1. Introduction

Climate change is a global issue and a top priority for both the European Union and Greece. In order to reduce the impact of climate change, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions must be minimized. Greece’s Ministry of Environment and Energy have a long-term goal to decrease total emissions to about 13 Mt CO

2eq until 2050 [

1]. According to recent data, in Greece, total GHG emissions were 70.6 Mt CO

2eq in 2023. More specifically, the power industry sector accounted for 20.68% of the total GHG emissions [

2]. In the same year, fossil fuels contributed 42.97% of the total energy mix with 10.13% from lignite and 32.84% from natural gas [

3]. It is also important to mention that by 2028 energy production from lignite would be discontinued. For the reasons outlined above, the increased use of renewable energy sources (RESs) is of utmost importance for electricity production. Due to stability issues and their intermittent nature, RES expansion is limited. To address this, RES growth should be accompanied by the installation of energy storage systems (ESSs).

One of the main challenges associated with RES is the mismatch in timing between renewable energy generation and energy demand. With regard to energy storage, the power system not only achieves greater stability and reliability but also enhances efficiency by saving potential wasted energy from RES. According to a study concerning the power system of Jeju Island, South Korea, covering the period from 2015 to 2019, with the addition of 50 MW battery energy storage system (BESS) to a power system with 580 MW installed RES capacity, it has been demonstrated that renewable energy curtailment was reduced by 15% [

4]. Over the years, a variety of energy storage technologies have been developed, including lithium-ion batteries, hydrogen-based storage and pumped hydro storage.

Chemical batteries are the leading technology for grid-scale energy storage applications, with efficiency levels reaching 95% [

5]. However, serious concerns have been raised regarding the environmental impacts at the end of their lifecycle [

6]. Regarding green hydrogen, excess energy from RES is utilized to generate hydrogen via water electrolysis and then the produced hydrogen is stored under appropriate pressure and temperature conditions. Subsequently, using a fuel cell, the hydrogen is converted back to electricity [

7]. Although it produces almost zero emissions, such a process is considerably less efficient than accumulating energy in a chemical battery. An additional energy storage technology is pumped hydro storage, in which surplus electricity is used to pump water into the hydropower reservoir, enabling the generation of electricity when needed, through hydroelectric power [

8]. Regarding Greece’s energy storage development, it is planned to have 1.5 GW of installed storage capacity by the end of 2030 mainly focused on pumped hydro storage according to International Energy Agency [

9].

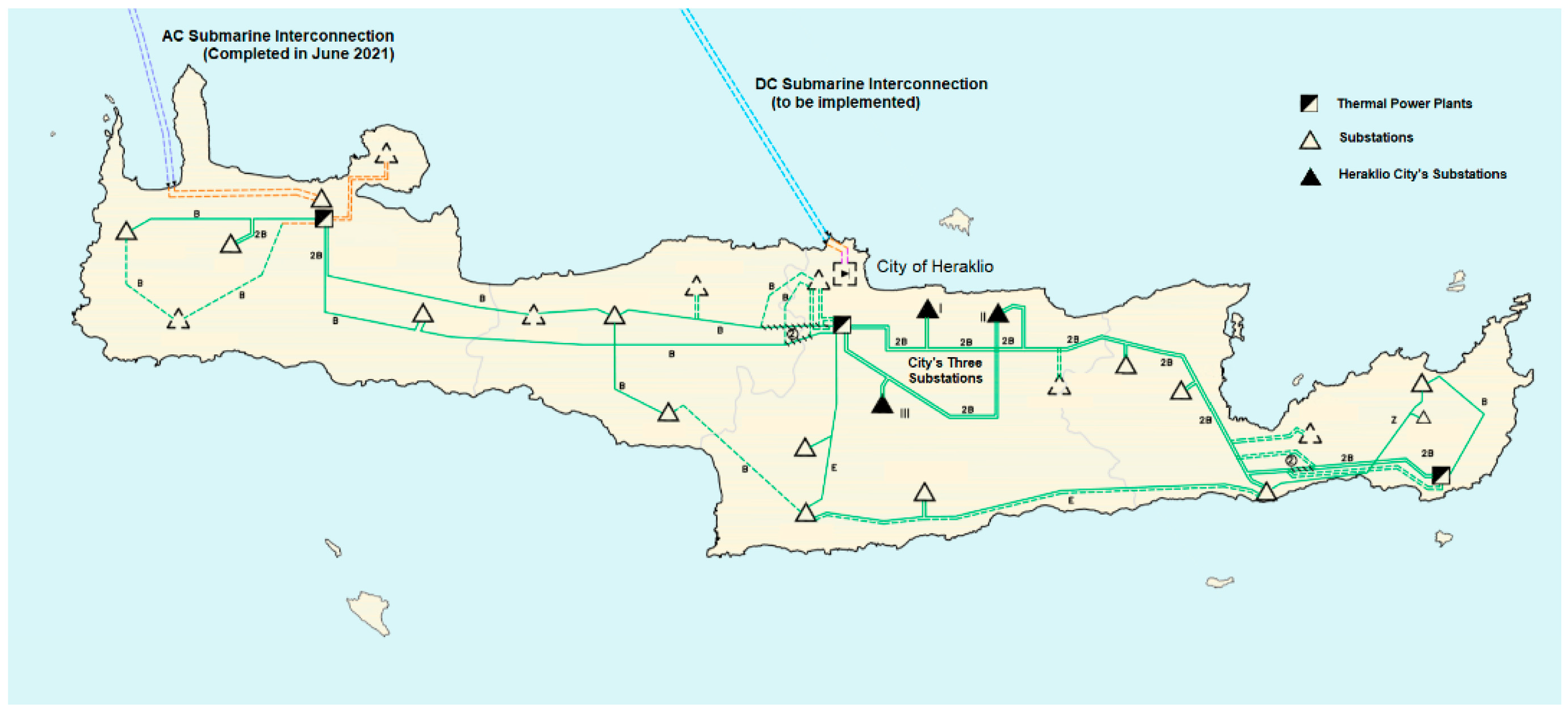

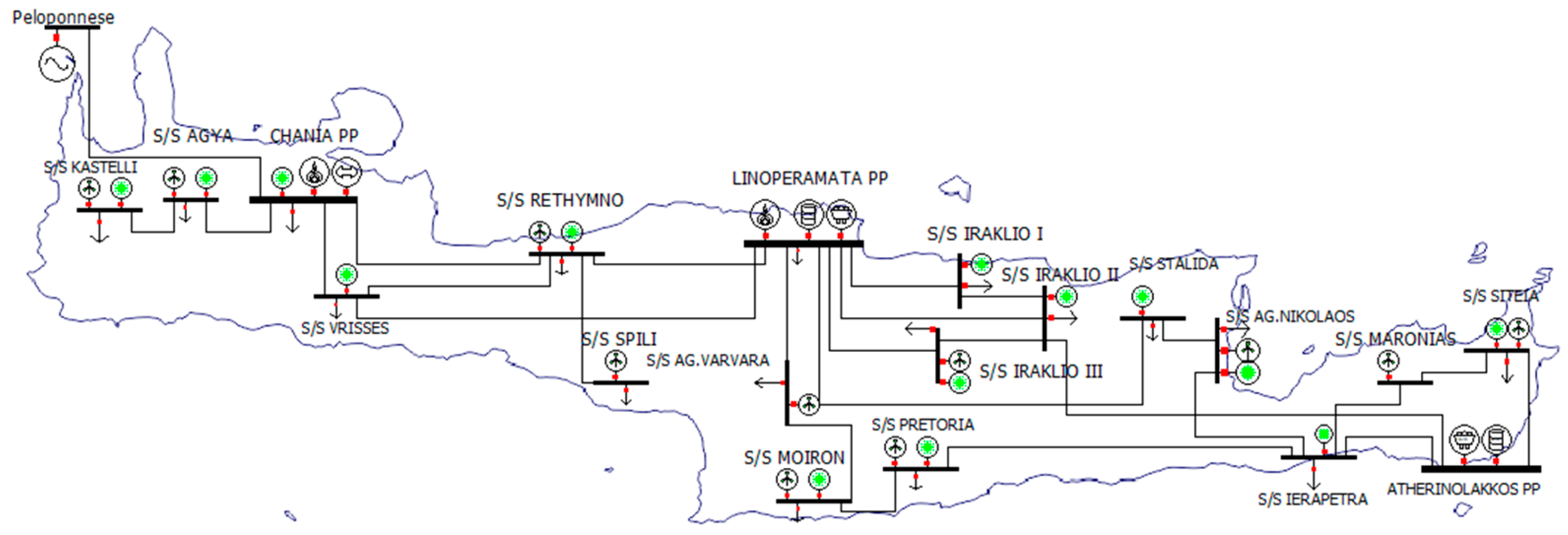

In this study, the island of Crete is examined due to its unique characteristics in the Greek power system. As a result of its location, Crete has significant wind and solar potential. However, despite these resources, RES deployment in Crete has still not reached its peak for reasons mentioned above. To address this, two interconnections with Greek mainland are being implemented. The first (small) interconnection connects Chania with the Peloponnese region; this interconnection is the deepest HVAC submarine line in the world and has a capacity of 2 × 200 MVA. The second (big) interconnection will connect Athens with Heraklion via an HVDC line with capacity of 2 × 500 MW. The small interconnection is currently being operated with a 150 MW limit, and the big interconnection is expected to be partially operated in the first months of 2026.

