Abstract

In the majority of transboundary river basins, difficulties lay on common policy planning, and such is the case of Mesta/Nestos shared between Bulgaria and Greece, where both qualitative and quantitative issues could threaten the water safety. Conceptual models organize the available information, respond to policy questions, assisting policy makers in a simple yet practical way. The aim of this research is the application of the SWOT conceptual model to identify the major possible threats (gaps) to water security in the Mesta/Nestos transboundary river basin and assist in future steps prioritization regarding water policy arrangements. The results highlight the need for stronger bilateral cooperation, for common PoMs development, activities’ coordination to support the WFD implementation, and improving transboundary interactions in the basin.

1. Introduction

Water governance became a concerning global challenge as freshwater resources are under increasing stress due to human population and economic growth and other drivers [1]. The complexity of these challenges is even higher than more than 310 transboundary basins of the world [2], which inhibit approximately 40% of the global population [3]. This concerns, in particular, competitive uses of water and the involvement of different stakeholders with diverging interests over water resources, especially in times of the climate crisis, which requires, but also renders more complex, the need for sustainable and systematic water resource management [4] and the assessment of water governance problems and the identification of effective solutions [5], confirming the statement that “water crises are primarily governance crises” [4,5,6]. Water governance, moreover, is strongly linked to water safety, sustainable development, regional stability, and peace [7], reinforcing its importance.

The international river basins in Europe are regulated by the Water Framework Directive (WFD). The WFD adopts a governance and a river basin approach [8]. In cases where an international river basin is shared among member states, coordination needs to be ensured with the aim of producing a single international river basin management plan, thus sharing the responsibilities. If the basin extends beyond EU territories, the directive encourages member states to establish cooperation with non-member states and, thus, also manage the water resource at the basin level [4,6,9]. Although the WFD sets ambitious goals for transboundary cooperation in Europe, some implementation challenges persist. These are related to the shared responsibilities among water authorities, the administrative structure, the adoption of a common river basin management plan (RBMP), and stakeholder involvement at transboundary level [10,11,12].

Greece shares five such basins with three neighboring non-EU member states with differences in the progress of their accession processes. The basin management in all countries are governed by water resources availability and land uses/cover, while in Mediterranean Greece it is characterized mostly by water abstraction used for irrigation, having a reverse seasonal pattern to the water availability.

The WFD Implementation Report found that the stronger the governance of the river basin and the more developed the RBMP, the better the results in terms of achieving WFD objectives. Nonetheless, the Commission’s Implementation Report also found that there is still some room for improvement, for example on ensuring a harmonized approach for status assessment or the coordination of Programs of Measures (PoMs). In this context, there lies a gap in science to policy interaction [13] which could be bridged with conceptual models. Such models summarize and codify relevant information on the river basin in a hierarchical way. Given that the “official procedure” in reaching a common management plan is characterized by high complexity, a standardized methodology that could overcome subjectivity, group, and decode all available information in favor of communication, would be an asset. Conceptual models organize the available information, respond to policy questions, follow a logical framework, assisting policy makers in a simple yet practical way. A key condition for improved science–policy interaction, with a particular emphasis on improving water governance in transboundary basins, recognizing that science is a significant input into water resource decision-making processes [13]. A SWOT model could produce valuable outputs, giving insights into the current status of a research field, diagnosing the future critical points, which could be the possible inputs for policy and managerial implications [14,15]. Our research asks “what could be improved” in the Mesta/Nestos transboundary river basin, shared between Bulgaria and Greece during WFD era. We aim to identify and analyze the major water governance aspects in the basin, and to further track possible threats (gaps) to water security that could be of assistance for the prioritization of future steps. We focus on the WFD era (since 2000), as the timing is crucial since we are traversing the preparation of the third cycle of the RBMPs. To assess water policy arrangements a SWOT (Strength-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats) model was applied.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

