Abstract

This paper explores how Smart Urban Governance, Smart Knowledge Management (Smart KM), and participatory digital tools can reshape cultural heritage rehabilitation in Morocco. Using a qualitative, multi-method approach including comparative case studies, document analysis, and thematic synthesis, it examines the institutional, technological and civic forces at play. While Morocco shows strong political will, governance remains fragmented, citizen participation low, and Smart KM underdeveloped. By drawing lessons from Spain and Indonesia, the study highlights transferable innovations in digital storytelling and participatory governance. It concludes with a roadmap for Morocco emphasizing institutional reform, Smart KM investment, and inclusive, digital engagement strategies.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage matters more than ever in how cities evolve, particularly in fast-changing contexts like those across the global south. Heritage is no longer just about monuments and memory, it is also something that shapes local economies, fosters tourism, and brings people together.

Morocco is a rich case in point. With centuries of layered history and architectural treasures, the country has made heritage a core focus. In recent years, national programs and royal directives have targeted places like Fez, Rabat, Essaouira, and Taza for restoration. These efforts have aimed to revive traditions, attract visitors, and breathe new life into historic neighborhoods. That said, if you look beyond the visible results, deeper issues emerge. Many of these projects, while ambitious, suffer from fragmented management, poor coordination between agencies, and top-down planning. Citizens, arguably those most connected to these sites, are rarely involved in shaping what happens [1,2].

In parallel, the global conversation about smart cities is opening new possibilities. In places like Spain or Indonesia, digital tools like participatory mapping, storytelling apps, or heritage databases are helping communities document and shape their own histories. Saudi Arabia too has made big moves toward digitizing and democratizing access to cultural memory. What these cases show is that technology, when used well, is not just about efficiency. It also creates new ways for people to connect with their heritage and participate in how it is managed [3,4].

In Morocco, though, this kind of smart participatory approach is still more the exception than the rule. National strategies do talk about digital transformation, but when it comes to cultural heritage, most of the innovations are isolated. They are often tied to one city, one ministry, or even just one project. There is little in the way of shared platforms or institutional memory. And when it comes to Smart KM tools that could collect, organize, and share heritage-related information and smart cities components, it is fair to say that Morocco is still in the early stages.

This paper sets out to understand what is missing and how to fix it. The raised questions include the following: How could a smarter, more open, and more connected form of heritage governance work in Morocco? How can knowledge, digital tools, and citizen voices be brought into the equation not just as add-ons, but as central components of preservation?

To address these inquiries, we examine case studies from both Morocco and international contexts, evaluating successful strategies as well as areas for improvement, and identifying adaptable lessons. The goal is to propose a new way of thinking about heritage, not as something to protect in isolation, but as something living and shared.

The research is guided by three key questions: How can smart urban governance frameworks contribute to more sustainable restoration of Moroccan cultural heritage? What function can Smart KM and digital tools play in making preservation more effective and inclusive? And finally, how involved are Moroccan citizens today and how much more could they be involved if better systems were in place?

This article unfolds in six sections. First, we provide a conceptual background. The second section lays out our methodology, using case studies, document review, and visual synthesis. In the third, we present key findings. Section four puts those findings into dialog with international examples and proposes the Triple-I Framework as a tool to rethink governance. Finally, we conclude with recommendations for bridging the gap between intention and impact.

2. Literature Review

Over the last decade, the relationship between cultural heritage governance and smart city innovation has drawn growing interest among researchers across disciplines. As cities face mounting pressures from urban growth, digital transformation, and identity fragmentation, the question of how to preserve and govern cultural memory in both physical and social forms has become more urgent than ever.

In this literature review, this paper focuses on four key domains that have come to define this evolving conversation: heritage governance, Smart KM, digital tools in preservation practice, and participatory frameworks.

2.1. Clarifying the Core Concepts

Cultural heritage governance refers to the institutional systems, legal frameworks, and actors involved in managing heritage assets ranging from historical buildings and sites to traditions, crafts, and oral history. This can involve state-led initiatives, local policies, or even informal and community-based efforts. In recent years, both researchers and global institutions have emphasized the need to align heritage governance with urban planning and sustainable development goals [5,6].

