Relationship of the Security Awareness and the Value Chain †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Value Chain and Its Role in the Business

2.2. The Importance of Digitalization for Businesses

2.3. The Importance and Challenges of Security Awareness

3. Methodology

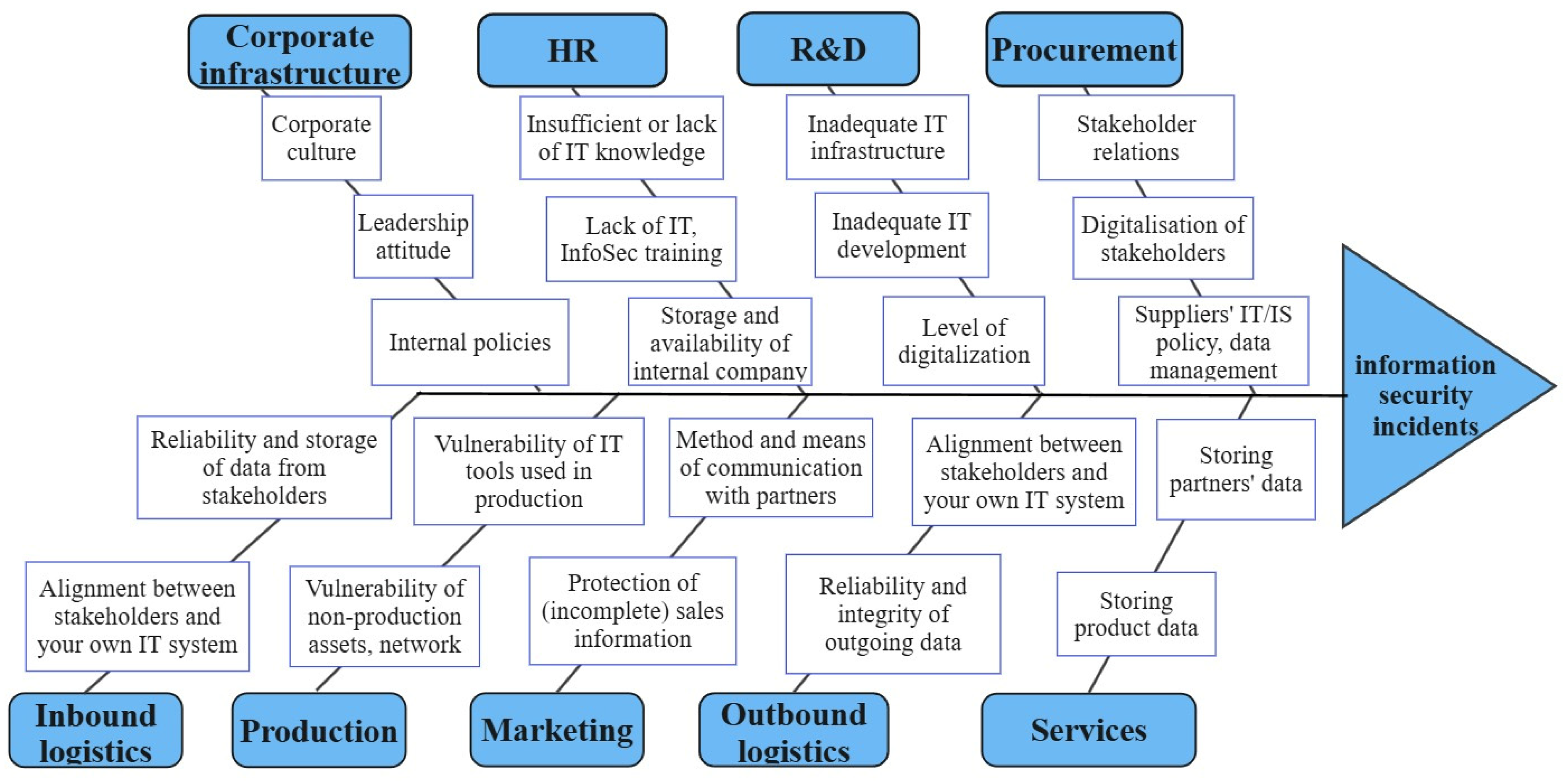

- Defining the problem—it is essential to define the problem as specifically as possible, and then we looked for answers to questions starting with “Why.”

- Subsequently, we added the individual elements of the value chain as the main causal categories.

- Brainstorming about causes: gathering the reasons for each main category from the literature and practical examples and adding them to the diagram. Individual reasons were merged or assigned to several categories.

- Search for additional reasons—As each reason was added to the chart, we looked for additional possible causes, checking to see if we had missed any potential additional causes.

