1. Introduction

The Costs of Sprawl, a study by Real Estate Research Corporation (RERC), explored the saturation of urban centers, which hinders and changes the development to the peri-urban or urban fringes, increasing transportation demand [

1]. To ensure speed and convenience, elevated roadway systems have been developed [

2]. Compared with undergrounding, elevated roads are cheaper, faster to build, and more convenient to maintain. Nowadays, the form of urban road structures is more towards three-dimensional development [

3]. The construction of elevated roads in urban areas shortens the distance between destinations and reduces the traffic volume during peak hours in urban areas. However, the impact on the surrounding area in terms of noise, light, air pollution, and the cityscape of the city is huge in the developing city. Noise, light, and air pollution in the surrounding area and the impact on the cityscape after the completion of the project causes various problems [

4]. In Taiwan, the land area is small and densely populated, and the land price in the city is high. The design and use of elevated roads are determined for the convenience of the space on the elevated roads, but the linear space created under the elevated roads is seldom utilized [

2]. The space under bridges has limited sunlight and views and is separated by traffic, which greatly reduces usability, generating unused space under the bridge [

5].

Coleman used the terms “dead space” and “disturbed space” to describe abandoned wasteland or uninhabited building space that is overgrown by no one and left unused [

6]. Liao defined unused space as (1) space with historical and cultural significance that is abandoned and not used, (2) space that is closely related to the residents or industrial culture, (3) space that is not functional at present but can be used more actively, and (4) space that has physical buildings or structures [

7]. Tseng defined unused spaces as buildings whose original spatial functions do not meet the demands of current use, and therefore are rarely or no longer in use. Usually, these spaces have a special atmosphere of history and aesthetics, which trigger people’s imagination and recognition and have been appropriately transformed to provide new functions in line with the trend of the times [

8]. Wei believed that unused space has the following three conditions: (1) the original function has disappeared and the property is unused; (2) it must be a structurally safe building; and (3) it can improve the overall interests of the surrounding area after reuse [

9]. In the past, unused space may have been be an abandoned factory, a historic house, or a section of an old trade route; in the present, it may be an abandoned school or a section of space under a bridge.

There are many unoccupied spaces, and the cultural memories they carry are sometimes important. To define unoccupied space (vacant or unoccupied space), unoccupied space refers to the space that has been legally designated as a monument, recorded as a historic building, undesignated as a historical building, or designated as a historic building according to Article 2 of the “2001 Trial Implementation of Unused space Reuse” from the Council for Cultural Affairs of the Executive Yuan. Unused space is defined as buildings or spaces that are legally designated as monuments, registered as historical buildings, or undesignated as old unused buildings or spaces that are structurally safe and still have the potential to be reutilized to promote arts and culture in Article 2 of the “2001 Trial Implementation Guidelines for the Reuse of Unused space” by the Council for Cultural Affairs, Taiwan. This shows that the government has regarded unused space as a regeneration space for the promotion of cultural and creative industries. Therefore, in urban development, unused space is not abandoned space but the municipal government must make an urban development plan for unused space caused by uneven urban development [

10].

The city’s public places are becoming gradually occupied by forests of concrete, public space is becoming less available, and the land is overused. As people’s quality of life is improving, the need for more public space is increased. Therefore, the values of the unused space under bridges are recognized in alleviating the pressure of traffic, supplementing the city’s public service facilities, supplementing the city’s municipal facilities, and reshaping the cityscape [

2]. Previous studies on the space under bridges are based on spatial theories such as the design of the green corridor for the New Life Viaduct in Taipei City [

11] and the Taichung District Taichung 74th Expressway [

12]. More attention has been paid to architectural and spatial aspects with less focus on spatial attributes under the bridges. Spatial attributes are important in spatial planning, and the importance of urban green corridors from the aspects of spatial attributes has been ignored [

13,

14]. The use of space under bridges enables the safety of space users, traffic, and bridge girders, which necessitates a study on the attribute classification of the space and reasonable planning of the space usage under the bridge to ensure the safety and the comfort of the users.

