1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of the Reading Experience in This Study

In this study, “reading experience” is not limited to the act of reading but is defined as a full process that starts with encountering a book, continues through reading, and includes the feelings and thoughts afterward, as well as sharing of the experience with others. In other words, reading is a layered experience that goes beyond understanding stories or taking in information. It connects deeply with the reader’s emotions, memories, and values, and the entire process before, during, and after reading should be seen as the full “reading experience”. Iwasaki (2021) [

1] described the relationship with books using words like “seeing, smelling, decorating, thinking, feeling, tasting, touching, flipping, listening, loving, connecting, and encountering”, showing that the value of the reading experience includes physical, emotional, and social aspects that go beyond just “reading”. This study also follows that opinion and sees the reading experience as not only an interaction with the text, but also a full experience that happens in daily life and cultural settings involving books.

Today, in addition to paper books, digital books and audiobooks are widely used, and the ways and situations of reading have also changed. Because of this, the quality of reading experiences is also changing, making it possible to get deeply involved, share, and remember the reading in new ways. Features like search and highlight in e-books, reading record apps, and sound-based memory in audiobooks show new kinds of reading experiences that did not exist with paper books. On the other hand, the feeling of touching a real book, the texture of the paper, writing notes, and using bookmarks remain important, and they make the reading experience richer for the senses.

