Abstract

Corporate social responsibility and its communication are practices that have been developed for several years in developed and emerging countries, which have aroused great interest around the world and particularly in Morocco. Therefore, our main objective is to study the impact of ESG disclosure imposed by the market regulator on the extent of corporate commitment. This paper aims to understand one of the factors explaining the CSR commitment of Moroccan companies, namely the regulatory environment. Its main strength lies in the in-depth examination of the current regulatory environment and its real impact on corporate social responsibility strategies and actions. To answer our research question, we conducted an empirical study based on a single hypothesis tested through secondary data processing. The results show that engagement, under institutional pressure, has a positive impact on the annual publication of ESG reports on the CSR engagement of Moroccan companies.

1. Introduction

The social role of companies is being reconsidered, and since the 1990s, they have been obliged to respond to new objectives linked to sustainable development. This underlines the importance of the company as a player, as well as its involvement in CSR issues.

According to the various definitions proposed, CSR refers to environmental and social actions and measures voluntarily put in place by the company and which go beyond legal provisions [1].

The integration of CSR at the heart of business strategy involves the company’s communication with its stakeholders [2]. Its future depends on how the company’s stakeholders perceive its behavior. The communication of a CSR stance is implacably linked to the existence of a responsible attitude or, at least, to having acts of social responsibility to disclose. The level of CSR communication and its reliability are linked to the motivations behind the responsible practices adopted.

While many extra-financial disclosure tools are available, ESG reports remain the most widely used tool, particularly in Morocco, for revealing the social, economic and environmental impact of a company’s activities.

In general, CSR/ESG reports are the most widely used tool for presenting the responsible behavior of companies. Although the determining factors, or even motivations, for these two practices are not disclosed, we believe that, firstly, commitment to extra-financial communication is positively correlated with a company’s responsible commitment. The entity’s responsible actions and practices determine the content and level of reporting.

The national context in this area has undergone a number of changes, notably the development of human development reforms, regulations and policies; the National Initiative for Human Development; the actions put in place by the CGEM, including the development of a CSR Label and Charter; and more recently, the reform of the regulatory and institutional framework for extra-financial communication by publicly traded companies in Morocco.

This is only the first step in explaining our results in relation to the new regulations on extra-financial communication in Morocco, as set out in Circulation N°03/19 on financial operations and information [3].

The main objective of this research work is to identify how the AMMC’s decision to make extra-financial communication mandatory for companies making public offerings impacts the degree of their commitment to CSR.

This objective can be formulated in the form of a main question:

To what extent do the extra-financial reporting requirements set out in Circulation 03/19 on financial transactions and disclosures have an impact on the degree of CSR commitment of companies making public offerings in Morocco?

2. Theoretical Framework of the Research and Formulation of Hypotheses

Several studies [4,5] have sought to identify the factors likely to explain companies’ motivation to publish non-financial information as part of their CSR commitment. Drawing on agency, legitimacy and stakeholder theories, [6,7] have shown that the dissemination of non-financial information responds to economic stimuli, public pressure, or institutional conditions.

The use of a single theoretical perspective cannot fully explain either companies’ behavior in implementing CSR practices or their motivation to publish a certain amount of information regarding how they account for the social and environmental consequences of their activity [8].

Based on the literature on the determinants of social and environmental disclosure, we have identified, among these determinants, the company’s degree of commitment to CSR [5,9,10]. Indeed, the more committed a company is to social and environmental issues, the more material it will have to disclose.

The disclosure of ESG information enables the company to improve its communication with its stakeholders, including investors. This is because companies committed to social and environmental issues attract socially responsible investors, as well as consumers interested in the pillars of CSR [11].

In other words, there is a link between a company’s social and/or environmental performance and the amount of non-financial information it discloses. Entities which perform highly for several aspects of CSR have more information to disclose. Conversely, a company’s weak commitment to CSR could explain the low level of non-financial information disclosed. Accordingly, our work is based on the company’s CSR commitment as a determinant of non-financial disclosure.

We have therefore used this positive link between CSR disclosure and corporate commitment to CSR as the basis for our research hypothesis, which links these two practices in a way that is informed and enriched by the main theories on the subject.

In particular, we focus on the neo-institutional theory, according to which the degree of CSR commitment can be explained by the pressure exerted by the social and institutional environment in which the company operates [6].

Corporate social and environmental commitment does not simply refer to the search for greater efficiency and effectiveness. Rather, it may reflect a desire to please stakeholders, neutralize competitors’ competitive advantages, and acquire greater legitimacy [12]. The adoption of CSR practices can be seen as a response to pressure from stakeholders, including regulatory bodies. Corporate social and environmental disclosures have been analyzed in light of regulations, laws and standards. If, therefore, the company is faced with the obligation to communicate about how it accounts for the social and environmental consequences of its activities, it will focus more efforts on fulfilling its CSR so that it will have material to publish [13].