Smart Urban Governance adds a technological layer to that discussion. It is essentially about using data, digital tools, and inter-connected systems to enhance how cities are managed. When it comes to heritage, smart governance can mean anything from improved documentation platforms to transparent and participatory planning tools. What matters most here is not just the tech itself, but how it is embedded in institutional processes and made accessible to various stakeholders [3,7].

Smart KM is slightly newer in the heritage field and remains underdeveloped in many countries. It refers to how knowledge like architectural plans, restoration logs, and oral tradition is collected, structured, stored, and shared. The aim is not simply to create databases, but to ensure knowledge can travel between generations, across institutions, and even across borders. In theory, this seems obvious, but in practice, it is rarely systematic [4,5].

The concept of participatory heritage represents a movement away from decisions being made solely by experts. This framework insists that communities and not just professionals have a say in how heritage is interpreted, used, and transferred. Whether through mapping, storytelling, digital archives or gamified platforms, the participatory models aim to make heritage a lived, evolving space, rather than a frozen legacy [8,9].

2.2. Governance in Transition

Heritage governance, especially in post-colonial or post-imperial contexts, has been rooted in preservationist models. Morocco is no exception. Most national frameworks emphasize protecting physical structures, listing monuments and enforcing conservation guidelines. While this approach remains important, it does not always account for social or urban dynamics.

The recent literature suggests a need for more flexible, integrated strategies. For example, Belyazid et al. [1] highlight how lack of coordination and urban planning in Fez led to unintended gentrification and loss of cultural authenticity. Similarly, Jaouad and Chouitar [2] describe how Taza’s heritage efforts suffer from fragmented governance across municipal and regional actors. At the same time, cities like Barcelona offer alternative models where participation, adaptability, and horizontal governance have improved heritage outcomes [3].

2.3. Smart KM

Smart KM remains something of a blind spot in much of the heritage literature, especially in MENA and African contexts. While most heritage institutions claim to collect and archive, the actual systems are often outdated and poorly maintained or siloed. Morocco, for instance, lacks centralized platforms where data from different cities or ministries can be shared.

International examples, however, show what is possible. Indonesia’s Borobudur project has digitized vast archives while engaging communities through participatory tools. Saudi Arabia’s national Smart KM strategy has enabled better coordination across heritage sectors and built digital memory infrastructure that others can take inspiration from [4,5].

2.4. Digital Tools

Digital heritage tools are often seen as neutral or purely technical, but they carry deeper implications. GIS, 3D scanning, VR/AR, and HBIM are not just about recording. They shape what is seen and what is prioritized and who gets to engage with heritage.

In Europe and East Asia, cities have used these tools to open heritage interpretation to the public. Morocco has started to follow this trend. Rabat’s GIS-based mapping initiative is one example [6], but it is still in its early days. What is missing is not the tools themselves but a framework to institutionalize their use and link them with public engagement strategies. Otherwise, they risk becoming isolated pilots with limited long-term value.

2.5. Participation

The final strand, participation, is both promising and frustrating. Almost every policy document today references the importance of engaging citizens. But in practice, participation often stops at consultation sessions or scripted workshops.

By contrast, places like Slovakia and Sicily have experimented with gamification and digital storytelling to make heritage emotionally meaningful [8,9]. In Ecuador and Indonesia, heritage workshops are part of longer processes that build community capacity and ownership over time [4]. Morocco has the cultural depth and civic interest but lacks the long-term platforms and frameworks to support participatory heritage on a wider scale.

3. Materials and Methods

This research adopts a multi-method qualitative approach. It draws from comparative case study analysis, official policy document review, tool and technology mapping, and thematic synthesis of peer-reviewed literature. This methodological structure was chosen both to address the guiding research questions and to compensate for fieldwork constraints such as the inability to conduct interviews or surveys due to time limitations.

To begin, a comparative case study analysis was conducted focusing on four Moroccan heritage projects and four international initiatives. The Moroccan cases include the Fez Medina Rehabilitation Program (2020–2024), which focuses on restoration and inclusive tourism; the heritage governance framework of Taza city, known for its complex actor landscape; the GIS-based heritage inventory initiatives of Chellah; and the Oudayas in Rabat.

Internationally, the cases analyzed include Barcelona’s participatory governance model and Indonesia’s participatory 3D digitization initiatives. This comparative lens allowed for the identification of both transferable best practices and context-specific challenges in smart urban governance, participatory engagement, and Smart KM and smart cities components.

