The Effect of Mineral and Organic Acid Addition on the Ethanol Organosolv Treatment of Waste Orange Peels for Producing Hesperidin-Enriched Extracts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals—Reagents

2.2. Procurement and Handling of Waste Orange Peels (WOP)

2.3. Extraction Procedure—Solvent Assay

2.4. Acid Effects

2.5. Examination of Extraction Kinetics

2.6. Assessment of Treatment Severity

2.7. Experimental Design and Treatment Optimization

2.8. Spectrophotometric Determinations

2.9. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

2.10. Data Elaboration and Statistics

3. Results

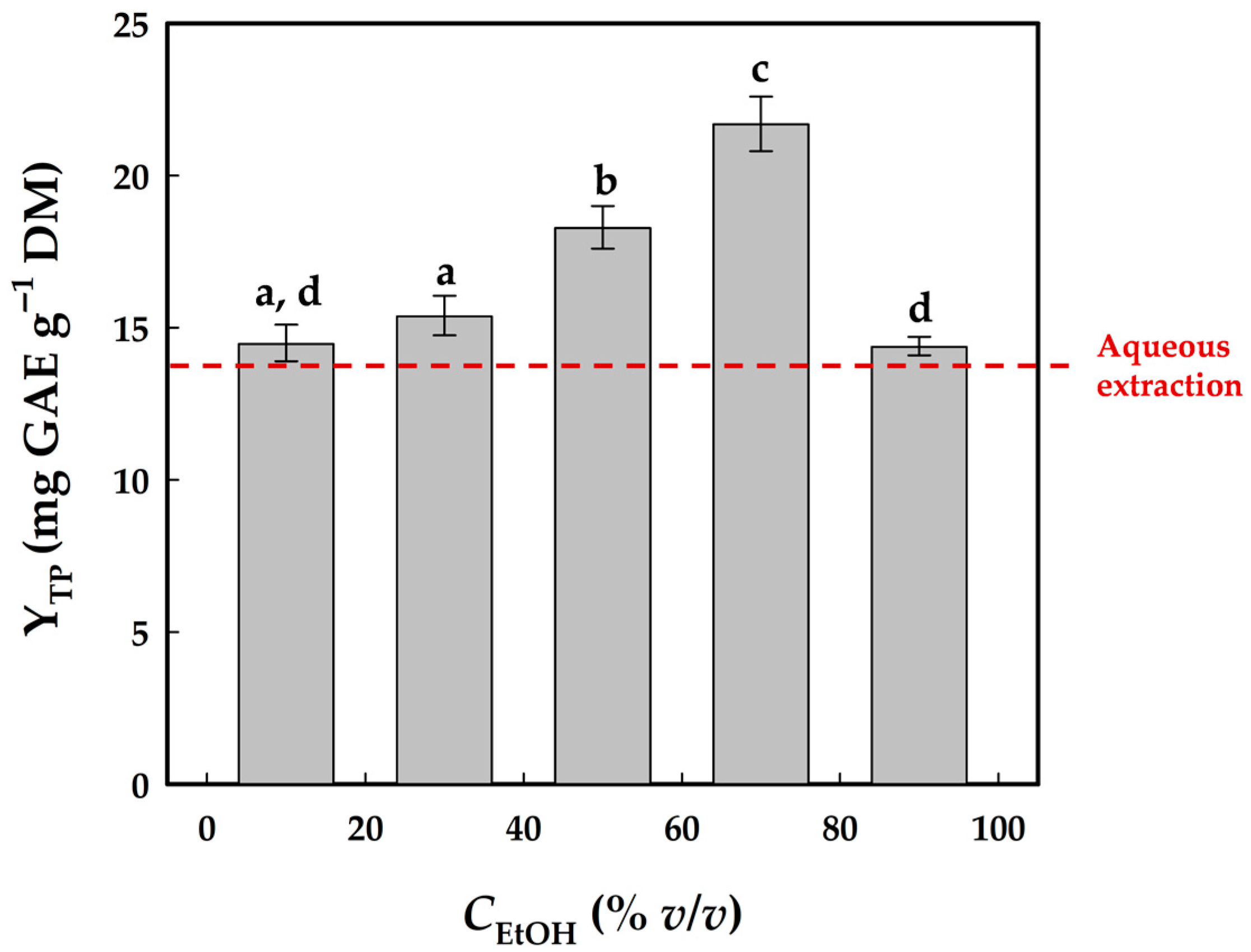

3.1. Optimum Solvent Composition