The adoption of mandatory extra-financial reporting is an instrument of government policy in the field of CSR. It is a regulation that enhances transparency by reducing information asymmetries between companies and their stakeholders [14]. Thus, transparency can lead to an improvement in CSR actions, since companies will expose themselves and compare themselves more easily to other companies, even competitors [15].

The impact of mandatory ESG communication is a central question in organizational research. This impact manifests itself in greater adoption of CSR policies and actions, with minimization or prevention of unethical actions [16,17,18,19,20,21].

As a regulatory body, the AMMC’s decision represents institutional pressure on companies making public offerings in Morocco. It could lead them to make a greater commitment to social and environmental goals in order to improve their publications in this area.

This literature review leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H1.

The regulatory requirement for extra-financial reporting is having a positive impact on companies’ CSR commitments.

3. Materials and Methods

This research is of a descriptive nature, enabling us to describe the various responsible actions undertaken by the companies included in our study. In order to provide an explanation of the current level of CSR commitment among Moroccan companies, we carried out statistical analyses of the evolution of the CSR commitment of different companies.

For the purposes of this study, we opted for content analysis. Content analysis is a tool for assessing the scope of corporate social responsibility activities in a company’s various publications [22].

According to [23], content analysis represents an objective, quantitative and systematic description of what emerges in a communication. In fact, it ensures a quantitative, objective and systematic scientific analysis of data [24]. Reliability and validity are synonymous with all these requirements in terms of objectivity, quantity, generality and systems [25].

To achieve our research objective, we examined the impact of the annual publication of ESG reports, imposed by the regulator, on the CSR commitment of companies making public offerings in Morocco. Our research will therefore be quantitative in nature, based on secondary data processing. The evolution of this commitment represents our variable to be explained, and the explanatory variable will therefore be the annual publication of ESG reports, imposed by the AMMC

For our study, the evaluation of the impact of ESG disclosure on a company’s CSR commitment consists of measuring the degree of CSR commitment of companies over periods prior and subsequent to the AMMC Circulation through which the new regulation was announced, in order to observe its evolution.

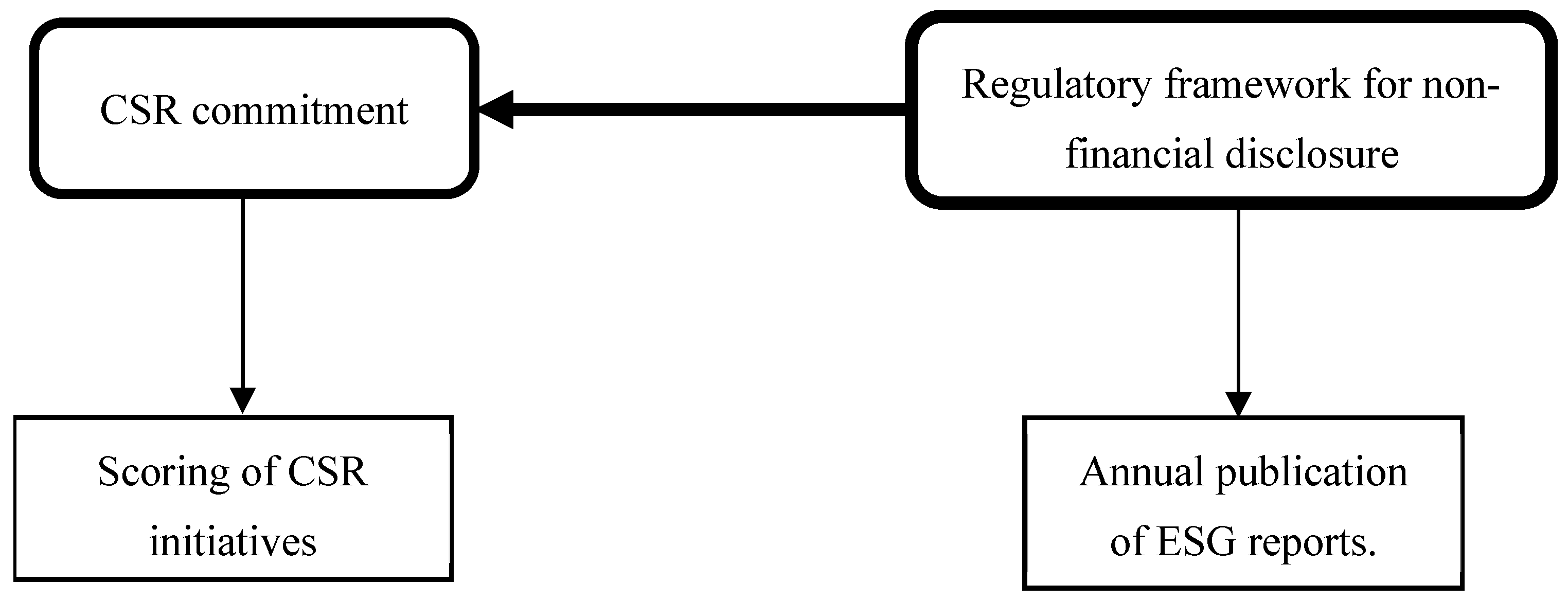

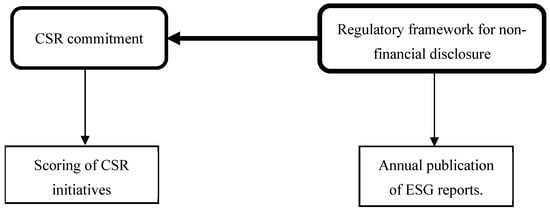

The simplified research model for this study can be presented as follow, Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Research model for the study.

