Abstract

This article draws heavily on my PhD thesis (as the last reference), which was published after the ICSD 2021 conference took place. The study investigates how local traditional knowledges are informing Indigenous women entrepreneurs (IWE) in promoting sustainable economic development in their communities during the 2020–2021 Covid-19 pandemic. The research is grounded in Indigenous guided participatory approaches with collaborators/participants from six Tseltal communities located in Chiapas, Mexico. The research findings offer deep immersion into the critical aspects of Tseltal knowledge, including environmental, social, cultural, and economic dimensions. These aspects leverage local capacity in developing sHachel jwohc’ a’tel (Tseltal entrepreneurship initiatives) while enabling opportunities for gender transformative collaborative work and sna’el ya’beyel stuc te bin ay ma’yuc (Tseltal economic development grounded in community wellbeing).

1. Introduction

The term Indigenous Entrepreneurship is relatively new in scholarship even though Indigenous Peoples have pursued what is understood as “entrepreneurial initiatives” for hundreds of years. The concept “entrepreneurship” has been documented across multiple disciplines since the 1800s and its mainstream terms and definitions usually include aspects of decision-making and management in terms of resources, opportunities, value generation, and success assessment []. However, the understanding of common concepts such as “resource”, “wealth”, “value”, and “success” may drastically differ depending on the local context, especially if the context is Indigenous. Entrepreneurship is heavily influenced by entrepreneurs’ culture, it “should not be defined on the basis of opportunity, but rather cultural perception of opportunity” [] (p. 3). Indigenous peoples have distinct cultures and knowledges, so it is possible to assume that there are as many definitions of Indigenous entrepreneurship as Indigenous communities currently pursuing entrepreneurial initiatives. Recent studies on the topic have identified a few points of alignment among Indigenous entrepreneurship’s initiatives, such as the inclusion of non-economic explanatory variables, environmentally sustainable practices based on traditional ecological knowledges (TEK), and governance structures based on kinship ties []. Based on these points of alignment, many definitions have emerged highlighting core characteristics such as the fact that the creation, management, and development of such ventures are undertaken by Indigenous people for the benefit of Indigenous people. Indigenous entrepreneurship initiatives can pertain to either the private, public, or non-profit sectors generating a broad range of desired benefits, from economic profit for a single individual to the broad view of multiple social and economic advantages for entire communities and their stakeholders [] (p. 132).

An essential aspect in constructing the definition of Indigenous entrepreneurship across scholarship is that several authors agree that it critically involves the participation of Indigenous peoples, the ways they see the world, and their distinct knowledges []. However, even though Indigenous knowledges (IK) and worldviews have a critical role in this field, their relevance has not been systematically investigated []. This gap in scholarship can be due to the difficulty of conducting research and writing about IK using Western methodologies and colonial languages. The meaning and understanding of Indigenous concepts can drastically change when interpreted by non-Indigenous peoples []. In the face of this, many Indigenous authors have explored common characteristics across Indigenous cultures and explain that they share a few grounding principles: traditional knowledges that are holistic, cyclic, and connected to everything; acknowledgement of many truths that are dependent upon individual experiences; understanding that everything is alive and that all things are equal; the sacredness of their lands; and the importance of their relationship with the spiritual world, among others []. In the context of Indigenous development and entrepreneurship, Peredo and McLean identify three universal characteristics of Indigenous cultures: collective or communal orientation, inclination to a kin-based social structure, and their preference to consider social and cultural aims as being at least equally as important as material gains [] (p. 605).

Understanding the value of relationality from Indigenous perspectives can be helpful in studying how Indigenous peoples transform and adapt the practice of entrepreneurship by providing utmost equal importance to land, community, and relations (both social and spiritual) with all beings. In fact, some authors argue that relationality (interpreted as embeddedness) “can be a motivator that triggers entrepreneurship” [] (p. 2). This suggests that in investigating topics related to Indigenous entrepreneurship, researchers must be prepared to observe complex terms and practices in which meanings adjust and change depending on the locations, values, traditions, and histories of the specific entrepreneurial ventures studied. Since these ventures are heavily influenced by Indigenous worldviews—which are distinctive, fluid, and holistic—the methodologies used to conduct studies in this field must align with these characteristics. In addition, researchers are encouraged to acknowledge that, in translating practice to written theory in colonial formats, layers of complexity are likely to be omitted. This study integrates these methodological aspects and aims to understand how the participant Indigenous communities undertake sustainable development projects through the work of Tseltal women in their entrepreneurial initiatives. It was undertaken with the participant communities to collaboratively document and analyze the constructs of their local knowledges and practices in addressing the economic challenges of their communities. The results can potentially contribute to finding points of alignment between Indigenous knowledges and Western approaches to sustainable development that advocate for increasing community wellbeing along social, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions.

