Methods and Scenario Analysis into Regional Area Participatory Planning of Sustainable Development: The “Roses Valley” in Southern Morocco, A Case Study †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method and Scenario Analysis into Regional Area: The Territorial Approach

- -

- physical resources, in particular natural resources, facilities and infrastructure, and historical, architectural, urban and landscape heritage, as well as and their management;

- -

- human resources (residents in the area, such as people who move there and people who leave it, i.e., demographic characteristics and the social structure of the population);

- -

- activities (enterprises and the related industry sector, their weight within the sector, size, geographical concentration, etc.) and employment;

- -

- know-how and skills in the area, culture and identity (the values generally shared by the players in the territory, their interests, attitudes, forms of recognition, customs, etc.);

- -

- the level of “governance” (local institutions and administrations, rules, collective operators, relationships between these stakeholders, the degree of autonomy in managing development, including financial resources and forms of consultation and participation, etc.);

- -

- the area’s image and perception (both among the inhabitants themselves and externally), communication within the area and relationships with the outside world (in particular, the area’s positioning in the various markets, contacts with other areas, exchange networks, etc.).

3. The Case Study: “The Roses Valley”

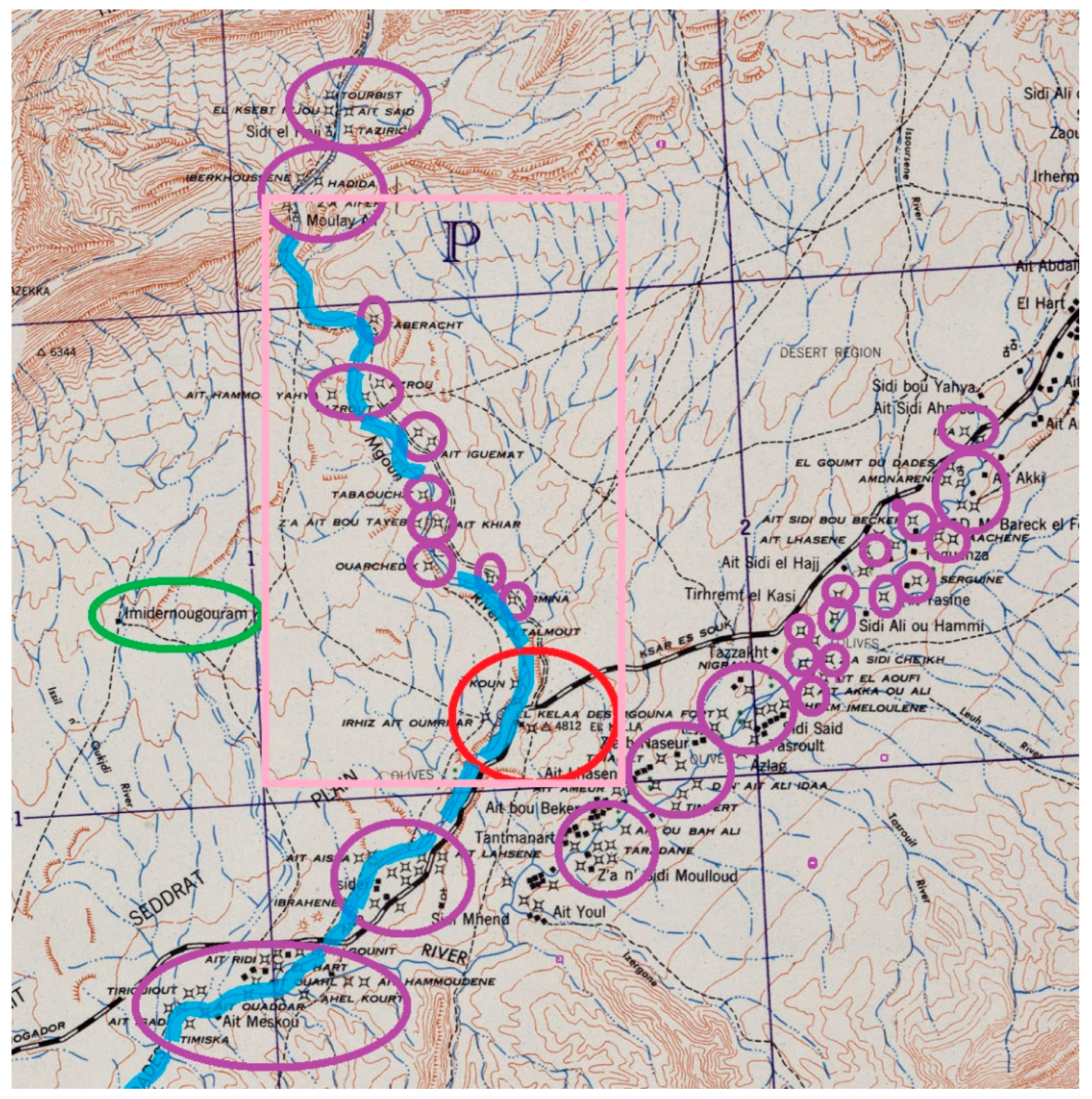

3.1. The Ribbon Oases

3.2. The Kelaat M’Gouna Urban Area

3.3. The Roses Garden of Kelaat M’Gouna

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | The Biosphere Reserve ‘Oasis du Sud Marocain was designated in 2000. It has rich agronomic diversity, including vast areas with date palms, acacia forests and other high-altitude forests covered with Juniperus thurifera, J. phoenicea and Quercus rotundiforia, among other species. In particular, the area is home to dorcas gazelles, gazelles de cuvier (Gazella cuvieri), barbarian sheep (Ammotragus lervia), ubara otards (Chlamydotis undelata) and cobras (Naja haje). The population of the Oasis du Sud Marocain has lived in this area for thousands of years. Most of their economic activities come from agriculture, particularly the production of cereals, potatoes, olives and, above all, dates, which are the backbone of the local economy. Recently, the cultivation and processing of new products, such as apples, roses and henna, significantly increased the farmers’ incomes. |

