Abstract

Content recommender systems have become commonplace in all digital platforms, and they profoundly alter the media content presented to users. This also applies to news recommender systems (NRSs) used by media companies. However, as it is generally accepted that diverse news coverage is crucial to maintain democratic societies, the role of NRSs is frequently questioned. We assess the development processes of NRSs at three media companies: two private ones active in several European countries, and one public service broadcaster, using a previously established conceptual model for news diversity. Ultimately, we find that news personalization is currently still more of an idea than an actual recurrent practice, and that the application of NRSs is integrated and harmonized across countries and/or other types of new media types (e.g., streaming services) of the same company. We highlight similarities and differences in approaches, objectives and rationales between private and public companies.

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, a host of scholars have established a clear link between media and democratic societies, but also the possible negative effects of increased media market concentration on news diversity (Baker 2007; Fenton 2011; Karppinen 2008, 2013; McQuail 2013; Raeijmaekers and Maeseele 2015). Therefore, the commonly accepted viewpoint is that journalists and media companies, as the so-called ‘fourth estate’ (Van Aelst et al. 2008), have what is known as a ‘social contract’ with politicians and citizens (Sjøvaag 2019). This metaphorical contract states that journalists receive the means and opportunities to freely and critically report on events and present a diverse news offering to citizens. This allows the latter group to fulfill their democratic duties in society, of which duly voting in fair elections is the principal one. Yet, cost-cutting measures following mergers and takeovers from media ownership and brand levels are jeopardizing the diversity of news production, content and dissemination (Hendrickx and Ranaivoson 2019; Hendrickx et al. 2021).

The rise of digital platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram and their algorithmic recommender systems, have given birth to fears about what is known as filter bubbles or echo chambers (Gharahighehi and Vens 2020). To keep users within a given platform, they are offered content they like based on previous behavior, possibly without taking into account content or viewpoint diversity. Legacy media companies are currently employing similar techniques to boost news consumption and online subscription numbers and embed it in their approaches and objectives (e.g., company KPIs). Various studies, however, have found very little or no clear proof of the actual existence of filter bubbles or echo chambers, leading to an actual narrowing of content diversity for users (Dubois and Blank 2018; Haim et al. 2018; Möller et al. 2018; Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. 2016).

Notwithstanding this, lingering questions about the specific duty and role of news recommender systems (NRSs) in maintaining diverse news offerings and democratic societies remain pertinent in academia (Helberger 2019). The topic has rapidly gained traction in recent years, with an array of scholars from fields such as computer sciences, legal studies and (online) media studies discussing and proposing methods for how NRSs could or should operate, how media policy is consistently lagging behind in setting up rules for its application, and how citizens in societies desire and perceive NRSs (Bernstein et al. 2020; Bodó et al. 2019; Gharahighehi and Vens 2020; Joris et al. 2021; Van Damme et al. 2019). However, the actual process of developing and rolling out NRSs within media companies has remained largely under-researched (Bodó 2019), and the same applies to its ramifications for societies.

This article draws from a series of semi-structured expert interviews carried out in early 2021. We spoke with various employees of three leading private and public media companies originating in Flanders (Belgium), of which two are also active in various other European countries. The employees were asked for insights regarding their approaches toward and rationales behind NRSs. Hence, this article wishes to contribute to scholarship at two distinct levels. Firstly, we assess the impact of NRSs on news from a new, holistic approach; we apply a previously elaborated conceptual model on news diversity to the production and application processes of NRSs within said three corporations. Secondly, we translate the news diversity model to one of the latest innovations in news media, thereby solidifying its applicability. Additionally, we aim to fill the gap between theory and practice, as it transcends concepts and theories for NRSs by looking at actual processes of creating NRSs within three legacy media companies active in various European countries.

2. Literature Review

2.1. News Diversity and Democratic Societies

The relationship between (news) media, democracy and society has been extensively studied by a string of scholars from around the world (Baker 2007; Curran 2011; McQuail 2013; Raeijmaekers and Maeseele 2015, to name just a few). Broadly speaking, maintaining news diversity is commonly accepted as an essential prerequisite to safeguard democratic societies (Baker 2007; Papandrea 2006; Sup Park 2014). However, defining and operationalizing news diversity within media markets and directly linking it to democracy remain arduous tasks, which scholarship has discussed at length, yet never truly managed to accomplish (Karppinen 2013; Loecherbach et al. 2020; Sjøvaag 2016).

Consolidated media ownership and increasingly concentrated markets have fostered worries about the narrowing of public discourse in news titles (Baker 2007). This was already a fear expressed by American courts in the 1930s, and its negative impact on news content diversity was empirically proven for the first time in the next decade (Bigman 1948; Guardino and Snyder 2012). In Europe, neoliberal policies from the 1980s onwards signaled similar deregulation and consolidation practices, and subsequently similar concerns regarding pluralism and diversity (Meier and Trappel 2003; Raeijmaekers and Maeseele 2015). Over the years, various European scholars have established a negative relationship between increased media market concentration and the diversity of news reporting in terms of actors and sources (e.g., Beckers et al. 2017; Fenton 2011; Vogler et al. 2020). These similar findings have frequently been positioned as potentially jeopardizing the diverse information flow of citizens and their opportunities to fulfill their democratic duties in society. However, said relationship has not always been established as merely negative, with some studies finding no negative or even positive effects of media consolidation and content diversity (e.g., Sjøvaag 2014; Skärlund 2020). Furthermore, scholarship has also pointed out that ‘too much’ diversity is not always a good thing either due to possible dramatic increases of fragmentation within societies due to the lack of a shared, common agenda (Atwater 1986; Beckers et al. 2017; Calhoun 1992; Helberger 2019). Hence, while academia, (media) policy makers and practitioners in general appear to agree that diversity is important, we, too, do not venture that it is desirable in all cases, necessarily. The need for sound information from reputable sources and the rise of disinformation makes for an excellent case to prove this point, particularly in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic and its reporting throughout the world (e.g., Roozenbeek et al. 2020).

