1. Introduction

The main part of electric energy in urban and industrial power supply systems is distributed to consumers through 6–10 kV cable networks with an isolated neutral. They usually have a complex structure that depends on the location and number of power sources, switchgears, and power consumers [

1,

2,

3,

4], as well as manufacturing technology and the presence of large consumers. Communication lines play a significant role in such cable networks [

5,

6,

7,

8]. They are used to redistribute electric power between power sources and switchgears over a city or industrial enterprise [

9,

10,

11]. The power transmitted through a cable line can attain 5–70 mVA. To transmit this power, a power line is usually made in the form of a bunch of several cables with core cross sections of 70–240 mm

2.

Single-phase ground faults (SGFs) are among the main faults [

12,

13,

14,

15] in cable lines with isolated neutral; their percentage is at least 75–90% of the total number of electrical faults [

16]. Single-cable lines are usually protected against SGFs [

12,

13,

14,

15] with the use of a device based on measuring SGF current. SGF current is measured with a zero current transformer (ZCT) at the beginning of a line. A feed-through ZCT with a ring core with the secondary winding wound on is typically used for these purposes. To ensure selectivity, this protection device should be offset from zero-sequence currents during SGFs in buses of a substation, which significantly limits the protection sensitivity. In addition, this protection device has relative selectivity [

12,

13], since it protects not only a cable line against SGFs but also its full load.

The sensitivity of SGF protections can be enhanced by using an additional residual directional relay. This eliminates the need to offset the protection from the intrinsic current of a protected line [

12,

13,

14,

15] and its load. However, this protection is also relatively selective [

12,

13].

If a line is made as a bunch of two cables, then the line protection uses one ZCT, which is put simultaneously on both cables, or one ZCT per cable. In the latter case, the secondary windings of the ZCT are parallel or series-aiding connected. The design of this protection and its disadvantages are similar to the protection of a single-cable line [

12]. If there are more cables in a bunch, then ZCTs are mounted on all cables, and their secondary windings are series-aiding or parallel-connected. Mixed connections of windings are recommended for certain protection types [

12,

16].

Selective disconnection of a damaged network element is a fundamental requirement for SGF relay protection systems in 6–10-kV cable networks. Therefore, two-directional zero-sequence overcurrent protections with a stepwise selection of response time of ZZP-1 or MiCOM type are mounted in each communication line. These protections are relatively selective; a zero-sequence voltage source is required to ensure their operation. In relay protection, this voltage is derived from the open-delta connected secondary winding of a three-phase measuring voltage transformer [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In addition, these protections are incapable of detecting a cable where an SGF occurred in bunched cable lines.

Since the number of connections at communication line buses permanently changes in a network, the calculation of directional current protection thresholds is quite complex and depends on many factors. Therefore, it is not always possible to configure these protections so that they properly respond to SGFs in a network with such a line. In addition, a failure of the protection during one of the stages can lead to a long and labor-intensive search for the cause of the protected line break. Moreover, in a complex network, the search time can exceed two hours, as determined by the requirement for electrical installations. In addition, in the case where an SGF occurs in a bunched cable line, additional time is required after the protection operation for detecting a damaged cable in this bunch.

The above disadvantages can be avoided by using absolutely selective protections capable of automatically detecting a damaged cable.

Thus, the design of new, absolutely selective SPG protection devices capable of detecting a damaged cable is relevant.

The structure of this paper is as follows.

