1. Introduction

Water is a fundamental human right, probably one of the most important, precisely because its accessibility guarantees human dignity and freedom. Namely, it has been recognized by the international community. The need for water to meet basic human needs was first recognized worldwide in 1977 at the United Nations Conference on Water in Mar del Plata, Argentina, and was sealed on 28 July 2010 by Resolution 64/292 of the United Nations General Assembly. However, in January 1992, at the Dublin International Conference, one of the principles that were stated, inter alia, mentioned that “Water has economic value in all its competing uses and must be recognized as an economic good” [

1]. The return of its economic dimension, as a consequence of both its lack and the recognition of its special value (meant its subordination to the laws of the free market and that it can be distributed in such a way as to generate profit [

2]. All of the above, combined with the general prevalence of liberal policies, the lack of funds for further investments in infrastructure, and the weaknesses of the utilities have led to the privatization of water supply in many parts of the world. Nevertheless, this practice in most cases has failed due to the deterioration of its social dimension, resulting in the gradual remunicipalization of water services over the last decade around the world.

2. Materials and Methods

For this article, data were drawn from scientific articles on water supply, the European and Greek legislative decrees, the formal websites of Greek public and private organizations as well as global private organizations [

3]. Μost particularly, for the case of Greece, an analysis of the strengths weaknesses opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis of the existing water supply model was performed and combined with the analysis of various water supply practices that have been implemented worldwide and the future water supply model emerging regarding MWSSCs, which is the current dominant model of water supply services in the country.

3. Discussion

3.1. Privatization of Water Supply Cases

The privatization of water supply systems concerns the management transfer of ownership or services related to it to the private sector. This means transferring the whole water system ownership or even the sale of public rights to private companies as well as various combinations of all of the above [