4. Result

IS and the Value Chain

5. Conclusions

- Management and upper levels of management must demonstrate exemplary behavior, which includes the creation of clear and enforceable rules with the involvement of employees.

- Continuous IS education, IS awareness, and evaluation of the company as a whole, covering the entire company.

- Regular consultations should be held with existing suppliers and partners on a monthly basis regarding common IS solutions and situational awareness.

- The regular assessment of new and existing partners should also be carried out from an IT aspect, which includes the compatibility and vulnerability of the systems used, as well as the corporate culture from the IS side and its support.

- Harmonization and continuous review of existing IS regulations and rules.

- Close cooperation of universities/educational institutions from a research point of view as well and incorporating research results and their lessons into training and cooperation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szász, L.; Demeter, K.; Rácz, B.-G.; Losonci, D. Industry 4.0: A Review and Analysis of Contingency and Performance Effects. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 32, 667–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi-Yazdi, E.; Couzon, P.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Ouazene, Y.; Yalaoui, F. Industry 4.0: Revolution or Evolution? Am. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 10, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoryadkina, E.B.; Mezentseva, E.; Animitsa, E.G. Advantages and Barriers of Industry 4.0 Concepts Implementation in Small and Medium Industrial Enterprises. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 93, 01007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.; Kruschwitz, N.; Bonnet, D.; Welch, M. Embracing Digital Technology: A New Strategic Imperative. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2014, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wißotzki, M.; Sandkuhl, K.; Wichmann, J. Digital Innovation and Transformation: Approach and Experiences. In Architecting the Digital Transformation; Zimmermann, A., Schmidt, R., Jain, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.U.; Murray, J. Understanding the Connect between Digitalisation, Sustainability and Performance of an Organisation. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2019, 17, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikovska–Georgievska, S. E-Commerce—Challenge for Sustainable Development of Companies. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 4, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Va, K.P. Reinventing the Art of Marketing in the Light of Digitalization and Neuroimaging. In Amity Global Business Review; Amity University Press: Noida, India, 2015; pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Csedő, Z.; Zavarkó, M.; Sára, Z. Is Digitalization an Innovation? Lessons from Digital Transformation and Innovation Management at a Financial Services Provider (Innováció-e a Digitalizáció? A Digitális Transzformáció és az Innovációmenedzsment Tanulságai Egy Pénzügyi Szolgáltatónál). Vezetéstudomány/Budap. Manag. Rev. 2019, 50, 88–101. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichosz, M.; Wallenburg, C.M.; Knemeyer, A.M. Digital Transformation at Logistics Service Providers: Barriers, Success Factors and Leading Practices. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2020, 31, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.; Melville, N.P. Digital Innovation: A Review and Synthesis. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 29, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M.A. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Pedersen, C.L. Digitization Capability and the Digitalization of Business Models in Business-to-Business Firms: Past, Present, and Future. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 86, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, K.; Losonci, D.; Szász, L.; Rácz, B.-G. Analysis of Industry 4.0 Practices in Hungarian Manufacturing Units—Technology, Strategy, Organization (Magyarországi Gyártóegységek Ipar 4.0 Gyakorlatának Elemzése—Technológia, Stratégia, Szervezet). Vezetéstudomány/Budap. Manag. Rev. 2020, 51, 2–14. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vörösmarty, G.; Tátrai, T.; Havasi, Z. The Role of Purchasing in the Hungarian Small and Medium Enterprises (A Beszerzés Helye és Szerepe a Magyarországi Kis- és Középvállalatoknál). Vezetéstudomány/Budap. Manag. Rev. 2010, 41, 36–44. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikán, A.; Demeter, K. Management of Value-Creating Processes—Production, Service, Logistics (Az Értékteremtő Folyamatok Menedzsmentje—Termelés, Szolgáltatás, Logisztika), 5th ed.; Aula Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2006. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Ricciotti, F. From Value Chain to Value Network: A Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2019, 70, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, S. Applying Assessment and Analysis Techniques to Businesses (Állapotfelmérési és Elemzési Technikák Alkalmazása Vállalkozásoknál); Kaposvári Egyetem—Pannon Egyetem—Szegedi Gabonakutató Nonprofit Kft: Kaposvár, Hungary, 2014. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Dragolea, L.-L.; Butnaru, G.I.; Kot, S.; Zamfir, C.G.; Nuţă, A.-C.; Nuţă, F.-M.; Cristea, D.S.; Ştefănică, M. Determining factors in shaping the sustainable behavior of the generation Z consumer. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1096183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Bai, A.; Karmazin, G.; Balogh, P.; Popp, J. The Role Played by Trust and Its Effect on the Competiveness of Logistics Service Providers in Hungary. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tick, A.; Reka, S.; Judit, K.-D. The effect of digitalisation on sustainable operation of SMEs–the case of Hungary. In Possibilities and barriers for Industry 4.0 implementation in SMEs in V4 countries and Serbia; Mihajlović, I., Ed.; University of Belgrade, Technical Faculty in bor, EMD: Bor, Serbia, 2022; pp. 121–150. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.D.; Xu, E.L.; Li, L. Industry 4.0: State of the Art and Future Trends. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2941–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reischauer, G. Industry 4.0 as Policy-Driven Discourse to Institutionalize Innovation Systems in Manufacturing. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 132, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeuf, A.; Pellerin, R.; Lamouri, S.; Tamayo-Giraldo, S.; Barbaray, R. The Industrial Management of SMEs in the Era of Industry 4.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 1118–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.Y.; Martinho, B.; Silva, R.; Lima, R.M.; Costa, E.; Pimentel, C. A Big Data Analytics Architecture for Industry 4.0. In Innovation in Engineering; Azevedo, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; Park, J.H.; Son, J.Y.; Kim, B.H.; Do Noh, S. Smart Manufacturing: Past Research, Present Findings, and Future Directions. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2016, 3, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, G.; Potente, T.; Wesch-Potente, C.; Weber, A.R.; Prote, J.P. Collaboration Mechanism to Increase Productivity in the Context of Industrie 4.0. In Procedia CIRP, Proceedings of 2nd CIRP Robust Manufacturing Conference (RoMac 2014), Bremen, Germany, 7–9 July 2014; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 19, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Götz, M.; Jankowska, B. Clusters and Industry 4.0—Do They Fit Together? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1534–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bai, T. How Digitalization Affects the Effectiveness of Turnaround Actions for Firms in Decline. Long Range Plann. 2021, 54, 102140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, L.; Yi, J.; Mao, J.; Liao, J. Ecosystem-Specific Advantages in International Digital Commerce. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 1448–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, P.J.; De Meyer, A. Ecosystem Advantage: How to Successfully Harness the Power of Partners. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2012, 55, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Schniederjans, D.G.; Schniederjans, M. Establishing the Use of Cloud Computing in Supply Chain Management. Oper. Manag. Res. 2017, 10, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, A.; Ulaga, W.; Frow, P.; Payne, A. Conceptualizing and Communicating Value in Business Markets: From Value in Exchange to Value in Use. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 69, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, T.V.; Grenier, J.H.; Layman, D. Accounting and Cybersecurity Risk Management. Curr. Issues Audit. 2019, 13, C1–C9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankard, C. What the GDPR Means for Businesses. Netw. Secur. 2016, 2016, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwitter, A. Big Data Ethics. Big Data Soc. 2014, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital Innovation and International Business. Innovation 2020, 24, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskás, E. Industry 4.0 Solutions for Implementing Logistics Networks Based on the Physical Internet (Ipar 4.0 Megoldások a Fizikai Interneten Alapuló Logisztikai Hálózatok Megvalósításához). Ph.D. Thesis, Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem, Budapest, Hungary, 2021. (In Hungarian). [Google Scholar]

