Abstract

With the transition towards more sustainable paint formulations that are waterborne, the susceptibility to microbial contamination has to be better controlled to increase shelf life and functional lifetime. However, recent restrictions in European regulations on the use of biocides have put limitations on the concentrations for traditional systems providing either in-can or dry-film preservation. The commercial technologies for in-can preservation that are currently available are based on isothiazolines, such as 2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one (MIT), 1,2-benzisothiazolin-3-one (BIT) and 5-chloro-2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one (CMIT). At present, however, only a limited number of alternatives can be used and are reviewed in this presentation. Examples of non-sensitizing biocidal components for coatings include quaternary/cationic nitrogen amines, silver ions and zinc complexes. However, the use of the latter is not without risk to human health. Therefore, it is believed that disruptive methods will need to be implemented in parallel with more innovative bio-inspired solutions. In particular, the antimicrobial polymers, amino-acid-based systems and peptides have similar functions in nature and can offer antimicrobial activities. Additionally, cross-border solutions currently applied in food or cosmetics industries should be considered as examples that need to be further adapted for paint formulations. However, incorporation in paint formulations remains a challenge in view of the stabilization and rheology control needed for paint. This work’s overview aims to provide different strategies and best evidence for future trends.

1. Introduction

Waterborne paint formulations have been introduced in response to demands for more eco-friendly solutions with fewer or no chemical solvents and lower VOC emissions. In parallel, however, such aqueous environments are beneficial for the growth and survival of micro-organisms such as bacteria, fungi and yeast. They can get into paint via the raw materials or various contamination sources in the processing plant. In a particular study, microbial contamination of the paint with Pseudomonas as the predominant genus mainly occurred as a result of biofilm formation in the production equipment [1]. In another study, sufficient screening and appropriate selection of the raw materials was advised in order to reduce contamination [2]. The degradation of paints in the presence of micro-organisms can be noticed by a change in color, a penetrating odor, gas formation, reduced stability, a pH variation and a viscosity reduction. The quality loss of tainted paint finally results in product spoilage and time delay. Although the presence of bacteria can be controlled through better material selection and plant hygiene, they cannot be fully avoided. Therefore, in-can preservation (PT-6) is required to ensure a long in-pot lifetime, which is industrially expected to be at least 3 years.

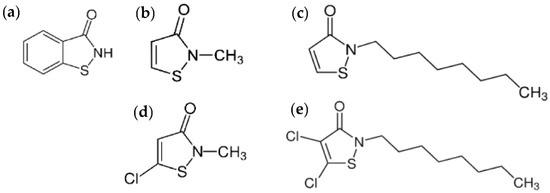

The use of biocides for in-can preservation (PT-6), which are inherently toxic and potentially affect human health, has been subjected to more stringent legislation in recent years, following the Biocidal Products Regulation (updated March 2020). In the early years, organo-mercury compounds and formaldehyde biocides were banned because of carcinogenic effects. Following risk assessment studies, the diverse range and different potential of formaldehyde-condensate compounds in regard to formaldehyde gas were recognized and taken into account for preservatives. While some standards for paints and coatings (Green Seal GS-11) prohibit the release of free formaldehyde, others have restricted the emission of free formaldehyde at below 100 ppm. Isothiazolinone derivatives were introduced as formaldehyde-free alternatives for both in-can and dry-film preservation, including 1,2-benzisothiazolin-3-one (BIT), 2-methylisothiazol-3(2H)-one (MIT), 2-octyl-2H-isothiazol-3-one (OIT), 5-chloro-2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one (CMIT) and 4,5-dichloro-2-n-octyl-3(2H)-isothiazolone (DCOIT) (Figure 1) [3]. Nevertheless, the observations of allergic skin reactions towards one specific type of isothiazoline, i.e., MIT, lead to its classification as skin sensitizer and a reduction in its allowable concentration below 15 ppm according to the Risk Assessment Committee (RAC) of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). In view of a harmonized classification, concerns rose on the use of other isothiazolines at low dosages (<15 ppm) that are insufficient in-can preservation. In parallel, the present options for alternative preservatives are limited through the Article 95 List, on which 52 active ingredients are listed and only 15 are compatible with paints and coatings [4]. Therefore, the availability of biocides for in-can preservation is restricted and puts high pressure on industrial applications.