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The sample for our study is made up of companies making public calls in Morocco, the category of companies covered by Circulation n°03/19 on financial operations and information, in which the AMMC expressed its decision to make extra-financial communication compulsory.

We have conducted the study in two different ways, following the divergence observed in the characteristics of our sample. The scope of commitment and maturity in terms of ESG disclosure of the companies studied differ from one entity to another. This is the main criterion for selecting the companies in each sample, as well as for choosing the method used to measure their CSR commitment.

On the basis of the criterion of availability of secondary sources of information on CSR, we can distinguish two profiles of companies making public offerings in Morocco: those voluntarily committed to the publication of ESG reports, having published ESG reports for at least one year prior to the amendment of the aforementioned Circulation, and those that had never published an ESG report prior to the announcement of the new regulations. This distinction led us to set up our two samples, named samples (A) and (B). The first is made up of twenty exhaustively selected companies for which ESG reports are available for our research period, 2018–2022, and cover a period of 5 years. This period covers one year before the new regulations were implemented in February 2019.

The aim is to get an idea of the evolution of companies’ commitment to the new CSR regulations, which were announced in February 2019. The choice of the study period for this first sample is therefore linked primarily to the date of the new regulation on extra-financial communication in Circulation N°03/19, in order to be able to measure its impact on the responsible actions carried out by companies.

The second sample is made up of all Moroccan companies that only published their first ESG reports after becoming legally obliged to do so. For this second category of companies, we were unable to cover the CSR actions implemented during 2018, the year following the new regulations, due to the unavailability of ESG reports, the main source of secondary information in this area, for this financial year.

For sample A, we collected secondary data, mainly from ESG reports published over the period 2018–2022. More specifically, the data was collected on actions taken in each area: social, environmental, and governance actions.

The non-representativeness of this sample (A), due to the divergent characteristics of the population studied, particularly in terms of maturity and commitment to CSR communication, led us to collect a second sample (B). The latter comprises all Moroccan companies that had not published ESG reports prior to the amendment of Circulation n°03/19. For this category of company, it was difficult to measure their CSR commitment using the same method as before, due to the unavailability of extra-financial information and these companies’ lack of maturity in this area compared with other companies. These two factors can distort our results. Our research therefore focused, first and foremost, on their reaction to the new regulations.

Measuring the degree of compliance with AMMC requirements in itself constitutes a responsible commitment on the part of the company. We will apply the same method of analysis to the evolution of CSR commitment carried out on sample A, in order to observe the impact of Circulation N°03/19 on companies’ improvement of their CSR commitment.

3.2. CSR Commitment Analysis Grid

CSR commitment was operationalized through scores calculated by us on the basis of ESG indicators, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indicators to measure CSR commitment.

Based on a theoretical and empirical corpus, we have developed our CSR analysis grid. Conceptually, it is in line with the Triple Bottom Line approach [26], combined with main aspects of CSR [27].

The environmental indicators we mention are inspired by organizational responses to environmental pressures [28]. The social indicators are based on a conceptual model for incorporating CSR into human resource management [29]. The governance component highlights the relationship between good governance and CSR [30].

3.3. Measuring Scales

The companies in this sample show a certain amount of maturity in terms of CSR commitment and communication, which explains our choice to extend the AMMC guidelines to other elements and to use several levels of commitment for each indicator, presented by scales. We calculated commitment scores, giving each of these indicators a rating based on a scale of importance of the actions implemented by the companies.

The scale used is shown at the top of the Table 2 and makes it easier to see how the commitment has evolved, in line with the CSR maturity model [31]. The latter presents CSR commitment as a continuum, ranging from total inactivity (level 0 in our scale) to full strategic integration (level 3).

Table 2.

CSR action measurement scale.

The approach adopted is in line with the methodological tradition established by Wiseman [32] and subsequently refined by Clarkson [33], who have endorsed the validity of a four-level ordinal scale for assessing non-financial disclosures. The level of detail provided by this method allows the different levels of maturity in this area to be accurately represented, while avoiding the credibility problems associated with narrower scales.

An overview of the methodology adopted is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the methodology adopted.

4. Results and Discussion

As already noted, we mobilized secondary data drawn from the ESG reports of the companies studied. The results were used to interpret the level of CSR commitment of these companies, to measure the evolution of this commitment and to conclude, subsequently, the nature of the impact of the AMMC decision on the responsible behavior of the companies concerned by the said decision.

