Digital-native news organizations in Latin America are emerging at a steady-pace, growing their audiences and influence. The digital environment in Latin America created an opportunity for renewal and innovation in journalism, including the potential for new media organizations to address original topics to the news agenda once ignored by traditional mainstream media (

Higgins Joyce 2018) and new opportunities for investigative journalism (

Palau-Sampio 2020). In Colombia, a study showed that about 80% of news organizations online are digital natives, having emerged in the online environment (

Consejo de Redacción 2018). Digital-native news organizations are bringing a major shift in news ownership concentration, accessibility to a wider range of audiences, and a change in how journalism is produced and presented. Given high concentration of media in Colombia and traditional ties with business and political elites (

Forero et al. 2009;

García-Perdomo and Magaña 2020;

Montoya-Londoño 2014), digital-native news media, by necessity and by opportunity, were able to break away from the business models that allowed for alternative funding. According to a study by the Reporters Without Borders and the Federación Colombiana de Periodistas, almost 4 out of 5 Colombians access information provided by the eight largest media groups, who concentrate 78% of cross-media audiences in the country (

Reporters without Borders 2021). Advertising online still lags, and digital natives such as La Silla Vacía opted for diversifying funding such as those originating from workshops and conferences, consulting and international organizations and awards, crowdfunding in addition to advertising (

Zuluaga et al. 2020).

This same process that has permitted for the emergence of many digital-native news organizations, allowing for greater diversity of voices and perspectives (

García-Perdomo and Magaña 2020;

Higgins Joyce 2018), has contributed to audience fragmentation and greater social polarization (

Trilling et al. 2017). A recent study shows that almost half of Colombians perceive their country to be in heightened political polarization than twenty years ago (

IPSOS/BBC 2018). While many studies have focused on the divisions that are emphasized in the digital media environment, as we go from an era of “mass” media to one of “niche” media, little attention is given to how digital media can bring diverse groups closer together in the public sphere. This study seeks to explore the role of digital-native news organizations in providing a common ground within this polarized environment, building consensus.

Correlation is a function of news media that, by connecting different groups of society together, or building consensus, could aid mobilization and prevent social threats (

Lasswell 1960). Consensus building studies infer differences within diverse demographic groups and look for instances when news media use reduces them; as individuals increase news media exposure, differences in attitudes and opinions between divergent groups, such as men and women for example, diminishes and agenda agreement increases (

Higgins Joyce and Khani 2019;

McCombs 2004). We know that television, newspaper, and radio are all able to bring opposing demographic subgroups closer together in what issues they thought were most important, and how they thought about issues and communities (

Higgins 2009), but less is known about how news organizations on social media could bring demographic groups closer together into consensus. Given the prominence of news media access through social media and the interplay of social media preference algorithms that tend to re-emphasize like-mindedness and echo chambers (

Geiß et al. 2018), understanding how consensus building can work in a networked digital news media environment is important. Consensus building has been tested in the US, Europe, and Asia, but the theory lacks testing in Latin America. While the context and media operate quite differently in Latin America, providing a common ground for deliberation of important issues is especially relevant in the young democracies of the region. This study explores the consensus building potential of a digital-native news organization on social media in Colombia.

Specifically, this study explores the assumption that digital-native news organizations from Colombia can create a common ground between men and women in their perception of Venezuela, in how they think about it (substantive dimension) and in how they feel about Venezuela as a news topic (affective dimension). The timeframe of this study, 2018 to 2019, marks a period of economic and political crisis intensification in Venezuela. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, by 2019 there were an estimated 4 million Venezuelan refugees, with the neighboring Colombia being the host country receiving the largest segment of those migrants, 1.3 million (

Council on Foreign Relations 2019). According to the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Relations, in addition to the 1.3 million Venezuelans migrating in 2018, a little over 1 million migrated to Colombia in 2019 (

Migración 2021).

While traditional media had the potential of creating common ground by expanding personal agendas of different socio-demographic groups (

Shaw and Martin 1992), mass media lacked the diversity that we find currently with the advent of the internet, including gender diversity. Yet, while the internet has allowed for greater access and potential for diversity, a recent study found that, in Latin America, national audiences for digital-native news organizations were more likely to be male (71%) (

Higgins Joyce and Harlow 2020), and that gender gap exists in online political discussion (

Van Duyn et al. 2019). This study seeks to explore the potential of digital-native news in creating common grounds between men and women in online political discussion.

This study then explores how this salient issue/topic of Venezuela is presented by a digital-native news organization’s social media in Colombia and if this news organization can bring diverse audiences closer together in deliberation of this issue.

1. Digital-Native News in Latin America

Digital-native news organizations in Latin America are increasingly relevant in terms of numbers, scope, innovations, and independence (

Higgins Joyce 2018;

Salaverría et al. 2019). In Colombia, they have challenged the local news industry by bringing up topics previously not covered (

Trujillo and Montero 2019), provided alternative voices to mainstream media (

García-Perdomo and Magaña 2020) and developing new business models (

Harlow 2020). They are also becoming a more popular phenomenon in Latin American journalism, growing its audience, and being recognized for the quality of their work and independent stance (

SembraMedia 2017). While the establishment of digital-native news organizations in the past decade is not an exclusive Latin American phenomenon, the extent of news media ownership concentration with close ties with powerful elites in the region influenced how these news organizations developed (

Trujillo and Montero 2019).