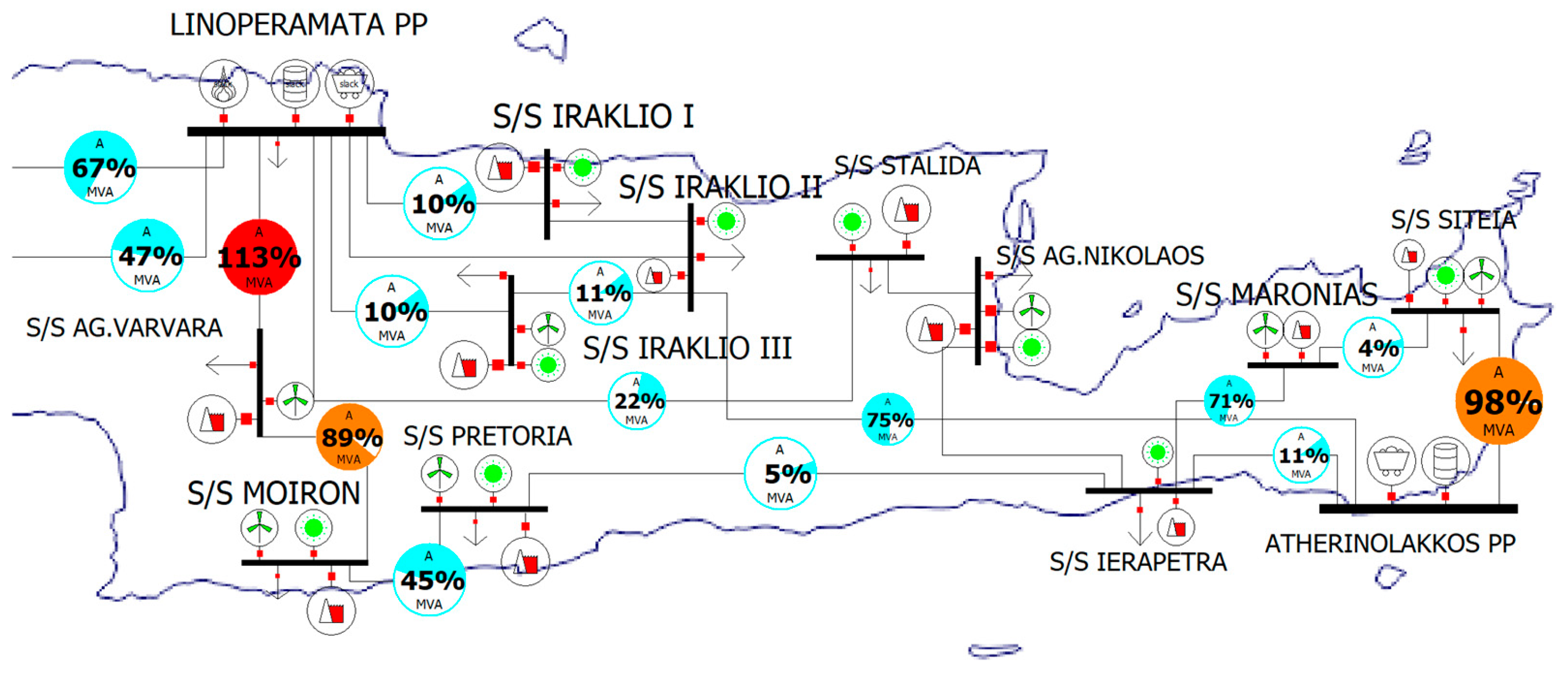

Figure 1 shows these two interconnections, the high-voltage (HV) substations of the island (triangles with solid lines), as well as the planned new substations (triangles with dotted lines) [

10].

The main objective of this paper is to highlight the need for further integration of RES into the Greek power system in order to reduce GHG emissions. Equally important is demonstrating how and why ESSs are essential to achieving this goal. A key challenge lies in determining which RES technology photovoltaic or wind power should be prioritized and to what extent. By carrying out this analysis, the study identifies the most suitable combination of RES technologies and ESS characteristics for effective and sustainable integration into the power system.

