Food Supply Chain Traceability: A Multiple Case Study from Alto Tietê Region, Brazil †

Abstract

1. Introduction

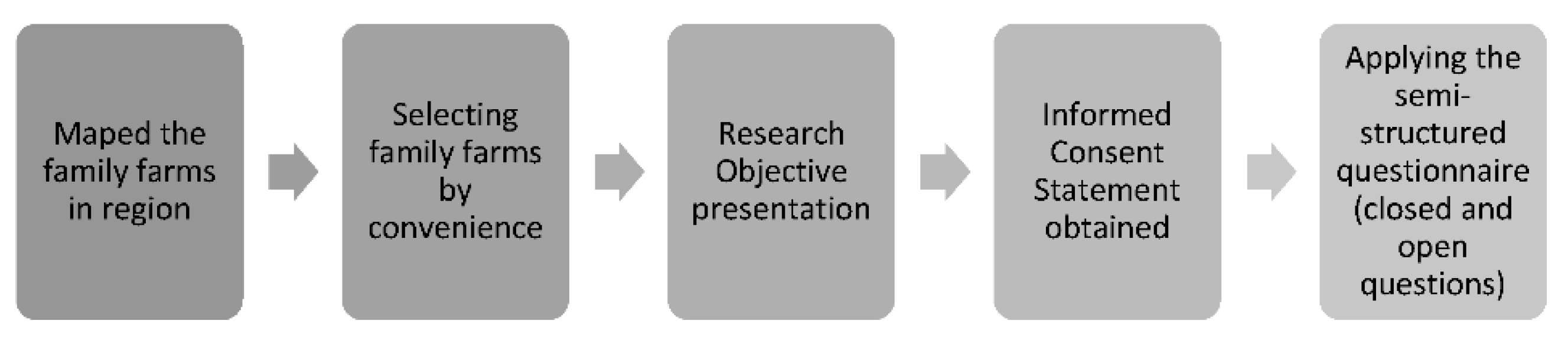

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

3. Results

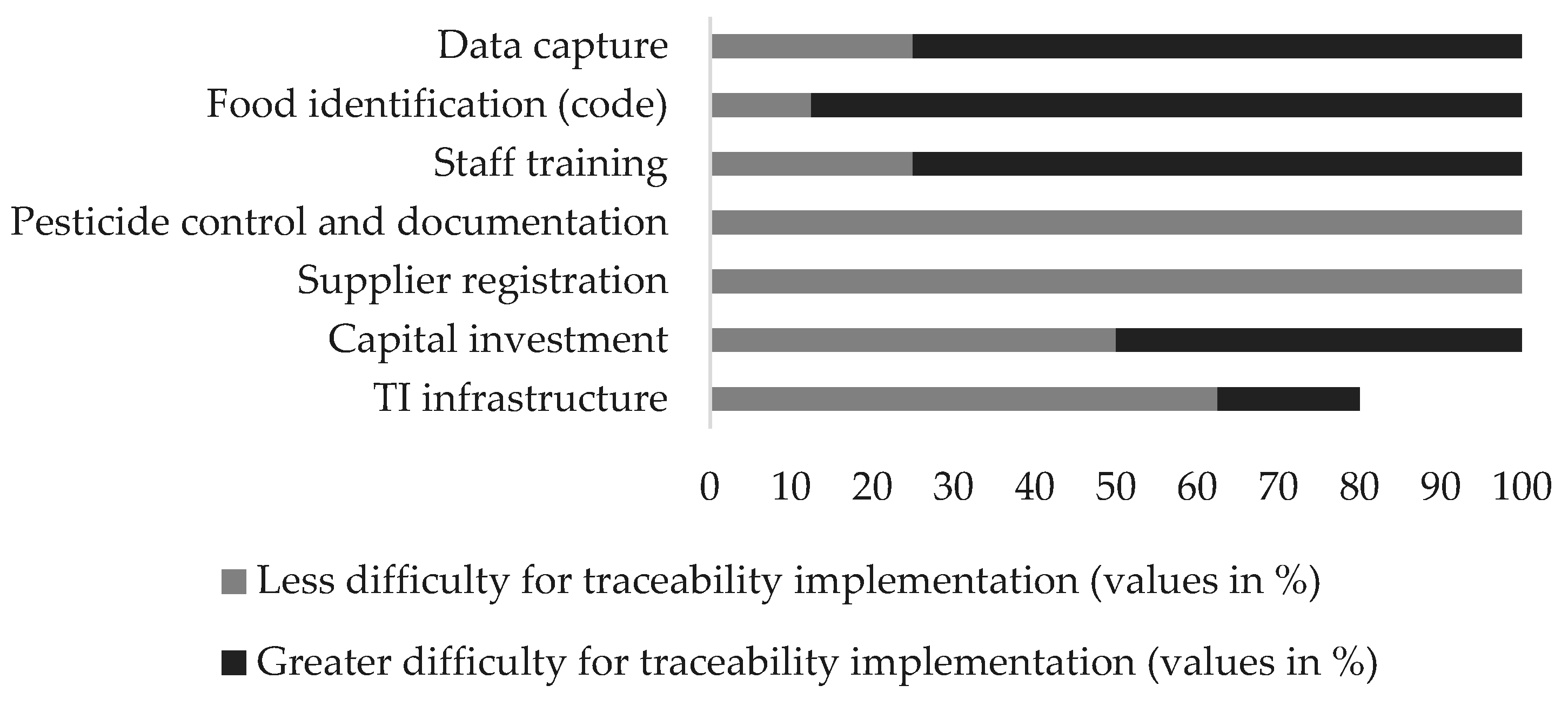

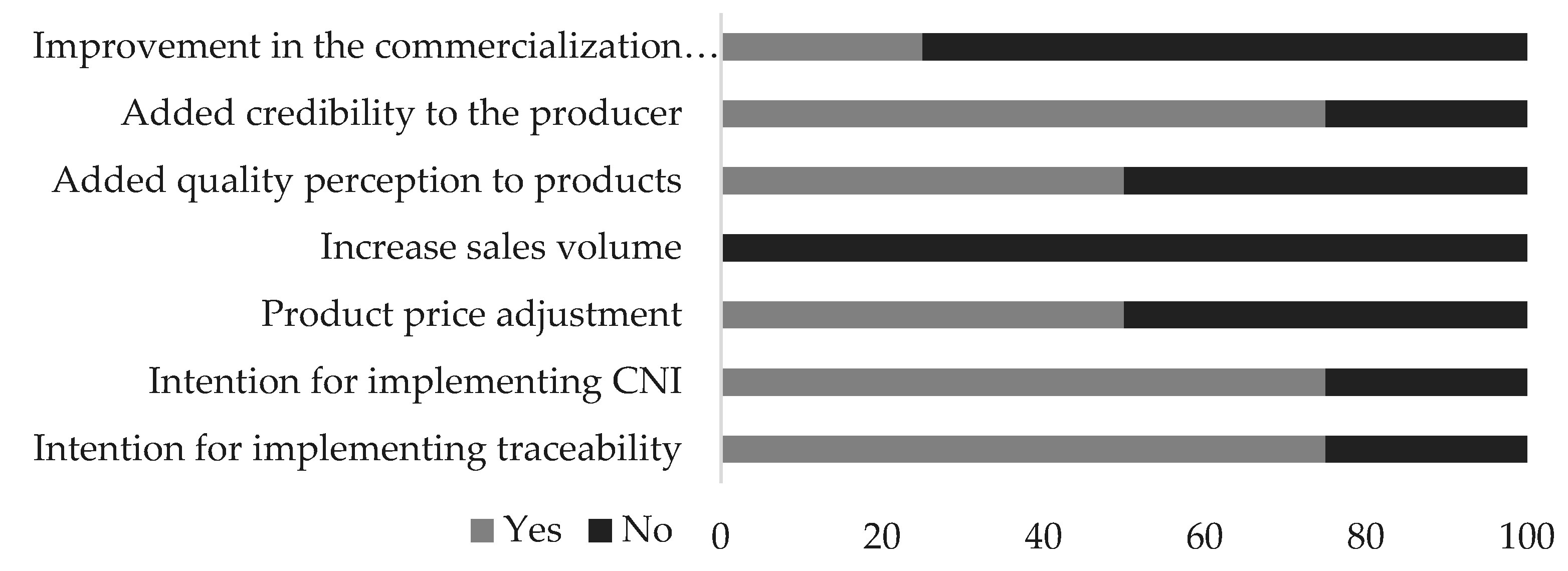

Local Farmers and Traceability System Implementation

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patidar, A.; Sharma, M.; Agrawal, R. Prioritizing drivers to creating traceability in the food supply chain. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.B.; Silva, T.T.C.; Garcia, S.R.M.C.; Srur, A.U.O.S. Estimation of organophosphate pesticide ingestion through intake of fruits and vegetables. Cad. Saúde Coletiva 2018, 26, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvisa, A.N.d.V.S. Instrução Normativa Conjunta No 2, de 7 de Fevereiro de 2018. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/2915263/do1-2018-02-08-instrucao-normativa-conjunta-inc-n-2-de-7-de-fevereiro-de-2018-2915259 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Anvisa, A.N.d.V.S. Instrução Normativa Conjunta No 1, de 15 de Abril de 2019. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/instru%C3%87%C3%83o-normativa-conjunta-n%C2%BA-1-de-15-de-abril-de-2019-86232063 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Available online: https://censos.ibge.gov.br/agro/2017/resultados-censo-agro-2017.html (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Paes, R.S.; Zappes, C.A. Agricultura familiar no norte do estado do rio de janeiro: Identificação de manejo tradicional. Soc. Nat. 2016, 28, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/sp/mogi-das-cruzes/panorama (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Astill, J.; Dara, R.A.; Campbell, M.; Farber, J.M.