2. The Study Context and Methodology

This study was undertaken in the Municipalities of Ocosingo and Chilón, in Chiapas, Mexico. In this territory, 80% of the population identify as Tseltal, one of the main Maya cultures of this region []. Among many of the Maya contributions to the advanced understanding of math, linguistics, astronomy, and philosophy are the concept of the number zero, the most sophisticated system of writing of their time combining ideograms and phonograms, complex studies and calculations used to accurately predict the movement of the planets and stars, architecture innovations such as domes, arches, and wide interior spaces, and sophisticated governance models [,,,]. One of their most popular works is the Popol Wuj, which reveals “the K’iche’ authors’ sagacity and creativity in their struggle to defend the memories, knowledge, and values of their people tenaciously” [] (p. 3).

Until this day, many Maya peoples keep tirelessly contributing to the assertion of their culture and keep resisting and defending their autonomy in a context that has historically ranked in the last position in the Human Development Index for the last hundred years []. According to the last poverty report by the National Council of Social Development Policy Evaluation, 94% of the population of Chiapas lives in a situation of vulnerability, poverty, or extreme poverty []. Recent studies have revealed that one of the main reasons for the current state of vulnerability in Chiapas is the increasing rates of food insecurity related to sociodemographic characteristics and low-income factors [,]. This situation refers mainly to the drastic decrease in the production of food for self-consumption which has impacted the economic income of Indigenous families, allowing the penetration of cheap industrialized foods with high fat and carbohydrate content []. The situation is directly contributing to the progressive abandonment of traditional healthy practices, such as the preparation of handmade tortillas and the cultivation of local greens and vegetables, among other local foods. Currently, Chiapas is the largest consumer of beverages and soft drinks with high sugar content, which mainly affects Indigenous children, youth, and the elderly population by increasing their risk of suffering morbid obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases []. In the face of the pandemic caused by COVID-19 during 2020, the level of risk of the Indigenous communities in this territory increased due to the lack of access to health services, clean water, and sanitary products.

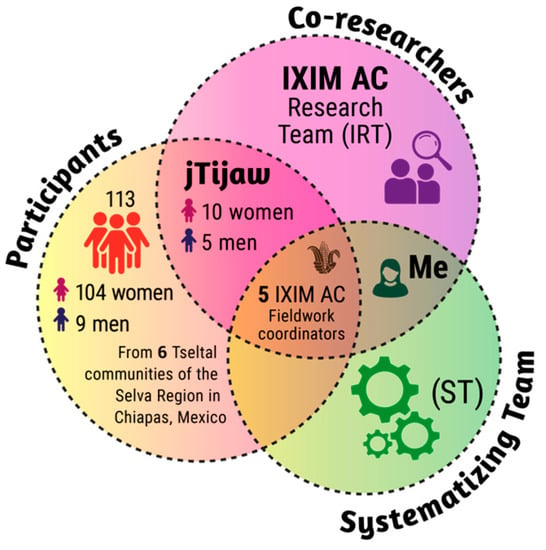

The associated nonprofit organization of this research study, IXIM AC, is one of several organizations and initiatives in this region that are focused on addressing issues of malnutrition and food security. Currently, a network of 15 Tseltal communities’ representatives, collaborating with IXIM AC’s team and stakeholders (such as fieldwork coordinators, nutritionists, agricultural specialists, engineers, academic researchers, and committed individuals from funding agencies and other NGOs), coordinate efforts in promoting local entrepreneurial projects. The communities’ representatives, traditionally called jTijaw, are Tseltal women that are community promoters, organizers, and leaders working as volunteers by popular demand in their communities. The jTijaw, their groups, and IXIM AC’s fieldwork coordinators are the 133 participants that are collaborators and co-researchers in this study.

