2. Materials and Methods

The sources for this study were: (a) Homer’s

Odyssey, original text in ancient Greek and translation in modern Greek poetry form by N. Kazantzakis and I. Kakridis, in order to select narrative descriptions of meteorological phenomena [

1]; (b) Mapzen Global Terrain [

2] and ESRI National Geographic USA Topo Map [

3], used to create Odysseus’ 10-year journey in the Mediterranean Sea; (c) the Earth’s axial precession theory for the orientation in Homer’s era in order to develop a wind rose diagram; (d) the Beaufort wind force scale for the corresponding wind velocity; and (e) Global Digital Elevation Model images [

4] for the depiction of Gape Maleas surroundings on the tenth day of Odysseus’ journey. Every verse rhapsody in the

Odyssey is referred to Fitzgerald’s English translation [

5] in the order of the

Odyssey book and verse assigned by Arabic numbers, e.g., (Od. 5, 296). Winds are depicted by arrows in certain locations, indicating their origin and speed in the Beaufort scale by their length. The map was developed via Quantum Geographic Information System software.

3. Results

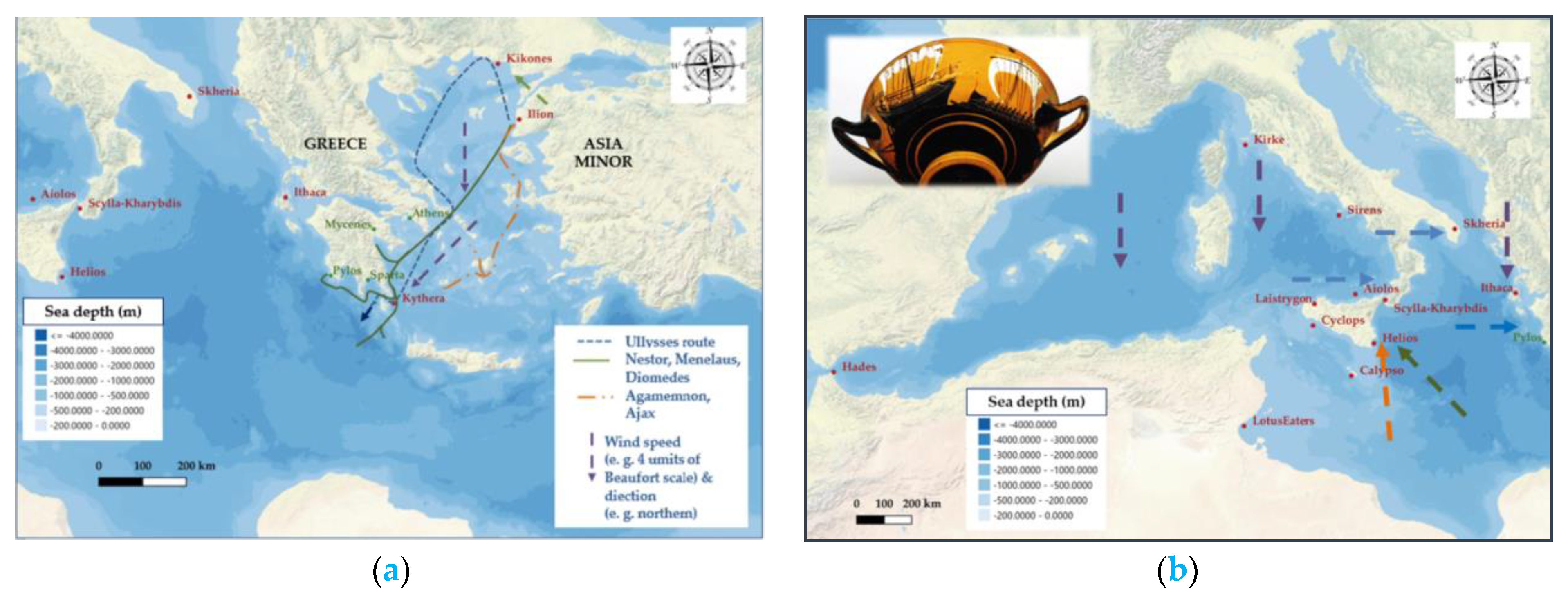

According to the prevailing approaches, Odysseus moves first to the Aegean archipelagos in the Eastern Mediterranean and then to the rest of the Mediterranean Sea, mainly in the area of southern Italy, and finally to the Ionian Sea.