Digital-native news organizations emerge without previous connection with print or broadcast news media, although many of its founders and journalists have previously worked in legacy media in the region (

Trujillo and Montero 2019). With lower barriers to test new ideas, as costs are lowered and expectations not molded into the audience collectives, these organizations in Latin America innovate in many ways. With new platforms, journalists create journalism that is still tied to many of the traditional norms, while bringing in changes to how journalism is produced, who it is produced for, and the relationship with audiences (

Trujillo and Montero 2019). A study comparing journalistic role performance of print and digital native news organization in Chile found that media affordances significantly influenced how journalists work, but that audiences and beat had a greater impact (

Mellado et al. 2018). The Chilean study found a higher presence of watchdog role for digital-native news organization and loyal-facilitator for print media, which the authors link to differences in ownerships, given market concentration of print media and economic ties to covered news in that time-period (

Mellado et al. 2018).

These digital-native news organizations also innovate with their storytelling formats, how they relate to their audiences and distribution channels (

Méndez et al. 2019). A study of audiences for digital-native news sites in Latin America found both national and transnational audiences seek these outlets for community engagement, the technology included and the type of content they produced, in addition, transnational audiences sought community engagement through them (

Higgins Joyce and Harlow 2020). Social media remains an important channel for distribution and audience engagement for digital native news organizations in Latin America, with roughly four in ten Latin Americans reporting preferring to view news on social media first (

Newman et al. 2019).

Colombia is one of the top 20 countries in the world in terms of social media use, with 69% of the population actively using it (

Statista 2020a). Latinobarómetro’s 2018 survey indicated that 77% of Colombians used some type of social media, with 66% of Colombians using Facebook (

Latinobarómetro 2018). The high use of social media, alongside the growth of internet access in the last decade came with the relative political and economic stabilization: between 2001 and 2011 the country almost doubled the size of the middle and upper middle classes (

Straubhaar et al. 2015). That increased availability of internet, via computers or via cell phones, as is often the case, has allowed for an expansion of digital-native news organizations in Colombia. This has permitted that a plurality of news outlets and perspectives to be available throughout the national territory, a particular innovation in Colombia, where traditional media had been limited by “the country’s topography, large distances, economic and political interests and technical limitations,” (

Consejo de Redacción 2018, p. 68). In Colombia, a country whose print media emerged as family controlled with intrinsic ties to politics, dominating both Liberal and Conservative parties (

Hallin and Papathanassopoulos 2002), the advent of the internet has allowed for new organizations, voices, and perspectives.

Montoya-Londoño (

2014) calls the current media system in Colombia a captured liberal model, where the interests of media owners, political groups and influential actors are still present in a commercial system. The author also mentions the importance of the internet in allowing for new media projects to emerge and increasing journalistic supplies nationally (

Montoya-Londoño 2014). While not all digital-native news projects offer new voices and perspective, some the emergent and important independent news have surfaced in the past 20 years

.In a study of digital-native news organizations in Colombia,

García-Perdomo and Magaña (

2020) analyzed the implementation of digital technologies and innovations in newsrooms and found that they are ‘creative laboratories’, using “digital technology to produce editorial innovations, engage audiences, and rescue traditional journalistic values that are jeopardized by traditional news media’s structures and practices.” (p. 3089). Such is the case of La Silla Vacía, the news organization that this study analyzes. In a study comparing immigration coverage from Latin America between 2014 and 2018,

Severino (

2020) found that in Colombia, news organizations placed more focus on a Political Responsibility- Policy Solutions frame. Contrasting digital-native news organizations with traditional news organizations, the author found that digital natives emphasized the Political Responsibility frames to a greater extent and the Victim—Political and Economic frame to a lesser extent, focusing instead on the coverage of immigrants once in Colombia, rather than the push factors causing the flow of immigration (

Severino 2020).

The Colombian La Silla Vacía, founded in 2009 by Juanita León with financial support from foreign foundations such as the Open Society, is one of the country’s most accessed web portals with over 1.3 million unique users. It is also deemed one of the most influential news organizations in the country (

Alba 2019;

Trujillo and Montero 2019). Harlow and Chadha explored how social identities of digital-native founders shape their news ventures and identified the Guardian category when founders emphasized the production of quality journalism (

Harlow and Chadha 2019). Although that study focused on digital-native entrepreneurial journalism in India, that category seems to fit well La Silla’s goals. Having a woman as founder and owner of a news organization is highly unusual in Colombia and opens the possibility that this founder identity may also influence that news organization’s news production. La Silla Vacía is an independent, digital-native news organization with a focus on politics, and people in power (

Consejo de Redacción 2018). The news organization states that it “investigates and accurately describes how political power is exercised in Colombia,” (

García-Perdomo and Magaña 2020, p. 3083). Its strategy is constant innovation, close contact with audiences, and binging in new sources and perspectives in the coverage of politics (

Trujillo and Montero 2019). The news organization runs a for profit operation and innovates in its diverse funding strategy which still counts on grant funding, but more heavily counts on workshops, crowdfunding and also advertising (

Rosique-Cedillo and Barranquero-Carretero 2015;

Zuluaga et al. 2020).

While the internet has enabled the emergence of independent news media, with the potential of bringing much needed diversity of topics and perspectives, it has also allowed for audiences to self-select into news outlets more congruent with their own perspectives. In Colombia, the 2018 presidential election re-enforced polarization of earlier peace debates (

Carothers and O’Donohue 2019, p. 153), while the Venezuelan immigration crisis emerged as a salient issue in the region.