Figure 1.

Isothiazolinones presently used in the industry for in-can preservation of paint: (a) BIT (CAS 2634-33-5), (b) MIT (CAS 2682-20-4), (c) OIT (CAS 26530-20-1), (d) CMIT (CAS 26172-55-4), (e) DCOIT (CAS 64359-81-5).

Present solutions for the short-term are limited, and long-term developments should take into account novel preservation systems, as reviewed in this contribution. This overview focusses on compositional aspects of waterborne paints or latex (e.g., acrylates) and does not detail additional measures that can be taken to enhance paint preservation, such as raw material screening, pasteurization, thermal treatments, plant hygiene and anti-septic packaging. Additionally, alternative systems such as high-pH paints and dispersible powder paints are not further discussed.

2. Current Industrial Trends in the Preservation of Waterborne Paint

2.1. Blending of Biocide Formulations

The limits for reducing concentrations of isothiazolines are set by the inhibitory concentrations of MIT and BIT required in order for them to function as efficient biocides (Table 1) [5]. For most single biocides, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is above the threshold value for selected laboratory strains, whereas even a higher concentration might be necessary in practice to mitigate wild strains [6]. It should be noticed that some biocides have deficiencies or “gaps” in their performance, e.g., the limited anti-fungal properties of BIT and MIT. By using biocide blends, a synergistic biocidal effect was observed with an impressive decrease in minimum inhibitory concentration, below regulatory limits. In parallel, the chances bacteria developing resistance against biocides significantly reduces when they are exposed to blends rather than single active ingredients [7]. Bacteria originating from biofilms are indeed known to have significantly increased tolerance towards common biocides used for in-can preservation, and the minimum inhibitory concentrations are indeed exceeded in paints. The biocide blending also allows one to combine biocides both short-term activity (e.g., O-formals or CMIT) and biocides that provide long-term protection (e.g., BIT). By selecting a combination of active ingredients within an optimum concentration ratio, compatibility can be created regarding properties such as pH and redox potential. The two most promising and versatile platforms for in-can preservation are based on a combination of MIT and BIT in a ratio of 1:1 (for pH ranges between 2 and 11), and a combination of CMIT and MIT in a ratio of 3:1 (for pH ranges below 8) [8]. By utilizing MIT/BIT and CMIT/MIT blends, new generations of in-can biocides were industrially developed that can outperform traditional biocides by a factor of two or more without cautionary labelling related to the European legislation [9]. In such formulations, CMIT and MIT can be used at concentrations below 15 ppm [10]. CMIT has been identified as a skin sensitizer at concentrations above 64 ppm, but that concentration has been avoided.

Table 1.

Biocide activity (MIC values) of isothiazolines and their blends against laboratory-scale organism cultures (data summarized according to [5,6]).

The blending of isothiazolines with 2-bromo-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol (bronopol), in particular, CMIT/MIT, was used to improve the efficiency of MIT at low concentrations. Dosages for those systems can vary with sample preparations, e.g., from 60 ppm bronopol + 10 ppm CMIT/MIT to 200 ppm bronopol + 33 ppm CMIT/MIT, depending on the severity of the contamination and the substrate. A concentration ratio of 6:1 bronopol to CMIT/MIT was recommended [11], and with bronopol, the dosage of CMIT/MIT can be reduced from 20 to 30 ppm to 7.5 to 15 ppm. Bronopol has been utilized to control bacteria that have developed tolerance or resistance against other biocides based on fomaldehyde or isothiazolines. Recently, the interest in bronopol was mainly raised for headspace preservation.

