Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate the factors that impact millennials’ intentions to visit green hotels in India and their willingness to participate in the sustainable practices offered by hoteliers. The main objective is to find antecedents of intentions that drive people to visit green hotels using the theory of planned behavior (TPB). This study will focus on millennials as they represent a major part of the consumption economy, having higher disposable income. A preliminary study was conducted using a questionnaire survey, and 35 responses were received. Structural equation modeling was performed to analyze the relationships. Measurement model analysis was performed to validate the instrument and structural model analysis was conducted for hypothesis testing. Collected data were analyzed using SmartPLS V4.0. Findings revealed that subjective norms have a significant impact on customers’ attitude (β = 0.374, p < 0.001) but not much influence on perceived behavioral control (β = 0.218, p > 0.1). Customers’ attitude (β = 0.609, p < 0.001) was found to significantly influence their green purchase intention; PBC (β = 0.242, p > 0.1) did not influence customer’s green purchase intention. Findings also confirmed that attitude is a crucial variable impacting customers’ green purchase intention to visit green hotels. Having a favorable attitude toward saving the environment will have a positive influence on customers’ intention to select a green hotel. This study highlights the factors impacting millennials’ intention to visit green hotels i.e., attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. The study’s findings can be put to use by hoteliers to design sustainable strategies to build environmentally viable hotels and create awareness among the millennial generation to contribute towards sustainable tourism. This can also be utilized to gain a competitive advantage for hotels to market them as a differentiating factor in the highly competitive tourism industry. The government can utilize the findings to develop sustainable infrastructure for protecting the environment.

1. Introduction

Due to the result of growing concern over problems associated with environmental issues like pollution, global warming, and consumption of non-renewable sources, consumers are actively seeking sustainable solutions [1]. This change has compelled organizations to reconsider their business operations and develop innovative and sustainable methods of operating business [2]. Hotels’ impact on environmental degradation is immense due to the great amount of energy consumption of heat, light, and power to provide comfortable services to guests [3]. The travel and tourism industry and environmental impact are directly proportional to each other [4]. As the popularity of a destination increases, the footfall of tourists increases, and this increase in inflow directly impacts the environment negatively [5]. Hence, it is crucial to balance natural resource consumption by tourist activity and preserving ecological resources [6]. Two words have become the Bible of the hospitality industry these days, “sustainability” and “green”, and customers are interested to know the sustainable and innovative practices hotel establishments are following to safeguard the environment [7]. Hence it is becoming vital for hoteliers to understand the importance of sustainable practices in analyzing customers’ purchase decisions [8]. Witnessing this change, concerned authorities in the hospitality industry are occupied with identifying sustainable strategies and communicating the same to customers for perceived benefits [9]. However, customers need to be informed clearly of the concepts of sustainable hotels and what benefits he/she will derive when choosing to stay in such hotels [10].

Huiying Hou et al. [11] describe green hotels as “environmentally friendly properties whose managers are eager to institute programs that save water, save energy, and reduce solid waste–while saving money–to help protect our one and only Earth.” Common best practices followed by green hotels are energy-saving procedures, solid waste management, water conservation, energy-saving lights, etc. [12]. A green hotel must sincerely practice environmental protection and management by following sustainable business operations, thereby reducing the impact on the environment [13]. Recently in India, LEED-certified hotels have gained attention. Starting from the construction of the hotel to the usage of regional goods, the use of wind turbines, and the installation of solar panels, etc. LEED standards are being followed.

Academicians, researchers, and marketing professionals are interested in identifying the factors that impact customers’ intentions to purchase green products. Many researchers have explored their study’s antecedents influencing customer green purchase intention and behavior [13]. However, limited studies were focused on customer response toward sustainable products in the Indian context [14]. An empirical justification of the customer’s intention to stay at a green hotel is required and the factors that influence the intention need to be analyzed. To determine the elements influencing Indian customers’ intention to stay at green hotels, this study is required.

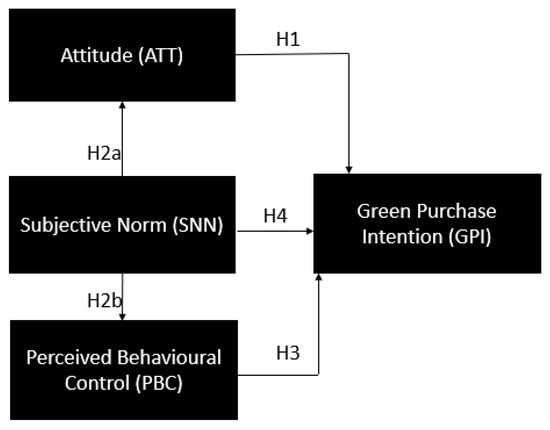

This study will be using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as it has been highly recommended for determining consumer intention and behavior, particularly towards sustainable products/services like green hotels [15] A development of the Theory of Reasoned Action, TPB was developed by [16]. This theory opines that human behavior is the outcome of three variables: Attitude (ATT), Subjective Norm (SNN), and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC). Collectively, all factors affect intention and further impact human behavior [1,16].

