1. Introduction

The water supply and sanitation (WSS) services have been considered human rights since 2010 [

1]. The importance of having access to safe WSS services was highlighted during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, since hygiene measures, such as hand washing, were some of the main adopted measures to prevent contagion [

2]. However, there are still many people in the world who do not have access to safe drinking water and sanitation services.

One of the great problems of the WSS sector is the discrepancy between current financing and future needs. To ensure universal access to WSS services globally by 2030, as established by the United Nations (Sustainable Development Goal 6), it is necessary to close this gap [

3]. WSS services should be available to everyone, and be safe, sustainable, affordable, and reliable. However, achieving this goal depends on investments in the magnitude of hundreds of millions of dollars [

4].

Financing endeavors in the WSS sector need to be increased, thus the private sector could be exploited and leveraged to ensure the deployment of investments required to achieve reliable services [

5].

The literature and research on financing the WSS sector have been gradually increasing [

5]. For example, one of the main research topics is focused on understanding how to attract the private sector and the characteristics that could be influencing its involvement [

6,

7], and another addresses financing mechanisms and models [

8].

To maximize the likelihood that a project will succeed, it is crucial to attract tailored financing for each type of project. This tailoring is important since there are several cases worldwide of privately financed WSS projects that were abandoned, did not yield the expected outcomes, or produced results that could not be sustained.

There is a strong necessity to understand how the characteristics of WSS projects could be influencing their performance and results. Thus, we decided to try to identify existing connections between project aspects such as type, applied financing solutions, performance characteristics, and results.

To carry out this analysis, it was necessary to choose a representative group of WSS projects. Therefore, it was decided to consult the extensive World Bank (WB) portfolio, and select completed projects financed by IBRD (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and/or IDA (International Development Association), between January 2010 and November 2021. This allowed to obtain a sample of 62 WSS projects.

There are four sections to this paper. After this brief introduction, in

Section 2, the methodological approach developed and applied in this study, to analyze and compare the characteristics and results of WSS projects financed by the WB, is described. Then, in

Section 3, the primary properties of the projects and their results are analyzed, through systematic quantitative review and comparative and statistical data analysis. The concluding remarks and future research expectations are presented in

Section 4.

2. Methodological Approach

A methodological approach was devised to enable the identification, retrieval, and analysis of WSS projects’ information.

It was intended to collect data from WSS projects, approved by the WB’s board between January 2010 and November 2021. So, some specific tags were used to retrieve information from the WB database, namely: “Water Supply” sector, “Sanitation” sector, “Closed” status, “IBRD” financing, and “IDA” financing. Projects fully financed by grants were not selected, as this study aims to study WSS projects that received repayable financing.

This retrieval allowed the use of data from 69 projects that benefited from one of the three types of current WB lending instruments, namely: Development Policy Financing (DPF; provides budget support to governments or political subdivisions, with a program of policy and institutional actions), Investment Project Financing (IPF; provides financing to governments for the creation of physical and/or social infrastructures), and Program-for-Results Financing (PforR; provides funds linked to the delivery of results that are defined in advance) [

9].

Some key data used in this study was automatically retrieved from the aforementioned database, namely: region and country of the project; the name of the project; the date the WB board approved the project; the closing date of the project; the borrower; the applied lending instrument; and the total cost of the project. In addition, through the consultation of vital project documents it was possible to collect the following additional information: project type; objectives; duration; commitments and disbursements from IBRD, IDA, and/or other entities; initial and final risk ratings; risk mitigation techniques; bank performance and result ratings according to the WB and an independent evaluation group (IEG).

Following its collection, the data was submitted to a systematic quantitative review. It was observed that some of the projects lacked the required information or did not fit the scope of the study (for example, some projects only received grants). Therefore, these projects were excluded, and the sample was reduced by around 10%. The remaining 62 WSS projects were submitted to a comparative and statistical data analysis. This analysis allowed to understand the potential influence of projects’ key aspects (that were identified during the systematic quantitative review) on the results of the projects and bank performance.

3. Results and Discussion

In the aforementioned timeframe, the WB (through IDA and IBRD) financed 62 WSS projects internationally, with the majority being from the East Asia and the Pacific region (34%) and the Latin America and the Caribbean region (23%). The WB only committed to finance one WSS project in 53% of the countries in the sample. The countries that received WB support in more than one project are the following: China (11 projects); Vietnam (5); Brazil (5); India (4); Bangladesh (2); and Niger (2).