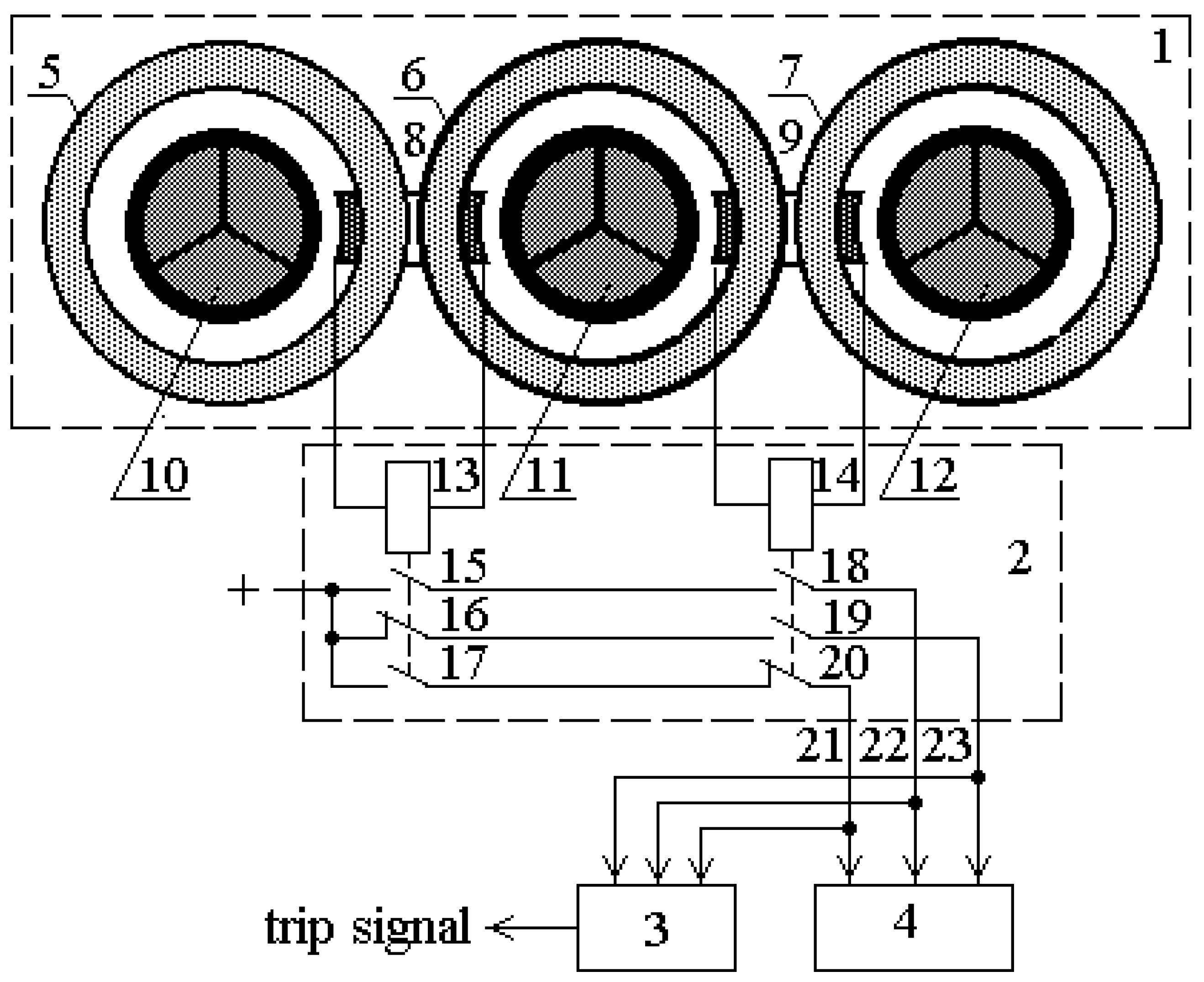

Section 2 is devoted to the design of an absolutely selective SGF protection for a two-cable bunched line, which is capable of detecting a damaged cable in this line. Protection devices and techniques for calculating fault currents in the cables depending on the fault location are described, and currents in the measuring elements of the protection and dead zone size are determined in this section.

Section 3 considers features of the protection design for a line in the form of a bunch of more than two cables, simulates fault currents in the cables of this line, and analyzes the operation of the measuring element of the protection.

Section 4 describes the results of our work and discusses them. Final

Section 5 provides the conclusions drawn during this work.

