Women in the Stone Sector: Challenges and Opportunities from an Educational Point of View †

Abstract

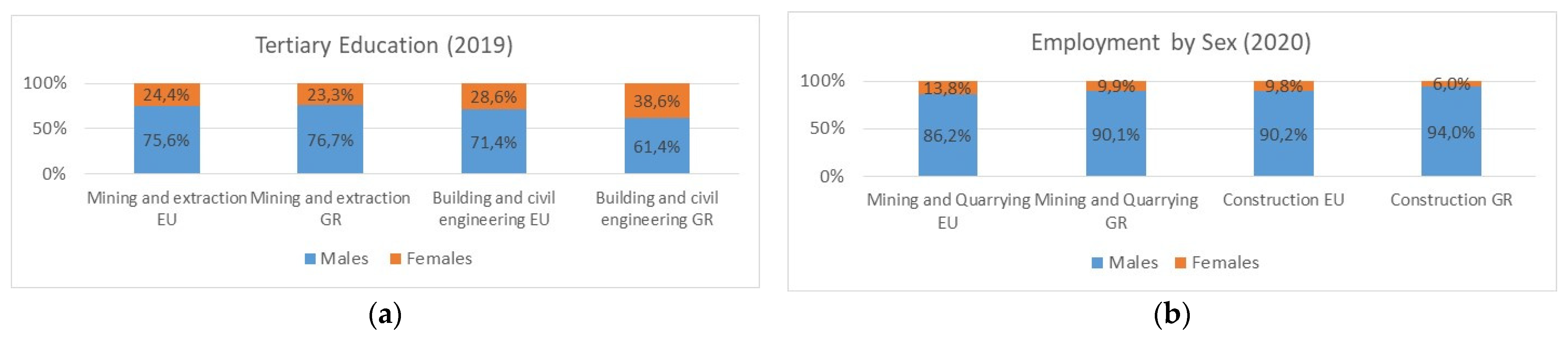

:1. Introduction

2. The Training Needs of Women

- The necessary historical and theoretical background so that the trainees obtain the required knowledge about their professional subject that better be taught in a wider frame than inside the strict lines of the position’s requirements. The industry should be studied as a whole while emphasizing its place during the historical and social evolution. This background could help trainees build their professional profile, be efficient, and be flexible in undertaking work tasks.

- All the skills needed for successful development in their professional field, and to ensure the smooth operation of the business. Nowadays, companies’ operations are becoming more and more digital, which necessitates strong computer skills, software knowledge, and analytical skills [18]. These skills could also enhance communication skills and promote networking, which are also imperative.

- Technical knowledge and skills of all stages of the value chain, from quarry planning production to distribution of final products in the market (value chain). Sales and marketing strategies are an integral part of the value chain of the stone sector.

- The self-improvement and continuous development of employees by cultivating skills such as being a good listener, speaker, and collaborator, having empathy, flexibility in thinking, strategic thinking skills, creativity, and the ability to inspire and persuade.

