Abstract

Glaucoma is a highly perilous ocular disease that significantly impacts human visual acuity. This is a retinal condition that causes damage to the Optic Nerve Head (ONH) and can lead to permanent blindness if detected in a late stage. The prevention of permanent blindness is contingent upon the timely identification and intervention of glaucoma during its initial stages. This paper introduces a convolutional neural network (CNN) model that utilizes specific architectural designs to identify early-stage glaucoma by analyzing fundus images. This study utilizes publicly accessible datasets, including the Online Retinal Fundus Image Database for Glaucoma Analysis and Research (ORIGA), Structured Analysis of the Retina (STARE), and Retinal Fundus Glaucoma Challenge (REFUGE). The retinal fundus images are fed into AlexNet, VGG16, ResNet50, and InceptionV3 models for the purpose of classifying glaucoma. The ResNet50 and InceptionV3 models, both of which demonstrated a superior performance, were merged to create a hybrid model. The ORIGA dataset achieved high accuracy with an F1 Score of 97.4%, while the STARE dataset achieved higher accuracy with an F1 Score of 99.1%. The REFUGE dataset also showed excellent performance, with an F1 Score of 99.2%. The proposed methodology has established a reliable glaucoma diagnostic system, aiding ophthalmologists and physicians in conducting accurate mass screenings and diagnosing glaucoma.

1. Introduction

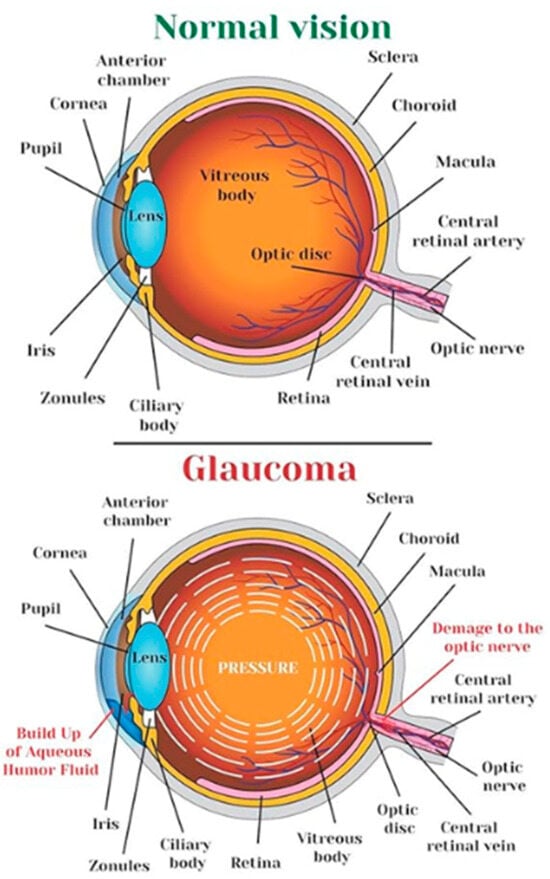

The eye, a sensory organ of the visual system, reacts to light and facilitates the perception of visual stimuli. The optic nerve, a distinct region responsible for visual perception, efficiently transmits visual information from the retina to the visual cortex in the brain. Glaucoma, a prevalent ocular condition, has increased in prevalence due to elevated intraocular pressure. This damage can cause vision impairment and the disruption of blood circulation, leading to ocular conditions like glaucoma. In Figure 1, a schematic diagram of a typical human eye and a diseased eye affected by glaucoma is provided [1].

Figure 1.

Human eye and an eye affected by glaucoma [1].

Glaucoma is an ocular condition characterized by the gradual deterioration of the optic nerve due to increased intraocular pressure [2]. The global cumulative cases are projected to reach 111.8 million by 2040, with those of Asian descent making up 47% of the affected individuals and 87% of those affected by Angle Closure Glaucoma [3]. Individuals over 60 years old are more susceptible to the condition [4]. Glaucoma is the second most prevalent factor contributing to visual impairment globally, and early detection is crucial to prevent irreversible vision loss and structural damage [3].