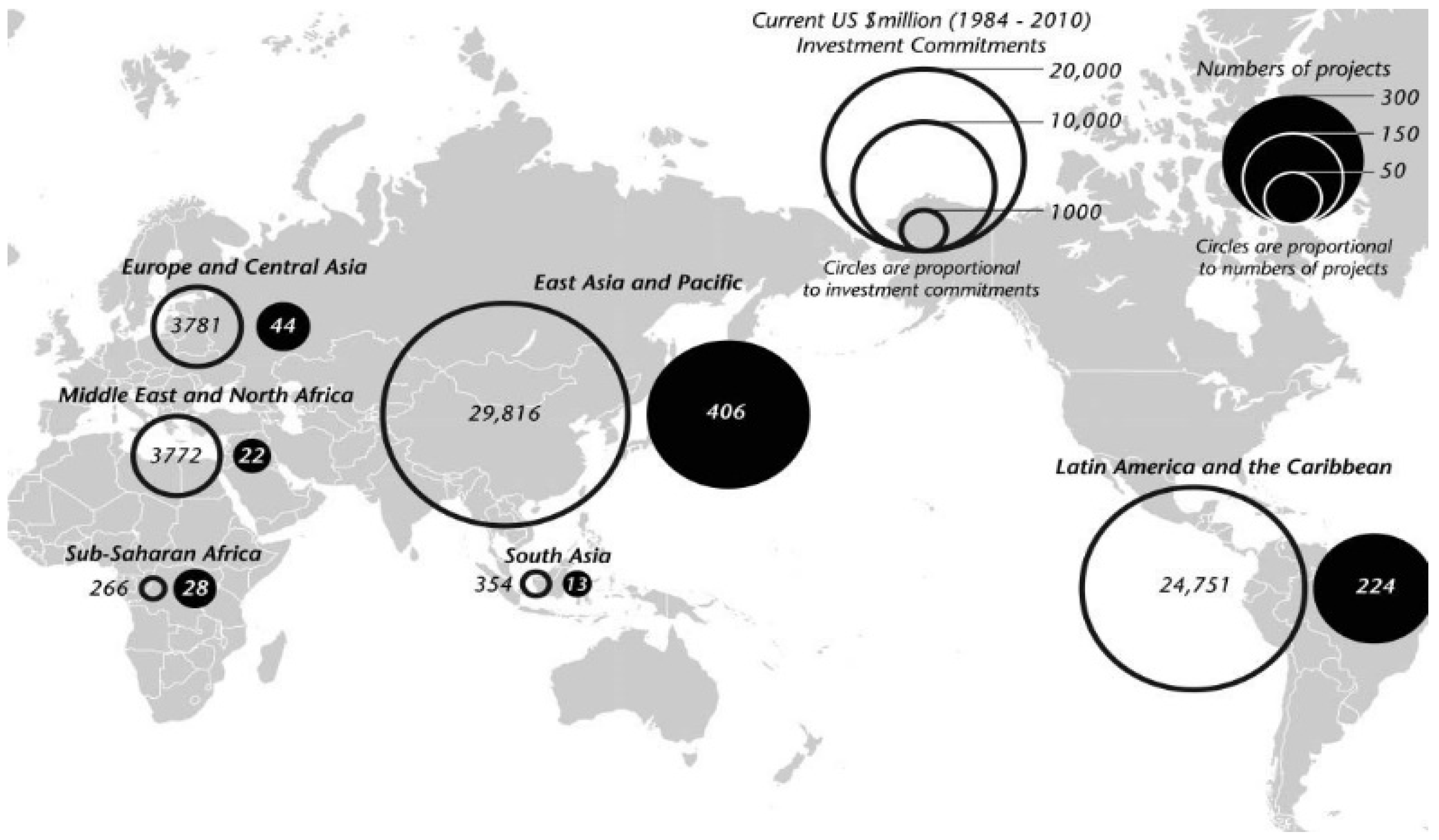

4]. The first water supply privatization attempt dates back to the early 20th century, due to many different reasons. Privatization in the water supply sector since almost 1980 has been significantly promoted by various international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WBG), which accelerated sharply during the 1990s, reaching a peak in 1997 for thereafter declining. Nevertheless, some water supply privatization practices have failed. The most notable cases, for instance, are those of Cochabamba in Argentina, Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, Manila in the Philippines, and Hamilton in Canada. The faults can be attributable to the extreme rise in water tariffs and the degradation in the water quality, but also to the non-implementation of planned and infrastructure projects. In contrast, there are cases such as in the municipalities of Finland, the city of Macau in China, and Bucharest in Romania where the implementation of privatization has had positive effects such as increased private connections, a reduction in the rates of non-revenue water, and stable water tariffs. The success of these cases also depends on the existence of an inviolable regulatory authority as well as strong political will (

Figure 1).

Other important reasons that allowed for the even greater spread of the privatization of water networks regards the constant lack of funds, the weakness of the public sector, and the degradation of existing water networks, either due to their age or due to their limited coverage. These phenomena have been adopted, especially in developing countries such as Asia, Africa, Latin America, and former Communist countries due to the strong pressure from international financial institutions. Nevertheless, it is also a common practice for developed countries such as Europe and North America due to the rise in neoliberal policies and the implementation of innovative technologies (

Table 1).

There are different forms of privatization around the world, which vary according to the degree of individual involvement in water management (

Table 2). As for the results of privatization, both socially and environmentally, they have been unfavorable in most areas where it was implemented due to key success factors such as social consensus. The acceptance and transparency in the procedures play a central role in contracts and amendments were absent. Furthermore, most cases were characterized by the delimitation of realistic goals and the lack of an independent regulatory authority. The main results were: (a) huge increases in water tariffs, especially for the poor; (b) deteriorating water quality; (c) monopolies; (d) corruption and a lack of transparency; and (e) a loss of know-how for the public sector. Particularly in developing countries that were already at a disadvantage in negotiating concessions due to poor financial conditions, the implementation of full recovery costs as a practice to maintain the profitability of private companies had disastrous consequences for the poor through the tragic rise in water prices, resulting in the collapse of the projects (Dar El Salaam, Cochabamba, Manila).