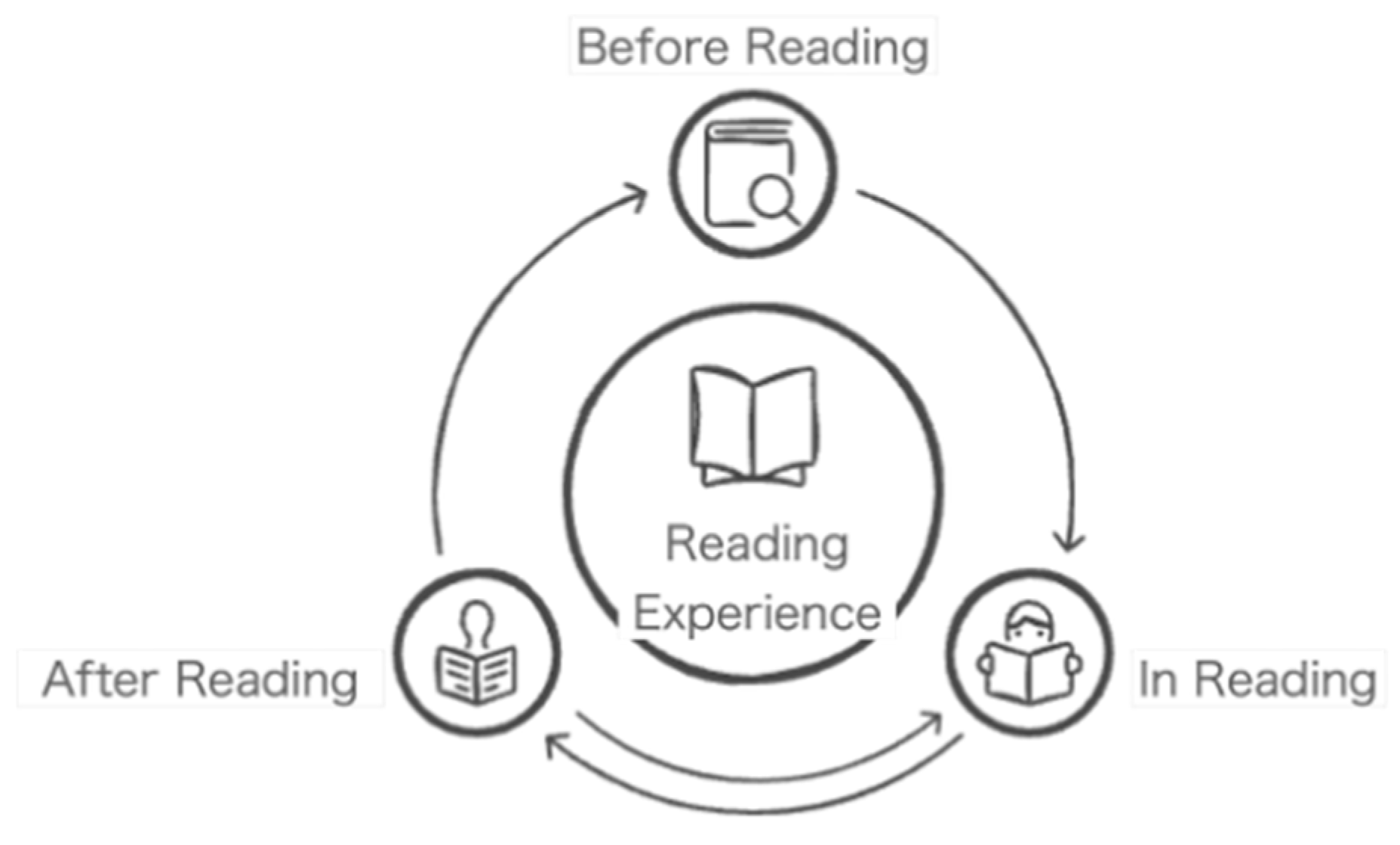

Figure 1 shows an image of the reading experience over time.

In the “Before reading” section, the focus is on how the reader finds a book and what kind of hopes or reasons they have for starting to read it. For example, a reader might pick up a book because its cover caught their eye in a bookstore, choose a book from a library shelf by topic, or find a book through social media recommendations or bestseller lists. The act of choosing a book is closely related to the reader’s values and interests. In this stage, hopes, feelings, and background knowledge before reading work as the foundation of the reading experience. In the “In reading” stage, the reader becomes absorbed in the world of the story or logic, and experiences inner changes like feeling close to or rejecting characters or ideas, remembering things, or gaining new insights. Reading often leads to a kind of talk with oneself and becomes a deep emotional experience, not just a way to obtain information. While reading, certain words or scenes may stay in the reader’s mind, and their feelings or values may change. This part of the experience is a process where the reader’s inner self is inspired and changed by a kind of talk with the book, which is like another person. The “After reading” experience includes a feeling of accomplishment and reflection, where the reader puts their thoughts and feelings into words and keeps them in memory. Talking with friends about the book or writing reviews on social media or reading apps after finishing it helps give the personal reading experience new meaning through sharing with others. Also, when people reread the same book after some time, they often have different thoughts or feelings than they did the first time. For example, when someone rereads a philosophy book they read as a student after becoming an adult, they may find new meaning in parts they could not understand before. This kind of rereading also shows how reading experiences can continue and grow deeper over time.

As we have seen, the reading experience does not end as a single act. It is a dynamic experience made up of a flow: expectations and choosing a book before reading, inner change during reading, and sharing and rethinking after reading. This process includes many things such as the reader’s senses, memories, communication with others, and the social setting, and it keeps changing and growing. When we study the reading experience, we should not only focus on understanding the text. We also need a broad view of where and when reading happens, and how people’s feelings and relationships are integrated into it.

In addition to viewing the reading experience along the time flow of “Before”, “In”, and “After” reading, this study also sees it as important to focus on the “space” of the reading experience, where and in what kind of setting reading takes place. The “space” does not only mean a physical place. It also includes the situation and relationships in which reading happens. The social and meaningful “space” of the experience.

We considered this spatial reading experience in two related ways: one is the “inward” reading experience, and the other is the “outward” reading experience. The “inward” experience is personal, a quiet, deep reading by the reader based on their own interests and inner needs. For example, reading a diary-like essay, a poetry book, or a novel alone at night is a typical “inward” reading experience. It helps the reader reflect on their own memories and feelings. This kind of reading is carried out away from others’ views and social expectations. It takes place in a very private space and often helps the reader feel calm and heal themselves. On the other hand, the “outward” reading experience is social, and reading grows through contact with others. This can be found in social and shared forms of reading, such as book clubs, sharing book records and reviews on social networking services, and participating in events at libraries and bookstores. Through others’ opinions and thoughts, readers can see the book in a new way and rethink their own views. This kind of reading connects the reader not only to the book but also to other people and communities. It becomes an experience that spreads beyond the individual, like a network.

Recently, on social media, especially among Generation Z, “reading accounts” have become popular. People share pictures and comments about their reading and talk with followers. This is a strong form of “outward” reading experience. Reading is no longer something performed alone, as a personal diary for most people has now turned into a blog and other SNS media, and it always has the possibility of connecting with others. The way people show their reading can become part of their self-image and way of talking with others.