In total 53 projects were financed through IPF, three through PforR and the remaining six through DPF. The regional distribution of the projects according to the lending instrument applied can be seen in

Figure 1.

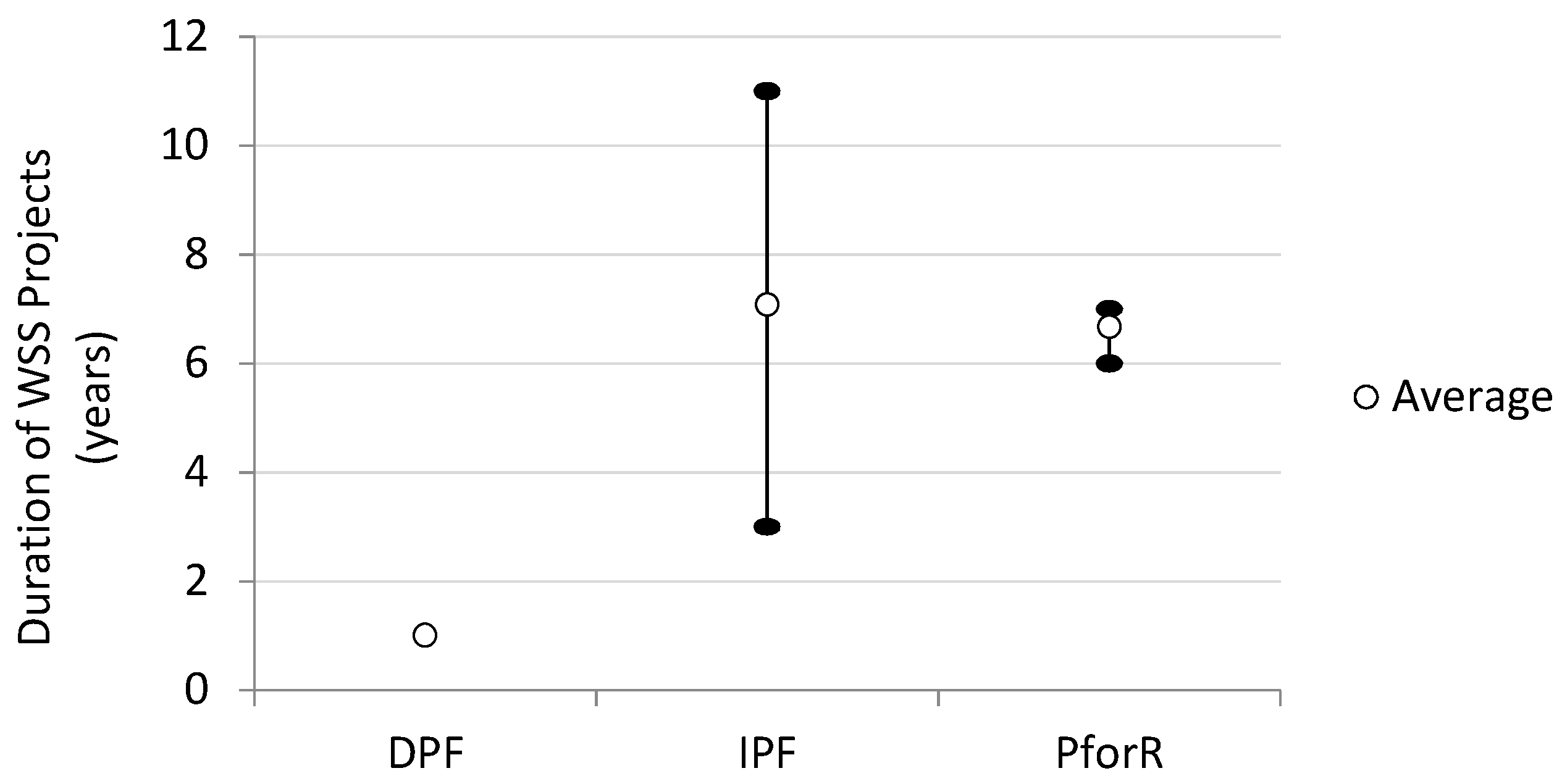

On average, the WSS projects were initiated in 2013 (median was 2012) and completed in 2019 (median was 2020). Thus, on average, the projects had a duration of 6 years (median was 7 years). More specifically, and as can be observed in

Figure 2, projects financed by PforR or IPF were, on average, 7 years long, and the ones financed by DPF were of short duration (1 year long).