Glaucoma is a condition characterized by two main types: open-angle glaucoma and angle-closure glaucoma. Open-angle glaucoma is a prevalent form with no noticeable symptoms and is prevalent in 90% of the total glaucoma patient population [5]. Angle-closure glaucoma is a significant ocular condition that requires immediate medical intervention. This can cause ocular discomfort, elevated intraocular pressure, cephalalgia, ocular erythema, ocular inflammation, and visual impairment. The treatment options include pharmaceutical interventions and surgical procedures. A routine checkup includes five standard glaucoma tests: tonometry, ophthalmoscopy, perimetry, gonioscopy, and pachymetry. Tonometry measures the intraocular pressure, ophthalmoscopy assesses optic nerve morphology and pigmentation, perimetry measures the visual field, gonioscopy examines the eye angle, and pachymetry evaluates the cornea thickness.

2. Related Work

Glaucoma diagnosis is often based on clinical parameters, like the Cup-to-Disc Ratio (CDR) [6], Rim-to-Disc Area ratio (RDAR) [7], and disc diameter [8]. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) is the most used. A higher CDR increases the likelihood of developing glaucoma, while a lower CDR decreases it. Accurate segmentation of the optic disc and optic cup is necessary for CDR measurement, and three-dimensional Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) can quantify these dimensions [9]. However, OCT is expensive, so many medical practitioners still use fundus images for diagnostic purposes [10]. Techniques like boundary detection, region segmentation, and color and contrast thresholding are widely used [11].

Deep learning methodologies are increasingly used for large-scale population screening and computer vision challenges in medical image processing, speech recognition, pattern recognition, and natural language processing. These techniques efficiently process large volumes of data, including images, text, and sound. Deep neural networks have been successful in real-world problems since 2012, including biomarker segmentation, lesion segmentation, image synthesis, and disease detection. They are increasingly used in medicine for diagnosing glaucoma. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are widely used for image categorization, with a streamlined architecture consisting of convolutional filters, pooling layers, and fully connected layers for classifier development.

One study identifies glaucoma using random forest classification on a private dataset, with a 93% AROC. Compared to stepwise model selection, LASSO, and ridge models, the suggested model outperforms the others, with AROCs of 89.6% and 89.2%, respectively [12]. Angle Closure Glaucoma is assessed using the MultiContext Deep Network (MCDN) using the AS-OCT dataset. Data augmentation increases the amount of training data. Combining the clinical factors improves performance. Tensorflow and the VGG-16 classification model are used for implementation. This research achieved 89.26% accuracy, 0.9456 AUC, 88.89% sensitivity, and 89.63% specificity [13].

Hu et al. [14] introduce a segmentation network using encoder–decoder architecture and attention mechanisms. The network uses a multi-scale weight-shared attention module and a densely connected depth-wise separable convolution module to integrate multi-scale object detection and classification features. The multi-scale weight-shared attention module is strategically placed at the encoder’s uppermost stratum. The final layer uses a depth-wise separable convolution module. The “Aggregation Channel Attention Network” semantic segmentation model proposed by Baixin et al. [15] uses contextual information and a sophisticated encoder–decoder structure. It uses a DenseNet pre-trained submodel and an attention mechanism to manage fundamental attributes, while maintaining spatial data integrity. The model also uses a categorization framework and cross-entropy information to enhance the network performance. Early glaucoma diagnosis is crucial for preventing blindness. Automated retinal image-based systems have been established, but further investigation is needed. The current algorithms require vast datasets, making them difficult to access due to time-consuming training techniques.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Setup

The proposed architectures are implemented using Python software 3.12 on a computer with an Intel Core i7-2.8 GHz CPU and 16 GB of RAM.