In this way, the reading experience is not only about the flow of time, but it also depends on where and with whom the reading takes place. “Inward” and “outward” are not opposites; they often mix and shift between each other. For example, talking about a touching book with someone can turn a private moment into an outward experience. Also, a book recommended by someone else might still lead to deep personal reflection. Seeing the reading experience as something that moves between these two sides helps us understand the full picture of reading in a richer and deeper way. The reading experience has not just a time flow but also a space that moves between inward and outward. It should be redefined as a multidimensional activity. Through books as cultural tools, readers can talk to themselves and connect with others. Reading can be seen as a changing process that moves between those two ends.

1.2. Rereading and the Reading Experience

Rereading refers to the act of reading a book again after having once finished it. However, it is not merely a repetitive act. It is a significant activity that reflects the reader’s internal changes and deepens and expands the reading experience both temporally and spatially. This study views the reading experience along the temporal axis of “Before reading”, “In reading”, and “After reading”. Rereading belongs especially to the “After reading” stage. Yet it also guides the reader into a renewed experience of “In reading”. Thus, it provides a perspective that understands the temporal axis as circular and dynamic. In other words, rereading recalls memories of reading, and it becomes an intellectual and emotional act of reconstructing and updating those memories.

When rereading, the reader brings together various factors such as memories of the first reading, emotions at the time, reading comprehension, and life circumstances. The reader then engages with the work once more from their current point of view. For instance, when reading a novel by Haruki Murakami during one’s student years, the reader may have empathized with the protagonist’s loneliness and sense of isolation. However, upon rereading after gaining work and life experience as an adult, the same reader may come to focus on the complexity of human relationships and the weight of ethical choices in the story. This shift in interpretation shows how rereading reflects the reader’s inner growth over time and becomes a process that fosters deeper self-understanding.

Furthermore, rereading emphasizes less the value of a book as an “information source” and more the value of the “reading experience” itself. The first reading often involves acquiring new knowledge and information. In contrast, rereading involves reconstructing what is already known. This often deepens immersion into the rhythm of the language, the structure of the text, and the inner portrayal of characters. Therefore, rereading is not simply the repeated consumption of a book as an information source. Rather, it is a reunion with a story that lives on in memory and experience. It is a deepening of the reading experience, wherein the reader continuously renews personal meanings. Therefore, rereading differs from reading for information. It is an emotional and intellectual act led by the reader.

Moreover, in classical literature and philosophical texts, annotations are a crucial element that makes rereading possible and enriches its quality. For example, in classical works such as The Tale of Genji or Essays in Idleness, due to differences in language and the complexity of cultural background, comprehension is difficult without annotations. Annotated editions such as those from Iwanami Bunko or Chikuma Gakugei Bunko provide readers with guides for interpretation and clarify themes and contexts that may have been overlooked in the first reading. In this way, rereading transforms from the act of interpreting a work into a dialogic interaction with it, resulting in a more active and critical reading experience.

The digitization of reading environments has further diversified the modes of rereading. Functions such as highlighting and note-taking in e-books allow for readers to easily revisit important points and thoughts recorded during the first reading. This creates a structure where the reader engages in a dialogue between their past and present selves. Thus, rereading becomes a space for introspective self-reflection, while also highlighting the continuity and multilayered nature of reading as a practice.

Rereading also serves as a bridge between the “inward”, personal reading experience and the “outward”, socially extended reading experience. In the act of rereading, the reader engages in a personal process of reinterpretation based on their own experiences, while also encountering layers of interpretation and annotation created by others. This enables interaction with a broader, collective reading culture. Thus, rereading allows for an individual to deepen their own reading experience, while also forming a richer relationship with books as shared cultural resources. In summary, rereading is both an extension of the “after reading” experience and the beginning of a new “In reading” experience. It is a reading activity that contains both inward and outward dimensions. In this sense, rereading embodies the dynamic and multilayered nature of the reading experience. It is a vital practice for reaffirming the material, informational, and sensory value of books. Reading is a continual renewal of the act of reading. Rereading is a central activity in that process, and it deserves further attention in future reading research.