- Frank, M.L.; Grenier, J.H.; Pyzoha, J.S. How Disclosing a Prior Cyberattack Influences the Efficacy of Cybersecurity Risk Management Reporting and Independent Assurance. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 33, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Kannan, K.N.; Ulmer, J.R. The Association between the Disclosure and the Realization of Information Security Risk Factors. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, E.; Levi, S.; Livne, T. Do Firms Underreport Information on Cyber-Attacks? Evidence from Capital Markets. Rev. Account. Stud. 2018, 2, 1177–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. Median Time Period Between Intrusion, Detection, and Containment of Industrial Cyber Attacks Worldwide from 2014 to 2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/221406/time-between-initial-compromise-and-discovery-of-larger-organizations/ (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Blumira. State of Detection and Response Report. Available online: https://www.blumira.com/whitepaper/state-of-detection-and-response/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Masuch, K.; Greve, M.; Trang, S.; Kolbe, L.M. Apologize or Justify? Examining the Impact of Data Breach Response Actions on Stock Value of Affected Companies. Comput. Secur. 2022, 112, 102502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; He, Y.; Maglaras, L.; Janicke, H. Heart-Is: A Novel Technique for Evaluating Human Error-Related Information Security Incidents. Comput. Secur. 2019, 80, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.; Calic, D.; Pattinson, M.; Butavicius, M.; McCormac, A.; Zwaans, T. The Human Aspects of Information Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q): Two Further Validation Studies. Comput. Secur. 2017, 66, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waly, N.; Tassabehji, R.; Kamala, M. Improving Organisational Information Security Management: The Impact of Training and Awareness. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 14th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communication & 9th International Conference on Embedded Software and Systems, Liverpool, UK, 24–26 June 2012; pp. 1270–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, S.; Carayon, P.; Clem, J. Human and Organizational Factors in Computer and Information Security: Pathways to Vulnerabilities. Comput. Secur. 2009, 28, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chatterjee, K. Cloud Security Issues and Challenges: A Survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 79, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguliyev, R.; Imamverdiyev, Y.; Sukhostat, L. Cyber-Physical Systems and Their Security Issues. Comput. Ind. 2018, 100, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, L.; Muheidat, F.; Tawalbeh, M.; Quwaider, M. IoT Privacy and Security: Challenges and Solutions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, L.Y.; Lang, M.; Gathegi, J.; Tygar, D.J. Organisational Culture, Procedural Countermeasures, and Employee Security Behaviour. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2017, 25, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsohou, A.; Karyda, M.; Kokolakis, S. Analyzing the Role of Cognitive and Cultural Biases in the Internalization of Information Security Policies: Recommendations for Information Security Awareness Programs. Comput. Secur. 2015, 52, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.F.; Dominic, P.D.D.; Ali, S.E.; Rehman, M.; Sohail, A. Information Security Behavior and Information Security Policy Compliance: A Systematic Literature Review for Identifying the Transformation Process from Noncompliance to Compliance. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgurcu, B.; Cavusoglu, H.; Benbasat, I. Information Security Policy Compliance: An Empirical Study of Rationality-Based Beliefs and Information Security Awareness. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 523–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, J.; Das, A.K.; Kumar, N. Government Regulations in Cyber Security: Framework, Standards and Recommendations. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 92, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K. Introduction to Quality Control; 3A Corporation: Tokyo, Japan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, S. Internet of Things: Underlying Technologies, Interoperability, and Threats to Privacy and Security. Berkeley Technol. Law J. 2016, 31, 997–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Seliem, M.; Elgazzar, K.; Khalil, K. Towards Privacy Preserving IoT Environments: A Survey. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, T.; Cho, J.; Han, K.; Choi, H. Toward Advanced Mobile Cloud Computing for the Internet of Things: Current Issues and Future Direction. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2014, 19, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Pasquier, T.; Bacon, J.; Ko, H.; Eyers, D. Twenty Security Considerations for Cloud-Supported Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.; Vilela, J.P. Privacy-Preserving Data Mining: Methods, Metrics, and Applications. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 10562–10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobb, T.; Turnbull, B.; Moustafa, N. Supply Chain 4.0: A Survey of Cyber Security Challenges, Solutions and Future Directions. Electronics 2020, 9, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuth, A.; Yussof, S.; Abu Baker, A.; Ali, N. A Systematic Literature Review: Information Security Culture. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 16–17 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.C.; Romero, F. A Review of the Meanings and the Implications of the Industry 4.0 Concept. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 13, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Vulnerability | Vulnerability Cause | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Human factor | Error, inattention | Evans et al. [47], Parsons et al. [48] |

| Lack of training | Waly et al. [49] | |

| Low IS knowledge and awareness. | Parsons, Calic, Pattinson, Butavicius, McCormac and Zwaans [48] | |

| Technology | Inadequate IT settings, low level of IT infrastructure/protection | Kraemer et al. [50], Singh and Chatterjee [51], Alguliyev et al. [52] |

| Irregular updates | Tawalbeh et al. [53] | |

| Leadership, culture | Lack of management/management support, inadequate corporate culture | Connolly et al. [54], Tsohou et al. [55] |

| Directive | No or inadequate policies or regulations | Ali et al. [56], Bulgurcu et al. [57] |

| External factors | Rules and regulations | Srinivas et al. [58] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bak, G.; Reicher, R. Relationship of the Security Awareness and the Value Chain. Eng. Proc. 2025, 113, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113057

Bak G, Reicher R. Relationship of the Security Awareness and the Value Chain. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 113(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113057

Chicago/Turabian StyleBak, Gerda, and Regina Reicher. 2025. "Relationship of the Security Awareness and the Value Chain" Engineering Proceedings 113, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113057

APA StyleBak, G., & Reicher, R. (2025). Relationship of the Security Awareness and the Value Chain. Engineering Proceedings, 113(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113057