Review of Virtual Inertia Based on Synchronous Generator Characteristic Emulation in Renewable Energy-Dominated Power Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

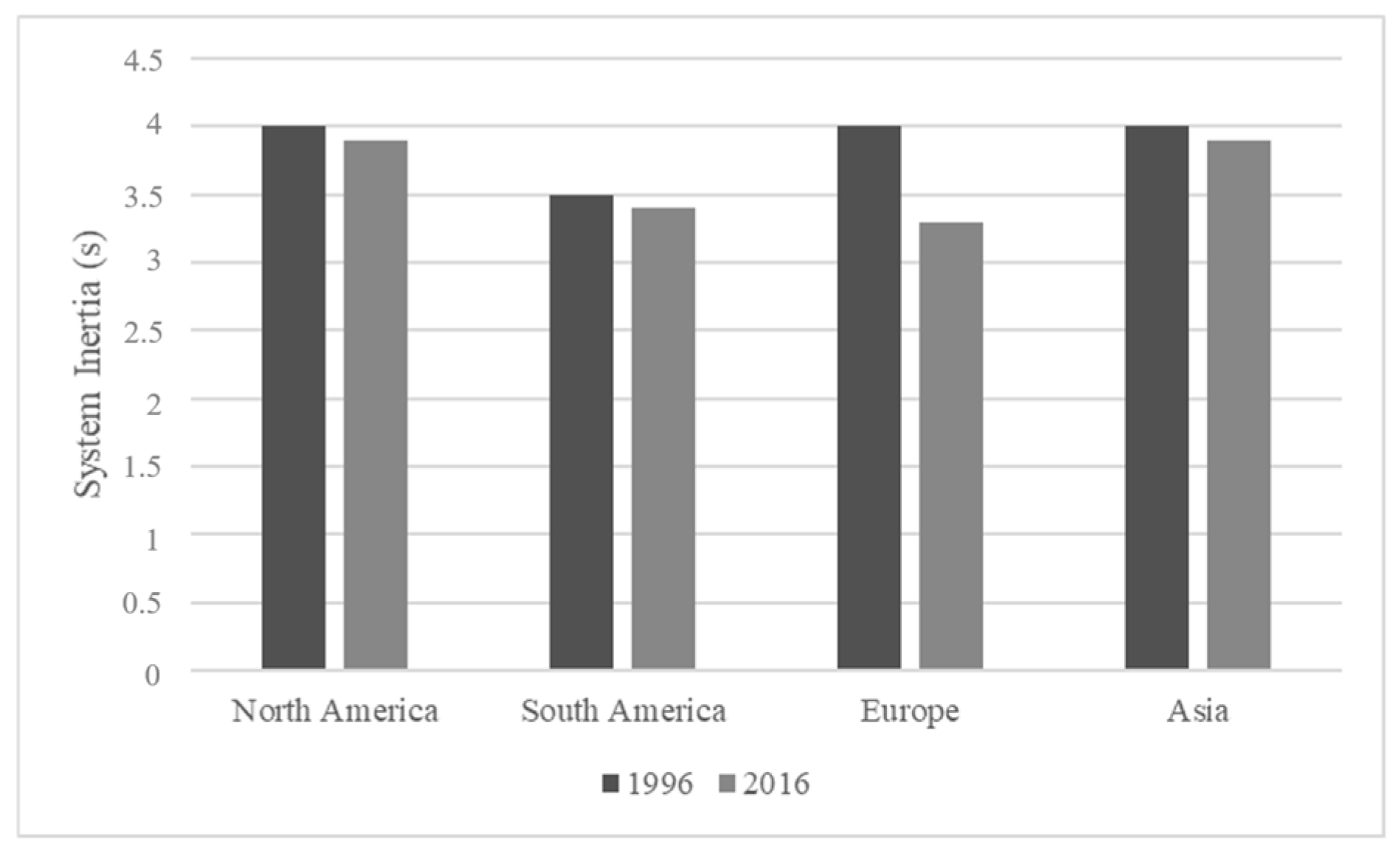

2. Effect of High Renewable Energy Penetration on System Stability

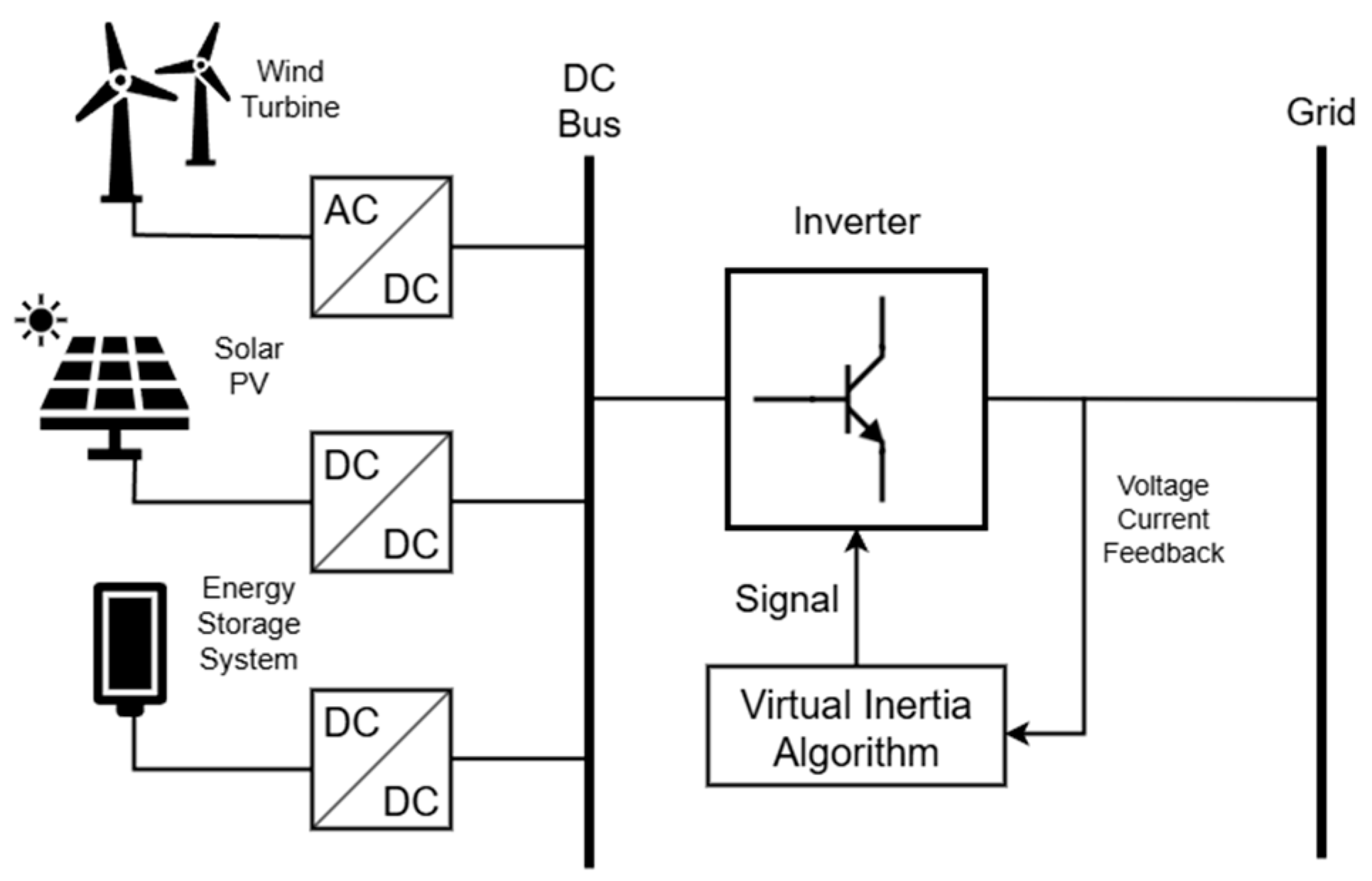

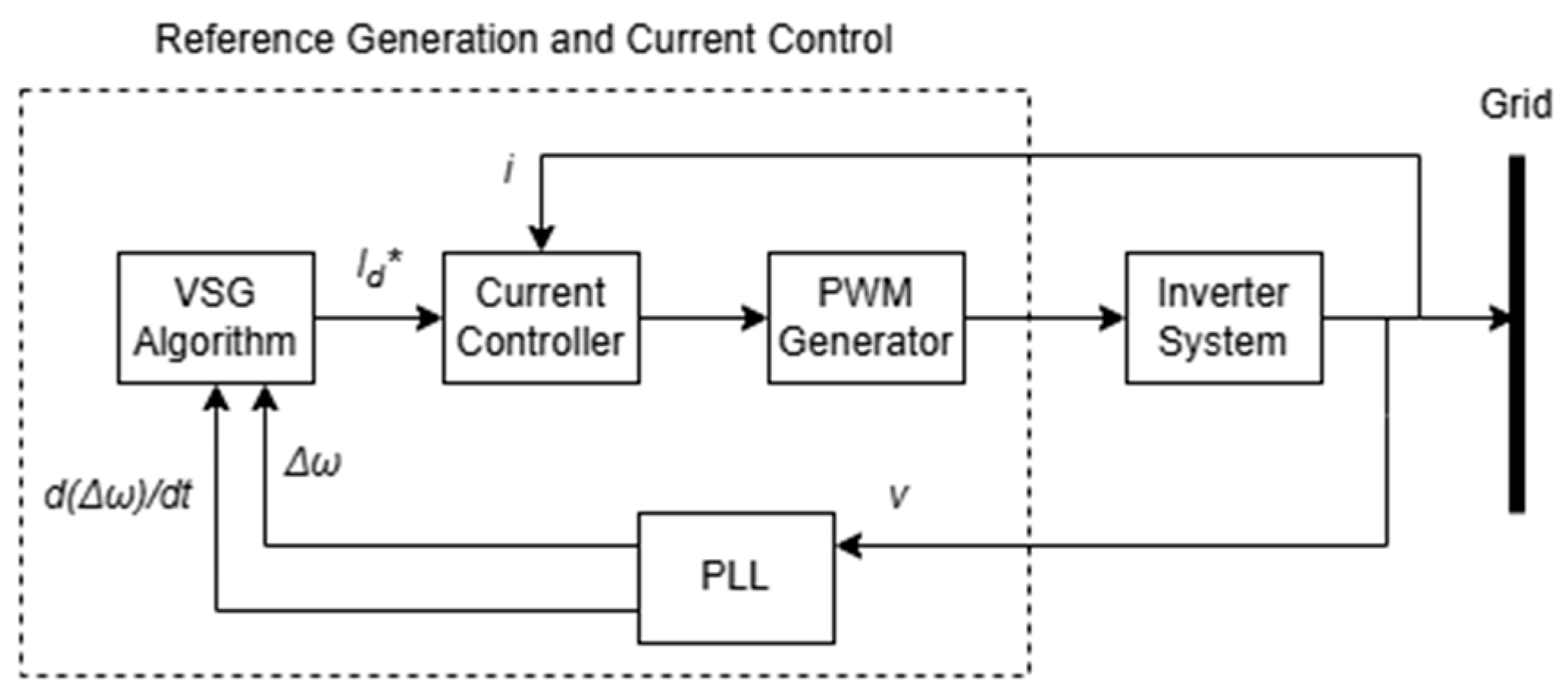

3. Virtual Inertia Applications in Power Systems

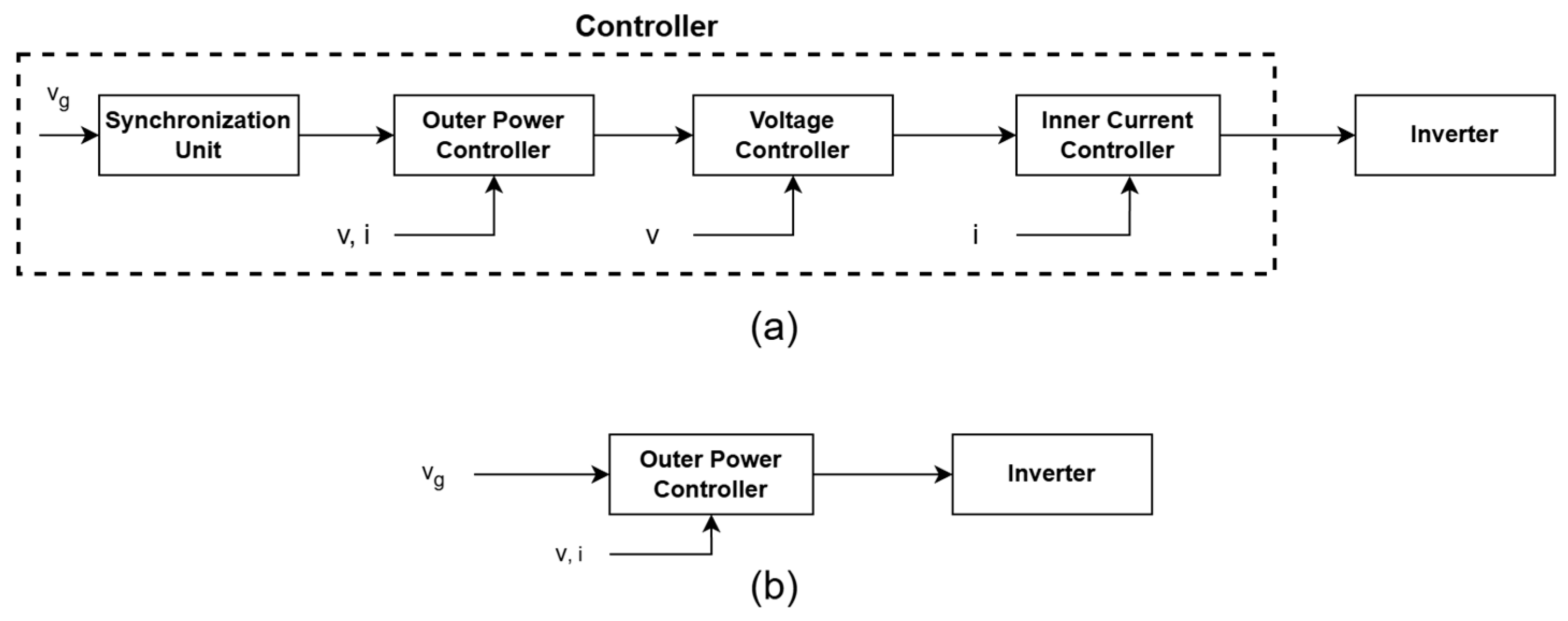

4. Virtual Inertia Methods

4.1. Droop Control

4.2. Synchronverter

4.3. Virtual Synchronous Generator (VSG)

4.4. Swing Equation-Based Model

4.5. Data-Driven Grid-Forming Methods

5. Method Comparison

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Alternating Current |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DG | Distributed Generation |

| ENTSO-E | The European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity |

| ERCOT | The Electric Reliability Council of Texas, Inc. |

| GFL | Grid-Following |

| GFM | Grid-Forming |

| IR | Inertial Response |

| NZE | Net-Zero Emissions |

| PFR | Primary Frequency Response |

| PLL | Phase-Locked Loop |

| PLN | Perusahaan Listrik Negara (State Electricity Company) |

| PV | Photovoltaics |

| PWM | Pulse Width Modulation |

| RoCoF | Rate of Change of Frequency |

| RUPTL | Rencana Usaha Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik (Electricity Supply Business Plan) |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| VSG | Virtual Synchronous Generator |