1.3. Social Annotation and the Reading Experience

The reading experience comprises an “inward”, personal and introspective aspect, and an “outward”, interrelation aspect that opens toward others. This section focuses on the latter, the outward-oriented reading experience, and discusses its historical development and contemporary transformations. Reading is often described as a solitary activity; however, in modern reading culture, the practice of reading with others—that is, dialogical and social engagement through reading—has been emphasized. For example, in Japan, from the Meiji period onward, literary circles and reading groups began to form, and spontaneous reading activities by citizens gradually expanded. According to Iwai et al. (2020) [

2], such cultural activities mediated by reading expanded significantly after World War II. Especially during the period of rapid economic growth from the 1960s onward, public libraries became hubs where citizens voluntarily gathered for reading groups, lectures, and exhibitions. Consequently, libraries evolved from mere book lending institutions into spaces for shared reading and dialogue, functioning as “forums for citizens”. The spread of such citizen-led reading initiatives has promoted the formation of grassroots reading groups rooted in local communities, thereby contributing to the transformation of reading into a social and cultural practice. Furthermore, Sakauchi (2016) [

3] highlights the role played by private library initiatives within Japan’s library culture. Particularly after the war, while institutional development of libraries progressed, in regions and communities underserved by such services, citizens actively organized home libraries and community-based book initiatives to support reading. Momoko Ishii’s “Katsura Library” and Ken Namie’s “Machida Community Library Movement” exemplify efforts to foster children’s cultural environments through reading and also serve as opportunities to reconsider the role of public libraries. These initiatives symbolize the collaborative construction of reading environments between libraries and citizens and illustrate how shared reading experiences have become embedded in local communities. Thus, postwar Japanese reading culture has developed through the dual mechanisms of institutionalized libraries and voluntary private book initiatives. In these reading groups, individual readers articulate their interpretations and exchange views with others, which relativizes the content and deepens understanding, often motivating rereading. In other words, the outward-oriented reading experience has transformed reading from a unidirectional act of acquiring knowledge into a dialogical and recursive process that is continually reshaped through interaction with others.

Today, the spread of the internet and social media has further expanded the outward-oriented reading experience. “Reading Meter” is a social-network-style reading record service mainly used in Japan, featuring functions such as logging books read, posting impressions, and user-to-user interaction through follows and comments. “Booklog” provides comprehensive review and bookshelf features, allowing for users to build their own personalized “bookshelf” online. “Goodreads” is widely used in the English-speaking world, offering extensive functions such as reviews, ratings, and reading challenges, along with active communities focused on specific genres and authors. These reading log services enable readers to publicly share their reading history and impressions, and to easily engage with others’ perspectives. These platforms primarily focus on the “After reading” stage and function as mechanisms that shift the meaning of reading from a personal experience to a socially contextualized act through recording and sharing. On social media, real-time reviews and interpretations of specific works are frequently shared, leading to cyclic reading experiences where other readers are inspired to revisit the same texts. Among such examples, the “Popular Highlights” feature on Kindle represents a modern and symbolic instance of the outward-oriented reading experience. This feature displays passages that many readers have highlighted, enabling users to see points of interest during their own reading process. As a result, the inherently private act of reading becomes subject to others’ attention even during the reading itself, creating a structure in which the presence of others intervenes in the meaning-making process in real time.

In recent years, reading support tools utilizing natural language processing models such as GPT and BERT have also emerged. For example, the U.S.-based startup “Perusall” is a social annotation platform powered by AI that supports reading activities by enabling students to comment in real time while reading and by using AI to facilitate discussions. Tools such as “ShortlyAI” and “Explainpaper”, based on OpenAI’s GPT model, can automatically generate summaries and explanations of complex texts and academic papers, and are used as aids in academic reading. Moreover, “Khanmigo”, an educational support AI powered by GPT-4 from Khan Academy, can respond in real time to questions that arise during reading and provide supplementary explanations about the content and contextual background through dialogue. These AI-based reading support tools intervene in the processes of comprehension and reflection that accompany reading, enriching the reading experience by offering supplementary information and related knowledge in response to readers’ questions. For beginners or readers without specialized knowledge, AI-driven “annotative support” is expected to serve as a new tool for lowering barriers to accessing texts.

Table 1 shows the historical development of reading support methods and activities, and

Table 2 shows the characteristics and main issues of each type of reading support.

