Evaluation Index for Healing Gardens in Computer-Aided Design †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Therapy and Healing

2.2. Horticultural Therapy

2.3. Landscape Therapy

2.4. Healing Garden Benefits

2.5. Healing Garden Design Principles

3. Materials and Methods

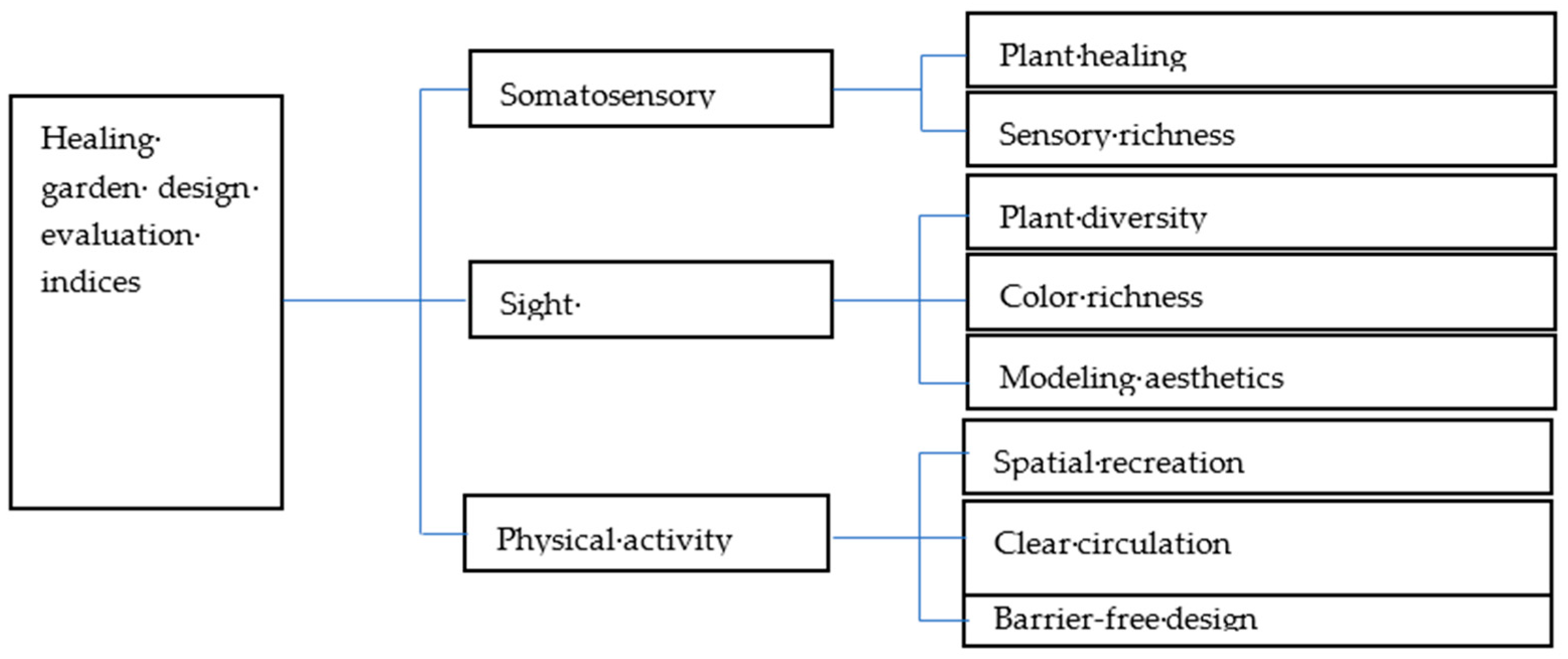

3.1. Healing Landscape Design Indices

3.2. Identified Indices

3.3. Weights of Design Factors

3.4. Healing Garden Design Factors

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Health Organic Garden of Changhua Christian Hospital

4.2. Planning and Design

4.3. Evaluation of Healing Garden Design

- 1.

- Plant healingFour aromatic plants were planted: jasmine, sandalwood, Osmanthus, and mock orange. Plants were rated grade 5 and scored 10 for calming emotions.

- 2.

- Sensory richnessThe design creates a landform for drainage and lawn space, diverse plants, and an ecological pool. Flat, clear pavement circulations and seasonal plant variation were rated grade 5 and scored 10 for the five landscape elements.

- 3.

- Plant diversitySpecies diversity (SDIt) was used for empirical tests, and the result was SDIt = 0.9. Plant diversity was rated grade 5 with SDIt ≥ 0.7, scoring 10.

