1. Introduction

Modern lower-limb prosthetics are one of the key areas of biomedical engineering and orthopedic technology. Loss of ankle-joint function due to trauma, disease, or amputation markedly reduces locomotor activity, independent mobility, and overall quality of life. The ankle joint provides body stabilization, shock attenuation, and motion in three planes; its restoration or replacement requires rigorous biomechanical justification and engineering accuracy.

A current trend is the modularity of prosthetic designs: rapid replacement and adaptation of components to operating conditions, amputation level, physical activity, and individual patient characteristics. This approach simplifies servicing, accelerates fitting, and increases system reliability.

Despite the availability of commercial solutions for foot and ankle prosthetics, many are limited in functionality or remain too expensive for widespread adoption. The accessibility problem is especially evident in healthcare systems with constrained budgets and infrastructure. According to international organizations, more than 2.5 billion people require at least one assistive product, and access ranges from ~3% in some low-income countries to ~90% in certain high-income countries [

1,

2]. These figures underscore a pronounced global inequality in access to assistive technologies.

In response, the World Health Organization launched the GATE initiative (Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology), which coordinates global efforts to expand access to affordable, high-quality assistive products; its activities are structured by the “5P framework” (People, Policy, Products, Provision, Personnel) [

3].

Against this backdrop, the development of a modular ankle–foot prosthesis that combines engineering simplicity, biomechanical correctness, and flexible tuning is a timely task of applied engineering and social medicine. In addition, modern CAD tools and additive technologies enable accelerated design, reduced manufacturing cost, and enhanced personalization through the digital “scan–model–print” pipeline, as evidenced by the growing body of research on 3D-printed orthoses and prostheses [

4,

5,

6].

2. Materials and Methods

Modern ankle–foot prosthetics evolve along two intersecting axes: by energetic behavior and by mechanical architecture. Energetically, devices include passive energy-storing-and-returning (ESAR) carbon feet, in which compliant geometry accumulates and releases part of the step energy; semi-passive solutions with viscoelastic (often hydraulic) damping; and active (powered) designs with actuation and control [

7]. Architecturally, alongside monolithic (or low serviceability) systems, modular constructions are increasingly common, where the foot, ankle unit, and pylon interface are replaceable blocks. Modularity simplifies servicing, accelerates personalization of stiffness and damping, and lowers life-cycle cost—critical under budget constraints and when frequent tuning to user activity is required [

8]. To illustrate this spectrum, three representative exemplars are referenced: a classic passive ESAR foot (

Figure 1a), a semi-passive hydraulic ankle system (

Figure 1b), and a high-energy-return carbon sport foot (

Figure 1c). These examples highlight the compromise among simplicity, damping, mass, and tunability [

7,

9,

10].

Modular approaches appear both in open, low-budget 3D-printed feet and in research-grade active prostheses with multiple degrees of freedom. In open/printed prototypes, modularity is achieved by separating the compliant foot from the load-bearing ankle block and by using a standardized pylon interface; mechanical characteristics are tuned via interchangeable elastic elements and geometry variations of printed parts [

11,

12]. In recent active designs, modularity is expressed in mechanics (replaceable links and gear trains, independent damping channels) and in sensor/electronics layout, facilitating adaptation to gait scenarios and benchtop validation [

9,

13,

14]. For clarity, the target design’s modular scheme is shown as an exploded CAD view with three highlighted blocks—compliant foot, ankle unit with spring–short-stroke-actuator damper, and pylon adapter (