It is then, within this polarized climate that this study addresses Colombian digital-native news presentation of the issue of Venezuela. It seeks to explore the assumption that digital-native news organizations may have the potential building common ground among men and women. In earlier decades, mass media provided news and information with few alternative and marginalized voices. In Colombia, high levels of media concentration also meant that news and information was brought through the perspective of a few powerful groups. While limited in perspectives, mass media was able to bring divergent groups of society closer together into deliberation. The consensus building assumption has been tested and support found in the United States, Europe and Asia (

Shaw and Martin 1992;

Chiang 1995;

López-Escobar et al. 1998;

Higgins 2009). This study expands on the literature by testing the assumption in a polarized environment, in Latin America, and within a changing news media landscape. It tests for the consensus building potential of a digital-native news organization within its social media platform in Colombia.

2. Consensus Building in a Digital Environment

Communication scholar Harold

Lasswell (

1960) identified correlation as one of the basic functions of mass media. Correlation works by connecting different groups of society in response to a mediated environment, such as that presented by news media, building consensus and providing social stability. Individuals broaden their perspectives through exposure of issues and attributes of those issues brought by news media, gaining a more inclusive understanding of society, which then enables sharing of common ground with different groups of society (

Palmgreen et al. 1980). Consensus building occurs with the prioritization, selection and presentation of a limited set of issues and attributes of those issues, a consequence of agenda-setting effects (

Higgins 2009). It infers differences in attitudes and opinions between diverse demographic groups such as women and men, for example, and look for instances when news media use reduces such differences and agenda agreement increases (

McCombs 2004). Achieving a basic common ground on important topics that need to be addressed is necessary for a functioning democratic political community (

Geiß et al. 2018).

Previous research on consensus building found that television, newspaper and radio, to some extent, were all able to bring opposing demographic subgroups, such as gender, race, education and location (rural/urban), closer together in what issues they thought were most important (first level of agenda setting), and how they thought about issues and communities (second level of agenda setting) (

Shaw and Martin 1992;

Chiang 1995;

López-Escobar et al. 1998;

Higgins 2009). These studies found support for consensus building within a mass media environment. Much less is known, however, about how consensus building works within a digital, networked environment. A German study found evidence of consensus building within a digital environment, and that the effect was more prominent with those with more extreme political positioning than for moderates, where exposure to news media broadened their horizon of issues and facilitated a common ground (

Geiß et al. 2018). That study also pointed to a minority of population who are opposed to the news media and abstain from its use, which in case social media and interpersonal discussion seemed to further the divide and impede a common ground (

Geiß et al. 2018). Studies of consensus building have tested the assumption in the United States, Europe and Asia, but it lacks testing in Latin America.

Scholars have questioned if the consensus building consequence of agenda setting increases public’s focus on issues that need to be addressed if they are broadening personal agendas (

Edy and Meirick 2018). In the seminal consensus-building study,

Shaw and Martin (

1992) demonstrated that it was not that the process was bringing both segments of opposing demographics (such as men and women) closer to the media’s agenda, although that happens in some cases, but that the increased exposure to the news media decreases differences in prioritization of issues between the opposing demographic groups. With that, considering, for example, that men and women may have differences in what they think are important issues that need to be addressed, by being exposed to a wide range of issues presented by news media, men might broaden their personal agendas by sharing some prioritization of issues made by women, who might in turn be broadening their personal agendas. This exchange might provide enough common ground between those two demographic subgroups necessary for democracy.

While women are active consumers of Facebook in Colombia, 51% of Facebook users in that country are women (

Statista 2020b), studies suggest that there is a gender gap in online political discussion (

Van Duyn et al. 2019). Scholars have indicated that national audiences for digital-native news organizations were more likely to be male (

Higgins Joyce and Harlow 2020). In a study conducted in the United States, scholars found women were less likely than men to engage in state, national or international political topics online (

Van Duyn et al. 2019). Scholars have also found links between gender and perceptions of immigrants in Europe and the United States (

Fetzer 2000) and have theorized that women may feel more affinity with immigrants.

Luedtke (

2005) found that women were more likely to support harmonization of immigration policy in Europe. A secondary data-analysis of the World Values Survey 2018 found that Colombians presented significant gender differences both in terms of political values and opinion towards immigration policies (

EVS/WVS 2021). A one-way between subjects ANOVA was conducted and there was a significant effect of gender on valuing a democratic political system, with men (

M = 1.75) placing more value on democracy than women (

M = 1.88) [F(1, 1519) = 5.890,

p = 0.015]; and also on valuing a system governed by religious law, with women (

M = 2.65) placing more value on religious law than men (

M = 2.82) [F(1, 1519) = 7.512,

p = 0.006]. There was also a significant effect of gender and perception of essential elements of democracy with men (

M = 7.00) more likely than women (

M = 6.42) to state that it is essential to choose their leaders in free elections [F(1, 1519) = 10.874,

p = 0.001]; and also with men (

M = 6.04) more likely than women (

M = 5.29) to state that it is essential to have civil rights to protect people’s liberty against oppression [F(1, 1519) = 18.817,

p < 0.001], A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between gender and immigration policy preference among Colombians. The relation between these variables was significant, χ

2 (3,

n = 1520) = 9.236,

p = 0.026. Women were more likely than men to prefer policies that restrict immigration, for example “prohibit people coming from other countries”, where 16% of men stated that preference and 20% of women stated that preference. World Values Survey point to differences of political values and immigration opinions between men and women in Colombia but unlike the European and studies from the United States, women were less likely to support immigration. This study then looks for instances where news media use, through a digital-native news organization’s social media platform, would diminish such differences and bring men and women closer together in a common ground.