It should also be noted that in several cases such as in the cities of La Paz, El Alto, and Morocco, while the beginning of privatization had positive results, mainly in terms of increasing the network and private connection coverage, unfortunately, things gradually changed for the worst. The achievement of initially unrealistic goals that risked the interests of the private partners either led to the renegotiations of contracts or modifications of the initial terms in the interest of the private companies, or to the total breach of what was originally agreed, resulting in social reactions.

3.2. Remunicipalization of Water Suppliers-Cases

Remunicipalization of the water supply concerns the transition of water services from privatization in any of its various forms, to full public ownership, management, and democratic control [

6]. After more than three decades of the privatization of water suppliers, various cities around the world are re-undertaking water services under public management and ownership, with significant differences in the way that networks are financed and operated. The main reasons that led to the strengthening of this trend are listed in

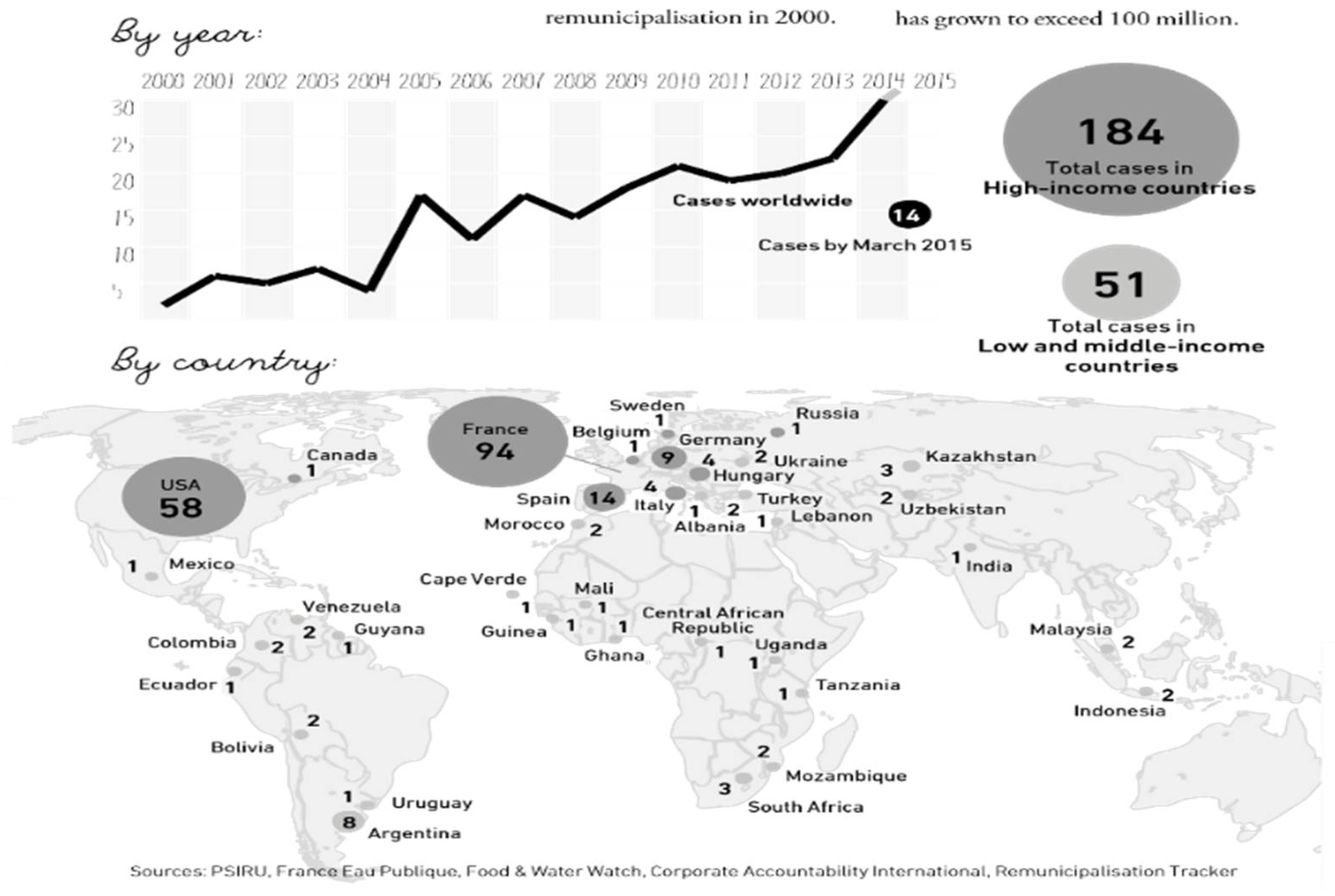

Table 3. Most cases of remunicipalization are observed in high-income countries, while the number of cases has almost doubled since 2009, which indicates the rapid acceleration of this phenomenon (

Figure 2), [

7]. The majority of remunicipalization cases have mainly taken place in two countries, France and USA, but it still has a global dimension with its appearance in almost every place that privatization has been previously implemented. Paris is the best-known example of water remunicipalization, as water services returned to the public sector in 2010, after almost 25 years of private management [

8]. The case of Uruguay is also indicative as it was the first country in the world to secure the right of access to water in its Constitution through a referendum [

9], after a brief experience with privatization in water utilities in the 1990s [

10].

The path to the remunicipalization of water supply is hard to study and analyze as it requires the exact point where privatization has failed and an understanding of the special characteristics of each area. On the other hand, in many cases, the recovery of water services by the public sector is very difficult because of the severe asset deficits left by many private companies such as reduced equipment and collapsing infrastructure. Conditions become significantly more difficult when a privatization contract is terminated before it is completed as this causes complex and tough political struggles, which often lead to unequal legal battles to the detriment of the public interest and social good. Despite the growing trend of the global remunicipalization of water utilities, there are significant forces that can slow it down or even reverse it such as tough opposition strategies from powerful private companies operating in the sector including legal challenges, inflated purchase prices, political pressures, politician bribery cases, and sabotage of systems/infrastructure [