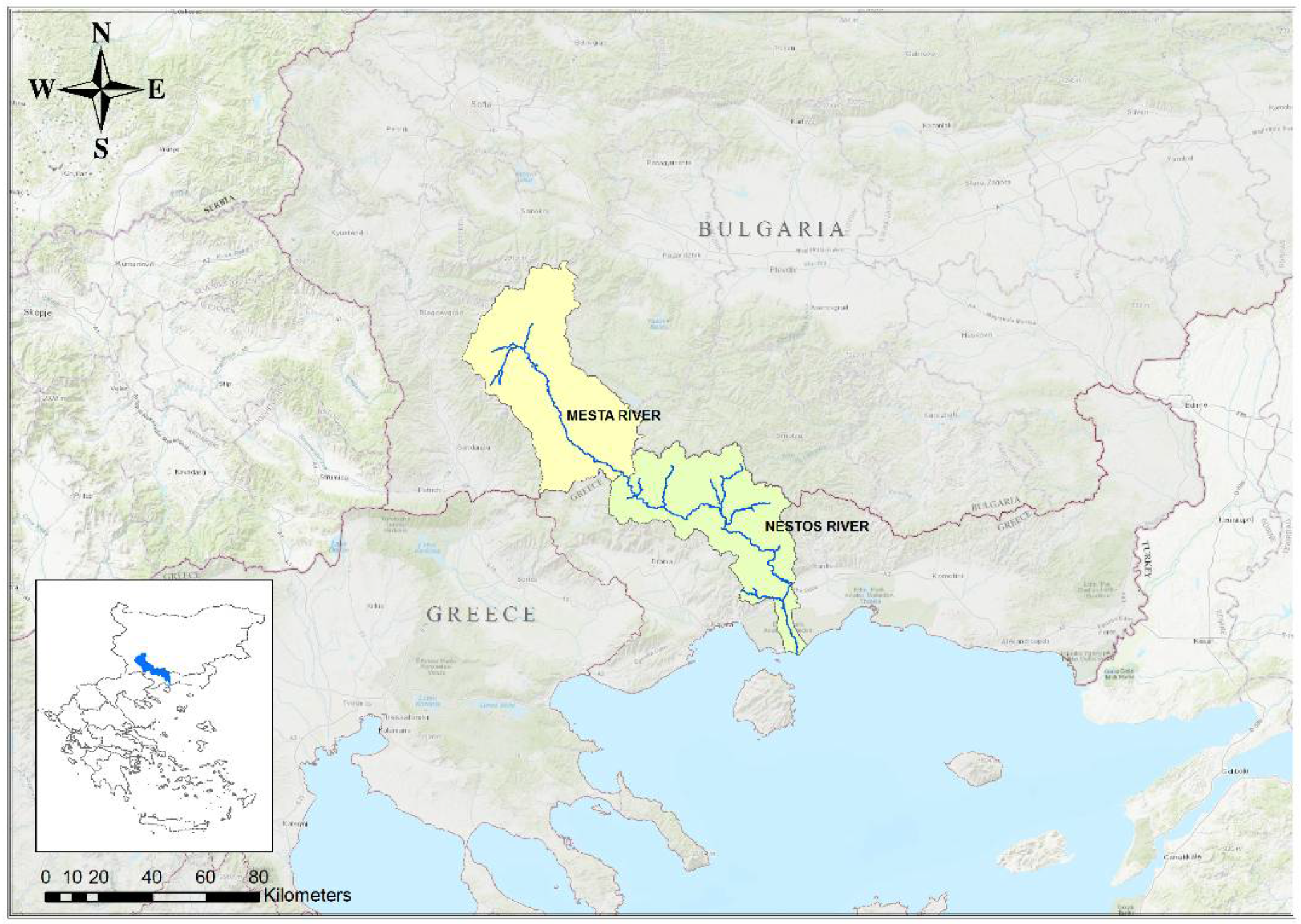

The transboundary river basin of Mesta/Nestos—the Bulgarian part is known as Mesta River while the Greek part as Nestos River—is located in southeastern Europe and is shared between Bulgaria and Greece (Figure 1). It is situated at the southwestern corner of Bulgaria and at the region of Macedonia and Thrace in Greece. Both countries are socially, economically, and environmentally connected to the water resources of the Mesta/Nestos River. Forestry, agriculture, industry, and the developing winter tourism are the main economic sectors in the region of Mesta River catchment, which are significantly connected to the water of the river Mesta. On the Greek part of the basin, the main uses of water resources from the river are the agricultural and the energy sector. In both parts, the natural environment, the biodiversity and the ecosystem services have great importance, since they occupy areas which are governed by special international environmental protection law [16,17,18,19,20]. As a result, ensuring the sustainability of the water resource in the Mesta/Nestos transboundary river basin is an urgent need.

