Influence of Impurities on the Hot Shortness of Brass Alloys †

Abstract

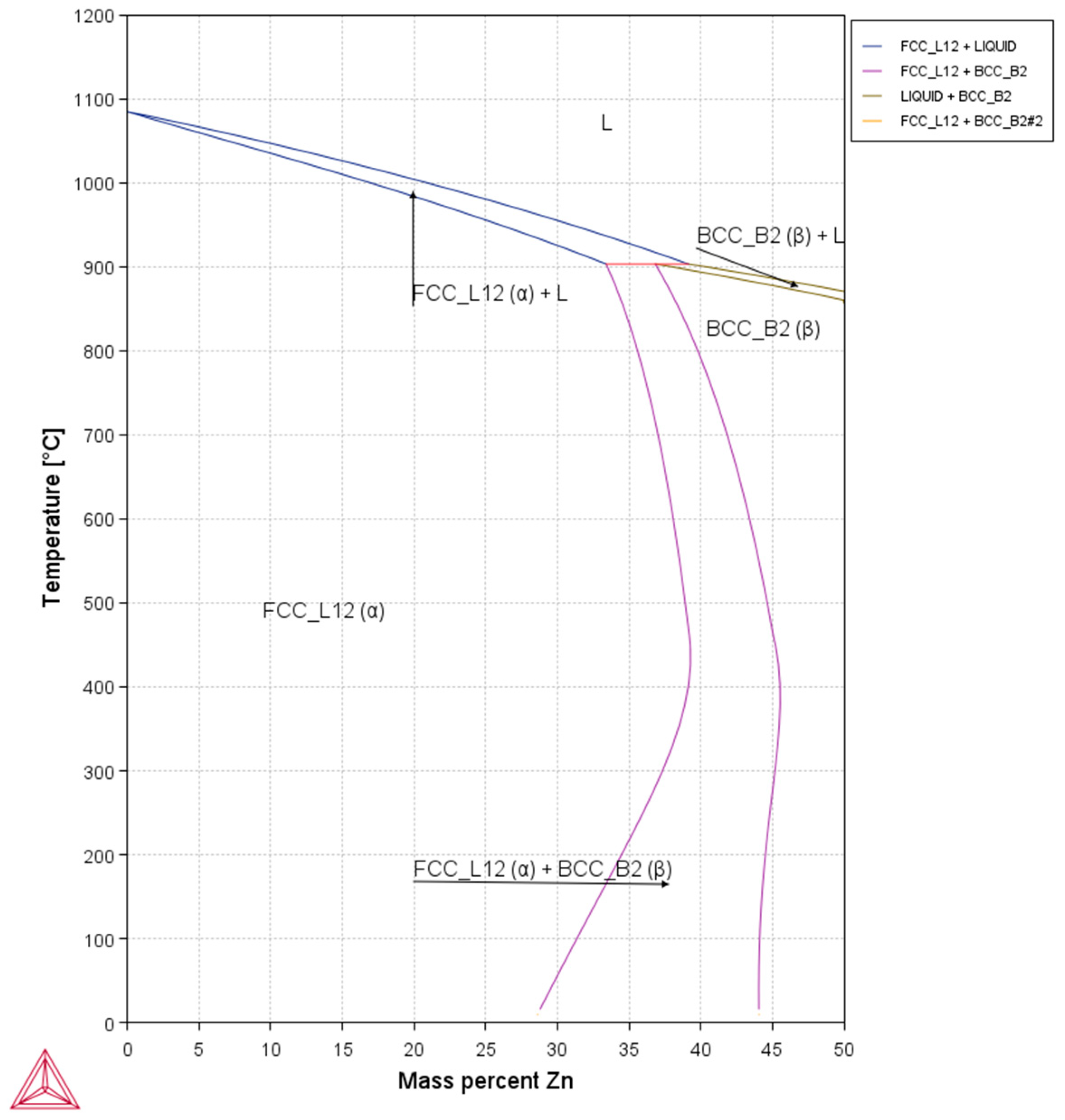

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wu, T.; Li, R.; Chai, S. Microstructure and behavior of secondary brass alloy ingots as influenced by Ti and B. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.S.; Brans, K.; Meurer, M.; Sørby, K.; Bergs, T. The effect of high-pressure cutting fluid supply on the chip breakability of lead-free brass alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 129, 4317–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobel, C.; Klocke, F.; Lung, D.; Wolf, S. Machinability Enhancement of Lead-Free Brass Alloys. Procedia CIRP 2014, 14, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.P. Failures of Structures and Components by Metal-Induced Embrittlement. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. (JFAP) 2008, 8, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannengiesser, T.; Boellinghaus, T. Hot cracking tests—An overview of present technologies and applications. Weld World 2014, 58, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Katgerman, L.; Du, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, L. Recent advances in hot tearing during casting of aluminium alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 117, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnusina, A.M.; Svyatkin, A.V. The influence of phosphorus microalloying on the structure formation of CuZn32Mn3Al2FeNi multicomponent brass. Front. Mater. Technol. 2024, 3, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndorf, S.; Markelov, A.; Guk, S.; Mandel, M.; Krüger, L.; Prahl, U. Development of a Dezincification-Free Alloy System for the Manufacturing of Brass Instruments. Metals 2024, 14, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, A.; Grasser, M.; Schillinger, W. Experimental Investigation on the Ternary Phase Diagram Cu-Sn-P. World Metall. 2012, 65, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Yunguo, L.; Korzhavyi, P.A.; Sandström, R.; Lilja, C. Impurity effects on the grain boundary cohesion in copper. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2017, 1, 070602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, R.; Lousada, C. The role of binding energies for phosphorus and sulphur at grain boundaries in copper. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 544, 152682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, D.; Begović, E.; Kostov, A.; Ekinović, S. Lead-Free Alternatives for Traditional Free Machining Brasses. In Proceedings of the 43rd International October Conference on Mining and Metallurgy, Kladovo, Serbia, 12–15 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, B.; Wang, G. Purification of Cu–Zn melt based on the migration behavior of lead and bismuth under pulsed electric current. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 396, 136577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulakis, P.; Toulfatzis, A.I.; Pantazopoulos, G.A.; Paipetis, A.S. Machinable Leaded and Eco-Friendly Brass Alloys for High Performance Manufacturing Processes: A Critical Review. Metals 2022, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinfest, R.; Paxton, A.T.; Finnis, M.W. Bismuth embrittlement of copper is an atomic size effect. Nature 2004, 432, 1008–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, J.O.; Helander, T.; Höglund, L.; Shi, P.F.; Sundman, B. Thermo-Calc & DICTRA, Computational tools for materials science. Calphad 2002, 26, 273–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 12164:2016; Copper and Copper Alloys-Rod for Free Machining Purposes. BSI Standards: London, UK, 2016.

| Element | EN12164:2016 | Utilized |

|---|---|---|

| As | - | 1.0 |

| Sn | 0.3 | 0.30 |

| P | 0.2 | |

| S | - | |

| Te | - | |

| Se | 0.02 | |

| Sb | - | |

| Cr | 0.2 | |

| Ni | 0.3 | 0.20 |

| Fe | 0.3 | 0.30 |

| Al | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Bi | 0.02 | |

| Pb | 2.5–3.5 | 3.2 |

| Zn | REM | REM |

| Co | 0.2 | |

| Ag | 0.2 | |

| Si | 0.3 | |

| Mn | - | 1.0 |

| Cd | 0.2 | |

| Cu | 57.0–59.0 | 58.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loukadakis, V.; Skepetzaki, E.; Bouzouni, M.; Papaefthymiou, S. Influence of Impurities on the Hot Shortness of Brass Alloys. Eng. Proc. 2025, 119, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119032

Loukadakis V, Skepetzaki E, Bouzouni M, Papaefthymiou S. Influence of Impurities on the Hot Shortness of Brass Alloys. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 119(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119032

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoukadakis, Vasilis, Eleni Skepetzaki, Marianthi Bouzouni, and Spyros Papaefthymiou. 2025. "Influence of Impurities on the Hot Shortness of Brass Alloys" Engineering Proceedings 119, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119032

APA StyleLoukadakis, V., Skepetzaki, E., Bouzouni, M., & Papaefthymiou, S. (2025). Influence of Impurities on the Hot Shortness of Brass Alloys. Engineering Proceedings, 119(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119032