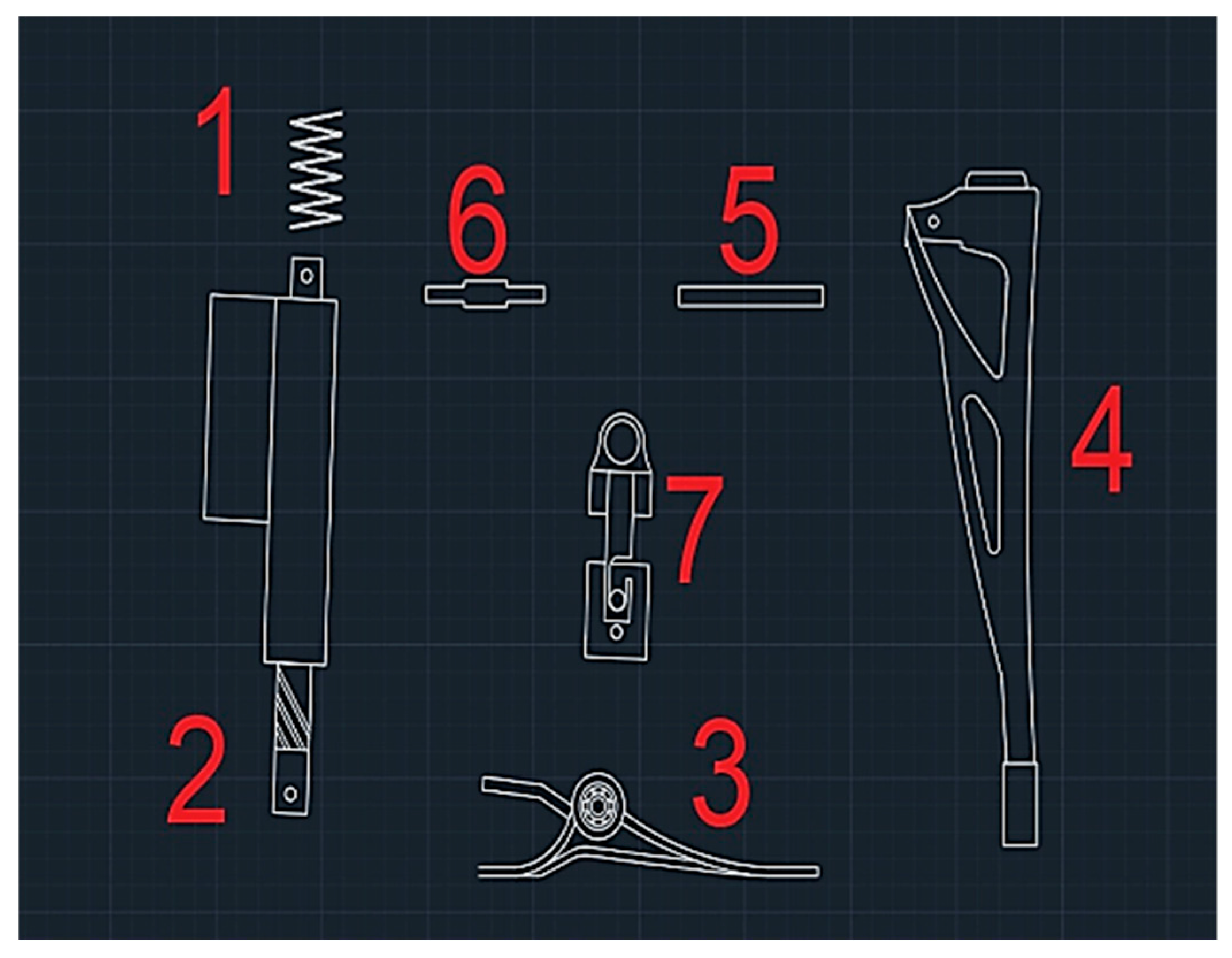

Figure 2) [

15,

16,

17].

This formulation aligns with studies on compliant 3D-printed feet with targeted nonlinear stiffness and with evidence on how damping/stiffness parameters affect gait-phase behavior in simulations and tests [

11,

14,

17]. The target prosthesis is specified by biomechanical assumptions and manufacturing constraints. The adopted angular ranges are ~15–20° dorsiflexion and ~40–45° plantarflexion, with lateral compliance to accommodate uneven terrain. A consolidated schema of gait phases, ground-reaction directions, and the role of the musculo-ligamentous system underpins the choice of load cases and required compliance. Based on these premises, the architecture comprises an S-shaped compliant foot for energy storage/return in mid-stance and toe-off, and an ankle unit with a parallel branch “spring + short-stroke linear actuator” providing adjustable damping and preload for smoother heel-strike attenuation. The manufacturing platform targets FDM: PETG is chosen for its balance of processability, toughness, and moisture resistance; for higher duty use, nylon-CF and high-temperature thermoplastics (PEI/PEEK) are considered [

11,

12]. Load-bearing bores are reinforced with metal bushings; threaded joints are unified for standard tools. A consolidated bill of materials (polymers, fasteners, bushings, springs, actuator, approximate masses) is summarized in

Table 1.

The FDM workflow on a desktop Bambu Lab P1S (Shenzhen, China) included geometry preparation with minimal support (rational split planes, 2.5 mm internal radii, chamfers), a 0.6% PETG shrinkage compensation, and layer orientations that align in-service tensile paths with perimeters rather than interlayer bonds. Baseline printing parameters were a 0.20 mm layer height, five perimeters, 35% infill, a 245 °C nozzle temperature, and an 80 °C bed temperature, consistent with current practice for functional prosthetic FDM parts with controlled anisotropy and tolerances [

11,

12].