The combinations of BIT with pyrithione (PT) active agents, which are known as traditional fungicides, are finding increased use as co-biocides for in-can preservation of latexes. The pyrithiones interact with the microbial membranes as chelating agents and disrupt essential ion gradients. However, only specific Zn-pyrithiones (ZPT) or Na-pyrithiones (NPT) are applicable, as other cations result in strong coloration. The chelation complexes with Fe2+ or Cu+ ions result in insoluble compounds and blue color for only small concentrations of ions present. The pass levels in antimicrobial testing for sample formulations of 2% BIT + 8% NPT and 2% BIT + 4% NPT were achieved at biocide concentrations of 0.10%. The biocide could be used up to a maximum concentration of 0.25% with an acceptable BIT level [12]. In particular, the BIT/ZPT blend is an efficient biocide against Pseudomonas bacteria that are more resistant against other preservatives (see Table 1).

Other types of biocide are added as co-preservatives to enhance the performance of CMIT/MIT and BIT at low dosages, such as 2,2-dibromo-3-nitrilopropionamide (DBNPA), dichloro-2-n-octyl-4-isothiazoline-3-one (DCOIT), sorbate, sodium benzoate, o-phenylphenol sodium salt and carbamate [13]. However, some of them are problematic due to various reasons related to the specific biocide/fungicide activity, color, hydrolysis, and high concentration requirements. Although covering a broad activity range against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, yeast, fungi and algae, DBNPA is known to have fast but brief activity. New micro-emulsion technologies need to be developed using DCOIT.

2.2. Metal-Based Additives

The antimicrobial properties of metal-oxide nanoparticles have been demonstrated in several fields, such as textiles, packaging, cosmetics and biomedicine. Paint formulators have mainly used silver ions or silver nanoparticles. The silver ions directly interact with the bacterial metabolism, preventing the conversion of nutrients into energy and inhibiting the survival, reproduction and colonization of bacteria. The silver additives can be based on silver phosphate glass active ingredients, and silver ions are effective against a broad spectrum of bacteria. However, in-can preservation with silver ions requires a high ion concentration to be efficient, and in consequence, is expensive, so the industrial application of this technique remains limited. Therefore, it is more attractive in use silver for dry-film protection, which also presents anti-fungal activity when used as additive in waterborne acrylic indoor paints [14].

Other metal oxides, such as ZnO, TiO2, SiO2 and MgO, have additional photocatalytic activity and can release reactive oxygen substances to kill bacteria under UV radiation. In particular, zinc oxide and other zinc complexes have been used as dry-film preservatives in exterior coatings to reduce fungi and algae growth. The addition of ZnO nanoparticles in a waterborne acrylic latex coating provided stable dispersions with enhanced physico-chemical, mechanical and anti-corrosive properties in parallel with antimicrobial resistance at a lower concentration than biocides in commercial paints [15]. Indeed, acrylic paints may benefit from ZnO nanoparticles through antimicrobial properties and low toxicity [16], and the active role of the oxide species may be further enhanced through the combination of ZnO nanoparticles in oxide/amine composites added into the acrylic paint [17]. Alternatively, the interior paints which are water-based acrylate dispersions with MgO nanoparticles provide antimicrobial properties due to the morphology of the nanoparticles (sharp edges) and the formation of reactive oxygen species that induce the peroxidation of lipids in the bacterial cells [18]. Functionalized SiO2 mostly showed an effect against algal growth in dry paints and was also beneficial due to its non-leaching properties [19]. However, the future applications of metal nanoparticles must face toxicity risk assessments.

It may be wise to shift towards naturally-based nanoparticles with demonstrated antibacterial properties in waterborne polyurethane systems, including clay-based minerals. Halloysite nanotubes were formulated with encapsulated carvacrol and allowed sustained release and antibacterial activity over a long period [20].

3. Novel Bio-Based Trends in the Preservation of Waterborne Paint

The need to consider alternative preservation mechanisms instead of traditional isothiazolines is due to:

- (i)

- All types of isothiazolines are inherent skin sensitizers, although at different concentrations. The classification of MIT as a skin sensitizer at a low concentration might set a precedent for other types, such as CMIT, CMIT/MIT and BIT, finally leading to homogenized legislation and reduced usage of all isothiazolines. The eventual scarcity in supply and banning of common isothiazolines threaten the paint industry.

- (ii)

- Micro-organisms are developing increased tolerance against isothiazolines and need exposure to different classes of biocides.