11].

3.3. The Role of PPPs in Water Supply

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) involve cooperation between the public and private sectors for the financing, construction, renovation, management, and maintenance of public infrastructure. In other words, to provide services in sectors of the national economy where market liberalization is either impossible or undesirable. The main reasons for why the public sector turns to a PPP contract are [

12]: (a) a lack of funds or a change to other priorities; (b) the private actor can offer the same service at a lower price or bring a better result at the same cost; and (c) the private actor is a better risk manager.

There are various forms of PPPs in the water sector, designed either to address the main problems of water supply network development or to improve the operational, economic, and environmental efficiency of the existing water utilities (

Table 4). However, the case of water supply is special because of its necessity for human survival, which makes it a natural monopoly. For this reason, special attention should be paid to the implementation parameters of PPPs such as the recognition of the special role of each partner, social acceptance, the guarantee of transparency, and meritocracy in the contracting procedure. This means the presence of regular performance appraisal and the existence of a strong regulatory authority [

4]. The application of PPPs when the above-mentioned conditions are met can solve significant problems in the provision of water services, mainly due to the lack of financial capital but also because of the lack of know-how from the public sector. However, their selection by governments should not be a panacea, as well-thought-out actions are required to ensure their success due to their complexity and high cost.

3.4. Performance-Based Service Contracts (PBSCs)

Performance-based service contracts (PBSCs) are a flexible approach where a private company is called upon to implement a specific program, paid for services, and appropriate incentives to meet the business performance measures [

14]. Under such a program, a favorable environment prevails, and incentives are given to address specific problems, with immediate operational and financial benefits when a proper balance is struck between management oversight and private partner initiatives. However, such service contracts are not substitutes for broader and necessary institutional reforms to promote the sustainability of the water sector. The issues that can be addressed through them are mainly operational problems such as the reduction in the percentage of non-revenue water as well as problems or errors that occur during the billing process (collecting bills, metering), etc.