Finite-element analysis (FEA) covered three characteristic regimes: mid-stance with vertical load

; heel-strike with an added posterior shear

; and toe-off with an anterior shear of the same magnitude and the center of pressure shifted toward the forefoot. The pylon interface was modeled as a hinge with one rotational degree of freedom (dorsi/plantar flexion) and five constrained degrees of freedom; a fixed variant was also evaluated to probe mounting stiffness. Bolted joints and bushing zones were assigned bonded contacts, and the support plane was treated as ideally rigid. PETG was modeled as linear elastic with

and

; to reflect FDM anisotropy, a conservative allowable stress

was applied to the as-printed material [

12]. The mesh comprised tetrahedra (base size 2.0 mm) with local refinement to 0.8 mm near holes, fillets, and interfaces; convergence was enforced when the peak von Mises stress changed by <5% between successive refinements.

The spring–actuator branch was tuned to a target force–displacement response during stance and to guarantee neutral return during swing. The branch was assumed to carry 25% of peak ; the spring stiffness followed with , and a 60 N preload was used to eliminate backlash and shape the initial response.

The experimental program comprised visual inspection and fit-up, stepwise static loading up to 1100 N (≈1.5 BW for 75 kg) with 10 s dwell per step while recording toe deflection and damper-node strains, a screening fatigue run of 20.000 cycles at 2 Hz and 300 N amplitude, and phase-mimicking load placements (heel-strike/mid-stance/toe-off) with force–displacement loops captured. Data processing used ≥3 repeats, 95% confidence intervals, and Tukey outlier rejection (1.5 IQR). The test-rig configuration and emulation approach are consistent with peer-reviewed prosthetic-foot emulators and platforms [

13].

Recent advances in ankle–foot systems follow three principal directions: (i) powered ankles that target controlled torque and push-off work; (ii) semi-active or variable-stiffness feet that modulate damping and stiffness with minimal mass and energy cost; and (iii) additive-manufactured, low-cost prostheses aimed at accessibility and rapid personalization. Powered ankles provide high control authority at the expense of complexity: a recent two-degree-of-freedom powered ankle–foot reported sub-50 ms step response at ~40 N·m per actuator and validated untethered level-ground walking, underscoring the performance potential alongside increased mass and power-management demands [

9]. Semi-active concepts pursue adaptability without full actuation; a model-based study of a two-keel variable-stiffness foot (VSF-2K) indicated that independently modulating hind- and forefoot stiffness improves phase-dependent metrics while preserving passive-foot envelopes, supporting the rationale for tunable mechanical elements in affordable devices [

18].

On the manufacturing side, AM/FDM routes reduce cost and lead time while enabling scan-to-print personalization; however, recent reviews emphasize the need for standardized as-printed material data (anisotropy, fatigue) and consistent clinical outcome reporting. A 2025 systematic review of 3D-printed prostheses reported improvements in comfort, gait parameters, and fit, while highlighting the need for durability reporting and protocol harmonization [

19].

In parallel, sensor integration that combines IMU, plantar-pressure, and angular sensing with lightweight control has been shown to improve phase detection and damping control without the full burden of powered actuation; contemporary surveys outline practical sensor suites and control strategies relevant to semi-active branches [

20].

Passive high-energy-return feet (e.g., carbon leaf/elliptical designs) remain efficient baselines, with recent biomechanical evaluations confirming strong energy-storage benefits but noting limitations in shock attenuation and terrain adaptivity that semi-active modules aim to address [

21].

Within this landscape, the present modular design—an S-shaped compliant foot with a parallel spring–short-stroke actuator—targets affordability and maintainability while enabling adjustable damping and preload, providing a pragmatic pathway toward subsequent sensor-assisted semi-active control.