| VSWT | Variable-Speed Wind Turbine |

References

- Guerrero, J.M.; Blaabjerg, F.; Zhelev, T.; Hemmes, K.; Monmasson, E.; Jemei, S.; Comech, M.P.; Granadino, R.; Frau, J.I. Distributed Generation: Toward a New Energy Paradigm. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2010, 4, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement—Publication. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/184656 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- UNFCCC. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, V.; Chung, C. Renewable energy for SDG-7 and sustainable electrical production, integration, industrial application, and globalization: Review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 15, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.-C.; Nguyen, P.-L.; Ma, Z.; Sheng, W. Self-Synchronized Synchronverters: Inverters Without a Dedicated Synchronization Unit. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.V.; Visscher, K.; Diaz, J.; Karapanos, V.; Woyte, A.; Albu, M.; Bozelie, J.; Loix, T.; Federenciuc, D. Virtual synchronous generator: An element of future grids. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT Europe), Gothenburg, Sweden, 11–13 October 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tamrakar, U.; Shrestha, D.; Maharjan, M.; Bhattarai, B.P.; Hansen, T.M.; Tonkoski, R. Virtual Inertia: Current Trends and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, W.; Duc, N.H.; Ruiz, D.G.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Van, N.N. Smart Energy Buildings: PV Integration and Grid Sensitivity for the Case of Vietnam. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems, Online, 27–29 April 2022; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Poolla, B.K.; Bolognani, S.; Dorfler, F. Optimal Placement of Virtual Inertia in Power Grids. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2017, 62, 6209–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vyver, J.; De Kooning, J.D.M.; Meersman, B.; Vandevelde, L.; Vandoorn, T.L. Droop Control as an Alternative Inertial Response Strategy for the Synthetic Inertia on Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiesen, H.; Jauch, C.; Gloe, A. Design of a System Substituting Today’s Inherent Inertia in the European Continental Synchronous Area. Energies 2016, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (KESDM). Peraturan Menteri Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Nomor 20 Tahun 2020 tentang Aturan Jaringan Sistem Tenaga Listrik (Grid Code). Indonesia: BN 2020/NO 1794; JDIH ESDM.GO.ID: 8 HLM. 2020. Available online: https://jdih.esdm.go.id/dokumen/view?id=2120 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Khan, M.; Wu, W.; Li, L. Grid-forming control for inverter-based resources in power systems: A review on its operation, system stability, and prospective. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndirangu, J.G.; Nderu, J.N.; Muhia, A.M.; Maina, C.M. Power quality challenges and mitigation measures in grid integration of wind energy conversion systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Energy Conference (ENERGYCON), Limassol, Cyprus, 3–7 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, Z. Revolution of frequency regulation in the converter-dominated power system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 111, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, J. Synchronisation methods for grid-connected voltage source converters. IEE Proc. Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2001, 148, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.-P.; Hesse, R. Virtual synchronous machine. In Proceedings of the 2007 9th International Conference on Electrical Power Quality and Utilisation, Barcelona, Spain, 9–11 October 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulos, G.C.; Zhong, Q.-C.; Ming, W.-L. PLL-Less Nonlinear Current-Limiting Controller for Single-Phase Grid-Tied Inverters: Design, Stability Analysis, and Operation Under Grid Faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 5582–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Miura, Y.; Ise, T. Comparison of dynamic characteristics between virtual synchronous generator and droop control in inverter-based distributed generators. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 3600–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; China Electric Power Research Institute; Liu, K.; Chen, L. A novel frequency-changer control strategy based on a virtual synchronous motor. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 5, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashabani, M.; Freijedo, F.D.; Golestan, S.; Guerrero, J.M. Inducverters: PLL-Less Converters with Auto-Synchronization and Emulated Inertia Capability. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 7, 1660–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnefors, L.; Hinkkanen, M.; Riaz, U.; Rahman, F.M.M.; Zhang, L. Robust Analytic Design of Power-Synchronization Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 5810–5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Rygg, A.; Molinas, M. Self-Synchronization of Wind Farm in an MMC-Based HVDC System: A Stability Investigation. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2017, 32, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, S.; Tironi, E.; Danna, D.S. Integrated control strategy for islanded operation in smart grids: Virtual inertia and ancillary services. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2017 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Milan, Italy, 6–9 June 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Askarian, I.; Eren, S.; Pahlevani, M.; Knight, A.M. Digital Real-Time Harmonic Estimator for Power Converters in Future Micro-Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 6398–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PT PLN (Persero). Rencana Usaha Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik (RUPTL) 2021–2030. 2021. Available online: https://gatrik.esdm.go.id/assets/uploads/download_index/files/376d5-paparan-pln-bapak-murtaqi-.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guillamón, A.; Gómez-Lázaro, E.; Muljadi, E.; Molina-García, Á. Power systems with high renewable energy sources: A review of inertia and frequency control strategies over time. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 109369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zhang, X. VSG-Based Dynamic Frequency Support Control for Autonomous PV–Diesel Microgrids. Energies 2018, 11, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Wang, P.; Guerrero, J.M. Improvement of Frequency Regulation in VSG-Based AC Microgrid Via Adaptive Virtual Inertia. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Y.R.; Trentini, R.; Kutzner, R. Control strategy for Inertia Emulation through Grid-Following Inverters. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Conference on Systems and Control (ICSC), Caen, France, 24–26 November 2021; pp. 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Golestan, S.; Monfared, M.; Freijedo, F.D.; Guerrero, J.M. Performance Improvement of a Prefiltered Synchronous-Reference-Frame PLL by Using a PID-Type Loop Filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 3469–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poolla, B.K.; Gros, D.; Dorfler, F. Placement and Implementation of Grid-Forming and Grid-Following Virtual Inertia and Fast Frequency Response. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 3035–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Seo, K.; Park, J.-W.; Lee, K.Y. New frequency stability assessment based on contribution rates of wind power plants. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 164, 110388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.-C.; Weiss, G. Synchronverters: Inverters that mimic synchronous generators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, H.; Monfared, M.; Fazeli, M.; Golestan, S. Single-phase Grid-forming Inverters: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computing, Electronics & Communications Engineering (iCCECE), Swansea, UK, 14–16 August 2023; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sekizaki, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Yorino, N.; Zoka, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Nishizaki, I. A development of a single-phase synchronous inverter for grid resilience and stabilization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Asia (ISGT-Asia), Auckland, New Zealand, 4–7 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, X.-D.; Zhong, Y.-R.; Matsui, M.; Ren, B.-Y. Analysis and Design of a Digital Phase-Locked Loop for Single-Phase Grid-Connected Power Conversion Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 3581–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Saleem, M.I.; Roy, T.K.; Oo, A.M.T. Virtual Inertia Planning for Enhancing Grid Stability in Low-Inertia Systems. IET Energy Syst. Integr. 2025, 7, 70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffal, H.; Guanetti, L.; Rancilio, G.; Spiller, M.; Bovera, F.; Merlo, M. Battery Energy Storage System Performance in Providing Various Electricity Market Services. Batteries 2024, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Peng, Q.; Liu, T.; Meng, J.; Zeng, X.; Chen, G. Coordinated Virtual Inertia Control of Grid-Connected Photovoltaic-Battery Energy Storage System Considering Power Reserve and Fluctuation Smoothing. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 14th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Shanghai, China, 9–12 June 2023; pp. 428–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jana, S.K.; Srinivas, S. Single Phase Solar Inverter with Inertia Emulation. In Proceedings of the 2018 8th IEEE India International Conference on Power Electronics (IICPE), Jaipur, India, 13–15 December 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zografos, D.; Ghandhari, M.; Eriksson, R. Power system inertia estimation: Utilization of frequency and voltage response after a disturbance. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2018, 161, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C.; Matas, J.; de Vicuna, L.G.; Castilla, M. Hierarchical Control of Droop-Controlled AC and DC Microgrids—A General Approach Toward Standardization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandorkar, M.C.; Divan, D.M.; Adapa, R. Control of parallel connected inverters in standalone AC supply systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1993, 29, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F. Droop Control Optimization Strategy for Parallel Inverters in a Microgrid Based on an Improved Population Division Fruit Fly Algorithm. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 24877–24894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M.; Luna, A.; Rodriguez, P.; Teodorescu, R. Adaptive Droop Control Applied to Voltage-Source Inverters Operating in Grid-Connected and Islanded Modes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 4088–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Lagoa, C.M.; Chaudhuri, N.R. Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for Droop-Based Grid Forming Converters Providing Fast Frequency Support. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 39, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Chen, Z.; Schneider, K.P.; Lasseter, R.H.; Nandanoori, S.P.; Tuffner, F.K.; Kundu, S. A Comparative Study of Two Widely Used Grid-Forming Droop Controls on Microgrid Small-Signal Stability. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.; Udawatte, H.; Zhou, W.; Hill, D.J.; Bahrani, B. Grid-Forming Inverters: A Comparative Study of Different Control Strategies in Frequency and Time Domains. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2024, 5, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.-C. Virtual Synchronous Machines: A unified interface for grid integration. IEEE Power Electron. Mag. 2016, 3, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P.S. Power System Stability and Control; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Piya, P.; Karimi-Ghartemani, M. A stability analysis and efficiency improvement of synchronverter. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Long Beach, CA, USA, 20–24 March 2016; pp. 3165–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, T.; Zheng, T.Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Parameter design and hot seamless transfer of single-phase synchronverter. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2018, 160, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Harnefors, L.; Nee, H.-P. Power-Synchronization Control of Grid-Connected Voltage-Source Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2010, 25, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Yuan, X. Virtual Synchronous Control for Grid-Connected DFIG-Based Wind Turbines. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2015, 3, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhong, Q.-C.; Yan, J.D. Synchronverter-based control strategies for three-phase PWM rectifiers. In Proceedings of the 2012 7th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Singapore, 18–20 July 2012; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kryonidis, G.C.; Malamaki, K.-N.D.; Mauricio, J.M.; Demoulias, C.S. A new perspective on the synchronverter model. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 140, 108072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Miura, Y.; Bevrani, H.; Ise, T. Enhanced Virtual Synchronous Generator Control for Parallel Inverters in Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 2268–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Gharehpetian, G.B.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. On the Role of Virtual Inertia Units in Modern Power Systems: A Review of Control Strategies, Applications and Recent Developments. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 159, 110067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D.; Tamrakar, U.; Ni, Z.; Tonkoski, R. Experimental verification of virtual inertia in diesel generator based microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–25 March 2017; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tamrakar, U.; Tonkoski, R.; Ni, Z.; Hansen, T.M.; Tamrakar, I. Current control techniques for applications in virtual synchronous machines. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 6th International Conference on Power Systems (ICPS), New Delhi, India, 4–6 March 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.; Saha, T.K.; Modi, N.; Masood, N.-A.; Mosadeghy, M. The combined effects of high penetration of wind and PV on power system frequency response. Appl. Energy 2015, 145, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cantarellas, A.M.; Rocabert, J.; Luna, A.; Rodriguez, P. Synchronous Power Controller with Flexible Droop Characteristics for Renewable Power Generation Systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2016, 7, 1572–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, I.; Kabalci, E.; Bayindir, R. Review of multilevel voltage source inverter topologies and control schemes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, Y.; Han, H.; Fu, S.; Luo, S.; Shi, G. A Modified VSG Control Scheme with Virtual Resistance to Enhance Both Small-Signal Stability and Transient Synchronization Stability. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 6005–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Analysis and Design of a Modified Virtual Synchronous Generator Control Strategy for Single-phase Inverter Application. In Proceedings of the 2020 23rd International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Hamamatsu, Japan, 24–27 November 2020; pp. 432–437. [Google Scholar]