Given the gender gap in political discussion and digital-native news use, and the differences in political values and perception of immigration between men and women, it is relevant to analyze, for those who do access digital-native news and engage in political discussion about immigration, if they are able to achieve more common ground.

A case study of older adults in Texas found that digital media and online news brought education, location and income groups closer together in a shared common ground in their perception of government (

Higgins Joyce and Khani 2019), demonstrating that consensus building can work within a digital environment. That study, however, did not focus on the access of news through social media, which is an increasingly common way of accessing news, and the main way of accessing digital news in Colombia. A study analyzing how agenda setting occurs within a networked, social media environment in Spain found that consuming news through Facebook influence individual in how they prioritize issues, but that those individual’s perception of important issues was different than what the general public deemed important (

Cardenal et al. 2019). Similarly,

Tremayne (

2017) tested for the competing theories of agendas in a networked environment, that of fragmentation versus homogeneity and found support for homogeneity between traditional news media agenda and news media agenda shared on Facebook. However, the author found support for fragmentation between traditional news media and Facebook media agenda (

Tremayne 2017). This study adds to the literature by assessing the transference of salience on social media, more specifically on Facebook.

Second level agenda-setting studies assert that media’s emphasis, selection and presentation of an issue/topic’s attribute affects how people think about that issue/topic, in other words, it is the transfer of salience of attributes from the media agenda to the public agenda of attributes (

Ghanem 1997). Attributes can be categorized within two distinct dimensions: substantive and affective. The substantive dimension can be categorized as descriptive categories (how people think about issues) and affective dimensions as an appraisal, reflecting tone (how people feel about issues) (

López-Escobar et al. 1998). In a study of news presentation of presidential candidates, López-Escobar et al. found greater support for consensus building within the second level of agenda-setting for the affective dimension, although both affective and substantive provided support for the hypothesis (

López-Escobar et al. 1998). This study seeks to address the substantive dimension, operationalized as topics within the issue of Venezuela, and affective dimensions, operationalized as tone, of agenda setting within a networked digital environment. It seeks to address the transference the two dimensions within the context of Venezuela, as an issue, presented by La Silla Vacía’s social media, a digital native news organization in Colombia, and its transference to its social media audience. This study then poses the following questions:

- RQ1:

- Was there a correlation between the substantive attributes emphasized by the social media posts about Venezuela by Colombian digital-native news organizations and the substantive attributes emphasized in the comments of these posts by the audience?

- RQ2:

- Was there a correlation between the affective attributes by the social media posts about Venezuela by Colombian digital-native news organizations and the affective attributes of the comments of these posts by the audience?

This study seeks to expand on the consensus building literature by exploring its application within a social media environment, an environment of networked communication. It seeks to investigate consensus building on how Colombians think about the issue/topic of Venezuela, or consensus building as a consequence of the second level agenda setting, with a case of La Silla Vacía’s Facebook audience. It poses the following question:

- RQ3:

- Does the use of digital-native news media through social media in Colombia build consensus among men and women on their perception towards Venezuela?

3. Method

This study used NodeXL to import Facebook data from La Silla Vacia’s Facebook page. Facebook remains one the most widely accessed social media sites in Colombia, with 61% of the population using it in 2018 (

Statista 2020a). This study imported all available posts and comments for a year: 15 February 2018 to 2019. The timeframe marks a period of economic and political crisis intensification in Venezuela: from hyperinflation, food shortages and protests in February 2018 to the controversial re-election and inauguration of Maduro in January of 2019, Juan Guaidó swearing himself as the interim president. This timeframe yielded a total of 1100 posts and 29,284 comments from La Silla Vacía. This study analyzed the text of the posts from La Silla, and the comments made available. It selected the posts and comments from that timeframe that included the words Venezuela or Venezuelans, the unit of analysis. La Silla Vacía had 36 posts, with a total of 731 comments to those posts. While these posts had to have either of the keywords, all of the comments to these posts were included in the analysis, regardless of whether it included the keywords. These posts and comments were analyzed to answer RQ1 and RQ3. In addition, to answer RQ2 on affective attributes, this study analyzed, through the LIWC software, all posts (1100) and all comments (29,284) published within that timeframe and contrasted it with posts that included the keywords Venezuela and Venezuelans (36) and all of the comments that included the keywords Venezuela and Venezuelans published within that timeframe, regardless of the topic of the post the comments referred to (485). The coding units analyzed here are the texts of the posts, representing the news organization coverage, on social media, of the topic of Venezuela, and texts of all comments, representing the engaged audience of that news organization. This study recognizes that many more audience members will have accessed these posts, and that only a particular segment of the audience chooses to engage with the posts. The comments stand, thus, as a proxy for engaged audience members. Many posts, as well as comments, included other visual elements such as emojis, videos, photos, and hashtags, but those are excluded from this analysis in all of the research questions. While the number of posts by La Silla Vacía about Venezuela is rather small in the year of analysis, it is congruent with the sample from

Severino (

2020), who concluded that La Silla Vacía’s focus on national power and politics de-emphasized the coverage of immigration in his four year of analysis, 2014 to 2018. In addition, the engagement of those posts, as seen in the comments analyzed here, are substantial for this content analysis.