| 2. | Project “Moroccan migration to Italy in time of global economic crisis” in partnership with Moulay Ismail University, Department of Sociology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Meknes, Morocco on the basis of the Bilateral Agreement for Scientific and Technological Cooperation CNR-Italy/CNRST-Morocco 2012–2013. |

| 3. | https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/arab-states/oasis-sud-marocain (accessed on 16 March 2023). |

| 4. | The region is classified by UNESCO as being part of the Biosphere Reserve of the Southern Moroccan Oases ReBOSuM. The ecological, environmental and socio-economic importance of the region faces several challenges, as anthropogenic impacts on the oasis ecosystem are changing the trajectory of ecosystem services. |

| 5. | Bayoud disease is an epiphytic fungal disease of date palms. The disease was first reported in Morocco in 1870. The term ‘bayoud’ is derived from the Arabic abiadh (‘white’) and refers to the whitish colouring of diseased fronds. |

| 6. | Timbuctu (Tumbuktu), originating as a cultural centre, became a trading centre in the 15th century. Caravan routes connected it to Sudan, Egypt, Tunis and Morocco. It cultivated trade relations with Italy and, in particular, with Florence. |

| 7. | https://www.hcp.ma/Developpement-regional_r614.html (accessed on 28 March 2023). |

References

- Royaume du Maroc, Haut-Commissariat au Plan, Direction Régionale de Draa Tafilalet. Monographie Régionale 2021, La région Draa Tafilalet. Available online: https://www.hcp.ma/draa-tafilalet/docs/monographies/Monographie%20Regionale%20de%20l%27%27annee%202021.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Salem, A.B. Changements Climatiques Dans les Oasis de Tafilalet Sud Est du Maroc; Editions Universitaires Européennes: Sarrebruck, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuisma, J.; Haanpera, H. Water quality pressures and water management. In Encounters across the Atlas: Fieldtrip in Morocco 2011; Minoia, P., Kaakinen, I., Eds.; Unigrafia: Helsinki, Finland, 2012; pp. 58–71. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/37939 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Bertini, A.; Caruso, I.; Cuturi, C.; Vitolo, T. Preserving and valorising the settlement system of South Morocco. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, Granada, Spain, 12–15 June 2018; pp. 1895–1906. [Google Scholar]