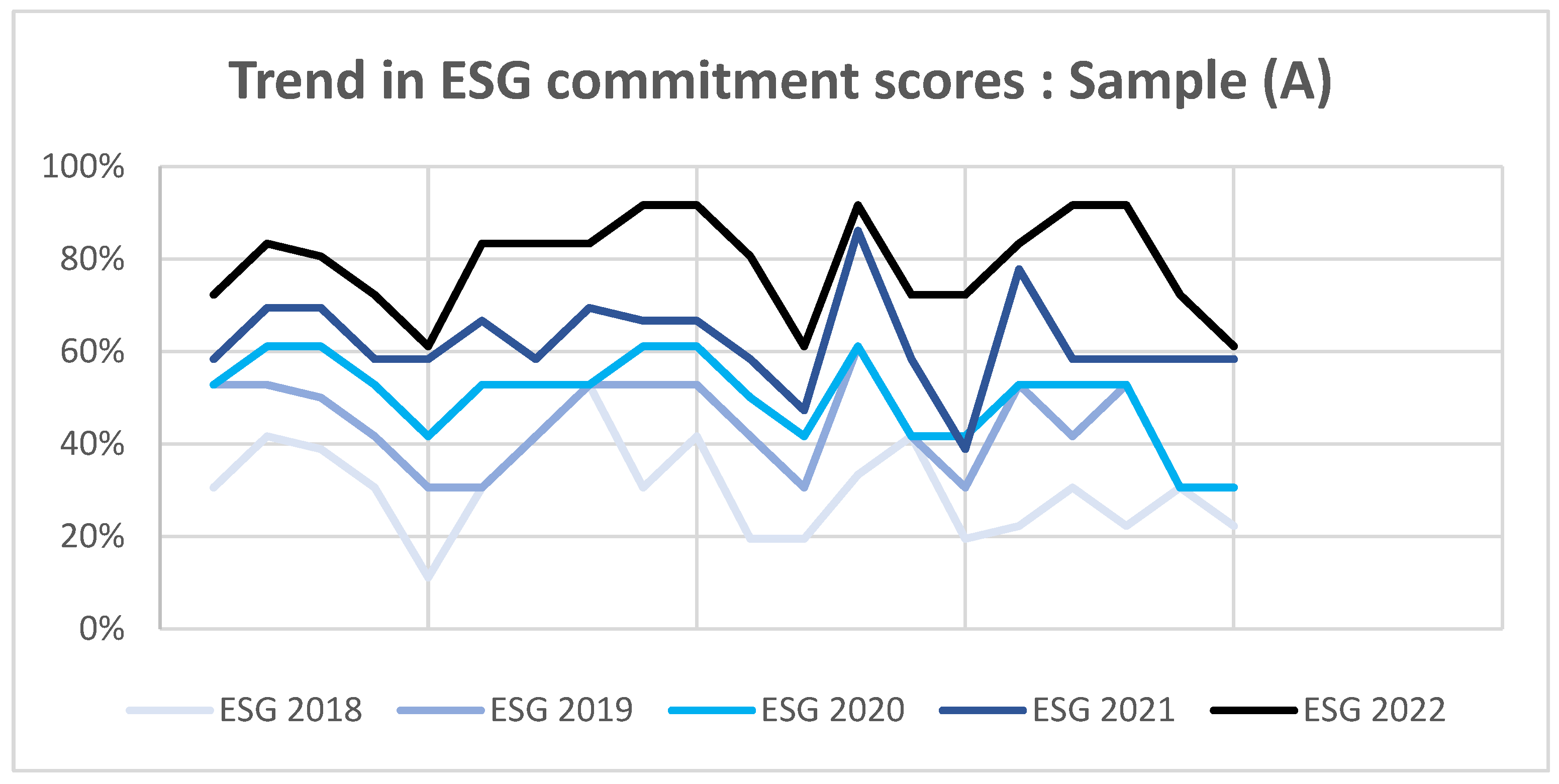

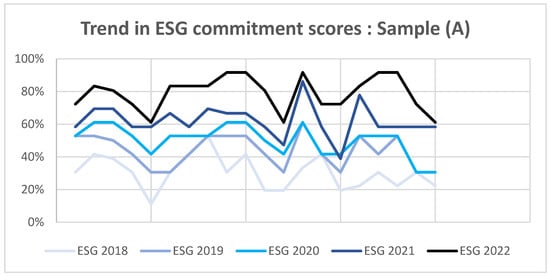

The graph above represents an overall description of the level of responsible commitment of the various companies studied, over the period 2018–2022. For each company, we studied the nature and scope of the actions taken, as communicated in their ESG reports, in order to give each indicator a score. These scores were used to calculate the social, environmental and governance scores presented above, which represent the three components of each company’s total CSR commitment score.