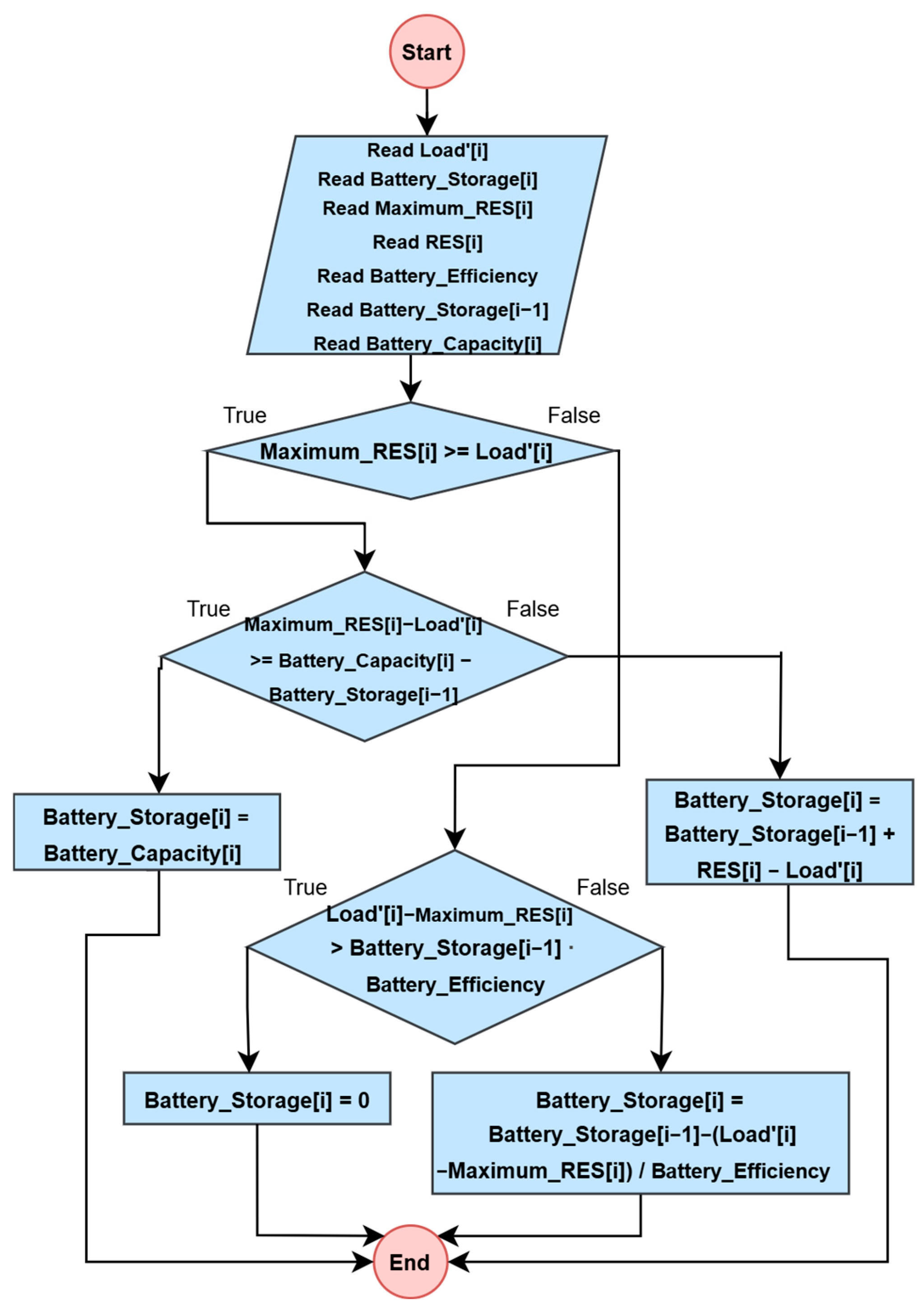

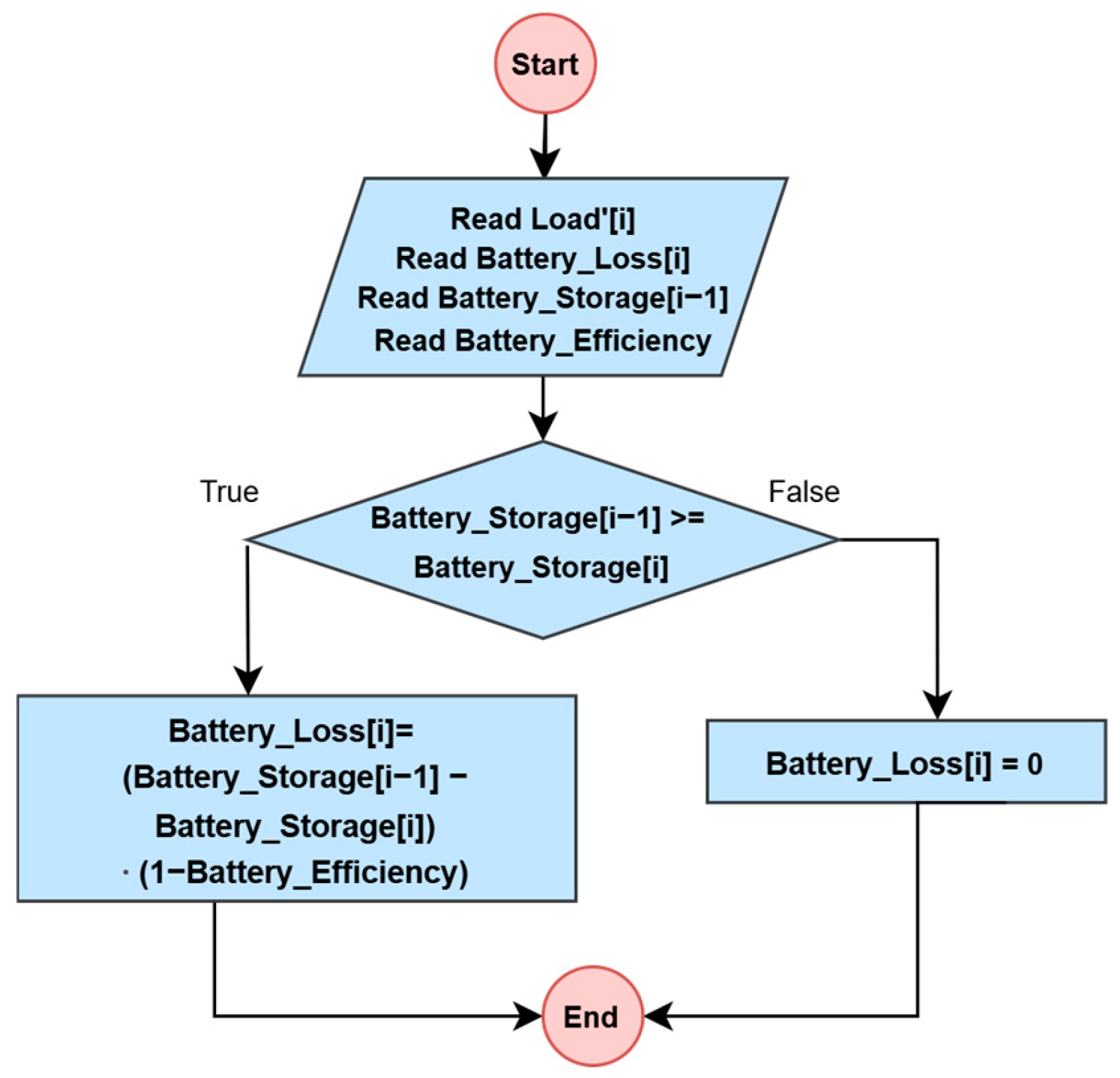

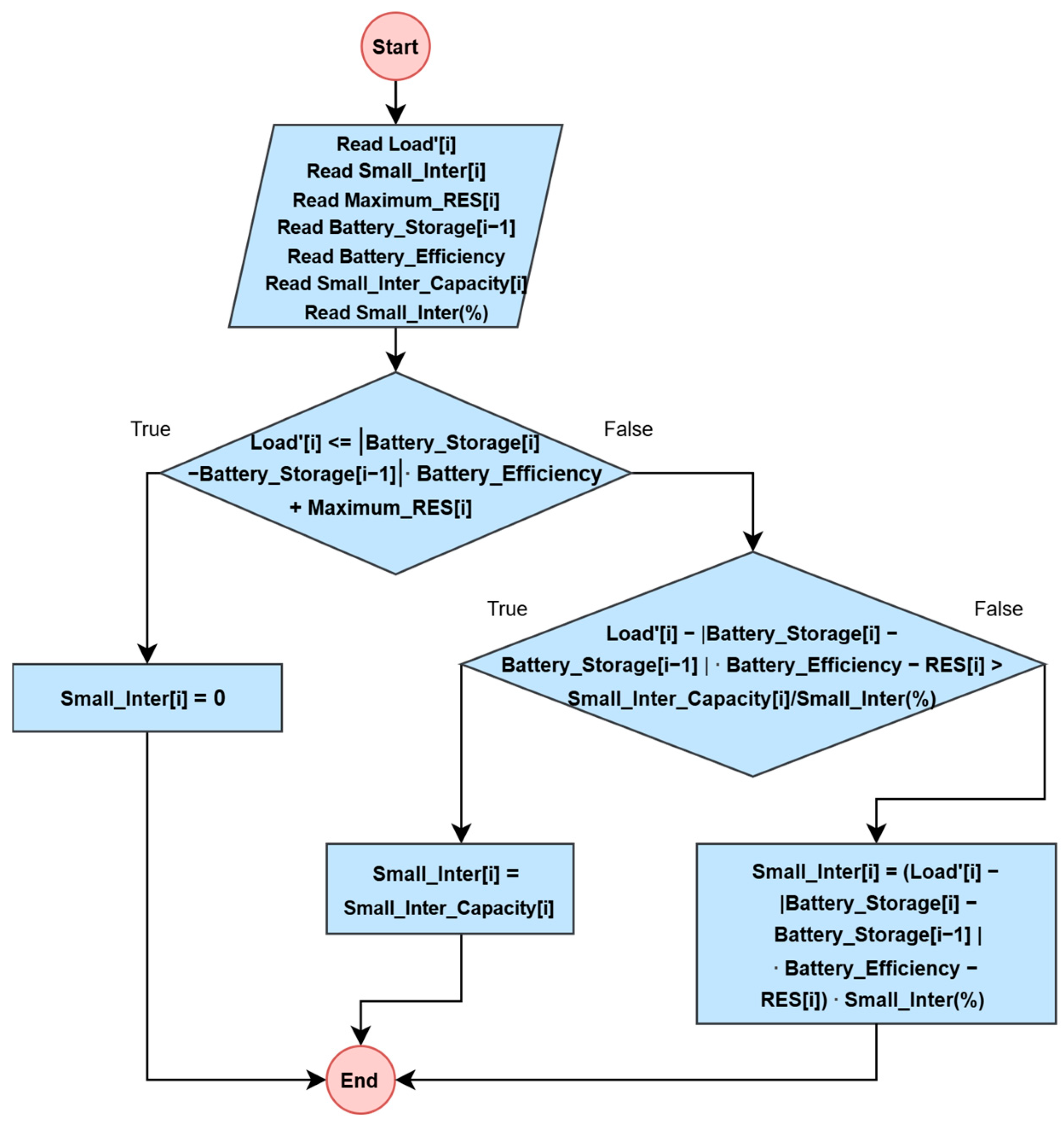

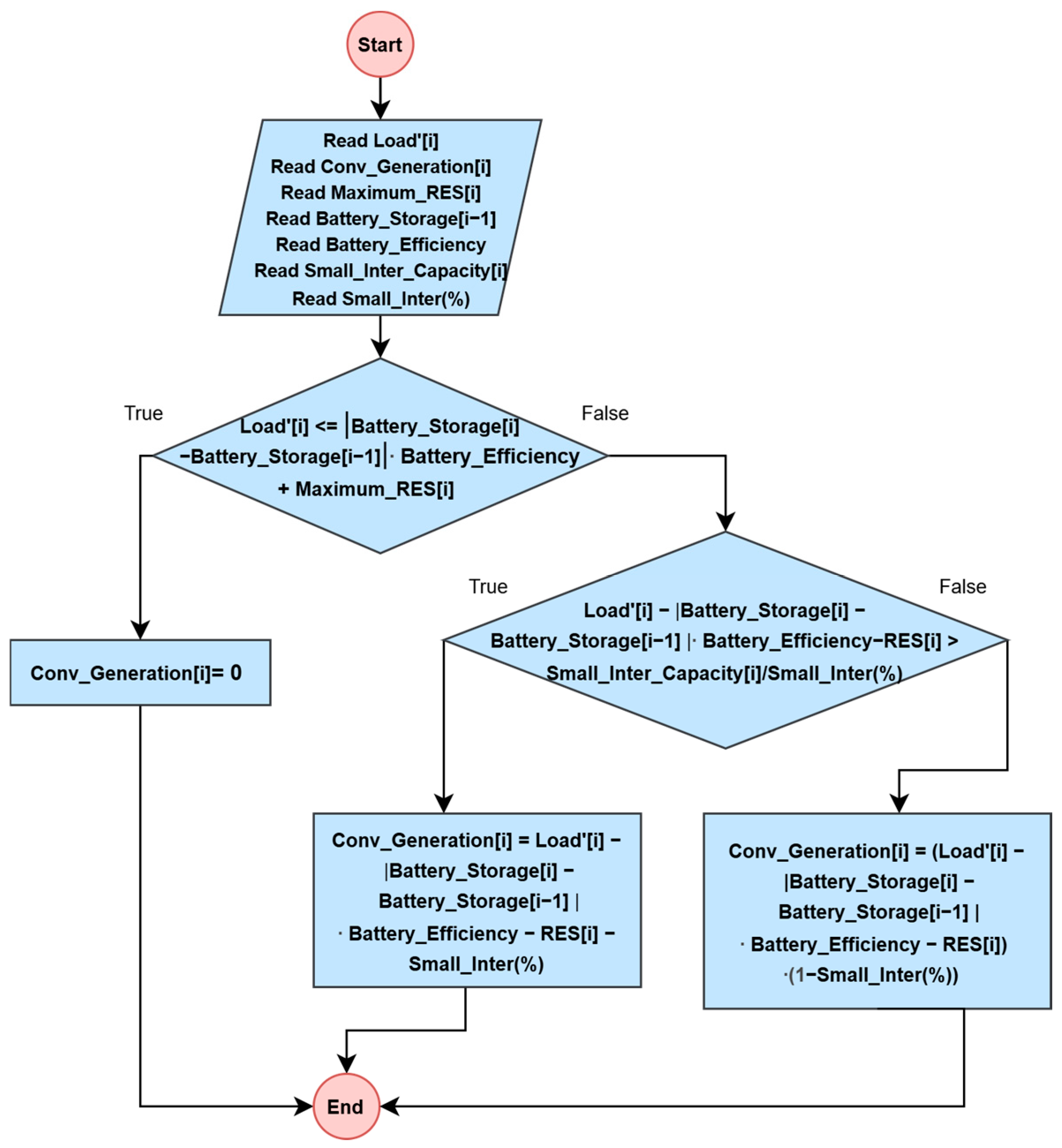

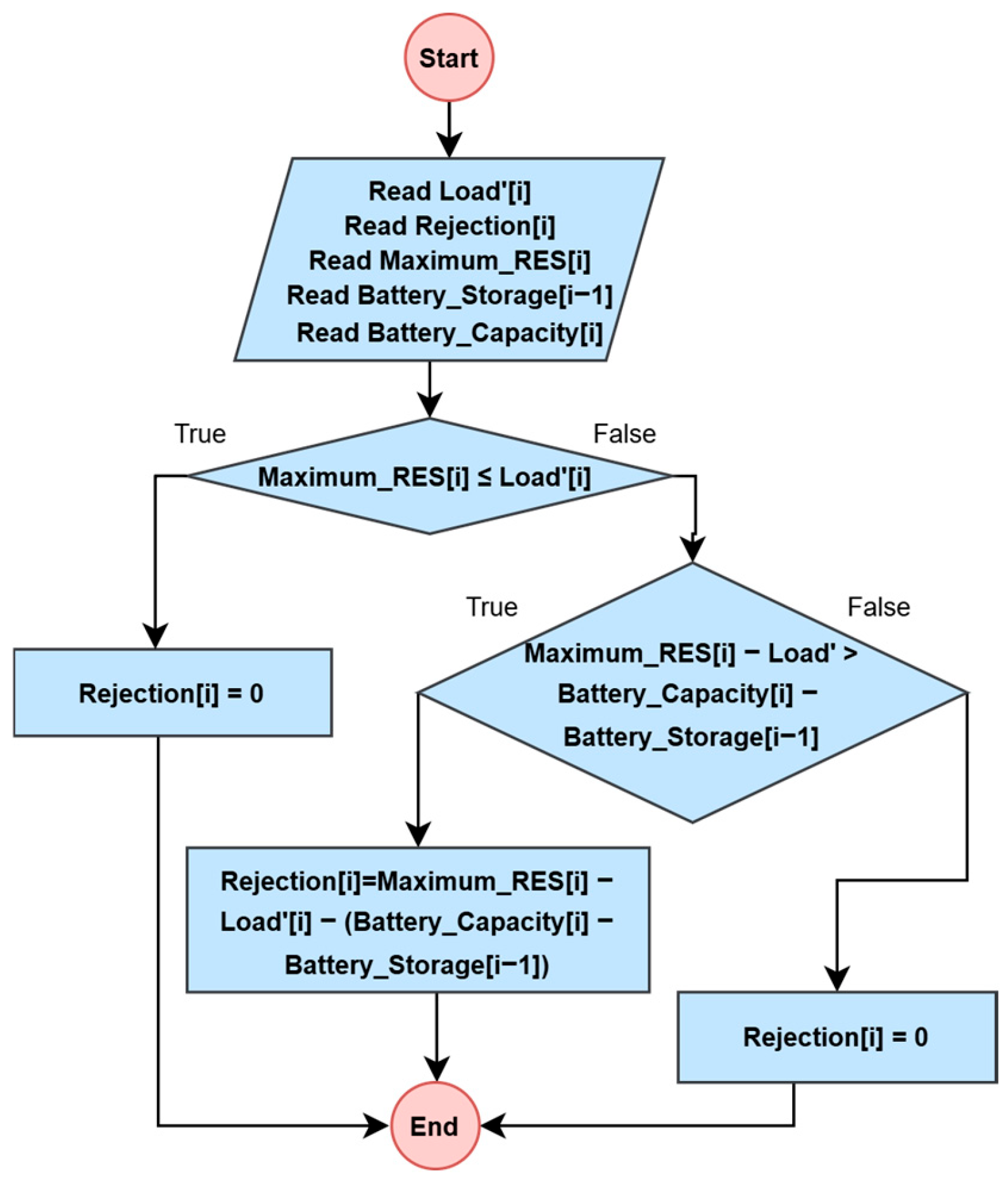

In the following section, four main scenarios are evaluated using the PowerWorld Simulator’s optimal power flow (OPF) algorithm for Crete’s HV power system over a one-year period. More specifically, the scenarios assume that installed RES capacity accounts for 35%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of the substation’s total power capacity, respectively. For each scenario, four sub-scenarios are evaluated: the first scenario reflects the current photovoltaic (PV) to wind turbine (WT) ratio; the second considers a 1:1 ratio; the third emphasizes PV capacity; and the fourth prioritizes WT capacity. For each sub-scenario, RES penetration is first assessed without battery storage. Battery storage is then introduced, and its capacity is progressively increased up to 12.8 GWh. Furthermore, several representative scenarios will be selected and simulated in the PowerWorld simulator (educational license, v.23, Champaign, IL, USA) using time step simulation, focusing on technical constraints and additional losses.

