco, Francisco Seoane Pérez, and Raúl Magallón. 2020. An anatomy of the electoral hoax: Political disinformation in Spain’s 2019 general election campaign. CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals 124: 123–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmelee, John H., and Shannon L. Bichard. 2011. Politics and the Twitter Revolution: How Tweets Influence the Relationship between Political Leaders and the Public. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-6500-3. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, Christina, and Thomas Koch. 2019. Countering misinformation: Strategies, challenges, and uncertainties. Studies in Communication and Media 8: 431–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Social Media Outpaces Print Newspapers in the U.S. as a News Source. Available online: https://pewrsr.ch/2UvWPSe (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Pyrhönen, Niko, and Gwenaëlle Bauvois. 2020. Conspiracies beyond Fake News. Producing Reinformation on Presidential Elections in the Transnational Hybrid Media System. Sociological Inquiry 90: 705–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Andrés, Roberto. 2018. Fundamentos del concepto de desinformación como práctica manipuladora en la comunicación política y las relaciones internacionales. Historia y Comunicación Social 23: 231–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, Patrícia, Jennifer Stromer-Galley, and Ania Korsunska. 2021. More than “Fake News”? The media as a malicious gatekeeper and a bully in the discourse of candidates in the 2020 U.S presidential election. Journal of Language and Politics 20: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Jieun, Lian Jian, Kevin Driscoll, and François Bar. 2016. Political rumoring on Twitter during the 2012 US presidential election: Rumor diffusion and correction. New Media & Society 19: 1214–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, Craig. 2016. This analysis shows how viral fake election news stories outperformed real news on Facebook. BuzzFeed. Available online: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/viral-fake-election-news-outperformed-real-news-on-facebook (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Spohr, Dominic. 2017. Fake news and ideological polarization: Filter bubbles and selective exposure on social media. Business Information Review 34: 150–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2014. Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 13: 9780199731930. [Google Scholar]

- Uscinski, Joseph, Casey Klofstad, and Matthew D. Atkinson. 2016. What Drives Conspiratorial Beliefs? The Role of Informational Cues and Predispositions. Political Research Quarterly 69: 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Dijck, José. 2009. Users like you? Theorizing agency in user-generated content. Media, Culture & Society 31: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, Peter. 2012. Twitter Links between Politicians and Journalists. Journalism Practice 6: 680–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Volkoff, Vladimir. 1986. La Désinformation, Arme de Guerre. Paris: Julliard. ISBN 10: 2260004415. [Google Scholar]

- Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. 2018. The Spread of True and False News Online. Science 359: 1146–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waisbord, Silvio. 2018. The elective affinity between post-truth communication and populist politics. Communication Research and Practice 4: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, Claire. 2018. Information Disorder. Part 3: Useful Graphics. First Draft. Available online: https://bit.ly/2wjjRAx (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Williams, Christine B., and Girish J. Gulati. 2013. Social networks in political campaigns: Facebook and the 2006 congressional elections of 2006 and 2008. New Media & Society 15: 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintersieck, Amanda. L. 2017. Debating the Truth: The Impact of Fact-Checking During Electoral Debates. American Politics Research 45: 304–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Thomas, and Ethan Porter. 2018. The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence. Political Behavior 41: 135–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Organization | Area | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | PolitiFact | Digital | Private |

| Snopes | Digital | Private | |

| Check Your Fact | Digital | Private | |

| Lead Stories | Digital | Private | |

| United Kingdom | BBC Reality Check | Broadcasting | Public |

| France | AFP Fact Check | Digital | Public |

| Les Observateurs de France 24 | Broadcasting | Private | |

| Spain | EFE Verifica | Digital | Public |

| Maldita.es | Digital | Private | |

| Newtral | Digital | Private |

| Source | Type |

|---|---|

| Traditional media | Trusted media |

| Untrusted media | |

| Public institution | The White House |

| Social media users | Identified users |

| Anonymous users | |

| Political candidates | Republican candidate and his entourage |

| Democratic candidate and his entourage |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benaissa Pedriza, S. Sources, Channels and Strategies of Disinformation in the 2020 US Election: Social Networks, Traditional Media and Political Candidates. Journal. Media 2021, 2, 605-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040036

Benaissa Pedriza S. Sources, Channels and Strategies of Disinformation in the 2020 US Election: Social Networks, Traditional Media and Political Candidates. Journalism and Media. 2021; 2(4):605-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenaissa Pedriza, Samia. 2021. "Sources, Channels and Strategies of Disinformation in the 2020 US Election: Social Networks, Traditional Media and Political Candidates" Journalism and Media 2, no. 4: 605-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040036

APA StyleBenaissa Pedriza, S. (2021). Sources, Channels and Strategies of Disinformation in the 2020 US Election: Social Networks, Traditional Media and Political Candidates. Journalism and Media, 2(4), 605-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040036