2. Protection of Two-Cable Lines

To ensure absolute selectivity of the SGF protection system of a line consisting of two cables and its capability of automatically detecting a damaged cable, we suggest the protection technique where SGF currents in these cables are compared [

17,

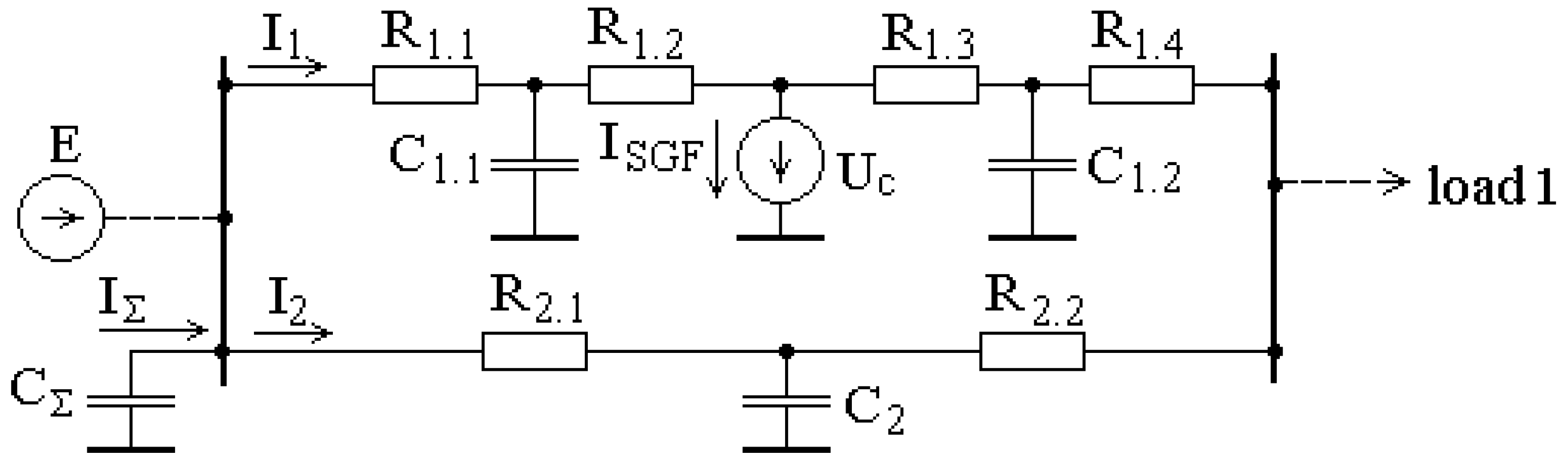

18]. The protection circuit with the use of this technique is shown in

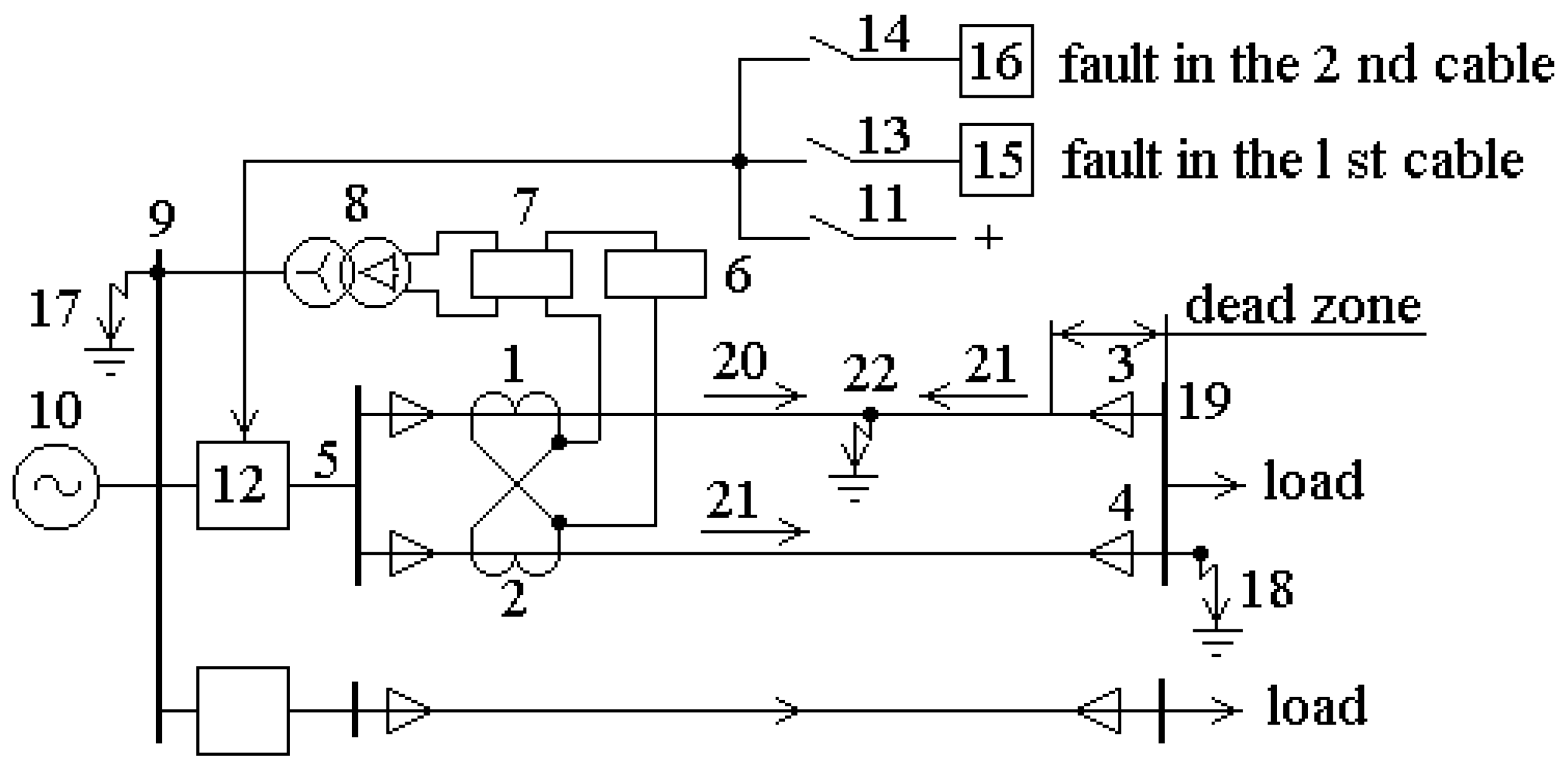

Figure 1. Here, series-opposing secondary windings 1 and 2 of a ZCT at cables 3 and 4 of protected line 5 are connected to serially connected current windings of RT-40/02 current relay 6 [

8,

9,

16] and power-directional relay 7. The voltage winding of power-directional relay 7 is connected to buses 9 of power source 10 through measuring voltage transformer 8. In this protection circuit, the power-directional relay is intended to detect a damaged cable upon SGFs in this line.

Normally open contact 11 of current relay 6 is connected to the trip circuit of breaker 12 and to signal relays 15 and 16 through normally open contacts 13 and 14 of the left and right end positions of power-directional relay 7.

Since the cables in protected line 5 are similar, then zero-sequence currents 20 and 21 flowing through the ZCT in these cables are equal in magnitude in the event of a ground fault at points 17 or 18 at buses 9 and 19 of the substation and load. As a result, the difference between the currents in secondary windings 1 and 2 of the ZCT and the current in the current windings of current relay 6 and power-directional relay 7 is zero.

In the case of an SGF in any of cables 3 and 4 of this line between the ZST and load bus 19, e.g., at point 22, zero-sequence currents 20 and 21 flowing through the ZST in cables 3 and 4 of the line are not equal in magnitude. Therefore, the difference between currents in secondary windings 1 and 2 of the ZST and, hence, the current in the current windings of current relay 6 and power-directional relay 7 are nonzero.

Figure 1 shows that the current in the current windings of current relay 6 and power-directional relay 7 is maximal if an SGF occurs at point 22 at the beginning of cable 3, that is, immediately after the ZST, and this current is zero in the case of an SGF in buses 9 and 19. Since the operating current of current relay 6 I

op ≠ 0, the protection that uses this technique has a dead zone on the side of load bus 19. The protection operating current I

op depends on the difference in the parameters of cables in the bunch and ZST measurement errors. In turn, the size of the dead zone depends on the operating current I

op of the fault detector of the protection and the total capacity C

∑ of all connections to the substation bus 9 with respect to ground, except for protected line 5.