3. Results and Discussion

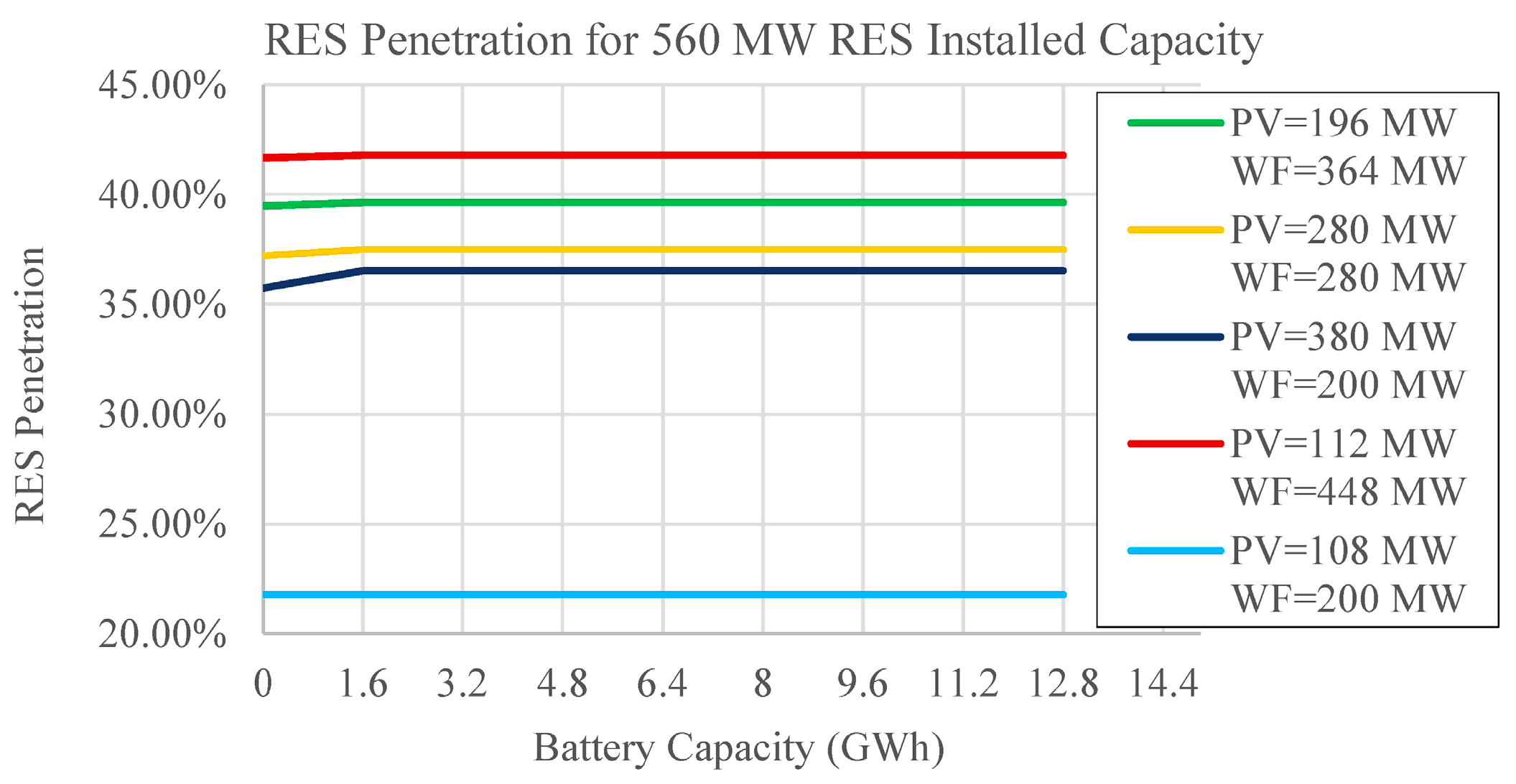

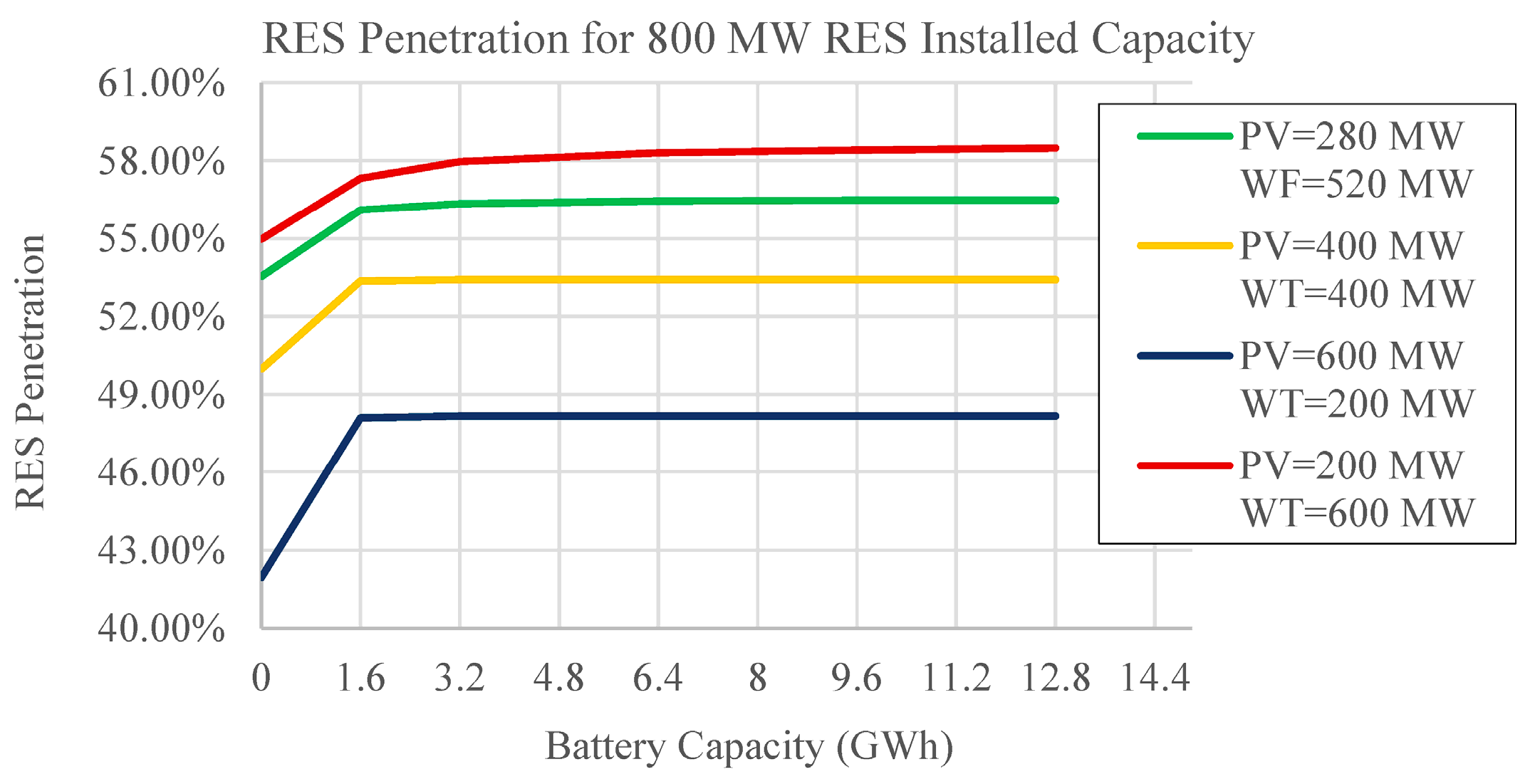

This section presents the results of the above scenarios. The following figures illustrate the RES penetration under different energy mix scenarios, the impact of BESS on curtailment reduction, the associated energy losses, and the loading of transmission lines. The first set of figures (

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) presents the RES percentage on total electricity generation for various storage capacities and different RES combinations between PVs and WFs. It is worth mentioning that the first set of figures does not account for the renewable energy generation in northern Greece, which is supplied to Crete’s power system via the small interconnection. The share of energy supplied through this interconnection ranges from 2% to 20% to Crete’s total demand, depending on the scenario. Considering that approximately 40% of this imported energy is produced from RES [

3], the total renewable energy contribution can be increased by a maximum of 16%, depending on scenario.

