An Integrated Model for the Electrification of Urban Bus Fleets in Public Transport Systems †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Key Components of the Mathematical Model

- The total financial cost, or

- The carbon emissions and associated social-environmental externalities, while ensuring uninterrupted transport operations and meeting minimum service thresholds.

- Maintaining a minimum number of buses in operation;

- Annual budget ceiling;

- Charging infrastructure capacity;

- Gradual increase in the share of electric buses;

- Full electrification by the final period.

3.2. Mathematical Model

3.2.1. Parameters

3.2.2. Decision Variables

3.2.3. Constraints

3.2.4. Operational Costs

3.2.5. Carbon Emissions

3.2.6. Final Condition

3.2.7. Annual Replacement Capacity

3.2.8. Charging Infrastructure Capacity (Optional)

3.2.9. Objective Function

- Reduction in particulate matter (PM) emissions, which are critical pollutants with direct adverse effects on human health;

- Mitigation of traffic noise, particularly significant in densely populated urban areas;

- Direct social benefits, quantifiable through savings in public healthcare expenditures;

- Improved well-being and enhanced urban attractiveness, contributing to long-term livability.

4. Results and Discussion

- Tire wear;

- Brake wear (significantly lower than for diesel buses due to regenerative braking systems);

- Road dust resuspension.

- T = 10 (planning period in years);

- No = 20 (initial number of electric buses);

- Mo = 49 (initial number of diesel buses);

- Ce = 562,421 EUR (unit cost of a mid-range electric bus);

- Cd = 306,775 EUR (unit cost of a mid-range diesel bus);

- Oe = 16,291 EUR/year (annual operating cost per electric bus);

- Od = 30,166 EUR/year (annual operating cost per diesel bus, EURO V);

- Ee = 0 t CO2/year (CO2 emissions per electric bus);

- Ed = 77.4 t CO2/year (CO2 emissions per diesel bus, EURO V);

- PMe = 1.92 kg PM10/year (particulate emissions from electric bus/PM10);

- PMd = 19.2 kg PM10/year (particulate emissions from diesel bus, EURO V);

- Noisee = 0.3 (normalized noise index of electric bus);

- Noised = 1.0 (normalized noise index of diesel bus);

- αPM = 5112.92 EUR (value per unit reduction in PM);

- αNoise = 2556.46 EUR (value per unit reduction in noise).

- It = 511,291.88 EUR/year—annual investment in charging infrastructure;

- Bt = 5,112,918.81 EUR/year—total annual investment budget;

- Rt = 10 buses/year—maximum allowable annual replacements;

- α = 0.6. β = 0.4—weights in the objective function.

- identify the conditions under which the municipality can achieve an optimal balance between environmental, social and economic benefits;

- highlight risks and constraints that may hinder the implementation of electrification;

- support informed decision-making in an environment characterized by high uncertainty and interdependent factors.

Example Scenarios

- increased investment budget: Bt = 7,670,000 EUR/year;

- weights in the objective function: α (environmental indicators) = 0.4. β (financial indicators) = 0.6.

- rapid replacement of diesel buses—achieving 100% electrification as early as 2030;

- higher upfront investments but substantial long-term environmental benefits.

- reduced budget: Bt = 3,066,000 EUR/year;

- bus prices: No change.

- delayed electrification with full replacement achievable only after 2040;

- risk of additional costs due to an aging fleet and increased emissions.

- Ce = 664,679.40 EUR (approx. 18% increase);

- budget Bt = 5,115,000 EUR/year.

- fewer buses can be replaced each year;

- need to revise timelines or the weights in the objective function.

- αPM = 7670 EUR; αNoise = 4090 EUR;

- priority given to reducing noise and particulate matter pollution.

- higher social value attributed to electrification;

- earlier replacement of buses in sensitive areas (city center, residential neighborhoods, schools).

- Bt = 6,134,000 EUR of which 60% comes from the Recovery and Resilience Plan (European fund);

- Ce = 562,700 EUR after discounts from group purchases;

- CO2 emissions valued at 102 EUR/t CO2.

- replacement of 60% of the fleet by 2033;

- emission savings are also accounted for in the municipal budget.

- Rt limited to 5 electric buses/year.