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Sharif, S.; Yada, R.Y. Transparency in food supply chains: A review of enabling technology solutions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, M.M.; Chang, Y.S. Traceability in a food supply chain: Safety and quality perspectives. Food Control 2014, 39, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávero, L.P.; Belfiore, P. Manual de Análise de Dados, 1st ed.; LTC: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2021; pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Savian, M. Sucessão geracional: Garantindo-se renda continuaremos a ter agricultura familiar? Rev. Espaço Acadêmico 2014, 14, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, W.L.; Fonseca, W.J.L.; Oliveira, A.A.; Vogado, G.M.S.; Sousa, G.G.T.; Sousa, T.O.; Sousa Júnior, S.C.; Luz, C.S.M. Causas e consequências do êxodo rural no nordeste brasileiro. Nucleus 2015, 12, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, A.; Hoffmann, R.; Kageyama, A.; Hoffmann, R. Determinantes da renda e condições de vida das famílias agrícolas no brasil. Economia 2000, 1, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, G.J. Metodologia para Inovação Tecnológica Através de Sistema Colaborativo de Inclusão Digital e Certificação na Agricultura Familiar. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.C.; Santos, C.A.; Menezes, I.R.; Teixeira, L.M.; Costa, J.P.R.; Souza, R.M. Perfil sanitário de unidades agrícolas familiares produtoras de leite cru e adequação à legislação vigente. Ciência Anim. Bras. 2016, 17, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carvalho, F.A. Inclusão Digital: A Influência do Ensino de Informática como Contribuição à Gestão Rural. Bachelor’s Thesis, Fundação Universidade Federal de Rondônia, Rondônia, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Socioeconomics Variables | Highlighted Results | Values in % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 80 |