In

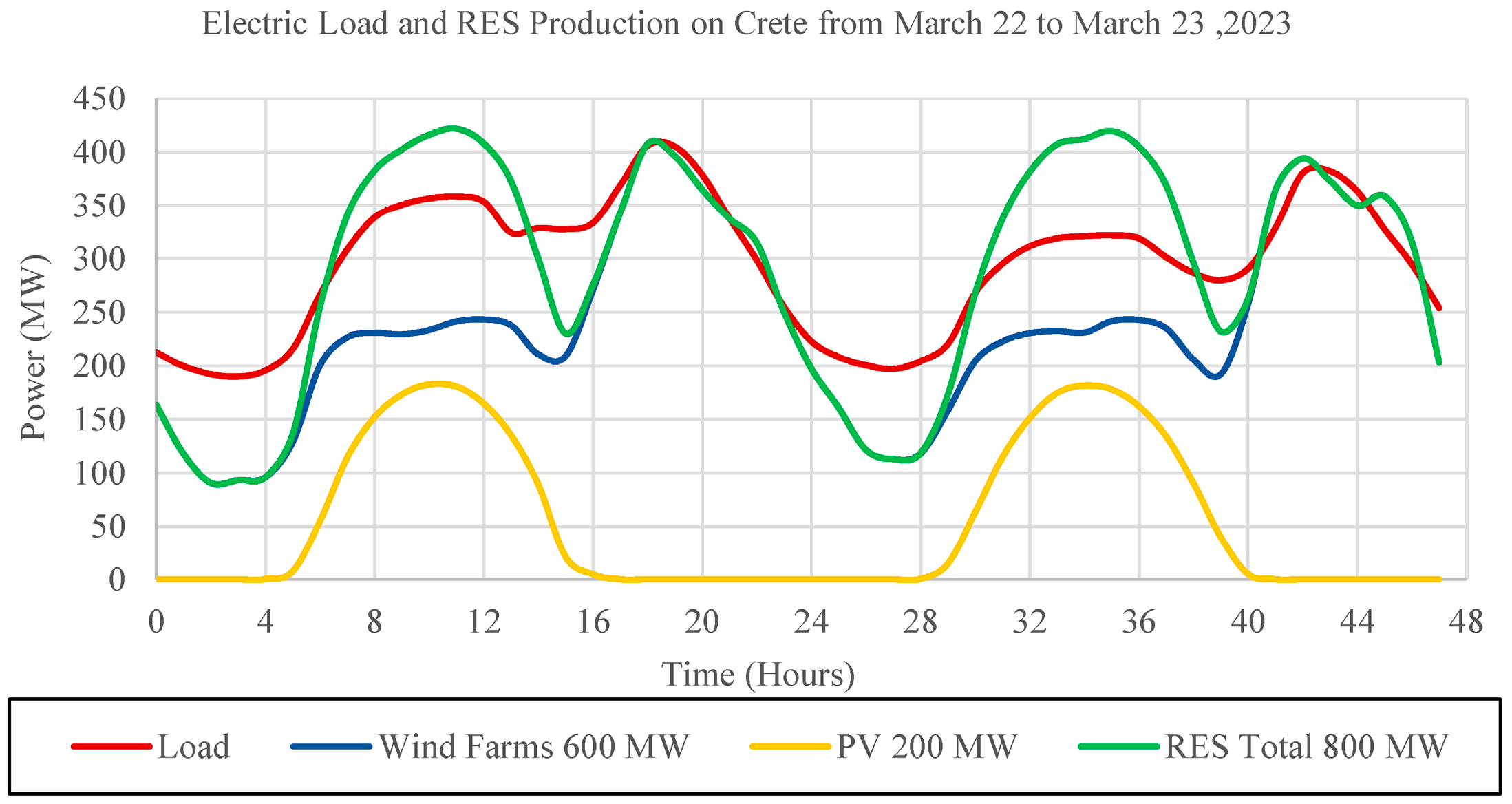

Figure 11, the first scenario is presented. In this scenario, the impact of energy storage is minimal since the energy produced from RES is almost always lower than the energy demand. The energy mix that focuses on WFs (red line) has an overall better penetration which can be attributed to its power generation curves, as previously illustrated in

Figure 2. Additionally, in

Figure 11, the current energy penetration from RES is also depicted (light blue line).

In

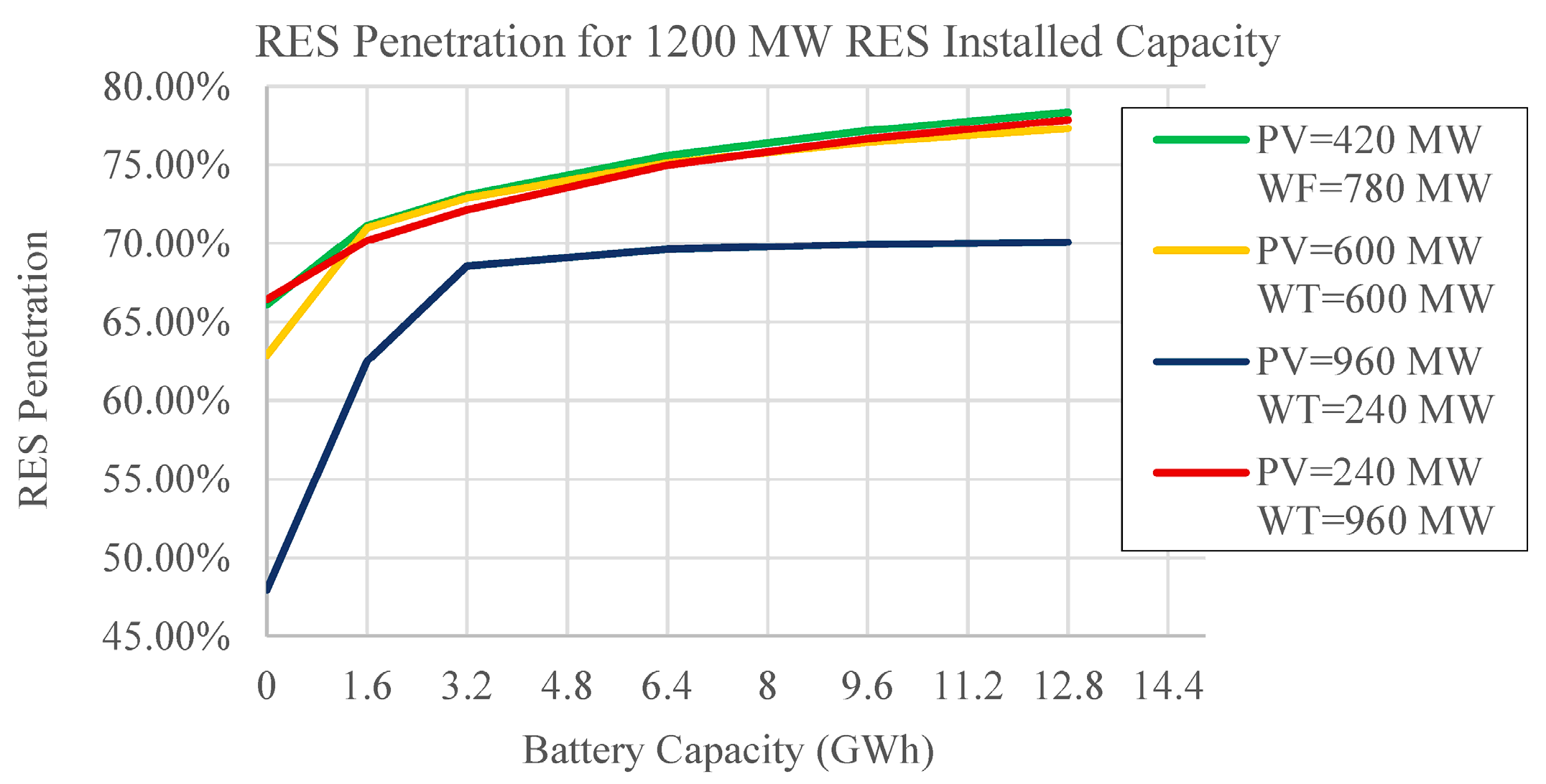

Figure 12, the second scenario is presented, which illustrates the impact of BESS in RES penetration. An ESS with a capacity of 1.6 GWh can reduce energy rejections and further increase the RES penetration by 6% in the sub-scenario that emphasizes generation via PV (blue line). Moreover, increasing the BESS capacity beyond this point yields only marginal improvements in RES penetration and is therefore not economically justified when considering the associated installation, operation, and maintenance costs. It is also important to note that, as in the previous scenario, the sub-scenario that focuses on wind energy (red line) rather than solar energy (blue line) can increase RES penetration by 13% for reasons that were mentioned in Scenario 1.