- 4.

- Color richnessA total of 8401 plants were implemented in the healing garden, with 4464 color changes and a color richness value of 0.53. This earned a grade of 3 and 5 points, as the proportion exceeded 0.5.

- 5.

- Modeling aestheticsThe aesthetic pavilion was added and simply and geometrically ordered in the garden. For durability, artificial materials were used. The modeling aesthetics was rated grade 3 and scored 5.

- 6.

- Spatial recreationThe availability of shaded, sheltered, and secluded resting spaces in the garden was assessed. The daze pavilion provided shade, while the flower stand offered semi-shading. However, the recreational facilities lacked adequate shelter and privacy. As a result, spatial recreation was rated 3, scoring 5 for the shaded resting area.

- 7.

- Clear circulationThe garden featured connected, directional, and clearly defined circulations with single entrances, exits, and safe paths to prevent getting lost. This circulation was rated with a grade, with a score of 10.

- 8.

- Barrier-free designPavements were minimized, with main footpaths roughened with cement to meet barrier-free requirements. However, the gravel paths were not user-friendly. The barrier-free design received a grade of 3 and 5 points.

4.4. Evaluation Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuo, Y.J. Horticulture Therapy & Healing Landscape—Theory & Practical Handbook; Chinese Culture University: Taipei, Taiwan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic landscape. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- AHTA. American Horticultural Therapy Association Definitions and Positions. Available online: https://sites.temple.edu/vrasp/files/2016/12/Horticultural-Therapy-.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2020).

- Huang, S.L. Enter the World of Horticultural Therapy; PsyGarden Publishing Company: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y.R. Meet Horticultural Therapy in Full Bloom; Yang Pei Culture: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Relf, P.D. The therapeutic values of plants. Pediatr. Rehabil. 2005, 8, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.S.; Yang, F. Introducing healing gardens into a compact university campus: Design natural space to create healthy and sustainable campuses. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C. Healing gardens in hospitals. Des. Health 2007, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, T.Y.; Wu, C.C.; Lin, F.L.; Chiu, Y.T.; Yin, Y.S.; Liu, T.C.; Lo, Y.W., Translators; Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations; Marcus, C.C., Barnes, M., Eds.; Wu Nan Books: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins, M.P. Design for Dementia: Planning Environments for the Elderly and the Confused; National Health Publishing Press: Owings Mills, MD, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, C.F.; Clark-McDowell, T. The Sanctuary Garden: Creating a Place of Refuge in Your Yard or Garden; Simon & Schuster Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, D.Y. Outdoor Spaces in Housing for the Elderly. In People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space; Marcus, C.C., Francis, C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 209–257. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel, J.; Tyson, M.M. Alzheimer’s treatment gardens. In Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations; Marcus, C.C., Barnes, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 437–504. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C.; Barnes, M. Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations; John Wiley & Sons Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson, R.A. Healing the Mind, Body, and Soul: A Therapeutic Landscape Design for Crest-Mark of Roselawn. Ph.D. Thesis, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Furgeson, M. Healing Gardens. Available online: http://www.sustland.umn.edu/design/healinggardens.html (accessed on 12 August 2006).

- Noell-Waggoner, E. A Community’s Gift to Those Living with Alzheimer’s Disease and Their Care-Givers. Available online: http://www.centerofdesign.org/pages/memorygarden.html (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Tseng, T.H.; Chang, C.Y.; Hsieh, C.Y. Differences in Hospital Landscape Environments on the Psychological Response of Patients. In Proceedings of the 10th Architectural Research Achievement Conference, Taipei City, Taiwan, 23 November 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.A.; Grahn, P. What makes a garden a healing garden. J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.Y. Design the garden for dementias. J. Sci. Agric. 2001, 49, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.C. The Wellness Design Concept for a Healing Environment. In Proceedings of the 2011 Global and Welfare Forum in Taiwan, Taipei City, Taiwan, 31 October–1 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Year) | Discourse |

|---|---|

| Calkins (1988) [10] | A healing garden should have an environment that provides safety, protection, and diverse social opportunities. |

| McDowell & Clark-McDowell (1998) [11] | The key is not only plants but also the connection between humans and the natural environment. |

| Carstens (1998) [12] | Attention should be paid to constructing directive elements so that users are not at risk of being lost. |

| Zeisel & Tyson (1999) [13] | Visual elements are used to guide users, providing a safe environment. |

| Marcus & Barnes (1999) [14] | In addition to patients, medical workers are also considered users of gardens. |