The research was designed and undertaken using a unique participative approach grounded in the collaborators/participants’ practices, perspectives, and knowledges. The collaborators/participants guided and collaborated in all the research activities using interchangeable roles, from planning the research, including its scope and design from June 2018 to March 2020, to data gathering, analysis, results systematization, and knowledge mobilization from April 2020 to March 2021. By incorporating values and methods from community-based participatory research (CBPR) [], Fals Borda’s approach for participatory action research (PAR) [,,], insurgent research principles [], and Indigenous grounded theory (IGT) [,], the data were gathered and analyzed by the collaborators/participants through traditional orally based processes of collective knowledge creation in the shape of collaborative workshops in their communities led by the jTijaw and organized by IXIM AC’s fieldwork coordinators. The participants’ interchangeable roles are described as follows:

- 128 participants: 113 Tseltal people organized in six groups led by 15 community promoters or jTijaw.

- 20 participants and co-researchers: 15 jTijaw and 5 IXIM AC fieldwork coordinators. According to their roles in this study, these 20 people are organized into two teams:

- The IXIM AC research team (IRT), comprised of 21 participants including the 15 jTijaw, the 5 IXIM AC fieldwork coordinators, and the author of this paper (Me in Figure 1) as lead co-researcher. The 15 jTijaw were participants but also performed duties of data gathering through voice recordings, language translation, and IK interpretation distinctive for each of their communities for this research. At the same time, their work as participants was documented in voice recordings by the five IXIM AC fieldwork coordinators.

Figure 1. Participants and co-researchers.

Figure 1. Participants and co-researchers. - The systematizing team (ST): composed of six people including the five IXIM AC fieldwork coordinators and the author of this paper as lead co-researcher. The five IXIM AC fieldwork coordinators are considered participants of this study because their perspectives and experiences working with the jTijaw and their groups in the six Tseltal communities were considered as part of the data. However, they also collaborated in the gathering, cultural and language translation, coding, and analysis of the data using traditional orally based methods following the IGT methodology [,].

An explanatory graphic of the interchangeable roles of the participants and co-researchers is presented in Figure 1.

Among the findings from this research, it was identified that this study’s unique methods used in the collaborative workshops and grounded in orally based practices integrate core elements of Indigenous research methodologies that are grounded in the commitment to empower the participants to address their communities’ needs [].

3. Results

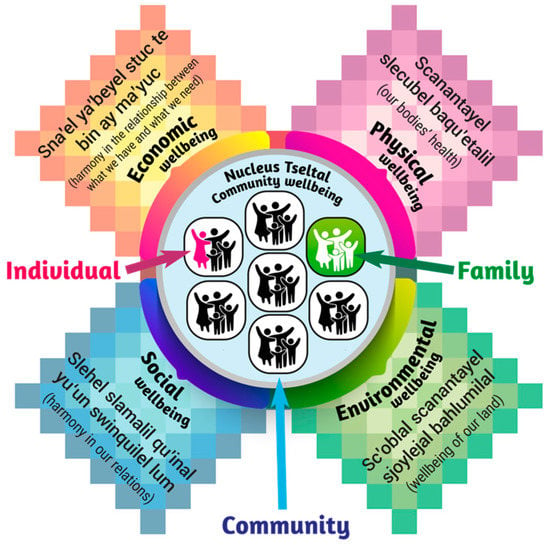

The co-creators/participants of this research perceive that for Tseltal community wellbeing or buhts’an qu’inal to exist, it is essential to attend to the holistic, all-encompassing wellbeing of all the community’s individuals. Each Tseltal individual’s wellbeing transcends to the wellbeing of their families that create and generate their sense of community. The participants/collaborators of this study identify this three-dimensional interconnection between the individual–family–community as the Nucleus of Tseltal community wellbeing, which is at the center of what the participants/collaborators call the four building elements of buhts’an qu’inal (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Nucleus of Tseltal community wellbeing.

The three interconnected components of the Nucleus of Tseltal community wellbeing are the Tseltal individual, the Tseltal family, and the Tseltal community. As illustrated in Figure 2, these components are dependent on each other. The Four Elements of buhts’an qu’inal are Scanantayel slecubel baqu’etalil (our bodies’ health), Slehel slamalil qu’inal yu’un swinquilel lum (harmony in our relations), Sc’oblal scanantayel sjoylejal bahlumilal (wellbeing of our land), and Sna’el ya’beyel stuc te bin ay ma’yuc (the harmony in the relationship between what we have and what we need). During the data analysis, the ST identified additional aspects that provide a better understanding of how these four elements are interconnected to each other.

Based on these findings, Buhts’an qu’inal can be translated into English as the physical and emotional state of savoring life in harmony with the surrounding community, which includes the natural environment. It is a temporary state of body and mind with deep communal components, and its meaning can be interpreted in multiple ways because the expression works as a metaphor, adapting to each Tseltal individual, family, and community’s conception of how experiencing a “delicious” moment feels.