This appropriately amplifies the sheer diversity which exists in itself as a leitmotif throughout the various European media markets’ set-ups and structures.

Furthermore, they distinguish themselves from their American counterpart through the presence of (at least partly) state-funded European public service media (PSM). They were from the onset used as political instruments to foster democracy, pluralism and public debate within societies (Bardoel and d’Haenens 2008; Helberger 2019) and ‘have generated enough support and lobbying power to assure their continued existence’ (Karppinen 2013, p. 173). In spite of different characteristics and traditions per country or even region, PSM remain dominant players in most Western and Northern European media markets. According to the 2020 Digital News Report, PSM rank highest in lists of most trusted news brands in 18 out of 26 assessed European countries and regions, including Flanders (Newman et al. 2020).

In the case of commercial media, substantial audiences are required to maintain sufficient advertisement deals and financial viability, meaning that editors constantly have to weigh societal impact with economic market constraints. However, public service media, too, care about audience ratings and reach numbers, as they are a testament to their societal relevance, as they cannot be completely isolated from private market pressures (Steemers 2003). In many European cases, they are obliged to reach large parts of society to fulfill their financial and societal remit (Donders 2021) in what are basically ‘public service KPIs’. Put differently, the ephemeral struggle lies in giving citizens what they need to know (typically labelled as hard news, e.g., political news) as opposed to what they like to know and will drive up consumption and profits (soft news, e.g., celebrity news) (Gans 2009). This market-driven struggle poses a consistent threat to ensuring a well-informed citizenry. However, theory only seldomly closely corresponds with practice, and this is also the case for journalism (studies) (Strömbäck et al. 2012), meaning that the determinants as well as the demarcations of what people ‘need’ and ‘want’ to know are highly normative and blurry. We follow Tandoc and Thomas (2015; quoted in Helberger 2019, p. 1002) and their claim that ‘if journalism is to help bring about the common good, it must provide the public with more than just what the public wants’.

