1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic, progressive metabolic disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. It has emerged as one of the most significant global health challenges, affecting an estimated 537 million adults worldwide in 2021, with projections to reach 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045 [

1]. The disease contributes substantially to global morbidity and mortality, being a major cause of cardiovascular diseases, neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy, thereby imposing enormous economic and social burdens [

2,

3,

4]. Early detection and timely intervention in the prediabetic or early diabetic stage have been shown to significantly mitigate long-term complications and improve patient outcomes through targeted lifestyle modifications, pharmacological therapy, and preventive care [

5,

6].

Conventional diabetes screening typically relies on clinical and lifestyle indicators such as age, obesity, family history, hypertension, smoking, and diet patterns [

7]. Although such risk scores—such as the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) or the American Diabetes Association (ADA) screening and diagnostic criteria—are simple and widely used in clinical and population-based settings, they often exhibit only moderate sensitivity and specificity, particularly across heterogeneous populations with differing genetic, lifestyle, and environmental backgrounds [

8,

9,

10,

11]. This limitation arises from the multifactorial nature of diabetes, which involves complex interactions among genetic predispositions, metabolic dysregulation, inflammatory processes, and environmental exposures [

12,

13,

14]. Consequently, conventional statistical models may inadequately capture nonlinear relationships and higher-order interactions critical to disease onset, thereby reducing predictive robustness and transferability [

15].

Recent advancements in Machine Learning (ML) have opened new avenues for developing accurate, data-driven diabetes risk prediction models. ML algorithms—such as Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Deep Neural Networks (DNN)—excel in identifying subtle and nonlinear interactions among high-dimensional features, outperforming conventional logistic regression and regression tree models in various medical contexts [

16,

17,

18]. Studies have demonstrated the utility of ML for both type 2 diabetes onset prediction [

19], early-stage detection [

20], and risk stratification based on lifestyle, metabolic, and biochemical indicators [

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, interpretable ML frameworks incorporating explainability metrics such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and feature importance analysis have facilitated better clinical translation and trustworthiness in model deployment [

24].

Despite these advances, ensuring robustness, stability, and generalizability remains a methodological challenge in clinical ML research. Overfitting and data imbalance can lead to inflated performance in internal validation yet poor generalization on external datasets [

25]. To overcome this, feature selection techniques play a vital role in model interpretability and reproducibility. The Union Feature Selection approach, which aggregates results from multiple selection methods (e.g., LASSO, mutual information, tree-based importance), has been shown to improve feature stability, reduce bias, and enhance cross-dataset consistency [

26,

27,

28]. Complementarily, External Validation—using independent real-world datasets—provides the most stringent assessment of a model’s generalizability, a step increasingly emphasized by the TRIPOD and PROBAST guidelines for clinical prediction models [

29,

30,

31]. Recent advances in machine learning for tabular data further highlight the importance of rigorous external evaluation, as performance gains observed in complex models may not consistently translate to unseen clinical datasets without careful validation and feature interpretability considerations [

32].

Previous studies on diabetes risk prediction have predominantly focused on optimizing predictive accuracy using individual machine learning algorithms or single feature-selection techniques. Many approaches rely on complex ensemble models or high-dimensional feature spaces, which often yield excellent internal validation performance but suffer from limited interpretability and reduced generalizability when applied to external clinical datasets. In addition, several studies evaluate model performance exclusively on a single dataset, without independent external validation, thereby increasing the risk of overfitting and optimistic bias.

In contrast, the present study adopts a methodologically distinct strategy by explicitly integrating statistical significance testing with complementary machine learning–based feature selection methods to enhance feature stability and clinical interpretability. Moreover, the proposed framework places strong emphasis on external validation using independent real-world hospital data, allowing direct assessment of model robustness under distributional shifts. This methodological design addresses key limitations of prior approaches and provides a more realistic evaluation of screening performance in practical clinical and community settings.

Therefore, the present study aims to develop and externally validate a robust ML framework for early-stage diabetes risk screening by combining the publicly available UCI Early Stage Diabetes Risk Prediction dataset with retrospective hospital data from the University of Phayao Hospital. By employing Union Feature Selection and cross-domain validation, this study seeks to build a model that is not only accurate but also interpretable and clinically applicable, supporting evidence-based decision-making for diabetes prevention and management in both community and hospital settings.

In contrast to recent collaborative or federated learning approaches that primarily focus on improving feature representation across large, distributed, and heterogeneous datasets, the proposed framework emphasizes feature stability, interpretability, and real-world generalizability for early-stage diabetes screening. While collaborative learning methods are powerful in data-rich environments, they often require substantial infrastructure, complex model aggregation, and may sacrifice feature-level transparency. In this study, the union feature-selection strategy integrates statistical significance with complementary machine learning–based importance measures to identify robust and clinically meaningful predictors that remain stable across datasets. Combined with external validation using independent hospital records, this approach demonstrates strong robustness and practical applicability for early-stage screening in real-world clinical and community settings, where data availability is limited and interpretability is essential.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a retrospective analytical design integrating a publicly available dataset with real-world clinical data to develop and validate machine learning models for early-stage diabetes risk screening. The statistical and preliminary analyses were conducted using amovi version 2.7 and R version 4.5, ensuring transparent and reproducible workflows [

33,

34,

35].

2.2. Dataset Description

The primary dataset used for initial modeling was the UCI Early Stage Diabetes Risk Prediction Dataset [

36], which consists of 520 individual records. Each record includes 17 predictor variables related to demographic, clinical, and lifestyle factors, and one binary outcome variable representing the presence (“Positive”, n = 320) or absence (“Negative”, n = 200) of early-stage diabetes. Although the dataset is not perfectly balanced, the class distribution remains within an acceptable range for supervised learning and was handled consistently across all analyses. The variables cover a wide range of symptoms and risk indicators, including age, gender, polyuria, polydipsia, sudden weight loss, weakness, polyphagia, genital thrush, visual blurring, itching, irritability, delayed healing, partial paresis, muscle stiffness, alopecia, and obesity.

All categorical variables were systematically transformed into binary numerical representations to ensure consistency across statistical analyses and machine learning models, while the age variable was retained in its original continuous numerical form. A unified encoding scheme was applied to both datasets, as summarized in

Table 1, with no missing values observed in any variables.

In addition, retrospective hospital records were obtained from the University of Phayao Hospital between 2023 and 2025 to serve as an external validation cohort. This dataset comprised 60 anonymized patient records, including 30 individuals clinically diagnosed with early-stage diabetes and 30 non-diabetic controls matched by age and sex where possible. Extracted variables encompassed demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking and alcohol use), medical history, and laboratory findings consistent with the predictors used in the UCI dataset. All patient identifiers were removed prior to analysis to ensure compliance with ethical standards and institutional data protection policies.