Each of the Four Elements of buhts’an qu’inal can be examined and explained from each of their components, meanings, and indicators, but this endeavor is beyond the purposes of this article. The results of the research show the multiple dimensions in which Tseltal knowledge and practices are grounding the work of Tseltal women entrepreneurs in the six participant communities. They offer deep immersion in Tseltal ontology and epistemology and show how the collaborators/participants of this research are leveraging their traditional practices and ways of understanding life to promote their communities’ wellbeing.

Tseltal knowledge and practices are rich and complex; it would be impossible to observe, study, and interpret their depth and reach all their dimensions in one research study. For the purposes of this research, the collaborators/participants focused on studying the element of Sna’el ya’beyel stuc te bin ay ma’yuc (the harmony in the relationship between what we have and what we need) or the Tseltal understanding of community economic wellbeing. The collaborators/participants of this study identified that one way in which the results can be interpreted and discussed for academic purposes is by taking the main indicator of success for their entrepreneurial initiatives and systematizing it in the form of four aspects that were identified as critical in their endeavors.

The results show that the main indicator of success in the development of sHachel jwohc’ a’tel (Tseltal initiatives of entrepreneurship) is the sustained engagement of the women Indigenous entrepreneurs in the collaborative work oriented to Sna’el ya’beyel stuc te bin ay ma’yuc (the harmony in the relationship between what we have and what we need) or community economic wellbeing. The elements of this sustained engagement were systematized into four aspects that were identified as critical in guiding and defining the collaborative efforts in developing sHachel jwohc’ a’tel (Tseltal initiatives of entrepreneurship): 1. Consistency in the relationships, 2. Knowledge of the local culture and traditions, and experience in working in the local communities, 3. Fluency in the local ways of communication and language, and 4. Grounding the work in related local practices.

The discussion of these four aspects is oriented to offer a glance at the different ways in which Tseltal entrepreneurs, especially Tseltal women, are designing and leading innovative ways to promote the economic wellbeing of their communities through collaborative entrepreneurship initiatives while remaining deeply grounded in their traditional knowledge, roles, and practices. In this study, the results show that for Indigenous entrepreneurs, their traditional knowledges offer them a reliable framework that outlines effective protocols for capacity building, stakeholder engagement, and collaboration. Specifically, in the case of the participant Indigenous women entrepreneurs, their Tseltal knowledge and practices are sources of creativity and innovation that are constantly supporting them in overcoming challenges and opening up new pathways and opportunities for social change and community thriving.

4. Discussion

Social capital can be defined as “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition” [] (p. 248). In the case of social innovation, social capital works as networks of relationships among the local community that enable certain resources or processes to take place, often resulting in productive benefits [] (p. 123). Social capital grounded in Indigenous entrepreneurs’ sense of collectivity can potentially promote “continuous learning, innovation, and adaptation to market opportunities” []. The consistency in the relationship between IXIM AC and the Indigenous entrepreneurs of the participant communities was identified as a relevant factor that effectively promotes mutual trust. This mutual trust has enabled the capacity of the participant Tseltal communities to increase the social capital of their entrepreneurial initiatives by expanding their stakeholders’ networks through those of IXIM AC. This is an interesting idea because social capital is a resource that grows the more it is shared by continuously generating prospects for building new strategic alliances []. The scholarship in this regard agrees that the creation of alliances in Indigenous contexts is a complex endeavor [], but also that it is worth it because it does not only create opportunities for mutual learning and innovation, as argued by Peredo [], but also has far-reaching impact in other levels such as “political influence, mobilization potential, and specific kinds of expertise” []. In addition, Indigenous entrepreneurs tend to use their enterprises as a means to achieve different kinds of purposes other than just those at the economic level, including the holistic wellbeing of their communities and self-determination and assertion over their territories [,,]. Based on these ideas, it can be argued that using and promoting social capital can be a key strategy for Indigenous entrepreneurs and their organizations in reaching impact at different levels to achieve their goals and diverse purposes.

