Study of Building Sense of Place in Network World †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sense of Place

2.2. Internet

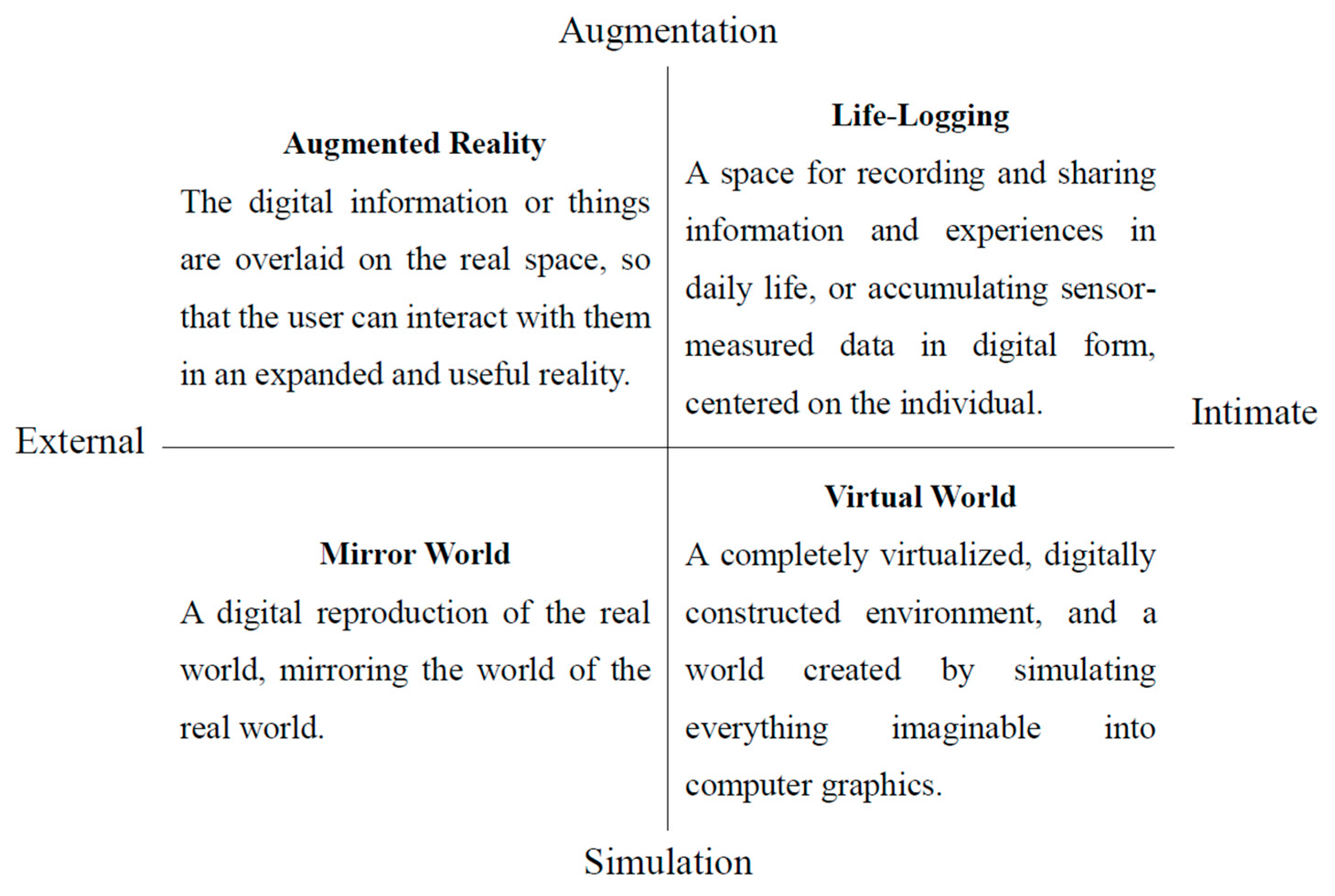

2.3. Cyberspace

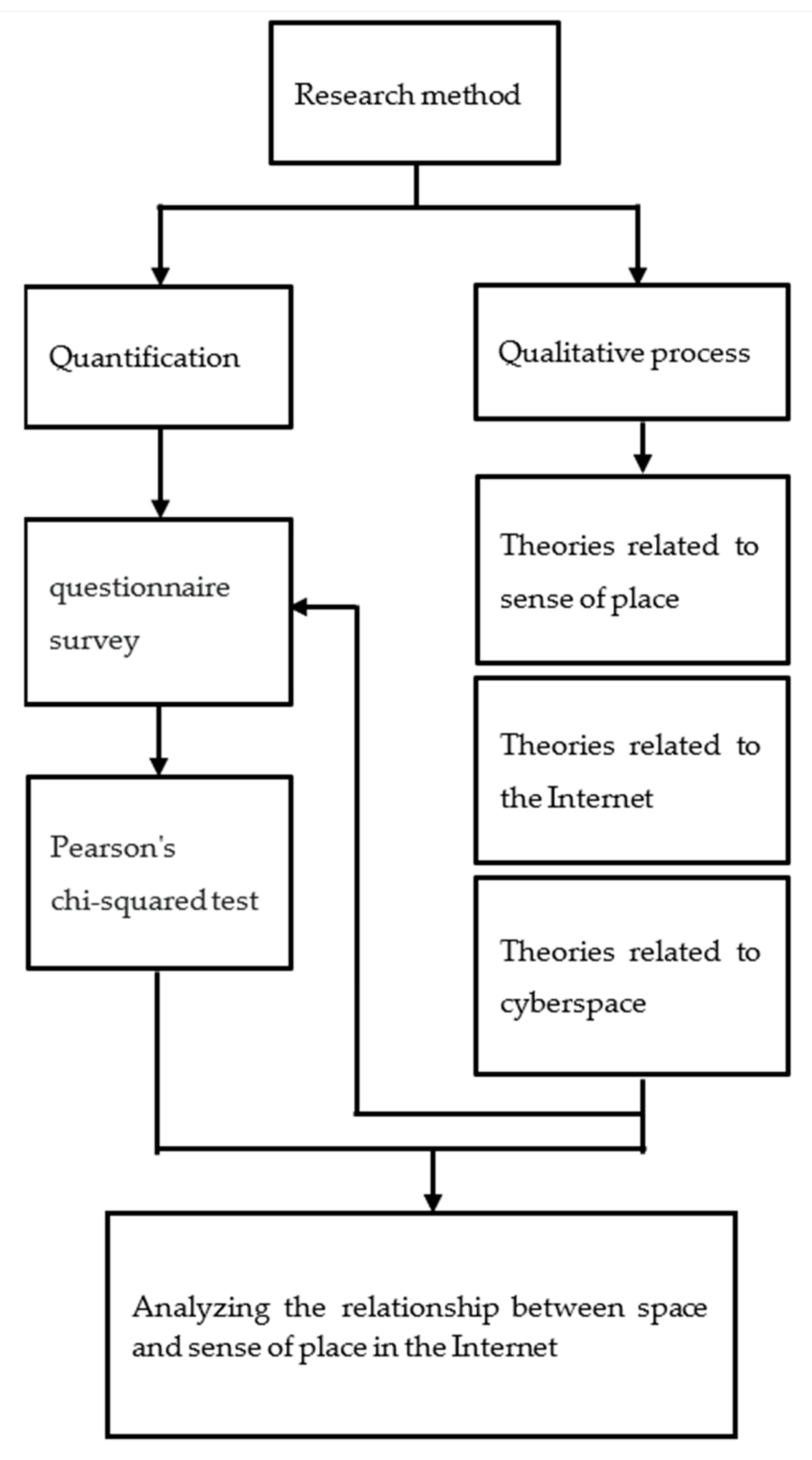

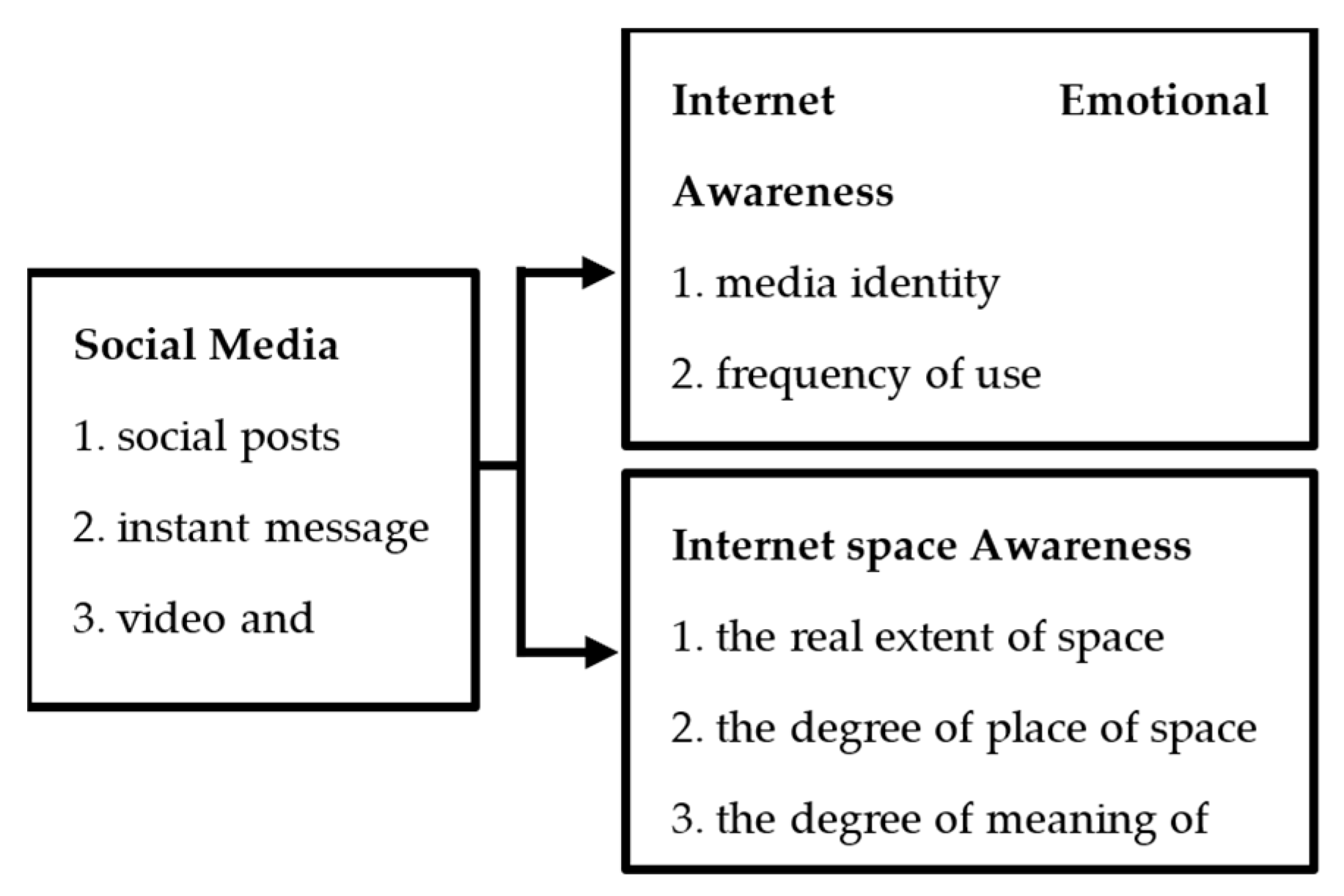

3. Research Method

4. Research Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Relph, E.C. Place and Placelessness; Pion Limited: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Power-Geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place. Mapping the Futures; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Bibliovault OAI Repository; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S.; Dourish, P. Re-Place-Ing Space: The Roles of Place and Space in Collaborative Systems. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Boston, MA, USA, 16–20 November 1996. [Google Scholar]

- National Development Council. Communications Market Development Overview and Trends Survey Analysis Commissioned Research Case, Broadband Usage Survey Summary Report; National Development Council: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018.

- National Development Council. 2018 Mobile Phone Users’ Digital Opportunity Survey (AE080006); Academia Sinica: Taipei, Taiwan, 2019.