This study conducts a quantitative content analysis, using both computerized and human coding. Content analysis is a useful method for examining communication messages and attributes of those messages and has been widely used for determining topics of news coverage,—what the news is writing/talking about—and determining what aspects of the topics are being emphasized and de-emphasized both in terms of substance and affective dimensions, and is a common methodology in a variety of theoretical frameworks such as agenda-setting studies (

McCombs 2004) and framing analysis (

D’Angelo 2018). Scholars have argued that blending computational and manual methods of content analysis can “preserve the strengths of traditional content analysis, with its systematic rigor and contextual sensitivity, while also maximizing the large-scale capacity,” (

Lewis et al. 2013, p. 34). It utilized human coders to answer RQ1 and RQ3, assessing the potential of the Colombian digital native news organization La Silla Vacía of bringing men and women closer together in consensus and transference of substantive attributes. An emergent coding system was used, where posts and comment topics were noted and defined as encountered to determine the coding categories, as opposed to an a priori coding, where codes are determined before the analysis (

Stemler 2001). The study found a total of 10 topics, and remaining topics were collapsed into “others”. For RQ3, audience members (those who comment on the post), were coded for their gender (male or female) either by their presented name in Facebook’s profile, or the gender they chose to identify as when creating their Facebook account. A second coder was hired and trained to perform an inter-coder reliability test on 15% (

n = 114) of randomly selected posts and comments. Intercoder reliability was measured with Krippendorff’s alpha and, after training and three sessions, the study achieved a reliable 0.90 for gender and an acceptable reliability of 0.75 for topic (

Krippendorff 2004).

To answer RQ1 and RQ3, this study performed a spearman rho correlation. For RQ1, this was a correlation between the prominence of attributes in the news media agenda on the topic of Venezuela (operationalized as Facebook posts from La Silla Vacía), in other words, what topics in relation to Venezuela were posted more frequently by the news organization, to the audience’s prominence of attributes (operationalized as the comments to those Facebook posts from La Silla Vacía), in other words, what topics were included more often by the audiences replying to those posts. To answer RQ3, this study performed a Spearman Rho correlation of attribute salience of men and women (operationalized as comments from men and from women to the La Silla Vacía’s posts related to Venezuela), and contrasted that with those media (operationalized as posts from La Silla Vacía related to Venezuela) and men and also media and women.

To answer RQ2, on the transference of affective salience from posts to audiences, this study employed a computerized content analysis, the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count text analysis application, available for Spanish, which runs sentiment scores for the posts and comment texts. The program categorizes the text as positive or negative and has been widely used in mass communication research (

Lachlan et al. 2019). The program calculates a positive and a negative score, which is the percentage of words within your unit of analysis (in this case, Facebook posts and comments) categorized as either positive or negative by the total number of words in the text (in this case, Facebook posts and comments). The program was used to categorize all posts from that timeframe, all posts mentioning Venezuela, all comments and all comments mentioning Venezuela. The scores are then averaged by the number of posts and the number of comments. This study then performed a time series cross-correlation in SPSS to see if the affective attributes of comments on Venezuela did indeed follow the affective attributes of post on Venezuela.