In this way, reading experiences that involve interaction not only after but also during reading are entering a new phase, distinct from conventional reading groups or SNS-style sharing. That is, through real-time annotation and highlight sharing, “reading time” and “sharing time” overlap, making reader interpretations flexible and subject to immediate transformation. In this process, others’ highlights and annotations function not merely as reference materials but as mechanisms of “co-reading” that influence the reading act itself. Furthermore, such reading practices contribute not only to individual interpretation but also to the formation of collective intelligence. As annotations and highlights from multiple readers accumulate, traces of reading are embedded in the text, reconstructing the work as a medium of memory shaped by an intellectual community. This indicates that the knowledge generation and sharing functions once performed by reading groups are now being inherited in a more flexible and sustainable form through technological intervention.

The advancement of such outward-oriented reading experiences gives rise to new questions for readers and serves as a stimulus for further reading. In other words, others’ readings intervene in one’s own reading experience in real time, generating a cycle that encourages rereading and reinterpretation. Thus, reading is no longer a one-time act of information intake but is positioned as an ongoing process that continuously intersects with others. This study examines how such outward-oriented reading experiences influence rereading and the deepening of interpretation and considers the social dimension of reading through real-time annotation and sharing functions. Outward-oriented reading, grounded in past cultural reading practices, opens new horizons through digital technologies, and its potential offers an important perspective for reflecting on the future of reading culture.

1.4. Significance and Novelty of This Study

This study focuses on the relationship between “rereading” and “annotations” in the reading experience, and its significance lies in comparing and analyzing how traditional annotations and reader-participatory annotations influence understanding and enjoyment of reading. In traditional literary studies, academic annotations have been used to interpret the background of the work and the author’s intention. However, with the recent development of digital technologies, a culture has emerged in which readers freely share their interpretations and add their own annotations. This study examines how the meaning of “rereading” is changing within this new reading environment, and it is expected that the results may also contribute to providing a new approach in literary studies.

This study may also offer a new perspective in the field of reading education. Traditional reading instruction has mainly aimed at understanding the content of the work and grasping the author’s intention. In recent years, however, more attention has been given to the importance of active interpretation and interactive reading experiences by readers. In particular, when readers add annotations by themselves and share them with others, it can create diverse perspectives and make reading a more active process.

Furthermore, this study also pays attention to the fact that the spread of e-books and online reading platforms has made it easier for readers to share their thoughts and reflections, and that such social media-style annotations are becoming an important part of the reading experience. By examining whether reader-participatory annotations promote rereading and deepen the reading experience, this study aims to explore a new form of reading in the digital age.

In summary, this study aims to clarify the changes and possibilities in the modern reading experience by focusing on the relationship between rereading and annotations, and the findings are expected to offer useful insights into literary studies, reading education, and digital reading environments.

1.5. Previous Research

This section provides an overview of previous studies on rereading and annotation and clarifies how each relates to the present study. Based on insights into the effects of rereading on the reading experience, the forms and functions of annotation, and interaction with readers, this study is situated within an appropriate theoretical framework.

First, the study “Use of a Social Annotation Platform for Pre-Class Reading Assignments in a Flipped Introductory Physics Class” by Miller et al. (2018) [

4] used the online platform “Perusall” to allow for students to annotate texts and engage in discussions with one another, demonstrating that reading comprehension and learning outcomes improve through this process. As readers respond to each other’s annotations while reading, reading shifts from a passive activity to an active and dialogic one, which also leads to increased motivation for rereading, an aspect of particular relevance. This study directly relates in that the incorporation of social media-style annotations may enhance the interactivity of the reading experience and promote rereading.

In “From the margins to the center—The future of annotation” by Wolfe and Neuwirth (2001) [

5], the discussion begins with the annotation practices found in medieval manuscripts and proceeds to examine how digital technologies have re-enabled the sharing of annotations in the modern context. The perspective that annotation functions as a tool to visualize readers’ thoughts and facilitate intellectual dialogue with others is closely related to the design philosophy of the reading support system proposed in this study. In particular, the act of referring to others’ annotations during rereading serves as a trigger for new insights and deeper interpretation, providing a theoretical foundation for this study.

In “Reading Support for Aozora Bunko through Automatic Annotation Generation [Japanese translation by the author]” by Hayami and Inoue (2014) [

6], a system was developed that uses AI to automatically identify difficult words and generate annotations. Although issues remain regarding the quality and reliability of the annotations, its ability to support comprehension without disrupting the reader’s rhythm is noteworthy. Although this study does not focus on the use of AI in the annotation function, the supportive role of annotations and their appropriateness offer valuable insights when considering how such features affect the reading experience from a technological perspective.