Apart from current industrial approaches, more sustainable innovations for in-can preservation using bio-based compounds are to be expected. The development of novel mechanisms can be inspired through natural antimicrobial systems. Some natural polymeric materials exhibit antimicrobial activity, which can be considered for in-can preservation of paints. The presented solutions, however, are not yet common practice in the paint industry but are promising. Indeed, the development of novel in-can preservation will require appropriate development time and resources. The inspiration for natural preservatives can be found in other domains, such as cosmetics and food preservation, where commonly applied natural preservatives include plant extracts, chitosan or oligosaccharide derivatives, bacteriocins, bioactive peptides and essential oils.

3.1. Acids

Mild bio-based and/or biodegradable organic acids and combinations thereof are applied in cleaning, disinfection, food and personal care products. Their antibacterial mechanisms are based on combinations of effects, such as interacting with the bacterial cell membrane and acting as chelating agents to disrupt the sequestration of nutrients. Acidic conditions disrupt cell regulation at a general level and inhibit the fermentation processes, thereby preventing bacterial growth. The amphiphilic nature of these molecules and their combinations with acids or other surfactants often enable interactions with the cell membrane (lipid bilayer) and enhance cell permeability. Acids for in-can preservation are compatible with the low pHs of paint formulations, and their performances can be further boosted by other paint additives.

Lactic acid is a plant-based active ingredient against Gram-negative bacteria and is compatible with paint formulations that include a cationic surfactant system at have pHs below 4.5 [21]. The preservative effect of lactic acid can be attributed to the production of antimicrobial substances such as hydrogen peroxide and the promotion of an acidic environment. The concentration affinities of lactic acid for fifty strains were demonstrated, showing a clear inhibitory effect at low pHs that was maintained even at a neutral pH [22]. Zinc lactate is a zinc salt derived from lactic acid that also combines antimicrobial properties against bacteria and yeasts [23].

The use of other acids, such as caprylhydroxamic acid, benzoic acid, sorbic acid and their combinations with polyols such as glyverin, propylene glycol, propanediol and hexane diol, rely on the creation of multiple barriers against microbial growth and tunability against a broad spectrum of antimicrobial control [24].

3.2. Antimicrobial Polymers

The cationic polymers bearing positive charges and their assemblies may generally serve as favorable antimicrobial compounds [25]. The presence of quaternary ammonium groups in a polymer structure is a well-known example, as it also occurs in nature. Alternatives include polymer compounds with halogens, phosphor or sulphonates; organometalic polymers; and phenol and benzoic acid [26]. Cationic amines are available as industrial solutions; however, the incorporation of cationic biocides into an acrylic paint formulation is challenging and requires additional chemical modifications, as most water-based paints are anionically stabilized. As such, an antimicrobial waterborne polyurethane paint was developed via transformation into a quaternary ammonium salt emulsion [27]. The modified paint also shows better dispersion stability and small particle sizes, in parallel with hydrophobicity—enhancing the antimicrobial effects—which can be regulated by selection of a chain extender with a long hydrocarbon tail. In particular, the quaternizing of tertiary amines with different alkyl bromides was systematically investigated and indicated higher killing efficiency for bacterial and fungal strains with a longer alkyl chain [28]. The waterborne poly(methacrylate) suspensions were prepared with this type of antimicrobial hyper-branched emulsifier. Other cationic acrylate emulsions with antimicrobial copolymers were synthesized using alternative quaternary ammonium compounds or ammonium chloride derivates [29].