The term “reuse” refers to the evolution of the concept of preservation of historical buildings. Common reuse of spaces involves renovation, rehabilitation, remodeling, recycling, retrofitting, environmental remodeling, extended use, regeneration, rebirth, and adaptive reuse. The term “reuse” also describes the process of the preservation of the environment, extended use, rebirth, and adaptive reuse among which adaptive reuse best expresses the concept of a new use for old buildings [

15]. The reuse of unused space is related to cultural creation, and the development of culture leads to the change in the basic structure, the effective use of cultural resources, and the combination of spatial development systems to improve the autonomy of local cultural development as an important part of the local economy [

16]. The reuse of unused space enriches, converts, or creates new functions and cultural connotations by reshaping the life, functions, and indiscriminate use of the unused space. With financial expenditures and the needs of the community, a new culture in the community can be created from the reuse of the space [

17].

The reuse of unused land, public buildings, or public construction requires systematic modification of the elements and urban planning. The activity, imagery presentation, and cultural communication in the unused spaces are related to the lives of residents. However, the attributes and values of the unused space under bridges have not been explored extensively. Therefore, we examined the core values of unused spaces under bridges in Taichung, Taiwan. The results provide a reference for the development of the unused by understanding the nature and connotation of the attributes in using unused space under the bridge.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Unused Space

Unused space refers to underutilized or completely unused land or buildings in urban or suburban areas due to industrial changes, population reduction, and insufficient policy planning [

18]. Unused spaces are prone to environmental degradation and increased crime rates [

19]. With proper planning and reuse, unused spaces can be transformed into community resources, cultural and creative spaces, or ecological reserves [

20]. The reuse of unused space in Taiwan has different styles according to changing needs. Taiwanese recent history is categorized into three periods as follows in terms of land use [

21].

During Japanese colonization (1895–1945) and Taiwan’s restoration (1945–present), most unused space generated was institutional land left by government agencies during the Japan-ruling period. Since the original buildings had practical values, only the internal organization changed, so the unused period was short and named the “life extension period”. The way to reuse the space in this period was to convert the space of the old buildings for the Nationalist Government. For example, the Japanese North Military Police in Taipei City, built in 1907, was converted into the Criminal Division of the Police Department after the restoration and became the Taipei City Police Department Zhongzheng Second Branch in 1954. The Taipei Broadcasting Bureau was constructed in 1930 and was taken over by the Central Broadcasting Bureau of the Kuomintang as the Taiwan Broadcasting Administration after the restoration; the Taipei Radio Broadcasting Bureau was renamed the Taiwan Radio Broadcasting Administration. There are many other buildings such as railroad stations that were handed over to the Nationalist government, continuing its vitality of the development of railroad space.

- 2.

Functional transformation period

This period was the period for the development of Taiwan’s agriculture and industry from the 1960s to the 1980s. With the impact of the economic growth, the reuse of space was different to the first period. A large number of urban and rural immigrants led to the stagnation or transformation of the rural space. A large number of factories moved to the rural area due to the development of agriculture, allowing the countryside to commit to manufacturing. At the same time, an accelerated turnover of urban space was observed, which reshaped urban planning. Due to the slow urban planning policy, this period was extended, leaving rural space unused instead of actively using urban space. However, starting in the 1980s, science and technology parks and high-tech industries began to be established, which relocated or caused old industrial buildings to be abandoned. Low-rise buildings were converted into taller buildings or transformed into community parking lots. This reflected a strong economy and vitality that created the miracle of the Taiwanese economy but on the other hand, this led to the stagnant development of their limited hinterland. Abandoned warehouses of railroads, tobacco factories, and distilleries became unused without functional replacement.

- 3.