3. Results and Discussion

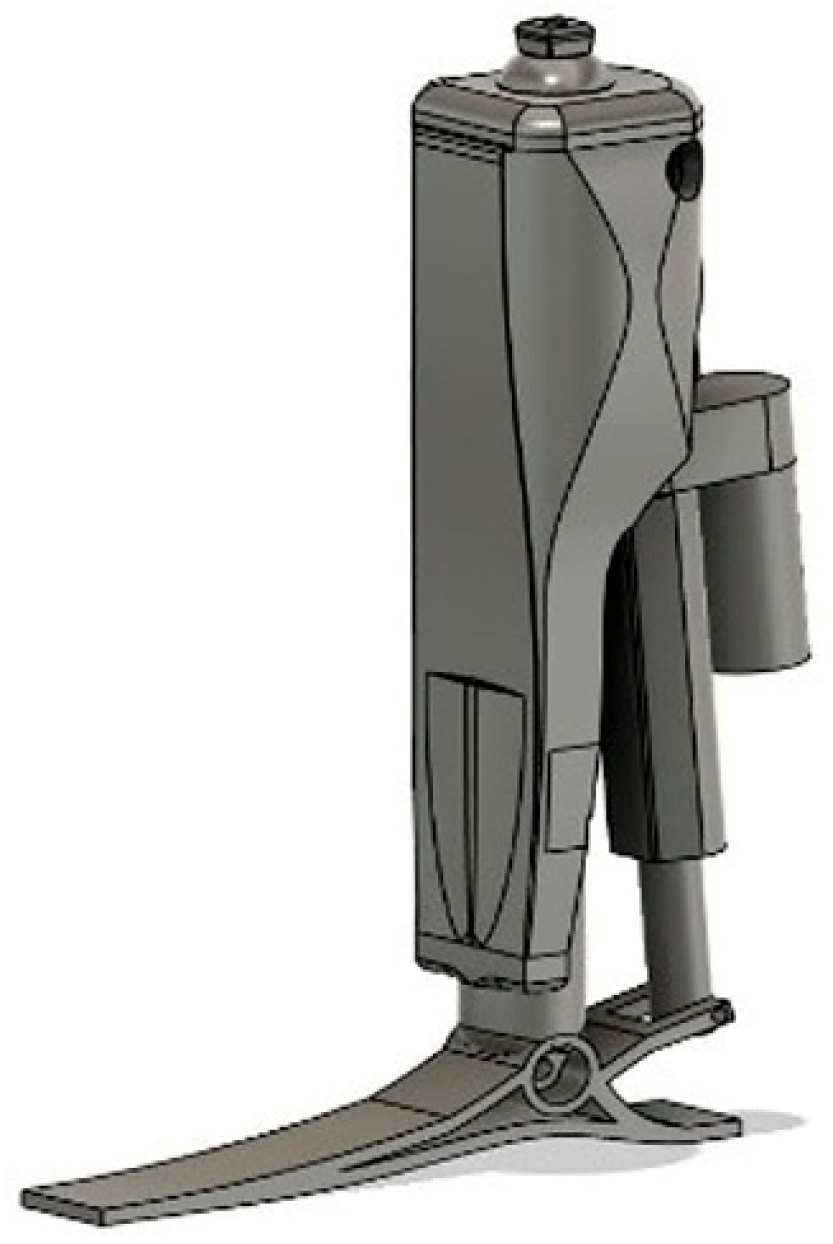

Preliminary sketching enabled a coherent modular architecture of the prosthesis and the identification of key geometric decisions prior to detailed CAD modeling. The layout separates the system into a compliant S-shaped foot, an ankle unit with a spring–actuator damper, a load-bearing housing, and an interface to the socket. The sketches refined axis locations, the kinematic linkage between the damping branch, housing, and foot, and manufacturable connector forms for FDM; force paths were assessed in parallel, allowing early assignment of appropriate internal fillets and locally reinforced zones (

Figure 3).