The study findings suggest that the meaning of harmony in Tseltal culture is directly linked to an idea of communal balance that is supported by equality in everything related to the Nucleus of Tseltal community wellbeing and through the Four Elements of buhts’an qu’inal. The participants/collaborators in this study identified that having experience in practicing this communal balance in the participant Tseltal communities was the ground of IXIM AC’s rationale for focusing on specifically promoting the participation of Tseltal women entrepreneurs in initiatives of community economic development. The component of the Tseltal ideas of balance supported by equality is the window that enabled the participant Tseltal women entrepreneurs the opportunity of addressing their communities’ needs. By leveraging their traditional roles at the three levels of the Nucleus of Tseltal community wellbeing (individual–family–community), they reach new areas of action that, based on the findings of this study, are transforming the ways in which they perceive themselves. The findings of this study include evidence that the participant Tseltal women entrepreneurs are boosting their self-confidence and sense of empowerment, while feeling rooted in their traditional practices and local traditions.

Indigenous women entrepreneurs (IWE) are underrepresented in the entrepreneurship scholarship despite the fact that Indigenous women’s work is recognized as crucial in promoting community wellbeing [] while also having lower economic status and with women entrepreneurs more frequently having to confront and overcome acts of discrimination from the dominant society, especially in Indigenous communities that have primarily male-dominated cultures []. The findings of this study show that the active participation of women in entrepreneurial activities is effectively transforming their situation of vulnerability by promoting their self-confidence and empowerment through the development and success of their economic enterprises. However, there is an additional element that is crucial as a gender transformative activator in the unique approach of the participants/collaborators of this study: the space for self-reflection and analysis about their own endeavors. The results of this study suggest two ideas about gender transformative approaches. First, as Croce [] and Castañeda Salgado [] suggest, integrating intersectionality and positionality in undertaking research about Indigenous women in entrepreneurial ventures contributes to a better understanding of the unique perspectives and experiences of Indigenous women in entrepreneurship. Second, gender transformative impact in Indigenous communities cannot be achieved solely by promoting initiatives that promote Indigenous women’s self-confidence and empowerment, such as activities related to Indigenous entrepreneurship. These initiatives must also be guided and accompanied by practices that are aligned with the local traditions and women’s Indigenous knowledges. This second idea has at least two implications: 1. Organizations that aim to undertake gender transformative approaches to promote entrepreneurial initiatives in Indigenous communities need to have enough experience working with them in mutual-trust embedded relationships to understand the local traditional knowledges and practices; and 2. Working as a collaborator with IWE in promoting their enterprises requires one to make space for intersectionality and positionality, or in other words, self-introspection and analysis of the intersections and interdependence of the Indigenous women’s position and roles in their communities and with current and potential stakeholders. Furthermore, this needs to be undertaken in a way that is aligned with their traditional knowledges, practices, and languages.

IXIM AC’s initiative of avoiding direct translations and developing Tseltal concepts from Tseltal understanding to collectively reflect with the participant communities about specialized knowledge related to their entrepreneurial ideas emerged from this organization’s experience in participatory methods. Since the 1950s, participatory action approaches in Latin America have generated several experiences of participatory communication that seeks to address the needs of the most vulnerable in this region to generate social transformation []. Magallanes Blanco explains that the concept of Communication for Social Change emerged from these experiences and it has been defined as a process of dialogue and debate, based on tolerance, respect, equity, social justice, and the active participation of all, in which the communication process is more important than the results. The results of this kind of communication are only manifestations of the participation and reflection of the members of a community, but the critical aspect is that the reflection process is owned and undertaken by the members of the community to address their specific needs while promoting respectful dialogue [] (p. 44). This study’s results suggest that the participatory approach and the collective reflection that are part of the process of Communication for Social Change can be significant generators of locally grounded strategies that can serve Indigenous communities’ communication needs related to undertaking and developing initiatives of Indigenous entrepreneurship.

A common characteristic across Indigenous communities is their ability to overcome adversities despite the fact that most of them live in imposed situations of vulnerability [,]. For the last five hundred years, Indigenous communities have been facing and resisting the consequences of colonialism: from direct violent attacks to erase them and their cultures, through the plundering extraction of the natural resources of their traditional territories, to being forced to participate in paternalist programs that even today continue threatening their traditional ways of living and capacities for self-sufficiency and self-determination [,,]. Indigenous peoples’ capacity for resilience has been noted across multiple disciplines, and Indigenous entrepreneurship is not the exception. Diverse studies show that Indigenous entrepreneurs believe that their traditional knowledges and practices are strong, adventurous, and robust enough to enable paths to economic self-determination [].