In parallel, a structured analysis of official policy documents and institutional reports was conducted to contextualize these case studies. The documents reviewed include the OECD’s 2025 National Urban Policy Review for Morocco, several UNESCO State of Conservation Reports on Fez and Rabat, and national strategic plans from the Ministry of Urban Planning and Cultural Affairs. These documents were thematically coded with a focus on four key dimensions: governance structure and actor coordination, the presence or absence of Smart KM systems, mechanisms for citizen participation, and the degree of digital tool integration into urban planning processes.

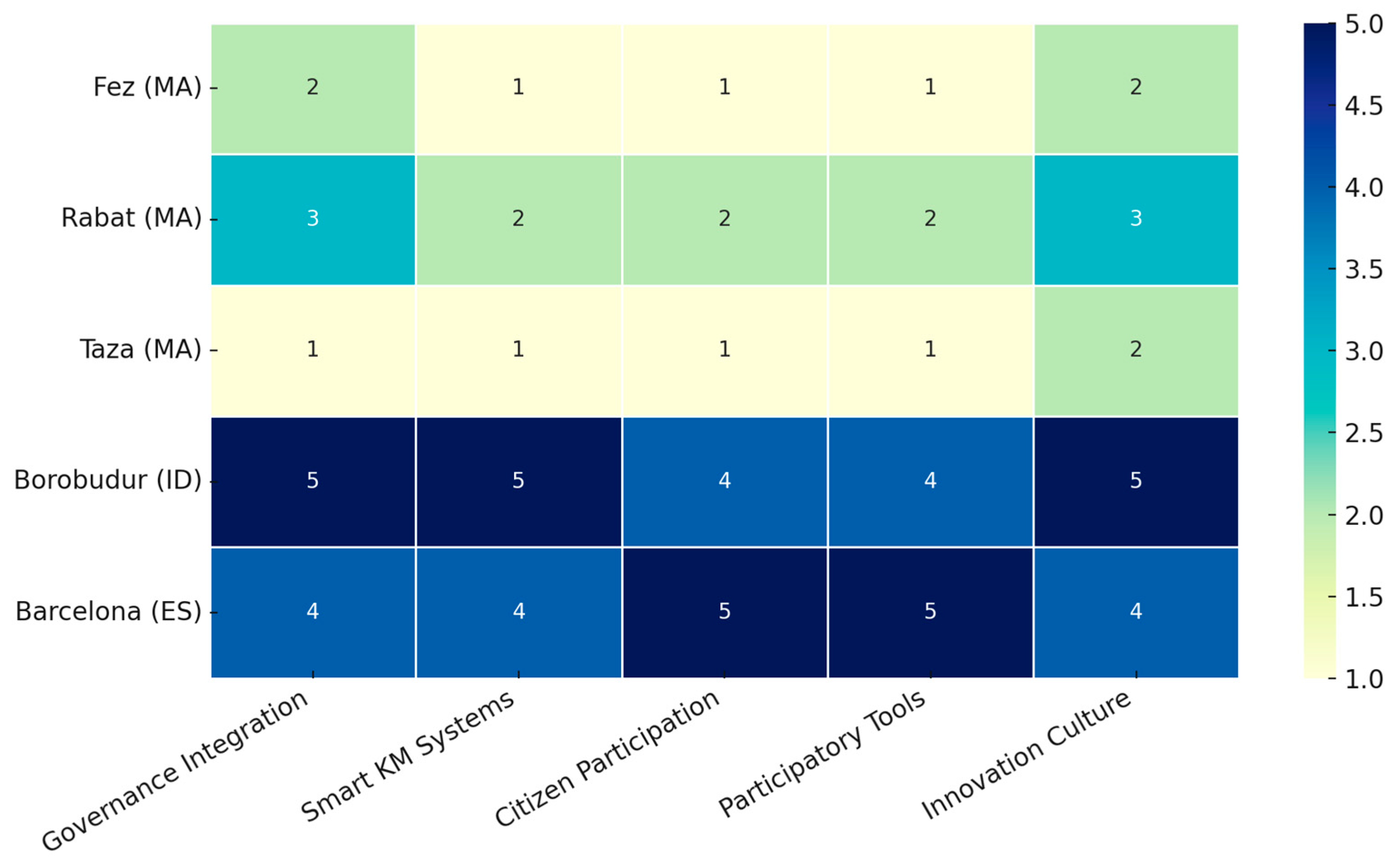

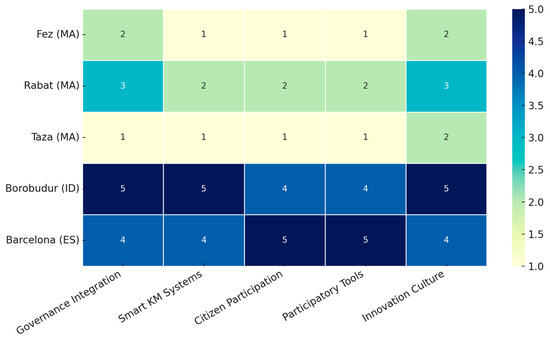

To evaluate and visualize the performance of each city or initiative across heritage governance dimensions, a structured scoring framework was applied. Five dimensions were used for assessment: (1) cross-sector coordination, (2) Smart KM infrastructure, (3) citizen participation, (4) policy integration, and (5) digital tool implementation. Scores ranged from 1 (very weak or absent) to 5 (fully institutionalized) based on document analysis of policy reports, academic studies, UNESCO evaluations, and institutional charters. For example, Fez’s score in “cross-sector coordination” was derived from the 2020–2024 Fez Medina Program documentation and the INDH report [10]; Rabat’s digital implementation score used the GIS reports reviewed by Simou & Baba [11]. The authors assigned scores collaboratively using a standardized rubric and cross-validated entries through triangulation with multiple sources. Heatmap values represent the average score per dimension per city, normalized on a 1–5 scale for comparative clarity.

Additionally, a mapping of the digital tools and platforms used in both Moroccan and international heritage initiatives was carried out. Each tool was categorized by function (documentation, planning, visualization), type (GIS, 3D scanning, VR/AR, crowdsourcing), and level of integration (pilot, isolated, or institutionalized).

4. Results

This section presents the results of a multi-source analysis combining case study comparison, document review, and literature synthesis. Aligned with the paper’s three central research questions, the findings are organized thematically around governance structures, Smart KM, and citizen participation.

4.1. Governance Structures