Figure 1.

Transboundary river basin Mesta/Nestos.

2.2. Cooperative Status between the Two States

The Mesta River belongs to the national West Aegean River Basin District (RBD) (BG 4000) and the Nestos River to the national RBD of Thrace (EL12). The Mesta/Nestos River Basin is an international basin with a bilateral agreement since 1995, put in force for a pre-defined duration of 35 years [21]. The formal bilateral agreement between the States gives Greece the right to 29% of the total volume of water that is generated in the Bulgarian territories before entering Greece. According to the agreement, both parties have to exchange information concerning the water status and any development plans that would affect the natural flow of the river. A joint declaration was signed on 27th July 2010 for cooperation on the implementation of European Union water legislation and the water resources management issues in the transboundary basins between the Hellenic Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change and the Bulgarian Ministry of Environment and Water Resources. A Joint Expert Working Group was established. The Joint Working Group meetings took place in Drama (2011), in Sofia (2011), in Thessaloniki (2013), in Athens (2014), in Athens (2015), in Sandanski (2016), in Kavala (2017). It is important to note that there is a difference in the magnitude of this legal pact for each country. According to the WFD Implementation Report of Bulgaria (2019), the Mesta/Nestos River basin is designated as Category 3, that is, as an international river basin with an agreement in place. In the Greek Implementation Report (2018), the river basin belongs to Category 2, meaning the area falls under an international agreement and permanent co-operation body in place.

2.3. SWOT Conceptual Model

The SWOT conceptual model (Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats analysis) can be a key tool used for identifying, categorizing, and comparing all the internal (strengths and weaknesses) and external (opportunities and threats) factors related to a decision and strategic planning [15]. In this study, the SWOT model is applied as the logical frame for a better understanding of the major water governance aspects in the Mesta/Nestos transboundary river basin, by identifying the key priorities for increasing the water governance effectiveness and unpacking the gap in governance of the water resources in a transboundary setting. Strengths and opportunities govern priorities, while weaknesses and threats give an overview of the gap for water security in the basin.

Input data follow the WFD implementation, with the intention to find out the water governance factors that influence the implementation of the Directive 2000/60/EC in the basin, hoping that the results could be useful in multi-level water management, decision making and in the development of the third cycle RBMPs.

The implication of the SWOT model relies on the information analysis derived from a scoping review of official EU (European Union) and specifically WFD-related documents (Table 1). The information included in the official (institutional) documents from the two states, was grouped in three categories and then processed in a SWOT (Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats) model. Our analysis in three categories is followed by the main components of the WFD:

Table 1.

List of reviewed official documents.

- Environmental goals set by WFD, achieving “good” ecological status for the identified water bodies at the basin level. (Art. 4, WFD).

- National/Regional legal/institutional (Legislation scheme), encouraging the use of existing governance structures or set up new to coordinate actions in river basin districts and appointing a Competent Authority for each of the RBDs (River Basin District) to produce the RBMPs and to co-ordinate the implementation of the WFD within it [22], including the international river basin (transboundary cooperation). (Art.3, WFD).

- Public consultation, requiring public participation that different stakeholders should participate in the process of developing management plans. (Art. 14, WFD).

3. Results

After the inclusion of the available documents published on water management in Mesta/Nestos for both countries, a comparative Table (Table 1) was created to showcase the “effort” made during all the time since the WFD entered into force. Table 1 summarizes the type, the source and the date of the reviewed official documents, whose basic information is organized in the SWOT model (Table 2). Most documents come from the Bulgarian side but deal with reporting to the EU Commission and other organizations (OECD, UNECE, OSCE) on the steps made towards WFD implementation. There are fewer documents from the Greek side that they focus more on reporting on legally required actions. Augmented frequency of reports is observed from the Bulgarian side during the last years.

Table 2.

SWOT model-Water Governance in Mesta/Nesto Transboundary River Basin.

4. Discussion

This research aims to identify the main priorities and gaps in water governance, focusing on the WFD implementation in the transboundary river basin of Mesta/Nestos by analyzing all the relevant official documents and organizing the extracted information in a SWOT conceptual model. The lack of a common EU language in RBMPs hampers a comparative analysis. One of the WFD implementation challenge is the communication of the Directive objectives in a language that is meaningful to most stakeholders [23]. Firstly, we used a SWOT model to understand basin governance and, secondly, we showed that the use of SWOT model could be an effective approach to understanding and improving water governance. The SWOT model components are analyzed in pairs, as they are linked: strengths and opportunities which produce the priorities; weaknesses and threats which state the gap in water governance in the basin.