3.2. Database

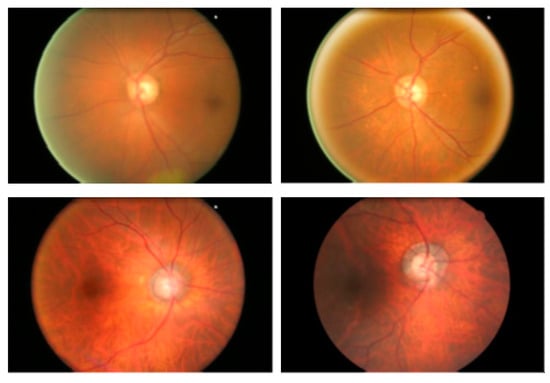

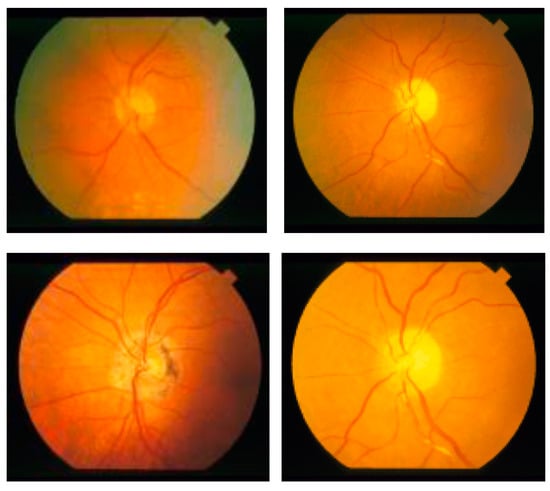

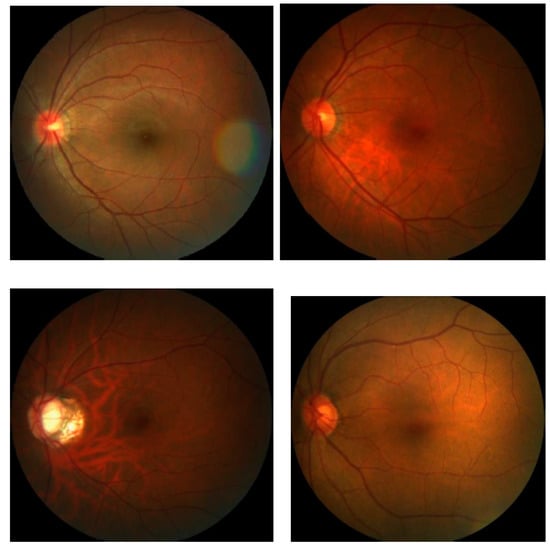

Researchers have used various datasets, including ORIGA, STARE, RIM-1 r2, and DRIVE, to study retinal diseases [16]. This research uses the publicly available datasets ORIGA, STARE, and REFUGE for training and testing the model. A total of 70% of the dataset is allocated for training, while 30% is allocated for testing. The ORIGA dataset contains 650 retinal images, comprising 482 images of healthy retinas and 168 images of retinas affected by glaucoma, as in Figure 2, while the STARE dataset has 50 images of glaucoma and 31 images of normal eye conditions (shown in Figure 3). The REFUGE dataset has 1200 retinal images, including 1080 healthy and 120 affected retinas images, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 2.

ORIGA dataset retinal fundus images.

Figure 3.

STARE dataset retinal fundus images.

Figure 4.

REFUGE dataset retinal fundus images.