Figure 2 shows the scores calculated over the period studied. The first observation to be made is that the scores for 2018 are relatively low. This is logical, and can be explained by the low maturity of companies in this area. Until this year, there was no regulatory framework for these publications. As a result, the information presented did not meet the necessary requirements. Thereafter, scores continued to improve, reaching good levels in 2022.

Figure 2.

ESG commitment of companies in sample (A).

In the same sub-sample, we noted the difference in practices and levels of action taken by companies. This can be explained by the internal factors of each company, which can themselves impact the scope of CSR actions.

The evolution of the scores calculated varies between 5% and 30%, meaning that the majority of companies have improved their responsible actions, practices and even visions by the same percentage. Calculating this evolution gave us a clear picture of how companies reacted to the new regulations, which represent the only event during the period studied that is likely to have had such an impact. All in all, it can be said that the research period saw a positive evolution in engagement scores across all three strands.

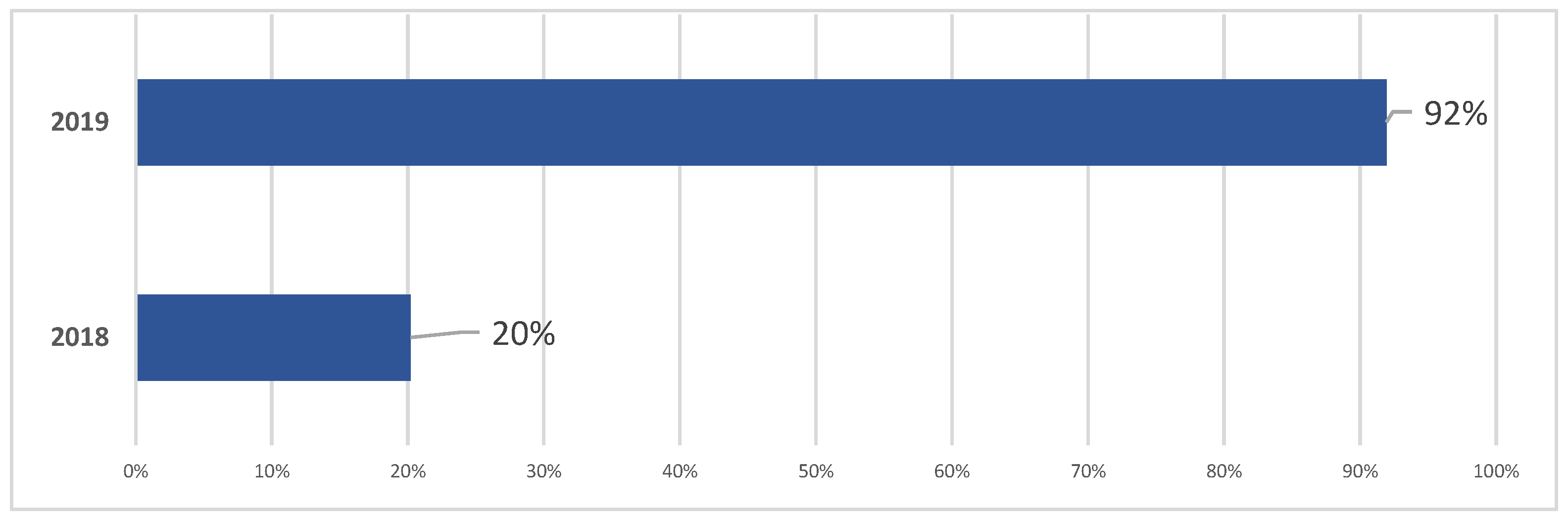

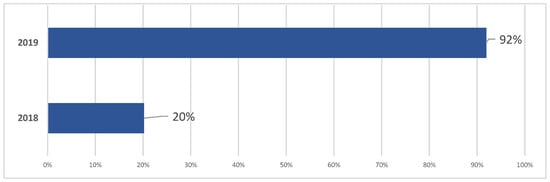

For sample (B), we began by studying companies’ reaction to the new regulations, the results of which are shown above, Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Trend in ESG reporting commitment of companies in sample (B).

The year 2019 saw the publication of ESG reports by almost all the companies affected by Circulation N°03/19. In terms of their reporting, the companies in this sample have shown a high degree of maturity, thanks to their compliance with the AMMC’s guidelines on extra-financial communication, with a high level of transparency. Companies’ compliance with the new regulatory framework, and their commitment to extra-financial communication, in itself represents responsible behavior.