Many of the consequences of the 2020–2021 Covid-19 pandemic have been devastating for many economies around the world, especially in regions where people were already in vulnerable economic situations, such as in Indigenous communities [,,]. However, the results of this research show that the challenges that emerged from the pandemic generated innovative ideas from the groups of Tseltal women entrepreneurs in each community, and there was renewed enthusiasm in leveraging the existing information technologies available in the region and even embracing the alternative of learning to use new ones. Resilience encompasses a series of capacities and abilities, which are acquired as a result of the interaction of individuals with their contexts. By being exposed to adverse events in these contexts, individuals are able to overcome their own limits of resistance through the generation of increasingly more efficient defense and protection processes and mechanisms. Some studies suggest that the six key elements in the process of developing resilience in Indigenous women in Mexico are social competence, family support, personal structure, strength and self-confidence, social support, and internal locus of control []. These six key elements were identified in the strategies undertaken by the collaborators/participants of this research in facing the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, in the case of this research study, there is an important factor that was crucial in the development of strategies: the work of the jTijaw.

The jTijaw were the ones who established the bonds of communication and trust among the Tseltal women of their groups and the members of IXIM AC. By leading the activities in their communities and proactively including new responsibilities in their roles, they minimized the transit of external actors across the participant communities. They followed up with the projects of the family gardens and the use of the installed ecotechnologies in their communities, and they also monitored and evaluated each of the activities of the distance training program. It was due to their continued work and motivation, grounded in their traditional knowledges and practices, that the project gained resilience and opened up new opportunities for expansion and innovation. The results showed that the jTijaw’s approach is grounded in their traditional roles. The critical aspect of grounding the work in related local practices speaks specifically of leveraging these practices, guided and led by local Indigenous elders and leaders, to provide the necessary strategies to face emergent challenges.

In studying Indigenous resilience, it is important to keep a skeptical perspective on the mainstream programs in the topic, since they are usually grounded in psychological and neoliberal agendas which usually focus on isolating the characteristics of resilience in the individual. Indigenous resilience is diverse; it can take many forms and be practiced in multiple ways distinctive of each Indigenous culture. Yet, studies show a common characteristic in the distinctive Indigenous processes of developing resilience: “in all cases, resilience was shifted from the individual to the collective, which aligns with an ecological, systems model that involves nesting layers of individual, family and community within a cultural and political context” [] (p. 119). Resilience grounded in collectivity surpasses the dimensions of individual resilience, reaching a level that relates more to the cultural dimension. Cultural resilience is “the capacity of a distinct community or cultural system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to retain key elements of structure and identity that preserve its distinctness” [] (p. 120). The results of this study suggest that the Nucleus of Tseltal wellbeing, grounded in the individual–family–community symbiotic dynamics across the Four Elements of Buhts’an qu’inal, is the framework in which the collaborators/participants’ strategic knowledge to solve problems is developed and accumulated. This strategic knowledge is communal and intrinsic to the Tseltal culture, which positions the capacities and work of the jTijaw and their groups at the level of cultural resilience, beyond simple individual adaptation.

5. Conclusions

Indigenous knowledges and ways of seeing life invite us to look at the aspects and models of development using the lenses of local communities, understanding their wise practices for community wellbeing. By integrating these perspectives, we have an opportunity to design new narratives for development that can allow us as a society to be in active partnership with nature. This partnership can in turn reposition Indigenous communities as active participants in nurturing life while fostering their distinctive knowledges that inform and guide local values and means of production, exchange, communication, and enjoyment. In this scenario, concepts such as sustainability, growth, and development become almost redundant, opening up the possibility of exploring local understandings of the conceptual frameworks of community wellbeing.

Another important dimension of this study’s contribution implies a call to the academics in the field of Indigenous entrepreneurship for collective action to position Indigenous communities’ needs, knowledges, and distinctive ways of understanding community wellbeing as the fundamental rationale for undertaking research (or at least at the same level as their personal or organizational interests). This implies a continued effort to keep in mind that in many cases the studies related to Indigenous entrepreneurship must start from unlearning the mainstream approaches to studying entrepreneurship, which are usually aligned to Western perspectives, and are oriented to “make room” for alternatives within capitalist structures. In the field of Indigenous entrepreneurship, researchers must be prepared to explore practices in which the economic purpose of the enterprises serves only as a means to weave a fabric consisting of intertwined social, cultural, spiritual, and environmental strands; and enterprises in which the generation of wealth or financial efficiency are not adequate indicators to define success for Indigenous entrepreneurs; and cases in which the ultimate goal is as simple—and complex—as achieving a communal enjoyment of life.