- Bertini, A. Sviluppo sostenibile nel Sud del Marocco. In Percorsi Migranti; Bruno, G.C., Caruso, I., Sanna, M., Vellecco, I., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Milano, Italy, 2011; pp. 143–160. ISBN 978-88-386-7296-5. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, I.; Vitolo, T.; Bertini, A. Cultural heritage and territorial development: A comparative analysis between Italy and Morocco. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, Granada, Spain, 12–15 June 2018; pp. 719–730. [Google Scholar]

- Troin, J.F.; Berriane, M.; Guitouni, A.; Laouina, A.; Kaioua, A. Maroc: Régions, Pays, Territoires; Maisonneuve et Larose: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R. Territorial capital and regional development. In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories; Capello, R., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lacquement, G.; Chevalier, P. Capital territorial et développement des territoires locaux, enjeux théoriques et méthodologiques de la transposition d’un concept de l’économie territoriale à l’analyse géographique. Ann. De Géographie 2016, 5, 490–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berriane, M. Dynamiques Territoriales et Politiques Publiques: Territoires Fonctionnels et Territoires Officiels In Le Maroc au Présent: D’une Époque à L’Autre, une Société en Mutation; Dupret, B., Rhani, Z., Boutaleb, A., Ferrié, J.-N., Eds.; Centre Jacques-Berque: Casablanca, Morocco, 2015; Available online: http://books.openedition.org/cjb/998 (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Michon, G.; Berriane, M.; Aderghal, M.; Landel, P.-A.; Medina, L.; Stephane, G. Construction d’une destination touristique d’arrière-pays: La « Vallée des roses » (Maroc). GÉOgraphie Et DÉVeloppement Au Maroc. 2018, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sadki, A. Environnement, paysage et projet de territoire. Vers une approche territoriale pour la sauvegarde et la mise en valeur de la réserve de biosphère des oasis du sud marocain. Master’s Thesis, Université Senghor, Alexandrie, Egypt, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanouar, B.; Kradi, C. Actes du Symposium International Sur: Le developpement Durable des Systemes Oasiens; Institut National de la Recherche Agronomiqu: Erfoud, Morocco, 2005; Available online: https://www.inra.org.ma/sites/default/files/publications/ouvrages/oasis.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Office Régionaux de la Mise en Valeur dé l’Agricol, OMRVA 2019. Available online: https://www.ormvatafilalet.ma/ (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Hammer, J. La biblioteca segreta di Timbuctù. In La Vera Storia Degli Uomini Che Salvarono Trecentomila Libri Dalla Furia Della Jihad; Rizzoli: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sadki, A. Urbanisme et Dégradation de L’Habitat Traditionnel des Oasis du Sud-Est Marocain: L’Exemple des Ksour du Tafilalet (Province d’Errachidia). Available online: http://www.archi-mag.com/essai_18.php (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Sadiki, M.; Essami, A.; Bouaouinate, A. Les ksour du Tafilalet: Un patrimoine culturel et touristique en déclin. J. Political. Orbits 2019, 3, 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Boussalh, M.; Cancino, C.; Marcus, B.; Wong, L. The development of a conservation and rehabilitation plan (CRP) for the earthen Kasbah of Taourirt in southern Morocco. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016, 7, 3579–3583. [Google Scholar]