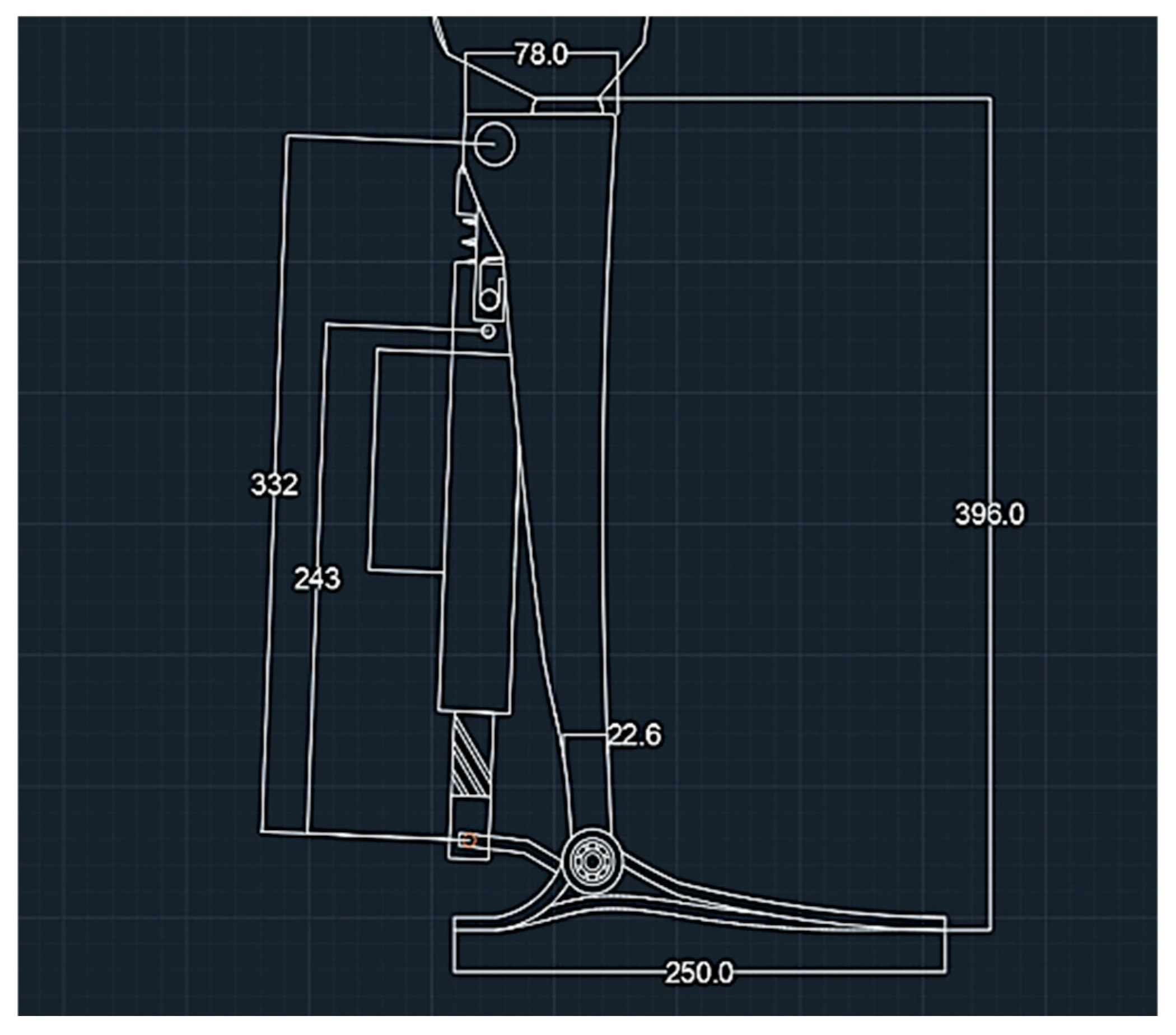

The final arrangement shows that the required sagittal mobility is achieved by a hinge joint where the damping branch (“spring + short-stroke linear actuator”) works in parallel with the foot’s compliant deformation. The housing is a load-bearing shell with unified seats for bushings and fasteners; the S-profile foot provides energy return during rollover and reduces the impact component of the ground-reaction force. The working drawing fixes overall dimensions and mounting interfaces for printing and assembly (