After the fall of Troy, the Achaean fleet is divided and Odysseus with his ships follows a different route. In early summer, he sails close to the coast of Greece with the help of the etesian (summer annual) winds. The etesian winds have a north-northeast direction and blow in the Aegean with great intensity, mainly in July and August. When he reaches the area of Cape Maleas and Kythera, a sudden storm occurs, possibly due to the impact of a cold front which moves eastward since the appearance of cyclonic systems is frequent in summer. Several Achaean ships are driven to the coast of Egypt, while Odysseus’ ships are forced to follow a western direction, unable to return to Ithaca. This extraordinary meteorological phenomenon could be also the case of a strong microburst, which cause strong straight-line winds [

6]. Such a phenomenon can be on the scale of a few kilometers but has very serious effects on sailing ships in the open sea, since the wind speed can exceed 100 knots, i.e., 185 km per hour (

Figure 1).

In the epics of Homer, as in the works of Hesiod, meteorological phenomena are personifications or activities of the gods. Zeus summons the clouds, sends the rain, causes the storms, delivers the lightning and creates the thunder. The winds are controlled by the gods, Zeus, Athena, Poseidon and the nymph Calypso, who in turn can raise waves, cause storms, eddies and other winds. On the other hand, of course, they can safely guide the ships on their course (Od. 5, 21; 14, 305; 12, 415; 9, 67; 5, 382–385; 5, 291–296; 10, 19). The control of the weather, then, has great symbolic importance, and Homer’s descriptions serve as references for later meteorological analyses [

7].