Funding

This research was funded by The International Development Research Centre (IDRC), grant number 109418-007; and by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT), grant number 570540.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the latest edition of the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS): Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. It was approved by the Trent University Research Ethics Committee, the Trent University Ph.D. in Indigenous Studies Research Ethics Committee, and the Trent Aboriginal Education Council in January 2020. These committees follow the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 (TCPS2 2018 version) ethical research framework. Specifically, this research follows the Tri-Council’s Chapter 9 methodological and ethical framework on research with Indigenous peoples, as well as the Ethical Guidelines for Research Best Practices outlined by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, and other emerging codes in Indigenous research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to alignment with the agreements made for this research in January 2020 with the participant communities, the Trent University Ph.D. in Indigenous Studies Research Ethics Committee, and the Trent Aboriginal Education Council. These committees follow the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 (TCPS2 2018 version) ethical research framework. Specifically, this research follows the Tri-Council’s Chapter 9 methodological and ethical framework on research with Indigenous peoples, as well as the Ethical Guidelines for Research Best Practices outlined by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, and other emerging codes in Indigenous research.

Acknowledgments

This study was undertaken in Tseltal territory in collaboration with the participant Tseltal communities and the organization IXIM, AC. This article was written in the Traditional Territory of the Michi Saagiig peoples of the Anishinabek Nation in the place known as Nogojiwanong encompassed by Treaty 20 and the Williams Treaty. This work is dedicated with special thanks to José Francisco Meneses Carrillo, xEduviges Méndez Guzman, Eva Guadalupe Sántiz López, Nasario Rubisel Parada Urbina, and Ana Vanessa Olvera Palacios, who are co-researchers in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Dana, L.P. Toward a multidisciplinary definition of Indigenous entrepreneurship. In International Handbook of Research on Indigenous Entrepreneurship; Dana, L.P., Anderson, R.B., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, L.P.; Anderson, R.B. International Handbook of Research on Indigenous Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hindle, K.; Lansdowne, M. Brave spirits on new paths: Toward a globally relevant paradigm of Indigenous entrepreneurship research. In International Handbook of Research on Indigenous Entrepreneurship; Dana, L.P., Anderson, R.B., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Adhikari, T. Development and conservation: Indigenous businesses and the UNDP Equator Initiative. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2006, 3, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development in Canada; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, L. Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing. Aboriginal Health, Identity, and Resource; Native Studies Press: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2000; pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Peredo, A.M.; McLean, M. Indigenous Development and the Cultural Captivity of Entrepreneurship. Bus. Soc. 2010, 52, 592–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ramírez, E.; Barba-Sánchez, V. Embeddedness as a Differentiating Element of Indigenous Entrepreneurship: Insights from Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNDPI. Indicadores socioeconómicos de los Pueblos Indígenas de México, 2015. Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/239921/01-presentacion-indicadores-socioeconomicos-2015.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Blume, A. Maya Concepts of Zero. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 2011, 155, 51–88. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, S.; Robertson, J.; Stuart, D. The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions. Curr. Anthropol. 2000, 41, 321–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, S.G. La civilización Maya; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Duverger, C. El Primer Mestizaje. La clave para entender el pasado Mesoamericano; Santillana, Conaculta, INAH, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Keme, E. Le Maya Q’Atzij, Our Maya Word; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vazquez, R.M.; Domínguez Flores, C.; Márquex, G. Long-Run Human Development in Mexico: 1895–2010. In Has Latin American Inequality Changed Direction? Bértola, L., Williamson, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Informe de Pobreza y Evaluación 2020. CHIAPAS; CONEVAL, Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social: Chiapas, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, J.C.; García-Chong, N.R.; Trujillo-Olivera, L.E.; Noriero-Escalante, L. Food insecurity and social vulnerability in Chiapas: The face of poverty. Nutrición Hospitalaria 2015, 31, 475–481. [Google Scholar]