Chitin is a natural biopolymer recovered through extraction from crustaceans, and it has intrinsic antimicrobial properties. Chitosan has reactive amino groups on its pyranose ring and becomes a cationic polymer upon protonation of the amino groups. However, chitosan simply added to waterborne coatings cannot uniformly disperse. Furthermore, when chitosan-acid solution is added to waterborne coatings using acrylic emulsions, precipitates are formed because chitosan is a cationic polymer. Therefore, the incorporation of chitosan in paint formulations has been rarely considered, but one method for preparation of a hybridized chitin-acrylic emulsion was developed through emulsion polymerization and optimization of the pre-emulsification methods. When the products were applied as interior finishing coats, a reduction in formaldehyde content of the paint was observed [30]. The synthesis by emulsion polymerization of an acrylic resin with a quaternary ammonium salt (hybrid chitosan/acrylic resin emulsion) also resulted in better stability and less leaching due to better cross-linking between the acrylic resin particles [31]. Polyurethane paints could also be modified by the addition of chitosan/bentonite nanocomposites to improve antimicrobial properties [32]. As a more advanced approach, emulsion paints were modified through the addition of chitosan-grafted acrylic acid [33]. The chitosan-grafted acrylic acid was then used as an additive in a modified emulsion paint. The produce had higher density, more flexibility, better adhesion to the substrate and shorter drying times. The antimicrobial performance of the wet paint benefits from the presence of chitosan. It depends on the grafting efficiency and concentration of the grafted acrylic acid.

3.3. Bio-Engineered Enzymes and Peptide-Based Polymers

Enzymes that can be used as additives will assist in the inhibition of bacterial growth, e.g., through degradation of the cell wall (lysozymes), interaction with the biofilm or glycocalyx (alginate lyase) or generation of reactive oxygen species (glucose oxidase). Glucose oxidase favors the oxidation of glucose and the release of hydrogen peroxide, which creates damage to the cell wall and causes the destruction of lipids, proteins and sugars. The synergistic effects of bio-based biocides such as glucose oxidase and lysozymes added to traditional paints with MIT biocide were demonstrated [34]. They reduced the necessary concentrations of MIT.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMP) typically have a length of 6 or 7 amino acids and have inherent activity against certain bacteria, fungi and molds, depending on the peptide. Cationic peptides are designed with amino acids that have net positive charges (e.g., arginine, lysine and histidine) and hydrophobic amino acids (e.g., leucine and phenylalanine). The biocidal activity of AMP can be related to the permeation and disruption of the nuclear membrane. Screening of hexapeptides (AMP-6) and heptapeptides (AMP-7) as in-can preservatives for styrene-acrylic latex showed synergistic effects with concentrations of MIT below 15 ppm [35]: AMP-6 showed the best activity against fungi, whereas AMP-7 was satisfactory against both bacteria and fungi. A reduction in cellular metabolism of about 50% was observed when AMP-7 was added at 0.5–0.005 mg/mL. In future, it is believed that the peptide diversity in databases and access to large-scale synthetic production will allow researchers to adapt the antimicrobial activity of AMP for different paint systems.

3.4. Antimicrobial Nanocellulose

The addition of nanocellulose in waterborne coatings has been recently studied. Better service lives of the wood surfaces and higher mechanical resistance were found [36]. As a waterborne agent, it enables the control of paint rheology, in addition to improvements in antifouling and antibacterial properties after surface modification [37]. The antimicrobial properties of nanocellulose against bacteria, fungi and algae can be tuned with functional groups, such as aldehydes; quaternary ammonium; metal oxide nanoparticles; and chitosan [38]. Although mostly suggested for use in antimicrobial paint, nanocellulose is also compatible with waterborne acrylic dispersions, wherein the cellulose nanofibers (CNF) could be homogeneously mixed after facile mixing with small concentrations of aminopropyl-triethoxysilane under ultrasonic treatment and stirring [39]. The cationic or zwitterionic properties of modified nanocellulose after surface modifications with chemical grafting or adsorption of polyelectrolyte layers by electrostatic self-assembly may introduce antimicrobial properties. In contrast, cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) could be used more straightforwardly as a reinforcement filler in waterborne coatings. CNF would provide better mechanical reinforcement and barrier properties with their dense fibrillar network; however, acrylate/CNF dispersions have high viscosity [40]. As such, nanocellulose could serve as a multifunctional bio-based ingredient for waterborne paint formulations.