In “Development and Evaluation of the WebMemo System Enabling Annotations on Web-based Learning Materials [Japanese translation by the author]” by Itō et al. (2006) [

7], it is shown that learners deepen their understanding upon review by making annotations on web-based learning materials. This empirically demonstrates the effectiveness of having readers record their own annotations for rereading. It supports the effectiveness of the “reader-authored annotation” function proposed in this study. In particular, the experience of engaging in a dialogue with one’s past thoughts during rereading suggests the potential for a deeper reading experience.

Among studies focused specifically on rereading is “On the effect of Long-term Rereading ascertained from analysis of a reading report” by Hosohara and Momohara (2018) [

8]. Their investigation using

The Little Prince revealed that repeated rereading led to changes in reading styles and encouraged attention to symbolic elements. The study shows that rereading is not merely repetition and are closely relating to the present study’s underlying aim of re-evaluating the value of rereading. Moreover, the process in which readers actively reread and gain new insights connects to the potential of annotation-based reading support.

In “First Reading and Rereading in Japanese Language Education [Japanese translation by the author]” by Adachi (2018) [

9], focus is placed on the processes of prediction and revision during the first reading. The study examines how rereading alters the quality of reading in an educational setting. It clarifies the process through which rereading practices change readers’ interest and interpretive perspectives on a work. This aligns with the secondary objective of the present study, which emphasizes the educational value of rereading.

Finally, “Creation of Sentiment Corpus by Multiple Annotators with an Annotation Tool that has a Function of Referring Example Annotations” by Miyazaki and Mori (2025) [

10] demonstrated that referring to annotation examples is effective in increasing consistency among multiple annotators. This indicates that the reliability and consistency of annotations significantly affect readers’ understanding and reception. This point is also important in our study. It supports discussion on how readers interpret diversity when encountering multiple annotations during rereading.

Each of these previous studies clarifies the significance and impact of rereading and annotation from distinct perspectives. Building on these findings, this study focuses on the role of annotation in the rereading experience of literary works, examining how both traditional and social media-style annotations influence reader comprehension and motivation to reread, and aims to establish a theoretical foundation for future empirical research.

1.6. Purpose

The final objective of this study is to explore how digital technology is changing our relationship with books and, more broadly, reading culture, in order to create a richer reading environment. In this paper, the focus is on the reading experience after the first reading, and a system is proposed to clarify the effects of rereading and the role of annotations in supporting it. In traditional literary studies, annotations have functioned as tools to convey expert knowledge or to help readers understand a work, but they have not paid much attention to the active involvement of readers during rereading or the interactive aspect of reading through annotations. Also, although there are some examples of systems using annotations in the fields of informatics and educational technology, they mainly aim to support first-time reading and give little attention to the dynamic aspects of rereading, such as reinterpreting annotations or changes in their meaning. Furthermore, there are few studies that examine, through experiments or system design, the differences in reading experience caused by traditional and social media-style annotations. In particular, system-based approaches to support rereading by general readers are still underexplored in academic research, and this led to the present study.

The purpose of reading is not solely to acquire information. It is a dynamic process in which one’s first impressions and understanding change over time, and rereading brings new insights. However, many current reading support tools and annotation functions focus mainly on the first reading, and they do not place much importance on supporting the reader’s changes or deeper thinking during rereading. This study examines how rereading transforms the reading experience and proposes a system to explore how traditional annotations (based on literary analysis) and social media-style annotations between readers affect that process.