3.5. The Special Case of Greece

In Greece, the public sector is responsible for water management, which is mainly directed by municipal water supply and sewerage companies (MWSSCs) or by water utilities of various municipalities (which cover 40% and 5% of the population of the country respectively). In the two major metropolitan areas centers (Athens and Thessaloniki), the provision and management is conducted by the Water Supply and Sewerage Company of the Capital (EYDAP SA) and the Water Supply and Sewerage Company of Thessaloniki (EYATH SA). The State represents the main stakeholder and covers a total of 55% of the national population. Other water suppliers in the country are the Water Supply Association of Ioannina Basin (S.Y.D.L.I) in Ioannina as well as the Development Organization in Crete (O.A.K. A.E.). Both organizations supervise the operation and maintenance of large hydraulic projects such as dams, reservoirs, and water treatment plants and they provide the local MWSSCs with water, which manage the water supply networks. A quite similar condition is met in Cyprus, where the control of water resources and the water supply system is the main responsibility of the Department of Water Development of the Ministry of Agriculture and the network of cities and the local water supply councils. The case of Greece in the field of water supply is special. On one hand, it is like other European countries such as France where the water supply is under the supervision of large public bodies and organizations in big cities and is under the control of municipal companies such as MWSSCs in smaller settlements. On the other hand, in Europe, private participation in the water sector in various forms of PPPs is particularly common, in Greece and especially in MWSSCs is very limited, almost exclusively in the field of outsourcing. At the same time, Greece presents the peculiarity of having two main similarities with the developing countries of Africa and Latin America as well as EU former communist countries, who accepted the private sector’s participation in water utilities:

- -

Receives overwhelming pressure from international financial institutions to allow privatization including the water sector due to financial agreements that have concluded for financial further support;

- -

A large percentage of outdated water networks is observed, mainly in the provinces and small settlements where significant funds are necessary and the public sector cannot afford upgrades of the existing infrastructure.

Based on the above analysis, the water supply sector in the country is particularly vulnerable on the part of MWSSCs, as most of the weaknesses in their operation and the biggest threats are located there. In the field of financing, the two major water suppliers EYDAP and EYATH have already proceeded to the implementation of PPPs in order to cover the increased required funds for the construction of new water supply infrastructure. However, the smaller water utilities (MWSSCs) are mainly supported by European financing programs such as the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF), etc. and proceed only to outsourcing contracts for the construction of projects or the provision of services. Infrastructure management contracts have been concluded between MWSSCs and private partners mainly in the operation of sewage treatment plants.

The public nature of water in Greece is strongly supported by citizens, organizations, and institutions, although there are several vulnerabilities such as the financial situation of the utilities, especially in MWSSCs and in the water services of municipal authorities. The main reason is that the existing model protects the social character of water by ensuring accessibility to it by all social groups. This is clearly proven by the fact that the efforts to date of the privatization of the two largest national water providers, EYDAP SA and EYATH SA, found strong resistance from Greek society, which was reflected in the relevant recent judicial decisions. However, the main challenges for the future are: (a) the reduction in non-revenue water rates, which in the case of local utilities is high enough, in order to protect the water resource but also to ensure the viability of the facilities; (b) the construction, operation, and maintenance of large projects like water treatment plants; (c) the replacement of old pipelines and network extensions; and (d) the full implementation of new technologies (GIS, telemetry, etc.). All of the above require the implementation of the appropriate water supply model in the future, considering the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the current situation in Greece (

Table 5).

3.6. Proposed Water Supply Model in Greece-MWSSCs

Based on the examples above, the full assignment of water services to the private sector is unquestionably doomed to fail as the character of water as a social good is clearly undermined. Therefore, maintaining the status quo without any further contribution from the private sector apart from outsourcing does not significantly improve the current situation. The main reason is that there is always a need to build large infrastructure projects that require new funds. European/national/regional funding programs are considered to be solutions to this problem. However, they do not always represent the solution because network maintenance and extensions are also ongoing, and if external financial support may possibly be reduced in the future, the existing model would collapse. The above leads to the solution for concluding a PPP contract for water utilities to benefit from the private funds but also from the transfer of know-how, and this should be recognized as a preventive action and not as a pretext for the sale of public property. However, for such a model to be acceptable in general, special emphasis must be given to the success factors analyzed above. In particular, the model of PBSC is judged as the most appropriate type of PPPs. Given their short duration, the public sector and MWSSCs are not alienated from know-how in long-term forms such as concessions. Therefore, the possibility of continuous renewal and consequent adjustment to the contract terms is provided. This model in the field of water supply has successfully been applied abroad in the field of the reduction in non-revenue water, which is the main weakness of MWSSCs. Regarding the private partner, which takes on the financial risk of the project, the profits are determined from the beginning based on their efficiency while the physical object of the contract is clearly defined.