3.3. Propose Methodology

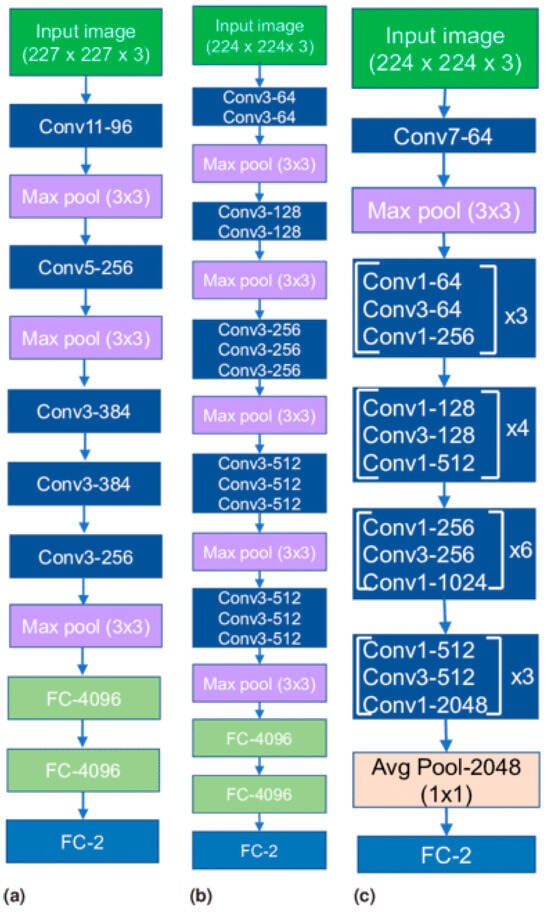

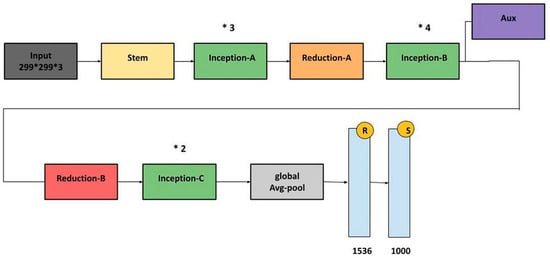

Recent advancements in deep learning, especially in medical image classification, offer promising opportunities for the application of various deep convolutional neural network (CNN) frameworks [17]. Training a CNN can be challenging, but transfer learning methodologies can accelerate data training and reduce the sample quantity [17]. The newly trained model can effectively use information from the pre-existing model [18]. This study evaluates seven baseline models, including AlexNet, VGG16, ResNet50, and InceptionV3, based on their proven efficacy in computer vision, which are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. Transfer learning models are used for implementation, ensuring the output layer aligns with the number of classes used. This study provides detailed discussions on each model.

Figure 5.

Transfer learning architectures: (a) AlexNet, (b) VGG16 and (c) ResNet50.

Figure 6.

InceptionV3 architecture.

3.3.1. AlexNet

The AlexNet architecture is a groundbreaking deep convolutional neural network model known for its efficacy in image classification and recognition tasks. Despite limitations due to hardware constraints, the model is trained using two NVIDIA GTX 580 GPUs, overcoming these limitations. The architecture consists of five convolutional layers, three pooling layers, and three fully connected layers, with approximately 60 million trainable parameters. This approach effectively exploits the potential of deep convolutional neural networks in the 21st century [19,20].

3.3.2. VGG16

The VGG Net, a deep convolutional neural network architecture developed by the Visual Geometry Group at the University of Oxford, has shown exceptional performance in the ILSVRC 2014 object localization and classification competitions [21]. This architecture uses multiple diminutive kernels instead of a solitary expansive kernel for computer vision tasks, potentially improving its precision. The VGG Net is widely used in computer vision applications, particularly in medical imaging, to extract profound image features for further processing.

3.3.3. ResNet50

ResNet frameworks aim to mitigate network performance degradation caused by the vanishing gradient problem by stacking convolutional and pooling layers. Identity shortcut connections bypass one or more layers, while residual blocks maintain identity relationships [22]. This approach effectively reduces training errors in deep architectures. ResNet50, a 50-layer variation, is a popular example.

3.3.4. InceptionV3

The InceptionV3 designs address inconsistent image positioning by assimilating multiple kernel types, expanding network capabilities. The Inception modules enable multiple kernels to operate simultaneously. The InceptionV2 and InceptionV3 architectures address representational bottlenecks and auxiliary classifiers, including kernel factorization and batch normalization [23]. The InceptionV3 architecture won second place in the ILSVRC 2015 image classification evaluation [24].

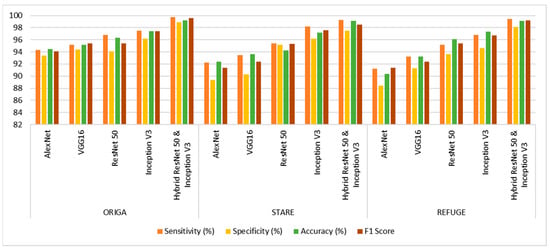

4. Results and Discussion

Performance analysis is used to evaluate the structures, resulting in a complete collection of observations that have been rigorously arranged and collated, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 7. Examining the tabular data shows that the ORIGA dataset produced remarkable results. A maximum accuracy of 99.2%, sensitivity of 99.7%, specificity of 98.9%, and F1 Score of 97.4% are achieved. The STARE dataset has a superior classification accuracy of 99.1%. It has excellent sensitivity (99.3%) and specificity (97.5%). An excellent performance was achieved with the REFUGE dataset. The greatest accuracy is 99.1%, while the F1 Score is 98.5%, indicating good classification precision. Additionally, the sensitivity, which assesses positive occurrence identification, is 99.4%. The specificity, which measures the ability to recognize negative occurrences, is 98.1%, with an F1 Score of 99.2%. The REFUGE dataset is handled effectively and reliably using the employed approach.

Table 1.

Performance evaluation of various transfer learning models.

Figure 7.