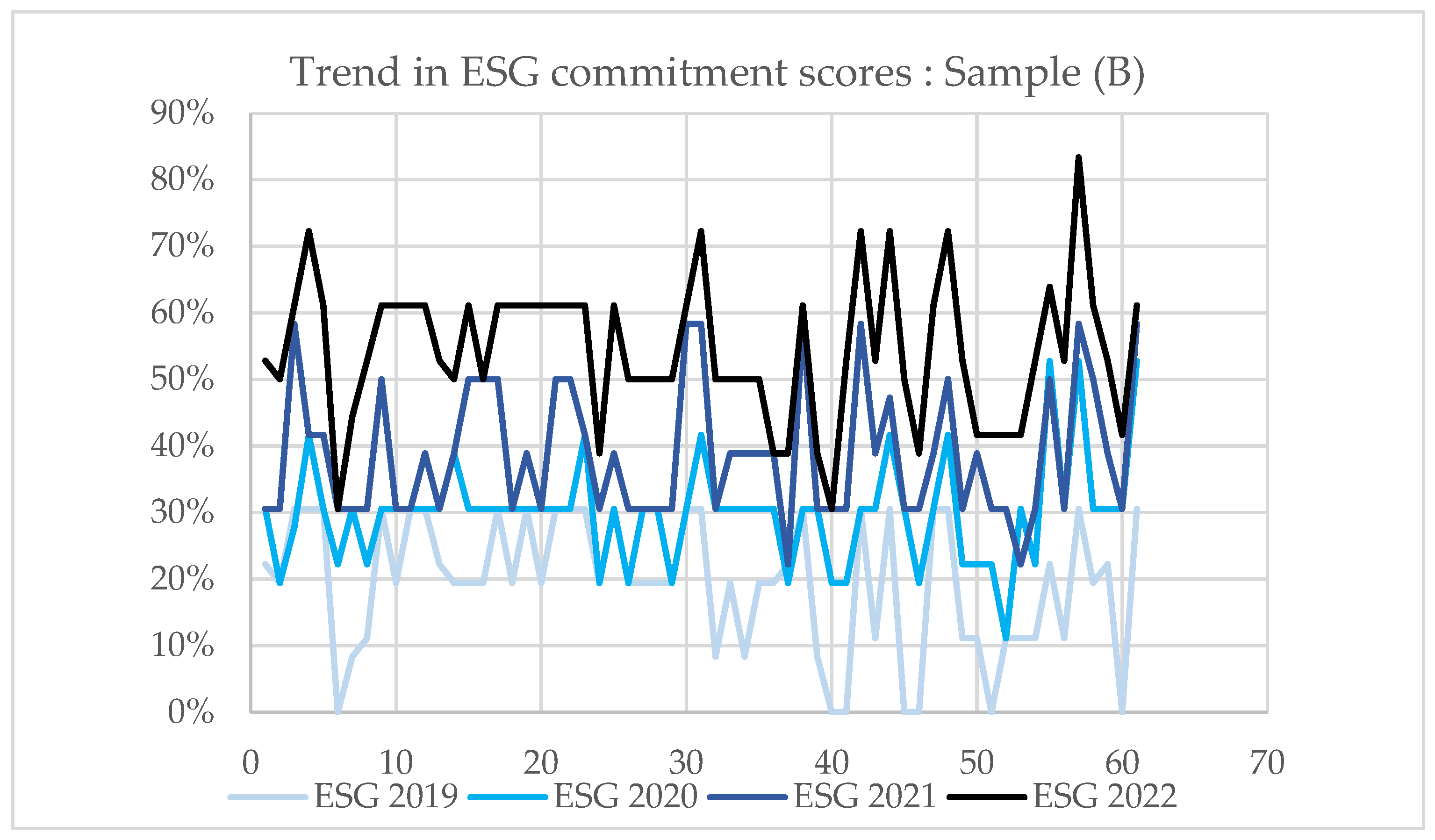

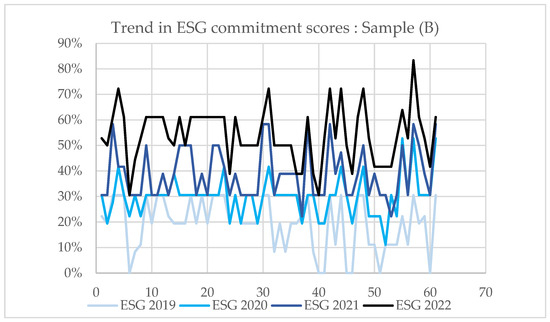

A study of the evolution of the CSR commitment of companies in sample B is represented in the following figure.

The CSR commitment of companies in sample B shows an upward trend. This means that these companies have improved their CSR commitment over the period studied.

Admittedly, the scores for this sub-sample are low compared to the scores for sample A. The latter includes companies that adopted disclosure practices long before regulation, on a voluntary basis. This explains the variation in scores between the two sub-samples.

In the same context, in their first year of ESG disclosure, these companies presented less ESG information. While the evolution may be small, it is noticeable.

Overall, over the four years of annual reporting, we can see that these companies have acquired greater maturity, with more efforts in this area. After companies making public offerings in Morocco were required to publish their ESG report annually, they began to familiarize themselves with CSR issues, which led to a steady increase in their ESG scores.

