1. Introduction

In addition to the standard EN 13906-2 [

1] for component design, a fatigue strength verification according to the FKM-guideline for general components [

2] is typically carried out. More recently, a new edition of the FKM-guideline for springs [

3], which was significantly co-developed at the Technical University of Ilmenau, has been published. However, this guideline does not contain specific design recommendations tailored to tension springs for determining permissible stresses at fatigue-critical locations.

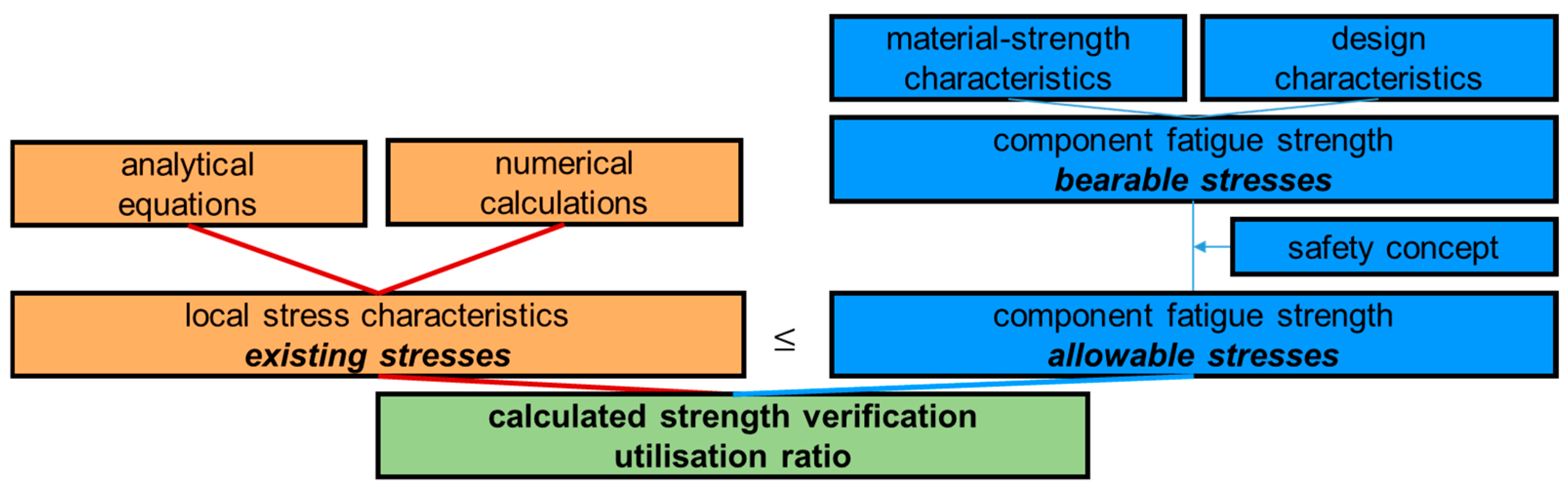

The fatigue strength verification always follows the same procedure (

Figure 1).

First, the existing stresses in the component must be determined, which is usually accomplished analytically and/or numerically. Second, the determination of the bearable stresses based on material and design parameters is required, which are then converted into allowable stresses through a safety concept. Finally, fatigue strength verification is achieved by calculating a utilization ratio (the quotient of existing to allowable stress amplitude) at each verification point. The utilization ratio must always be ≤1.

Helical tension springs exhibit specific geometric characteristics. The tensile force must be introduced into the spring body in an appropriate manner. Consequently, numerous variants of end-coil and loop designs have been established, which were also the subject of investigations in project IGF 22762 BR [

4]. The most commonly used loop geometries are the “Closed/half German loop”, the “extended German side loop” and the “English loop”. These loop forms were already investigated in project IGF 22762 BR [

4].

For the “English loop” and the “extended German side loop”, calculation methods have already been developed at Technical University of Ilmenau [

4,

5], enabling the analytical determination of existing stresses as a function of external loading in a straightforward manner.

In the case of the “half German loop” (HGL), however, determining the existing stresses is more challenging, since this involves a superposition of different stress types (bending, tension and torsional stresses).