- Sakimoto, K.; Miura, Y.; Ise, T. Stabilization of a Power System Including Inverter-Type Distributed Generators by a Virtual Synchronous Generator. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2014, 187, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipoor, J.; Miura, Y.; Ise, T. Power System Stabilization Using Virtual Synchronous Generator with Alternating Moment of Inertia. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2015, 3, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirase, Y.; Abe, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Sakimoto, K.; Bevrani, H.; Ise, T. A novel control approach for virtual synchronous generators to suppress frequency and voltage fluctuations in microgrids. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, V.; Weiss, G. Synchronverters with Better Stability Due to Virtual Inductors, Virtual Capacitors, and Anti-Windup. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 5994–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, V.; Lazaro, A.; Barrado, A.; Zumel, P.; Fernandez, C.; Sanz, M. Black-box modeling of three phase voltage source inverters based on transient response analysis. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition—APEC 2010, Palm Springs, CA, USA, 21–25 February 2010; pp. 1279–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Guruwacharya, N.; Bhandari, H.; Subedi, S.; Vasquez-Plaza, J.D.; Stoel, M.L.; Tamrakar, U.; Wilches-Bernal, F.; Andrade, F.; Hansen, T.M.; Tonkoski, R. Data-driven Modeling of Commercial Photovoltaic Inverter Dynamics Using Power Hardware-in-the-Loop. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM), Sorrento, Italy, 22–24 June 2022; pp. 924–929. [Google Scholar]