- Tsai, W.C. Sense of Place: The Experience, Memory and Imagination of Environment Space; Liwen Publishing Group: Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. Serbiula 1975, 65, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L. For Better or Worse: Exploring Multiple Dimensions of Place Meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.; Stedman, R. Sense of Place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamai, S. Sense of Place: An Empirical Measurement. Geoforum 1991, 22, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, S.J. The Role and Impact of Virtual Community on Sustainable Rural Development; Review of Agricultural Extension. Science 1998, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.I. The Social Image of Internet Users vs. Non-Users. J. Libr. Inform. Sci. 2001, 27, 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, S.H. Web2.0 Interactive Space. Master’s Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, C.L.; Liang, B.K. Connections Between the Cyberspace and the Space of Places—A Case Study of Ford’s F.P.R. Club. Environ. Worlds 2009, 20, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.S. Publishing, Place and Cultural Imagination: Media Spaces and Cultural Landscape of “The Lord of the Rings” Thought and Words. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2010, 48, 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. The Conflict Between Copyright and Free Flow of Information and the Solutions: From Real World to Cyberspace. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.C. Development of Japanese “Metaverse” Industry and Policy Discussion. Econ. Outlook Bimon. 2022, 200, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.Y. Imagine the development of “metaverse”. Econ. Res. Mon. 2022, 45, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.W. Meta-Universe: Are You Ready for the Rise of Infinite Opportunities as Technology Giants Compete for Investment? Global Publishing Group: Taipei, Taiwan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Feeling | Sensory Methods | |

|---|---|---|

| Content | Effects | |

| Sense of space | 1. Subjective/objective 2. Real/abstract 3. Near/far | Providing stimulation |

| Sense of time | 1. Venue 2. Viewpoint 3. State | Providing stimulation |

| Five senses | 1. Sight 2. Hearing 3. Smell 4. Touch 5. Taste | Receiving stimuli |

| Awareness, Sensory memory | Memories are formed and feelings are accumulated | Giving meaning |

| Level | Sense of Place Level |

|---|---|

| Content | |

| 0 | Not having any sense of place |

| 1 | Knowledge of being located in a place |

| 2 | Belonging to a place |

| 3 | Attachment to a place |

| 4 | Identifying with the place goals |

| 5 | Involvement in a place |

| 6 | Sacrifice for a place |

| Item | Internet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Web 1.0 | Web 2.0 | Web 3.0 | |

| Period | 1990–2005 | 2005–2020 | 2020–now |

| Ownership | Company | Company–individual | Individual |

| Symbols | Static web page | Social media, wikipedia, blogs | Cryptocurrency, non-fungible token |

| Concept | Messaging and data transfer | Real-time interactive communication | Decentralization |

| Relationship with people | Internet–people | People–internet–people | |

| Relationship with world | Dependence | Dependence–parallel | |

| Web Version | Viewpoint | |

|---|---|---|

| Author | Relevant Research Contents | |

| 1.0 | S-J Tung (1998) [12] |

|

| C-I Wu (2001) [13] |

| |

| 2.0 | S-H Weng (2009) [14] |

|

| C-L Tu; B-K Liang (2009) [15] |

| |

| C-S Sun (2010) [16] |

| |

| Jeffrey Li (2010) [17] |

| |

| 2.0 | 3.0 | W-C Hong (2022) [18] |

|

| S-Y Peng (2022) [19] |

| |

| Terminology | Questionnaire Design | |

|---|---|---|

| Corresponding Sense of Place Theory | Likert Scale | |

| Media identity | Place identity | (low) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 (high) |

| Media dependence | Place dependence | (low) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 (high) |

| Frequency of use | Time | (low) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 (high) |

| Sense of event reality | Experience | (real) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 (virtual) |

| The real extent of space | Space | (real) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 (virtual) |

| The degree of meaning of space | Place | (space) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 (place) |

| Importance | Meaning | (low) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 (high) |

| Ranking | Social Media | Number of Appearances |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dcard | 4 |

| 2 | Facebook Meta | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | |

| 4 | Line | 3 |

| 5 | Messenger | 3 |

| 6 | TikTok | 3 |

| 7 | 3 | |

| 8 | YouTube | 3 |

| 9 | Zenly | 3 |

| 10 | 2 | |

| 11 | 2 | |

| 12 | Xiaohongshu | 2 |

| Social Media | Media Identity | Frequency of Use | Media Dependence | Sense of Event Reality | Real Extent of Space | Degree of Meaning of Space |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s cardinality | 45.240 | 35.380 | 55.327 | 2.812 | 18.917 | 2.383 |

| Degrees of freedom | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Asymptotic significance (two-tailed test) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.590 | 0.001 | 0.666 |

| Media Identity | Social Posts | Instant Message | Video and Audio Information | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | |

| Low | 357 | 356.7 | 0.30 | 311 | 285.3 | 25.70 | 188 | 214 | −26.00 |

| Intermediate | 671 | 614.6 | 56.40 | 468 | 491.7 | −23.70 | 336 | 368.8 | −32.80 |

| High | 815 | 804.2 | 10.80 | 599 | 643.3 | −44.30 | 516 | 482.5 | 33.50 |

| Significance | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.008 | ||||||

| Frequency of Use | Social Posts | Instant Message | Video and Audio Information | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | |

| Low | 402 | 367.9 | 34.10 | 298 | 294.3 | 3.70 | 183 | 220.8 | −37.80 |

| Intermediate | 523 | 486.7 | 36.30 | 361 | 389.3 | −28.30 | 284 | 292 | −8.00 |

| High | 795 | 795.8 | −0.80 | 616 | 636.7 | −20.70 | 499 | 477.5 | 21.50 |

| Significance | 0.001 | 0.035 | 0.020 | ||||||

| Media Dependence | Social Posts | Instant Message | Video and Audio Information | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | |

| Low | 419 | 371.7 | 47.30 | 293 | 297.3 | −4.30 | 180 | 223 | −43.00 |

| Intermediate | 599 | 527.1 | 71.90 | 378 | 421.7 | −43.70 | 288 | 316.3 | −28.30 |

| High | 586 | 658.8 | −72.80 | 542 | 527 | 15.00 | 453 | 395.3 | 57.70 |

| Significance | 0.000 | 0.056 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Real Extent of Space | Social Posts | Instant Message | Video and Audio Information | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | |

| Close to the real space | 511 | 528.3 | −17.30 | 451 | 396.4 | 54.60 | 268 | 305.4 | −37.40 |

| In between | 590 | 581.1 | 8.90 | 401 | 436 | −35.00 | 362 | 335.9 | 26.10 |

| Close to virtual space | 641 | 632.6 | 8.40 | 455 | 474.7 | −19.70 | 377 | 365.7 | 11.30 |

| Significance | 0.666 | 0.004 | 0.031 | ||||||

| Importance | Interactivity | Anonymity | Privacy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | |

| Low | 41 | 57.6 | −16.60 | 87 | 57.6 | 29.40 | 57 | 57.6 | −0.60 |

| Intermediate | 129 | 143.7 | −14.70 | 171 | 143.7 | 27.30 | 140 | 143.7 | −3.70 |

| High | 244 | 202.8 | 41.20 | 130 | 202.8 | −72.80 | 204 | 202.8 | 1.20 |

| Significance | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.861 | ||||||

| Importance | Dependency | Identity | Immersion | ||||||

| fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | |

| Low | 61 | 57.6 | 3.40 | 46 | 57.6 | −11.60 | 62 | 57.6 | 4.40 |

| Intermediate | 138 | 143.7 | −5.70 | 128 | 143.7 | −15.70 | 132 | 143.7 | −11.70 |

| High | 209 | 202.8 | 6.20 | 237 | 202.8 | 34.20 | 213 | 202.8 | 10.20 |

| Significance | 0.624 | 0.004 | 0.485 | ||||||

| Importance | Sense of Life | Amount of Information | Special Experiences | ||||||

| fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | fo | fe | fo-fe | |

| Low | 43 | 57.6 | −14.60 | 51 | 57.6 | −6.60 | 70 | 57.6 | 12.40 |

| Intermediate | 135 | 143.7 | −8.70 | 151 | 143.7 | 7.30 | 169 | 143.7 | 25.30 |

| High | 233 | 202.8 | 30.20 | 202 | 202.8 | −0.80 | 153 | 202.8 | −49.80 |

| Significance | 0.007 | 0.770 | 0.000 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, S.-J.; Li, S.-T. Study of Building Sense of Place in Network World. Eng. Proc. 2023, 38, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023038060

Feng S-J, Li S-T. Study of Building Sense of Place in Network World. Engineering Proceedings. 2023; 38(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023038060

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Shih-Jen, and Si-Ting Li. 2023. "Study of Building Sense of Place in Network World" Engineering Proceedings 38, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023038060

APA StyleFeng, S.-J., & Li, S.-T. (2023). Study of Building Sense of Place in Network World. Engineering Proceedings, 38(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023038060