- Ginex, G. Un sistema interattivo per la conoscenza e la gestione del patrimonio culturale in area mediterranea. La Kasbah di Ait Ben Haddou, un progetto di rappresentazione, (Cultural heritage Documentation. The Kasbah of Ait Ben Haddou in Morocco). Disegnare Con 2010, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagermeier, A.; Amzil, L.; Elfasskoui, B. Touristification of the Moroccan Oasis Landscape: New Dimensions, New Approaches, New Stakeholders and New Consumer Formulas. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/37245318/Touristification_of_the_Moroccan_oasis_landscape_new_dimensions_new_approaches_new_stakeholders_and_new_consumer_formulas (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Cancino, C.; Marcus, B.; Boussalh, M. Conservation and Rehabititation Plan for Tighermt (Kasbah) Taourirt, Southern Morocco; The getty Conservation Institues, Los Angees, Centre de Conservation et de rehabilitation du Patrimoine Architectural atlasique et subatlasique (CERKAS): Ouarzazate, Morocco, 2016; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- World Heritage Earthen Architecture Programme (WHEAP). Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/earthen-architecture (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Bertini, A.; Caruso, I.; Vitolo, T. Inland Areas, Protected Natural Areas and Sustainable Development. Eng. Proc. 2022, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, R. Lightfoot, Moroccan Khettara: Traditional Irrigation and Progressive Desiccation. Geoforum 1996, 27, 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.B. Futures under glass: A recipe for people who hate to predict. Futures 1990, 22, 820–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Map Surface ha | Core Area(s) ha | Buffer Zone(s) ha | Transition Zone(s) ha |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7,185,371 | 908,581 | 4,619,230 | 1,657,560 |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Biosphere Reserve Raw earth constructions, i.e., kasbah, igherem and entire neighbourhoods (ksars) Local handicrafts Tourist equipment Rural tourism Rose picking Rose processing Rose processing techniques Identity and typical landscape in the area Climatic conditions suitable for diversifying tourism Distance from the polluted urban environment Healthy environment Well-maintained oases Date production Wrought iron craftsmanship Identity-based production—mantice Identity-based production—rural ceramics Identity-based production—Weaving Identity-based production—shoemaking Identity-based production—daggers (typical of and exclusive to Kelaat M’Gouna) | Kettara in desiccation Peripherals Reduced agricultural production and date production Few economic activities Low employment rates in general, and high youth employment in particular Low attractiveness for residents Low attractiveness for tourists and travellers Most economic activities and, to a large extent, those related to the tourism industry are in the hands of external companies, which have little involvement in local communities Income from tourism activities contributes little to improving the living standards of local communities A lack of ecological education that can make people understand that the old way of life is better than the contemporary one Innovative and non-traditional techniques are problematic because they do not use natural products that stem from the production of rose by-products The world’s largest solar power plant located just 10 km from Ouarzazate, inaugurated in 2016, does not power the Draa Tafilalet region |

| Opportunities World Heritage Earthen Architecture Programme (WHEAP) [22] Federation Interprofessionelle Marocainede la Rose a Parfume New Development Model (NMD) New Action Plan for the tourism sector for the period 2023–2026 with an allocation of 6.1 billion Moroccan dinars (the tourism sector has a new action plan, with a new strategic roadmap for the period 2023–2026. More than DH 6.1 billion will be allocated to the implementation of this roadmap. For the implementation of this roadmap is scheduled to take 4 years. The plan aims to attract 17.5 million tourists in 2026, after reaching 11 million last year. The plan has multipe specific aims: (1) to reach USD 120 billion in foreign exchange earnings; and (2) to create 200,000 new direct and indirect jobs by 2026. To achieve these objectives, the sector will have to achieve the following aims: (a) creating a new diversified structure of the tourism offer; (b) strengthening air connections; (c) supporting and promoting e-marketing; (d) diversifying the cultural and free-time offers; (e) redeveloping the existing hotel heritage and creating new hotel facilities; (f) strengthening human capital via an attractive training framework (Joint Note No. 42-INAC-HCP—April 2023).) Développement Rural et des Eaux et Forêts à la zone d’action de ORMVA Tafilalet, 2020 | Threats Architectural and natural heritage under threat Desertification Drying out of khettara irrigation systems Palm disease (BAYARD) Migration processes of local populations Falsification in the production of rose derivatives Lack of brand protection for the processing and production chains of rose derivatives |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bertini, A.; Caruso, I.; Vitolo, T. Methods and Scenario Analysis into Regional Area Participatory Planning of Sustainable Development: The “Roses Valley” in Southern Morocco, A Case Study. Eng. Proc. 2023, 39, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023039008

Bertini A, Caruso I, Vitolo T. Methods and Scenario Analysis into Regional Area Participatory Planning of Sustainable Development: The “Roses Valley” in Southern Morocco, A Case Study. Engineering Proceedings. 2023; 39(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023039008

Chicago/Turabian StyleBertini, Antonio, Immacolata Caruso, and Tiziana Vitolo. 2023. "Methods and Scenario Analysis into Regional Area Participatory Planning of Sustainable Development: The “Roses Valley” in Southern Morocco, A Case Study" Engineering Proceedings 39, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023039008

APA StyleBertini, A., Caruso, I., & Vitolo, T. (2023). Methods and Scenario Analysis into Regional Area Participatory Planning of Sustainable Development: The “Roses Valley” in Southern Morocco, A Case Study. Engineering Proceedings, 39(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023039008