- prolonged use of old diesel vehicles;

- reassessment of emission values and replacement timelines.

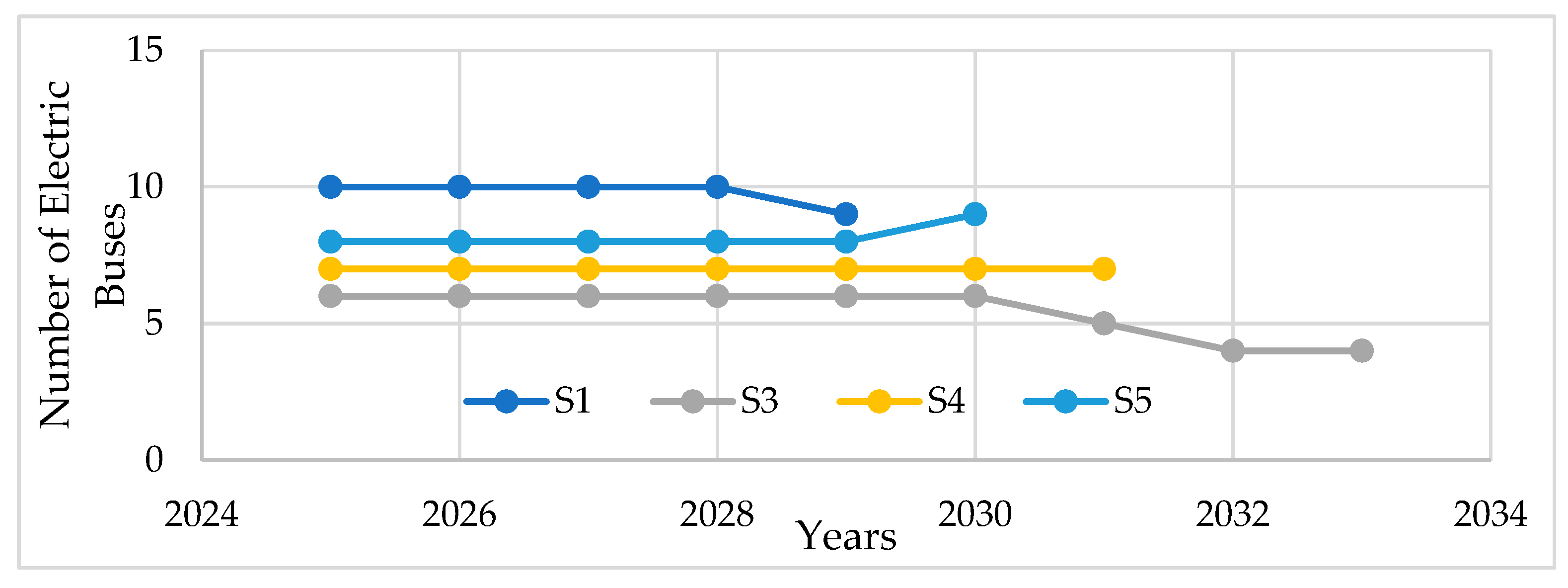

- If the priority is earliest electrification, the increased budget (Scenario 1, S1) is an effective tool, but requires a clear presentation of the higher overall infrastructure costs. In this case, the objective function has the highest value, i.e., the acceleration “costs” more, but with lower emissions and earlier social benefits.

- If the objective is the lowest value of the objective function (EUR): the increased monetization of externalities (Scenario 4, S4) argues for an earlier replacement in sensitive areas, improving the overall target value compared to the baseline.

- The increased budget (Scenario 1, S1) delays electrification to year 5, while the higher price of buses (Scenario 3) postpones it to year 9.

- Budget constraints do not allow the desired change to be achieved (Scenario 2, S2).

- Even with available funds, the Rt (supply chain risk) constraint is unacceptable (scenario 6, S6).

- EU subsidy and local co-financing (scenario 5, S5) require careful budget planning, related to both EU programs and the financial capabilities of the owner of the transport company in the settlement.