2. System Image

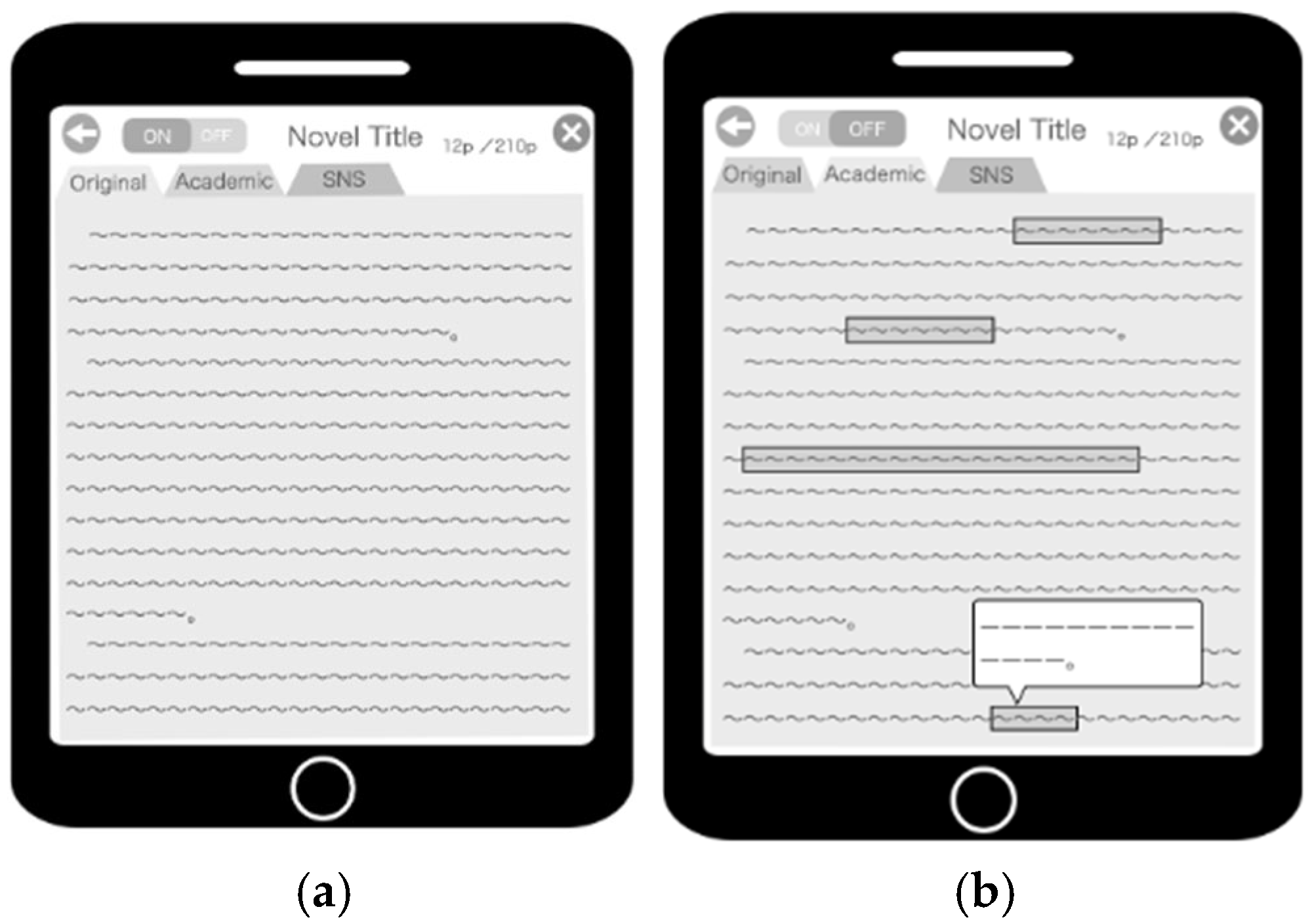

This study focuses on “rereading” as one factor that enriches the reading experience after the first reading and aims to explore its significance by comparing and analyzing how different types of annotations affect comprehension and immersion. This paper proposes an interactive reading support system that allows for readers to freely choose whether to view annotations and what type, and also to record and share their own interpretations. The system aims to maximize the value of rereading and to transform the reading experience into something more layered and evolving. This system is named “Echo Read” and is characterized by a tab-switching feature, similar to an index holder, for selecting annotation modes. Readers can switch among three modes to read in a way that suits their personal reading style:

Original (No Annotations)

This mode displays only the main text, providing a pure reading experience without extra information. It is designed especially for first-time reading, allowing for the reader to immerse themselves in the story without preconceptions.

Academic (Literary Research)

This mode provides expert knowledge such as the background of the work, the author’s intentions, historical context, and literary evaluation. The annotations are based on the insights of researchers and experts, helping readers understand the work in greater depth. By exploring symbolism, themes, and historical background, this mode aims to enhance discoveries during rereading and strengthen literary understanding.