Spatial construction period

After the mid-1980s, the reuse of unused space was intensified due to global warming and localization and the incentive of the Cultural Affairs Council’s subsidies for general community building. Unlike the long period of indifference to cultural affairs, the government’s assistance allowed the arts and cultural industries to flourish in the reused space. With such artists, the unused space was filled with unlimited creativity and imagination. Even though artists turned unused spaces into art villages, the process was delayed for a long time due to land ownership issues. The proliferation of art villages demonstrated the art development in Taiwan. With the development of Taiwan’s art in globalization, the Huashan Cultural and Artistic Special Zone was established at the former Taipei Distillery, and the Railway Warehouse No. 20 in Taichung, respectively. This surfaced concerns about the illusion of art development with the dissipation of the boom of the art villages insufficient funding and support, and decreased public participation.

2.2. Importance of Public Space

Public space plays a key role in modern urban environments, affecting the functional operation of the city, the quality of life, social interaction, and the mental health of the residents. Public space, including squares, parks, streets, and pedestrian areas, is freely accessed and used by all people [

2]. These spaces often carry social, cultural, economic, and financial functions. The values of public space in terms of social functions is particularly important. Putnam pointed out that public space facilitates interpersonal interactions and enhances social capital and community cohesion in his book “Bowling Alone” [

22]. These spaces provide a place for residents to interact spontaneously, enabling people of different ages, occupations, and cultural backgrounds to interact and build a sense of trust. For example, gatherings and activities in corner parks or squares allow neighborhood residents to get to know each other and form stronger social bonds. Projects such as the Superkilen in Copenhagen created multicultural spaces for integration and allowed different communities to strengthen their sense of belonging to the community through joint activities. Public space is an important carrier of history and cultural memory. Harvey suggested that urban public space carries rich cultural symbols and identities in “The Condition of Postmodernity”. Plazas, monuments, parks, and other spaces are the landmarks of the city and preserve the history of a particular society and era [

23]. For example, the Place de la Concorde in Paris, France, is the place of witness to major historical events and symbolizes freedom, revolution, and social progress. Lefebvre proposed a “spatial production theory”, which suggests that public space is an important place for social interaction and cultural symbolism [

18]. Public space provides a means of emotional relief and stress release. Carr et al. pointed out that green spaces and leisure spaces can fulfill people’s need for rest and improve their emotional and psychological states. The pace of modern urban life is fast, and people need an environment to relax and express their emotions when they feel under pressure [

13]. The Yoyogi Park in Tokyo, Japan, provides the green design and openness of the space for city dwellers with opportunities to be closer to nature, proving the importance of green spaces in reducing anxiety and promoting mental health.

“Public space is the soul of a city, and its existence determines whether a city is livable or not” [

24]. This quote emphasizes the importance of public space to urban development. Modern cities face challenges such as increased population density and compressed living space, and public space has become an important solution to alleviate these pressures by facilitating social interaction, carrying cultural memories, and enhancing mental health. However, the rapid development of cities has led to competition for land resources [

20], and public space has been gradually reduced. Therefore, it is important to plan and transform those unused spaces into good public spaces, which is the most important issue that the government has presently.

Therefore, we explored the spatial attributes under the bridge and future public space planning strategy from the perspective of stakeholders to understand the user’s preference for spatial attributes and propose corresponding programs for the planning and the design to present regional characteristics to satisfy the needs of users.

2.3. Space Under Bridge

With the increasing number of viaducts in cities, the corner spaces between roads and bridges increase, forming a special type of urban space. These spaces are usually located on both sides of railroads, highways, or bridges. Due to the influence of vehicular traffic and the restriction of the surrounding objective environmental factors, these spaces are often isolated and closed by urban arterial roads, lacking effective management and utilization. This makes unused spaces significantly less utilized. Their environmental conditions are relatively poor and have become one of the typical urban passive spaces under the “car-oriented” transportation development mode [

5].