The length of the protection dead zone is estimated by the dependence of currents 20 and 21 on SGF point 22 at different C

∑ values. However, it is difficult to derive these dependencies because all known techniques [

19,

20,

21,

22] calculate SGF currents in single-cable lines.

Hence, the zero-sequence currents

and

in cables 3 and 4 (currents 20 and 21 in

Figure 1) are suggested to be calculated using the simplified circuit shown in

Figure 2. This circuit is obtained from an equivalent-T cable circuit [

23] under the following assumptions:

The active resistance of the cable insulation with respect to the ground is high, and the leakage current is small in an undamaged cable; hence, they can be neglected, and the SGF current calculation error does not exceed 0.5–1.0%;

Taking into account data in

Table 1 [

24], the inductive resistances X

0 of cable lines can also be neglected, since they are significantly lower than the active resistance R

0. In this case, the error in SGF currents is 3–10%.

Figure 2.

Simplified circuit for calculating zero-sequence currents in a two-cable line.

Figure 2.

Simplified circuit for calculating zero-sequence currents in a two-cable line.

In the circuit in

Figure 2, R

1.1–R

1.4 are the active resistances and C

1.1 and C

1.2 are phase capacitances with respect to the ground of the segments of a damaged cable of a two-cable line; R

2.1 and R

2.2 are the active resistances and C

2.2 is the phase capacitance with respect to the ground of the safe cable; I

SGF is the SGF current at point 22, and I

∑ is the total zero-sequence current of all connections.

When detecting an SGF, the difference in the zero-sequence currents in the damaged and safe cables is as follows:

The elements of this circuit are found as follows. This line is usually made from two identical cables. Therefore, the active resistances and capacitance of the damaged cable are calculated as follows:

where l

c and l

SGF are the cable length and the distance from its beginning to SGF point 22; R

0 and C

0 are the active resistance and phase capacitance of the cable with respect to the ground per kilometer of its length.

The active resistances and the capacitance of the safe cable of

Since other lines of a network are made from N cables of different types and lengths, the total capacitance of all connections except for line 5 is defined as

where l

cn is the length of the nth cable; C

0n is the phase capacitance with respect to the ground of the nth cable per kilometer of its length. The voltage U

c in the calculation circuit is set equal to the voltage of the damaged phase of a cable with respect to the ground.