| Age | Above 46 years old | 55 |

| School | Elementary school | 55 |

| Family income | From 3 to 7 basic salary | 67 |

| Family size | From 3 to 4 people | 55 |

| Legal condition of farmer | Independent farmer | 67 |

| Work experience in years | Above 31 | 55 |

| Production system | Conventional production | 89 |

| People in family working on farm | No, just family members | 67 |

| Farmer Work Experience in Years | Biological | Organic | Chemical |

|---|---|---|---|

| From 11 to 20 | 7.14 | 14.28 | |

| From 21 to 30 | 7.14 | 7.14 | |

| From 31 to 40 | 7.14 | 14.28 | |

| Above 41 | 21.42 | 21.42 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Era, L.; Machado, S.; Kawamoto, L., Jr. Food Supply Chain Traceability: A Multiple Case Study from Alto Tietê Region, Brazil. Chem. Proc. 2022, 10, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/IOCAG2022-12176

Era L, Machado S, Kawamoto L Jr. Food Supply Chain Traceability: A Multiple Case Study from Alto Tietê Region, Brazil. Chemistry Proceedings. 2022; 10(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/IOCAG2022-12176

Chicago/Turabian StyleEra, Lucas, Sivanilza Machado, and Luiz Kawamoto, Jr. 2022. "Food Supply Chain Traceability: A Multiple Case Study from Alto Tietê Region, Brazil" Chemistry Proceedings 10, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/IOCAG2022-12176

APA StyleEra, L., Machado, S., & Kawamoto, L., Jr. (2022). Food Supply Chain Traceability: A Multiple Case Study from Alto Tietê Region, Brazil. Chemistry Proceedings, 10(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/IOCAG2022-12176