The Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Diabetes and Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from the National Spanish Registry Sumamos-FA-SEMI

Abstract

1. Introduction

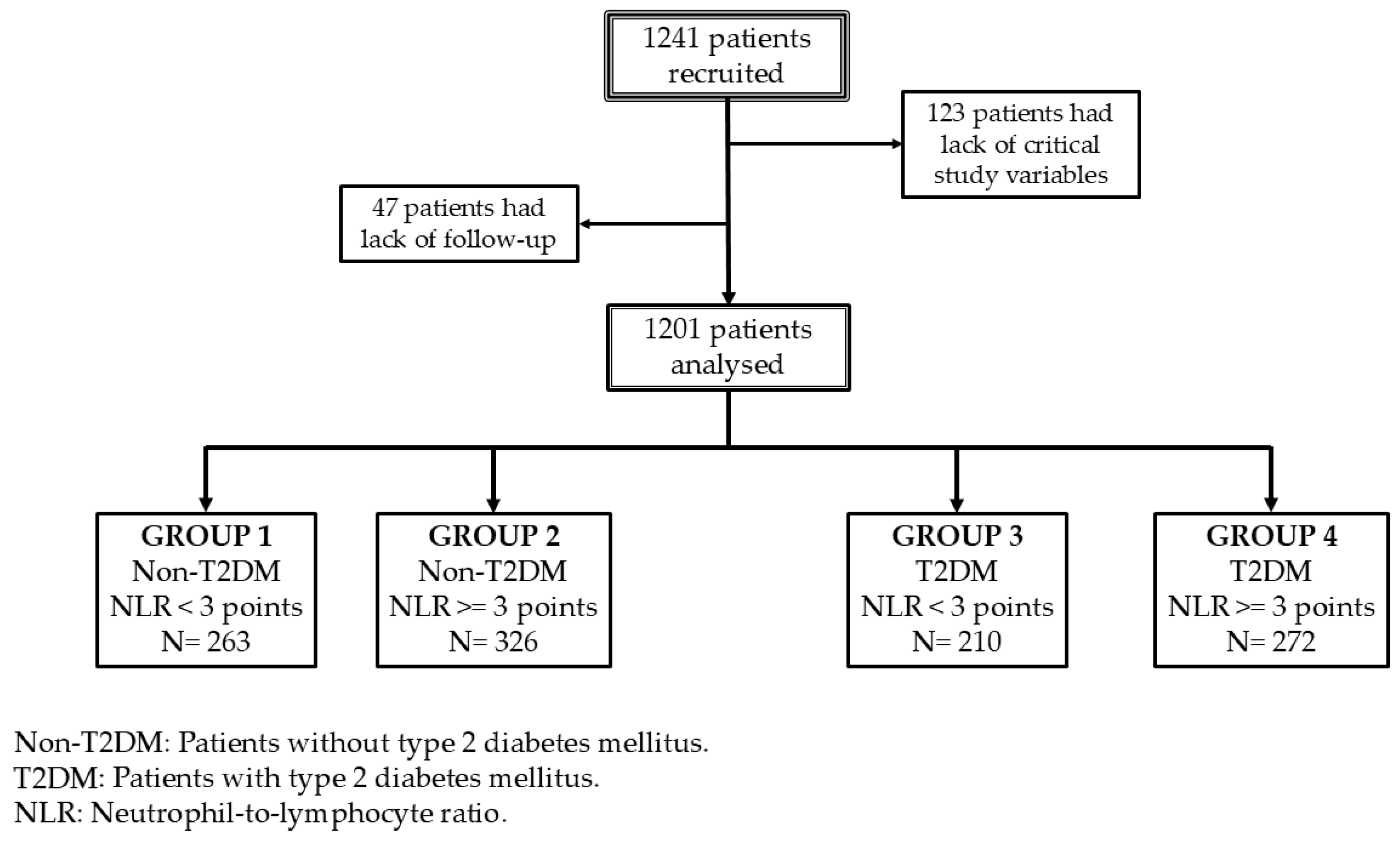

2. Methods

2.1. Variables

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benjamin, E.J.; Levy, D.; Vaziri, S.M.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Belanger, A.J.; Wolf, P.A. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 1994, 271, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, G. Glycemic variability and the risk of atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1126581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijla, F.; Buttia, C.; Reichlin, T.; Razvi, S.; Minder, B.; Wilhelm, M.; Muka, T.; Franco, O.H.; Bano, A. Association of diabetes with atrial fibrillation types: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.F.; Chen, Y.J.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, S.A. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalamandris, S.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Papamikroulis, G.-A.; Vogiatzi, G.; Papaioannou, S.; Deftereos, S.; Tousoulis, D. The Role of Inflammation in Diabetes: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Eur. Cardiol. 2019, 14, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jin, L.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, L. Inflammation in diabetes complications: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. MedComm 2024, 5, e516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohne, L.J.; Johnson, D.; Rose, R.A.; Wilton, S.B.; Gillis, A.M. The Association Between Diabetes Mellitus and Atrial Fibrillation: Clinical and Mechanistic Insights. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparelia, N.; Chai, J.T.; Fisher, E.A.; Choudhury, R.P. Inflammatory processes in cardiovascular disease: A route to targeted therapies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Cao, C.; Chen, Y.; Yi, Y.; Guo, X.; Luo, Y.; Weng, S.; Peng, D. Association of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Liu, L.; Chai, M.; Cai, Z.; Wang, D. Predictive value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for clinical outcome in patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1461923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, G.; Gan, M.; Xu, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, L. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a risk factor for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among individuals with diabetes: Evidence from the NHANES 2003–2016. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagris, M.; Vardas, E.P.; Theofilis, P.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Tousoulis, D. Atrial Fibrillation: Pathogenesis, Predisposing Factors, and Genetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arévalo-Lorido, J.C.; Alonso Ecenarro, F.; Luque-Linero, P.; García Calle, D.; Varona, J.F.; Gañán Moreno, E.; González, B.S.; Gomez, J.C.; Gullón, A.; Guerra, L.C. Profile of patients with atrial fibrillation treated in internal medicine departments in spain. SUMAMOS-FA-SEMI registry. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2025, 225, 502283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Harker, J.O.; Salvà, A.; Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M366–M372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. Functional evaluation: The barthel index. Md. State Med. J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, R. EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy 1996, 37, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Hu, T.; Wang, J.; Xiao, R.; Liao, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, Z. Systemic immune-inflammation index as a potential biomarker of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 933913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Wen, X.; Wu, S.; Cui, L. High levels of high-sensitivity C reactive protein to albumin ratio can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2023, 77, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Gu, H.; Zheng, X.; Pan, B.; Liu, P.; Zheng, M. Pretreatment C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio is Associated with Poor Survival in Patients with 2018 FIGO Stage IB-IIA HPV-Positive Cervical Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2021, 27, 1609946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lip, G.Y.; Apostolakis, S. Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Nie, J.; Cao, M.; Luo, C.; Sun, C. Association between inflammation markers and all-cause mortality in critical ill patients with atrial fibrillation: Analysis of the Multi-Parameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2024, 51, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijmeijer, R.; Lagrand, W.K.; Lubbers, Y.T.; Visser, C.A.; Meijer, C.J.; Niessen, H.W.; Hack, C.E. C-reactive protein activates complement in infarcted human myocardium. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 163, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Cervera, A.; Soehnlein, O.; Kenne, E. Neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Song, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, H. Association of inflammation indices with left atrial thrombus in patients with valvular atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barter, P.J.; Nicholls, S.; Rye, K.A.; Anantharamaiah, G.M.; Navab, M.; Fogelman, A.M. Antiinflammatory properties of HDL. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Gong, D.; Fan, Y. Impact of preexisting diabetes mellitus on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 921159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeel, S.; Motaung, B.; Nguyen, K.A.; Ozturk, M.; Mukasa, S.L.; Wolmarans, K.; Blom, D.J.; Sliwa, K.; Nepolo, E.; Günther, G.; et al. Impact of statins as immune-modulatory agents on inflammatory markers in adults with chronic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Xie, Q.; Lu, X.; Fan, R.; Tong, N. Research advances in the anti-inflammatory effects of SGLT inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 263 | 326 | 210 | 272 | |

| Age (year) | 82 (10) | 84 (10) | 82 (11) | 82 (9) | 0.001 |

| Sex (Women) | 147 (55.9) | 198 (60.7) | 97 (46.2) | 115 (42.5) | 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 (6.7) | 26.4 (7.5) | 28.4 (7.4) | 28.3 (7.9) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 98 (23.5) | 96 (35.2) | 102.5 (24.5) | 104 (31) | 0.02 |

| Hypertension (%) | 221 (84) | 264 (80.7) | 202 (96.2) | 261 (96.3) | 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 151 (57.4) | 170 (52.1) | 158 (75.6) | 205 (75.6) | 0.0001 |