Figure 13 presents the results for Scenario 3. There are two key differences between Scenarios 2 and 3. First, a 6.4 GWh BESS is identified as optimal due to the higher levels of energy curtailment. Second, in this scenario, a wind-dominated energy mix is no longer clearly the most effective configuration. All the sub-scenarios have comparable RES penetration levels when BESSs are included, except for the sub-scenario that focuses on PV (blue line) which shows significantly lower penetration than the rest of sub-scenarios. This suggests that, in order to increase RES penetration in Crete’s energy mix, the installation of RES technologies should primarily focus on WFs, followed by additional PV capacity expansion.

In

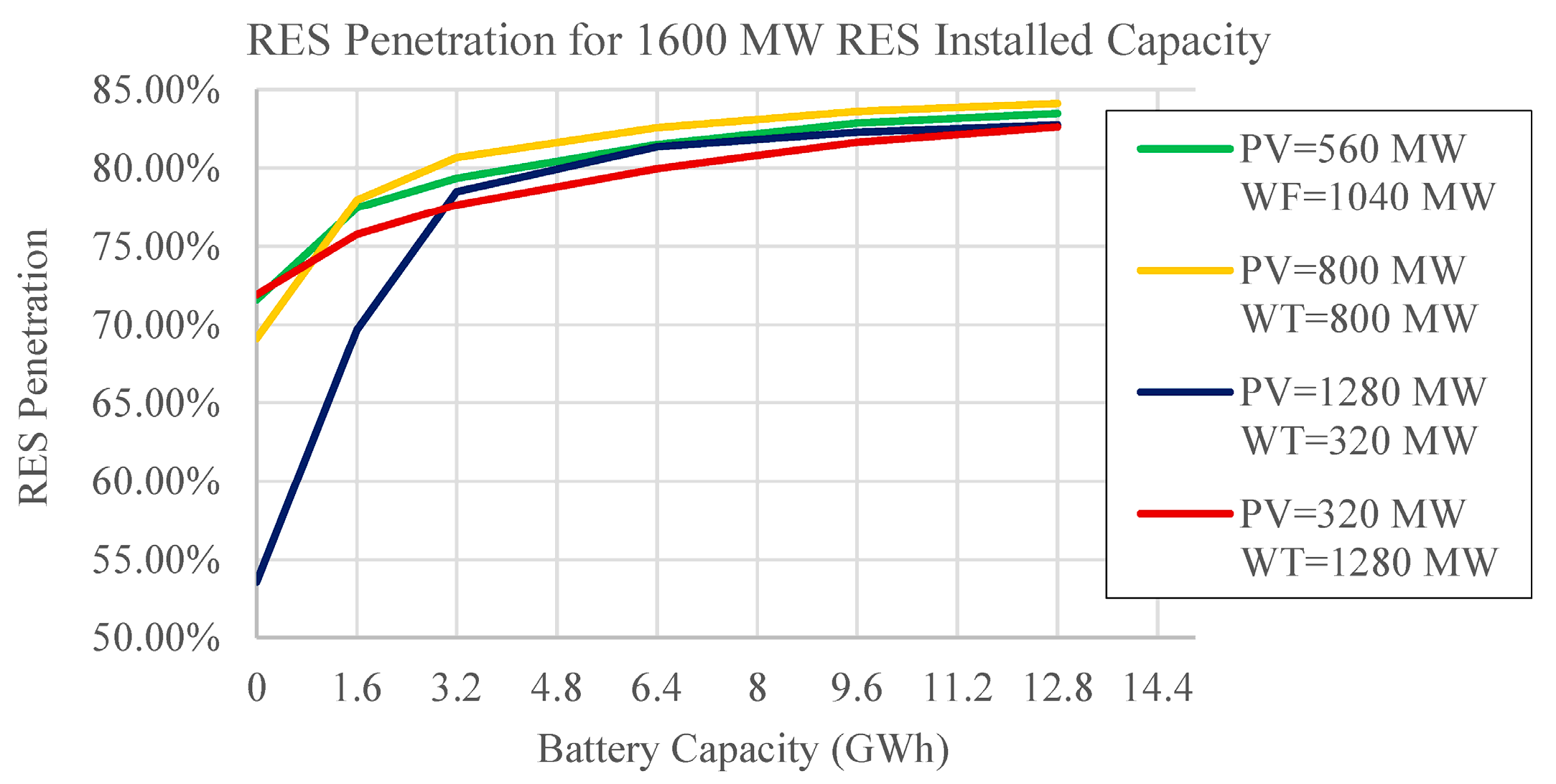

Figure 14, the final scenario is depicted. In this scenario, the RES penetration converges to approximately 82%, regardless of the sub-scenario. The optimal storage capacity ranges between 6.4 GWh and 9.6 GWh. The BESS installation has more impact on the sub-scenario that focuses on solar energy (blue line), leading to a further 28.07% increase in RES penetration. It is important to note that RES penetration cannot exceed approximately 85% due to system stability reasons and the requirement for reactive power, which is primarily provided by synchronous generators such as conventional units. WFs and PV systems cannot supply sufficient inertia and are almost incapable of generating reactive power.

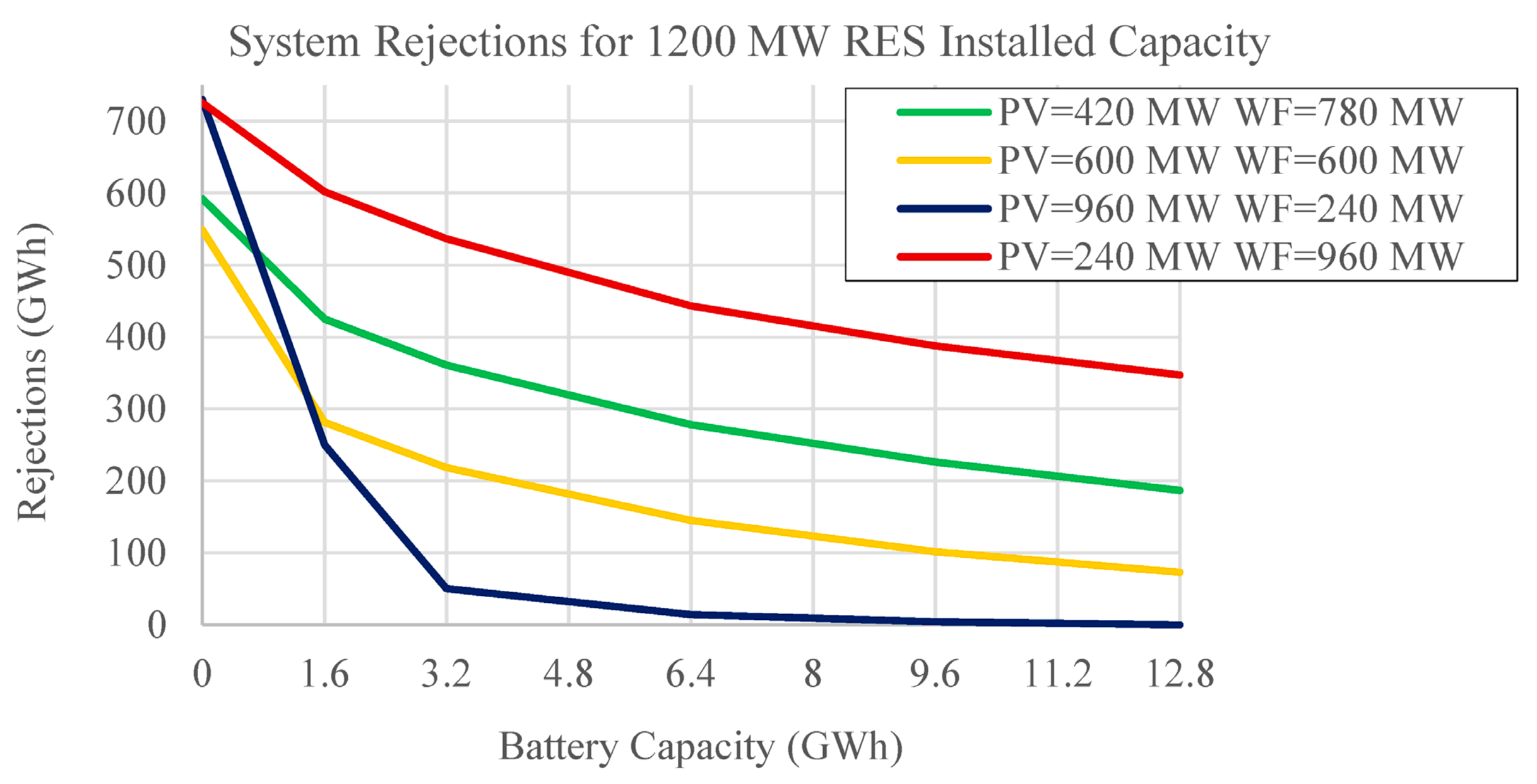

Furthermore, to better understand the effect of storage capacity on renewable energy utilization,

Figure 15 presents the curtailed energy of Scenario 3. In this figure, the impact of BESS in reducing energy curtailment can be observed, as a 9.6 GWh BESS has the potential to store and utilize up to 700 GWh of energy that would otherwise be dissipated.