4. Findings

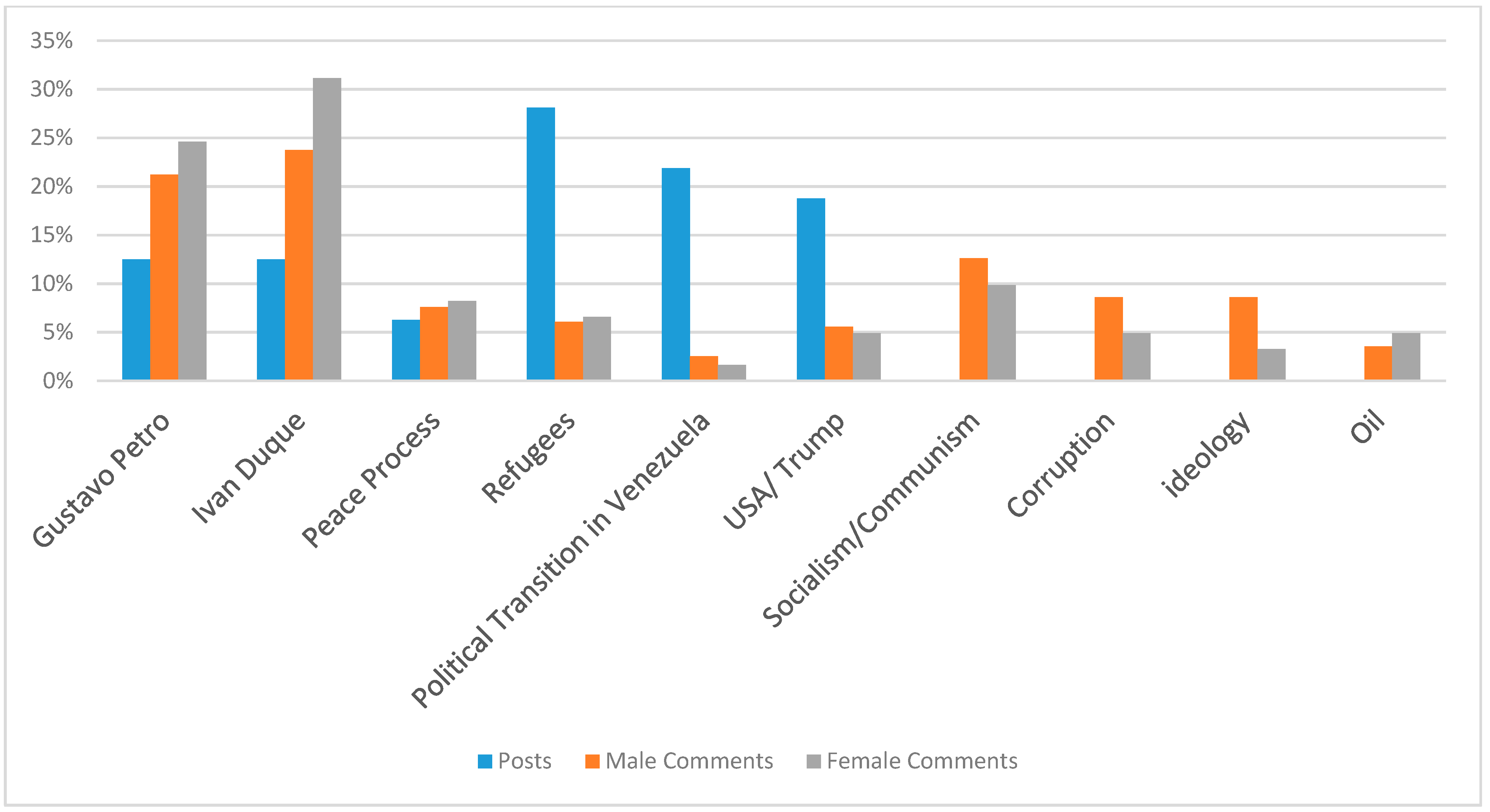

Out of the 36 posts that La Silla Vacía posted on its Facebook page about Venezuela in that timeframe, over one quarter mentioned the topic of migrants and immigration into Colombia and almost one quarter dealt with the topic of the political transition going on in Venezuela. The remaining half of the posts talked about the USA, in relation to Venezuela, and then, more locally, how local Presidential election candidates (Gustavo Petro and Iván Duque) reflected over current events in Venezuela. The comments, however, flipped the emphasis, with a quarter of comments relating to the Presidential candidate Iván Duque and 22% on the candidate Gustavo Petro. Comments also brought up other topics, such as socialism/communism (11%), Peace process (8%), Corruption (8%), Ideology (7%) and oil (3%), and only 6% dealt with the issue of immigration and 2% on the political transition.

Answering RQ1, which asked if the topics/issues posted by the Colombian digital-native news organization in relation to Venezuela were congruent with the topics/issues mentioned by the audience in the comments to these posts, this study finds a non-significant, weak, negative correlation (rs = −0.25, n = 10, p = 0.489) between attributes of Venezuela presented by posts and those presented by audience members in comments.

Men were more likely to comment on those posts than women. Out of the 731 comments, 70% of those engaging in comments were male and 24% were females, the remaining comments did not have an identifiable gender.

Figure 1 shows that the correlation between the topics surrounding Venezuela emphasized by the news organization’s posts (substantive attributes) and the topics emphasized by the comments made by men to those posts. These correlations were non-significant, negative, and weak (

rs = −0.30,

n = 10,

p = 0.407), indicating that the topics mentioned by men in the comments had little to do with the topics emphasized by the news organization’s posts. There was no correlation between the topic surrounding Venezuela emphasized by the posts and the topics emphasized by the comments made by women to those posts, (

rs = 0.03,

n =10,

p = 0.944). To test consensus building, following the seminal study by

Shaw and Martin (

1992), we look at the bottom of the triadic relationship, in the case of this study the correlation between men and women commenting on the La Silla Vacía posts about Venezuela.

Answering RQ3, this study finds a significant, strong, positive correlation (

rs = 0.76,

n = 10,

p < 0.05) between men and women on substantive attributes of the issue of Venezuela. Although both men and women do not seem to agree with the news organization’s posts in terms of the emphasis of the substantive attributes of Venezuela, they presented a strong agreement with each other. As

Figure 2 shows, while the posts from La Silla Vacía were more likely to mention topics such as refugees (28%) and political transition (22%) in posts about Venezuela, audiences were more likely to emphasize the political candidates Gustavo Petro (21% male, 25% female) and Iván Duque (24% male, 31% female). While there were some differences in how men and women emphasized different topics in relation to Venezuela, for example, men were more likely to mention ideology (9%) than women were (3%), and women were more likely to mention the candidate Iván Duque than men were, they do show a strong and significant correlation.

To answer RQ2, on the transference of affective salience from posts to audiences, this study employed a computerized content analysis, the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count text analysis application, available for Spanish, which runs sentiment scores for the posts and comment texts.