The results (Table 2) highlight the main insights of the water governance current status and the priorities that are likely to increase the chances for effective WFD implementation in the basin, as described in the SWOT model through strengths and opportunities. Regarding the current circumstances in the basin, the major strength is the harmonization of both national policies to EU water policy (WFD, EU Floods Directive, CIS, GD pillars), which includes the requirement for water (environmental) protection (“good” ecological status), clear administrative structures, and shared responsibilities among the relevant authorities along with public participation. Furthermore, the results point out a significant set of opportunities that could enhance WFD implementation in the basin. First, common knowledge and a better understanding of the grey infrastructure and the application of NBS (nature-based solutions), enhanced with the updated data (references condition, pollution points) could lead to better water management, resulting possibly in improved water quality and quantity for both sides. From an institutional point of view, the identification of common key priorities, the mobilizing of financial resources, recognizing the current weaknesses, and the establishment of bilateral conflict resolution mechanisms are seen as a great opportunity for sustainable solutions, providing the basis for win–win common PoMs. An enhanced participatory management can improve the socio-economic regional conditions, strengthen the cooperation and stability in the study area. The stakeholder’s awareness, the possible inter-sectorial synergies and the quantifiable feedback from the consultation process are among the basic opportunities (Table 2).

However, the findings further indicate a gap in an operational point of view, concerning water governance. We see that the combination of the weaknesses and threats describe the current and emerging challenges inhibiting WFD implementation. The lack of common international coordination PoMs activities, the poor PoMs implementation at national level and the absence of a common scientific database could lead to basin fragmentation and lack of river continuity with impacts on water conservation. This increases the risk of the “good” ecological status for all water bodies not being achieved by 2027. The centralized administrative structure in both countries and the overlapping responsibilities among water authorities, driven by the top–down water policy, constrain the compliance with the legislation scheme in the basin. Additionally, the delay on the RBMPs adoption, the different timeline of RBMPs (Bulgaria submitted its RBMP to the EC before Greece) for both states led to the lack of a common RBMP for the basin, which is a requirement from the WFD for the international river basins (Article 13, WFD) [9].

According to the WFD Implementation Reports, no bilateral public consultation took place, as a result no common vision for the future water resource uses was reported. The persistence of local characteristics (social, economic, cultural, law, politics, ecosystems approach) [24] and the poor level of stakeholder’s participation constitute, if not addressed cooperatively could lead to a possible conflict of interest over the water resource uses. Trying to reply to the research main question “what could be improved”, the current status reflected by the strengths and weaknesses of SWOT analysis, reveals the sum of the problems not confronted properly up to now. A main issue that could be highlighted is the lack of a parallel path resulting in no common strategy planning, monitoring, need prioritization, and mitigation measures. As for each country separately the level of compliance with WFD requirements is not optimal. Though future steps could be characterized by success, if possible, conflicts were confronted ex-ante (threats from SWOT analysis) and opportunities were fully exploited.