The space under a bridge refers to “the space on the ground under the elevated roadway or bridge approach”. Due to the influence of traffic, sunlight, and surrounding environmental factors, the use of space under bridges must be planned in combination with safety conditions, functional needs, and environmental conditions [

25]. The Multi-Objective Use Methods for Public Facility Sites of the Ministry of the Interior’s Urban Plan proposed eighteen possible uses for elevated roadway underpasses, as follows [

26]:

1. Parks

2. Parking lots, electric motorcycle charging stations and battery exchange stations

3. Car washes

4. Warehouses

5. Shopping centers

6. Fire Brigade

7. Gas stations

8. Police stations

9. Assembly halls and public activity centers

10. Pumping stations | 11. Natural gas pressure regulators and blocking facilities

12. Bus stop facilities and marshaling stations

13. Other necessary governmental authorities

14. Electricity distribution premises, transformer substations, and their necessary electrical and mechanical facilities

15. Telecommunication equipment rooms

16. Resource recycle bins

17. Water, reclaimed water and sewerage system related facilities

18. Recreationals facilities |

Such facilities must not obstruct traffic and shall be equipped with perfect ventilation, fire fighting, landscape, sanitary, and safety facilities, among which the use of recreational and sports facilities must be in the same category as parkland; a natural gas pressurization station must be indoors or underground. Shopping malls must accommodate daily necessity retail stores, general retail stores (excluding automobile repair), daily service shops (excluding laundry and dyeing), and offices. The lower floors can be used for the following purposes. The use of the lower floor as a resource recycling station or natural gas pressurization station must be properly planned and managed following the laws and regulations on environmental protection and fire prevention, and the consent of the road administration of the building must be obtained.