- Guruwacharya, N.; Chakraborty, S.; Saraswat, G.; Bryce, R.; Hansen, T.M.; Tonkoski, R. Data-Driven Modeling of Grid-Forming Inverter Dynamics Using Power Hardware-in-the-Loop Experimentation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 52267–52281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.-H.; Lin, F.-J.; Shih, C.-M.; Kuo, C.-N. Intelligent Control of Microgrid with Virtual Inertia Using Recurrent Probabilistic Wavelet Fuzzy Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 35, 7451–7464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, H.; He, H. Energy-Storage-Based Intelligent Frequency Control of Microgrid with Stochastic Model Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Features | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|

| Droop Control |

|

|

| Synchronverter |

|

|

| VSG |

|

|

| Swing-Equation-Based Method |

|

|

| Data-Driven Grid Forming |

|

|

| Method | Minimum Frequency (Hz) | Maximum RoCoF (Hz/s) | Settling Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Virtual Inertia | 57.3 | 1.9 | 11.3 |

| Synchronverter | 58.1 | 1.5 | 13.2 |

| Ise Lab | 58.6 | 1.6 | 17.7 |

| VSG | 58.3 | 1.7 | 17.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waskito, F.; Wijaya, F.D.; Firmansyah, E. Review of Virtual Inertia Based on Synchronous Generator Characteristic Emulation in Renewable Energy-Dominated Power Systems. Electricity 2025, 6, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/electricity6040069

Waskito F, Wijaya FD, Firmansyah E. Review of Virtual Inertia Based on Synchronous Generator Characteristic Emulation in Renewable Energy-Dominated Power Systems. Electricity. 2025; 6(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/electricity6040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaskito, Fikri, F. Danang Wijaya, and Eka Firmansyah. 2025. "Review of Virtual Inertia Based on Synchronous Generator Characteristic Emulation in Renewable Energy-Dominated Power Systems" Electricity 6, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/electricity6040069

APA StyleWaskito, F., Wijaya, F. D., & Firmansyah, E. (2025). Review of Virtual Inertia Based on Synchronous Generator Characteristic Emulation in Renewable Energy-Dominated Power Systems. Electricity, 6(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/electricity6040069