This study will focus on millennials as they are the drivers of the consumption economy. From the time the environmental movement began, their opinions and attitude have not been considered. Limited research has been carried out in India to understand the intentional behavior of the younger generation [17,18]. The Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports [19] stated that 27.5% of the Indian population is comprised of youth in the age bracket of 15–29. Therefore, it is essential to comprehend their viewpoint on environmental behavior [20] Also, since they must spend more time on this planet compared to the previous generation, they are more concerned about saving the environment and practicing protective measures [18]. Further, the younger generation is the future driver of the service economy, and it is of prime importance that, as marketers and industrialists, we pay attention to understand their behavior, which is governed by their intentions [20]. Hence, millennials were selected for conducting this study.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

The Theory of Planned Behavior framework comprises three variables: a person’s attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. These three variables collectively lead to forming an intention toward behavior that ultimately influences the behavior [16]. A person’s attitude determines whether they will reinforce a certain action positively or negatively [21]. The higher the degree of positive reinforcement for a particular behavior, the higher the probability of performing that behavior. The authors of [22] claimed that customers’ attitudes toward the environment are influenced by sustainable practices adopted by the green hotel. Available literature substantiates that a customer’s environmentally friendly attitude influences his intention to visit a green hotel [15]. The second variable of the TBP framework is the subjective norm. An individual values other people’s perspectives who are important to them and can be influenced by them in making decisions [1]. Available literature confirms that subject norms significantly influence customer’s attitude toward green hotels and behavioral intention [15,18] The last construct in the TPB model is perceived behavioral control, which is called “the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior” [23]. PBC assesses a person’s view of how effectively he/she can manage variables that can permit the behaviors required to face a particular situation [1]. Available literature confirms that an individual behavioral intention is, to a great extent, impacted by PBC to act in a desired way [24].

Intention is one of the significant factors that influences individual behavior. Intention refers to the possibility that a person will perform a particular behavior [25]. Similarly, green purchase intention is a customer’s commitment to taking part in an environmentally friendly activity [26], in this case to visit a green hotel. As discussed earlier, intention is the best antecedent of behavior [27]. It has also been discovered that intention acts as a mediator between behavior and attitude, social norm, and PBC [28]. It is crucial to understand the purchase intention of millennials. Since the last decade, millennials have received a substantial amount of attention from researchers, academicians, and marketers [29]. Millennials are individuals born between 1981 and 1997 [30]. Available literature highlights the relationship between year of birth and consumption pattern [31]. Research conducted by [32,33] explains that an economic condition faced by an individual in the past may have a long-lasting impact on his investment decisions and understanding of inflation. This explains why millennials spend differently compared to the previous generation.

Available literature shows that TPB has proved to be extremely useful in understanding pro-environmental behavior among the younger generation [18]. According to one report, 63% of young Indians traveled four times in the first six months of 2016. Despite this, in India, research on consumer purchasing intentions and behavior in environmentally friendly hotels is still in its infancy [1]. This study will explore the factors that drive millennial intention towards visiting green hotels by applying TPB. The findings of several researchers confirm the TPB’s relevance in measuring the intention of millennials to visit green hotels [1,17]. The following hypotheses (Figure 1) can be advanced in light of the debate above:

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. ATT = Attitude; SNN = Subjective Norm; PBC = Perceived Behavioral Control; GPI = Green Purchase Intention.

H1.

Millennials’ attitude to visit green hotels significantly influences their green purchase intention.

H2.

Subjective norm significantly influences millennials’ attitude(H2a) and PBC(H2b) to visit green hotel.

H3.

PBC significantly influences millennials’ green purchase intention.

H4.

