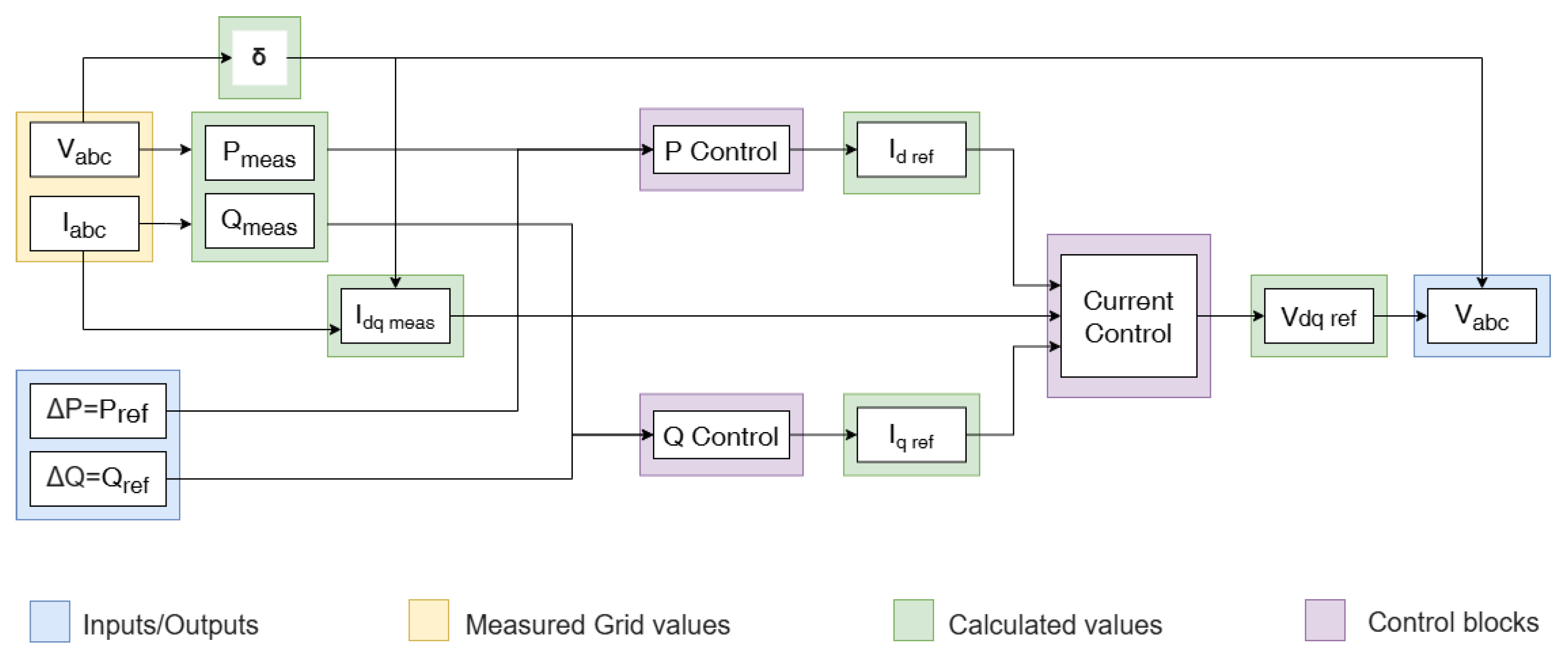

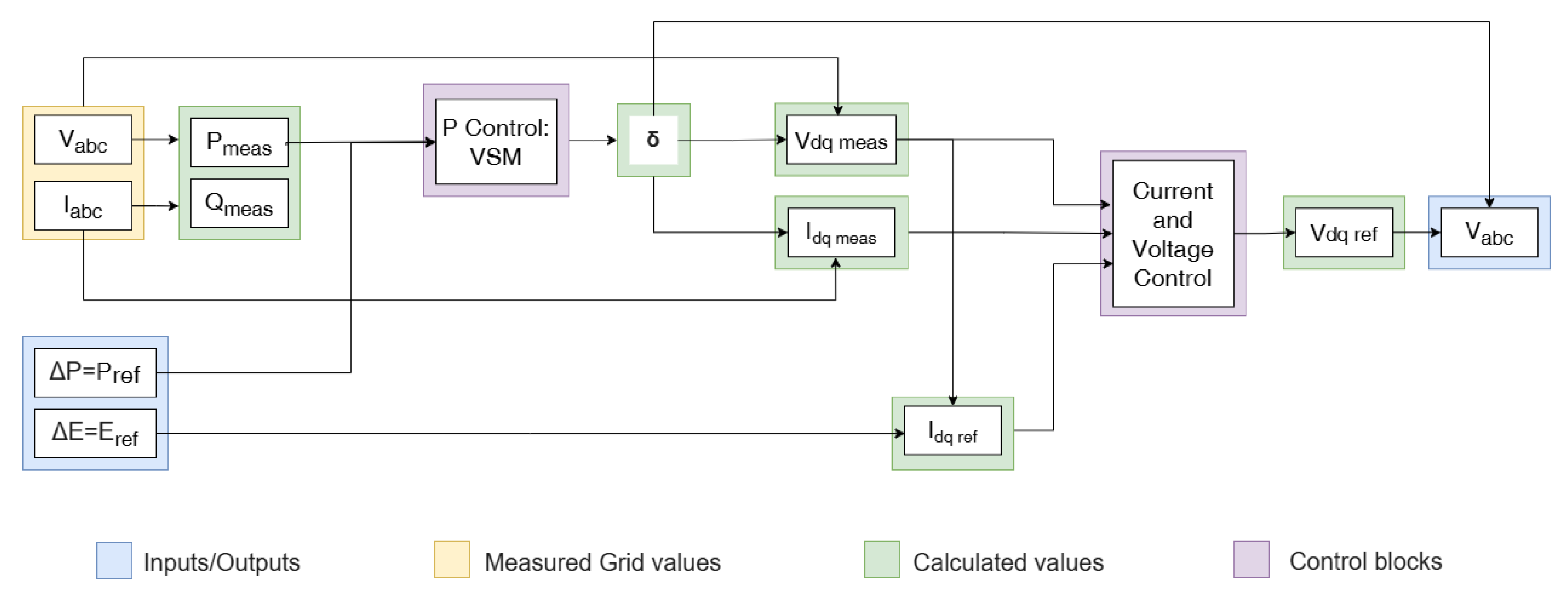

4.2.1. Islanded Operation

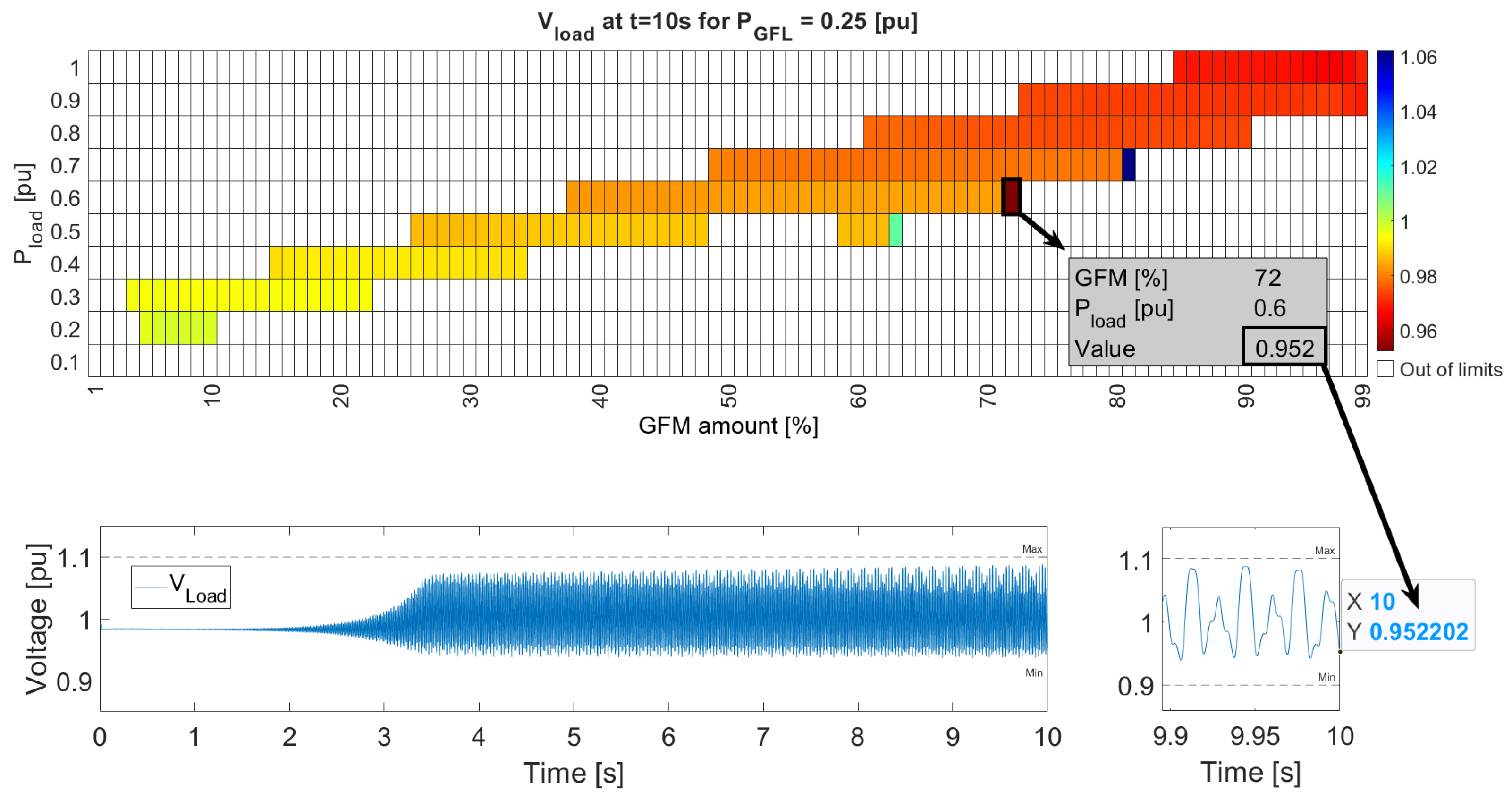

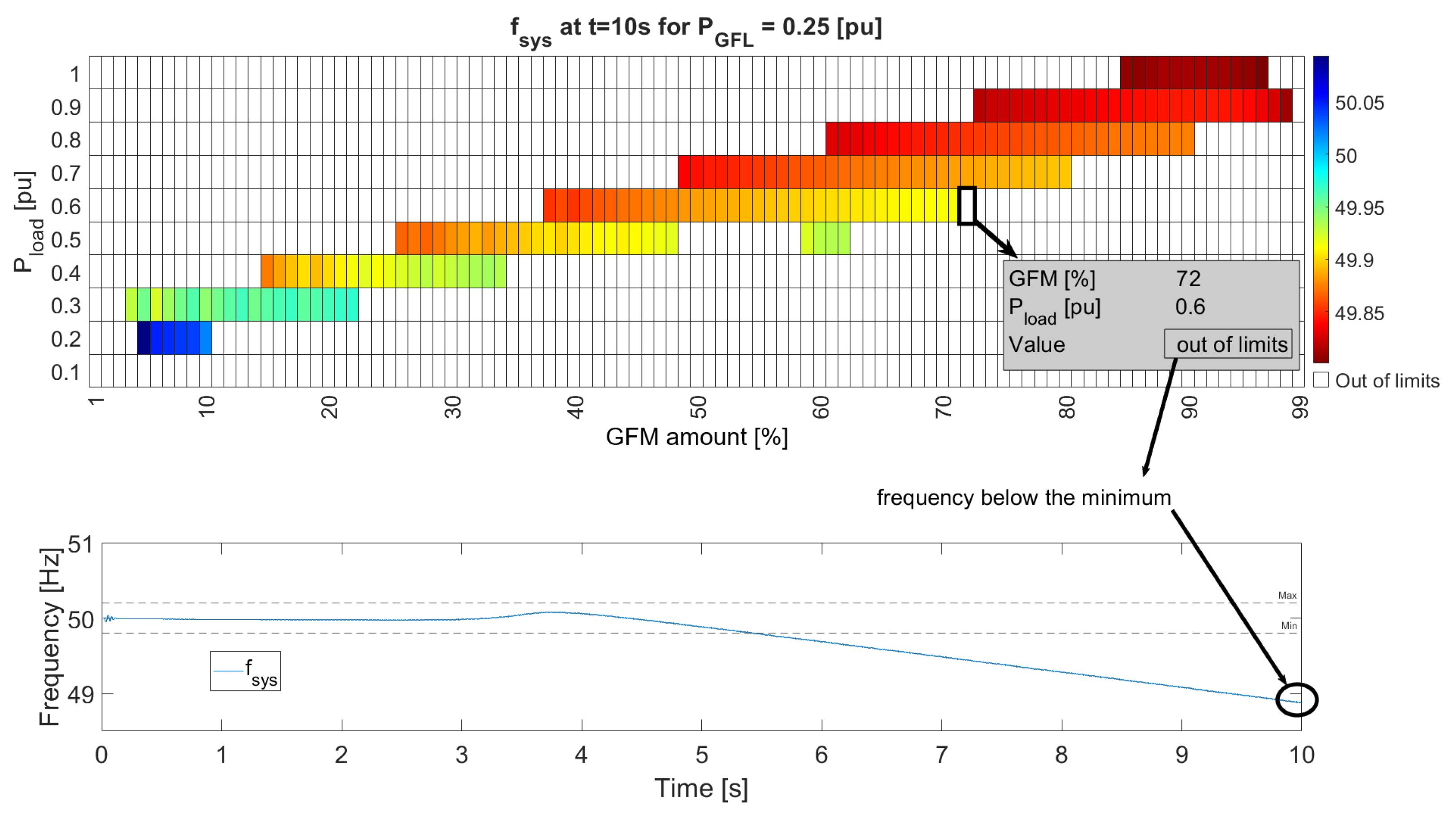

For the islanding operation, four different scenarios were tested in order to identify regions with acceptable operation conditions for the load voltage and the MG frequency. In this case, the external grid was completely deactivated and therefore the GFM inverter was set as the slack or swing bus, in order to be able to perform the load flow. This also implies that the GFM inverter is capable of adapting its active and reactive power output in order to meet the system conditions. The active power reference of the GFL inverter was tested with values of 0.25 pu, 0.5 pu, 0.75 pu, and 1 pu, implying different availability of the source connected.

The simulation on islanded operation was executed for 10 s with no event happening, in order to evaluate if the given conditions represented an acceptable operating point. For every given set point of the GFL inverter, simulations were executed changing the GFM amount

from 1% to 99% and the load active power set point from 0.1 pu to 1pu in steps of 0.1 pu.

Table 5 summarizes the information used for the simulations.

The variables recorded were voltage and frequency. The last value of these two variables for each simulation was compared to the long term operational voltage limits of and the frequency limits of 49.8 Hz and 50.2 Hz. Even if the behavior of the variables did not show an oscillatory or unstable behavior (which is not displayed), for the evaluation of each case it was considered that if the voltage or frequency falls outside of this limits, the operating point is considered unacceptable.