- Budgetary constraints are a critical factor—even with the lower operating costs of electric buses. Their high purchase price limits the number that can be replaced;

- Prioritizing social/environmental benefits (β > α) leads to a different replacement structure. With a preference for earlier replacement despite higher upfront costs;

- The flexibility of the model allows it to adapt to a dynamic environment—when one or more parameters change. Solver finds a new optimal solution;

- Scenario planning is a tool for sustainable management that can support policy dialogue and the justification of investment programs;

- The “What-if” analysis makes it possible to identify which factors have the greatest influence on the results. How robust the solution is to variations in real-world conditions and where investments or policy measures will have the greatest effect.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tettamanti, A.; Varga, B.; Rottenstreich, O.; Emanuel, D. On the relationship of speed limit and CO2 emissions in urban traffic. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 32, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, L.; Wägner, N.; Zaklan, A. The air quality and well-being effects of low emission zones. J. Public Econ. 2023, 227, 105014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerepicki, A.; Kozłowski, M. Application of the Bayesian inference method to synthesize urban driving cycle speed schedules using measured data. Transp. Probl. 2024, 19, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gressai, M.; Varga, B.; Tettamanti, T.; Varga, I. Investigating the impacts of urban speed limit reduction through microscopic traffic simulation. Commun. Transp. Res. 2021, 1, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.; Garnett, R.; Ferguson, M.; Kanaroglou, P. Electric buses: A review of alternative powertrains. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajunen, A.; Lipman, T. Lifecycle cost assessment and carbon dioxide emissions of diesel, natural gas, hybrid electric, fuel cell hybrid and electric transit buses. Energy 2016, 106, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buekers, J.; Van Holderbeke, M.; Bierkens, J.; Int Panis, L. Health and environmental benefits related to electric vehicle introduction in EU countries. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 33, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Xing, T.; Li, Y. Optimization of electric bus vehicle scheduling and charging strategies under Time-of-Use electricity price. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 196, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borén, S. Electric buses’ sustainability effects, noise, energy use, and costs. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 14, 956–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.S.G.; Lusby, R.M.; Larsen, J. Electric bus planning & scheduling: A review of related problems and methodologies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzolli, J.A.; Trovão, J.P.; Antunes, C.H. A review of electric bus vehicles research topics—Methods and trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, T. Recent Developments and Challenges with Electric Bus Implementation for Transit Fleets. Curr. Sustain./Renew. Energy Rep. 2025, 12, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soylu, S.; Demir, Z. Investigation of basic operating characteristics of conventional, diesel-electric and hybrid-electric city buses under urban driving conditions. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendra, M.; Pribula, D.; Skrúcaný, T.; Blažeková, O.; Stoilova, S. Battery-Assisted Trolleybuses: Effect of Battery Energy Utilization Ratio on Overall Traction Energy Consumption. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtova, I.; Sejkorova, M.; Verner, J.; Sarkan, B. Comparison of electricity and fossil fuel consumption in trolleybuses and buses. In Proceedings of the 17th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 23–25 May 2018; pp. 2079–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, S.; Jabali, O.; Mendoza, J.E.; Laporte, G. The electric bus fleet transition problem. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 109, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lo, H.K.; Xiao, F. Mixed bus fleet scheduling under range and refueling constraints. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 104, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laib, F.; Braun, A.; Rid, W. Modelling noise reductions using electric buses in urban traffic: A case study from Stuttgart, Germany. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 37, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T.H.; Farzaneh, H. Quantifying the multiple environmental, health, and economic benefits from the electrification of the Delhi public transport bus fleet, estimating a district-wise near roadway avoided PM2.5 exposure. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 116027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, S.; Jabali, O.; Laporte, G. The electric vehicle routing problem with energy consumption uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 126, 225–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.; Pradhan, R. A comprehensive review and research agenda on the adoption, transition, and procurement of electric bus technologies into public transportation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 75, 104218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, V.; Stewart, T. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: An Integrated Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. COM (2019) 640 Final. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2019/1161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 Amending Directive 2009/33/EC on the Promotion of Clean and Energy-Efficient Road Transport Vehicles. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L1161 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy—Putting European Transport on Track for the Future. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0789 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/550 of 8 March 2023 on National Support Programmes for Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning (Notified Under Document C(2023) 1524). Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L 73, 23–33. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX%3A32023H0550 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Commission Directive 2003/27/EC of 3 April 2003 on Adapting to Technical Progress Council Directive 96/96/EC as Regards the Testing of Exhaust Emissions from Motor Vehicles (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?from=ET&uri=CELEX%3A32003L0027 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Fleet Dynamics | Initial numbers of diesel and electric buses; amortization cycles; annual replacement limits |