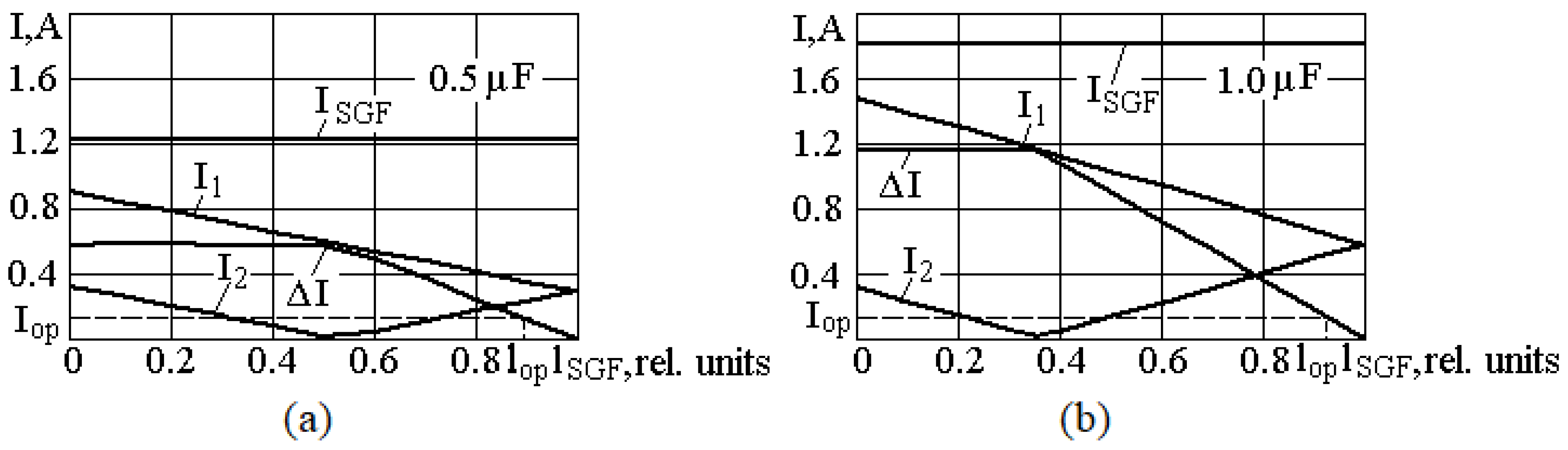

It is quite difficult to derive analytical expressions for the dependencies

and

even with the use of the simplified calculation circuit in

Figure 2. However, these dependencies can be calculated for different capacitance values with the use of the well-known and quite simple circuit simulation software Electronics Workbench Version 5.12 (25 February 2024) [

25]. Zero-sequence currents in a line of two cables of 6 kV in voltage were calculated based on data from

Table 1 for an Al cable of 25 mm

2 in cross section and 1 km in length with the capacitance C

∑ = 0.5 and 1.0 μF. The results are shown in

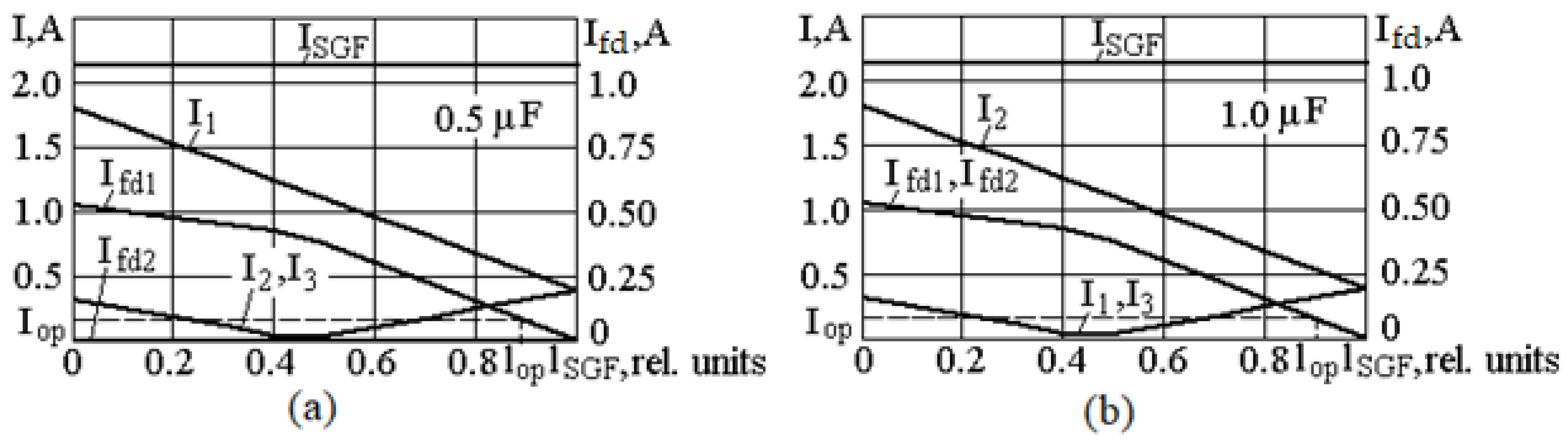

Figure 3a,b.

If the minimal protection operation current I

op is known, then the dead zone boundary lop can be easily found from the dependence

and I

op, as shown in

Figure 3. These figures clearly show that the dead zone length depends on the total capacitance C

∑ of the connections to substation buses, and an increase in C

∑ reduces this zone.

The protection operation current I

op depends on the imbalance current I

imb caused by the difference in the parameters of cables in the bunch of the protected line and the ZCT measurement errors:

where k

off = 1.2–1.25 is the safety factor.

The easiest way of determining the imbalance current I

imb is experimental by connecting all connections to the protected line 5. I

imb can also be calculated based on the total error of current transformers of the protection, which is about 10%, according to [

8,

9].