| Obesity (%) | 78 (30.1) | 99 (30.6) | 80 (38.8) | 116 (43) | 0.002 |

| Tobacco user (%) | 84 (32.2) | 92 (28.3) | 73 (35.1) | 115 (42.6) | 0.019 |

| Alcohol user (%) | 43 (16.3) | 29 (8.9) | 35 (16.7) | 53 (19.5) | 0.01 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 51 (19.8) | 50 (15.3) | 56 (27.2) | 72 (26.9) | 0.0012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 47 (17.9) | 64 (19) | 36 (17.2) | 56 (20.7) | 0.88 |

| Peripheral artery disease (%) | 11 (4.2) | 25 (7.7) | 34 (16.3) | 43 (15.9) | 0.0001 |

| Heart failure (%) | 182 (69.5) | 236 (72.6) | 162 (77.5) | 225 (82.7) | 0.0021 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 94 (35.9) | 129 (39.6) | 119 (56.9) | 137 (50.9) | 0.0001 |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea (%) | 31 (11.8) | 40 (12.3) | 51 (24.6) | 70 (26.2) | 0.0001 |

| Cancer (%) | 28 (10.6) | 36 (11) | 14 (6.7) | 35 (13) | 0.04 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 5 (2) | 6 (2) | 7 (2) | 7 (3) | <0.0001 |

| MNAsf score | 10 (3) | 10 (3) | 11 (3) | 10 (3.5) | 0.001 |

| EuroQoL | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 6 (1.2) | 6 (2) | <0.0001 |

| CHA2DS2-VA score | 4 (1.5) | 4 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (1) | <0.0001 |

| HASBLED score | 3 (1) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | <0.0001 |

| Leucocyte (109/L) | 6.4 (2.7) | 8.1 (4.3) | 6.7 (2.9) | 8.5 (3.8) | <0.0001 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 3.4 (1.6) | 6 (3.9) | 3.6 (1.8) | 6.3 (3.6) | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocyte (109/L) | 1.9 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 39.7 (6.1) | 36.5 (5.9) | 39.6 (6.9) | 36.8 (6.1) | <0.0001 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 199 (86.5) | 207 (122) | 201 (82.7) | 220 (118.5) | 0.002 |

| NLR | 1.9 (0.8) | 5.7 (5.6) | 2 (0.9) | 5.8 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| CAR | 0.8 (3) | 1.8 (3.8) | 0.7 (2.6) | 1.5 (3.5) | 0.0002 |

| SII | 373.3 (228.2) | 1216 (1358.9) | 367 (201.2) | 1262.6 (1110.1) | 0.0001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/m2) | 57.4 (33.5) | 52.6 (39.1) | 44.4 (35.5) | 43.7 (33.7) | <0.0001 |

| A1C (%) | 5.6 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.6) | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.6 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 92 (21.2) | 102 (34) | 116 (46) | 122 (57.2) | <0.0001 |

| TyG index | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.3) | 4.7 (0.4) | 4.7 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 153 (50.5) | 140 (51.2) | 142 (58.7) | 128 (48) | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 45.5 (19) | 42 (16) | 43 (17) | 37 (16) | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 83 (40) | 76 (39.7) | 72 (41.5) | 66.5 (38.2) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 95.5 (58.5) | 89 (47) | 110 (66.7) | 99 (53) | 0.002 |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) | 5.9 (2.8) | 6.8 (3.5) | 6.2 (2.4) | 6.9 (3.3) | 0.008 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 3 (10.1) | 7 (12.9) | 3.4 (10.8) | 5.8 (12.8) | <0.0001 |

| Albumin/creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 83.9 (386.1) | 185.2 (519.5) | 111.7 (318.1) | 238.7 (768.4) | 0.0007 |

| Treatments at discharge | |||||

| SGLT2i | 23 (8.7) | 54 (16.1) | 43 (20.5) | 96 (35.3) | <0.0001 |

| arGLP1 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 8 (3.8) | 7 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Metformin | 0 | 5 (1.5) | 115 (54.8) | 137 (30.4) | <0.0001 |

| DPP4i | 0 | 0 | 16 (7.6) | 48 (17.7) | 0.002 |

| Insulin | 0 | 0 | 25 (11.9) | 56 (20.6) | <0.0001 |

| ACEIs | 31 (11.8) | 46 (14.1) | 19 (9) | 38 (13.9) | 0.29 |

| ARB | 45 (17.1) | 82 (25.1) | 36 (17.4) | 83 (30.5) | 0.0003 |

| Statins | 46 (17.5) | 98 (30) | 45 (21.4) | 112 (41.2) | <0.0001 |

| OACs | 106 (40.3) | 184 (56.3) | 74 (35.2) | 165 (60.7) | <0.0001 |

| MRA | 9 (3.4) | 35 (10.7) | 13 (6.2) | 32 (11.8) | 0.0001 |

| Total Mortality and Readmissions | ||||||

| Model 1: Unadjusted | Model 2: Adjusted | |||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | <0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.05 | 0.009 |