| Christenson (2006) [15] | Barrier-free planting platforms and cages for birds to perch on should be provided for people to enjoy and stimulate their senses. |

| Furgeson (2006) [16] | A functional, easily maintained, safe, and barrier-free garden environment should be provided to reduce stress and provide comfort and beauty. |

| Noell-Waggoner (2011) [17] | Visual perception supports the function of other sensory organs, making the body strong, balanced, and coordinated. |

| Author (Year) | Design Principles |

|---|---|

| McDowell & Clark-McDowell (1998) [11] | 1. Special entrance and exit; 2. water elements; 3. light source and color; 4. creating an environment according to the characteristics of nature; 5. integrating art into the garden; 6. creating a rich ecological environment |

| Carstens (1998) [12] | 1. Conspicuous single entrance and exit; 2. individuals can enter or exit the garden at any time; 3. a simple and functional design; 4. a facility display area that can bring back memories; 5. avoiding poisonous plants |

| Zeisel & Tyson (1999) [13] | 1. Installing fences or door locks; 2. hints as to the locations of landmarks; 3. arranging areas for activities; 4. planning according to directional circulation; 5. having a nostalgic design; 6. connecting indoor and outdoor spaces |

| Marcus & Barnes (1999) [14] | 1. Spatial diversity; 2. extensive greening and beautification; 3. encouraging individuals to participate in sports; 4. providing positive recreation; 5. decreasing interference; 6. reducing complexity |

| Chang (2001) [20] | 1. Easy access to the garden; 2. clear directions in the garden; 3. high visual penetration; 4. social activities are allowed; 5. spaces where people can engage in exercise; 6. available spaces; 7. things in the garden that can bring back memories; 8. good location relationship; 9. microclimates are considered; 10. several rest areas; 11. spaces fitting for patients’ sizes; 12. familiar with the environment as if living at home; 13. providing personal space; 14. flexible use of space; 15. a barrier-free space; 16. artificial lighting; 17. low maintenance |

| Christenson (2006) [15] | 1. Having sheltered terraces; 2. water elements; 3. flowerbeds at wheelchair level that are suitable for operation; 4. spaces for quiet conversation; 5. circular paths; 6. shaded activity spaces; 7. raised lawns; 8. wildflower gardens; 9. arranging bird cages and feeding areas |

| Furgeson (2006) [16] | 1. Space design that is easy to identify; 2. various materials to promote sensory stimulation; 3. wheelchairs and crutches that touch the ground should be specially selected; 4. provision of landmarks as hints; 5. non-toxic plants; 6. path width suitable for a wheelchair to move in two directions and rotate; 7. proper slopes; 8. arranging water spaces; 9. arranging seats where people can sit for long periods; 10. flowerbeds at a height suitable for operation |

| Noell-Waggoner (2011) [17] | 1. A preview area at the entrance; 2. no dead angles in the path cycle; 3. landmark hints; 4. arranging rings on main paths and benches on the periphery; 5. growing plants common throughout the four seasons in the garden; 6. determining the flowerbed height by considering wheelchair height |

| Wu (2011) [21] | 1. Spaces for interpersonal interaction; 2. providing feelings of five senses; 3. producing environmental identity; 4. integrating culture and linking to nature; 5. eco-resilient choices; and 6. improving a healthy and caring environment |

| Index | Design Factor | Description of Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Touch | 1. Fun of plants 2. Facility variability 3. Landscape richness | 1. Plants have branches and leaves with a textural quality or have fruits. 2. The tactility of facilities is variable. 3. There are landscape elements, including water, stone, and sunlight. |

| Taste | 1. Fun of plants 2. Plant edibility | 1. Bitter tastes might make people feel depressed and sad in the space. 2. Sweet tastes might makes people feel pleasant and relaxed in the environment. |

| Eyesight | 1. Seasonal variability 2. Plant diversity 3. Color richness 4. Modeling aesthetics | 1. Plants vary from season to season. 2. Plants are diverse. 3. Colors are rich. 4. The modeling design is aesthetically pleasing. |

| Smell | 1. Plant healing 2. Fun of plants | 1. Plants emit fragrances that can calm people’s emotions. 2. Plants emit fragrances that can boost people’s moods. |

| Hearing | 1. Bird attraction of plants 2. Fun of plants 3. Landscape richness | 1. Plants that can attract birds. 2. Plants with large leaves or many leaves. 3. There are landscape elements, including wind, water, and birdsong. |