2. Special Case “Half German Loop”

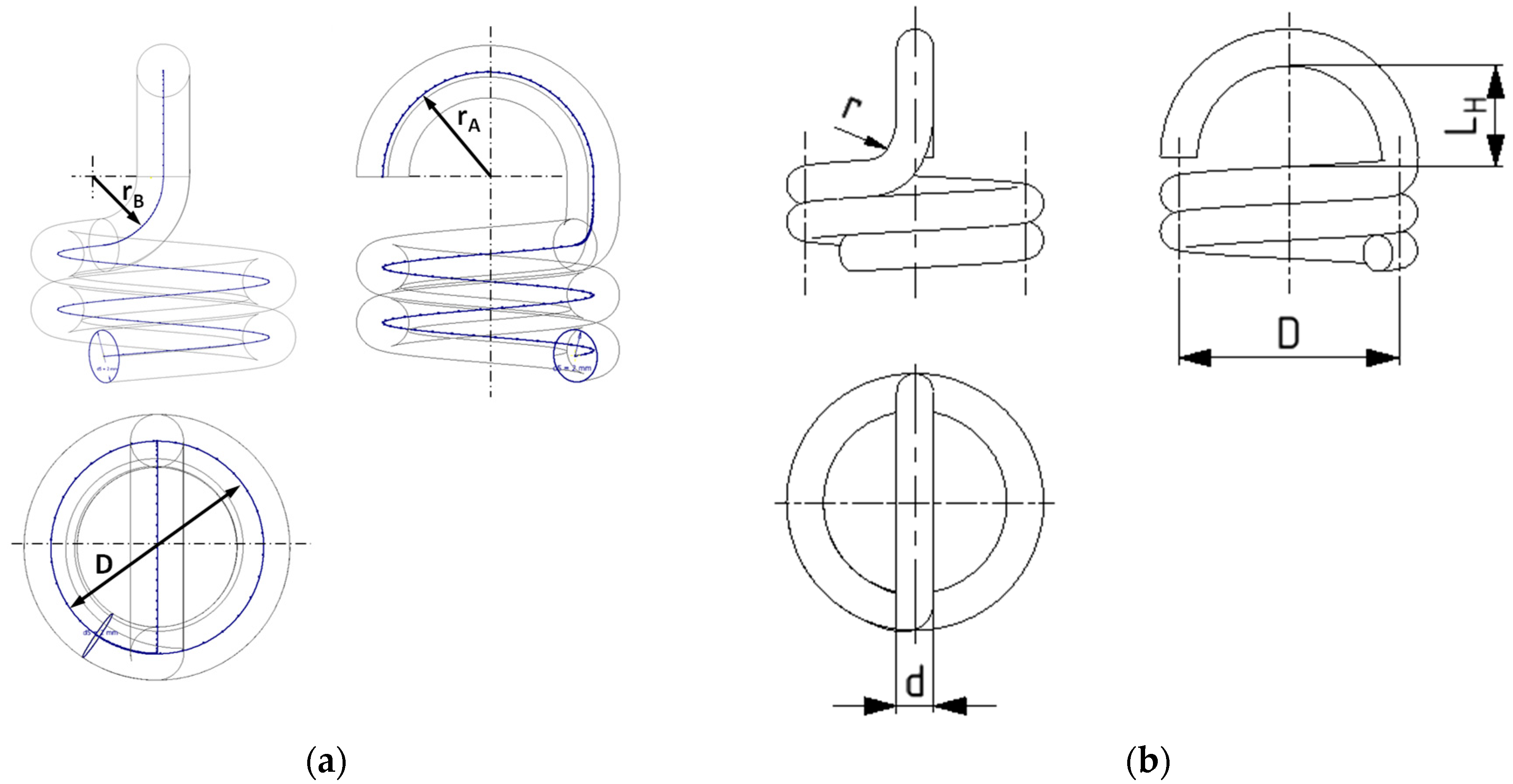

Due to its compact design, the HGL is particularly suitable for confined installation spaces and is among the most established loop forms. For the failure of tension springs with HGL, three critical areas are relevant (

Figure 2). The loop is subjected to bending and tension, and this failure-critical region is usually referred to as A in the literature. At the transition between the spring body and the loop lies region B, where the bending stress from the loop is superimposed with the torsional stress from the spring body. An exact localization of the maxima of the individual stresses or the maximum equivalent stress does not exist and strongly depends on the actual wire trajectory and its curvature. The spring body itself is subject to torsion, denoted here as region FK.