Across all Moroccan case studies, a recurring pattern reveals that strong national-level commitment to heritage preservation exists, but institutional coordination remains inconsistent and, in some cases, completely lacking. As emphasized in the Figure 1, the Fez Medina Rehabilitation Program exemplifies this disconnect. While it benefits from direct royal support and long-term investment, it still operates with minimal horizontal coordination. Ministries of culture, housing, tourism, and urban development often work in silos with overlapping mandates and little shared planning [1,12].

Figure 1.

Findings through a heatmap that scores each city or country across five heritage governance dimensions. Morocco’s cities score low in cross-sector coordination and inclusive governance compared to global benchmarks.

In Rabat, where smart city initiatives have been promoted on paper, practical implementation remains fragmented. Although GIS-based inventories for heritage documentation exist, they remain mostly internal to municipal departments and rarely contribute to shared planning or public access [7]. Taza, as a smaller city with fewer resources, faces even deeper governance challenges. Project leadership is unclear, responsibilities are often diffuse, and participatory channels are virtually absent [2].

In contrast, international cases demonstrate clearer and more coherent models. In Barcelona, heritage governance is embedded into urban policy through participatory planning, cross-department collaboration, and citizen co-governance structures from the early stages of project design [3].

4.2. Smart KM

A second key finding is the limited presence and even weaker implementation of Smart KM systems in Morocco’s heritage projects. While some initial efforts have been made such as Rabat’s use of GIS to document heritage zones, these tools are not well integrated across institutions. Most data are fragmented, kept within separate departments, or lost during administrative transitions. Cities like Taza lack a centralized system for archiving restoration records, architectural plans, or oral histories.

This gap has serious consequences. Without functional knowledge platforms, heritage data cannot support continuity, innovation or inter-institutional learning. Worse still, the absence of Smart KM creates room for redundant efforts, politicization of narratives, and a gradual loss of cultural memory as projects and personnel shift over time.