3. Trainers’ Characteristics

4. Design and Evaluation of the Training Program

4.1. Analysis of the Training Needs

4.2. Design of the Training Program

4.3. Development of the Training Program

4.4. Implementation

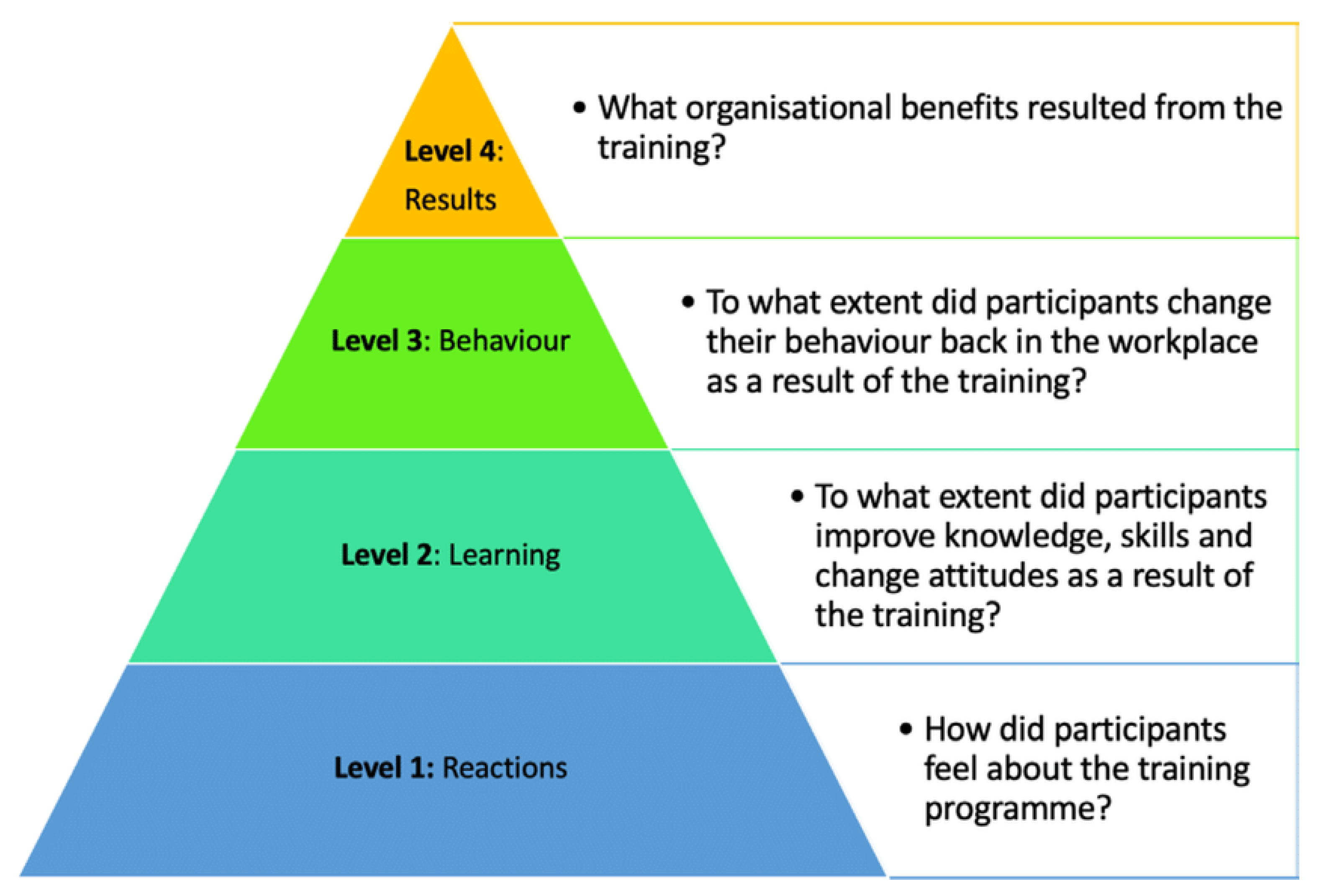

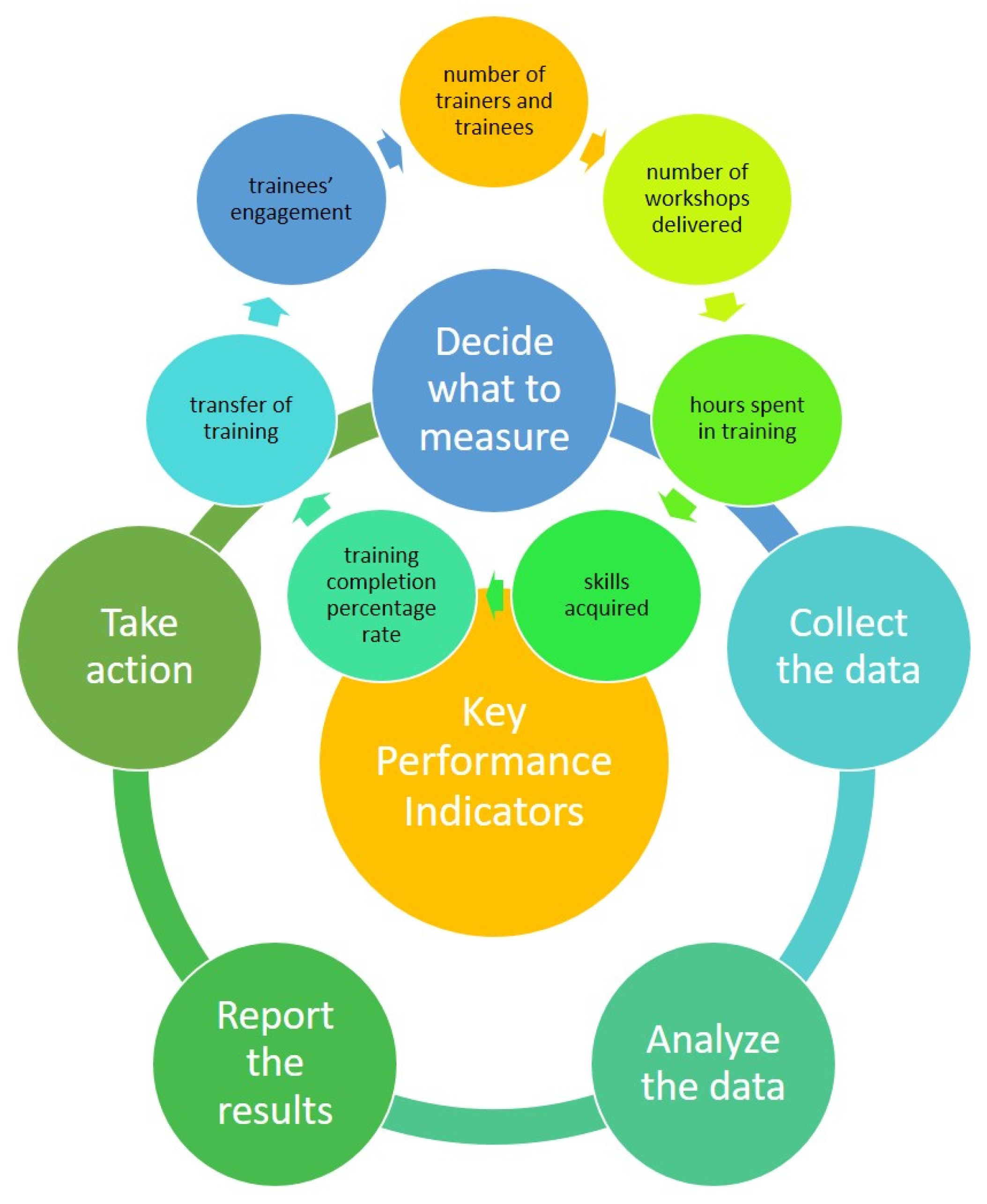

4.5. Evaluation

- Level 1: Evaluate learners’ reactions to training. This is usually measured after training by means of a survey about the overall satisfaction of the participants with the learning experience;

- Level 2: Measure what was learned during training. This is accomplished by utilizing assessments aimed at measuring the degree of change in knowledge and skills after the training program;

- Level 3: Assess whether or not (and how much) behavior has changed as a result of training. Ideally, this is measured by workplace observations and comparing 360° reviews before and after training;

- Level 4: Finally, it is very important to evaluate the impact of participants’ training program on business results. It is common to measure productivity, quality, efficiency, and customer satisfaction.

- Raising awareness about the relevance of gender equality considerations in various policy areas;

- Lowering resistance to mainstreaming gender equality;

- Developing knowledge and skills on how to mainstream gender in day-to-day work;

- Developing competencies on how to use gender equality tools.

- Implementation of new policies, practices, and activities where gender is mainstreamed;

- Consulting with different actors to ensure that different voices are heard in the decision-making process;

- Use of gender-sensitive language and material within the organization;

- Clearly formulated performance indicators that can be used to plan future initiatives.