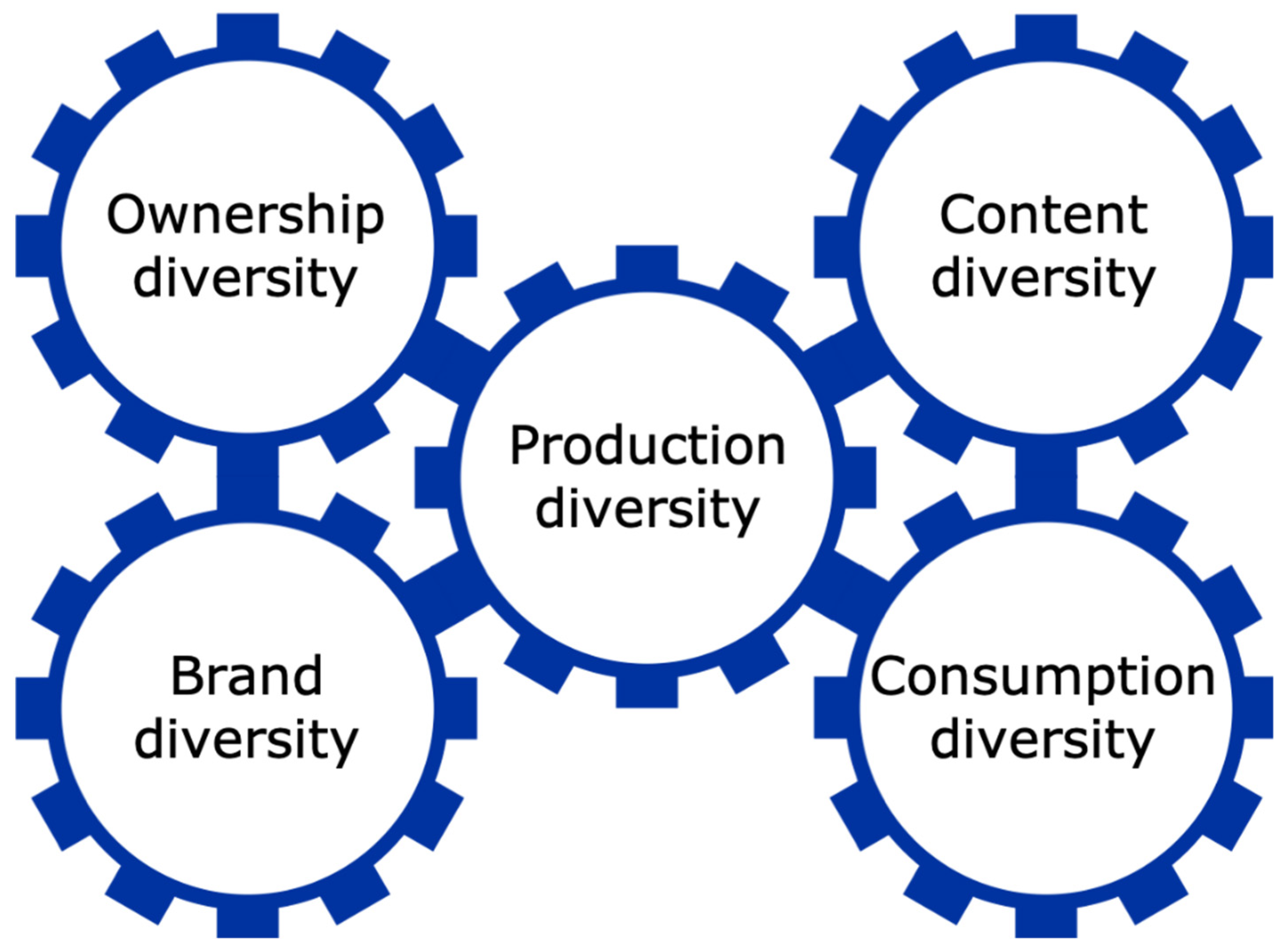

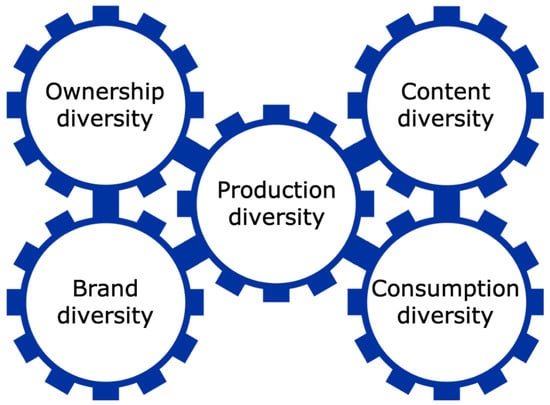

Conceptually, we study the crossroads of the diversity of news production and consumption (as received by citizens in society (McQuail 1992)) with content diversity (as sent by media companies, ibid.) also playing an important role. This stems from a holistic model of news diversity comprised of five components elaborated in a previous publication (see Figure 1 below), which are based on prior typologies of media and/or news diversity (e.g., McQuail 1992; Napoli 1999; Sjøvaag 2016). The components are presented as metaphorical ‘gears’ of a machine, said to set one another in motion and thus be interlinked and influence each other for better or for worse. Production, content and consumption diversity aside, the model also distinguishes ownership and brand diversity.

Figure 1.

Model of news diversity (Hendrickx et al. 2020).

We consider them as directly relevant for our paper and overall contribution, as they play a vital role in our assessment of the use of news recommender systems (NRSs) within three different media companies with a host of different brands scattered across platforms, target audiences and national borders. In this model, we apply the model and the effect of and relationship between its five components to NRSs, which ultimately deal with an alternative form of content dissemination to individualized target audiences based on previous reading and/or viewing behavior, as opposed to traditional, curated dissemination to mass audiences.

2.2. News Recommender Systems and Democratic Societies

Within just a few years’ time, content personalization has become effectively commonplace at nearly all digital platforms used by citizens (Gharahighehi and Vens 2020). Commercial players, such as Amazon, Facebook, Google and Netflix, were and remain the main global online players to prove the practical and financial feasibility of matching users to content they like. These practices have fueled questions, and immediate concerns, about their transferability to news platforms and content, even though the notion of a personalized news offering is already over 25 years old (Negroponte 1995). The concerns, again, predominantly deal with the possible erosion of a common public news agenda, due to increased personalized news offerings, whereas a shared list of main (news) topics is vital to preserve cohesion within societies (Beckers et al. 2017; Calhoun 1992). Thus, whereas too similar news is a threat to diversity, so is news that is too diverse; there is no threshold to establish where ‘optimal diversity’ lies (Loecherbach et al. 2020).

Recommender systems designed to personalize news content, henceforth referred to as news recommender systems (NRSs), are rapidly gaining scholarly attention (Bernstein et al. 2020; Helberger 2019). In their seminal work on news personalization mechanisms, Thurman and Schifferes (2012) distinguished explicit recommendations, in which users select favored news topics and are presented relevant content accordingly, and implicit recommendations, whereby citizens allow media companies access to their user data to construct individual digital profiles provided with personalized recommendations. The latter has been branded as ‘the second generation of news personalization’ (Bodó 2019, p. 1055), as it is increasingly becoming commonplace at media companies. As Helberger (2019) argued, the practice of altering news exposure at the level of individuals through algorithms comes with responsibilities and fundamental questions about ‘the role of news recommenders in accomplishing the media’s democratic mission’ (ibid., p. 994). She differentiated between four types of democratic news recommenders:

- Liberal recommenders in which the autonomy and rights of citizens to receive information is safeguarded (Eskens et al. 2017).

- Participatory recommenders in which citizens are actively nudged, coached and engaged to try, for instance, political news content.

- Deliberative recommenders that ‘can present the greatest opportunities to the democratic process, as well as the most profound threats’ (Helberger 2019, p. 1005), and ‘could give particular visibility to public service media content’ (ibid., p. 1006).

- Critical recommenders that ‘push readers out of the comfort zone of established opinions and engage the more marginalized voices in society’ (ibid., p. 1007). Helberger (2019) acknowledges that these are not feasible under market conditions but can be relevant as well for PSM.

NRSs distinguish themselves from recommendation systems in areas such as e-commerce or media entertainment. Conceptually, it is accepted that news content, unlike other types of media content, is not merely a product or commodity. This is fostered by its acknowledged endured political support and societal relevance and impact (Karppinen 2013; Sjøvaag 2019) and, mainly in Europe, also by strong competition of PSM without overt profit-driven motives. When looking at online news, other differences are laid bare. News content is highly dynamic and versatile, meaning that the available body of news articles to personalize and offer to users can change instantly based on current affairs (Gharahighehi and Vens 2020). The choice of which news content was offered, and where and how this was effectuated, was always a prerogative of editors-in-chief of news titles, such as newspapers or TV news broadcasts. Following the traditional gatekeeper and agenda-setting models, and their noted demise, editors of mass news media outlets used to largely determine the information flow of sizeable portions of societies (Vargo et al. 2018; Vos 2019). However, due to the previously mentioned established link between preserving news content diversity and democratic systems, this is different from other types of media content personalization, and, as such, warrants specific approaches and discussions.

When adopting the use of NRSs, the judgment of professional editors in selecting content for users and citizens is mitigated by algorithmic technologies, which are designed to increase the commercial value of news content (Diakopoulos 2019, p. 184). As such, NRSs are arguably more likely to offer citizens content that they appreciate, such as soft news. This possibly only exacerbates the above-discussed struggle between giving citizens what they ‘need’ and ‘want’. From the above understanding that both private and public news media have the objective of reaching wide audiences, we want to focus on how this translates in differences and similarities in their NRSs production and elaboration processes.

Just a few studies have looked at the attitudes and perceptions of citizens toward (automated) news selection mechanisms. A 26-country survey revealed that audiences believe algorithmic selection, based on personalized digital profiles, is a better way to obtain news than through editorial curation (Thurman et al. 2019). In their analysis of Belgian citizens’ appreciation of news selection mechanisms, Joris et al. (2021) distinguish between three different types of mechanisms: firstly, content-based similarity, which strives for similarity between news content; secondly, collaborative similarity, which strives for similarity between news users; and thirdly, content-based diversity, which aims for diversity in the news content consumed. They find that content-based similarity is most preferred. While this acknowledges the commercial mindset of media corporations providing citizens with content that they appreciate, the authors also warn of selective exposure and favoring information that reinforces pre-existing views (ibid, p. 15). This is a clear sign of demand-driven logics in news offerings, which can negatively affect the diversity of viewpoints and opinions that citizens are exposed to through the use of NRSs.