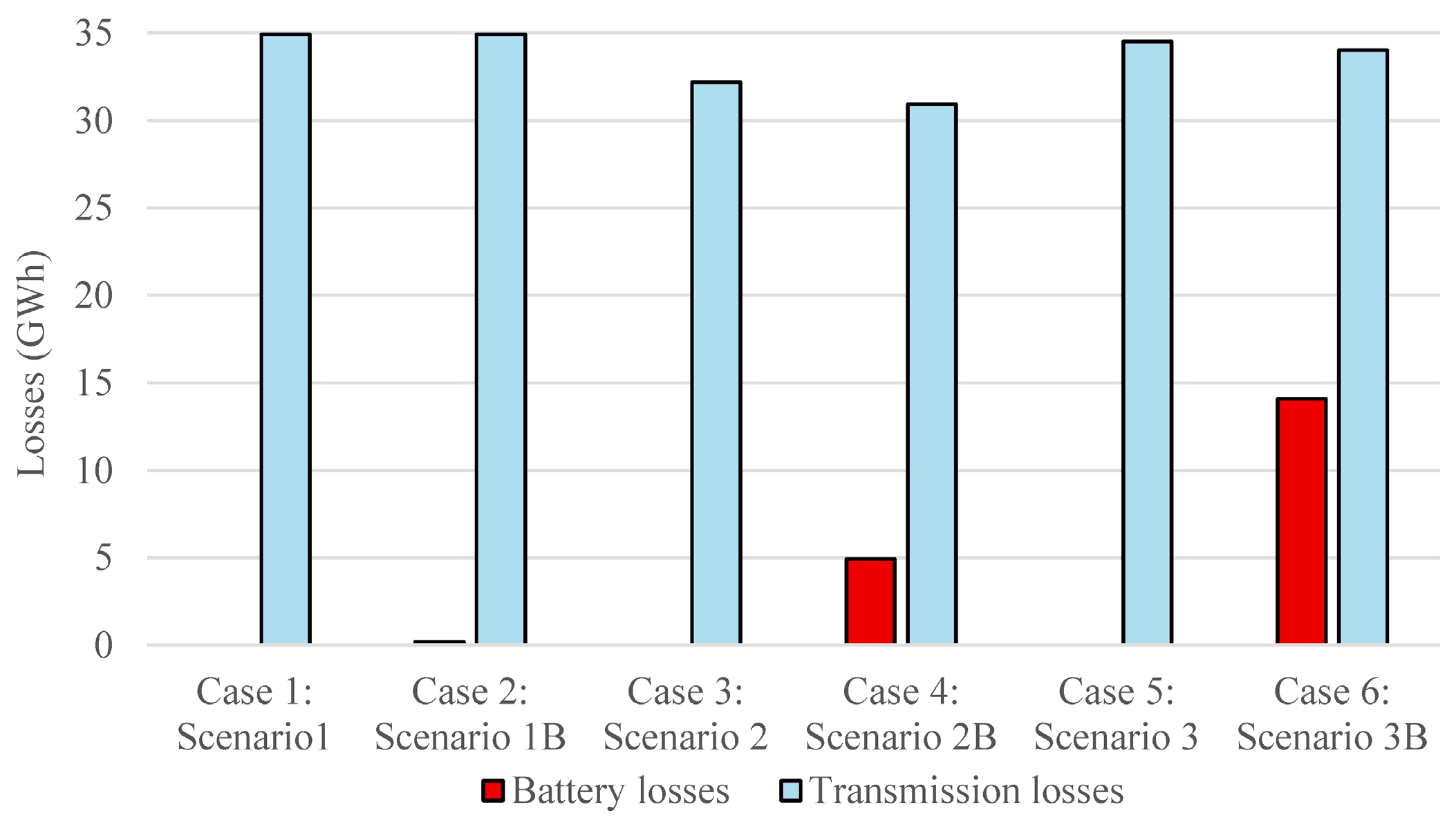

In the following figures, energy losses and transmission constraints will be depicted based on six specific cases. Two cases were implemented for each of Scenario 1, Scenario 2, and Scenario 3. The first case of each scenario does not include a BESS, while the second incorporates a BESS with optimal capacity. The corresponding optimal capacities were 1.6 GWh, 3.2 GWh, and 6.4 GWh for Scenarios 1, 2, and 3, respectively, as determined from results presented in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. In all cases, the generation mix emphasizes wind power, reflecting the higher penetration of RES.

Figure 16 presents the system loss results obtained from the PowerWorld simulator. In all simulation cases, the addition of a BESS reduced transmission losses, as expected [

11]. However, despite the decrease in transmission losses, the total system losses increased due to higher utilization of the storage system.

After analyzing the system losses under different cases, the next step focuses on the loading of transmission lines, as illustrated in

Table 3. The line loading for each case was calculated via PowerWorld’s time step simulation analysis. The table represents the number of instances where the line exceeds specific thresholds, such as 80% and 90% of their rated capacity. When a line loading exceeds 80% of its capacity, there is an increased risk for faults; more specifically, the lines can sag and potentially short-circuit with adjacent lines [

12]. In

Table 3, it is also calculated when the line limits exceed 100%. In the PowerWorld simulation environment, it is possible to analyze instances where the line loading surpasses 100% without immediately considering it as a fault. This approach helps identify situations where a line may require an increase in capacity in future system planning.

In

Table 3, it can be observed that increasing RES installations without a BESS reduces the number of instances in which line loading exceeds 80%. However, when a BESS is included, these instances increase, as the power flow is altered to store excess RES energy in other buses. In Case 6, this increase is particularly pronounced. This behavior was expected because the energy produced by RES is abundant, and the power system must accommodate it. Moreover, the system is primarily designed to transfer energy from conventional power plants to the loads, rather than from RES generation dispersed across the island.

In

Figure 17, a screenshot from PowerWorld simulation is represented in August 2023 at 13:00. In this figure, the lines connecting Moires–Ag. Varavara–Linoperamata, and Siteia–Atherinolakos–Iraklio II are the ones that are overloaded. These lines are the ones that become overloaded in the simulation, due to the abundant RES generation in Siteia, Moires, and Ag. Varvara. More precisely, RES generation exceeds both consumption and local BESS capacities, which results in excess energy directed towards the city of Heraklion (capital of Crete), covering the large loads and charging the local batteries to mitigate feature instabilities. In other words, the excess energy is transmitted through certain lines that do not have adequate capacity, leading to their overloading.

4. Conclusions

The increase in renewable energy generation is mandatory to fight climate change. Energy storage systems should accompany this increase with optimized capacities. In this research, the island of Crete was examined via the PowerWorld simulator. Different cases were constructed for different RES power generation, for various renewable generation mixes and different storage capacities. These cases proved that the increase in RES generation minimizes the need for conventional generation up to 28%, thus reducing GHG emissions. Moreover, it has been proven that the growth of RES should be complemented by energy storage systems. Their optimal capacities, which depend on the level of RES penetration, range from 1.6 GWh to 6.4 GWh per HV substation. Furthermore, Crete’s power system should prioritize wind energy, followed by solar energy. Additionally, the capacities of specific transmission lines must be carefully considered to accommodate the anticipated growth in renewable energy generation. Future research could also include the big interconnection in Crete’s power system and consider exporting energy to mainland Greece through both interconnections. Another aspect that could be examined is the effect of different RES technologies, such as green hydrogen, for both generation and energy storage.