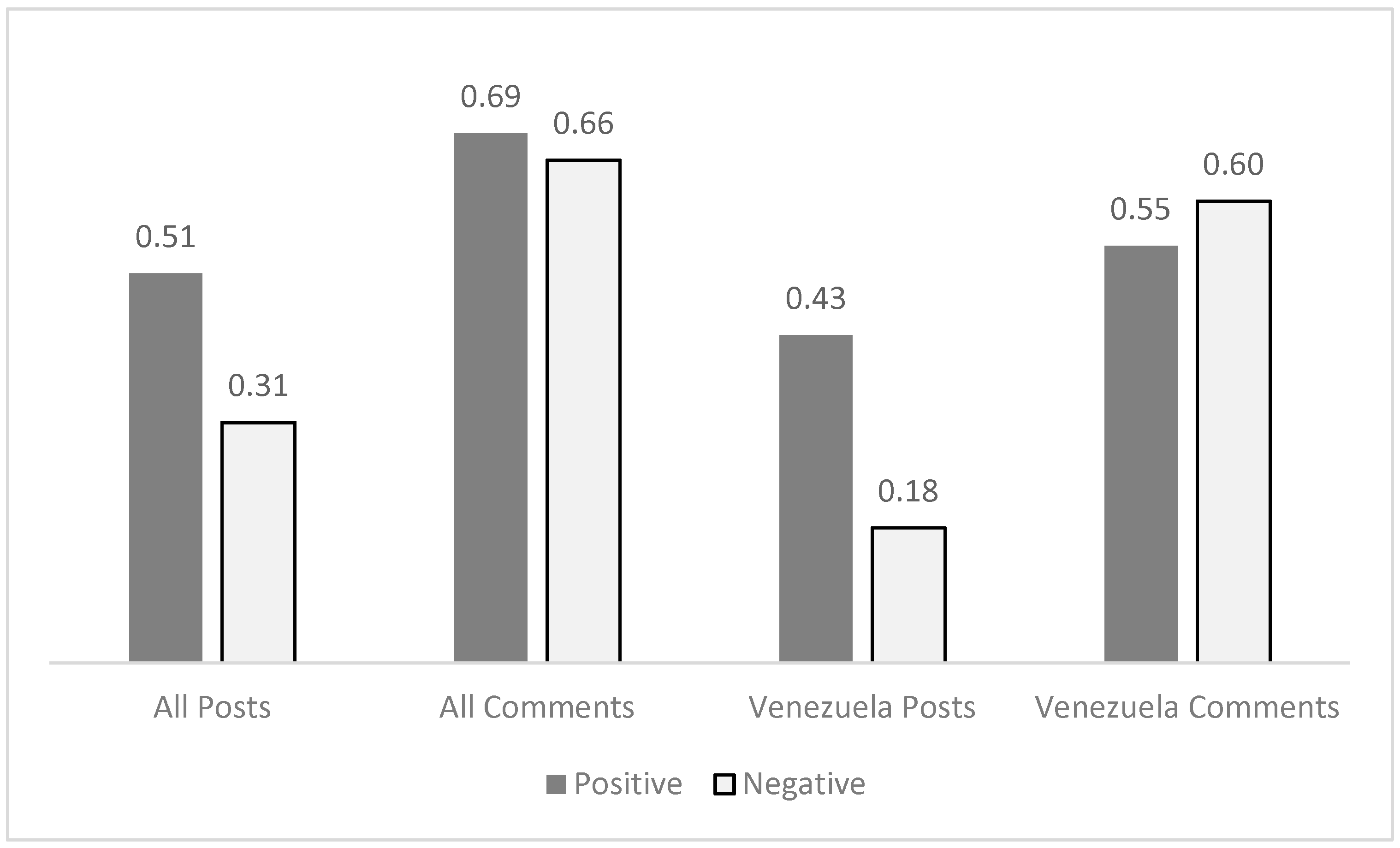

Figure 3 shows the average positive and negative tones of posts and comments. Considering the posts about Venezuela, this study found that most of the news organization’s posts were neutral, while also finding an average of 0.43 positive posts (SD = 1.02) by the news organization and an average of 0.18 negative posts (SD = 0.65) by the news organization. Considering the comments mentioning Venezuela from all posts, there was an average 0.55 positive comments (SD = 1.32) and 0.60 negative comments (SD = 1.35).

An example of a neutral post, defined as having a 0 score for positive and a 0 score for negative words, is a post from 10 February 2019. The post is a quote from an interview with Political Science professor Victor Mijares, published in the digital-native news site. The quote states “For me, the short term for Venezuelan transition is of one year” (author translation). While the news story may have a positive or a negative tone, the quote selected for the Facebook post was coded as not having negative nor positive words. A post coded as negative (with average negative words of 3.33) stated “More opportunity than from his own agenda. Even with the breathing room of the ELN attack and the situation in Venezuela, Iván Duque’s non-uribista flags still don’t take off” (author translation). The post linked to a story from La Silla Vacía on 7 February about President Duque’s initial 6 months in government. A positive post coded was “Although @petrogustavo maintains an admiration to Chávez and his work, and in addition having similar leadership styles, the Colombian context is very different than the Venezuelan one,” from 9 June, 2018. The post included an old photo of the presidential candidate Gustavo Petro with the former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez and linked to an article on the matter. The post was coded as having an average of 3.45 positive words and 0 negative.

To better understand if these affective attributes reflect the topic itself or not, this study also performed the analysis for all posts and all comments within that timeframe. It found that the average posts followed a similar pattern, with an average of 0.51 (SD = 1.46) of posts being positive and an average of 0.31 (SD = 1.05) posts being negative. However, when considering all posts and all comments, the comments are more likely to be positive. For all comments, an average of 0.69 (SD = 4.61) comments were positive and 0.66 (SD = 3.67) were negative. This indicates that the tone of comments in relation to the posts on Venezuela steered away from the norm in that year.

5. Discussion

Digital-native news organizations in Latin America in general, and Colombia in particular, are innovating within the news media environment in many ways. Many are engaging in closer contact with their audiences, with social media, events, chats, and other avenues. Some, as is the case of La Silla Vacía, the focus of this study, are demonstrating they can be successful in this new environment, growing audiences and providing quality journalism. La Silla Vacía’s focus on politics and power aims at bringing new angles and covering actors not usually covered in mainstream media.

Digital-native news organizations emerge within an online environment that is increasingly polarized in Latin America. In Colombia, the peace accord was marked by disagreement (

Carothers and O’Donohue 2019) that has continued in other areas of society. One of the main functions of media in society is to correlate different groups, building consensus (

Lasswell 1960). This study sought to understand the potential of a Colombian digital-native news organization to provide common ground among its audience within a social media environment. It explored the transference of salience of substantive and affective dimensions of the issue Venezuela from the news organization’s social media posts to its audience’s comments.