Juxtaposed to the above, scholarship has also argued for a ‘public service algorithm’. Popularized by the British scholar James Bennett, the algorithm is intended to leverage public service principles of exploration (with PSM as ‘a window on the world’) and serendipity in the digital age (Reviglio 2019), and to let citizens encounter content they otherwise would not, rather than providing similar content (Bennett 2018). Originally, the idea was propagated for video streaming services, such as the BBC iPlayer, of which similar services of other European PSM have been discussed by scholarship (Sørensen 2020; Van den Bulck and Moe 2018). Currently, it is emerging as a similar viable possibility to ensure topic and viewpoint diversity in news offered by PSM (Joris et al. 2021). This, again, stems from the normative viewpoint that PSM have additional duties and responsibilities to offer diverse opinions and voices in their reporting to fulfill their remit (Donders 2021; Helberger 2019). However, it also begs the question of to what extent the commercial logic behind algorithms (which is catered toward offering citizens relatable content that they like) and trying to persuade citizens to engage in serendipitous news consumption (which entails being confronted with viewpoints opposed to one’s own) are reconcilable. We set out to study how various media companies develop and roll out NRSs, how this ties in with different corporate key performance indicators (KPIs) and objectives, and what the effects on news diversity can be. This culminates in the following research questions:

RQ1: How do ownership and brand diversity affect production, content and consumption diversity in light of news recommender systems (NRSs)?

RQ2: Are there differences or similarities in the relationship between news diversity and NRSs among private and public service media companies?

3. Research Design

We executed a case study of three leading media companies active in Flanders (Belgium): DPG Media, Mediahuis and VRT. DPG Media and Mediahuis are two main private corporations and were both founded in the past decade after a string of mergers and takeovers. Aside from owning nearly all legacy commercial Flemish print, radio, TV and online news brands, they own and control a plethora of digital classifieds and popular and quality titles in, at the time of writing, the Netherlands, Denmark, Ireland and Luxembourg. VRT is the Flemish public service broadcaster, which boasts a leading online news brand as well as TV and radio news broadcasts for various channels and target groups.

Between March and May 2021, we carried out a total of 11 semi-structured expert interviews with employees of the three firms (an anonymized interviewee list is added as an Appendix A). All interviews lasted between 30 and 50 min in length and were recorded, transcribed and coded. This inductive approach facilitated pinpointing differences and similarities in rationales and approaches toward news recommender systems. Initially, we selected a limited number of various employees to interview, with the aim of speaking with a digital product owner, editor(-in-chief) and online journalist at each of the three assessed firms to spot hierarchical differences as well, going beyond the distinctions between corporations. However, we applied snowball sampling and asked interviewees to recommend us other persons from their organization to speak (Palinkas et al. 2015), while making sure that everyone we spoke with had a clear link with the supply side of news content (Smets et al., forthcoming). Following Rowlands et al. (2016), we stopped after the garnered data became ‘progressively redundant,’ which ‘indicates to the researcher that [a] saturation point has been reached and that further interviews [are] superfluous’ (ibid., p. 43).

As we want to bridge the gap between theory and practice when it comes to the implementation of NRSs and their impact on news diversity, we apply the previously discussed typology of news diversity to answer our main research question. Therefore, we seek to investigate the relationship between production and consumption diversity when taking into account various other relevant actors and stakeholders in implementing NRSs and, as such, their (in)direct ramifications on overall news diversity in democratic societies (Smets et al., forthcoming).

4. Results

Key findings of the interviews with employees of private companies DPG Media and Mediahuis and public service media VRT are discussed below. They are discussed in line with the two research questions of the paper at hand.

RQ1: How do ownership and brand diversity affect production, content and consumption diversity in the light of news recommender systems (NRSs)?

At private and public companies alike, we find that NRSs are developed at the level of media companies and their direct owners. Here, we denote strong standardization tendencies that aim at facilitating synergy strategies across the companies’ brands (Author). As a consequence, we find that ownership and brand diversity play a crucial role in news diversity overall and the application and rationales behind NRSs. Interviewees of the two private companies revealed that the technological knowhow behind algorithmic news recommender systems is partly produced for and in, as well as shared between, various other news brands in different countries owned by the companies:

‘We have to align different strategic objectives of different news titles. That is why websites and apps of our similar Dutch and Flemish news brands (e.g., quality and popular titles) look very similar, as the technological backend software and recommender systems are developed at the company level as opposed to the brand level. This facilitates reaching similar objectives per type of news title.’(Digital product owner, commercial media)

This notion, however, was critically questioned by one of the online journalists we spoke with, who highlighted cultural differences between regions, countries and markets:

‘An algorithm that works in the Netherlands, is not destined to work in Flanders as well, not to mention Wallonia. If there would be an algorithm for personalized news, I do wonder to what extent it is applicable to all news titles across countries. I can perfectly imagine that algorithms for similar titles wouldn’t correspond as expected, because they are operating from different countries and markets.’(Online news journalist, commercial media)

Next, we denote only a weak link between production and consumption diversity. Journalists are not systematically involved in the development or implementation or NRSs, and the ones we interviewed did not express any interest in changing this any time soon. Moreover, as of 2021, the three assessed companies are not personalizing large sections of their online news content to citizens. All three have offered them the opportunity to choose news topics of their choice to receive self-selected recommendations for several years (cf. Thurman and Schifferes 2012), though they never truly caught on. Implicit recommendations, based on digitally assembled profiles through user data (Bodó 2019), remain rare at the time of writing. Editor-led human curation remains broadly supported over algorithmic content curation. This means that content diversity itself is not yet explicitly affected by the use of NRSs:

‘It might sound a bit idealistic, but journalists should devote their time to reporting from their own expertise, without caring that much about how many people read or watch their pieces. That are worries for editors or news managers, who are best equipped to maintain the healthy balance between various topics.’(Online news journalist, commercial media)

‘We see that the broadcasting function of our brands remains vital. People visit a news website or app to instantly see what the biggest stories of the day are. This hampers far-reaching initiatives to personalize news.’(Data analyst, commercial media)

However, with algorithms increasingly determining news stories for citizens through preselected recommendations (Thurman and Schifferes 2012), albeit still only to very limited extents, there is arguably even less of a clear relationship between the newsrooms producing news content and personalized news consumption. Hence, we identify intermediaries, such as digital product owners and data analysts, as bridge builders between these newsrooms and consumers. In any modern media company, they are firmly embedded in the daily structures and workflow, and they pose potential threats to editorial independence in the light of noted standardization at the company level.

RQ2: Are there differences or similarities in the relationship between news diversity and NRSs among private and public service media companies?

All three companies have clear objectives, goals and KPIs regarding the further development of NRSs. While these were not disclosed to the authors explicitly, we find that the line between recommending news and other types of media content is fading. At the time of our interview series, DPG Media announced that it would harmonize its user account logins for all citizens, using a website or app of any of its Flemish news brands, radio channels or TV streaming service. At VRT, the ambition is to implement the recommender system on multiple platforms. For example, the algorithm behind the so-called ‘Mijn.NWS’ (My.NWS in Dutch) function within the VRT NWS mobile app, explained below, is also used for VRT’s streaming service app. Today, users are already logging in with the same credentials to use both apps. This finding is in line with the study of Bodó (2019), which already showed that technologies used to personalize online news content are simultaneously used to do the same for online advertisements and other parts of media companies.

‘Our goal is to implement recommender systems cross-brand. If someone watches a documentary about global warming at our streaming service, that person will see recommendations for recent news articles about the topic as well. We call that the public service algorithm.’(Digital product owner, public service media)

It is noteworthy that the term ‘public service algorithm’ (Bennett 2018; Joris et al. 2021) was used by our interviewee, although the interviewers did not bring it up during the conversation. This means that the moniker is, at least at VRT, firmly embedded in the rationale behind designing, developing and implementing news recommender systems.

In early 2021, VRT launched ‘Mijn.NWS’, a personalized feed within the mobile phone app of VRT’s news brand that features articles based on users’ explicitly stated preferences. The two private companies, DPG Media and Mediahuis, offer a similar form of explicit personalization for online paid subscribers and are further along in their experiments with implicit personalization. For instance, the main news title of DPG Media has firmly integrated its classifieds or verticals under its main brand. Each has its own designated home page at the website and app of HLN. They feature branded content, and their content is more prone to being personalized based on users’ behavior (Serazio 2020). Private and public media companies alike are both aware and wary of their duty to bring diverse news reporting to society and possible threats for filter bubbles and echo chambers. They are not seen as a major issue though (Bodó 2019, p. 1068), and interviewees claimed to formally distinguish between news brands and classifieds:

‘We’re not Netflix. News content is more sensitive because of editorial independence. In widening news brands through verticals, it is easier to forego this independence as they are not directly linked to news content. We don’t fill our homepages yet with personalization, as we consider that as a giant leap forward which needs more discussions with editors-in-chiefs and directors.’(Digital brand manager, commercial media)

VRT, like several other European PSM, is obliged to reach large sections of the society it presents content to, albeit differentiated per gender, age or ethnic background. VRT NWS, the news department of the Flemish PSM, provides daily televised newscasts at the main TV channel, as well as hourly radio broadcasts at five differentiated channels and news for children and teenagers via TV and social media. As opposed to news personalization, targeted at individuals, public broadcasters frequently (have to) engage in what we refer to as news segmentation, for specific parts or segments of society. The same term is sparsely used in academia to denote the division of broadcast news in topic-based segments or pieces (Christensen et al. 2005; Maybury 1998), yet we use the term segmentation from a more societal perspective, as does VRT itself, to fulfill its remit:

‘Reaching wide portions of society is very important to PSM. We find that people are very interested in news, but that it is often not available tailor-made for them and their needs. Segmentation has been a recurring practice for decades, in which we ‘translate’ radio news to the audiences of our various radio channels. They use different, relatable approaches, yet the biggest news stories themselves remain the same everywhere.’(Editor-in-chief, public service media)

Thus, whereas both segmentation and personalization are applied by media companies to diversify their offering, there are notable differences. In segmentation, news content is repackaged and ‘translated’ to diverse target audiences. With personalization through NRSs, the same body of news content is available but is deliberately shown to different people based on their interests and behavior. In terms of our conceptual model of news diversity, this translates in a difference in the role of those who produce news (i.e., the newsroom). Whereas they currently only have a rather passive stake in the deployment of NRSs, they do play an active role in segmentation practices. We find that VRT still uses segmentation more than personalization, also through its digital platforms.

‘When you are logged in at our app, we know who and where our users are. We can then send them, for instance, segmented newsletters or push notifications to their devices, based on the region they live in.’(Editor-in-chief, public service media)

However, in spite of personalization and segmentation, we find that VRT uses somewhat similar tactics and technologies to reach wider audiences as those of their private competitors. This has been a recurring practice at PSM, either because of political and/or financial pressures, or because they choose to voluntarily, as previously noted by Steemers (2003). According to Karppinen (2013, p. 170), this is ‘compatible with the broader shift where all media, including PSM, are increasingly seen as serving consumer needs, instead of the earlier rationales that saw PSM as a universal public utility or as a tool for active citizenship’. Roughly speaking, the use of commercially driven algorithms to increase consumption makes it unclear whether or not PSM perceive citizens as such, or rather as consumers. This is not a semantical question but one that could greatly impact the recommendation logics in which news users are served the news they need to instead of want to know.