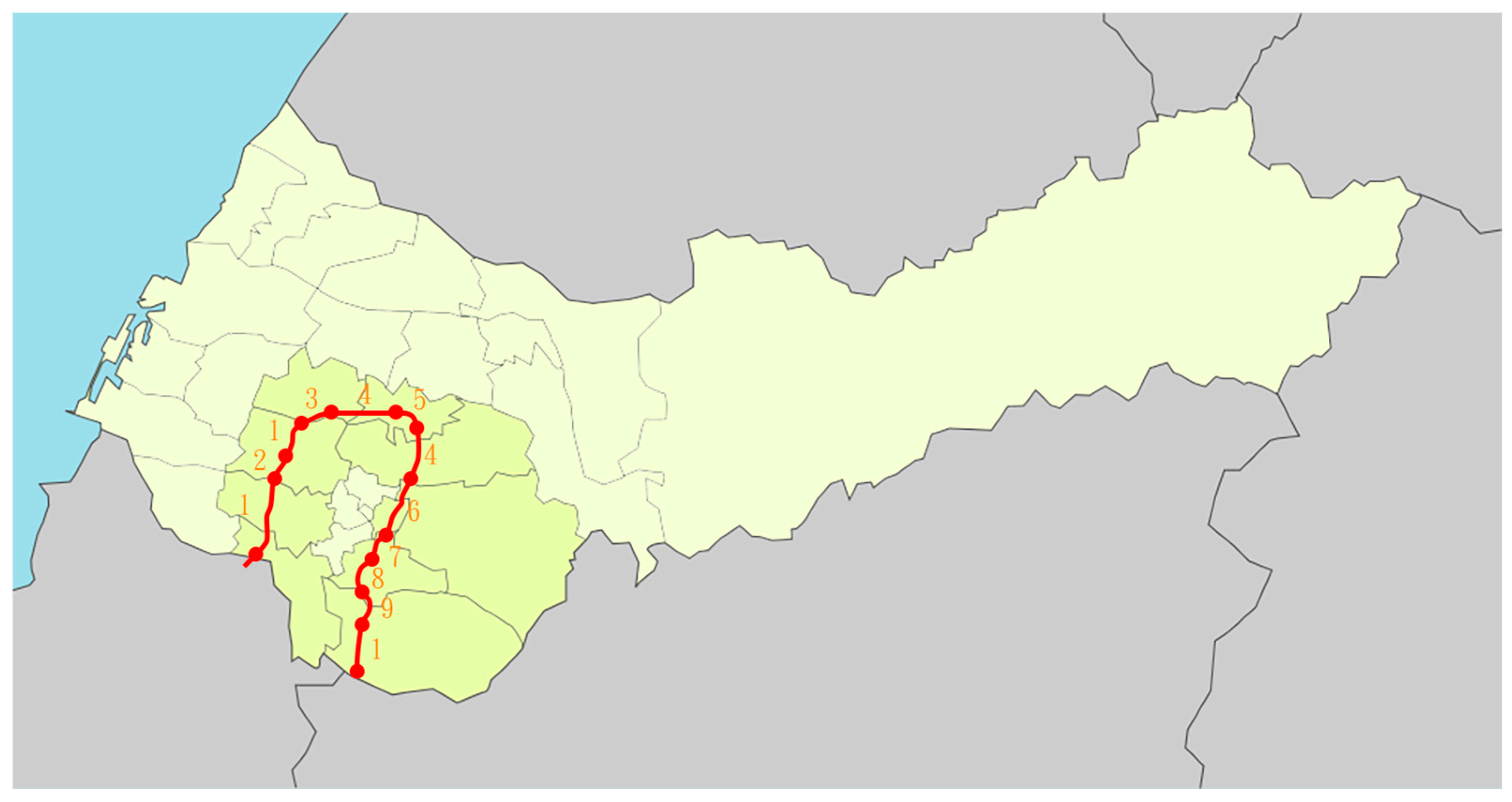

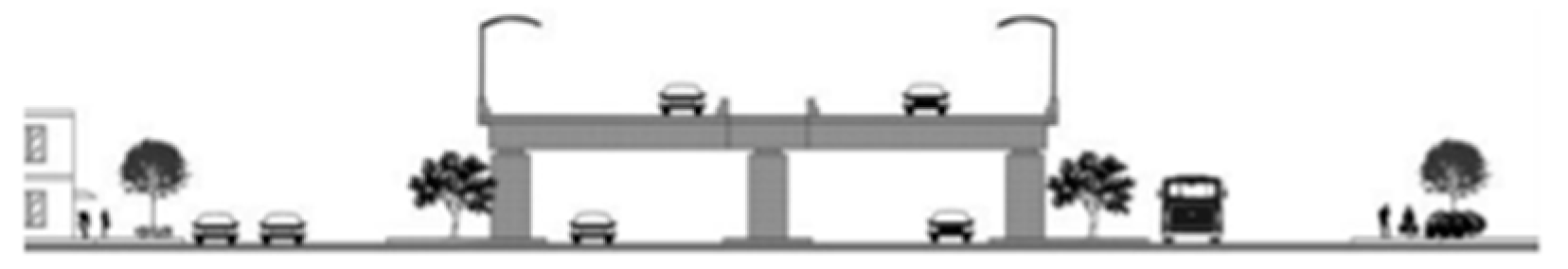

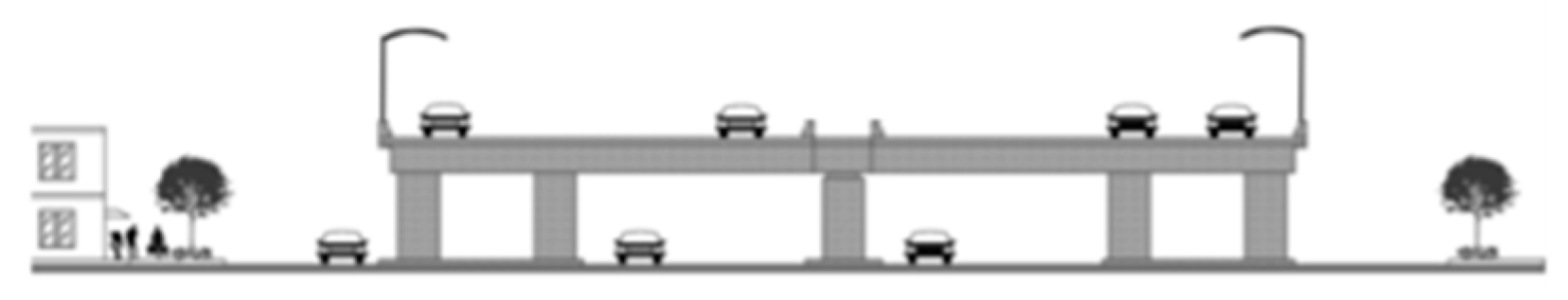

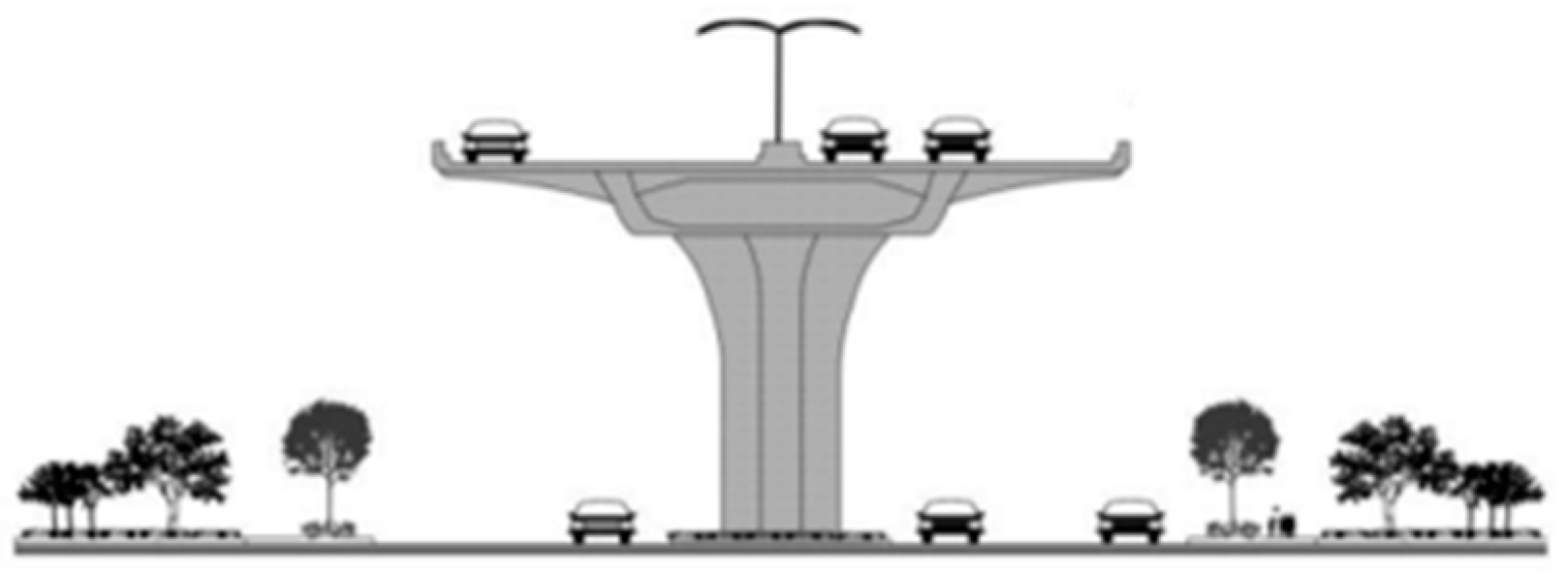

Taichung’s elevated roads were selected to explore the reuse values of the unused space under the bridge in

Figure 1. The elevated bridge of the Taichung Route 74 was constructed with sections under the bridge [

12]. The size of the space under the bridge is presented in

Table 1. Forms 6 and 9 were appropriate for the reuse of the space under the bridge and were investigated using the critical chain method.