In this study, early-stage diabetes was defined as individuals who were newly diagnosed based on standard laboratory criteria at their first clinical detection and had not yet received any pharmacological or lifestyle treatment. Importantly, the proposed machine learning models were not designed to replace laboratory diagnosis. Instead, they function as symptom-based screening tools that utilize readily available demographic and clinical symptom information to identify individuals likely to be in this early diagnostic window prior to treatment initiation.

2.3. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical feature extraction was performed as an initial step to characterize predictor distributions and statistical relevance prior to machine learning model development, using jamovi (version 2.7) to ensure transparency and reproducibility. For continuous variables, summary statistics and the Shapiro–Wilk test were applied to assess central tendency, variability, and normality. For categorical variables, group-wise frequencies and chi-square tests were used to evaluate associations with the outcome. Multicollinearity was assessed via variance inflation factors (VIFs) derived from logistic regression, with all predictors showing acceptable VIF values. These statistical insights informed clinically meaningful feature identification, subsequent machine learning–based feature ranking, and the construction of compact, interpretable feature subsets.

2.3.1. Age Distribution

Sample size (N): 520.

Mean ± SD: 48.0 ± 12.2 years.

Median: 47.5 years.

Range: 16–90 years.

Skewness: 0.329 (slightly right-skewed).

Kurtosis: −0.192 (approximately mesokurtic).

Normality test (Shapiro–Wilk): W = 0.983, p < 0.001, indicating deviation from a normal distribution.

2.3.2. Categorical Variables

The frequency analysis indicated that most clinical symptoms had unequal class distributions between diabetic (“Positive”) and non-diabetic (“Negative”) groups:

Table 2 presents the most frequent category, corresponding percentages, and statistical associations with diabetes classification derived from the binomial logistic regression model. Variables such as polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, genital thrush, irritability, and partial paresis were identified as significant predictors (

p < 0.05), whereas delayed healing, alopecia, and obesity showed no significant associations (

p > 0.05). These results indicate that polyuria, polydipsia, irritability, genital thrush, polyphagia, and partial paresis were key differentiating features between diabetic and non-diabetic individuals.

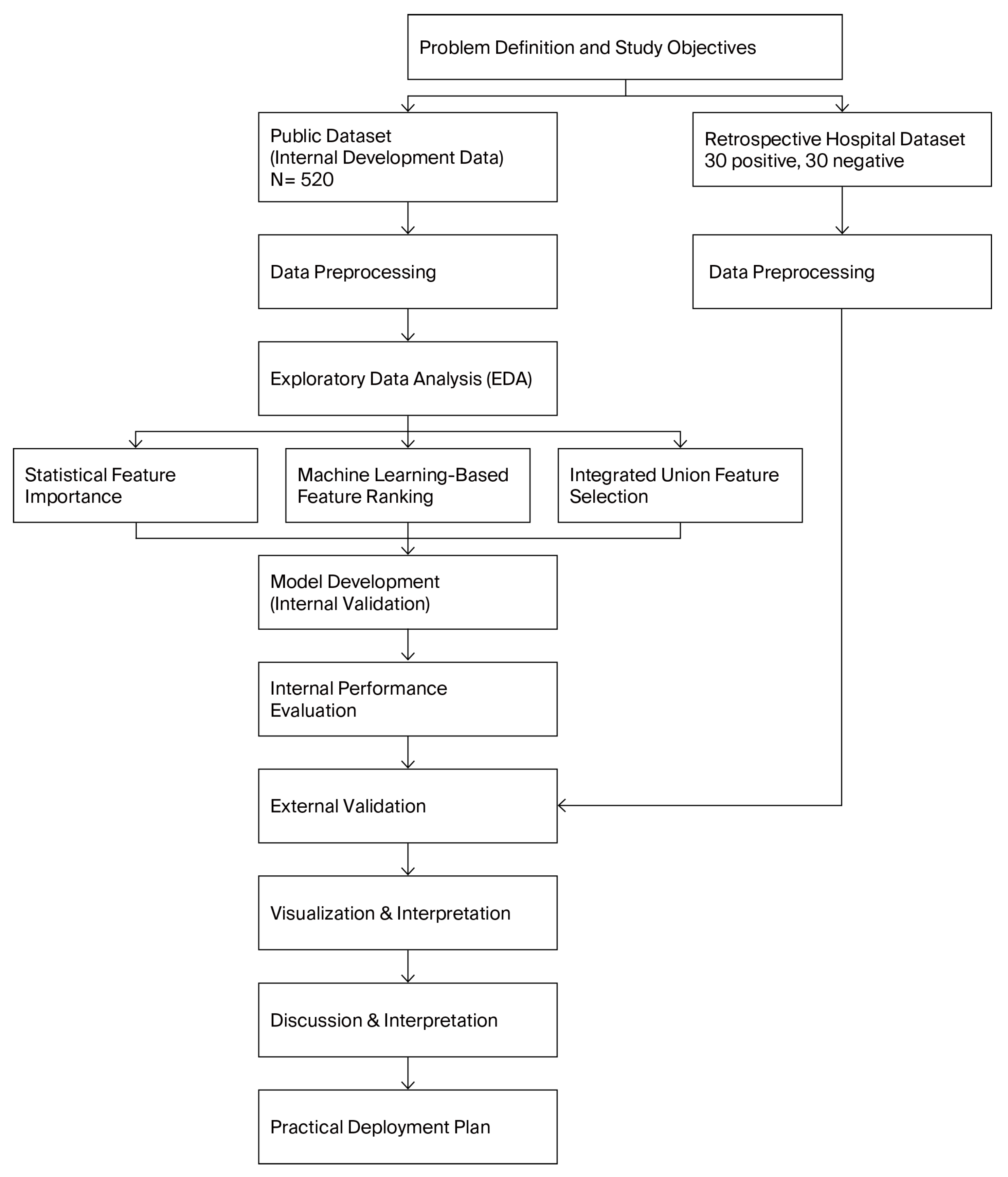

2.4. Workflow

From

Figure 1, the research workflow begins with defining the study objectives and collecting two datasets: a public early-stage diabetes dataset (N = 520) for model development and a retrospective hospital dataset (30 positive, 30 negative) for external validation. After data preprocessing, exploratory data analysis (EDA) is performed to understand variable distributions and clinical patterns.

Feature selection is conducted through three complementary approaches—statistical significance testing, machine-learning–based feature ranking, and an integrated union feature-selection strategy—to identify the most informative predictors. These selected features are used to develop and internally validate multiple machine learning models.

Internal performance evaluation identifies the best-performing algorithms, which are then further assessed using the external hospital dataset to evaluate real-world generalizability. The results are visualized and interpreted through confusion matrices, ROC curves, and model comparisons. Finally, insights from the analyses inform the discussion, interpretation, and formulation of a practical deployment plan for real-world early-stage diabetes screening.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Statistical Analysis of Predictors

The model includes 17 predictors covering demographic, clinical, and symptomatic variables. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) represent the likelihood of being classified as “Positive” for early-stage diabetes.