4. Conclusions

In view of more strict regulations on biocides, the preservation of waterborne paint formulations is a huge challenge for coating and paint industries. Present solutions at the industrial scale focus on decreasing minimum inhibitory concentrations for isothiazolines through blending. Opportunities for disruptive and innovative technologies are offered by bio-inspired materials but will certainly need more development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and P.C.; methodology, P.S.; formal analysis, P.S., J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.; writing—review and editing, P.S., J.B. and P.C.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by VLAIO, grant number HBC.2019.2493.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lorenzen, J.; Poulsen, S. Eco-Friendly Production of Waterborne Paint; The Danish Environmental Protection Agency: Odense, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kharadi, N.; Mistry, R. Economic Impact of Losing Effective In-Can Preservatives; International Association for Soaps, Detergents and Maintenance Products: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.; Silva, C.; Soares, P.; Garrido, E.M.; Borges, F.; Garrido, J. Isothiazolinone biocides: Chemistry, biological and toxicity profiles. Molecules 2020, 5, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, A.; Schmal, V.; Gschrei, S. Survey on Alternatives for In-Can Preservation for Varnishes, Paints and Adhesives; Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, W. Relationship between chemical structure and activity or mode of action of microbiocides. In Directory of Microbiocides for the Protection of Materials; Paulus, W., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gillatt, J.; Julian, K.; Brett, K.; Goldbach, M.; Grohmann, J.; Heer, B.; Nichols, K.; Roden, K.; Rook, T.; Schubert, T.; et al. The microbial resistance of polymer dispersions and the efficacy of polymer dispersion biocides—A statistically validated method. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 104, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, A.D.; Davies, R.H. Co-selection of resistance to antibiotics, biocides and heavy metals, and its relevance to foodborne pathogens. Antibiotics 2015, 4, 567–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.J.; Lim, K.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Kwack, S.J.; Kwon, Y.C.; Kang, J.S.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, B.M. Risk assessment of 5-chloro-2-methylisothiazol-3(2h)-one/2-methylisothiazol-3(2h)-one (cmit/mit) used as a preservative in cosmetics. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 35, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur, J.; Browne, B.A. Innovating in-can preservatives depends on finding and testing the perfect blend. Paint Coat. Ind. 2021, 17, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, R. Guidance on the Use of Globally-Relevant Modern Biocides; Technical Papers; The Pressure Sensitive Tape Council: Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 2013; Volume 38, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- BASF. Industrial Product Preservation; BASF: Ludwigshafen, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.A. Past, present, and future options for preservative in coatings. Coat. World 2017, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak, M.C.; Konst, G.B.; Schwingel, W. Non-traditional use of the biocide DBNPA in coatings manufacture. JCT Coat. Technol. 2005, 2, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bellotti, N.; Romagnoli, R.; Quintero, C.; Dominguez-Wong, C.; Ruiz, F.; Deya, C. Nanoparticles as antifungal additives for indoor water borne paints. Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 86, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankova, M.; Kalendova, A.; Machotova, J. Waterborne coatings based on acrylic latex containing nanostructured ZnO as an active additive. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2020, 17, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, J.J.; Silva, L.L.; Picolli, K.C.; Ternus, R.; Ilha, J.; Decalton, F.; Mello, J.M.M.; Riella, H.G.; Fiori, M.A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles as antimicrobial additive for acrylic paint. Mater. Sci. Forum 2017, 899, 148–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.B.; Antoniuos, M.S.; Mekewi, M.A.; Badawi, A.M.; Gabr, A.M.; El Bagdady, K. Nano ZnO/amine composites antimicrobial additives to acrylic paints. Egypt J. Petrol. 2015, 24, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinerova, D.; Kalendova, A.; Machotova, J.; Pejchalova, M. Environmentally friendly water-based self-crosslinking acrylate dispersion containing magnesium nanoparticles and their films exhibiting antimicrobial properties. Coatings 2020, 10, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dileep, P.; Jacob, S.; Narayanankutty, S.K. Functionalized nanosilica as an antimicrobial additive for waterborne paints. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 142, 105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendessi, S.; Sevinins, E.B.; Unal, S.; Cebeci, F.C.; Menceloglu, Y.Z.; Unal, H. Antibacterial sustained-release coatings from halloysite nanotubes/waterborne polyurethanes. Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 101, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevick-Nikolic, S.; Dimic, G.; Mojovic, L.; Pejin, J.; Djukic-Vukovic, A.; Kocic-Tanackov, S. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid against pathogen and spoilage microorganisms. J. Food Proc. Pres. 2015, 40, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, A.; Bhalla, P.; Sharma, K.B. Evaluation of lactic acid as an antibacterial agent. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 1979, 45, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amrouche, T.; Noll, K.S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chikindas, M.L. Antibacterial activity of subtilosin alone and combined with curcumin, poly-lysine and zinc lactate against listeria monocytogenes strains. Probiotics Antimicrob. Prot. 2010, 2, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, M.; Sol, C.; de Nova, P.J.; Puyalto, M.; Mesas, L.; Puente, H.; Mencía-Ares, Ó.; Miranda, R.; Argüello, H.; Rubio, P.; et al. Antimicrobial activity of a selection of organic acids, their salts and essential oils against swine enteropathogenic bacteria. Porc. Heatlh Manag. 2019, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Carrasco, L.D. Cationic antimicrobial polymers and their assemblies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9905–9946. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaruzzaman, N.F.; Tan, L.P.; Hamdan, R.H.; Choong, S.S.; Woing, W.K.; Gibson, A.J.; Chivu, A.; Pina, M. Antimicrobial polymers: The potential replacement of existing antibiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, T.; Ma, P.; Zhang, H.; Du, M.; Chen, M.; Dong, W. Antimicrobial waterborne polyurethanes based on quaternary ammonium compounds. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Mecozzi, F.; Wessel, S.; Fieten, B.; Driesse, M.; Woudstra, W.; Busscher, H.J.; Mei, H.C.; Loontjens, T.J.A. Preparation and evaluation of antimicrobial hyperbranched emulsifiers for waterborne coatings. Langmuir 2019, 35, 5779–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.; Gan, J.; Yang, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W. Preparation and antibacterial properties of waterborne UV cured coating modified by quaternary ammonium compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, T.; Uragami, T.; Matoba, Y. Chitosan-hybridized acrylic resins prepared in emulsion polymerizations and their application as interior finishing coatings. JCT Res. 2005, 2, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, T.; Yasuda, M.; Yako, H.; Matoba, Y.; Uragami, T. Preparation and characterization of hybrid quaternized chitosan/acrylic resin emulsions and their films. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2007, 292, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihayat, T.; Satriananda, S.; Nurhanifa, R. Influence of coating polyurethane with mixture of bentonite and chitosan nanocomposites. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 2049, 020020. [Google Scholar]