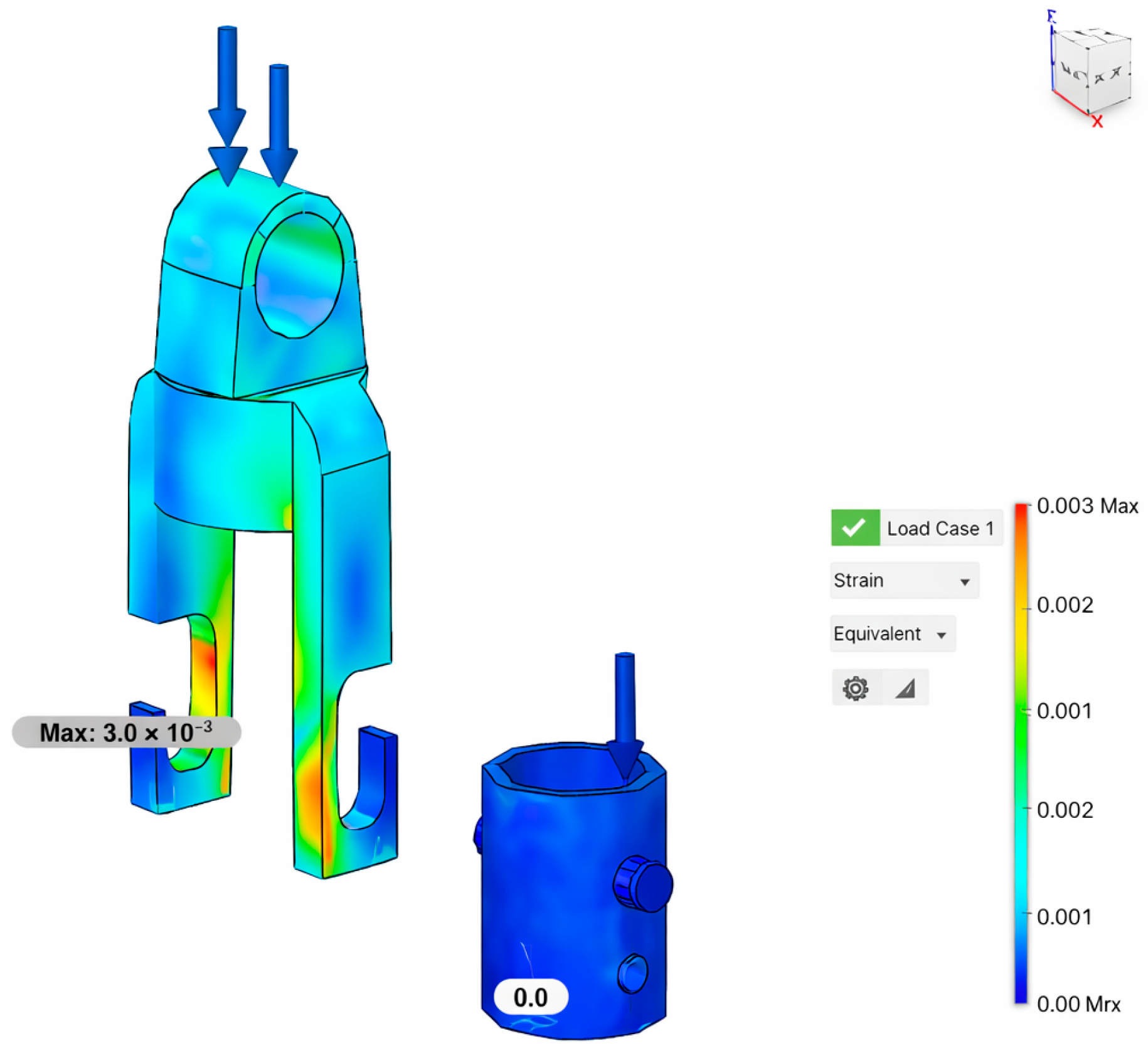

Figure 4). A 3D model was developed in Fusion 360. PETG was chosen for printed parts; load-bearing seats were reinforced with metal bushings; purchased components (linear actuator and spring) were selected by catalog. For comparability in numerical analyses, a single static load case F = 600 N was used as a representative vertical ground-reaction force in steady stance; boundary conditions mirrored real fixation (rigid support with bonded contacts in fastener areas for adapters/housing; fixed heel and applied load at the shank–foot junction for the foot).

In the Equivalent Strain formulation, deformation maxima localize at section transitions and threaded seats. The mapped value εmax ≈ 0.003 mm/mm confirms elastic behavior of “as-printed” PETG under the given load

Damper assembly (actuator + spring). Analysis showed uniform load sharing; expected concentrations occur at interfaces between purchased metal parts and printed brackets. The maximum mapped strain is ε

max ≈ 7.45 × 10

−5, consistent with the high stiffness of metal parts and correct force transfer through interface details (

Figure 5).