Compared to other loop forms, the HGL poses considerable stress-related challenges. On the one hand, due to the small loop height , the radius r at the loop transition (region B) is often very small, which significantly increases stresses. Furthermore, the analysis is complicated by the direct superposition of bending and torsional stresses, since regions A and B can be located very close to each other or even merge smoothly.

Although analytical approaches for determining the existing stresses were developed as part of the IGF 22762 BR [

4] project, these are partly very complex and can only be applied with significant technical and time effort. Many spring-manufacturing companies lack access to such resources. Moreover, in certain cases, the application of these analytical results would lead to extremely conservative spring designs, which is of little practical interest.

In order to determine the stresses nevertheless, numerical calculations or finite element (FE) simulations are employed. Based on the simulation results, a simplified and practicable fatigue strength verification method using a transfer factor was developed. With the help of the transfer factor, the torsional stresses in the spring body are converted into the maximum equivalent stresses in the loops, ultimately enabling a conservative spring design.

3. Methodological Approach

3.1. FE-Parameter Study

The FE simulations were based on reduced spring models with one loop and an attached coil number of

= 2, which were modeled using CAD software Autodesk Inventor Professional 2025 The required coordinates of the wire centerline were calculated in Microsoft Excel using the parameters wire diameter

, spring index

, transition radius

, and number of coils

(shown in

Figure 3).

Within the parameter study, the wire diameter was fixed at

= 2 mm, and the spring index of the spring body

was set equal to the spring index of the loop

. In total, six spring indices were simulated, each with six different loop heights and transition radii.

Table 1 shows the factors with the corresponding levels.

The spring models generated in this manner were saved as step files and subsequently imported into the simulation software Ansys (version 2024 R1). The parameter variations resulted in a total of 108 spring models.

In the simulations, the springs were subjected to an external load applied concentrically to the spring axis at the loop in the positive z-direction, thereby stretching the spring. To ensure comparability of simulation results for different spring indices of the spring body, the forces were selected such that all simulated springs generated the same nominal torsional stress in the spring body. In this particular case, the stress amounted to approximately 684 MPa. Each spring was simulated and analyzed with respect to the equivalent stresses (von Mises), particularly in the loop (region A) and the loop transition (region B).

To translate the simulation results into practical applicability, the following section presents a pragmatic approach that enables a simplified fatigue strength verification in accordance with the FKM-guideline.

3.2. Pragmatic Determination of Existing Stresses

For all spring variants within the FE parameter study, the respective global maximum of the equivalent stress was first determined by means of FE simulation. Detailed evaluations of the simulation results revealed that this maximum, depending on the spring geometry, occurs in region B, B′, or A. Consequently, in principle, verification would be required for all three regions, which would complicate the strength verification. To circumvent this issue, for each simulated spring geometry the ratio of the respective maximum equivalent stress (in region B or A) to the nominal equivalent stress in the spring body

was calculated. This stress ratio hereinafter referred to as the transfer factor

.

The nominal equivalent stress in the spring body can be calculated using Equation (2). Deviations between FE simulation and analytical calculation in the region of the spring body are negligibly small.

For the loop transition B, knowledge of the actual minimum transition radius of the real spring is necessary. However, the curvature radius of the spline

cannot be determined experimentally. Therefore, a projection of the radius

onto the y-z plane of the spring model was first performed (see

Figure 4).

Through this projection, the transition radius

(lateral radius of the wire centerline) was determined for each sectional plane (angle

) using Autodesk Inventor. Subsequently, the minimum value of

was identified, as the maximum equivalent stress is expected to occur at this location. Since, in practice, only the lateral radius of the wire’s inner side r can be measured, half of the wire diameter had to be added in order to obtain the value of

:

The lateral curvature ratio

is then derived as follows:

Subsequently, the transmission factor

according to Equation (1) was calculated for each simulated spring and plotted against the respective lateral curvature ratio

. This resulted in a family of curves for each spring index w as a function of

. As the curve progressions for

with different loop heights for each spring index differed only marginally, a simplified approach was adopted by estimating the “worst case” for each spring index. For this purpose, only the curve progression with the highest transmission factors was selected. Following this procedure, a total of six curve progressions were obtained, as shown in

Figure 5.