The analysis of the data shows a positive but nuanced influence of regulatory obligations on the social responsibility commitments of Moroccan companies. An analysis of the two groups clearly shows that companies that already had an ESG culture (sample A) have made a greater and more consistent systematic commitment (60–90%) than those that adopted these approaches as a result of a legal obligation (sample B), whose commitment generally fluctuates between 20% and 60%, with pronounced volatility. However, there is a general increase between 2019 and 2022 for both groups, with the best results recorded in 2022 for each of the samples.

The examination of the data strongly supports the idea that legal obligations for non-financial reporting have a positive impact on companies’ CSR initiatives. This correlation is particularly evident in the increase in scores for Group B, as shown in Figure 4, which consists of companies that have adopted ESG practices as a result of a legal obligation. This notable progress between 2019 and 2022 was achieved despite a high degree of volatility.

Figure 4.

ESG commitment of companies in the sample (B).

5. Discussion

As corporate social responsibility practices develop around the world, a significant debate has emerged regarding the most effective way to regularize CSR activities as well as the role of government [31,32]. This paper focuses on mandatory ESG disclosure as a means of enhancing the transparency of corporate social responsibility activities. We analyze the consequences of mandatory ESG disclosure for the rigor or complacency of corporate social responsibility activities.

We find that legally mandated ESG communication is likely to lead to an increase in CSR practices, validating our research hypothesis H1.

All in all, the scope of regulation increasing to include the mandatory publication of ESG information is likely to increase companies’ adoption of CSR. These results are in line with previous studies, which have confirmed this [33,34]. ESG reports focus mainly on CSR actions implemented by companies. This means that CSR practices are major elements on which this communication focuses, and so strengthening this communication is strongly linked to improving CSR practices.

As companies are required to disclose certain types of activities, or as they compare their disclosed activities with those of competing companies, the adoption of CSR will tend to increase the scope of CSR activities in more areas [35].

Institutional and stakeholder perspectives can explain the results of our research by highlighting the positive impact of ESG regulations on the CSR commitment of Moroccan companies. This positive impact can be rooted in stakeholder theory [36]. In this case, ESG regulation is a tool for structuring societal expectations. This structuring consists of transforming the more or less implicit expectations of stakeholders into explicit and quantifiable needs. It is a kind of formalization that encourages companies to adopt a more strategic and rigorous approach to CSR in order to meet the demands of all stakeholders.

From an institutional point of view [37], ESG regulation has, in our case, enabled the creation of a coercive isomorphism mechanism. As a result, companies begin to implement comparable CSR approaches in response to regulatory constraints. It also generates normative and mimetic isomorphism as they integrate organizational norms and imitate the practices of industry leaders.

This two-pronged impact process explains our findings. Regulation no longer simply ensures compliance, but also has a profound impact on organizational behavior. The complementary combination of these two theories explains how the regulation of ESG communication by Moroccan companies has triggered a dynamic process in which institutional pressure and responsiveness to stakeholder expectations are mutually reinforcing.

In conclusion, we can say that institutional pressure was effective in producing an effect, not only on the extra-financial communication of Moroccan companies, but above all on their responsible behavior, which is highlighted differently according to the characteristics of each company. This responsible behavior, which represents the constructive element of extra-financial communication, is a means of signaling, without which ESG disclosure cannot be proposed.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we analyze the impact of changes to the regulatory framework for non-financial communication on the CSR commitment of Moroccan companies. In 2019, the Moroccan capital markets authority amended Circulation N°03/19 pertaining to operations and financial information, which mainly introduced the new mandatory nature of non-financial communication. This decision concerned all publicly trading companies in Morocco, divided into two categories according to the availability of ESG reports prior to the date of amendment of the Circulation.

After briefly presenting the context and theoretical framework of the research, the study focused on two samples of companies, according to the characteristics of each, to begin data collection and analysis.

Our study is quantitative in nature, based on the processing of secondary data drawn mainly from ESG reports. The information collected was analyzed, using indicators and measurement scales, to calculate commitment scores for each of the companies whose progress was positive. Companies for which publication of ESG reports was not voluntary were first analyzed in terms of their behavior in the face of the new regulations. This was followed by a study of their CSR commitment. The CMMA’s decision had an impact on both categories of companies, which demonstrated their commitment, but each in their own way, consistent with their characteristics and level of maturity in this area.

In conclusion, this research makes an important contribution to understanding the complex relationship between the regulatory framework for ESG communication and the responsible engagement of Moroccan companies. Our analysis adds value by scrutinizing the evolving regulatory environment and highlighting its crucial impact on the evolution of CSR approaches. Our findings suggest that the frameworks shaping the regulatory environment not only aim to standardize ESG disclosure, but also influence the way companies develop and implement their CSR strategies.

This perspective enriches the literature and provides professionals with the interpretive tools they need to navigate an ever-changing regulatory context, where compliance with standards can prove to be a vector for innovation and sincerity in social commitment.