| Budget Constraints | Annual investment and operational budgets; subsidies; unit costs of vehicles and charging infrastructure |

| Operational Costs | Energy/fuel consumption, maintenance, and infrastructure service costs |

| Emissions | Annual CO2 emissions, particulate matter (PM10), and noise levels |

| Social Indicators | Monetized health savings; public acceptance; valuation of externalities on health and environment |

| No. | Achievement | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Electrification of the fleet |

|

| 2 | Consolidation as the sole urban operator | As of 1 July 2024, the company operates all municipal bus lines:

|

| 3 | Deployment of intelligent transport systems | GPS tracking, automatic passenger counting, centralized dispatching:

|

| 4 | Increased safety | Pilot implementation of video surveillance in vehicles:

|

| 5 | Digitalization of technical maintenance | Development of digital systems for:

|

| Indicator | Diesel Buses | Electric Buses |

|---|---|---|

| Mileage, km | 60,000 | 60,000 |

| Energy price (excl. VAT), EUR/L or EUR/kWh | 1.02 | 0.13 |

| Energy consumption per 100 km, L/kWh | 48.00 | 200.00 * |

| Cost per 100 km (excl. VAT), EUR | 49.08 | 26.34 |

| Annual maintenance (TO1 + TO2), EUR | 715.81 | 485.73 |

| Total annual cost per bus, EUR | 30,166.22 | 16,290.78 |

| Parameter | Possible Scenarios | Potential Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Price of an electric bus (Ce) | Increase/decrease | Determines the number of buses that can be purchased annually |

| Annual investment budget (Bt) | Optimistic/realistic/pessimistic | Determines the intensity of fleet replacement |

| Operating costs (Oe, Od) | Reduction through technological improvements or increase due to inflation | Affects long-term cost saving |

| CO2 and PM emissions (Ed, Ee, PMd, PMe) | Change in the energy mix or environmental standards | Affects the assessment of environmental impact |

| Weights in the objective function (α, β) | Priority towards environmental goals or cost savings | Alters the replacement strategy |

| Maximum number of buses replaced (Rt) | Logistical constraints or accelerated replacement | Directly influences the pace of electrification |

| Infrastructure investments (It) | Shortage/surplus of charging stations | Affects the practical feasibility of electrification |

| Scenarios | Full Electrification (Year) | Total Purchased Electric Buses | Total Cost for Buses (EUR) | Total Costs for Electric Buses and Infrastructure (EUR) | Objective Function (EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 5 | 49 | 27,558,632 | 7,670,000 | 42,619,322.30 |

| S2 | not achieved in 10 years | ||||

| S3 | 9 | 49 | 32,569,291 | 5,115,000 | 40,466,938.21 |

| S4 | 7 | 49 | 27,558,632 | 5,115,000 | 36,582,353.27 |

| S5 | 6 | 49 | 27,558,632 | 6,134,000 | 41,379,457.49 |

| S6 | not achieved in 10 years | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pencheva, V.; Asenov, A.; Georgiev, A.; Mineva, K.; Kulev, M. An Integrated Model for the Electrification of Urban Bus Fleets in Public Transport Systems. Eng. Proc. 2026, 121, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121028

Pencheva V, Asenov A, Georgiev A, Mineva K, Kulev M. An Integrated Model for the Electrification of Urban Bus Fleets in Public Transport Systems. Engineering Proceedings. 2026; 121(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121028

Chicago/Turabian StylePencheva, Velizara, Asen Asenov, Aleksandar Georgiev, Kremena Mineva, and Mladen Kulev. 2026. "An Integrated Model for the Electrification of Urban Bus Fleets in Public Transport Systems" Engineering Proceedings 121, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121028

APA StylePencheva, V., Asenov, A., Georgiev, A., Mineva, K., & Kulev, M. (2026). An Integrated Model for the Electrification of Urban Bus Fleets in Public Transport Systems. Engineering Proceedings, 121(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121028