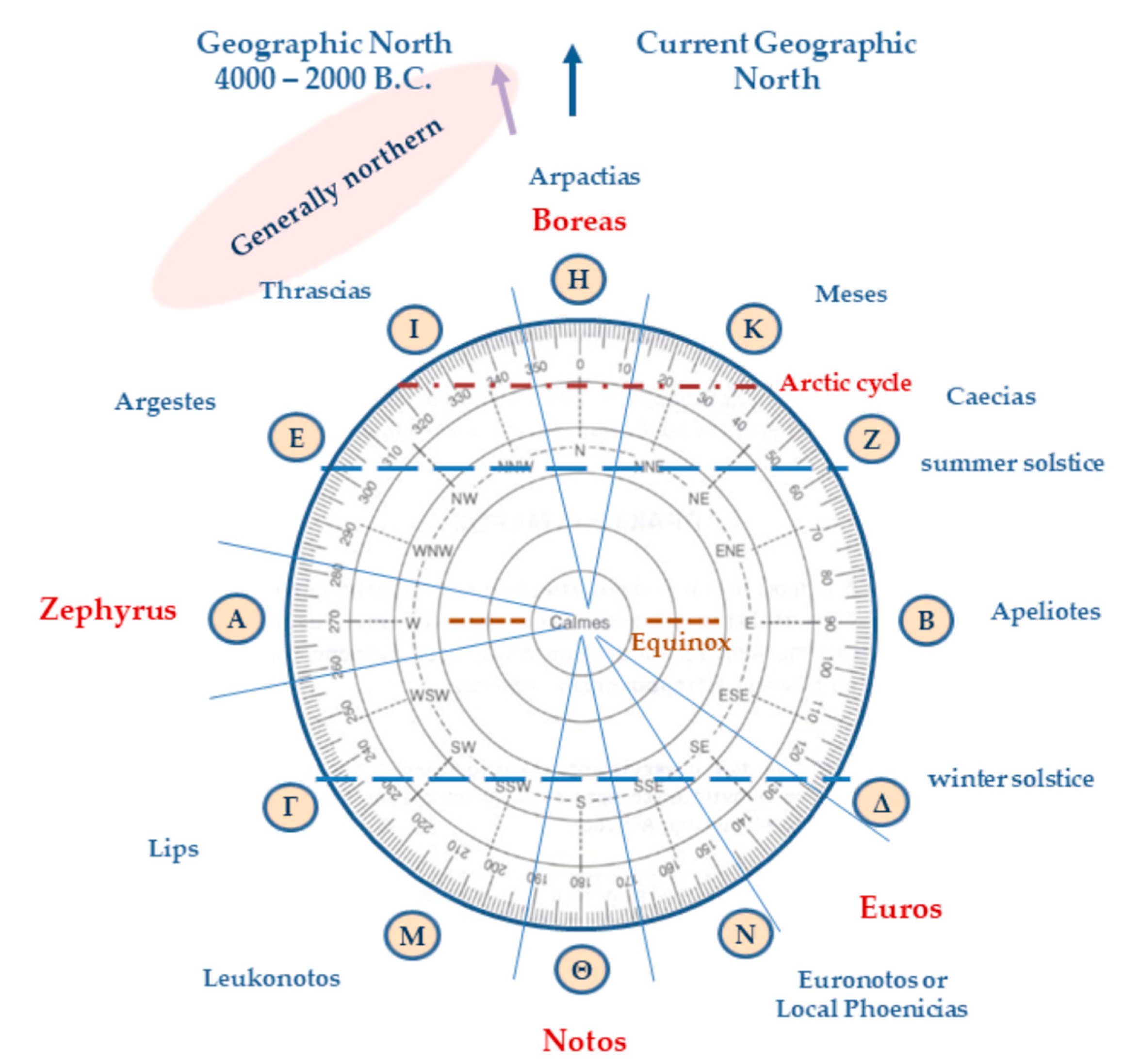

In Homer’s wind field conception, there are four main winds. It is Boreas, a particularly strong north wind, which blows from the Arctic North. The second is Notos (the south), a warm wind, in the opposite direction from the north. Zephyrus, also known as Ponentes, which blows from the west, appears as a fair wind but can also cause disasters. The last wind is named Euros, with a possible southeast or east direction, corresponding to Sirocco or the Levant. At this point, we must point out that at the time of the Homeric epics, the ancient Greeks placed the geographic north a little further west than its current orientation. That is, today the geographic north is located near the star ζ of Ursa Minor, which is also the polar star. It appears to be stationary, because all the other stars of the Northern Hemisphere appear to revolve around the North Pole in an east-to-west direction. At that time, there was no appropriate bright star to point to the north. Because Ursa Major, as Homer testifies (Od. 5, 301–303), was near the north pole of the celestial sphere, it revolved around itself and served as a marker for northward journeys. The ancient Greeks called the northern side of the horizon “arcton”. Thus, the winds that blow from the north are called northerly and that from the meridian southerly [

8]. From 4000 to 2000 BC, the geographic or astronomical north was near the binary star α of the constellation Dragon, always seen in the Northern Hemisphere, which is 3.7 times fainter than the brightest star of this constellation, γ Draconis. The change in the position of the geographic north is related to the precession of the Earth’s rotation axis. The precession, with a period of about 25,800 Earth years, is mainly due to the gravitational force of the Sun and the Moon on the Earth’s equatorial bulge.

Homer’s wind rose was expanded by Aristotle and Timosthenes of Rhodes with winds of twelve directions (

Figure 2), which correspond to respective circular sectors including the arctic circle, the line of the equinoxes and the solstices for the extreme points of sunrise and sunset at a location of latitude 40° N. The direction and intensity of the winds determine Odysseus’ journey by favoring or changing his course and ultimately causing his destruction. They are released from the bag of Aeolus when it is opened by the companions of Odysseus (Od. 10, 47).