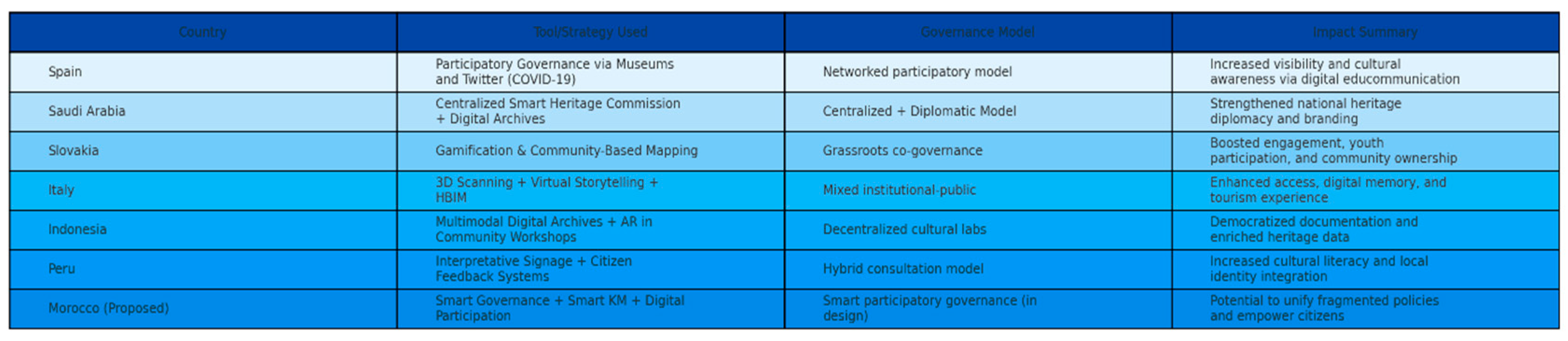

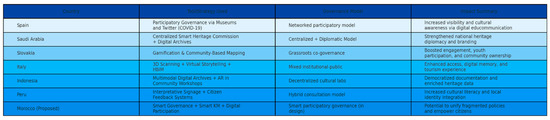

By contrast, as illustrated in the Figure 2, Indonesia’s Borobudur project provides a clear example of what Smart KM can enable. There, digital archives are combined with 3D modeling, storytelling tools, and open-access systems that serve not only heritage professionals but also tourists, students, and local residents [5].

Figure 2.

Smart KM implementation in different countries.

4.3. Citizen Participation

Perhaps the most striking contrast in this study lies in the role of citizen participation in heritage governance. In Morocco, citizen involvement is largely symbolic. In Fez for instance, consultation sessions are often held but usually after core decisions have already been made. These forums tend to function more as public validation mechanisms than as genuine participatory spaces.

In Rabat and Taza, the picture is even more limited. No digital platforms were identified that enable communities to actively contribute to heritage documentation, planning or evaluation. Participation is rarely embedded structurally; it is treated as an optional add-on, not a core component.

International case studies suggest alternative pathways. Slovakia has adopted gamified mobile apps that engage citizens in real-time storytelling and data collection for heritage mapping [8]. In Sicily, digital storytelling projects empower communities to narrate their own connections to historic sites, often challenging top-down narratives [13,14]. Indonesia’s Borobudur workshops offer a deeper model; they do not just inform locals but they train and co-author projects with them [5].

5. Discussion

The study finds that despite Morocco’s ambitious cultural heritage preservation and smart city initiatives driven by political vision, the supporting systems for long-term impact are still underdeveloped. In cities like Fez and Rabat where substantial funding and attention have been directed, heritage projects still struggle with fragmented governance, limited coordination between institutions, and the near absence of participatory mechanisms. Despite occasional digital experiments, there is no real Smart KM infrastructure to connect ministries, municipalities or communities in meaningful or lasting ways.

In practice, this means that heritage interventions are often designed and implemented as standalone projects lacking a system-wide view. The absence of an integrated knowledge ecosystem leads to inefficiencies, repeated mistakes, and the gradual erosion of institutional memory. Equally concerning is the near-total absence of citizen co-creation. While public consultation is sometimes referenced in policy language, citizens are rarely invited to shape heritage priorities in practice. These challenges are not entirely unique to Morocco, but they represent a missed opportunity at a time when global heritage governance is shifting toward more inclusive, digitally enabled, and knowledge-driven models.