Performance analysis graph of the proposed model.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

This study aims to develop a unique glaucoma classification model to enhance medical diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, contributing to the early detection of this ocular condition, thereby improving the efficiency of medical diagnosis. The ORIGA dataset achieved high accuracy, with an F1 Score of 97.4%, while the STARE dataset achieved higher accuracy, with an F1 Score of 99.1%. The REFUGE dataset also showed an excellent performance, with an F1 Score of 99.2%. This proposed methodology has established a reliable glaucoma diagnostic system, aiding ophthalmologists and physicians in conducting accurate mass screening and diagnosing glaucoma.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K.D.; methodology, M.D.N.; software, M.G.; validation, V.K.D. and M.D.N.; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, M.G. and K.S.; resources, S.K.R.; data curation, M.D.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K.D.; writing—review and editing, V.K.D. and M.D.N.; visualization, V.K.D.; supervision, V.K.D.; project administration, V.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vinayaka Mission’s Kirupananda Variyar Engineering College, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation Deemed to be University, Salem, Tamil Nadu, India, for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- A-Websolutions.com. Glaucoma Treatment in Ghatkopar, Mumbai. Available online: https://clearsight.co.in/glaucoma.php (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Zedan, M.J.M.; Zulkifley, M.A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Moubark, A.M.; Kamari, N.A.M.; Abdani, S.R. Automated Glaucoma Screening and Diagnosis Based on Retinal Fundus Images Using Deep Learning Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, H.A.; Broman, A.T. The Number of People with Glaucoma Worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Sample, P.A.; Zangwill, L.M.; Schuman, J.S. Diagnostic tools for glaucoma detection and management. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2008, 53, S17–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veena, H.N.; Muruganandham, A.; Kumaran, T.S. A review on the optic disc and optic cup segmentation and classification approaches over retinal fundus images for detection of glaucoma. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Bergua, A.; Schmitz–Valckenberg, P.; Papastathopoulos, K.I.; Budde, W.M. Ranking of optic disc variables for detection of glaucomatous optic nerve damage. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 41, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, J.B.; Aung, T.; Bourne, R.R.; Bron, A.M.; Ritch, R.; Panda-Jonas, S. Glaucoma. Lancet 2017, 390, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancox, M.D. Optic disc size, an important consideration in the glaucoma evaluation. Clin. Eye Vis. Care 1999, 11, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Niemeijer, M.; Garvin, M.K.; Kwon, Y.H.; Sonka, M.; Abramoff, M.D. Segmentation of the optic disc in 3-D OCT scans of the optic nerve head. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2010, 29, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, J.D.; Sivaswamy, J.; Krishnadas, J.L. Optic Disk and Cup Segmentation from Monocular Colour Retinal Images for Glaucoma Assessment. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2011, 30, 1192–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazroa, A.; Burman, R.; Raahemifar, K.; Lakshminarayanan, V. Optic Disc and Optic Cup Segmentation Methodologies for Glaucoma Image Detection: A Survey. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 2015, 180972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaoka, R.; Hirasawa, K.; Iwase, A.; Fujino, Y.; Murata, H.; Shoji, N.; Araie, M. Validating the usefulness of the “random forests” classifier to diagnose early glaucoma with optical coherence tomography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 174, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Xu, Y.; Lin, S.; Wong, D.W.; Mani, B.; Mahesh, M.; Aung, T.; Liu, J. Multi-context Deep Network for Angle-Closure Glaucoma Screening in Anterior Segment OCT. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Chen, X.; Meng, Q.; Song, J.; Luo, G.; Wang, M.; Shi, F.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, D.; Pan, L.; et al. GDCSeg-Net: General Optic Disc and Cup Segmentation Network for Multi-Device Fundus Images. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 12, 6529–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, B.; Liu, P.; Wang, P.; Shi, L.; Zhao, J. Optic Disc Segmentation Using Attention-Based U-Net and the Improved Cross-Entropy Convolutional Neural Network. Entropy 2020, 22, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virbukaitė, S.; Bernatavičienė, J. Deep Learning Methods for Glaucoma Identification Using Digital Fundus Images. Balt. J. Mod. Comput. 2020, 8, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Wang, D. A Survey of Transfer Learning; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, B.A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2012, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.Q.; Abdulla, H.K.; Ahmed, Z.S.; Surameery, N.M.S.; Rashid, R.D. Modified AlexNet Convolution Neural Network for Covid-19 Detection Using Chest X-ray Images. Kurd. J. Appl. Res. 2020, 5, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Shlens, J. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).