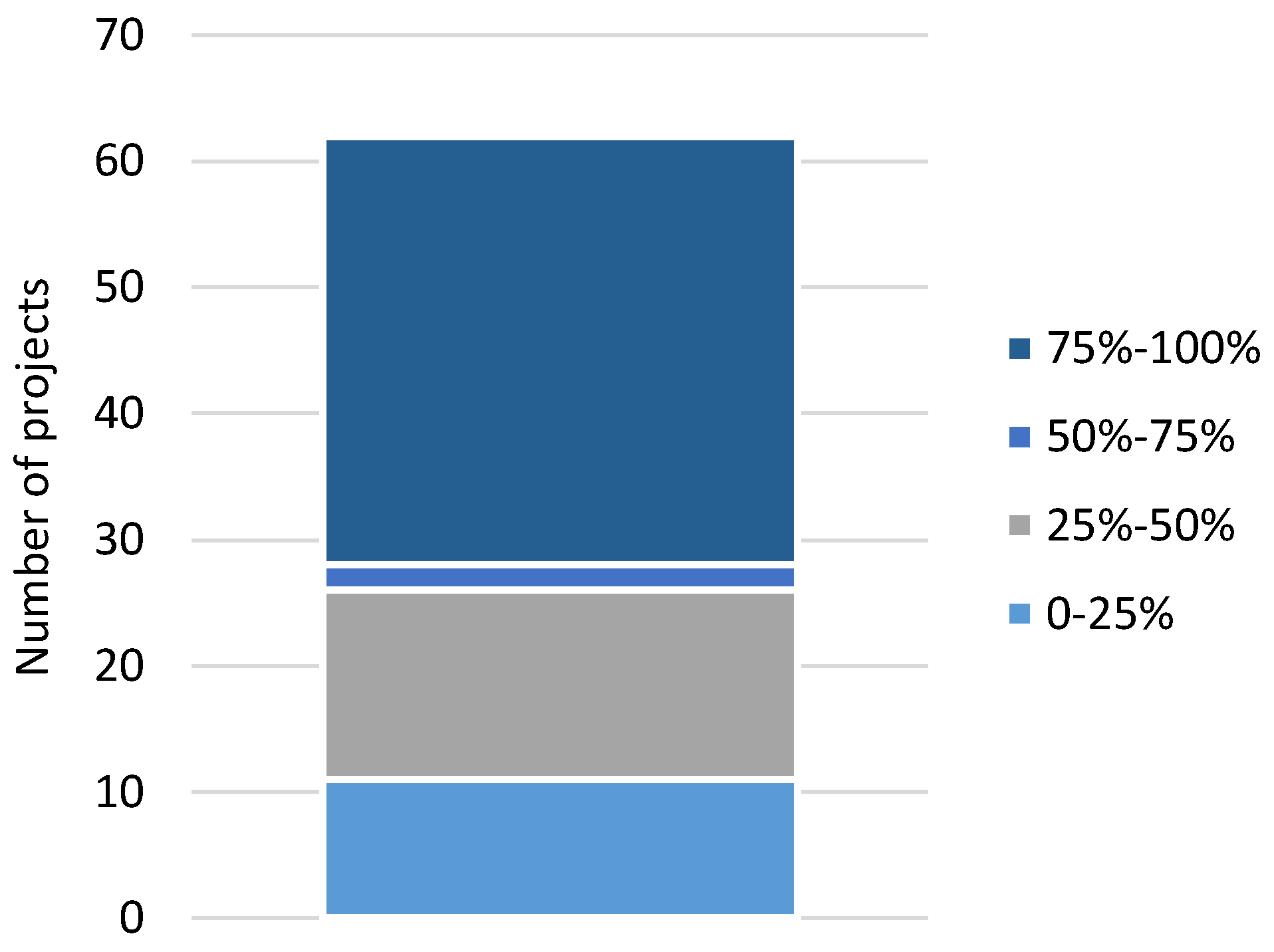

Not all of the 62 WSS projects are exclusively dedicated to the WSS sector. In fact, the majority of them are multidisciplinary (around 66%). So, for the purpose of this study, it was decided to characterize the projects according to their dedication (in percentage) to the WSS sector. The dedication to the WSS sector of the 62 WSS projects is on average 67%, while the average dedication of the multidisciplinary projects is 50%. The following

Figure 3 presents the number of projects grouped according to intervals of dedication to the WSS sector.