5.1. Reframing Cultural Heritage Through a Smart Governance Lens

One of the key insights from the international case studies is that effective heritage governance extends beyond the mere application of technology. It is about embedding collaborative intelligence into the very way we plan, govern, and sustain cultural resources. In Barcelona for example, heritage management is tightly woven into urban policy and participatory planning. In Indonesia and Slovakia, digital tools are not treated as gimmicks, rather they are ways of documenting stories, engaging youth, and opening space for multiple interpretations of history [3,5,8].

This broader vision reframes heritage not as something to merely protect but as something living, something to be co-managed, adapted and integrated into everyday urban life. Smart governance in this sense moves beyond the technical. It becomes a platform for trust-building, learning, and future-making.

5.2. A Moroccan Pathway: The “Triple-I Framework”

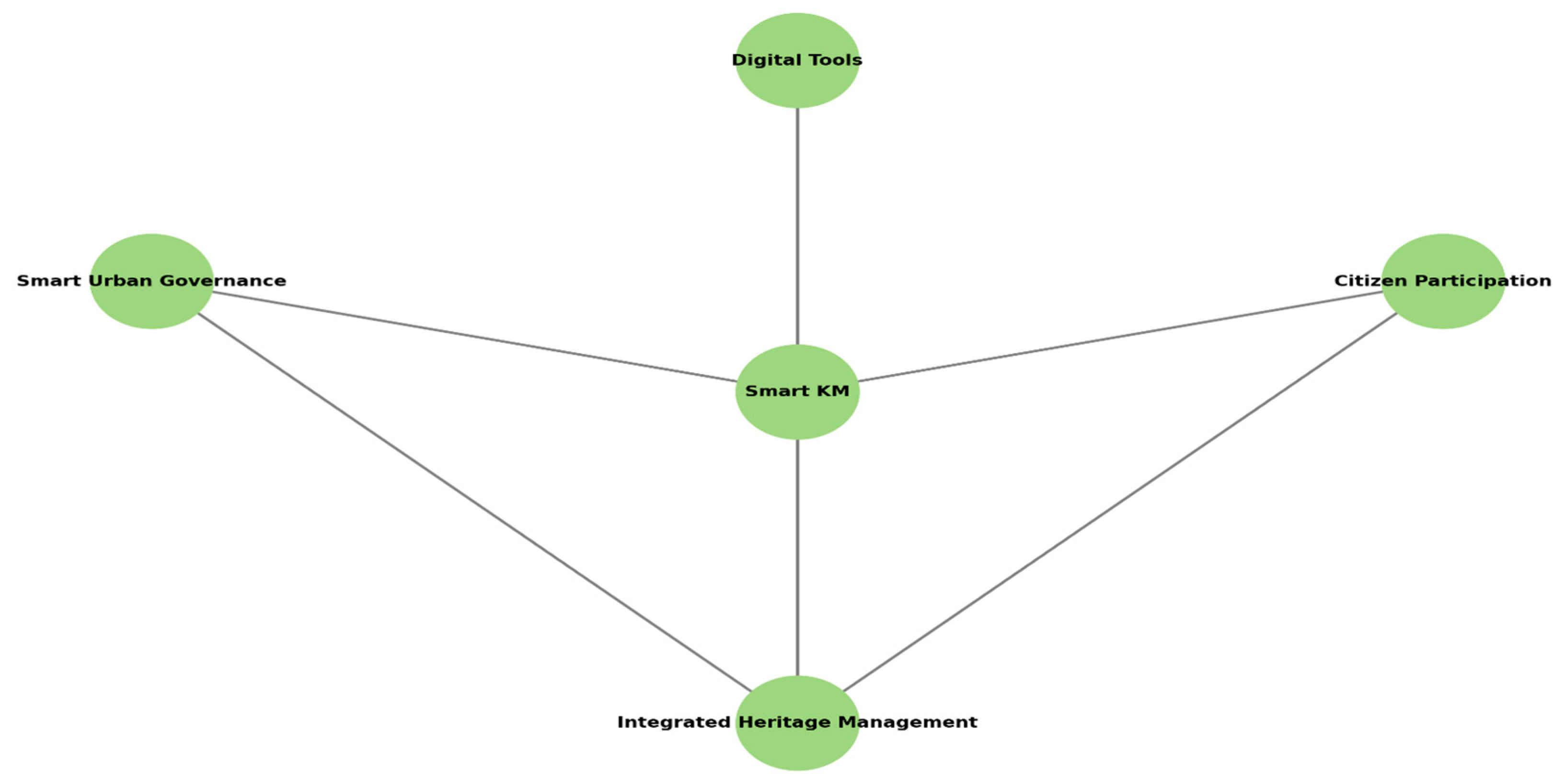

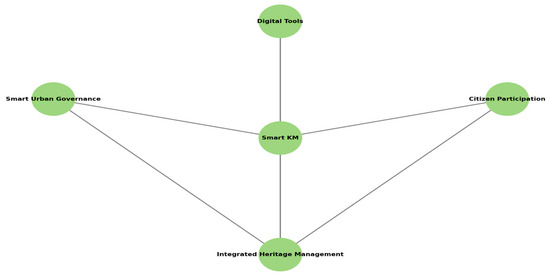

In response to the gaps identified throughout this study, this paper proposes a conceptual roadmap, as described in the Table 1 and Figure 3, tailored to Morocco’s context, the Triple-I Framework, built around three interconnected pillars: Integration, Intelligence, and Inclusion.

Table 1.

The Triple-I Framework.

Figure 3.

The conceptual framework for integrated heritage management.

Integration involves aligning national, regional, and municipal actors. Despite Morocco’s high-level political commitment, heritage governance remains fragmented. Feasibility requires creating inter-ministerial heritage councils and appointing dedicated heritage officers at the municipal level. Initial pilot projects with the Ministry of Culture in cities like Fez and Rabat can expand based on performance reviews.

Intelligence focuses on developing Smart Knowledge Management systems. Fez has GIS inventories and 3D scans, but they lack interoperability. Starting with a central heritage data repository linked to universities, NGOs, and cultural agencies is feasible.

Inclusion needs participatory tools beyond symbolic consultation. Morocco can learn from Slovakia’s mobile storytelling apps and Indonesia’s community workshops. Integrating these into education programs, local festivals, or planning portals is feasible. Low-tech options like youth photo archives, school competitions, and community mapping days offer impactful, low-cost solutions.

The goal is not perfection but progress. By adopting the Triple-I Framework, Morocco could begin shifting from a preservation-first mindset toward a more resilient and collaborative heritage strategy that aligns with both UNESCO’s vision for inclusive cultural governance and broader smart city development goals.

5.3. Policy and Research Implications