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat, Statistics for Employment by Sex, Age and Economic Activity (from 2008 Onwards, NACE Rev. 2). Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfsa_egan2&lang=en (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Eurostat, The Life of Women and Men in Europe, A STATISTICAL PORTRAIT. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/womenmen/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Eurostat, Women in Science and Engineering. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20210210-1 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Eurostat, Statistics for Students Enrolled in Tertiary Education by Education Level, Programme Orientation, Sex and Field of Education. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=educ_uoe_enrt03&lang=en (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Knowles, M. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy; The Adult Education Company: New York, NY, USA, 1970; ISBN 0-8428-2213-5. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group Women’s Employment in the Extractive Industry, World Bank Group Energy & Extractives No. 2. Available online: https://olc.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/WB_Nairobi_Notes_2_RD3.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Integrating Gender in Mining Operations. Available online: https://www.commdev.org/downloads/integrating-gender-in-mining-operations (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Women in Mining (UK); Pricewaterhouse Coopers. Mining for Talent A Review of Women on Boards in the Mining Industry 2012–2014; Pricewaterhouse Coopers: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Investing in Women’s Employment: Good for Business, Good for Development; International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- der Lippe, T.V.; Breeschoten, L.V.; Hek, M.V. Organizational Work–Life Policies and the Gender Wage Gap in European Workplaces. Work. Occup. 2019, 46, 111–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyonette, C.; Baldauf, B. Family Friendly Working Policies and Practices: Motivations, Influences and Impacts for Employers; Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick: Warwick, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Unlocking Opportunities For Women And Business, A Toolkit of Actions and Strategies for Oil, Gas, and Mining Companies. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/gender+at+ifc/resources/unlocking-opportunities-for-women-and-business (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Tavris, C. The Mismeasure of Woman. Fem. Psychol. 1993, 3, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaw, J. No Passive Victims, No Separate Spheres: A Feminist Perspective on Technology’s History. In In Context: History and the History of Technology, Essays in Honor of Melvin Kranzeberg; Lehigh University Press: Bethlehem, PA, USA, 1989; pp. 172–191. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, S. Computational Reticence: Why women fear the intimate machine. In Technology and Women’s Voices; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, W. The Power and the Pleasure? A Research Agenda for “Making Gender Stick” to Engineers. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sismondo, S. An Introduction to Science and Technology Studies, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4443-5888-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, D. Technology Is Changing the Way the Mining Industry Works, So What Will the Mining Jobs of the Future Look Like? Available online: https://www.miningpeople.com.au/news/what-skills-and-qualifications-will-your-future-mining-team-need?fbclid=IwAR28fbDqjs4r-vAFr_I5OAx83F2KUSsFm2Woz3oN9ErqrQZayqh6ePZ (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Gender Equality Index. Key Findings for the EU. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2020 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Ostrouch-Kamińska, J.; Vieira, C. Gender Sensitive Adult Education: Critical Perspective. Rev. Port. Pedagog. 2016, 50, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Finnegan, G.; Haspels, N.; Deelen, N.; Seltik, H.; Majurin, E. Gender and Entrepreneurship Together: GET Ahead for Women in Enterprise: Training Package and Resource Kit; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OXFAM. Position Paper on Gender Justice and the Extractive Industries. Available online: https://www.oxfam.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/EI_and_GJ_position_paper_v.15_FINAL_03202017_green_Kenny.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Branson, R.K.; Rayner, G.T.; Cox, J.L.; Furman, J.P.; King, F.J.; Hannum, W.H. Interservice Procedures for Instructional Systems Development: Executive Summary and Model, Vols 1-5; U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command: Ft. Monroe, VA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, W.C. Overview and Evolution of the ADDIE Training System. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2006, 8, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, S. Definitions of the Addie Model. Available online: https://educationaltechnology.net/definitions-addie-model/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Branch, R.M. Instructional Design-The ADDIE Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Gender Equality Training. Gender Mainstreaming Toolkit. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-equality-training-gender-mainstreaming-toolkit (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- International Labor Organization (ILO). Trainers’ Manual: Women Workers’ Rights and Gender Equality: Easy Steps for Workers in Cambodia. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_bk_pb_172_en.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Kirkpatrick, D.L.; Kirkpatrick, J.D. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels, 3rd ed.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, J.W.; Brown, M.E.L.; Duenas, A.; Finn, G.M.; Gibbins, J. How Effective Is Undergraduate Palliative Care Teaching for Medical Students? A Systematic Literature Review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Toolkit for Mainstreaming and Implementing Gender Equality. Implementing the 2015 OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/toolkit-for-mainstreaming-and-implementing-gender-equality.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- International Labor Organization (ILO). A Manual for Gender Audit Facilitators: The ILO Participatory Gender Audit Methodology, 2nd ed.; ILO (International Labor Organization): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---gender/documents/publication/wcms_187411.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- UN Women Training Centre Gender Equality, Capacity Assessment Tool, 2nd ed.; UN Women Training Center: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-63214-064-7. Available online: https://trainingcentre.unwomen.org/RESOURCES_LIBRARY/Resources_Centre/2_Manual_Gender_Equality_Capacity_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Council of Europe. Combating Gender Stereotypes in and through Education, Report of the 2nd Conference of the Council of Europe National Focal Points on Gender Equality; Council of Europe: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Challenges | Workplace Culture | Facts Reinforcing Diversity |

