Clean Water and Sanitation for All: Study on SDGs 6.1 and 6.2 Targets with State Policies and Interventions in Nigeria †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Clean Water and Sanitation for All and the Sustainable Development Goals

2.1. Target 6.1

By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all.(Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform, 2015)

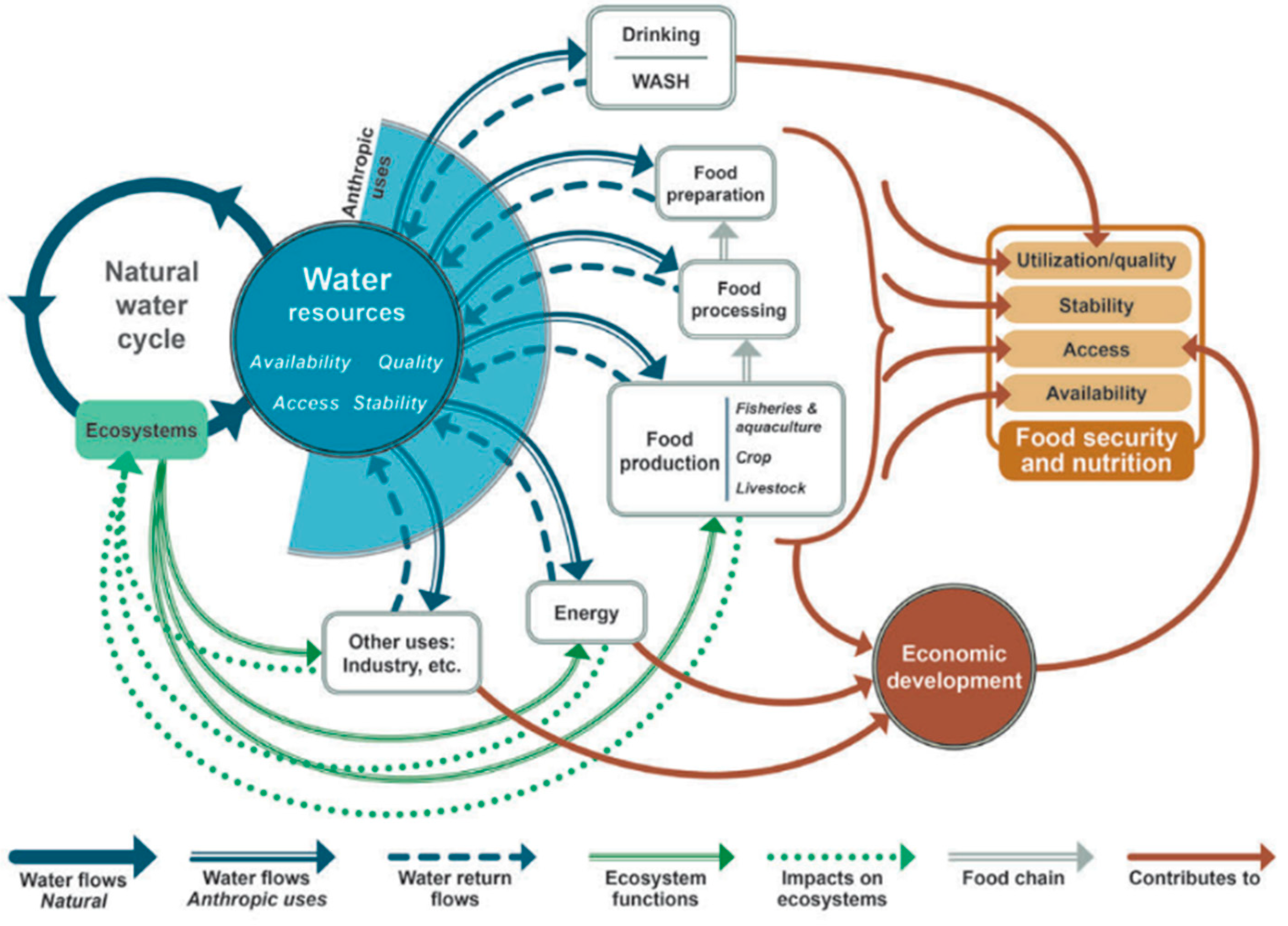

2.2. Universal Access to Water and Zero Hunger

By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving by 2025 the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and older persons.(Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform, 2015)

2.3. Universal Access to Water through Infrastructure

Develop a quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all.(Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform, 2015)

3. Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, Gender and the Sustainable Development Goals

3.1. Target 6.2

By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations.(Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform, 2015)

3.2. Access to Safe and Affordable Drinking Water and Fighting Waterborne Diseases

By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases.(Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform, 2015)

3.3. Women and Girls and Their Right to Gender Equality and Water Accessibility

Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate.(Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform, 2015)

4. Nigeria’s Progress towards Implementing SDG 6.1 and 6.2

4.1. WASH Policies in Nigeria

4.2. Government

4.3. International Organizations

5. Challenges towards Achieving WASH

5.1. Poverty

5.2. Lack of Infrastructure

5.3. Misgovernance

5.4. Lack of Proper Data

5.5. Climate Change

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations

- (a)

- Governments at all levels need to work with the key stakeholders in WASH to improve the local water governance.