| Physical activity | 1. Spatial recreation 2. Horticultural operation 3. Clear circulation 4. Barrier-free design | 1. There is a shaded, sheltered, and secluded rest space. 2. Space is available for gardening and this is accessible. 3. Circulations are connected, directional, and clearly defined. 4. It is necessary to reduce hard pavements in large areas and the space should be barrier-free. |

| Index Dimension | Index Item | ZI | GI | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healing landscape | Touch | 2.74 | 6.74 | |

| Taste | −1.59 | 4.41 | Removed | |

| Hearing | 2.38 | 6.38 | Removed | |

| Eyesight | 5.24 | 8.24 | ||

| Smell | 1.66 | 6.66 | Removed | |

| Physical activity | 4.95 | 7.95 | ||

| Touch | Fun of plants | 4.79 | 6.79 | |

| Facility variability | 2.30 | 6.30 | Removed | |

| Landscape richness | 2.41 | 7.41 | ||

| Taste | Fun of plants | −0.47 | 4.53 | Removed |

| Plant edibility | −2.12 | 5.88 | Removed | |

| Hearing | Bird attraction of plants | 3.89 | 6.89 | |

| Fun of plants | 2.56 | 5.56 | Removed | |

| Landscape richness | 2.41 | 7.41 | ||

| Eyesight | Seasonal variability | 2.01 | 7.01 | |

| Plant diversity | 3.59 | 7.59 | ||

| Color richness | 5.68 | 7.68 | ||

| Modeling aesthetics | 4.66 | 7.66 | ||

| Smell | Plant healing | 2.52 | 7.52 | |

| Fun of plants | 1.62 | 6.62 | Removed | |

| Physical activity | Spatial recreation | 1.04 | 7.04 | |

| Horticultural operation | 1.72 | 6.72 | Removed | |

| Clear circulation | 2.07 | 7.07 | ||

| Barrier-free design | 2.84 | 7.84 |

| Index Dimension | Design Factors | ZI | GI | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatosensory | Fun of plants | 2.55 | 6.55 | Removed |

| Plant healing | 4.56 | 7.56 | ||

| Sensory richness | 5.68 | 7.68 | ||

| Bird attraction of plants | 2.53 | 6.53 | Removed | |

| Eyesight | Seasonal variability | 0.28 | 6.28 | Removed |

| Plant diversity | 0.90 | 6.90 | ||

| Color richness | 3.46 | 7.46 | ||

| Modeling aesthetics | 5.98 | 7.98 | ||

| Physical activity | Spatial recreation | 2.18 | 7.18 | |

| Horticultural operation | 2.55 | 6.55 | Removed | |

| Clear circulation | 3.45 | 7.45 | ||

| Barrier-free design | 3.81 | 7.81 |

| Index | Factor | Weight | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatosensory | Plant healing | 0.119 | 4 |

| Sensory richness | 0.072 | 6 | |

| Eyesight | Plant diversity | 0.230 | 1 |

| Color richness | 0.207 | 3 | |

| Modeling aesthetics | 0.216 | 2 | |

| Physical activity | Spatial recreation | 0.089 | 5 |

| Clear circulation | 0.039 | 7 | |

| Barrier-free design | 0.028 | 8 |

| Index | Factor | Weights | Score | Weighted Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatosensory | Plant healing | 0.119 | 10 | 1.19 |

| Sensory richness | 0.072 | 10 | 0.72 | |

| Eyesight | Plant diversity | 0.230 | 10 | 2.30 |

| Color richness | 0.207 | 5 | 1.04 | |

| Modeling aesthetics | 0.216 | 5 | 1.08 | |

| Physical activity | Spatial recreation | 0.089 | 5 | 0.45 |

| Clear circulation | 0.039 | 10 | 0.39 | |

| Barrier-free design | 0.028 | 5 | 0.14 | |

| Weighted Total Score | 7.3 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weng, C.-K.; Lai, C.-F.; Yeh, W.-C. Evaluation Index for Healing Gardens in Computer-Aided Design. Eng. Proc. 2025, 98, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025098017

Weng C-K, Lai C-F, Yeh W-C. Evaluation Index for Healing Gardens in Computer-Aided Design. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 98(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025098017

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeng, Cheng-Kai, Chao-Feng Lai, and Wei-Chieh Yeh. 2025. "Evaluation Index for Healing Gardens in Computer-Aided Design" Engineering Proceedings 98, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025098017

APA StyleWeng, C.-K., Lai, C.-F., & Yeh, W.-C. (2025). Evaluation Index for Healing Gardens in Computer-Aided Design. Engineering Proceedings, 98(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025098017