Significant predictors are defined at p < 0.05.

Following the initial full-model analysis in

Table 3, non-significant predictors were systematically removed to improve parsimony and model interpretability. Four reduced logistic regression models were compared:

- (1)

Reduced model excluding Gender;

- (2)

Reduced model including only significant predictors;

- (3)

Reduced model with additional refinement on Itching and interaction terms;

- (4)

Reduced model excluding weakly correlated variables.

From

Table 4, the best-performing reduced model (AIC = 200, AUC = 0.980) retained nine predictors—Age, Gender, Polyuria, Polydipsia, Polyphagia, Genital thrush, Itching, Irritability, and Partial paresis—which collectively yielded excellent predictive accuracy and generalizability. This outcome suggests that most of the discriminative power can be maintained even after removing non-significant or redundant variables, thereby improving the interpretability and clinical applicability of the model for early-stage diabetes screening.

3.2. Feature Selection and Model Development Using Machine Learning

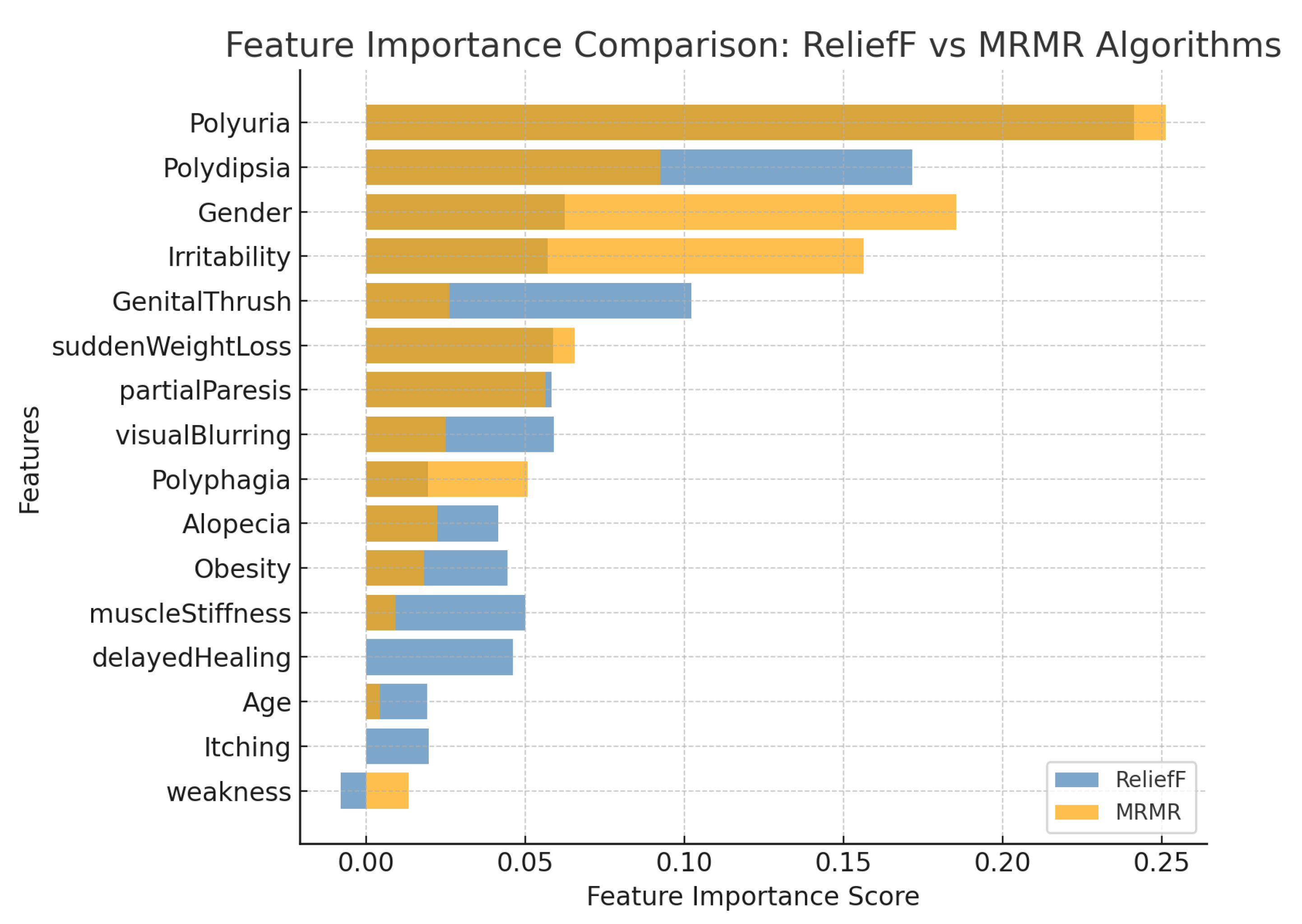

To identify the most relevant and stable predictors for early-stage diabetes classification, two complementary feature selection algorithms—ReliefF and Minimum Redundancy–Maximum Relevance (MRMR)—were employed. The ReliefF algorithm evaluates each feature based on its ability to differentiate between neighboring instances of different outcome classes, effectively capturing local interactions and non-linear relationships among variables. In contrast, the MRMR algorithm optimizes feature selection by maximizing the relevance of each variable to the target class while minimizing redundancy among correlated predictors, thereby improving model interpretability and generalizability. By integrating the strengths of both methods, the study aimed to enhance feature stability, reduce multicollinearity, and identify the most discriminative subset of predictors for subsequent model development.

From

Figure 2 and

Table 5, the comparative analysis between the ReliefF and MRMR algorithms revealed both consistency and complementarity in identifying the most relevant predictors for early-stage diabetes classification.

Both algorithms consistently identified polyuria and polydipsia as the top-ranked predictors, with average importance scores of 0.246 and 0.132, respectively, confirming their strong association with early hyperglycemic symptoms.

Gender (0.124) and irritability (0.107) were also highly ranked, particularly under the MRMR algorithm, emphasizing the demographic and behavioral diversity influencing diabetes risk.

Clinical symptoms such as genital thrush (0.064), sudden weight loss (0.062), partial paresis (0.057), and visual blurring (0.042) were moderately important, indicating potential secondary manifestations of metabolic dysregulation.

Features with lower averaged relevance, including polyphagia, alopecia, obesity, muscle stiffness, delayed healing, age, itching, and weakness, exhibited limited discriminative power and may be excluded in model refinement phases to enhance generalizability.

Overall, the integration of ReliefF and MRMR results strengthened feature stability by combining local relevance detection (ReliefF) with redundancy minimization (MRMR).

Table 6, each case corresponds to a different feature inclusion threshold (Case 1 > 0.04, Case 2 > 0.03, Case 3 > 0.02, and Case 4 = all features).