- Abolude, O.I. Modification of Emulsion Paint Using Chitosan-Grafted Acrylic Acid. Master’s Thesis, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, T.W.; Kemp, L.K.; McInnes, B.M.; Wilhelm, K.L.; Hurt, J.D.; McDaniel, S.; Rawlins, J.W. Proteins and Peptides as Replacements for Traditional Organic Preservatives. Coat. Technol. 2018, 15, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, S.; McInnis, B.M.; Hurt, J.D.; Kemp, L.K. Biotechnology meets coatings preservation. Coat. World 2019, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, M.; Veigel, S.; Pinkl, S.; Henniges, U.; Zollfrank, C.; Rössler, A.; Gindl-Altmutter, W. Nanocellulosic fillers for waterborne wood coatings: Reinforcement effect on free-standing coating films. Wood Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguilar-Sanchez, A.; Jalvo, B.; Mautner, A.; Nameer, S.; Pöhler, T.; Tammelin, T.; Mathew, A.J. aterborne nanocellulose coatings for improving the antifouling and antibacterial proper-ties of polyethersulfone membranes. J. Membrane Sci. 2021, 620, 118842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrahim, M.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Jenol, M.A.; Farid, M.A.; Janudin, N.; Ujang, F.A.; Yasim-Anuar, T.A.; Najmuddine, S.U.; Ilyasf, R.A. Emerging development of nanocellulose as an antimicrobial material: An overview. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 3538–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Yu, H. Homogeneous dispersion of cellulose nanofibers in waterborne acrylic coatings with improved properties and unreduced transparency. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3766–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.L.; Fadel, S.M.; Hassan, E.A. Acrylate/nanofibrillated cellulose nanocomposites and their use for paper coating. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, 4963834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).