- (b)

- There is the need to reinforce the capacity of the local and national authorities to manage and control sanitation systems, including the improvement of data management frameworks.

- (c)

- Rank water efficiency as very important across activities by introducing the best practice technologies for water preservation in regions where the water is insufficient.

- (d)

- Guarantee that the voices of women and girls, who the most affected by the lack of WASH services, are acknowledged in water and sanitation plans of action.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. World Bank: Overview Nigeria. World Bank. (3 November 2020). Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/overview (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Adelakun, O.J. Human Capital Development and Economic Growth in Nigeria. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Inabo, O.A.; Arshed, N. Impact of health, water and sanitation as key drivers of economic progress in Nigeria. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Inno. Dev. 2019, 11, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2014. United Nations Children’s Fund, New York. Available online: http://www.unicef.org/statistics/index_24302.html (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Akoteyon, I.S. Inequalities in access to water and sanitation in rural settlements in parts of southwest Nigeria. Ghana J. Geogr. 2019, 11, 158–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nwankwoala, H.O. Localizing the strategy for achieving rural water supply and sanitation in Nigeria. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 5, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeta, M. Rural water supply in Nigeria: Policy gaps and future directions. Water Policy 2018, 20, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTI International. Effective Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Services in Nigeria (E-WASH). Available online: https://www.rti.org/impact/effective-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-services-nigeria-e-wash (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Alao, A.; Garrett, J. How Can Nigeria Fill the Funding Gap to Address Its State of WASH Emergency? WASH Matters. (20 December 2021). Available online: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/blog/how-can-nigeria-fill-the-funding-gap-to-address-its-state-of-wash-emergency (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Akpabio, E.M. Water Supply and Sanitation Services Sector in Nigeria: The Policy Trend and Practice Constraints; ZEF Working Paper Series, No. 96; University of Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF): Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gbadegesin, A.S.; Olorunfemi, F.B. Changing trends in water policy formulation in Nigeria: Implications for sustainable water supply provision and Management. J. Sust. Dev. Afr. 2009, 1, 266–285. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation: 2012 Update. World Health Organization. 2012. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44842 (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Bayu, T.; Kim, H.; Oki, T. Water Governance Contribution to Water and Sanitation Access Equality in Developing Countries. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR025330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hope, R.; Thomson, P.; Koehler, J.; Foster, T. Rethinking the economics of rural water in Africa. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO/UNICEF. Ending Inequalities: A Cornerstone of the Post 2015 Development Agenda, 2015. Available online: https://www.wssinfo.org/leadmin/user_upload/resources/JMPfactsheet2ppWEBinequalities.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Choufani, J.; Ringler, C. The SDGs on Zero Hunger and Clean Water and Sanitation Can’t Be Achieved without Each Other, So Where Do We Start? (2016, November) ifpri.org. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/sdgs-zero-hunger-and-clean-water-and-sanitation-cant-be-achieved-without-each-other-so-where-do (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Ringler, C.; Choufani, J.; Chase, C.; McCartney, M.; Mateo-Sagasta, J.; Mekonnen, D.; Dickens, C. Meeting the Nutrition and Water Targets of the Sustainable Development Goals: Achieving Progress through Linked Interventions 2018; (WLE Research for Development (R4D) Learning Series 7); CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2018; 24p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Matemilola, S. The challenges of food security in Nigeria. Open Access Libr. J. 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, S.; Adshead, D.; Fay, M.; Hallegatte, S.; Harvey, M.; Meller, H.; O’Regan, N.; Rozenberg, J.; Watkins, G.; Hall, J. Infrastructure for sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovsky, L.; Augsburg, B.; Lührmann, M.; Oteiza, F.; Rud, J.P.; Smith, K. Sanitation: Saving Lives in Developing Countries. WASH Matters. May 2019. Available online: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/blog/sanitation-saving-lives-in-developing-countries (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Okuku, M.O. Policy Brief: Ending Open Defecation in Nigeria. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health 2020, 41, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water and Sanitation Program Nigeria. Economic Impacts of Poor Sanitation in Africa: Nigeria Loses NGN455 Billion Annually Due to Poor Sanitation 2012. WSP. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/855961468297356898/pdf/681260WSP0ESI0000Box367907B0PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Emenike, C.P.; Tenebe, I.T.; Omole, D.O.; Ngene, B.U.; Oniemayin, B.I.; Maxwell, O.; Onoka, B.I. Accessing safe drinking water in sub-Saharan Africa: Issues and challenges in South–West Nigeria. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 30, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumwenda, S. Challenges to hygiene improvement in developing countries. IntechOpen 2019, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Matto, M.; Singhal, S.; COVID-19 and SDG 6 Goals: All That We Need to Learn and Do. Down to Earth. 2020. Available online: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/environment/covid-19-and-sdg-6-goals-all-that-we-need-to-learn-and-do-71314 (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Oxfam. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals 5 and 6: The Case for Gender-Transformative Water Programmes—World. ReliefWeb. March 2020. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/achieving-sustainable-development-goals-5-and-6-case-gender-transformative-water (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Kayser, G.L.; Rao, N.; Jose, R.; Raj, A. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: Measuring Gender Equality and Empowerment. World Health Organization. 3 June 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/97/6/18-223305/en/#:~:text=Women%20and%20girls%20are%20disproportionately,infection%20around%20menstruation%20and%20reproduction (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Akpabio, E.M.; Wilson, N.A.U.; Essien, K.A.; Ansa, I.E.; Odum, P.N. Slums, women and sanitary living in South-South Nigeria. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 1229–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adesogan, S. Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals 6.1 and 6.2 in rural small communities of Ondo State, Nigeria. J. Glob. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 8, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- United States Agency for International Development. Water and Development Country Plan for Nigeria. 2015. Available online: https://www.globalwaters.org/sites/default/files/Nigeria%20Country%20Plan%20final.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Root, R. Q&A: Nigeria Is Finally Getting Serious about WASH. Devex. 17 January 2020. Available online: https://www.devex.com/news/q-a-nigeria-is-finally-getting-serious-about-wash-96344 (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- United Nations. Poverty Eradication. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/socialperspectiveondevelopment/issues/poverty-eradication.html#:~:text=Poverty%20entails%20more%20than%20the,of%20participation%20in%20decision%2Dmaking (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- United Nations Global Settlements Programme (UNGSP). The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements. 2003, p. xxvi, ISBN 978-1-84407-037-4. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/the-challenge-of-slums-global-report-on-human-settlements-2003 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Bloomfield, S.F.; Nath, K.J. Use of Ash and Mud for Handwashing in Low-Income Communities International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene (IFH); International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene: Somerset, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo, E.; Galiani, S.; Mobarak, M. Improving Access to Urban Services for the Poor: Open Issues and a Framework for a Future Research Agenda. (October 2012); Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R.C.; Tyrrel, S.F.; Howsam, P. The Impact and Sustainability of Community Water Supply and Sanitation Programmes in Developing Countries. Water Environ. J. 1999, 13, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheingans, C.; Moe, C.L. Global Challenges in water, sanitation and health. J. Water Health 2006, 4 (Suppl. 1), 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 6: Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation. New York. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/sdg-6-synthesis-report-2018-on-water-and-sanitation/ (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- WHO/UNICEF. Joint Monitoring Programme. Home | JMP. 2021. Available online: https://washdata.org/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Africa Water Week. Inclusive Urban WASH Services under Climate Change; Future Climate for Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018; Available online: https://futureclimateafrica.org/news/africa-water-week-2018-inclusive-urban-wash-services-under-climate-change/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Jones, N.; Bouzid, M.; Few, R.; Hunter, P.; Lake, I. Water, sanitation and hygiene risk factors for the transmission of cholera in a changing climate: Using a systematic review to develop a causal process diagram. J. Water Health 2020, 18, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shehu, B.; Nazim, F. Clean Water and Sanitation for All: Study on SDGs 6.1 and 6.2 Targets with State Policies and Interventions in Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 15, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022015071

Shehu B, Nazim F. Clean Water and Sanitation for All: Study on SDGs 6.1 and 6.2 Targets with State Policies and Interventions in Nigeria. Environmental Sciences Proceedings. 2022; 15(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022015071

Chicago/Turabian StyleShehu, Bala, and Fibha Nazim. 2022. "Clean Water and Sanitation for All: Study on SDGs 6.1 and 6.2 Targets with State Policies and Interventions in Nigeria" Environmental Sciences Proceedings 15, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022015071

APA StyleShehu, B., & Nazim, F. (2022). Clean Water and Sanitation for All: Study on SDGs 6.1 and 6.2 Targets with State Policies and Interventions in Nigeria. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 15(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022015071