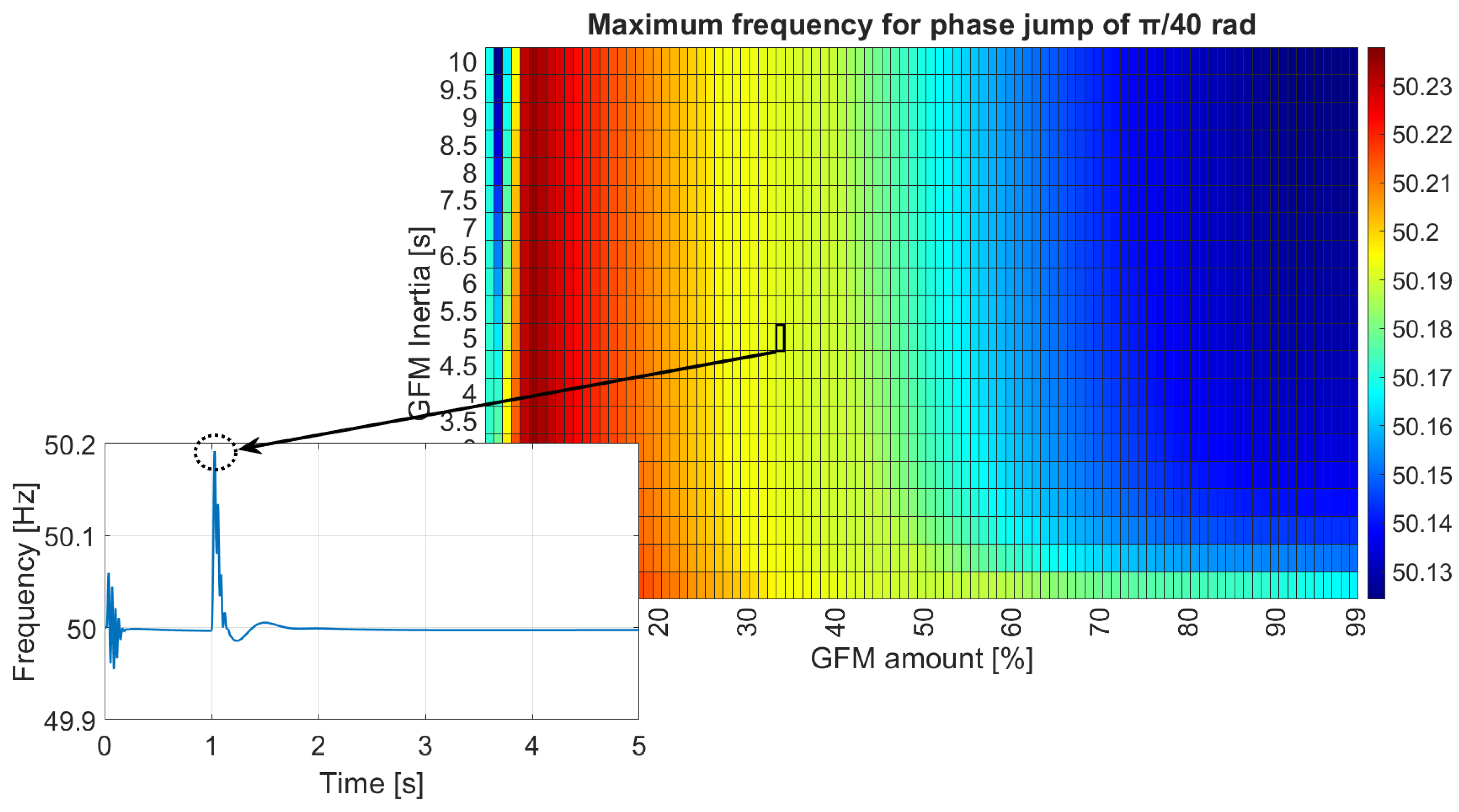

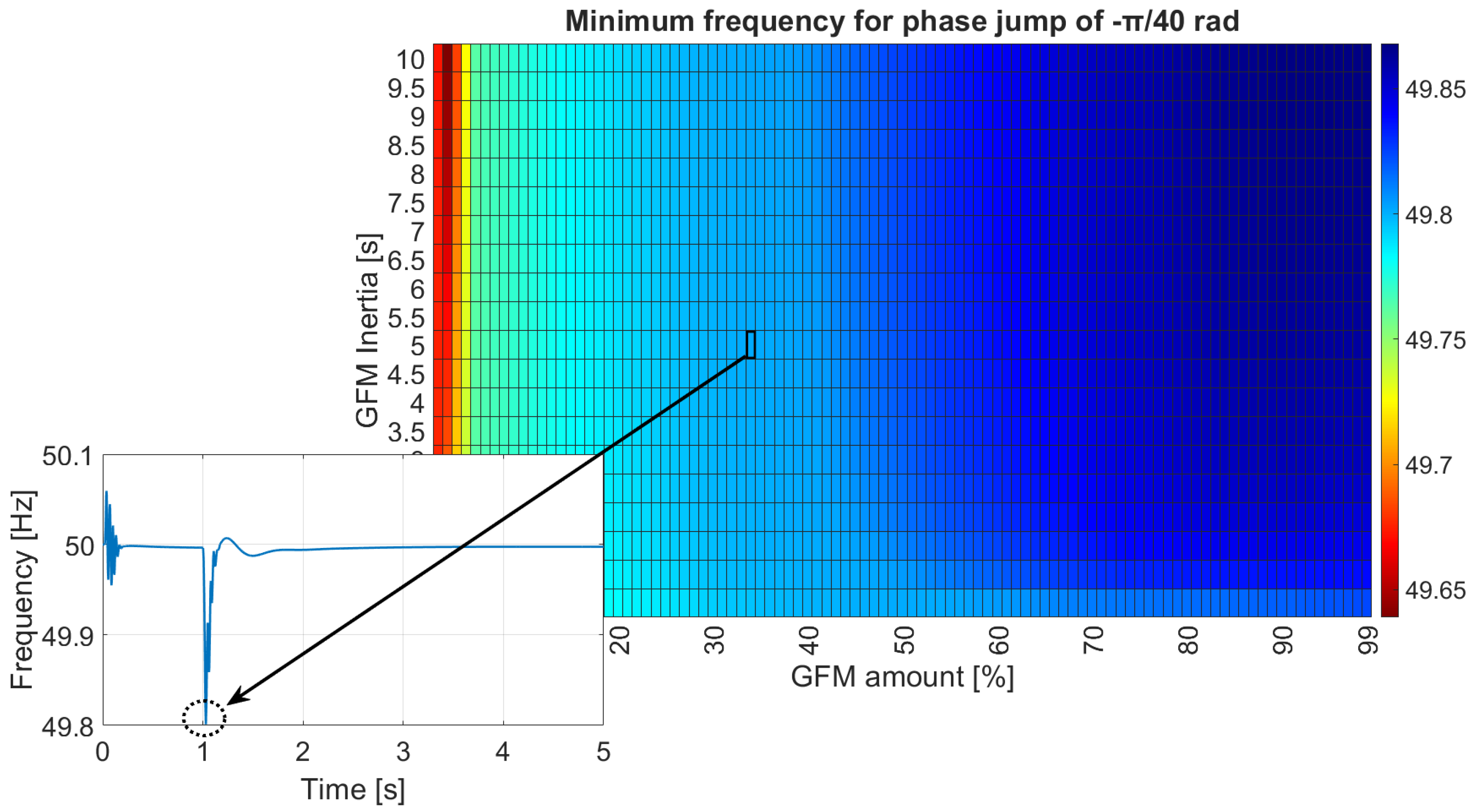

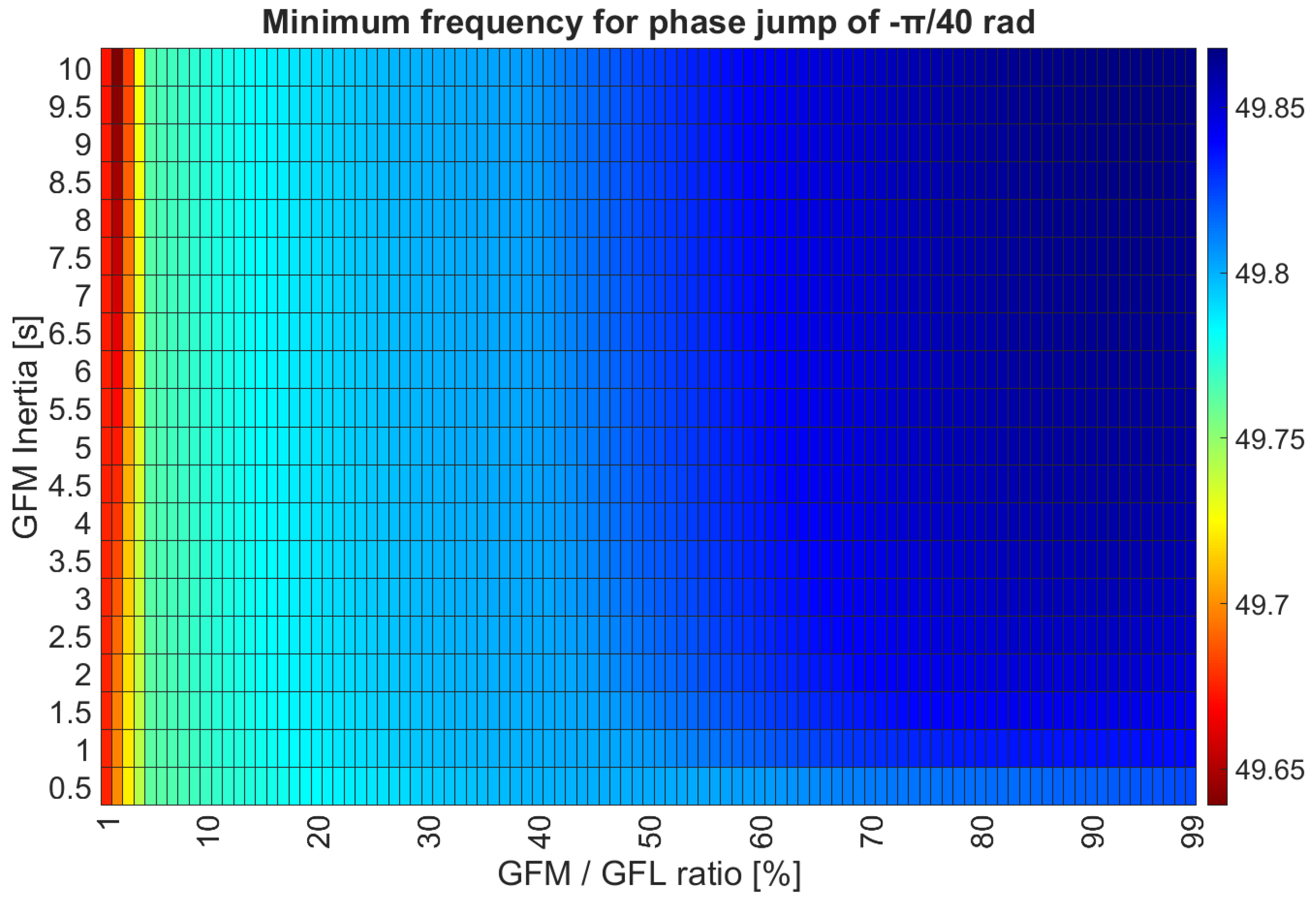

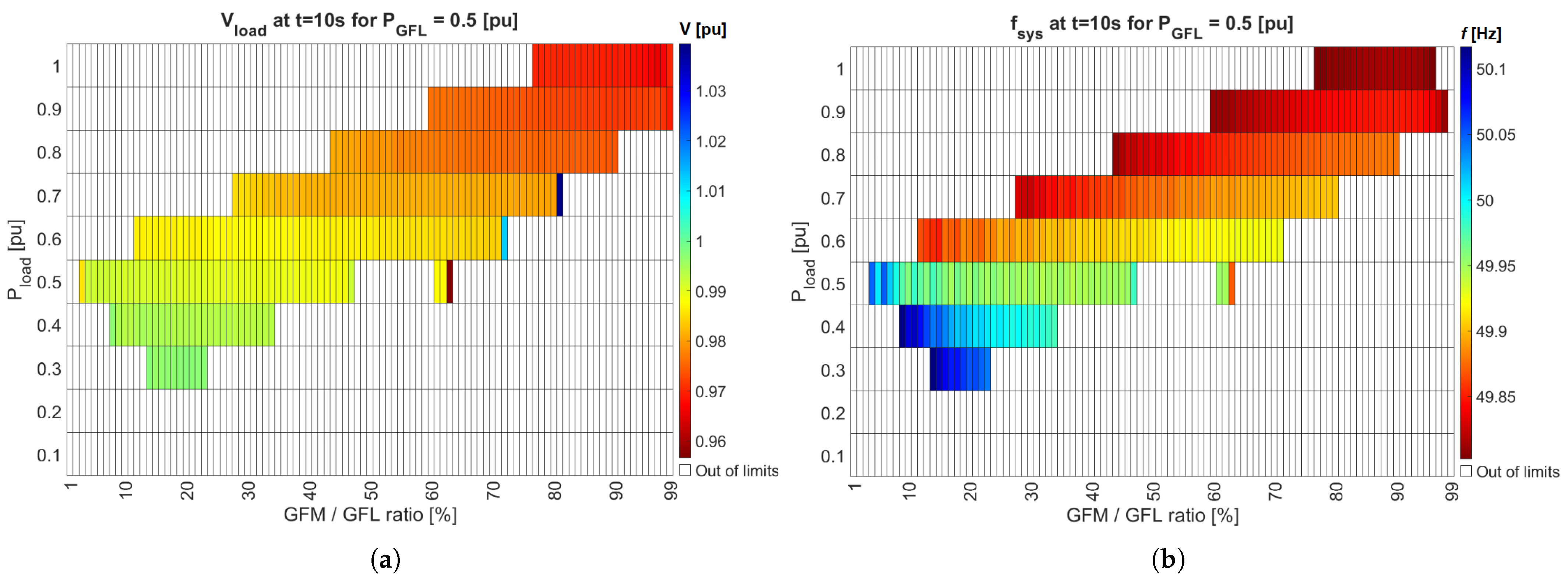

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show the results illustrated as heatmaps. The white areas show the points where the corresponding variable was outside of the defined acceptable limits, while the color region shows the points were the variable presented a value within the limits. The color indicates the precise value as labeled by the side bar. A detailed analysis of the results for each case will be further provided.