The 62 WSS projects benefited from commitments and/or financing from the World Bank (IBRD and /or IDA), and some of them also received commitments and/or financing from other entities. For example, while the projects that benefitted from DPF only received commitments from either IBRD or IDA, the three PforR projects in the sample received financing from several entities (i.e., one of the projects received commitments from IDA and a non-WB entity; another only received commitments from IBRD; and a third received commitments from both IBRD and a non-WB entity).

The commitments to the projects can be readjusted during their lifetime. Sometimes the revision of the values to be financed to a project result in the disbursement of more financing, and other times of less. In these situations, the projects present more than one credit tag issued by the WB (e.g., IDA-47440 and IDA-54310, from project P090157 [

10]).

The amounts disbursed by IDA and IBRD do not always equal the values originally planned. The discrepancy between project commitments and disbursements can originate due to several situations (e.g., reorganization of the project). It was observed that it was more common for the amounts disbursed by the WB to be inferior to the commitments than the reverse.

Next, the initial and final risk ratings of the projects (i.e., the risk ratings at the beginning and end of the projects) were collected and compared. However, it should be highlighted that, due to data availability constraints, some of the ratings used in the present project corresponded to the first and final ratings published by the WB (and not the actual first and final ratings). These ratings were calculated and attributed by the WB, through the application of its own tool, known as the Systematic Operations Risk-rating Tool (SORT). The SORT rates each type of risk as high, substantial, moderate, or low [

11].

The analysis allowed to observe that the average risk ratings of projects tend to improve, or at least stay the same, until the end of the project. For example, when analyzing the initial and final risk profiles of DPF projects, it was found that the risk ratings of one of the projects exhibited an improvement (changed from a substantial to a moderate rating) and the risk ratings of another three stayed the same. So, the risk mitigation techniques applied by the WB appear to be successful.

However, the analysis of individual risk ratings highlighted that this positive tendency is not always observed. In fact, risks that are not commonly identified and rated by the WB, typically, presented worst final risk ratings than initial risk ratings. This result may be due to the fact that these types of risks are only rated when they have a high impact on the project and are therefore more difficult to mitigate.