The conduct of any academic research faces various limitations, both theoretical and methodological. As a result, the first obstacle we encountered was that linked to the collection of information, especially with the use of secondary data which was not sufficient to carry out the study on the entire population concerned by the study. This may lead to other avenues of research on the same issue, but using primary data sources and working over a longer study period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.O. and Asdiou abdelkarim.; methodology, E.A.O. and A.A.; software, E.A.O.; validation, E.A.O. and A.A.; formal analysis, E.A.O.; investigation, E.A.O.; resources, E.A.O.; data curation, E.A.O. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.O. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, E.A.O. and A.A.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMMC | Moroccan Capital Market Authority. |

| CGEM | General Confederation of Moroccan companies. |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility. |

| ESG | Environmental, Social and governance. |

References

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Theory of the Firm Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, B.; Casey, R.J.; Grenier, J.H.; Heitger, D.L. Exploring the Strategic Integration of Sustainability Initiatives: Opportunities for Accounting Research. Account. Horiz. 2012, 26, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circulaire 03_19 Relative aux Opérations et Informations Financières.pdf. Available online: https://www.ammc.ma/sites/default/files/Circulaire%2003_19%20relative%20aux%20op%C3%A9rations%20et%20informations%20financi%C3%A8res.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Masum, M.H.; Latiff, A.R.A.; Osman, M.N.H. Determinants of corporate voluntary disclosure in a transition economy. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2021, 18, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Rahman, R.; Alsayegh, M.F. Determinants of corporate environment, social and governance (ESG) reporting among Asian firms. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M.; Van Velthoven, B. Environmental disclosure quality in large German companies: Economic incentives, public pressures or institutional conditions? Eur. Account. Rev. 2005, 14, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamahros, H.M.; Alquhaif, A.; Qasem, A.; Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Thomran, M.; Al-Duais, S.D.; Shukeri, S.N.; Khojally, H.M.A. Corporate Governance Mechanisms and ESG Reporting: Evidence from the Saudi Stock Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanajongkol, S.; Davey, H.; Low, M. Corporate social reporting in Thailand: The news is all good and increasing. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2006, 3, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Dong, Y.; Ni, C.; Fu, R. Determinants and economic consequences of non-financial disclosure quality. Eur. Account. Rev. 2016, 25, 287–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Quina-Custodio, I.A. Disclosure of corporate social responsibility information and explanatory factors. Online Inf. Rev. 2016, 40, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, S.S.; Ferreri, L.B.; Parker, L.D. The impact of corporate characteristics on social responsibility disclosure: A typology and frequency-based analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 1987, 12, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of socialand environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D. The Kasky-Nike Threat to Corporate Social Reporting: Implementing a Standard of Optimal Truthful Disclosure as a Solution. Bus. Ethics Q. 2007, 17, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Spena, T.; Tregua, M.; De Chiara, A. Trends and Drivers in CSR Disclosure: A Focus on Reporting Practices in the Automotive Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 151, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strike, V.; Gao, J.; Bansal, T. Being Good While Being Bad: Social Responsibility and the International Diversification of Us Firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Mueller, K. The CSR Bottom Line: Preventing Corporate Social Irresponsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1928–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, S.; Mostafa, A.M.S.; Wang, X. Participative Leadership and Organizational Identification in SMEs in the MENA Region: Testing the Roles of CSR Perceptions and Pride in Membership. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, D.; Cui, D.; Ma, X. Environmental, social, governance disclosure and corporate sustainable growth: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1015764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F.; Aragon-Correa, J.A. Greenwashing in Corporate Environmentalism Research and Practice: The Importance of What We Say and Do. Org. Environ. 2014, 27, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, T.; Egels-Zandén, N. Beyond Decoupling: Unions and the Leveraging of Corporate Social Responsibility in Indonesia. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2015, 14, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L.; Wood, R.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FELICIANO. Some Uses of Content Analysis in Social Research on JSTOR. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41853539 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Kassarjian, H.H. Content Analysis in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.F.; Monsen, R.J. On the Measurement of Corporate Social Responsibility: Self-Reported Disclosures as a Method of Measuring Corporate Social Involvement. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 22, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line. Available online: https://johnelkington.com/archive/TBL-elkington-chapter.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational Responses to Environmental Demands: Opening the Black Box. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=994893 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Voegtlin, C.; Greenwood, M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatotchev, I.; Nakajima, C. Corporate Governance, Responsible Managerial Behavior, and Corporate Social Responsibility: Organizational Efficiency Versus Organizational Legitimacy? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinderman, D. “Free us up so we can be responsible!” The co-evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility and neo-liberalism in the UK, 1977–2010. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2012, 10, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.S.; Moon, J. Visible Hands: Government Regulation and International Business Responsibility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-107-10490-7. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.; Marais, M. A Multi-level Perspective of CSR Reporting: The Implications of National Institutions and Industry Risk Characteristics. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2012.00926.x (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Chelli, M.; Durocher, S.; Fortin, A. Normativity in Environmental Reporting: A Comparison of Three Regimes. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Hung, M.; Wang, Y. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Belfast, UK, 1984; ISBN 978-0-273-01913-8. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).