Implementing the Triple-I model would require more than isolated reforms. It would mean rethinking heritage policy as part of Morocco’s broader digital and urban agendas. This includes creating smart city heritage strategies at the national level, investing in cross-sector capacity building, and training not just engineers and planners but also educators, cultural practitioners, and local government staff.

From an academic standpoint, the framework offers a way to evaluate and design smart heritage systems in contexts where cultural richness often outpaces technical readiness. Future research could explore how each pillar of the Triple-I model performs in different Moroccan cities. Case studies might track how communities engage with mobile apps, how municipal officers collaborate across departments or how digital archives grow and evolve over time. The answers could not only refine the model but also strengthen the case for smarter, more human-centered heritage systems across the Global South.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate how smart governance, Smart KM, and participatory digital tools can enhance the effectiveness and inclusivity of cultural heritage preservation efforts in Morocco. Using a comparative, document-based approach grounded in case studies and global literature, the research aimed to understand not just what is working but what is missing. What emerged in this paper was a complex picture, one in which Morocco’s undeniable political will to protect heritage often runs up against deeply rooted structural challenges.

Despite high-profile investments and political attention, particularly in cities like Fez and Rabat, heritage governance in Morocco remains fragmented and overly centralized.

One of the most critical insights also concerns the absence of robust Smart KM systems. In fact, across all Moroccan case studies there is little to no evidence of interoperable digital archives, shared planning platforms or frameworks for knowledge reuse. As a result, even successful heritage interventions tend to be temporary, isolated from one another and vulnerable to administrative turnover. In contrast, the international context demonstrates how Smart KM, when paired with participatory strategies, can radically improve both outcomes and public legitimacy.

Equally important is the issue of participation. The study found that in most Moroccan contexts, citizen involvement is symbolic at best. Participation is typically limited to consultation meetings held after core decisions have already been made. This not only weakens local ownership but also cuts off access to the lived knowledge and emotional ties that residents have to heritage spaces. The comparison with more inclusive international models suggests that participation is not a luxury but is a critical input for resilience, creativity, and long-term impact.