Case 1,

pu:

Figure 11 shows the voltages and frequencies obtained for the GFL inverter active power set point of 0.25 pu. It is clear the there is a linear tendency for the acceptable operating region. That means, the higher the load active power, the higher the requirement of GFM amount in the system in order to obtain a stale operating point, keeping the

constant at 0.25 pu.

The acceptable points for the voltage were achieved for reference points from 0.2 pu to 1 pu and for GFM amounts from 4% to 99%. The second tendency that can be observed is that the higher the load active power, the lower the final voltage value. In this sense, the best operating point (closest to the 1.00 pu) was located at pu and from 5% to 10%, which is a relatively small operating range.

With respect to the frequency, an overall similar region was observed, with the same linear tendency. The acceptable points for the frequency were achieved for reference points from 0.2 pu to 1 pu as well but from 4% to 98% with respect to the GFM amount. The second tendency that can be observed is that the higher the load active power, the lower the final frequency value. However, the best operating point (blue region, closest to the 50 Hz) was located at the lowest between 0.2 pu and 0.3 pu, with an at around 10% to 20%.

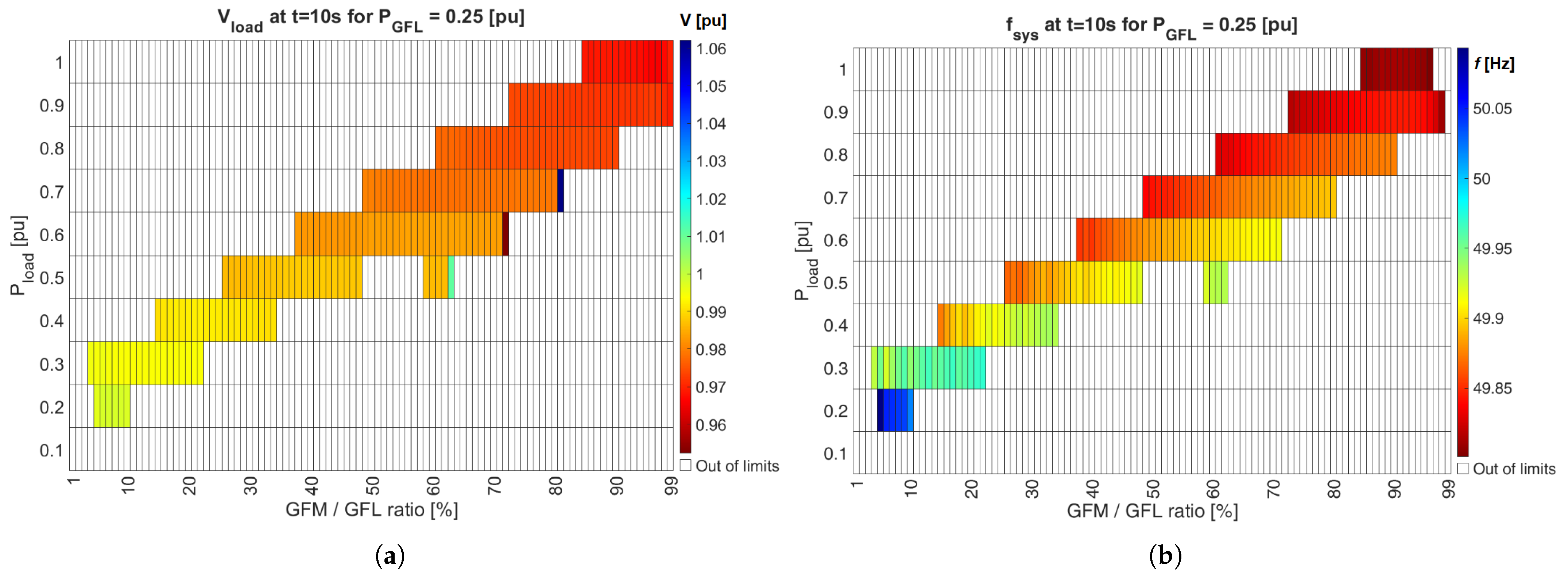

Case 2,

pu:

Figure 12 shows the voltages and frequencies obtained for the GFL inverter active power reference of 0.5 pu. In this case, the same linear tendency of the values for the acceptable operating region is observed. That means that, keeping the

constant at 0.5 pu, the higher the load active power, the higher the requirement of the GFM amount in the system in order to obtain a stale operating point. However, in this case, the range of GFM amounts for which the operation is within the limits for each

operating point is wider. This means that stability can be reached with higher and lower GFM amounts at each load operating point.

It is worth noting, however, that the acceptable points for the voltage were achieved for operating points from 0.3 pu to 1 pu, which is 10% more of the minimum load active power limit than the previous case. This implies that, for the given reference of GFL active power, the load must be at least 0.3 pu in order to be able to operate within the acceptable limits.

Also, for the lower load amounts in this case, higher amounts of GFM are needed, compared to the previous case. Acceptable values were reached for GFM amounts from 2% to 99% for the voltage. Similar to the previous case, the second tendency that can be observed is that the higher the load active power, the lower the final voltage value. In this sense, the best operating point (closest to the 1.00 pu) was located for between 0.3 pu and 0.4 pu, with from 14% to 23% and 8% to 34%, respectively, which is still a relatively small but larger operating range compared to the previous case.

With respect to the frequency, an overall similar region was observed. The acceptable points for the frequency were achieved for operating points from 0.3 pu to 1 pu as well, and from 3% to 98% with respect to the GFM amount. Similar to the previous case, the second tendency that can be observed is that the higher the load active power, the lower the final frequency value. However, the best operating point (closest to the 50 Hz) was located for at 0.4 pu and from 17% to 34%, which is still a relatively small but larger operating range compared to the previous case.

Case 3,

pu:

Figure 13 shows the voltages and frequencies obtained for the GFL inverter active power reference of 0.75 pu. In this case, the linear tendency of the values for the acceptable operating region is still observed, but not as clear as in the previous two cases. In this case, the range of GFM amounts for which the operation is within the limits for each

operating point is wider and starts to take a “V” shape. This means that acceptable operating points can be reached with higher and lower GFM amounts at each load operating point, but for lower load operating points the acceptable ranges of

are smaller.

It is worth noting, however, that the acceptable points for the voltage were achieved for operating points also from 0.3 pu to 1pu, which is similar to the previous case. Also, for the lower load amounts in this case, higher amounts of GFM are needed, compared to the previous case, and the acceptable range for 0.3 pu is much narrower. Acceptable values were reached for GFM amounts from 3% to 99% for the voltage. Similar to the previous case, the second tendency that can be observed is that the higher the load active power, the lower the final voltage value. In this sense, the best operating point (closest to the 1.00 pu) was located for at 0.4 pu and from 20% to 34%, which is still a relatively small and similar operating range compared to the previous case. It is important to mention that in general, the voltages resulted in a tendency to be lower than 1 pu.

With respect to the frequency, an overall similar region was observed. However, the acceptable points for the frequency were achieved for operating points from 0.4 pu to 1pu and from 7% to 98% with respect to the GFM amount. Similar to the previous cases, the second tendency that can be observed is that the higher the load active power and the higher the GFM amount, the lower the final frequency value. However, the best operating point (green areas, closest to the 50 Hz) was located for between 0.5 pu and 0.7 pu and for various ranges of from around 12% to around 46%, depending on the value. This is a relatively larger operating range compared to the previous cases.

Case 4,

pu:

Figure 14 shows the voltages and frequencies obtained for the GFL inverter active power set point of 0.75 pu. In this case, the linear tendency of the values for the acceptable operating region is even less clear than the previous cases, and instead the “V” shape is more predominant. In this case, the range of GFM amounts for which the operation is within the limits for each

operating point is larger. This means that stability can be reached with higher and lower GFM amounts at each load operating point.

It is worth noting that the acceptable points for the voltage were achieved for operating points also from 0.4 pu to 1pu. Also, for the lower load amounts in this case, higher amounts of GFM are needed, compared to the previous cases, and the acceptable range for 0.4 pu is much narrower. Acceptable values were reached for GFM amounts from 6% to 99% for the voltage. Even though the tendency of the higher the load active power, the lower the final voltage value is still observed, the values in general remain much closer to the 1 pu, with a few exceptions at the limits, compared to the previous cases. In this sense, the best operating point (light blue region, closest to the 1.00 pu) was located for between 0.4 pu and 0.6 pu and from 20% to 45% depending on the value, which is a relatively larger operating range compared to the previous cases. This exhibits the best voltage behavior so far from the four cases.

With respect to the frequency, an overall similar region was observed, presenting the same “V” shape. The acceptable points for the frequency were also achieved for operating points from 0.4 pu to 1pu but from 10% to 98% with respect to the GFM amount. Similar to the previous cases, the second tendency that can be observed is that the higher the load active power and the higher the GFM amount, the lower the final frequency value. However, the best operating point (green areas, closest to the 50 Hz) was located for between 0.5 pu and 0.9 and for a varied range of from around 17% to around 50%, depending on the value. This is a relatively larger operating range compared to the previous cases.