SNS-style Annotations (Reader-Contributed Annotation)

This mode displays annotations and comments written by the reader and by other readers. By incorporating social networking elements, it encourages real-time discussion and exchange of opinions, enabling readers to engage with various perspectives. As a result, readers can compare diverse interpretations and grasp the work from broader viewpoints.

Figure 2 shows a system image. (a) shows the “original” mode, which displays text without annotations. (b) shows the “academic” mode, which displays part of the text surrounded by boxes indicating where annotations have been added. This system not only allows for users to view existing annotations but also provides the ability to freely write and store their own annotations. Readers can record their thoughts and questions on any page, and control whether to view their own annotations using an ON/OFF toggle at the top-left corner of the screen. During rereading, they can reflect on their past interpretations. These annotations can be saved privately as personal notes or shared with other readers. Moreover, readers can react to others’ annotations by showing agreement or finding them helpful, so that useful comments are highlighted. This helps to build an environment where high-quality annotations are collected, rather than just a list of comments.

In addition, to allow for readers to record different thoughts each time they reread, the system includes a feature that enables multiple annotations at the same point in the text. This makes it possible to compare past and present interpretations and reflect on how the reading experience has changed. Additionally, in the SNS-style annotation mode, an AI-based function will analyze each user’s annotation patterns and automatically assign tags. For example, the number of books read in specific fields such as philosophy, science fiction, or modern literature, and the tone of their comments (critical, emotional, analytical, etc.) are used to assign descriptive tags to users. Readers can view all users’ annotations, but they can also filter to view only those from users with specific traits of interest, based on these tags. For example, they can choose to display only comments from readers knowledgeable about history as #HistoricalInsight, or from those who focus on emotional impressions after reading as #Emotional, depending on their preference. This allows for easier access to annotations that are more personally meaningful.

By using this system, readers can choose different approaches between first reading and rereading. They can enjoy a diverse reading experience that was not possible with printed books. For instance, they can enjoy the story in plain text mode during the first read, deepen their understanding with expert annotations during the second read, and then explore others’ reactions and insights through social annotations, gaining new discoveries through those perspectives. Through this system, reading becomes more than a process of information intake. It also becomes a meaningful intellectual activity that deepens personal thought and generates dialogue with others. Furthermore, with the spread of e-books and audiobooks, reading is changing from a solitary activity to a shared experience through networks. This system aims to develop reading into an interactive activity even in digital settings, and to provide a new reading space where readers can deepen their thinking through communication with others.

4. Future Works

This study compares and analyzes the effects of different types of annotations during rereading. This will allow for us to examine how rereading contributes to the reading experience. For this purpose, the study sets three reading conditions using the proposed system—(1) reading without annotations, (2) reading with traditional annotations based on literary research, and (3) reading with SNS-style annotations including comments and thoughts from other readers—and compares the reading experiences under each condition. Participants are instructed to read the same literary work under all three different conditions. After reading, a questionnaire is conducted to assess their satisfaction, level of understanding, and changes in motivation to reread. Their reading behavior is also recorded, and their notes, highlights, and reactions to annotations are analyzed. Additionally, interviews are held after reading to gather qualitative data by asking about their motivation to reread and the impact of annotations on their reading experience. The questionnaire results are analyzed statistically to compare how each annotation condition affects comprehension, immersion, and new discoveries during the reading experience. The analysis focuses on identifying the factors that increase the motivation to reread, changes in satisfaction and understanding, and how helpful the annotations were perceived to be, all measured in numerical form to examine the differences between the conditions. The interview responses and reading notes are also analyzed to identify which kinds of annotations help deepen understanding. For example, the study looks at which annotations left the strongest impression and what new discoveries were made through rereading in order to explore qualitative changes in the reading experience.

Through this investigation, the study systematically examines how traditional annotations and SNS-style annotations each affect the reading experience. In particular, it tests whether traditional annotations enhance historical and literary understanding, supplement background knowledge, and increase motivation to reread. It also tests the hypothesis that SNS-style annotations, a new approach, increase enjoyment by including others’ viewpoints and encourage rereading by promoting post-reading discussions. The goal is to clarify the factors that promote rereading and the roles that annotations play in supporting it. Through the results of this study, it is expected to reconsider the value of rereading in today’s reading environment and offer a new perspective on how to support reading.