|---|---|---|

| Pervasive stereotypes | Only men can work in risky, dirty, and difficult environments. The stone industry has a masculine identity since it requires physical strength. Thus, it is not a place for women. This outdated stereotype continues to undermine the capabilities of women and deter women from seeking employment in thesector. Women have been traditionally underrepresented in fields such as engineering and geology, meaning that there has been a smaller pool of women with the technical skills to work in the wider area of the mining sector [6]. | In the era of industry 4.0, the ongoing automation of traditional manufacturing and industrial practices and the use of smart technology, restricting physical effort, could serve as a positive catalyst for women’s engagement in the stone sector. Moreover, evidence has shown that when companies recognize the opportunity of a more diverse workforce and supply chain, they can increase productivity, reduce costs, and strengthen social license to operate [7]. |

| Low rate of women in leadership roles | The mining sector represents some of the lowest rates of women in leadership, at only 7.9 percent of women on the board of directors in the top 500 mining companies globally [8]. | The experience has shown that including women in managerial positions has a positive impact on social development, workplace culture, and productivity. For this reason, many multinational mining companies are setting targets to increase women in managerial and executive roles [6]. |

| Limited flexibility for family | The extractive industries do not often promote a family-friendly workplace. This barrier tends to be more widely felt by women with increased family responsibilities. Due to the male-dominated culture of the sector and the often-remote locations, demanding absence from home and long shifts, women with families often cannot negotiate employment opportunities in the extractive industry [6]. | Research has shown that increasing family-friendly policies, such as childcare, parental leave, and health policies can be cost-effective interventions [9]. The implementation of a number of work–life policies can lead to greater gender equality [10], creating opportunities for women’s career development and reduced gender pay gaps [10]. Managers can be confident that work–life programs are likely to translate into increased employee productivity, and the costs associated with work–life programs should be covered by such increased productivity [11]. |

| Increased discrimination and harassment | Women report higher rates of discrimination and harassment in the extractive industries than their male counterparts, including verbal, physical, and/or sexual harassment, ranging from intimidation to sexual violence against female employees [6]. | Dealing with this issue is complex in every working environment. However, the awareness of the need to incorporate harassment and gender-based violence policies and training as a prerequisite to creating supportive working environments [12], as well as the provision of leadership opportunities for women, would pave the way to address these risks. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maniou, M.; Perraki, M.; Mavrikos, A.; Menegaki, M. Women in the Stone Sector: Challenges and Opportunities from an Educational Point of View. Mater. Proc. 2021, 5, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2021005079

Maniou M, Perraki M, Mavrikos A, Menegaki M. Women in the Stone Sector: Challenges and Opportunities from an Educational Point of View. Materials Proceedings. 2021; 5(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2021005079

Chicago/Turabian StyleManiou, Magdalini, Maria Perraki, Athanassios Mavrikos, and Maria Menegaki. 2021. "Women in the Stone Sector: Challenges and Opportunities from an Educational Point of View" Materials Proceedings 5, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2021005079

APA StyleManiou, M., Perraki, M., Mavrikos, A., & Menegaki, M. (2021). Women in the Stone Sector: Challenges and Opportunities from an Educational Point of View. Materials Proceedings, 5(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2021005079