Table 7, all models achieved high accuracy (≥90%). The Naive Bayes and SVM consistently performed best, with SVM in Case 3 (97.31%) offering the optimal balance between accuracy and training time, while Naive Bayes in Case 4 (97.69%) reached the highest overall accuracy but required longer computation.

3.3. Union Feature Selection and Integrated Model Construction

Table 8 summarizes the integrated ranking of all candidate features using a combined approach that incorporates both statistical significance and machine learning–based feature importance. Specifically, the ranking was derived by jointly evaluating:

Statistical evidence from logistic regression (p-value and Odds Ratio), representing clinical relevance and strength of association; and

Machine learning importance from the ReliefF and MRMR algorithms, capturing nonlinear interactions and redundancy-adjusted relevance.

A composite score was generated to reflect each variable’s overall predictive value, thereby supporting a robust and interpretable Union Feature Selection framework for early-stage diabetes risk classification.

Using the combined scoring formula, defined as Combined Score = 0.5(1 − p) + 0.5 (Average ML Score), the integrated ranking identified polyuria, polydipsia, gender, and irritability as the most influential predictors. These variables consistently exhibited strong statistical significance alongside high machine learning importance. Collectively, they reflect classical early manifestations of hyperglycemia and key patient-level characteristics known to affect metabolic risk. A second tier of moderately important features—including genital thrush, partial paresis, and polyphagia—showed either statistical significance or meaningful machine learning scores, indicating their supportive role in improving model discrimination, particularly in nonlinear classifiers.

Several features such as muscle stiffness, visual blurring, age, and itching exhibited moderate combined scores. Although not always statistically significant, their machine learning contributions suggest potential value in capturing subtle behavioral or physiological patterns.

Conversely, variables such as obesity, alopecia, delayed healing, and weakness ranked lowest in combined importance and demonstrated limited discriminative power. These features may still be useful in specific clinical contexts but provide minimal incremental benefit for automated screening models.

Overall, the combined statistical–machine learning ranking supports a parsimonious feature set centered on the most influential predictors while maintaining flexibility to incorporate moderate-level variables depending on model objectives and computational constraints. This integrated feature selection strategy enhances both model interpretability and predictive robustness for early-stage diabetes risk assessment.

To enable a structured comparison of predictive performance under varying levels of model complexity, three feature-selection scenarios were defined based on the integrated importance ranking:

Scenario 1: Core highly influential features.

This scenario included only the most influential predictors, namely polyuria, polydipsia, gender, and irritability. These variables represent the strongest combined signals across both statistical and machine-learning evaluation and serve as the foundational feature set for a minimal yet high-impact screening model.

Scenario 2: Core features plus secondary-importance predictors.

In this configuration, the core influential features were combined with secondary-importance variables, including genital thrush and partial paresis. This expanded set was designed to determine whether moderately strong predictors contribute additional discriminatory power beyond the core model.

Scenario 3: Comprehensive model including moderate-importance features.

The final cenario incorporated the core, secondary, and moderate-importance features, adding polyphagia, muscle stiffness, visual blurring, age, and itching. This comprehensive feature set aimed to evaluate the upper bound of model performance when broader physiological and demographic indicators are included.

Table 9 presents the training time, validation accuracy, and test-set performance—including precision, recall, and F1-score—of five machine learning models (Decision Tree, Naïve Bayes, SVM, KNN, and Neural Network). Three scenarios were evaluated, each corresponding to a different subset of features ranked by machine learning–based feature importance. Scenario 3, which incorporated the most informative feature subset, yielded the highest predictive performance across multiple classifiers, with SVM, KNN, and Neural Network achieving accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores exceeding 96%.

3.4. External Validation Using Retrospective Hospital Records

To further evaluate the generalizability of the developed machine learning models, an external validation was conducted using retrospective hospital records. In this section, feature subsets were constructed based solely on machine learning–based feature importance rankings derived from the internal training dataset. Five distinct feature-selection cases were generated to investigate how different combinations of top-ranked features influence predictive performance when applied to real-world clinical data. The selected models were then evaluated on an independent hospital dataset to assess their robustness against distributional shifts and their ability to retain discriminative capability outside the training environment.

Because all diabetic cases in the external validation cohort represented newly diagnosed and untreated individuals, the performance metrics reported in this section specifically reflect the ability of the proposed models to screen for early-stage diabetes, rather than to predict established or treated disease.

3.4.1. Machine Learning–Based Feature Importance

From

Table 10, the table reports the performance of five classifiers—Decision Tree, Naïve Bayes, SVM, KNN, and Neural Network—evaluated using hospital retrospective records. Five ML-based feature selection cases were tested to assess the influence of different feature subsets on model generalization. Performance metrics include validation accuracy, test accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Naïve Bayes consistently provided the strongest balance between validation and test performance, achieving the highest overall stability across all cases.

Beyond conventional accuracy-based metrics, additional imbalance-aware evaluations further clarified the relative robustness of the examined models under external validation. In particular, Naïve Bayes consistently achieved the highest balanced accuracy across all five feature selection cases, with values ranging from approximately 81.7% to 83.8%. This indicates stable sensitivity to both diabetic and non-diabetic classes when applied to unseen hospital data.

Moreover, Naïve Bayes yielded the strongest Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), with values between 0.636 and 0.673, substantially outperforming the other classifiers. These results reflect a high level of agreement between predicted and true class labels beyond random chance. In contrast, Decision Tree and Neural Network models exhibited markedly lower balanced accuracy (typically below 66%) and weak MCC values (≤0.315), despite showing high validation accuracy. SVM and KNN demonstrated moderate and case-dependent improvements in balanced accuracy; however, their MCC values remained consistently inferior to those of Naïve Bayes, suggesting less reliable overall classification performance across different feature subsets.