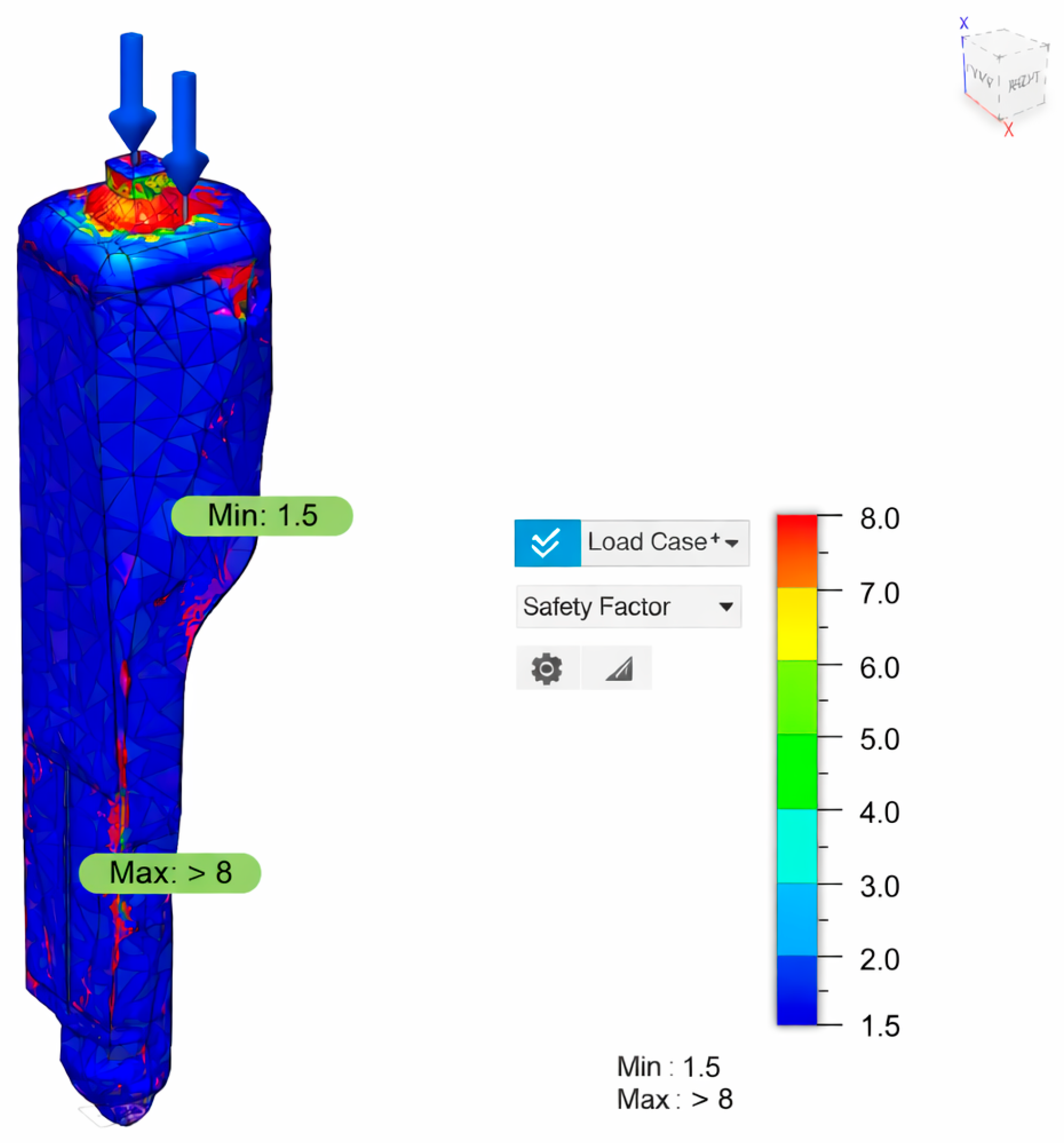

The safety-factor map shows no extended “warm” zones; the minimum calculated margin is K

min = 15, confirming the sufficiency of wall thicknesses and ribs for the static scenario (

Figure 6).