It is important to address the few cases at the edge of the color area in each plot which do not follow the tendency, but resulted in acceptable values. These were the result of an unstable case, for which by chance the last value falls into the acceptable range. However, they should not be considered part of the acceptable area. Two specific cases were simulated dynamically and are described in

Appendix B.

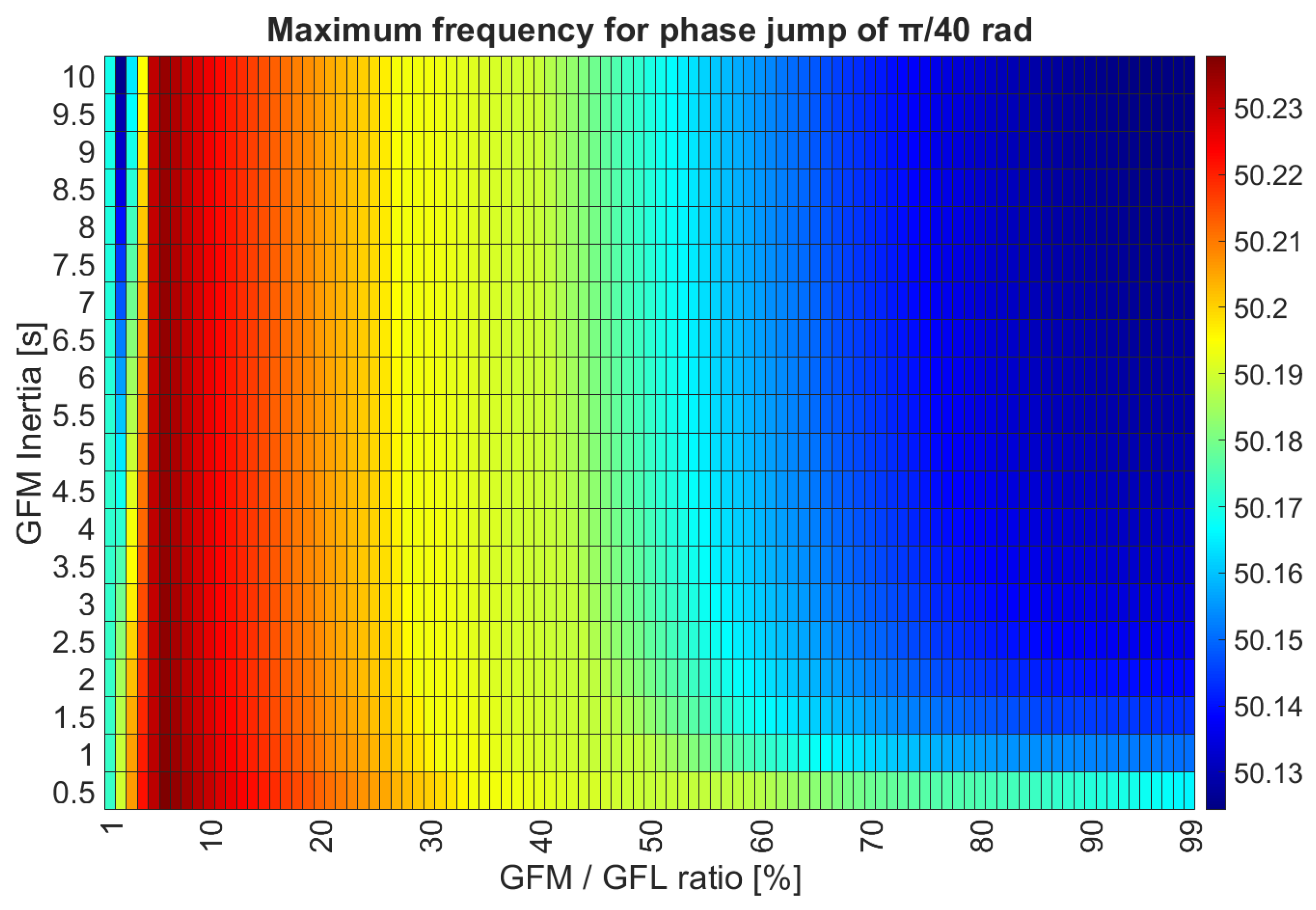

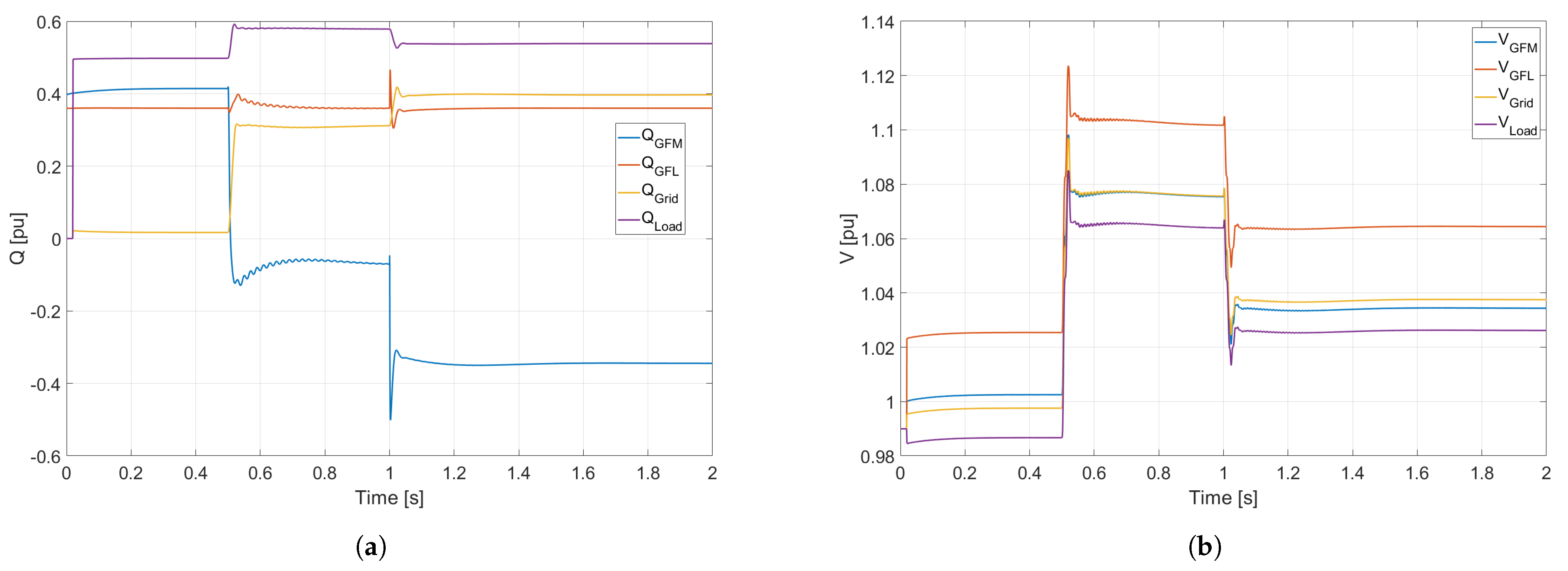

4.2.2. Disconnection Process Survivability

As mentioned previously, the disconnection process was tested in order to determine if the MG would survive the disconnection or not, by analyzing the post-separation states achieved. Initially the MG is operating connected to the grid and at time s the circuit breaker at the PCC opens, and the simulation runs for a total of 10 s. The behavior after the disconnection was analyzed in order to determine if the conditions are permanently acceptable, temporarily acceptable subject to changes in the MG or unacceptable.

Four cases were simulated by using four different combinations of reference values for GFM amount

, active power reference of the GFM, GFL inverters and the load, which are shown in

Table 6. At every simulation, the case without disconnection was first simulated, then the islanded case in order to establish the required conditions for acceptable operation before and after separating. Then, the disconnection was tested in order to identify if the system is able to reach acceptable operating conditions.

It is worth noting that, for the grid-connected case, the external grid was set as the slack bus, while for the islanded mode the GFM inverter was set as the slack bus. During the disconnection process, the slack cannot be dynamically changed, so initially the slack is the external grid and after, the MG loses its slack or swing bus. For this reason, the post-disconnection states may vary from the islanded ones since mathematically the simulation has a different reference.