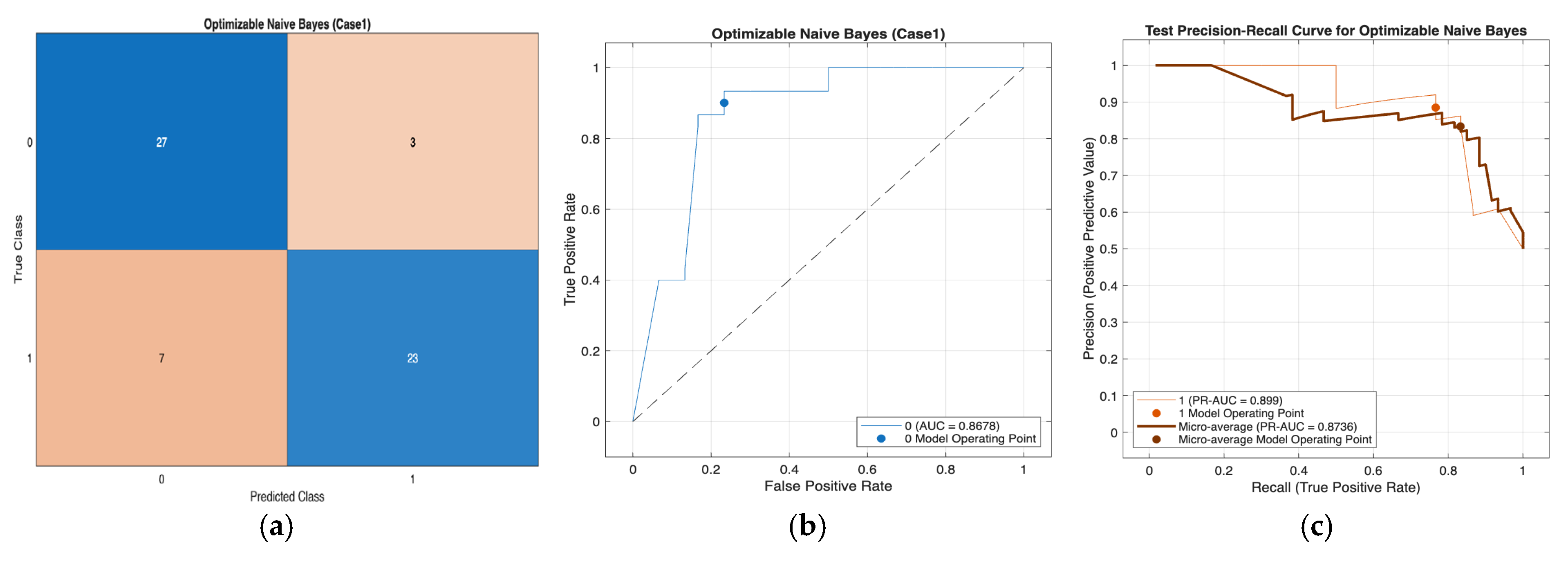

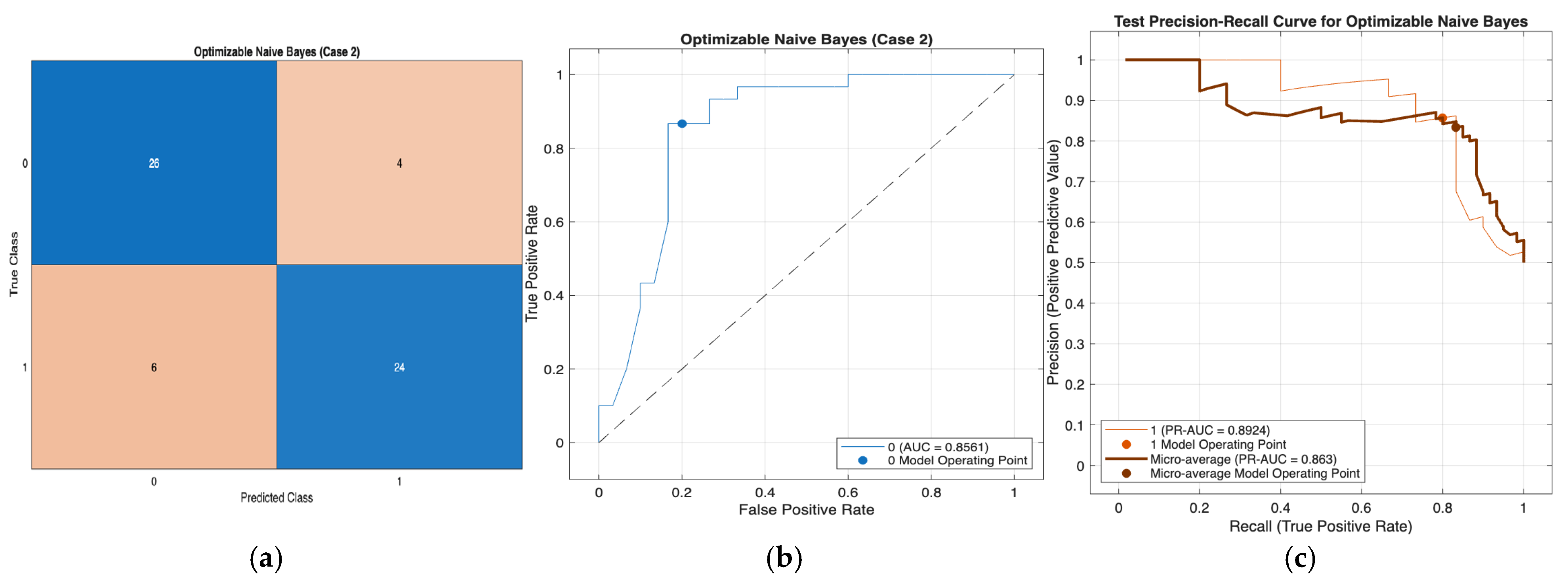

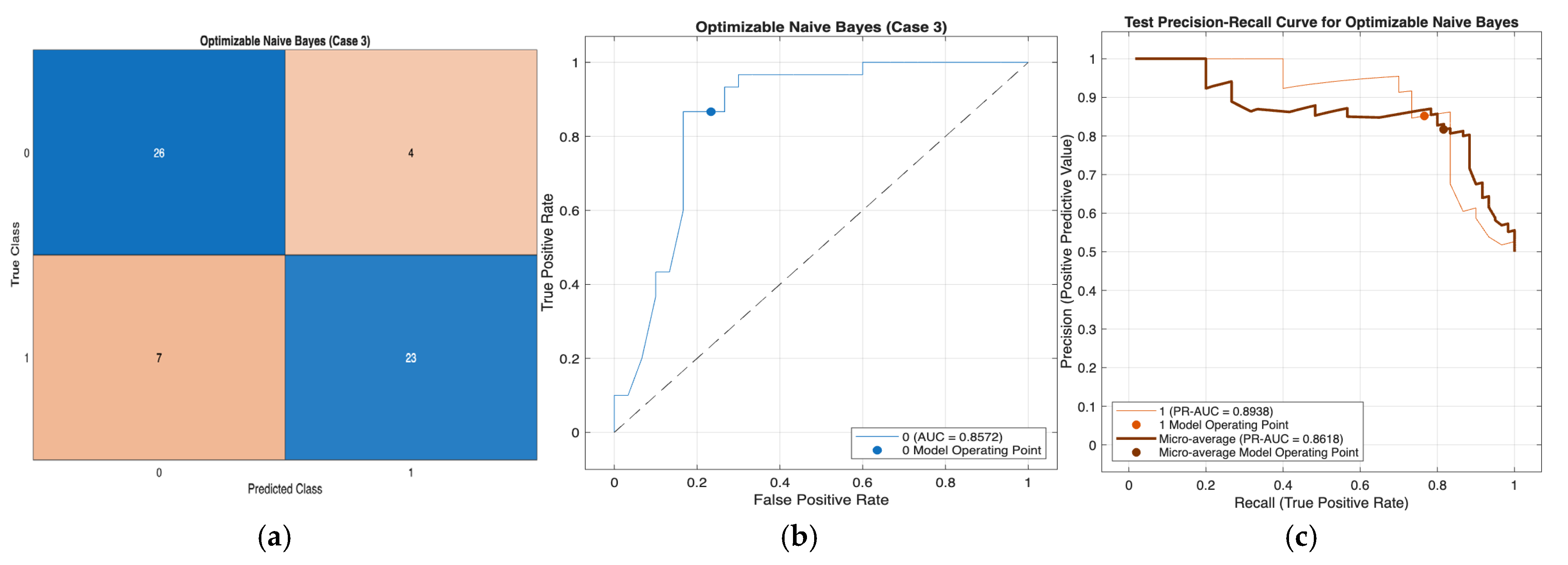

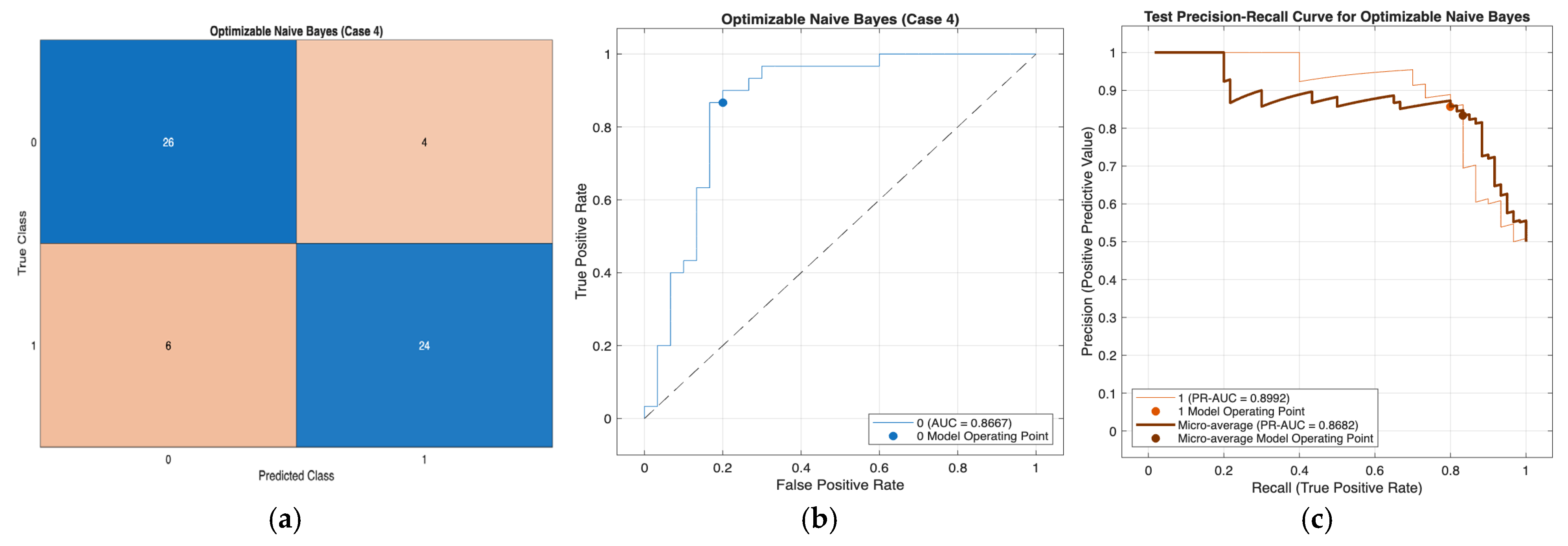

Across Cases 1–4, the Optimizable Naïve Bayes model consistently demonstrated strong and stable classification performance, correctly classifying approximately 50 out of 60 retrospective hospital records in each case. The confusion matrices indicate a balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, with reliable detection of diabetic cases and effective exclusion of non-diabetic individuals across varying feature subsets. The ROC analyses further confirm robust discriminative ability, with AUC values ranging from 0.856 to 0.868 across all four cases, reflecting consistent separation between positive and negative classes. In addition, the precision–recall curves exhibit favorable precision–recall trade-offs under class imbalance, indicating that high precision is maintained even at increased recall levels. Collectively, these results demonstrate the robustness and generalizability of the Optimizable Naïve Bayes model across different feature configurations, supporting its suitability as a reliable screening model for early-stage diabetes using real-world hospital data.

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 present a comprehensive performance evaluation of the Optimizable Naïve Bayes model across the four experimental cases, including confusion matrices, ROC curves, and precision–recall (PR) curves.