| Sex | 0.88 | 0.74–1.04 | 0.14 | 0.89 | 0.68–1.15 | 0.377 |

| BMI | 0.97 | 0.95–0.98 | 0.0008 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.863 |

| Glucose | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.489 |

| Albumin/creatinine ratio | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.003 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.262 |

| Treatment with SGLT2is | 1.32 | 1.08–1.61 | 0.005 | 1.24 | 0.91–1.68 | 0.159 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 1.14 | 1.09–1.19 | <0.0001 | 1.13 | 1.06–1.22 | 0.0003 |

| Groups | ||||||

| Group 1 | Ref. | Ref. | - | Ref. | Ref. | - |

| Group 2 | 2.16 | 1.71–2.74 | <0.0001 | 2.19 | 1.51–3.19 | <0.0001 |

| Group 3 | 1.17 | 0.88–1.54 | 0.27 | 0.92 | 0.58–1.44 | 0.729 |

| Group 4 | 1.85 | 1.45–2.38 | <0.0001 | 1.44 | 0.93–2.23 | 0.085 |

| Total Mortality | ||||||

| Model 3: Unadjusted | Model 4: Adjusted | |||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 1.06 | 1.04–1.08 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.07 | 0.002 |

| Sex | 1.03 | 0.81–1.30 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.60–1.26 | 0.48 |

| BMI | 0.97 | 0.96–0.99 | 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.46 |

| Glucose | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.4 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.73 |

| Albumin/creatinine ratio | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.71 |

| Treatment with SGLT2is | 1.15 | 0.87–1.5 | 0.32 | 1.47 | 0.97–2.23 | 0.06 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 1.23 | 1.16–1.3 | <0.0001 | 1.25 | 1.14–1.32 | <0.0001 |

| Groups | ||||||

| Group 1 | Ref. | Ref. | - | Ref. | Ref. | - |

| Group 2 | 3.03 | 2.13–4.31 | <0.0001 | 3.58 | 1.99–6.43 | <0.0001 |

| Group 3 | 1.16 | 0.74–1.81 | <0.0001 | 1.08 | 0.53–2.19 | 0.83 |

| Group 4 | 2.18 | 1.49–3.17 | <0.0001 | 1.78 | 1.00–3.28 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arévalo-Lorido, J.C.; Carretero-Gómez, J.; Molinero, A.M.; Montero-Hernández, E.; López-Sáez, J.B.; González-Anglada, M.I.; Vazquez-Ronda, M.A.; Castiella-Herrero, J.; Miramontes-González, J.P.; García-Alonso, R.; et al. The Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Diabetes and Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from the National Spanish Registry Sumamos-FA-SEMI. Diabetology 2026, 7, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7010011

Arévalo-Lorido JC, Carretero-Gómez J, Molinero AM, Montero-Hernández E, López-Sáez JB, González-Anglada MI, Vazquez-Ronda MA, Castiella-Herrero J, Miramontes-González JP, García-Alonso R, et al. The Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Diabetes and Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from the National Spanish Registry Sumamos-FA-SEMI. Diabetology. 2026; 7(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleArévalo-Lorido, José Carlos, Juana Carretero-Gómez, Alberto Muela Molinero, Esther Montero-Hernández, Juan Bosco López-Sáez, Maria Isabel González-Anglada, Miguel Angel Vazquez-Ronda, Jesús Castiella-Herrero, José Pablo Miramontes-González, Rocío García-Alonso, and et al. 2026. "The Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Diabetes and Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from the National Spanish Registry Sumamos-FA-SEMI" Diabetology 7, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7010011

APA StyleArévalo-Lorido, J. C., Carretero-Gómez, J., Molinero, A. M., Montero-Hernández, E., López-Sáez, J. B., González-Anglada, M. I., Vazquez-Ronda, M. A., Castiella-Herrero, J., Miramontes-González, J. P., García-Alonso, R., & on behalf of Sumamos-FA-SEMI Registry. (2026). The Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Diabetes and Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from the National Spanish Registry Sumamos-FA-SEMI. Diabetology, 7(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7010011