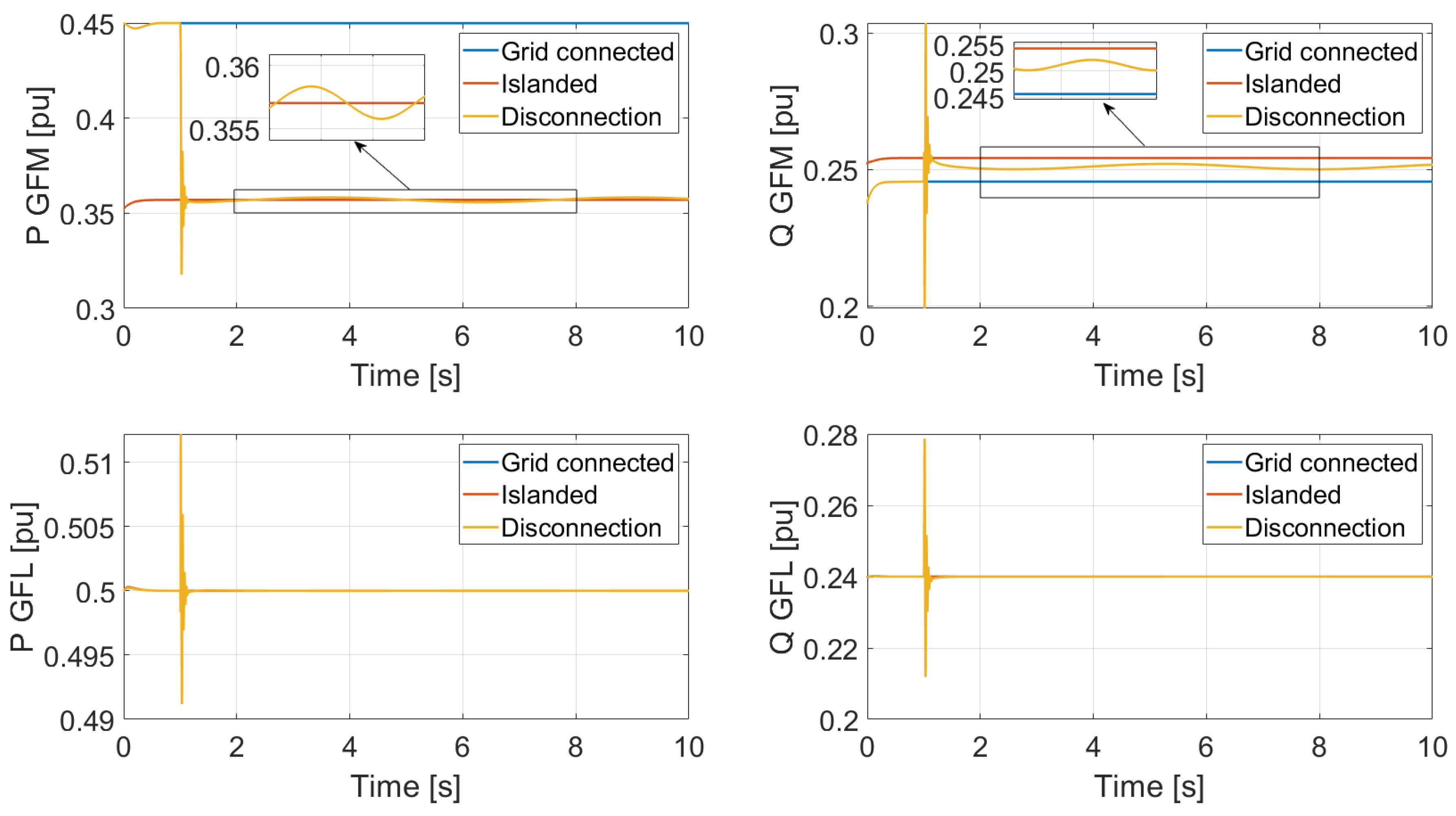

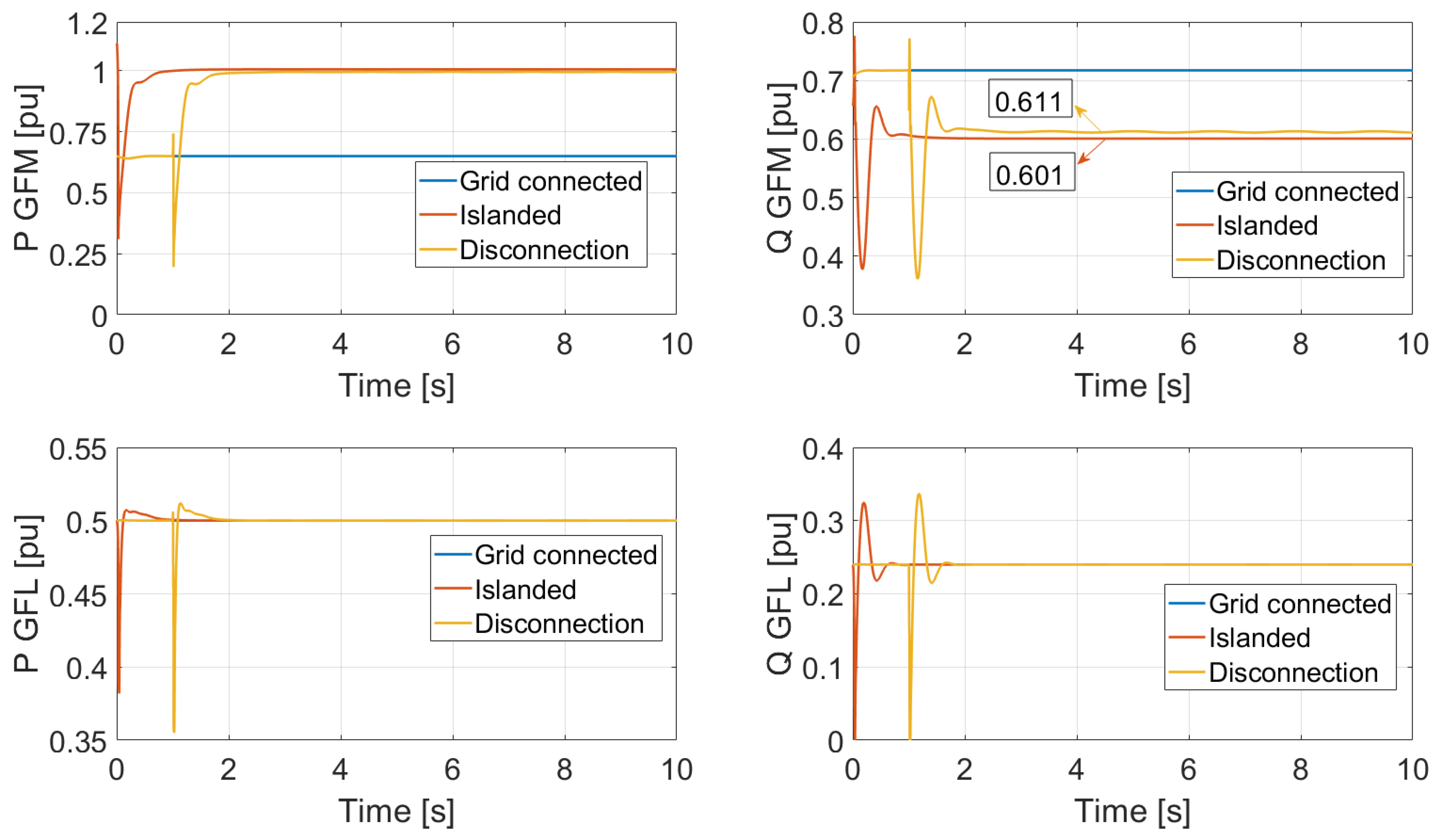

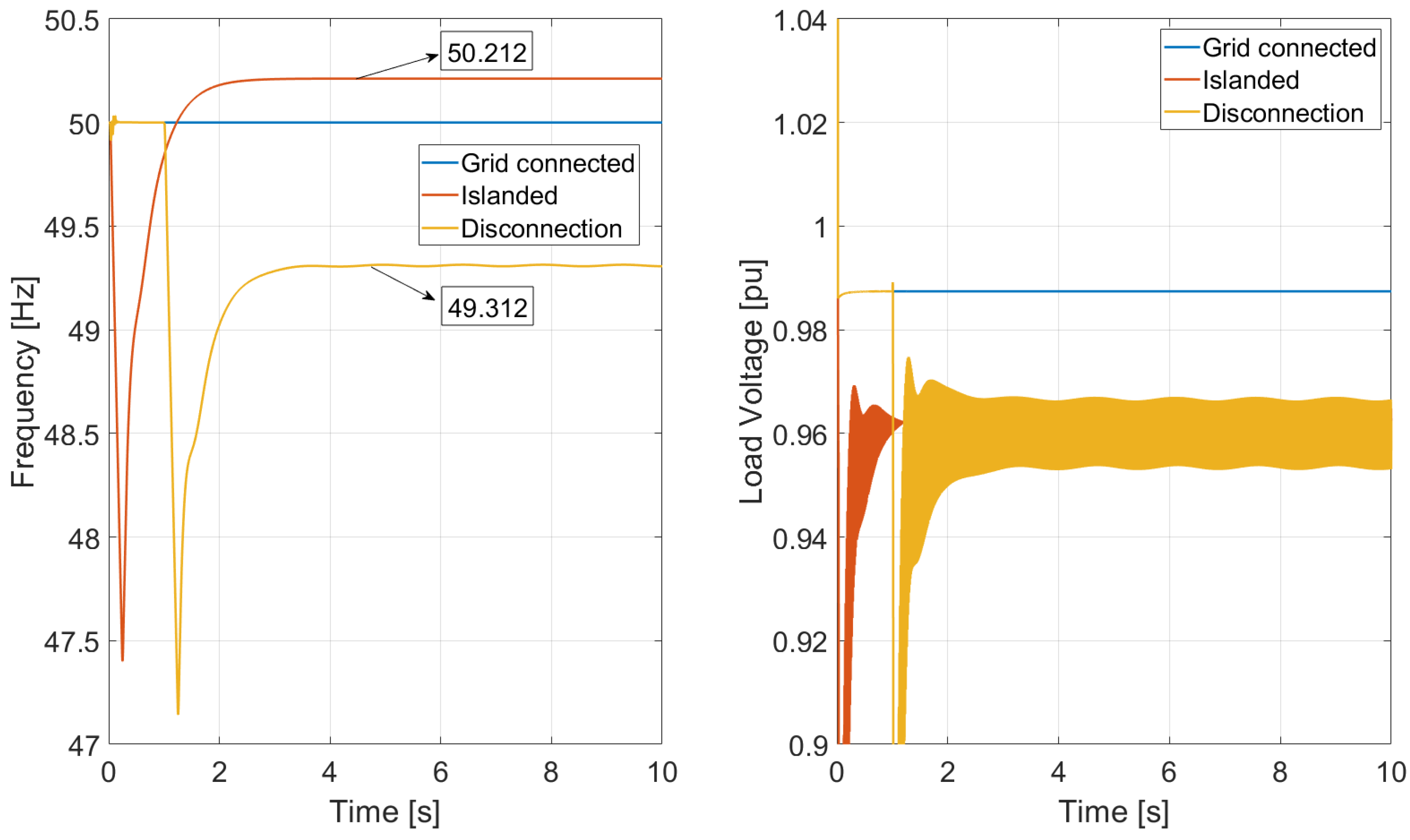

The simulation results and a description for each case are provided next. At each plot, the blue line displays the behavior without disconnection (grid connected), the red line the behavior starting at islanded operation, and in yellow the behavior with the disconnection happening at s.