Methodologically, the study’s approach centered on comparative case analysis, document review, and visual synthesis proved effective in compensating for the lack of field interviews. This suggests that even under time and resource constraints, meaningful insights can be generated through multi-source synthesis grounded in a strong conceptual framework.

Several key recommendations follow from these findings. The first one is that Morocco should prioritize the development of interoperable Smart KM platforms at both the national and municipal levels. These platforms should not only store data but also enable cross-sector learning, collaboration, and public access. The second one is that the institutional reform should urgently clarify governance mandates and create better alignment between central authorities and local heritage actors. The third one is that the deployment of participatory tools, ranging from mobile heritage apps to school-based mapping programs, must be treated as more than pilot projects. They should be integrated into official planning cycles and evaluated for long-term value. Fourth, experimental “heritage innovation labs” could be launched in cities like Fez or Rabat to serve as spaces for co-design, testing, and scaling of smart cultural strategies. Finally, any of these efforts will require sustained capacity-building; municipal officers, educators, architects and civil society organizations all need the skills to operate within a digital and participatory heritage ecosystem.

In the end, this paper adds to a growing body of work that treats heritage not as a frozen relic of the past but as a dynamic interface between identity, memory, technology, and citizenship. Morocco, with its layered cultural depth and rising urban ambitions, is uniquely positioned to lead in this space. But doing so will require a shift from a legacy model of preservation to one that values inclusion, knowledge, and innovation. Furthermore, future research could extend this conversation by engaging directly with citizens and evaluating the socio-economic impact of digital heritage tools or piloting co-creation models across different Moroccan regions. In doing so, the gap between vision and implementation will help position heritage as a cornerstone of sustainable and inclusive urban futures that would significantly change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.H. and N.A.; methodology, D.E.H. and N.A.; software, D.E.H. and N.A.; validation, D.E.H. and N.A.; formal analysis D.E.H. and N.A.; investigation, D.E.H. and N.A.; resources, D.E.H. and N.A.; data curation, D.E.H. and N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.H. and N.A.; writing—review and editing, D.E.H. and N.A.; visualization, D.E.H. and N.A.; supervision, D.E.H. and N.A.; project administration, D.E.H. and N.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Belyazid, S.; Haraldsson, H.V.; Sverdrup, H. A sustainability assessment of the urban rehabilitation of Fez, Morocco. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 68, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Jaouad, M.; Chouitar, A. Territorial governance and the rehabilitation of old cities in Morocco: The case of Taza. Rev. Marocaine D’évaluation 2020, 14, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Colomer, L.; Pastor Pérez, A. City Governance, Participatory Democracy, and Cultural Heritage in Barcelona, 1986–2022. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2024, 15, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almakaty, S.S. Preserving and Promoting Saudi Heritage Nationally and Globally: The Role of the Saudi Heritage Commission. J. Ecohumanism 2025, 4, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokka, S. Governance of cultural heritage: Towards participatory approaches. ENCATC J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2021, 11, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Culture: Urban Future—Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Represa-Pérez, F.; Vázquez-Cuevas, M.J.; Zepeda-Becerra, A.L.; Álvarez-Figueroa, J. The Liguiqui Archaeological Park-Museum as a Participatory Proposal for Sustainable Community Development. Rev. Mus. Antropol. 2024, 17, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomadaki, O.I.; Dimoulas, C.A.; Kalliris, G.M.; Paschalidis, G. Digital Storytelling and Audience Engagement in Cultural Heritage Management: A Collaborative Model Based on the Digital City of Thessaloniki. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Initiative Nationale pour le Développement Humain (INDH). Rapport Annuel sur la Réhabilitation Urbaine et Culturelle; INDH: Rabat, Morocco, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Simou, H.; Baba, R. A GIS-based methodology to explore and manage the archaeological heritage of Rabat. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Culture, Maroc. Programme de Réhabilitation de la Médina de Fès; Gouvernement du Maroc: Rabat, Morocco, 2019.

- Bonacini, E. Engaging participative communities in cultural heritage: Use of digital storytelling in Sicily. Int. J. Digit. Humanit. 2019, 3, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacini, E. Participatory storytelling, 3D digital imaging and museum studies: A case study from Sicily. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 14, e00112. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).