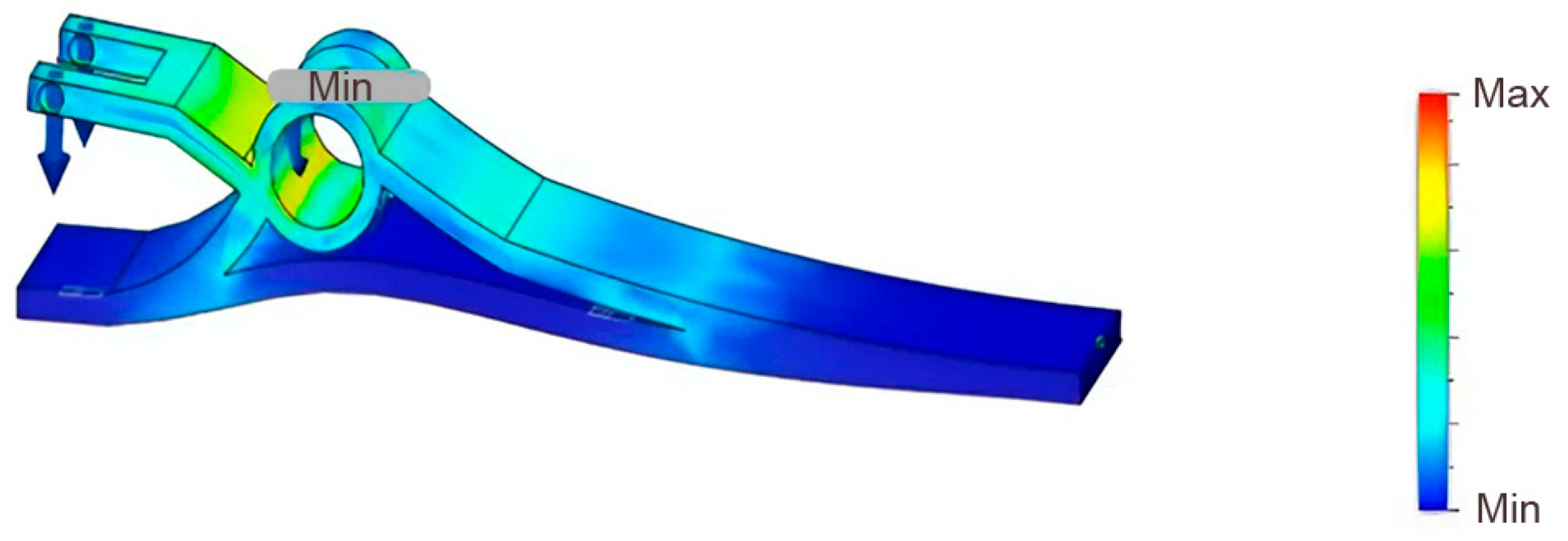

For the compliant foot (Equivalent Strain), ε

max ≈ 0.003 localizes in the hinge neck; the main plantar area operates in small elastic strains. This aligns with the S-profile’s target function-localized bending and energy return at toe-off with controlled compliance (

Figure 7).

The final render confirms interface consistency and modularity: the damper unit and foot are replaceable without modifying the housing, the pylon interface is standardized; tolerances correspond to FDM capabilities (

Figure 8).

Printed PETG elements (

Table 2) under

remained in the elastic regime with strain localized to target compliant zones

for the adapter and foot, whereas metal subassemblies showed substantially lower compliance

. The housing achieved

, confirming the adequacy of ribbing and material distribution. The combined set of sketches, general drawings, FEA outputs, and the final CAD assembly demonstrates consistent load paths and a layout manufacturable on desktop FDM equipment, with room for damping-parameter personalization.

The proposed modular architecture distributes the functions of individual components in such a way that the compliant S-shaped foot and the spring–actuator branch are responsible for localized bending, energy return, and damping, while the housing and interface joints provide geometric stiffness and positional stability. This decomposition not only simplifies structural optimization but also reduces the life-cycle cost: personalization of stiffness and damping is achieved through the replacement of accessible modules without interference in the load-bearing part.

The deformation patterns observed in numerical simulations correspond to the expected gait biomechanics: compliance is concentrated in target zones, while stress concentrations arise at section transitions and fastener joints. This confirms the validity of adopted geometric principles (enlarged radii, localized ribs, unified seats) and emphasizes the importance of “force-path-based design” in FDM manufacturing: layer orientation along perimeters, reinforcement with bushings, and reasonable restriction of monolithic parts where controlled bending is required. In this sense, modeling acts as a tool for identifying priorities-where to maintain compliance and where to reinforce locally without significantly increasing mass or printing time.

The study’s limitations are typical of an early stage: static load scenarios, linear-elastic models, and idealized contacts (

Table 3).

These provide a safe design corridor but necessitate further work, including fatigue and environmental testing, evaluation of interlayer strength under real printing conditions, and dynamic validation with phase-dependent gait load scenarios. Modular design, meanwhile, opens an evolutionary development pathway-from a semi-passive configuration toward a moderately active one by adding sensors and controlled damping, without altering joint geometry and with minimal iteration costs.

4. Conclusions

The proposed modular design of the ankle–foot prosthesis, combining a compliant S-shaped foot and a spring–actuator damping branch, demonstrated the ability to withstand a calculated static load of 600 N, ensuring controlled compliance, attenuation of impact forces, and the possibility of personalized stiffness adjustment through spring selection and preload tuning. The resulting mechanical pattern-localized bending in the toe region and a reduction of peak stresses after increasing transition radii and introducing local ribs aligns with the known advantages of compliant feet and 3D-printed nonlinear stiffness components.

Comparison with two-degree-of-freedom (2-DoF) powered ankle–foot systems shows that active solutions excel in controllable torque output and response speed, which is critical for targeted gait kinetics and adaptation to terrain and pace. However, these benefits come at the cost of significantly greater structural and algorithmic complexity, weight, energy consumption, and manufacturing expense. In this context, the presented modular variant is focused on affordability and maintainability: it provides passive–semi-passive energy return and damping with minimal requirements for component availability and manufacturing resources, is compatible with desktop FDM production, and supports user-specific customization.

The practical significance of this work lies in demonstrating an engineeringly realistic pathway to lowering access barriers while preserving key biomechanical functions (energy return during toe-off and impact absorption during heel-strike). The study’s limitations-static load modeling, linear-elastic assumptions, and idealized contacts-set the agenda for future research: fatigue and environmental testing of printed materials, evaluation of interlayer strength under real printing conditions, extended bench-top gait phase emulation with variable speed and incline, as well as investigation of the influence of preload and spring selection on subjective comfort. Collectively, the results allow the proposed modular architecture to be considered a technologically and economically viable foundation for accessible ankle–foot prostheses with potential scalability for specific clinical scenarios.