It found that, on the substantive attributes, La Silla Vacía’s Facebook posts prioritized migration and the political transition in Venezuela first, and then a focus on the local presidential candidates perceived the current issues in Venezuela, followed by other attributes. The comments on the Facebook page did not follow this prioritization. Comments overwhelmingly dealt with the front-runners of the presidential election: Iván Duque and Gustavo Petro. This study does not find a direct agenda-setting effect between posts to comments. Considering that La Silla Vacía’s focus is on local politics and power issues within Colombia, audiences may be carrying emphasis from other posts into the discussion of posts about Venezuela—in other words, considering that the news organization focuses quite extensively on local politics, once presented news posts about Venezuela, audience continue the discussion within a macro frame of the news organization.

In analyzing if La Silla Vacía was able to build consensus between men and women, this study found a positive, strong, and significant correlation between men and women on the topics they emphasized in the comments to the posts about Venezuela. While men’s comments had a slight negative correlation with the news organization’s posts and women had no correlation with the news organizations posts, men and women had a strong correlation between their comments. This finding suggests that the context provided by the news organization in general and the space provided for an opened discussion allowed men and women to find some common ground for deliberation of the issue of Venezuela. This finding expands on the consensus building assumption, originally proposed by

Shaw and Martin (

1992) and replicated in Europe (

López-Escobar et al. 1998;

Higgins 2009) and Asia (

Chiang 1995) by empirically testing the assumption in Latin America, within a Colombian digital-native news organization.

While we have gone from an era of mass media, with only a few dominant news organizations providing a common ground for a less diverse audience than we have today, to an era of media proliferation, which includes more diverse news producers and audiences, this study found that women were much less likely to actively engage in the discussions about Venezuela than men were. Less than one quarter of all comments were posted by women. While men have traditionally made the bulk of print audience composition in Latin America, especially in topics such as politics and foreign relations, women make up large segments of social media use (

Statista 2020b) and are increasingly accessing digital-native news organizations in Latin America. With more women as news producers and founders of digital-native news organizations (

SembraMedia 2017) and with La Silla Vacía having strong presence of women in the newsroom and leadership, the gap seems all that more relevant. Given the gender inequalities occurring in Latin America and the opportunities emerging from new women leaders in journalism organizations in the region, the gender gap in audience engagement through comments should be further analyzed.

However, for those women who did engage in political discussion, this study found that consensus building is possible within a social media platform of a digital-native news organization in Latin America. This study is limited by assessing only one news organization’s social media platform, and in one particular context (the issues faced by Venezuela at the time and the local, Colombian presidential elections), and replication is necessary. The study also has a limited scope, which limits some analyses. However, this study finds that the social media platform offers just enough common ground for men and women to deliberate on the substantive attributes of the issue of Venezuela that they deem important. In this case, men and women prioritized the local presidential election and debated on the issue of Venezuela with how they perceived the candidates to align or plan to deal with issues such as migration, its political regime, poverty and others. Facebook, as the social media platform used by the Colombian digital-native news organization, was a space where men and women could be exposed to and share attributes of an important topic, in this case Venezuela. While it is encouraging and beneficial to the health of a democracy that men and women do, indeed, find a space for deliberation and share some common ground for the discussion of political issues, it is important that more is done to understand the gender gap in political discussion and to further encourage women to engage in it. While this study points to the possibility of common ground for deliberation on a digital, networked environment, the environment for discussion is not encouraging women to participate at the same rate as it does men.

This study also analyzed the transference of affective attribute of Venezuela from the Colombian La Silla Vacía’s Facebook posts to their audience’s comments. It did not find support for the affective dimension. It found that posts by La Silla Vacía were overwhelmingly neutral. It found, however, that the news organization was more likely to present positive tones about Venezuela/Venezuelans than negative tones about Venezuela/Venezuelans. This is in alignment with the tone that the news organization’s Facebook posts were presented in other topics in that year. The audience, however, had comments to the posts about Venezuela with more negative tone than positive, and that was not the case in the overall commenting for other topics. This finding suggests that how audiences express themselves, in terms of tone, might be primed by how the posts are presented. Alternatively, given the differences in framing from digital-media, including La Silla Vacía, and traditional media on the topic of immigration (

Severino 2020), it is possible that audience’s negative tone may reflect legacy media’s coverage of Venezuela, while primed by the positive tone of the digital-native news organization. Given the implications for engagement and online environment, and the limitations of this study, this finding should be further analyzed within other contexts.

This study found evidence of consensus building between men and women in a social media platform of a digital-native news organizations in Latin America, La Silla Vacía, implying that digital media, much like mass media, may function to correlate different segments of society into enough agreement for deliberation. It does not find that the audiences necessarily follow the news organization in the affective nor the substantive dimension, but that the news organization provides audience space and some orientation for deliberation of an issue, in this case, Venezuela. By doing so, it has the potential of bringing opposing segments of society closer together, providing some common ground for deliberation. To do that, digital-native news organizations must accomplish an intricate feat: attract a diverse audience in an age of niche media and ensure that minority voices feel comfortable to participate and engage in the discussion. This study is, however, limited in its scope. Future studies should expand the news organizations, topics and demographic analyzed to have a better understanding of how consensus building works in a digital, networked environment in Latin America.