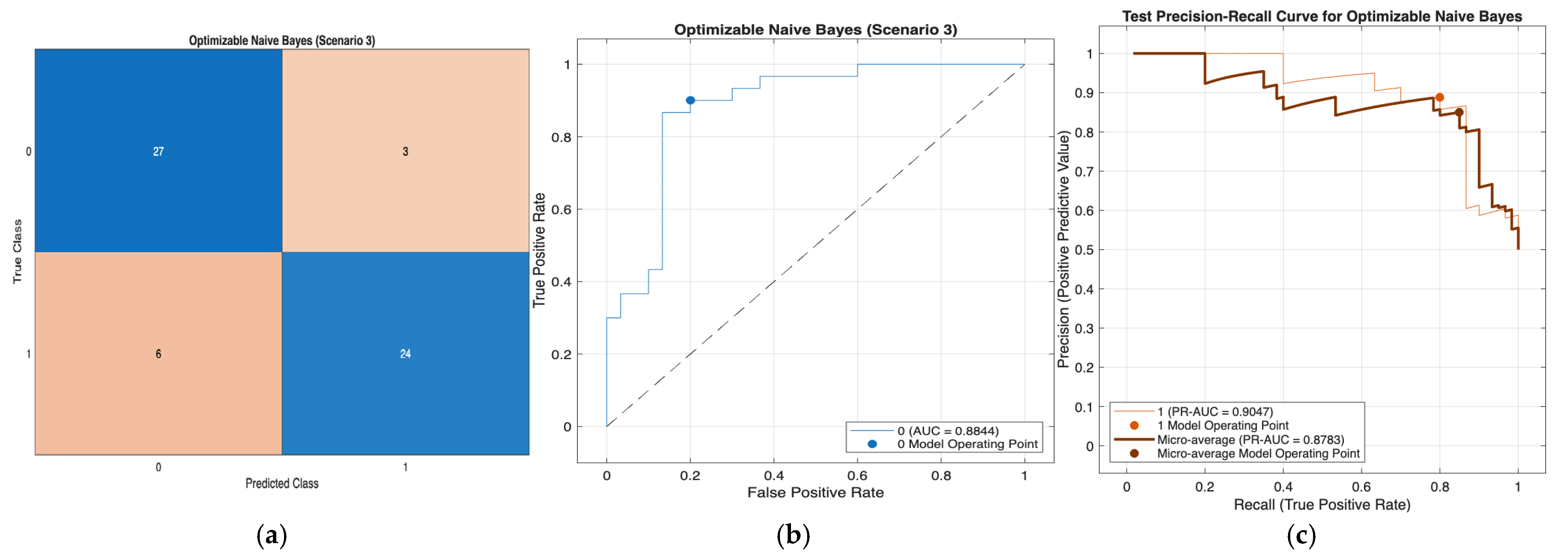

3.4.2. Union Feature Selection (Statistical and Machine Learning–Based Feature Importance)

Table 11 presents the predictive performance of five machine learning classifiers—Decision Tree, Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Neural Network—evaluated using retrospective hospital records. Three feature-selection scenarios were assessed: Scenario 1 (core highly influential features), Scenario 2 (core + secondary features), and Scenario 3 (core + secondary + moderate features). Performance metrics include validation accuracy, test accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Naïve Bayes consistently achieved the highest test accuracy (85%) and demonstrated the most stable precision, recall, and F1 score across all scenarios.

Beyond standard accuracy-based evaluation, the imbalance-aware metrics in

Table 11 further emphasize the robustness of the screening models under external validation. Across all three feature-selection scenarios, Naïve Bayes consistently achieved the highest balanced accuracy (85.0%) and the strongest Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC = 0.703), indicating reliable discrimination between diabetic and non-diabetic classes.

In contrast, Decision Tree, SVM, KNN, and Neural Network models exhibited noticeably lower balanced accuracy, ranging from approximately 60.0% to 70.0%, with corresponding MCC values remaining below 0.41. Although some models, particularly Decision Tree in Scenario 3, demonstrated moderate improvements in balanced accuracy, their overall agreement between predicted and true labels was substantially weaker than that of Naïve Bayes. These results confirm the superior and stable generalization performance of Naïve Bayes across all union-based feature selection scenarios.