Subjective norm significantly influences millennials’ green purchase intention to visit green hotel.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures and Questionnaire Development

This study followed a quantitative approach, and a self-administered questionnaire was used for the data collection, which was carried out online. The evaluation of the measurement model and the hypothesis was examined with the partial least square-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method. The survey utilized for the investigation adopted questions that are validated from previous studies [15,18,34]. The questionnaire is divided into four sections, comprising Attitude, Subjective Norm, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Green Purchase intention. Industry and academic experts examined the content validity of the questionnaire. Respondents had the questionnaire explained to them over the phone and it was sent through email for data collection. The questionnaire comprised 16 items: Attitude-7 items, Subjective Norm-3 items, PBC-3 items, and GPI-3 items. The Questionnaire used a seven-point Likert scale (“strongly disagree (1)–strongly agree (7)”) for measurement. Questionnaire items have been displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Research Instrument.

3.2. Data Collection

Preliminary data collection was conducted for one month from the younger population across the major Indian cities of Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, and Mumbai since these four cities feature the majority of green hotels. According to a report by the Green Building Council of India, Maharashtra is leading with the maximum number of green buildings, followed by Karnataka, Haryana, and Tamil Nadu [35]. For this particular reason, the above-mentioned cities were selected for preliminary data collection. In this study, purposive non-probability sampling was employed, and the survey was distributed online. Since the population is extremely large because every potential traveler represents the population, for conducting this preliminary study, a sample size of 30 respondents was selected. Afterward, adequate sample size data collection will be conducted. This is one of the limitations of this study. The result cannot be generalized for the entire population. Therefore, after completing this study and based on the results, an adequate sample size will be selected for the final study. Non-probability-based purposive sampling is performed for the section of the chosen population. Since the population is selected based on the judgment of the researcher, purposive non-probability sampling is used for this study. The demographic details of the respondents have been presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic details of the respondents.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

For conducting statistical analysis in this paper, structural equation modeling with the partial least square method was used. The instrument used to create the structural model was SmartPLS V3.0. SEM is a technique that is used to analyze the relationships between multiple variables in a complex system. The SEM approach combines two statistical methods to estimate partial model structures: principal component analysis (PCA) and ordinary least square regression (OLS). By combining PCA with OLS regression, the SEM method can estimate the partial model structures in the path model more accurately and efficiently than using either technique alone. Considering the features of the study’s sample, the PLS-SEM approach was considered appropriate. The analysis is conducted in two stages: first, measurement model evaluation to evaluate the research instrument’s validity and reliability, and second structural model evaluation to test the hypothesis.

3.4. Measurement Model Analysis

To measure the reliability and validity of the research instrument, the convergent and discriminant validity of the questionnaire needs to be verified. According to [36], if the outer loadings of each construct are larger than 0.70 and the average extracted variance (AVE) is greater than 0.50, convergent validity is established. The constructs’ AVE values are in the range of 0.728 to 0.745 and the outer loadings of the items were in the range of 0.741 to 0.950 (Table 3). Hence, model convergent validity was established. For the measurement of reliability, two measures were executed: Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability (CR). The study’s latent variable’s reliability statistics were greater than 0.70, which is the recommended value for establishing the reliability of the research instrument (Table 3).

Table 3.

Measurement model analysis.

According to [37], evaluation of discriminant validity is the most important step for a researcher as it confirms that latent variables, which are used to measure the causal relationships in the study, are, in a true sense, distinct from each other. One of the most widely used methods for measuring discriminant validity is the Fornell–Larcker criterion. However, ref. [37] suggested a new method, the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations methods. The results confirmed that discriminant validity is established using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, as the highest latent correlation value is 0.859 (Table 4). The HTMT ratio of all the constructs should be below 0.90 [37] to confirm discriminant validity. The result displayed in Table 5 confirms discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity (Fornell-Larcker criterion).

Table 5.

Discriminant Validity (HTMT ratio).

3.5. Structural Model Analysis

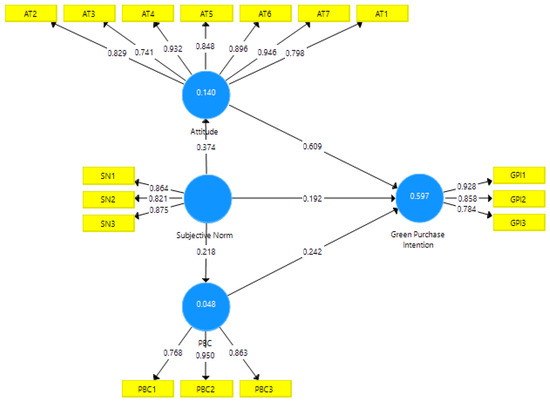

An examination of the structural model was performed after the measurement model analysis to verify the relationships that had been postulated. The proposed conceptual framework has four constructs and a total of five postulated relationships must be verified. The R2 value for AT was 0.140 and GPI was 0.597, exhibiting appropriate levels of predictive accuracy. Figure 2 contains the SEM results with the standardized regression weights. Additionally, Table 6 represents detailed hypothesis testing results. The result supported two out of the five hypotheses.