- Román-Ruiz, S.I.; Hernández-Daumas, S. Seguridad alimentaria en el municipio de Oxchuc, Chiapas. Agricultura Sociedad y Desarrollo 2010, 7, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Gordillo, G.; Santana, R. Alimentación y salud de familias de áreas rurales de Chiapas. Ecosur en los medios, 16 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- González Díaz, M. Chiapas, el estado de México donde el consumo de refrescos es 30 veces superior al promedio mundial. Noticias UAM Cuajimalpa, 19 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, K. Community-Based Participatory Research; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borda, O.F. El problema de cómo investigar la realidad para transformarla; Tercer Mundo: Bogotá, Colombia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Borda, O.F. Orígenes universales y retos actuales de la IAP. Análisis político 1999, 38, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Borda, O.F. La investigación acción en convergencias disciplinarias. Revista paca 2009, 1, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaudry, A. Researching the Resurgence: Insurgent Research and Community Engaged Methodologies in 21st-Century Academic Inquiry. In Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive Approaches; Brown, L.A., Strega, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Grounded Theory and the Politics of Interpretation. In The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore, 2007; pp. 454–471. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Campos Navarrete, M. Experiencing Buhts’ An Qu’Inal from sHachel Jwohc’a’Tel Through Sna’el Ya’beyel Stuc Te Bin Ay Ma’yuc: Fostering Local Economic Development in Tseltal Terms. Ph.D. Thesis, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2021; pp. 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of social capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Campos Navarrete, M. Fostering Sustainable Development through Cross-Sector Collaboration in University Innovation Initiatives: A Case Study of the Trent Research & Innovation Park. Master’s Dissertation, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peredo, A.M. Nothing Thicker than Blood? Commentary on Help One Another, Use One Another: Toward an Anthropology of Family Business. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide Lozano, V.; Arroyo Moliner, L.; Murillo, D.; Buckland, H. Understanding the effects of social capital on social innovation ecosystems in Latin America through the lens of Social Network Approach. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2019, 29, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L. Alliances: Re/Envisioning Indigenous-Non-Indigenous Relationships; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.; Shpuniarsky, H.Y. Indigenous Alliances and Coalitions. In Alliances: Re/Envisioning Indigenous-Non-Indigenous Relationships; Davis, L., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010; pp. 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Peredo, A.M.; Anderson, R.B.; Galbraith, C.S.; Honig, B.; Dana, L.-P. Towards a theory of indigenous entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2004, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.-P. Indigenous entrepreneurship: An emerging field of research. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2015, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ratten, V.; Dana, L.-P. Gendered perspective of indigenous entrepreneurship. Small Enterp. Res. 2017, 24, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, F. Indigenous women entrepreneurship: Analysis of a promising research theme at the intersection of Indigenous entrepreneurship and women entrepreneurship. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2020, 43, 1013–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda Salgado, M.P. Etnografía Feminista. In Investigación feminista Epistemología, metodología y representaciones sociales. Mexico: UNAM Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades; Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias. Facultad de Psicología: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Magallanes Blanco, C. La comunicación para el cambio social, un proceso de trabajo por la transformación social. Revista Rúbricas 2015, 7, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, D. Coming Full Circle: Indigenous Knowledge, Environment, and Our Future. Am. Indian Q. 2004, 28, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado Aráoz, H. Ecología política de los regímenes extractivistas. De reconfiguraciones imperiales y re-ex-sistencias decoloniales en Nuestra América. Bajo el Volcán Revista del Posgrado de Sociología 2016, 16, 11–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil Batalla, G. Etnodesarrollo: Sus premisas jurídicas, políticas y de organización. In Obras escogidas de Guillermo Bonfil Batalla Tomo 2; INI/INAH/CIESAS/CNCA: Mexico City, Mexico, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hindle, K. The renaissance of Indigenous entrepreneurship in Australia. In International Handbook of Research on Indigenous Entrepreneurship; Dana, L.P., Anderson, R.B., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Power, T.; Wilson, D.; Best, O.; Brockie, T.; Bearskin, L.B.; Millender, E.; Lowe, J. COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples: An imperative for action. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2737–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz de León-Martínez, L.; de la Sierra-de la Vega, L.; Palacios-Ramírez, A.; Rodriguez-Aguilar, M.; Flores-Ramírez, R. Critical review of social, environmental and health risk factors in the Mexican indigenous population and their capacity to respond to the COVID-19. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 733, 139357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesar, S.; Abraham, R.; Lahoti, R.; Nath, P.; Basole, A. Pandemic, informality, and vulnerability: Impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods in India. Dev. Stud./Revue canadienne d’études du développement 2021, 42, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuan-Meza, X.S.; Landeros-Olvera, E.A.; Cossío-Torres, P.E. Validity of a resilience scale (RESI-M) in Indigenous women in Mexico. Cadernos de saude publica 2018, 34, e00179717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.; Mitchell, T.; Arseneau, C. Re-evaluating resilience: From individual vulnerabilities to the strength of cultures and collectivities among indigenous communities. Resilience 2015, 4, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, S. Cultural resilience, identity, and the restructuring of political power in Bolivia. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property, Bali, Indonesia, 19–23 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).