Case 1:

Figure 15 shows the results for active and reactive power of both GFM and GFL inverters for Case 1. As it can be seen, this case is acceptable since all the variables were able to fully jump from the grid-connected condition to the islanded stable condition after the disconnection. In this case, only the GFM inverter reactive power presented a substantial change, reaching the new reference point after a transient period of about 1 s. The GFL inverter did not experience any change in the reference, meaning that the survivability depends completely on the ability of the GFM inverter to adapt its reference points.

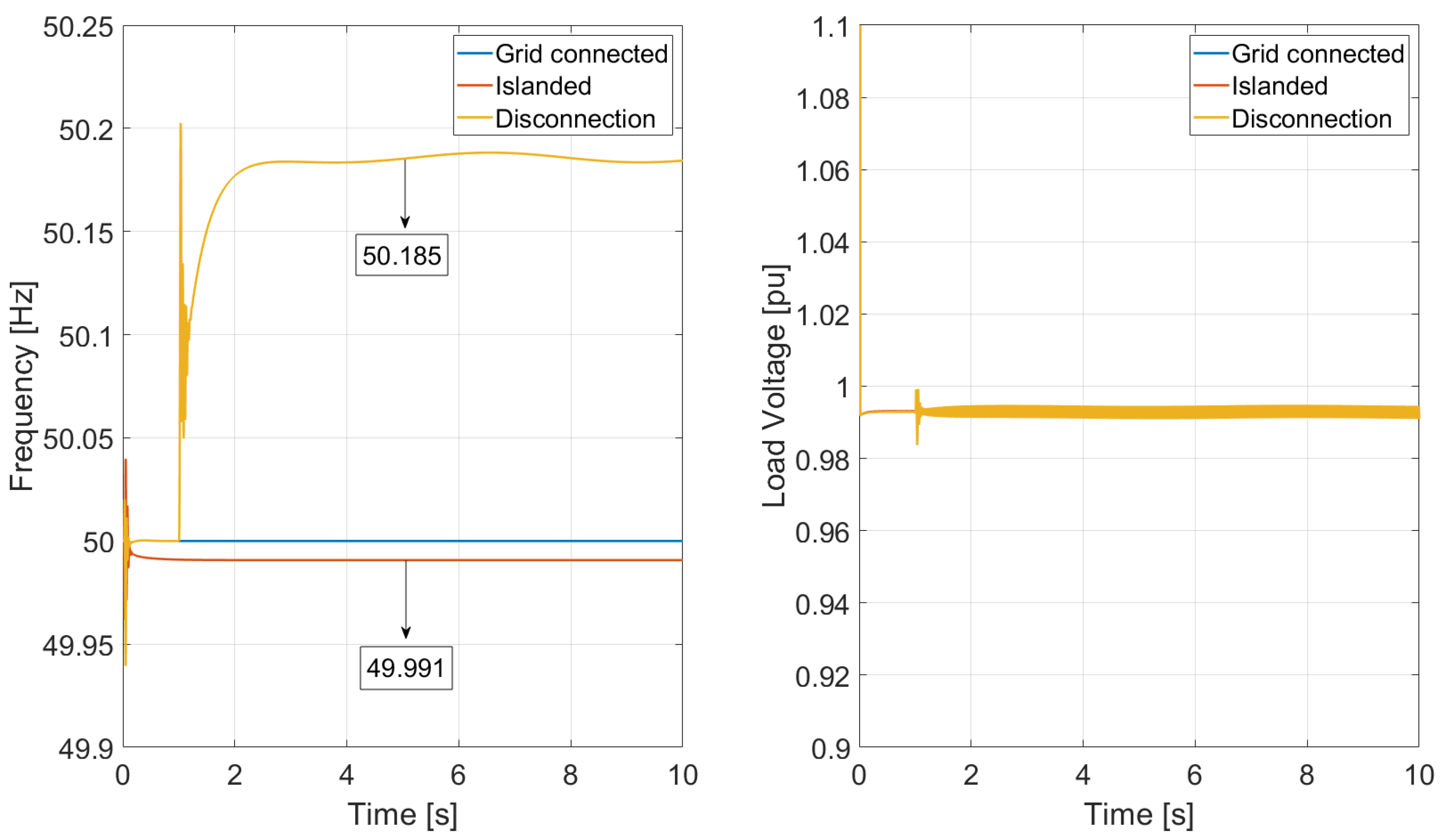

Figure 16 displays the system frequency and load voltage for the Case 1. They confirm the survivability after the disconnection since both variables remain inside the acceptable operation limits.

Case 2:

Figure 17 shows the results for active and reactive power of GFM and GFL inverters for Case 2. As it can be seen, this case is also acceptable since the active power was able to fully jump from the grid-connected condition to the islanded stable condition after the disconnection. In this case, the GFM inverter both active and reactive power experienced a change. The active power jumped from 0.45 pu to 0.35 pu while the reactive power in this case experienced a much smaller jump from 0.245 to around 0.25 pu. In any case, the new reference point was reached after a very short transient period. However, both active and reactive power of the GFM present oscillations after the disconnection which need to be addressed in a short period of time to avoid resonances.

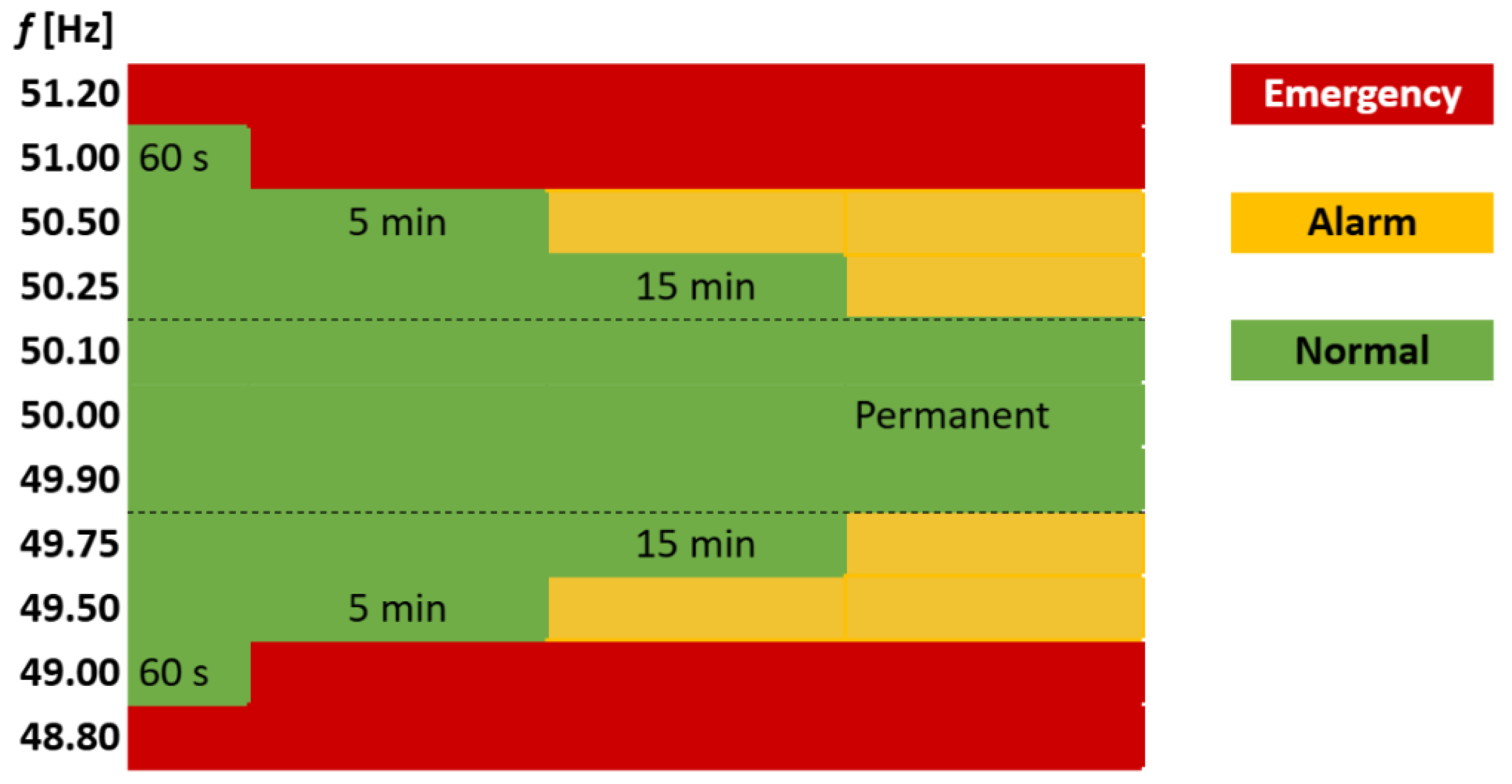

Figure 18 displays the system frequency and load voltage for the Case 2. They confirm the survivability after the disconnection, since both variables remain inside the acceptable operation limits. However, this value of frequency (50.185 Hz) is acceptable for a period of 15 min before reaching an alarm state as shown in

Figure 1. This means that the MG has 15 min after the disconnection to take action in order to reach the permanently acceptable operating point. These actions could be generation curtailment or a change in the GFM inverter reference point in order to balance the over-frequency state. The voltage presents some oscillations caused by the GFM inverter reactive power observed in

Figure 17, which also need to be addressed soon after the disconnection.