Figure 2.

Structural equation modelling results. AT = Attitude; SN = Subjective Norm; PBC = Perceived Behavioral Control; GPI = Green Purchase Intention.

Table 6.

Hypothesis Testing.

Of the variables impacting consumers’ Green Purchase Intention, AT (β = 0.609, p < 0.001) had a major impact on GPI. Thus, hypothesis H1 was supported. Also, SN (β = 0.374, p < 0.001) had a positive influence on AT. Thus, hypothesis H2a was supported. However, hypotheses H2b, H3, and H4, which proposed the effect of SN (β = 0.218, p > 0.1), PBC (β = 0.242, p > 0.1), and SN (β = 0.192, p > 0.1), respectively, were not supported.

4. Discussion

This study proposed to measure the intention of Indian millennials to visit green hotels. Evidence obtained from the results highlights that attitude has a positive and significant impact on millennials’ green purchase intention. Also, the subjective norm has a significant influence on the attitude of Indian millennials about the visit of green hotels. Our findings agree with the findings of [1], which confirmed the influence of attitude on young consumers’ green purchase intention to visit green hotels. However, the results were found to disagree with [1], which reported that PBC and subjective norms have a significant influence on young consumers’ green purchase intention to visit green hotels. A possible reason for this disparity could be the demographic differences between the two studies. In our study, 48% of the respondents are in the age bracket of 36–40. However, for [1], 58% of respondents were in the age bracket 18–25. Strong environmental concern among the younger generation in India is evident and they are aware of the health and environmental safety of green products [38].

The results show that attitude is the major factor that influences Indian millennials’ green purchase intention to visit green hotels. Our findings agree with several other studies that indicate millennials are concerned about the environment and ready to take sustainable measures to protect natural resources and surroundings [1,18,21].

4.1. Theoretical Implication

This paper provides empirical evidence for the usability of the Theory of Planned Behavior to predict millennials’ intention to visit green hotels in India. By revealing the importance of attitude and subjective norm, this study reconfirms the applicability of TPB for predicting millennials’ intention to visit green hotels. This study highlights that millennials are more concerned about protecting the environment than the previous generation. It outlines that millennials’ environmental concerns can be a driving force for the decision-making process, particularly concerning visits to green hotels. The findings also draw attention to the fact role of subjective norm in influencing millennials’ attitude toward green hotels. As results revealed, the subjective norm has a positive influence on the attitude of millennials, and attitude has a positive impact on green purchase intention to visit green hotels. The opinions of significant social members like family and friends have a favorable impact on the attitude.

4.2. Practical Implication

Hoteliers may find the study’s findings useful to market sustainable practices to attract millennials to visit green hotels. As highlighted in the paper, millennials are more concerned with protecting the environment, and hoteliers can design their marketing strategies accordingly. Environmental activists and influencers who are passionate about sustainable practices, particularly for travel and tourism, can be approached to create awareness among consumers to visit green hotels. This study also brings attention to the need to create awareness among consumers/millennials regarding green hotels, the various sustainable practices being implemented at such hotels, and the derived benefits to the consumers. A clear understanding of the benefits needs to be communicated through designed marketing efforts. It also suggests that policymakers create policies that promote the usage of green hotels and incentives should be granted to individuals who are taking part in this initiative. The government can provide subsidies for hotel establishments to build sustainable hotels. More and more encouragement should be made in collaboration with certification agencies like GBCI (Green Building Council of India) which certifies hotels as LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design). These kinds of certifications bring assurance of trust and quality to the users. With dedicated efforts, aligned marketing strategies, and a clear understanding of the usage benefits, millennials can be targeted and motivated to use maximum green hotels, which will promote sustainable tourism in the future.