In conclusion, we only denote limited differences in the relationship between news diversity and NRSs among the three assessed private and public service media companies. Predominantly, the focus on content segmentation and the so-called public service algorithm, which can foster serendipitous news consumption experiences, rather than overt personalization to offer citizens what they want to know, ties in with the remit of VRT as a PSM. However, we mainly find similarities due to the acknowledged commercial outlook in considering NRSs, and by extent news, as products and commodities at private and public media companies alike. To refer back to the notion that news is not another product or commodity and, thus, the same goes for news recommender systems, we briefly discuss the possible effects of NRSs on news diversity from the perspective of consumption diversity and society. Because of the limited degree of actual news personalization currently in use, we do not perceive any negative (in)direct outcomes of the use of NRSs on maintaining a well-informed citizenry and society as a whole. However, whereas the need for human curation is consistently emphasized, we still denote a potential slippery slope in editorial independence for editors and newsrooms in setting the news agenda, as (automated) intermediaries, such as algorithms and data analysts, are set to be foregrounded as new types of metaphorical gatekeepers (Vos 2019). Yet, the broadcasting function of private news media catering to mass audiences and the successful use of content segmentation for various target groups at PSM both signify endured relevance for both human news curation and a shared public agenda, which is a requirement to maintain cohesive societies (Beckers et al. 2017; Calhoun 1992).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

We deployed a case study of expert interviews with employees of three Flemish (Belgian) media companies to assess the effects of developing and using news recommender systems (NRSs) on overall news diversity, from five different metaphorical ‘gears’, or perspectives: ownership, brand, production, content and consumption diversity (Hendrickx et al. 2020). We found that the first two ‘gears’ highly influence the latter three, due to the centralization and standardization of processes at the corporate level and corporate or business logics seeping into parts of the news process. Throughout our interviews, it became apparent that both private and public media companies are aware and wary of their duty to bring diverse news reporting to society and possible threats for filter bubbles and echo chambers.

Based on these findings, we found that, from a conceptual perspective, with the implementation of NRSs, the focus in the news diversity model shifts increasingly to the left side, comprised of ownership and brand diversity. They predominantly affect production and consumption diversity in a myriad of ways, even though we only found a weak relationship between them in the case of NRSs. Content diversity is not (yet) directly affected, as the actual degree of personalized news content is still very low at the time of writing, with private companies mainly focusing on branded content through their classified brands (Serazio 2020). Thus, at the time of writing, human curation remains vital everywhere, as experiments with implicit personalization (Thurman and Schifferes 2012) are still in their infancy.

Our conclusions echo a number of valid points and concerns raised in previous relevant scholarship, which also applied our method of qualitatively interviewing media practitioners to gauge their attitudes regarding news personalization. For instance, we agree with all three key findings of Bodó (2019, pp. 1070–71), who found that personalization is ‘deeply embedded in the wider economic, social, political and technological contexts of news production and distribution’, that it is not ‘a monolithic technology/idea/approach’ and that ‘the autonomy of the algorithm’ is limited, precisely by human-led curation and the availability of user metrics within contemporary newsrooms. Furthermore, we are in unison with Bastian et al. (2021, pp. 854–55), who hold the view that algorithmic news recommenders are perceived as extensions of existing editorial activities occurring within newsrooms. As a result of this, the implementation of such recommenders ought to follow normative journalistic values, such as transparency, autonomy and diversity—in which the latter term is again confirmed as a key concept in both conceptualizing and operationalizing the use of algorithmic curated news content.

A prime question for the coming years, then, is how NRSs will be further developed and engrained in the targets of specific news brands and media companies as a whole. We denote a clear frontier between two and three of the five dimensions of news diversity (ownership and brand versus production, content and consumption) and expect this to be reinforced as the production and consumption of (news) media content continue to be dramatically altered. Should this imbalance between dimensions of news diversity be restored? Is it desirable that corporate levels are threatening to impact the production, dissemination and production of news content in such a significant way, while newsrooms are kept at bay? Content personalization is here to stay, and the same goes for news content—increasingly also through large, dominant social media platforms and their own intricate, opaque algorithmic selection methods on which legacy news publishers depend to generate online traffic. Thus, the importance of human-led content curation by skilled news editors continues to receive broad support as well. As a means to attempt to partly restore the balance in our news diversity model and reintegrate newsrooms more explicitly in the NRSs process, we proposed considering what we label as ‘hybrid curation’, in which either an editor chooses a number of articles to personalize, and an algorithm selects the ‘best’ one(s), or exactly vice versa, in which the algorithm automatically generates a shortlist out of which the editor can choose to the behest of her/his/their knowledge. Either method will require rigorous testing and discussing between various parties, but at least it retains the importance of editors and newsrooms in all aspects of the news process, rather than allocating all power to corporate-driven algorithms.

To further contribute to scholarship, we differentiated between private and public media companies and their divergent aims and objectives in personalizing news content for users. We found that the two private companies were unsurprisingly developing and implementing their NRSs in line with the overall company objectives and thus complying with profit-driven motives. In this sense, it was noted that the NRSs could predominantly offer their users what they want rather than what they need. However, given the small-scale deployment of their NRSs, this did not pose a significant problem, and we found both companies actively looking for solutions to maintain this contentious balance. VRT, Flanders’ public service media, was found to focus more on content segmentation rather than personalization. Both private and public media organizations (plan to) use their recommender systems for other types of content (i.e., video, classifieds) and their impact, therefore, transcends merely news diversity and extends the scope to other types of media diversity. We expect these lines to continue to blur in the coming years and invite scholars to continue to assess this in the future. Finally, we denote how VRT is increasingly taking on a rather commercial outlook as well in developing NRSs, and that this is in line with scholarship (Karppinen 2013; Steemers 2003). We hold the view that news segmentation is an overlooked feature in scholarship and invite fellow peers to study the discrepancy with news personalization more in depth, particularly, but not solely, from a news recommender system and/or public service media perspective. In our applied conceptual model of news diversity, we find that the role of production diversity is significantly different in both cases. Whereas production plays an active role in the activity of news segmentation, they currently mainly hold a passive one in news personalization. This affects what constitutes content diversity, which highly depends on the vantage point of the researcher, but also that of the journalist and editor, product manager and, ultimately, the citizen as the news user.