4. Conclusions

The privatization of water supply mainly started in developed countries as a product of neoliberal policies and is due to a significant lack of funds and weaknesses of public utilities in such countries. In the vast majority of cases, with the gradual transition of water services back to public sector, it has failed. However, the municipalization of water is not an easy process as it requires proper preparation and an appropriate institutional framework, know-how, reorganization of the operation of the utilities, and new funds for investment. However, the contribution of the private sector is necessary to improve water services. The exact model, the degree of participation, and the special characteristics of each PPP contract determine the success of the cooperation between the public and private sector. In the case of water supply, the responsibility of the state to ensure the social good is even more crucial given its irreplaceable value. A special challenge for Greece, and more specifically for MWSSCs, which are classified as the most “problematic” of water utilities, is to take the maximum advantage of the contribution of the private sector to improve their efficiency, achieve further savings of water resources, but also ensure their economic sustainability in the future. Even though Greek society is opposed to privatization, especially in the water sector, the implementation of PBSCs should be seriously considered. This is considered necessary to deal with the large percentage of non-revenue water, which is the main source of financial losses and water resources waste.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, V.K. and A.K.; Investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; Writing-review and editing, V.K., Supervision, V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: [

3].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Savenije, H.; Van Der Zaag, P. Water as an Economic Good and Demand Management Paradigms with Pitfalls. Water Int. 2002, 27, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; South, N.; Walters, R. The commodification and exploitation of fresh water: Property, human rights and green criminology. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2016, 44, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumpli, A. Privatization or Remunicipalization of Water Supply: Good and Bad Practices and the Case of Greece. Masters’s Thesis, Greek Open University, Patras, Greece, 2021. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, P.; Wolff, G.; Chalecki, E.; Reyes, R. The New Economy of Water: The Risks and Benefits of Globalization and Privatization of Fresh Water; Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment, and Security: Oakland, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K. Neoliberal Versus Postneoliberal Water: Geographies of Privatization and Resistance. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakoudis, V.; Tsitsifli, S. Doing the urban water supply job: From privatization to remunicipalisation and the third pillar of the Performance Based Service Contracts. Water Util. 2014, 8, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto, S.; Lobina, E.; Petitjean, O. Our Public Water Future: The Global Experience with Remunicipalisation, TNI, PSIRU, Multinationals Observatory; Queen’s University: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2015; pp. 1–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Lobina, E.; Terhorst, P. Re-municipalisation in the early twenty-first century: Water in France and energy in Germany. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2013, 27, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshman, R. The constitutional Right to Water in Uruguay. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 2005, 5, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Spronk, S. Alternatives to the Privatisation of Water and Sanitation Services: Lessons from Latin America. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Development; Grugel, J., Hammett, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, D. Will the empire strike back? Powerbrokers and remunicipalisation in the water sector. Water Altern. 2019, 12, 348–359. [Google Scholar]

- Kanakoudis, V.; Tsitsifli, S. Urban water services public infrastructure projects: Turning the high level of the NRW into an attractive financing opportunity using the PBSC tool. Desal Water Treat. 2012, 39, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, S.; Frone, D. Issues of Efficiency for Public-Private Partnerships in the Water Sector. Stud. Sci. Res. Econ. Ed. 2018, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsifli, S.; Kanakoudis, V. Public vs. Private Water Utilities: PBSCs and PPPs used for financial sustainability. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference Environmental Management, Planning & Engineering (CEMEPE), Mykonos, Greece, 21–26 June 2009; Volume I, pp. 453–458. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).