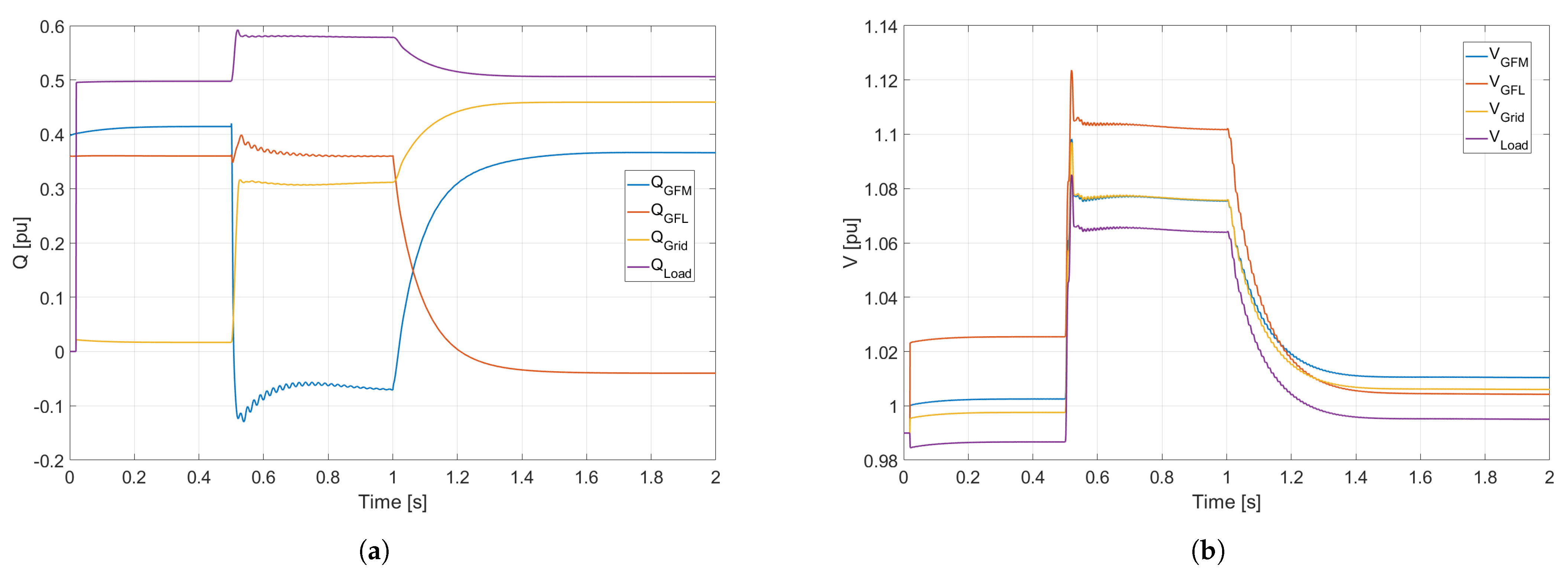

Case 3:

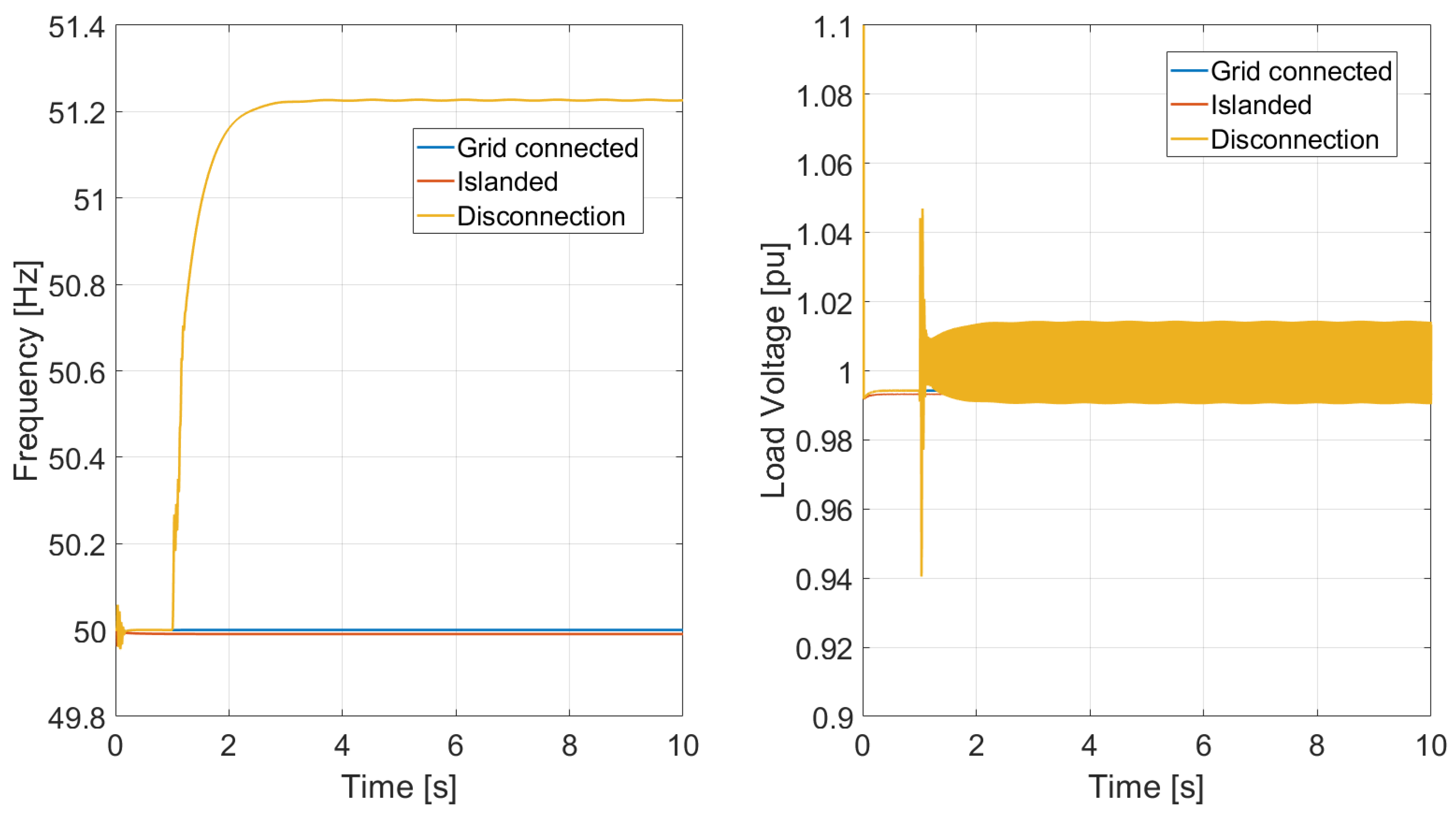

Figure 19 shows the results for the active and reactive power of GFM and GFL inverters for Case 3. This case is not acceptable since the GFM inverter active power was not completely able to jump from the grid-connected condition to the islanded stable condition after the disconnection. The reference value for the GFM active power in islanded operation for this case is 0.357 pu, but the power was able to fall only to around 0.385 pu and with some oscillations. The reactive power was able to jump to the reference value, but it shows some oscillations as well.

The unbalance of around 3% in active power caused the frequency to reach an unacceptable value. Despite exhibiting stable behavior, in real-life applications the frequency shown in

Figure 20 is not acceptable. According to

Figure 1, the frequency reached after disconnection would make the system go into emergency state, leaving almost no time for action to be taken. Similarly, the voltage presents high-frequency oscillations with a magnitude of around 2% as shown also in

Figure 20. Despite remaining inside the acceptable limits, these oscillations are not acceptable and may result in resonances.

Case 3 was made acceptable by adjusting the reference active power of the GFM inverter to 0.5 pu and the GFM amount

to 45%. The results are shown in

Figure 21. It can be seen that a relatively small difference reached in the GFM inverter active and reactive power results in the frequency reaching a value which is inside the acceptable range (50.189 Hz) and the voltage to have a much less oscillatory behavior.

Case 4:

Figure 22 shows the results for the active and reactive power of GFM and GFL inverters for Case 4. This case was also not acceptable since the GFM inverter reactive power was not completely able to fully jump from the grid-connected condition to the islanded stable condition after the disconnection. The reference value for the GFM reactive power in islanded operation for this case is 0.601 pu but the power was able to fall only to around 0.611 pu and with some oscillations.

The unbalance of around 1% in reactive power caused the voltage to present high-frequency oscillations with a magnitude of around 2% as shown also in

Figure 20. Despite remaining inside the acceptable limits, these oscillations are not acceptable and may result in resonances. The frequency also exhibits an unacceptable value. Despite having stable behavior, in real-life applications, the frequency shown in

Figure 23 of 49.312 Hz is not acceptable for long-term operation. According to

Figure 1, the frequency reached after disconnection would make the system go into emergency state after 60 s, leaving almost no time for action to be taken.

Case 4 was made acceptable by adjusting the GFM amount

to 75%. The results are shown in

Figure 24. It can be seen that a significant difference reached in the GFM inverter active and reactive power results in the frequency and voltage reaching values inside the acceptable ranges (49.805 Hz and 1 pu, respectively) and damping the voltage oscillations, while still exhibiting a stable behavior.