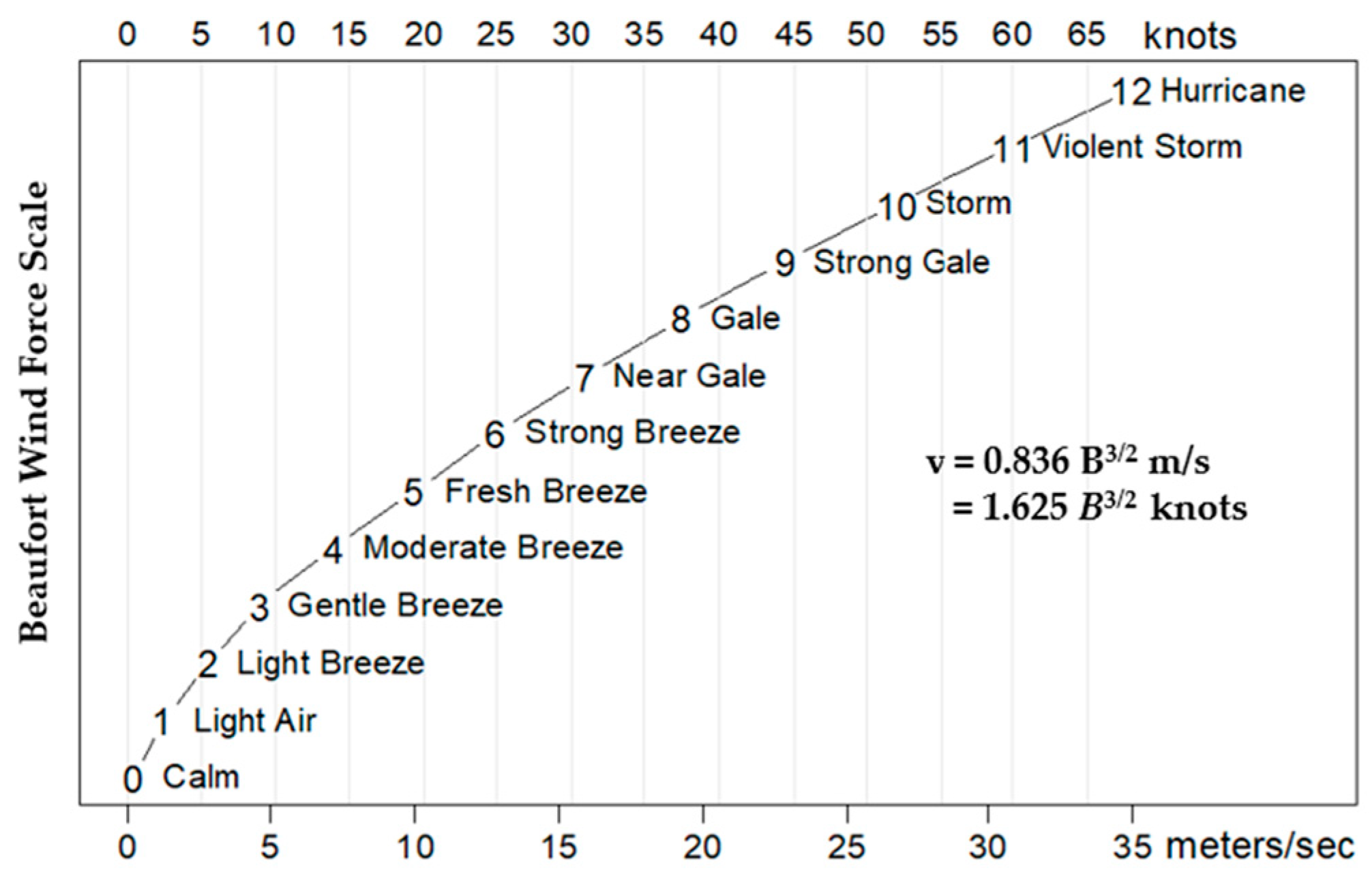

Their intensity, i.e., their speed, could be estimated via the empirical Beaufort scale according to the adjective verbal determination of the winds in the epic poem, e.g., breeze, fair, high, dashing, harsh, gale, stormy, hurricane, etc. (

Figure 3). Considering the adjective determinations of the

Odyssey’s winds’ intensity, we would estimate that these four winds can be strong (6 B) up to violently stormy (11 B), or even reach hurricane level (12 B), since the text mentions swirls and tornadoes. That is, their speed can range from 10 m per second (36 km per hour) to exceeding 30 m per second (110 km per hour).