5. Limitations and Future Scope

A few limitations were present in the study. First, this study focused only on millennials limited to specific regions and demographics. Opting for a larger sample size and including a diverse population could increase the generalizability of the study. Second, this study used a cross-sectional survey design in the preliminary analysis, which may limit the ability to establish causality between the variables. Hence, a longitudinal study is suggested for better results. Third, while the paper used the Theory of Planned Behavior as its theoretical framework, other psychological constructs, like awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, personal norm, and willingness to pay a premium, might have a big impact on millennials’ intention to stay in green hotels. Hence, further empirical investigation including the above-listed variables need to be conducted in the future for better results. Also, considering specific factors/services in green hotels that impact millennials’ intention to visit green hotels need to be considered. By addressing the above limitations and investigating the future scope, an in-depth knowledge of millennials’ intention to stay at eco-friendly hotels in India can be executed to enrich the contribution of this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J. and S.K.V.; methodology, S.J. and A.O.M.; software, S.J.; validation, S.J. and A.O.M.; formal analysis, S.J., S.K.V. and A.O.M.; investigation, S.J.; resources, S.J.; data curation, S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.; writing—review and editing, S.J. and A.O.M.; supervision, S.K.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used are made available in the present work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An application of the theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers’ green hotel visit intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’souza, C.; Taghian, M. Green advertising effects on attitude and choice of advertising themes. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2005, 17, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Matharu, M.; Lim, W.M.; Ali, F.; Kumar, S. Consumer adoption of green hotels: Understanding the role of value, innovation, and involvement. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 819–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F.; Milego, R.; Fons, J.; Schröder, C.; Giulietti, S.; Stanik, R. Report on Feasibility for Regular Assessment of Environmental Impacts and Sustainable Tourism in Europe; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, T.; Dolnicar, S.; Leisch, F. The sustainability–profitability trade-off in tourism: Can it be overcome? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qubbaj, A.I.; Peiró-Signes, A.; Najjar, M. The Effect of Green Certificates on the Purchasing Decisions of Online Customers in Green Hotels: A Case Study from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2013, 15, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Lee, M.; Gunarathne, N. Do green awards and certifications matter? Consumers’ perceptions, green behavioral intentions, and economic implications for the hotel industry: A Sri Lankan perspective. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampora, A.; Preziosi, M.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Merli, R. The Role of Hotel Environmental Communication and Guests’ Environmental Concern in Determining Guests’ Behavioral Intentions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. The influence of values and attitudes on green consumer behavior: A conceptual model of green hotel patronage. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 20, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Wu, H. Tourists’ perceptions of green building design and their intention of staying in green hotel. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Y.; Awang, Z.; Jusoff, K.; Ibrahim, Y. The influence of green practices by non-green hotels on customer satisfaction and loyalty in hotel and tourism industry. Int. J. Green Econ. 2017, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; Lau, L.B.Y. Explaining green purchasing behavior: A cross-cultural study on American and Chinese consumers. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2002, 14, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green products: An exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, M.S.S.; Nascimento, P.O.; Freire, A.P. Reporting Behaviour of People with Disabilities in relation to the Lack of Accessibility on Government Websites: Analysis in the light of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2022, 33, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray-Lake, L.; Flanagan, C.A.; Osgood, D.W. Examining trends in adolescent environmental attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors across three decades. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Youth Policy. Youth Policy 2014. 18 December 2014. Available online: https://www.rgniyd.gov.in/sites/default/files/pdfs/scheme/nyp_2014.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behaviour towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.W.; Al-Gahtani, S.S.; Hubona, G.S. The effects of gender and age on new technology implementation in a developing country: Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Inf. Technol. People 2007, 20, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheraz, N.; Saleem, S. The Consumer’s pro environmental attitude and its impact on green purchase behavior. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, R.; Agag, G.; Shehawy, Y.M. Understanding guests’ intention to visit green hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 494–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F. Antecedents of the green behavioral intentions of hotel guests: A developing country perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.F.; Najib, M.; Sumarwan, U.; Asnawi, Y.H. Rational and moral considerations in organic coffee purchase intention: Evidence from Indonesia. Economies 2022, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, C.J.; Li, G.; Vine, D.J. Are millennials different? In Handbook of US Consumer Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 193–232. [Google Scholar]

- Dimock, M. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin. Pew Res. Cent. 2018, 1, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Desilver, D. The Politics of American Generations: How Age Affects Attitudes and Voting Behavior. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/07/09/the-politics-of-american-generations-how-age-affects-attitudes-and-voting-behavior/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Malmendier, U.; Nagel, S. Learning from inflation experiences. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, U.; Nagel, S. Depression babies: Do macroeconomic experiences affect risk taking? Q. J. Econ. 2011, 126, 373–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Chai, H. Consumers’ intentions towards green hotels in China: An empirical study based on extended norm activation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trierweiler, S. Annual Top 10 States for LEED in India announced by GBCI India. Green Building Council of India. 2021. Available online: https://www.gbci.org/annual-top-10-states-leed-india-announced-gbci-india (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Mohmad Sidek, M.H. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varah, F.; Mahongnao, M.; Pani, B.; Khamrang, S. Exploring young consumers’ intention toward green products: Applying an extended theory of planned behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 9181–9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).