If an SGF occurs in a bunched cable line and a protection system operates, a damaged cable is detected by the direction of current in the current winding circuit of power-directional relay 7. For example, if the current in the winding of current relay 6 and the current winding of power-directional relay 7 exceeds the protection operation current Iop upon an SGF in cable 3 of power transmission line 5, then current relay 6 actuates, its normally open contact 11 closes, and it disconnects power transmission line 5 from common buses 9 with the help of breaker 12. In this case, the direction of current in the current winding of power-directional relay 7 is such that it closes its normally open contact 13 and actuates signal relay 15. Actuation of this signal relay indicates the occurrence of an SGF in cable 3. If an SGF occurs in cable 4, then the current in the current winding of relay 7 changes direction and closes normally open contact 14 of power-directional relay 7 and actuates signal relay 16. Actuation of this signal relay indicates the occurrence of an SGF in cable 4.

Since this protection has a dead zone ldz, a similar protection system should be mounted at the end of a protected line to cover the dead zone. This enables supporting the reliability of the protection under non-ideal operating conditions upon possible fluctuations ΔI under actual operating conditions, including resistance to failures or parameter drifts.

In 2006, an absolutely selective protection system against single-phase ground faults in bunched cable lines was mounted at the Aksu Ferroalloy Plant in the communication line between the main switchgear (MSG-10) of the main step-down substation (SDS-1) and switchgear SG-1. No false operation of this protection was reported by the maintenance personnel.

As a result, the protection of this line is absolutely selective, has no dead zone, and is capable of detecting a cable where an SGF has occurred.

4. Results and Discussion

Electrical power supply of cities and large enterprises is almost always performed through 6–10 kV cable networks with an isolated neutral. In such networks, power transmission lines to large consumers are made as bunched cables. Most faults in such cables are single-phase ground faults. In practice, widely known simple and directional protections are used to protect against them. Their operation is based on measuring zero-sequence currents in a line; therefore, these protections are relatively selective and can improperly respond to zero-sequence currents in a network. In addition, they cannot detect a cable with SGF in the bunch of a damaged line. These disadvantages can be eliminated by using simple protections for bunched cable lines where the difference in zero-sequence currents in these cables is measured to ensure their absolute selectivity, and their direction is measured to determine a damaged cable in the bunch. These protections are essentially new. Therefore, theoretical foundations are required for their design and the justification of the operation of such protections. As a result of the development of these theoretical foundations, the following results have been obtained.

A technique for protecting a line of two cables against SGFs in a network with an isolated neutral is developed. It is based on measuring the difference in the magnitudes of zero-sequence currents in these cables and makes it possible to design absolutely selective protections in contrast to known ones. These protections are almost the only ones capable of providing absolute selectivity without the use of a zero-sequence voltage transformer. This enables protecting complex multi-stage lines against SGFs, which cannot always be ensured by known protection systems.

One of the main disadvantages of the known protections of two-cable lines against single-phase ground faults is their incapability of detecting a damaged cable. Hence, after tripping a damaged line, service personnel should perform a number of complex and labor-intensive engineering and organizational measures for detecting a damaged cable. The suggested technique for detecting a cable damaged during an SGF in a two-cable line is based on measuring the direction of the current in the current windings of the fault detector relay caused by the difference in the values of the zero-sequence currents in the two cables. The SGF protection systems that use this technique are currently almost the only quite simple and cheap systems capable of near instantaneously and reliably detecting a damaged cable in such lines.

Parameters of the protection of a bunched cable line are estimated from the dependence of zero-sequence current in each cable of this bunch on the SGF point in one of them. A simple and quite accurate method is suggested for their calculation with the use of the widely known and fairly simple circuit simulation software Electronics Workbench. The calculations by this method have shown that the protection suggested for a line of several cables has a dead zone. The length of this zone depends on the fault detector operation threshold, the protected line length, and the total capacitance of all connections at substation buses with respect to the ground. To eliminate the dead zone, a similar protection should be mounted at the end of a protected line.

The further improvement of real protection systems for bunched cable lines could consist of refusal to use electromechanical power directional relays, which consume a significant amount of electricity and require a zero-sequence voltage source for operation. In addition, this refusal can reduce the protection dead zone.