We venture that our results are, to high extents, transferable to other, similar Western media markets. While not (yet) of the same magnitude of European conglomerates, such as Axel Springer or Schibsted, DPG Media and Mediahuis nonetheless own various legacy news brands in different countries and are continuing to expand their European ownership. We also found that the development of NRSs is harmonized across countries, which confirms far-reaching synergy operations at the level of technology and in-house research and strengthens our point that a case study of just one small media market can be adapted to others. We also invite scholars to continue to assess the use of NRSs within both private and public media companies from a news diversity perspective, as, with this paper, we have shown how the presented model holds and is able to properly capture this new transition in media and news landscapes around the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and A.S.; methodology, J.H.; software, A.S.; validation, J.H., A.S.. and P.B.; formal analysis, J.H.; investigation, J.H. and A.S.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S. and P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and P.B.; visualization, J.H.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Anonymized list of interviewees, type of media and function.

Table A1.

Anonymized list of interviewees, type of media and function.

| # | Media | Function Title (Anonymized) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Commercial | Online Journalist |

| 2 | Commercial | Online Journalist |

| 3 | Public service | Online Journalist |

| 4 | Commercial | Digital Product Owner |

| 5 | Commercial | Digital Product Owner |

| 6 | Public service | Digital Product Owner |

| 7 | Commercial | Editor-in-Chief |

| 8 | Public service | Editor-in-Chief |

| 9 | Commercial | Data Analyst |

| 10 | Commercial | Technologist |

| 11 | Commercial | Technology Provider |

References

- Atwater, Tony. 1986. Consonance in local television news. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 30: 467–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. Edwin. 2007. Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bardoel, Jan, and Leen d’Haenens. 2008. Reinventing public service broadcasting in Europe: Prospects, promises and problems. Media, Culture & Society 30: 337–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, Mariella, Natali Helberger, and Mykola Makhortykh. 2021. Safeguarding the Journalistic DNA: Attitudes towards the Role of Professional Values in Algorithmic News Recommender Designs. Digital Journalism 9: 835–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckers, Kathleen, Andrea Masini, Julie Sevenans, Miriam van der Burg, Julie De Smedt, Hilde Van den Bulck, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2017. Are newspapers’ news stories becoming more alike? Media content diversity in Belgium, 1983–2013. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 20: 1665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, James. 2018. Public Service Algorithms. In A Future for Public Service Television. Edited by Des Freedman and Vana Goblot. Boston: The MIT Press, pp. 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Abraham, Claes de Vreese, Natali Helberger, Wolfgang Schulz, Katharina Zweig, Christian Baden, Michael A. Beam, Marc P. Hauer, Lucien Heitz, Pascal Jürgens, and et al. 2020. Diversity in News Recommendations. arXiv arXiv:2005.09495. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.09495 (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Bigman, Stanley K. 1948. Rivals in Conformity: A Study of Two Competing Dailies. Journalism Bulletin 25: 127–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodó, Balász. 2019. Selling News to Audiences—A Qualitative Inquiry into the Emerging Logics of Algorithmic News Personalization in European Quality News Media. Digital Journalism 7: 1054–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bodó, Balász, Natali Helberger, Sarah Eskens, and Judith Möller. 2019. Interested in Diversity. Digital Journalism 7: 206–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, Craig J., ed. 1992. Habermas and the Public Sphere. Boston: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Heidi, Bulut Kolluru, Yoshihiko Gotoh, and Steve Renals. 2005. Maximum entropy segmentation of broadcast news. Paper presented at the (ICASSP ’05) IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Philadelphia, PA, USA, March 23; vol. 1, pp. I/1029–I/1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curran, James. 2011. Media and Democracy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media. Boston: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donders, Karen. 2021. Public Service Media and the Law: Theory and Practice in Europe, 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, Elizabeth, and Grant Blank. 2018. The echo chamber is overstated: The moderating effect of political interest and diverse media. Information, Communication & Society 21: 729–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eskens, Sarah, Natali Helberger, and Judith Moeller. 2017. Challenged by news personalisation: Five perspectives on the right to receive information. Journal of Media Law 9: 259–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fenton, Natalie, ed. 2011. New Media, Old News: Journalism and Democracy in the Digital Age (Repr). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, Herbert J. 2009. Can Popularization Help the News Media? In The Changing Faces of Journalism. Edited by Barbie Zelizer. New York: Routledge, pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gharahighehi, Alireza, and Celine Vens. 2020. Making Session-based News Recommenders Diversity-aware. Paper presented at the OHARS’20: Workshop on Online Misinformation- and Harm-Aware Recommender Systems, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, September 25; Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2758/OHARS-paper5.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Guardino, Matt, and Dean Snyder. 2012. The Tea Party and the Crisis of Neoliberalism: Mainstreaming New Right Populism in the Corporate News Media. New Political Science 34: 527–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haim, Mario, Andreas Graefe, and Hans-Bernd Brosius. 2018. Burst of the Filter Bubble? Effects of personalization on the diversity of Google News. Digital Journalism 6: 330–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helberger, Natali. 2019. On the Democratic Role of News Recommenders. Digital Journalism 7: 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hendrickx, Jonathan, Heritiana Ranaivoson, and Pieter Ballon. 2020. Dissecting news diversity: An integrated conceptual framework. Journalism, 1464884920966881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, Jonathan, Zara Chokor, and Heritiana Ranaivoson. 2021. Meer van hetzelfde? Content sharing bij Vlaamse DPG Media-kranten. Tijdschrift Voor Communicatiewetenschap 49: 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, Jonathan, and Heritiana Ranaivoson. 2019. Why and how higher media concentration equals lower news diversity—The Mediahuis case. Journalism, 1464884919894138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joris, Glenn, Frederik De Grove, Kristin Van Damme, and Lieven De Marez. 2021. Appreciating News Algorithms: Examining Audiences’ Perceptions to Different News Selection Mechanisms. Digital Journalism 9: 589–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, Kari. 2008. Media and the paradoxes of pluralism. In The Media and Social Theory. Edited by David Hesmondhalgh and Jason Toynbee. New York: Routledge, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, Kari. 2013. Rethinking Media Pluralism, 1st ed. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loecherbach, Felicia, Judith Moeller, Damian Trilling, and Wouter van Atteveldt. 2020. The Unified Framework of Media Diversity: A Systematic Literature Review. Digital Journalism 8: 605–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maybury, Mark T. 1998. Discourse Cues for Broadcast News Segmentation. COLING 1998 Volume 2: The 17th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. COLING 1998. Available online: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/C98-2130 (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- McQuail, Denis. 1992. Media Performance: Mass Communication and the Public Interest. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, Denis. 2013. Journalism & Society. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, Werner A., and Josef Trappel. 2003. Media Concentration and the Public Interest. In Media Policy: Convergence, Concentration and Commerce. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, Judith, Damian Trilling, Natali Helberger, and Bram van Es. 2018. Do not blame it on the algorithm: An empirical assessment of multiple recommender systems and their impact on content diversity. Information, Communication & Society 21: 959–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Napoli, Philip M. 1999. Deconstructing the Diversity Principle. Journal of Communication 49: 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroponte, Nicolas. 1995. Being Digital, 1st ed. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andi, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Oxford: University of Oxford, Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Palinkas, Lawrence, Sarah M. Horwitz, Carla A. Green, Jennifer P. Wisdom, Naihua Duan, and Kimberly Hoagwood. 2015. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42: 533–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papandrea, Franco. 2006. Media Diversity and Cross-Media Regulation. Prometheus 24: 301–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeijmaekers, Daniell, and Pieter Maeseele. 2015. Media, pluralism and democracy: What’s in a name? Media, Culture & Society 37: 1042–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reviglio, Urbano. 2019. Serendipity as an emerging design principle of the infosphere: Challenges and opportunities. Ethics and Information Technology 21: 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, Jon, Claudia R. Schneider, Sarah Dryhurst, John Kerr, Alexandra L. J. Freeman, Gabriel Recchia, Anne Marthe van der Bles, and Sander van der Linden. 2020. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. Royal Society Open Science 7: 201199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, Terry, Nal Waddell, and Bernard McKenna. 2016. Are We There Yet? A Technique to Determine Theoretical Saturation. Journal of Computer Information Systems 56: 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serazio, Micheal. 2020. Making (Branded) News: The Corporate Co-optation of Online Journalism Production. Journalism Practice 14: 679–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjøvaag, Helle. 2014. Homogenisation or Differentiation? The effects of consolidation in the regional newspaper market. Journalism Studies 15: 511–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjøvaag, Helle. 2016. Media diversity and the global superplayers: Operationalising pluralism for a digital media market. Journal of Media Business Studies 13: 170–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjøvaag, Helle. 2019. Journalism between the State and the Market. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Skärlund, Sanna. 2020. The Recycling of News in Swedish Newspapers: Reused quotations and reports in articles about the crisis in the Swedish Academy in 2018. Nordicom Review 41: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smets, Annelien, Jonathan Hendrickx, and Pieter Ballon. forthcoming. We’re in This Together: A Multi-Stakeholder Approach for News Recommenders. In review.