2.4. Critical Chain Method

The critical chain method is an extension of the expectancy-values theory. The expectancy-values theory is used to determine the motivation of an individual to accomplish a task using the likelihood of success of the task and the values assigned to the task. A state of tasks affects the consequence of people’s behavior, which is stimulated by motivation [

18]. This state affects the outcome of people’s behavior and explains whether people’s behavior is stimulated by motivation. People’s behavior is determined by the expected outcome that may be achieved by the perception of the behavior and the magnitude of the attraction to the individual [

18]. Therefore, the expected values theory focuses on individual effort–performance linkage, the performance–reward linkage, and the rewards–personal goals relationship. Gutman explored consumer behavior using the expected values theory by integrating product attributes, consumption consequences, and personal values. The critical chain method suggests that product attributes linking to the values at the end of the line are significant to customers [

13] because consumers’ choice is the consequence of using the critical chain method to obtain value from particular attributes. The critical chain method provides a theoretical framework to evaluate the value satisfaction with product attributes and consumer behavior [

27].

To effectively understand consumer values, the critical chain method was used to understand different abstract meanings of each product [

2], exploring the relationship between consumer behavior and values at the following different levels.

Physical objects such as colored pencils, strawberries, or natural landscapes, which can be observed and touched to distinguish it using psychological or physiological characteristics used by consumers.

- 2.

Consequence

A psychological or physiological outcome of a consumer’s desire to consume a product, reflecting the benefits or losses from the experience, such as slow living and cherished objects.

- 3.

Values

Consumers’ behaviors lead to ultimate feelings or goals, such as health and well-being. Olson and Reynolds differentiated concrete and symbolic attributes, functional and psychological consequences, and instrumental and ultimate values. They suggested that consumers’ knowledge of product attributes is linked to their experience and the self-awareness of values at the psychic level [

20].

The critical chain method was developed in marketing and has been widely used to explore the personal values of customer behavior [

24,

28,

29,

30]. Research on the critical chain method focuses on customer and marketing [

26]. It is used to explore the personal needs of regional tourism by exploring the value process acquired by tourists in Hakka cultural tourism [

31]. The tourist experience and value of coastal tourism and leisure zones were explored in the Fishing Resource Conservation Area in Taitung County [

32] and Longshan Temple in Monga [

33]. The behavior of tourism consumers was observed using the critical chain method to deduce the attributes of the space and find its spatial values. We used the critical chain method to understand the behavior of people using the unused space under bridges.

5. Conclusions

As technology advances and the pace of life accelerates, people are increasingly looking for a place to relax and relieve stress in their daily lives, and unused space under bridges, due to its unique geographic and structural characteristics, has become a potential resource for reuse. However, the attributes of the space under bridges are diverse, and its intrinsic values are complex. Therefore, we explored users’ values for the reuse of under-bridge space through interviews and established a reference model for the design of the reuse of under-bridge space by integrating attributes, consequences, and values. The attributes of the under-bridge space included “bridge shelter” and “circular space” with values of sheltering from the sun and rain, while the utilization focuses on “exercise”, “convenience” and “spaciousness”. This result reflects the potential of the under-bridge space as a multi-functional activity area. In addition, the values included “comfort”, “health”, and “fun”, showing that users expected that the design and utilization of the space under the bridge would provide convenience and practical functions for psychological and emotional relaxation. Using the ACV matrix, a value-oriented framework for the reuse of unused space under the bridge was constructed to illustrate its potential values in the urban environment. The results can be used to enhance the efficiency of space utilization and create a new opportunity for interaction between urban landscape and community, increasing possibilities for urban planning and sustainable development.

Previous studies on the reuse of space under bridges focused on the inherent use of space for planning and did not quantify the value of the renovated space to the stakeholders. The study results presented how land and spatial resources can be utilized to improve the public image of the city and to expand the boundary of public life in the city. Using the critical chain method, the attributes were identified for effective spatial planning for the area. The reuse of unused space under the bridge can be fostered based on the attributes of local needs, and the spatial functions must be different from previous plans. The unused space in the city can be reused considering a regional pattern, and the user’s values must be reflected by the subsequent administrators or designers for the space-use planning.

As the existing equipment is mainly for leisure sports, the service content is relatively monotonous. Therefore, various attributes must be considered, and other possibilities for using the space must be diversified. It is also necessary to reuse the unused space under the bridge for commercialization and landscaping.