Up to a curvature ratio of

= 4, the curves exhibit quadratic behavior. For a curvature ratio

≥ 4, the respective curve passes into a horizontal line. This horizontal asymptote depends on the spring index w and corresponds to the stress ratio

, derived from the maximum equivalent stress

and the equivalent stress in region A

(loop):

Reason for considering : When forming the transfer factor , only equivalent stresses occurring in the loop transition B are taken into account. However, for certain spring geometries, the global stress maximum may not occur in region B but rather in region A. If factor were not considered, there would be a risk of conducting the strength verification in region B, while the global stress maximum—and thus the failure-critical location—actually lies in region A.

With the aid of the diagram, the transfer factors for various tension springs with HGL can be determined. For this, only knowledge of the spring index w and the curvature ratio in the loop transition is necessary.

4. Application of the Results

The application of the procedure described above will be explained in more detail using a calculation example. The existing stress amplitude and the allowable stress amplitude are required for the fatigue strength verification. We begin by determining the existing stresses.

As an example, a tension spring with a half German loop, wire diameter

= 2 mm, and spring ratio

= 4 is considered. Furthermore, a transition radius of

= 3 mm and a loop height of

= 0.55 ×

are assumed. The smallest spring force

present during the oscillation cycle is 80 N, and the largest spring force

is 140 N. Using the specified values, the first step is to calculate the nominal shear stresses in the spring body as a result of

and

:

This is followed by the determination of the lateral curvature ratio to:

With the aid of the transfer factor

, the nominal shear stresses are converted into a comparative stress in the next step. The diagram in

Figure 5 is used to determine

. For the assumed spring with

= 3 and w = 4, this results in a stress transfer factor of

.

The stress corresponds to the existing minimum stress , while the stress is equivalent to the existing maximum stress .

The maximum and minimum stresses can then be used to calculate the mean stress

and the stress amplitude

:

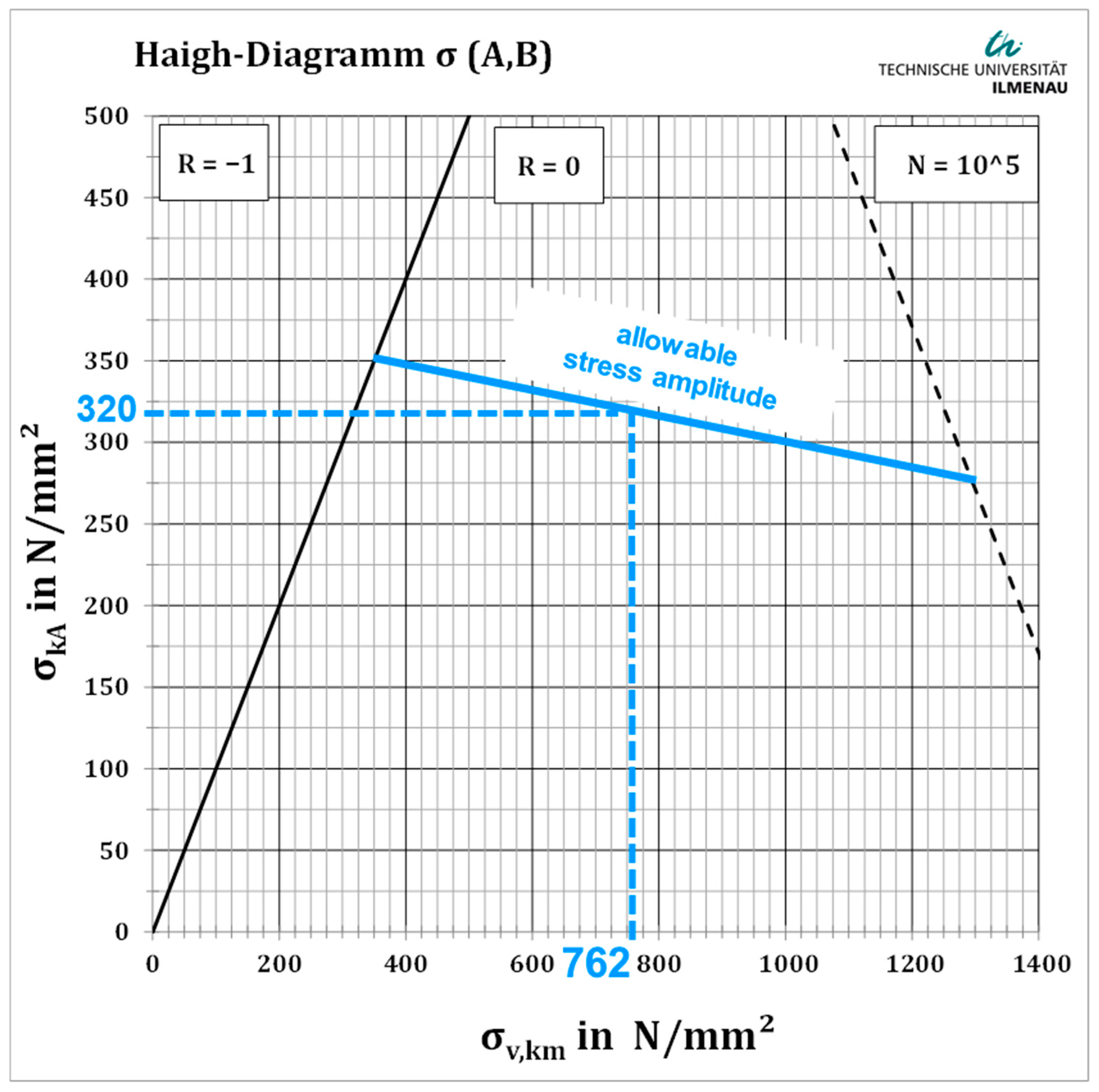

To determine the allowable stresses, the new fatigue strength diagrams (Goodman, Haigh) for tension springs based on the FKM guideline for springs and spring elements are used. With the help of the guideline, locally tolerable stress amplitudes for a mean stress are calculated, taking various factors (roughness, surface, dimensions, etc.) into account. A safety concept converts the bearable stresses into allowable stresses. To create the strength diagrams, a broad-based test program was implemented at the research center, which enabled the determination of experimentally bearable stresses in cyclic tests.

The case study considers a heat-treated, non-shot-peened tension spring. The spring material is assumed to be patented drawn wire with a tensile strength of

= 2150 MPa. The following

Figure 6 shows the corresponding Haigh diagram, calculated according to the FKM guideline for springs [

3] as part of the IGF 22762 BR project [

4] for normal stress verification (load cycle number

, mean roughness, heat treatment 200 °C, failure probability 0.1%).

Based on the previously calculated existing mean stress (; see Equation (13)), the allowable stress amplitude can be read directly from the Haigh-diagram. In the example shown, this is approximately 320 MPa.

For the strength verification, the utilization factor

is finally formed as the ratio of the existing and allowable stress amplitude:

The utilization factor in the loop transition is proven to be less than one. Thus, the strength verification for this spring has been successfully completed.

5. Summary and Conclusions

Based on the new FKM guideline for springs and spring elements, the calculation procedure shown can be used to determine the degree of utilization at the individual verification points of a tension spring with a half German loop. The scientific results are presented in a practical manner and can be easily applied in an industrial environment.

When using this method, only a strength verification for the loop needs to be done (in addition to the verification in the spring body). It is irrelevant in which area of the spring (B’, B, or A) the global stress maximum lies. The conversion of the nominal shear stress in the spring body into an equivalent stress allows a normal stress verification, which also favors the use of equivalent stresses from FE simulations. The utilization factors can be determined for both static and cyclic verification.

In general, this is an estimation that leads to a higher equivalent stress compared to the real spring, resulting in a higher degree of utilization of the spring being calculated. The design is therefore conservative.

In principle, the approach presented here can already be used to perform a simplified fatigue strength verification in accordance with the FKM guideline for springs under normal stresses.

One aspect that has not yet been taken into account is the residual stresses present in the fracture-critical areas. However, these can have a significant effect on the permissible stresses, which can lead to a significant influence on the calculated utilization factor in the context of fatigue strength verification. Knowledge of the magnitude and direction of residual stresses is therefore essential for safe and load-optimized spring design. This is currently being worked on in project IGF 22762 BR.