- Sørensen, Jannick Kirk. 2020. The datafication of Public Service Media: Dreams, Dilemmas and Practical Problems a Case Study of the Implementation of Personalized Recommendations at the Danish Public Service Media ‘DR’. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research 36: 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steemers, Jeanette. 2003. Public Service Broadcasting Is Not Dead Yet. Straetegies in the 21st Century. In Broadcasting & Convergence: New Articulations of the Public Service Remit: RIPE@2003. Edited by Gregory Ferrell Lowe and Taisto Hujanen. Gothenburg: Nordicom, University of Gothenburg, pp. 123–36. Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-10005 (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Strömbäck, Jesper, Michael Karlsson, and David Nicolas Hopmann. 2012. Determinants of News Content. Journalism Studies 13: 718–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sup Park, Chang. 2014. Media cross-ownership and threat to diversity: A discourse analysis of news coverage on the permission for cross-ownership between broadcasters and newspapers in South Korea. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 10: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson C., and Ryan J. Thomas. 2015. The Ethics of Web Analytics. Digital Journalism 3: 243–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurman, Neil, and Steve Schifferes. 2012. The Future of Personalisation at News Websites: Lessons from a Longitudinal Study. Journalism Studies 13: 775–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurman, Neil, Judith Moeller, Natali Helberger, and Damian Trilling. 2019. My Friends, Editors, Algorithms, and I. Digital Journalism 7: 447–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Aelst, Peter, Kees Brants, Philip Van Praag, Claes De Vreese, Michiel Nuytemans, and Arjen Van Dalen. 2008. THE FOURTH ESTATE AS SUPERPOWER?: An empirical study of perceptions of media power in Belgium and the Netherlands. Journalism Studies 9: 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, Kristin, Marijn Martens, Sarah Van Leuven, Mariek Vanden Abeele, and Lieven De Marez. 2019. Mapping the Mobile DNA of News. Understanding Incidental and Serendipitous Mobile News Consumption. Digital Journalism 8: 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bulck, Hilde, and Hallvard Moe. 2018. Public service media, universality and personalisation through algorithms: Mapping strategies and exploring dilemmas. Media, Culture & Society 40: 875–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargo, Chris J., Lei Guo, and Michelle A. Amazeen. 2018. The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014 to 2016. New Media & Society 20: 2028–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vogler, Daniel, Linards Udris, and Mark Eisenegger. 2020. Measuring Media Content Concentration at a Large Scale Using Automated Text Comparisons. Journalism Studies 21: 1459–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, Tim P. 2019. Journalists as Gatekeepers. In The Handbook of Journalism Studies. Edited by Karin-Wahl Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch. New York: Routledge, pp. 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, Frederik J., Damian Trilling, Judith Möller, Balázs Bodó, Claes H. de Vreese, and Natali Helberger. 2016. Should we worry about filter bubbles? Internet Policy Review 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).