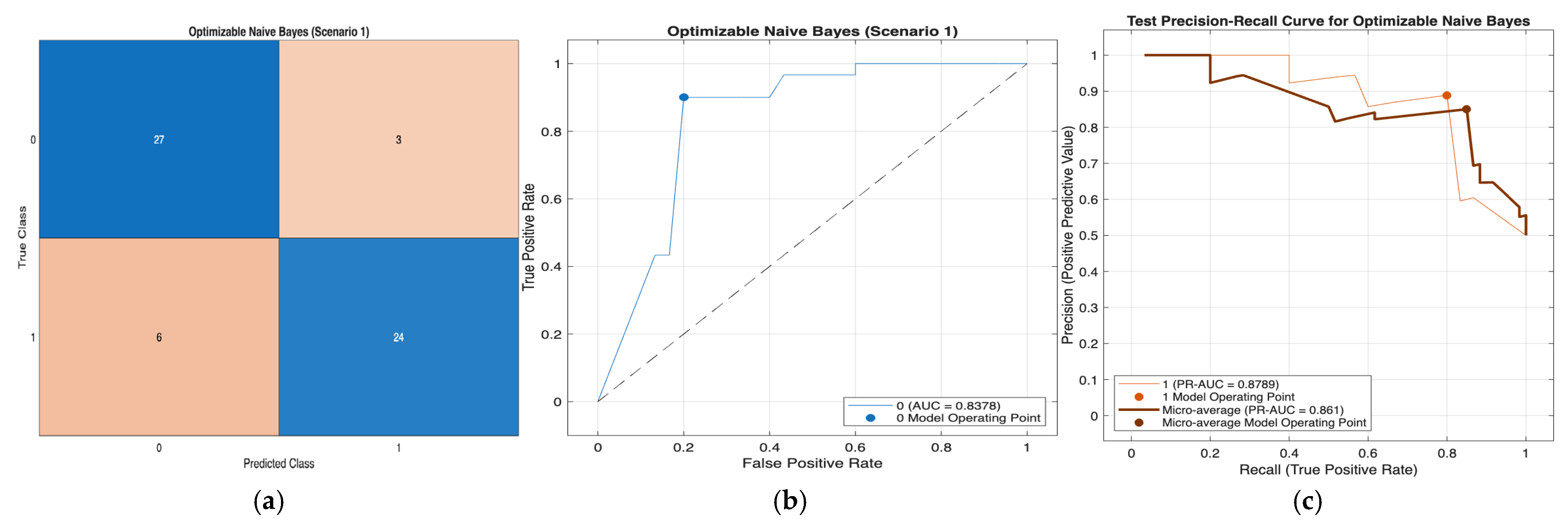

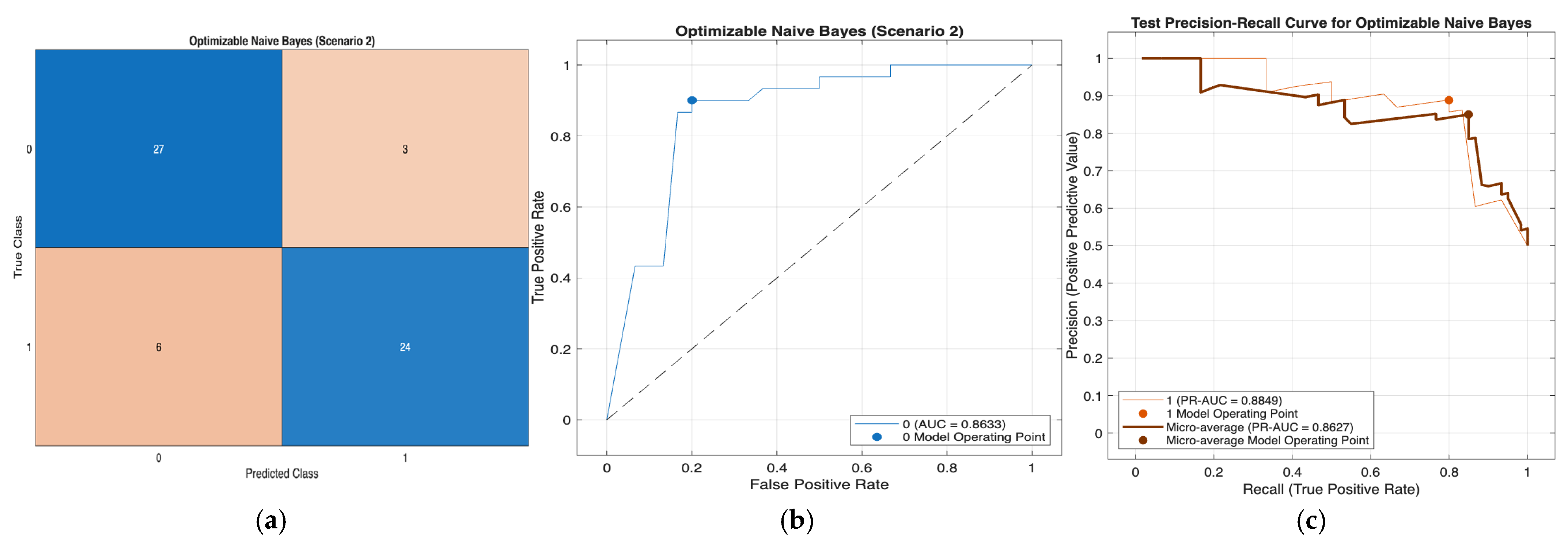

Across all three scenarios, the Optimizable Naïve Bayes model demonstrated consistently strong and stable performance for early-stage diabetes classification using retrospective hospital records, as illustrated in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. The confusion matrices indicate balanced sensitivity and specificity, while ROC and precision–recall analyses confirm robust discriminative ability under class imbalance, with AUC values exceeding 0.83 in all scenarios. Model performance improved progressively from Scenario 1 to Scenario 3 as additional statistically and machine-learning–selected features were incorporated, supporting the effectiveness of the union feature-selection strategy. Nevertheless, Scenario 1 achieved competitive results with a reduced feature set, highlighting the strong discriminative power of core predictors. Overall, these findings demonstrate the strong generalizability and practical suitability of the Optimizable Naïve Bayes model for real-world early-stage diabetes screening and its potential integration into clinical decision-support workflows.

4. Discussion

The comparative evaluation between the full logistic regression model and multiple reduced variants offers important insights into the relative contribution of demographic and symptomatic factors to early-stage diabetes prediction. The full model, consisting of 17 predictors, demonstrated outstanding discriminative ability (AUC = 0.982), reinforcing that the combined effects of clinical, behavioral, and demographic factors effectively capture early pathophysiological changes associated with diabetes onset.

It is important to emphasize that the proposed framework is intended for early-stage diabetes screening rather than definitive diagnosis. While laboratory testing remains the diagnostic gold standard, symptom-based machine learning screening may support early identification of individuals in the initial diagnostic phase, thereby enabling timely confirmatory testing and early intervention before treatment initiation.

After systematic feature reduction, several reduced models retained strong predictive capability, indicating that some predictors contribute more substantially than others. Removing gender resulted in a modest decrease in AUC (0.956), suggesting that sex-related biological or behavioral differences play a meaningful role in risk stratification within this population. Conversely, the reduced model containing only statistically significant predictors achieved near-equivalent performance (AUC = 0.980) while improving accuracy (93.8%) and maintaining balanced sensitivity (0.947) and specificity (0.930). These results emphasize that a simplified model can preserve predictive strength while improving interpretability and mitigating overfitting.

Across analyses, polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, genital thrush, irritability, partial paresis, age, and gender consistently emerged as influential predictors. These observations align with existing evidence that excessive urination and thirst are early indicators of glycemic dysregulation, while irritability and generalized weakness reflect metabolic instability. The inverse trend observed for itching suggests potential symptom overlap with non-diabetic dermatologic conditions, meriting further clinical investigation.

Methodologically, the union feature-selection framework—integrating logistic regression significance with machine-learning–based importance (ReliefF and MRMR)—proved highly effective. This approach enhanced model robustness by removing redundant or low-impact variables while preserving features with strong statistical and predictive relevance. Such parsimony is especially valuable when transitioning to machine-learning pipelines, where excessive dimensionality can degrade generalization during external validation.

All reduced logistic models achieved AUC values above 0.94, demonstrating high stability even after substantial feature pruning. This highlights the feasibility of designing lightweight yet accurate screening tools suitable for primary care and community settings where comprehensive data collection may be impractical.

The machine-learning experiments further reinforced these findings. Across four feature-selection scenarios, all models achieved high internal accuracy (≥90%) with balanced micro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-scores. SVM and KNN consistently yielded top performance, with SVM achieving the highest accuracy (97.69%) using all features, while KNN (Case 3) offered an efficient balance between accuracy (97.31%) and computational cost. Neural networks performed strongly but required substantial training time, whereas Decision Tree and Efficient Linear models provided interpretable alternatives with slightly lower accuracy.

Importantly, reducing features did not substantially degrade performance, confirming the effectiveness of the union selection framework in isolating core predictive variables. This finding suggests that simplified models can still achieve high diagnostic accuracy while improving feasibility for real-world deployment.

External validation with retrospective hospital records further underscored this point. Among all algorithms, Naïve Bayes consistently demonstrated the strongest generalization across all scenarios, maintaining test accuracy above 83% with balanced precision, recall, and F1-scores. This finding is consistent with previous diabetes screening studies reporting that Naïve Bayes performs competitively—or even outperforms more complex models—when applied to tabular clinical data, particularly under limited sample sizes and class imbalance conditions [

15,

37].

Notably, increasing the number of features did not yield additional performance gains, suggesting that a compact subset of clinically meaningful predictors is sufficient for practical early-stage diabetes screening. Similar observations have been reported in prior ML-based screening research, where simpler probabilistic models preserved robustness and interpretability while avoiding overfitting [

32,

37]. In contrast, models such as SVM, KNN, and neural networks exhibited decreased performance on external hospital data, indicating sensitivity to dataset shift and reduced transferability, despite strong internal validation results. This behavior aligns with recent findings that complex tabular models may overfit benchmark datasets and fail to generalize without rigorous external validation [

32].

The superior performance of Naïve Bayes in terms of balanced accuracy and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) underscores its robustness under class imbalance and external validation conditions. Unlike accuracy alone, these imbalance-aware metrics provide a more clinically meaningful evaluation by accounting for both false-positive and false-negative predictions. The consistently high balanced accuracy and MCC values indicate strong predictive agreement beyond chance, even as feature subsets vary or expand across different scenarios.

In contrast, the discrepancy between high validation accuracy and poor imbalance-aware performance observed in Decision Tree and Neural Network models suggests potential overfitting and bias toward the majority class. Although SVM and KNN benefited from specific feature configurations, their performance stability remained inferior to that of Naïve Bayes, particularly when evaluated using MCC. Collectively, these findings reinforce Naïve Bayes as a reliable, stable, and interpretable baseline screening model for early-stage diabetes risk assessment using retrospective hospital datasets, especially in real-world clinical environments where feature heterogeneity and class imbalance are common.

Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of model simplicity, generalizability, and clinical interpretability when designing practical screening systems. The union feature-selection strategy, combined with external validation, provides a robust framework for identifying reliable predictors and ensuring model stability across populations. The results indicate that Naïve Bayes, KNN (Case 3), and SVM (Case 4) represent promising candidates for real-world deployment in hospital and community-based early diabetes risk assessment.