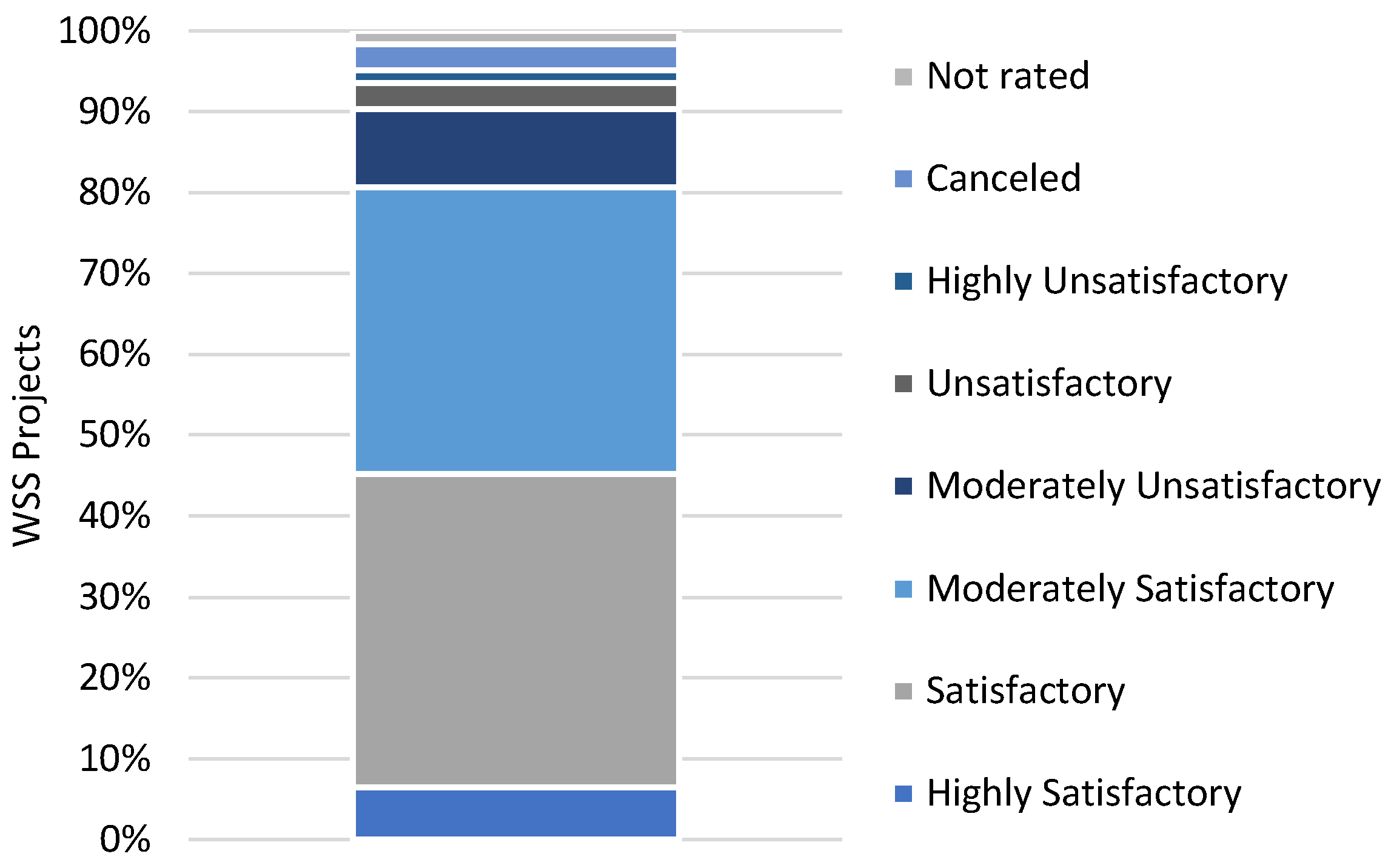

In the final phase of the projects, the WB (and sometimes, also, an IEG) proceeds with the evaluation and rating of the project’s result and the WB’s performance. According to both the WB and IEG, the average project result rating of the WSS projects was “moderately satisfactory” and the average WB’s performance was “moderately satisfactory”. Despite the fact that the WB and IEG ratings were frequently identical and fairly similar, it was observed that the WB ratings were tendentially more optimistic. The overall ratings of the 62 WSS projects, as determined by the WB, can be seen in

Figure 4.

After the identification and analysis of the key aspects that were mentioned, we proceeded with a comparative analysis aimed at assessing their influence on WSS projects’ results. Thus, we built a correlation matrix using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, with the help of the IBM SPSS Statistics software. The objective was to identify potential correlations between WSS projects’ key aspects and the projects’ results and verify some of the theorized trends and effects between variables. Some of the main results will be described shortly.

First, we proceeded with the verification that the ratings issued by the WB, regarding the project and its own performance, are reliable. This confirmation was essential because some of the projects were only rated by the WB (the IEG only rated the project’s results and WB’s performance of 65% of the projects). As a result, we found strong and significant correlations between IEG project result rating, WB project result rating, IEG rating of WB performance, and WB rating of own performance. Hence, it seems that the success of WSS projects could depend on the performance of their financiers, which, in this case, is the WB.

It was observed that lengthier projects (i.e., with longer durations) have better final project risk ratings (i.e., less average risk) and that initially riskier projects are sometimes lengthier. In addition, longer projects appeared to have some tendency to present better results. As expected, projects with less average risk at the time of completion presented better results and WB performance ratings. Therefore, it appears the application of risk mitigation techniques, to ensure lower risk ratings at the end of the project, could be very important for project success.

It is crucial to effectively plan projects, by correctly identifying the project’s objectives and planning how these will be achieved. This planning includes not only the identification of the tasks to be performed but also the monetary values required for their accomplishment. However, sometimes it is not easy to predict the project’s future needs. Often, the original circumstances change after the project begins. So, occasionally, the WB releases several credits. A comparative analysis allowed to determine that the number of different credits of a single project does not appear to influence the results of WSS projects.

It was also observed that higher commitment amounts do not ensure better project results. This observation held true even when the comparison was performed individually for each of the lending instruments applied by the WB.

Regarding the projects’ dedication to WSS sectors, it was not found a correlation between the percentage of a project’s dedication to WSS sectors and the project result ratings (only a negative tendency).

In addition, it should be mentioned that additional comparative analyzes were also performed with other project characteristics (e.g., different types of risk ratings, applied mitigation techniques, and success of WSS projects).