In conclusion, SWOT summarized and illustrated in a simple form all the available information concerning the critical points of the water governance in Mesta/Nestos River basin. In our research, it revealed the priorities and gaps in water governance, which are affecting the WFD implementation. As the third cycle of the RBMPs (2021–2027) is now in the preparatory and drafting phase, the outputs of our research could be an entry point to an improved science-policy interaction, responding to policy questions, following a logical framework, assisting policy makers in a simple yet practical way. More specific, in the Mesta/Nestos River basin, besides the partial compliance with the WFD from both sides and the opportunities that arises from it, yet there are gaps need to be addressed. There is a need for a stronger bilateral cooperation with enhanced public consultation and for the development of common PoMs with coordination activities in order to improve transboundary interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K., L.D. and K.I.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and L.D.; writing—review and editing, M.K., L.D., K.I. and S.S.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, K.I. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The assistance for the study area maps development provided by Ioan-nidou Parthena, DUTH was greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johns, C.; VanNijnatten, D. Using Indicators to Assess Transboundary Water Governance in the Great Lakes and Rio Grande-Bravo Regions. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 10, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, M.; Wolf, A.T. Updating the Register of International River Basins of the World. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2019, 35, 732–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. UN Water. Transboundary Waters. 2016. Available online: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/transboundary_waters (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Schulze, S.; Schmeier, S. Governing Environmental Change in International River Basins: The Role of River Basin Organizations. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2012, 10, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Palmer, M.; Richards, K. Enhancing Water Security for the Benefits of Humans and Nature—The Role of Governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Principles on Water Governance. Water Governance in OECD Countries: A Multi-Level Approach; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/governance/oecd-principles-on-water-governance.htm (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Jacobson, M.; Meyer, F.; Tropp, H.; Oia, I.; Reddy, P. User’s Guide on Assessing Water Governance; UNDP: Oslo, Norway, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, E.; Bortolini, L.; Defrancesco, E. Coordination and Participation Boards under the European Water Framework Directive: Different approaches used in some EU countries. Water 2019, 11, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Communities. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2000, L327, 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kessen, A.M.; van Kempen, J.J.; van Rijswick, H.F. Transboundary River Basin Management in Europe Legal Instruments to Comply with European Water Management Obligations in Case of Transboundary Water Pollution and Floods. Utrecht Law Rev. 2008, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leussen, W.; Van Slobbe, E.; Meiners, G. Transboundary governance and the problem of scale for the interpretation of the European Water Framework Directive at the Dutch-German border. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Adaptive & Integrated Water Management, CAIWA 2007, Basel, Switzerland, 12–15 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- van Rijswick, M.; Gilissen, H.K.; van Kempen, J. The Need for International and Regional Transboundary Cooperation in European River Basin Management as a Result of New Approaches in EC Water Law. ERA Forum 2010, 11, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Armitage, D.; De Loe, R.C.; Morris, M.; Edwards, T.W.; Gerlak, A.K.; Hall, R.I.; Huitema, D.; Ison, R.; Livingstone, D.; MacDonald, G.; et al. Science–Policy Processes for Transboundary Water Governance. Ambio 2015, 44, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstein, Y.; Eckstein, G.E. Transboundary Aquifers: Conceptual Models for Development of International Law. Ground Water 2005, 43, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.Y.; Peng, D.H. Consolidating SWOT Analysis with Nonhomogeneous Uncertain Preference Information. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2011, 24, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskidis, I.; Kokkos, N.; Sapounidis, A.; Triantafillidis, S.; Kamidis, N.; Koutrakis, E.; Sylaios, G.K. Ecohydraulic Modelling of Nestos River Delta under Low Flow Regimes. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2018, 18, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganoulis, J.; Kolokytha, E.; Mylopoulos, Y. Multicriterion Decision Analysis for conflict resolution in Transboundary River Basins. In Proceedings of the Integrated Water Management Of Transboundary Catchments: A Contribution From Transcat, Venice, Italy, 24–26 March 2004; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bournaski, E.; Ivanov, I.; Eleftheriadou, E.; Mylopoulos, Y. Towards Integrated Water Resources Management of the Mesta/Nestos Catchment by HEC-HMS modelling. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference BALWOIS, Montpellier, France, 23 and 26 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nakova, E.; Linnebank, F.E.; Bredeweg, B.; Salles, P.; Uzunov, Y. The River Mesta Case Study: A Qualitative Model of Dissolved Oxygen in Aquatic Ecosystems. Ecol. Inform. 2009, 4, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridou, D.; Michailidis, A.; Trigkas, M.; Stefanidis, P. Exploring Irrigation Water Issues Through Quantitative SWOT Analysis: The Case of Nestos River Basin. In Economic and Financial Challenges for Eastern Europe; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Law 2402/1996; The Bilateral Agreement between Greece and Bulgaria for the waters of Nestos River. Greek National Legislation: Athens, Greece, 1996.

- Martin, G. The European Water Framework Directive: An Approach to Integrated River Basin Management. In European Water Management Online; European Water Association (EWA): Munich, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachopoulou, M.; Coughlin, D.; Forrow, D.; Kirk, S.; Logan, P.; Voulvoulis, N. The potential of using the Ecosystem Approach in the implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 470–471, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulvoulis, N.; Arpon, K.D.; Giakoumis, T. The EU Water Framework Directive: From Great Expectations to Problems with Implementation. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).