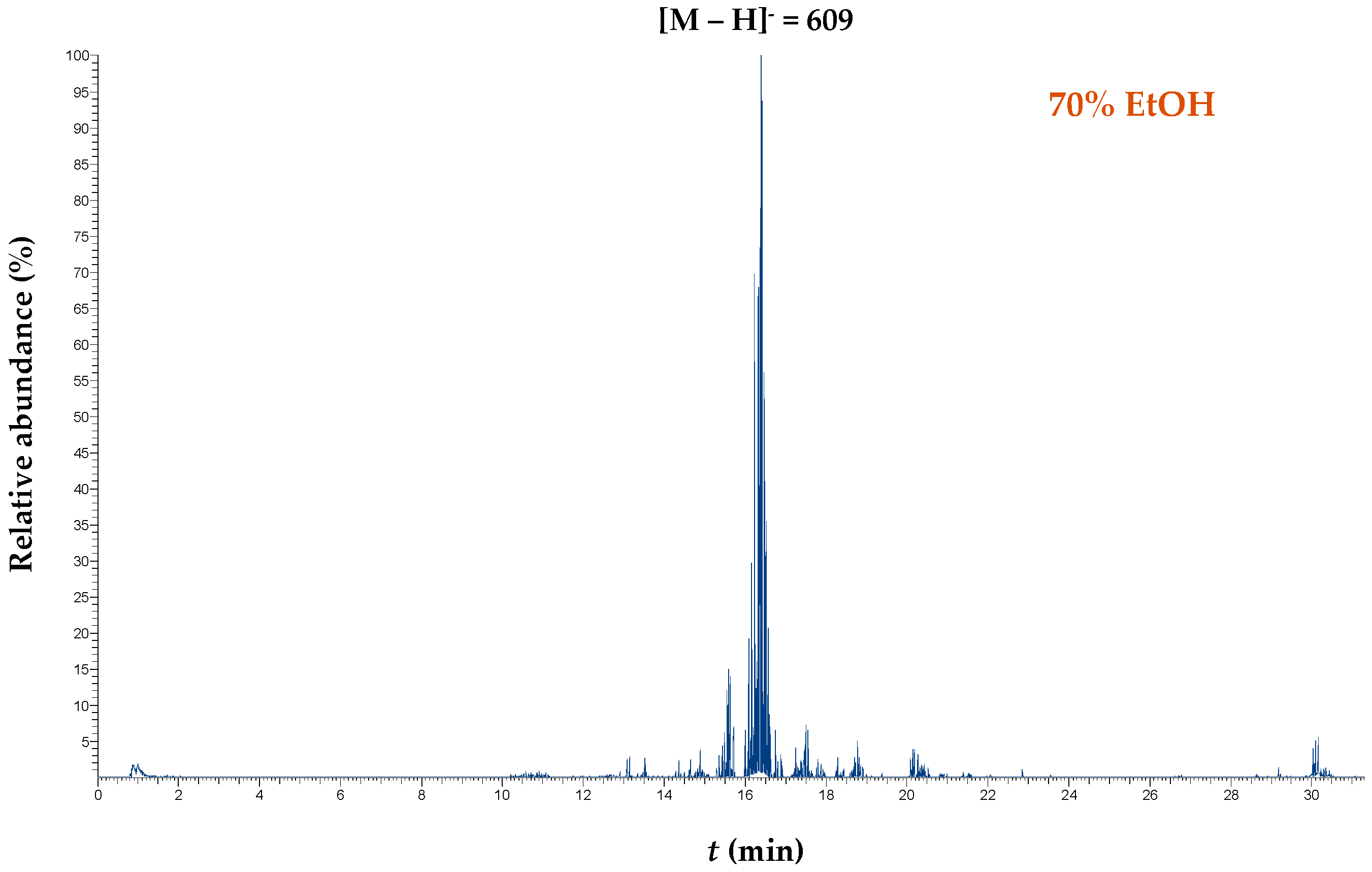

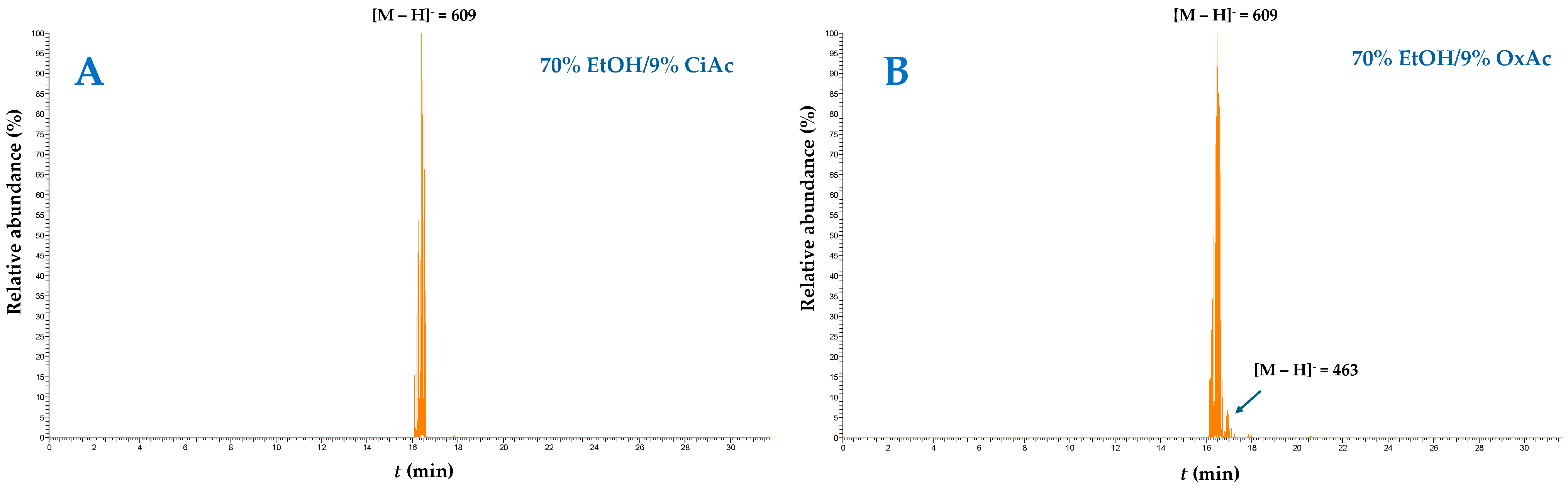

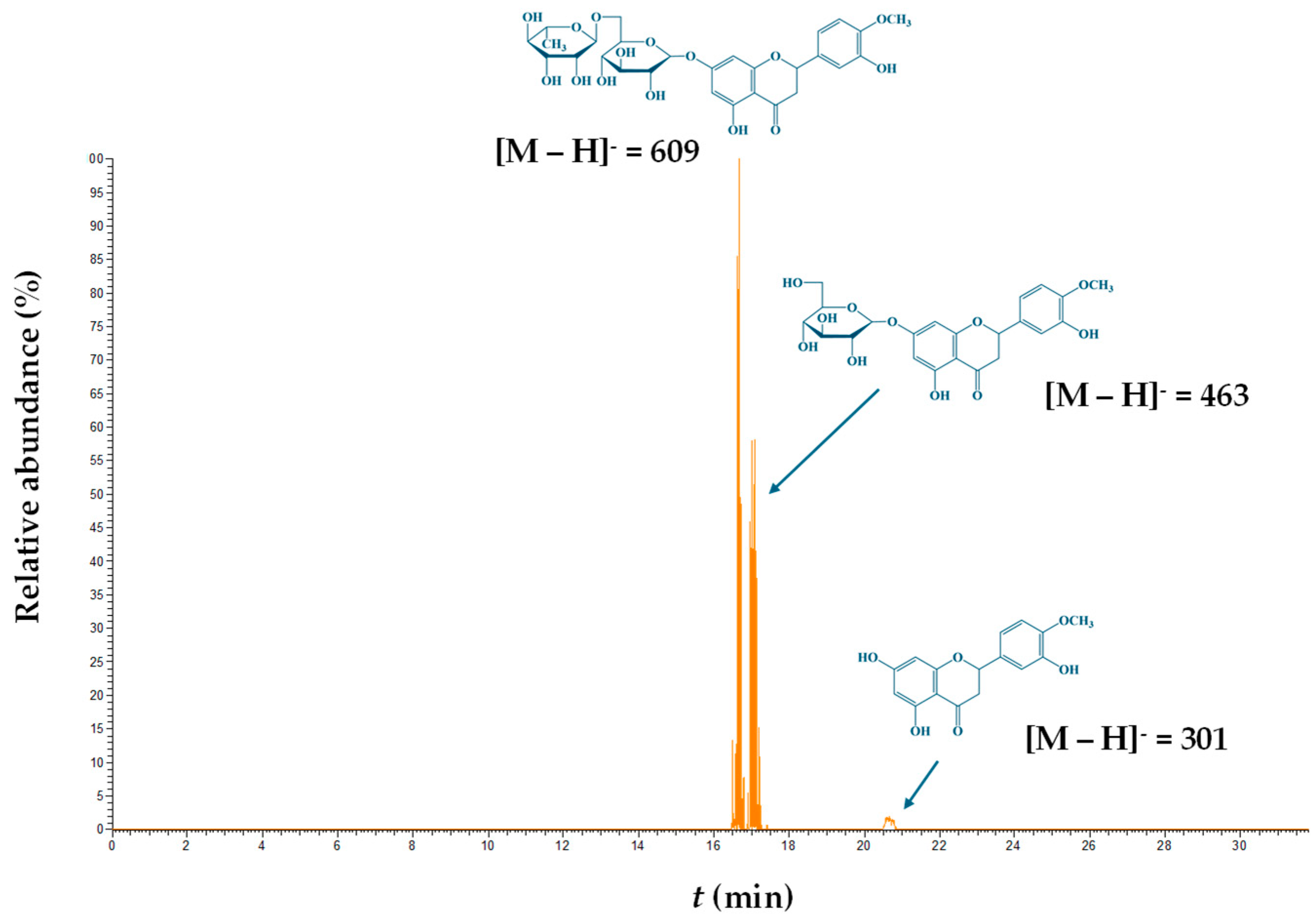

3.2. Effect of Mineral and Organic Acid Addition

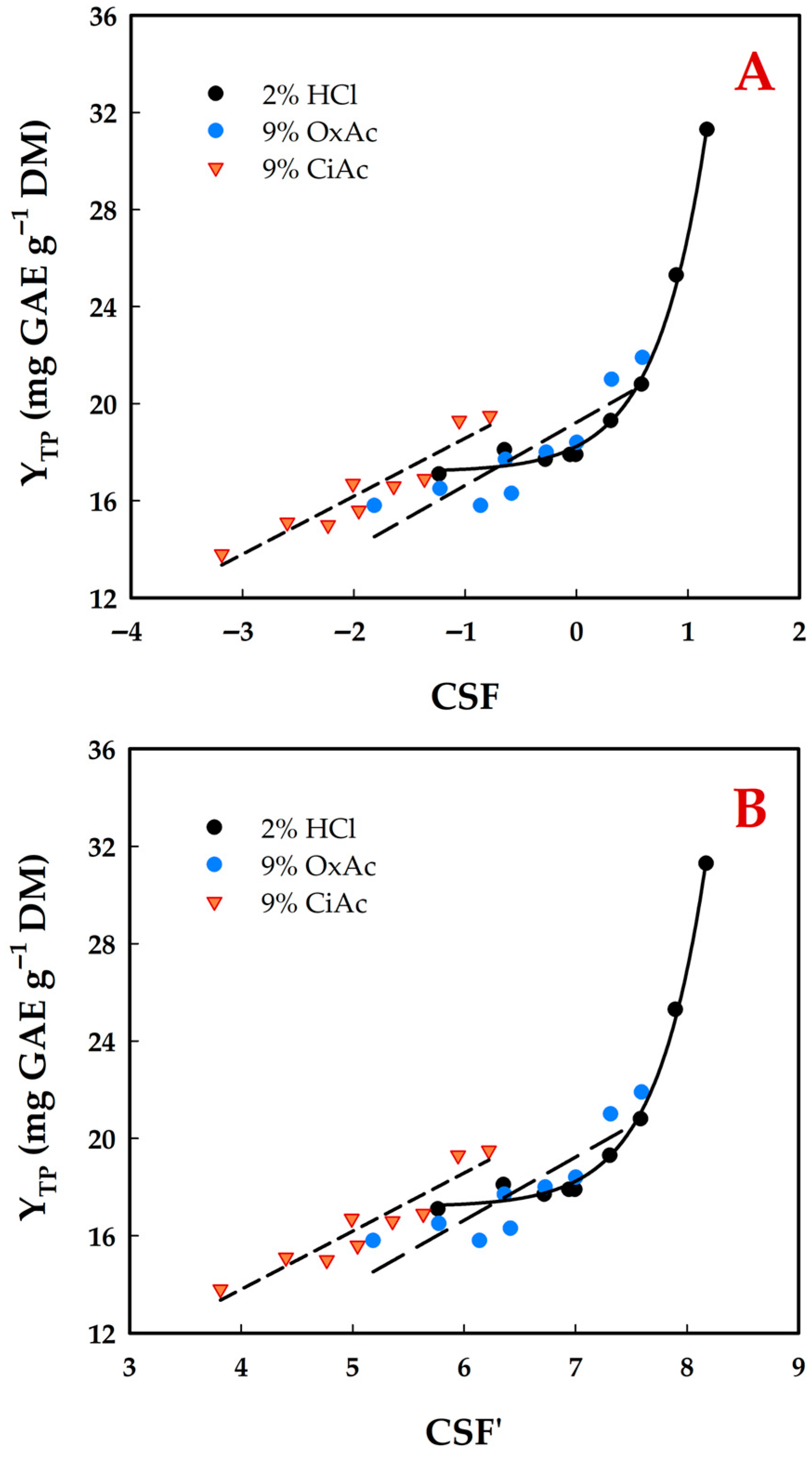

3.3. Effect of Treatment Severity

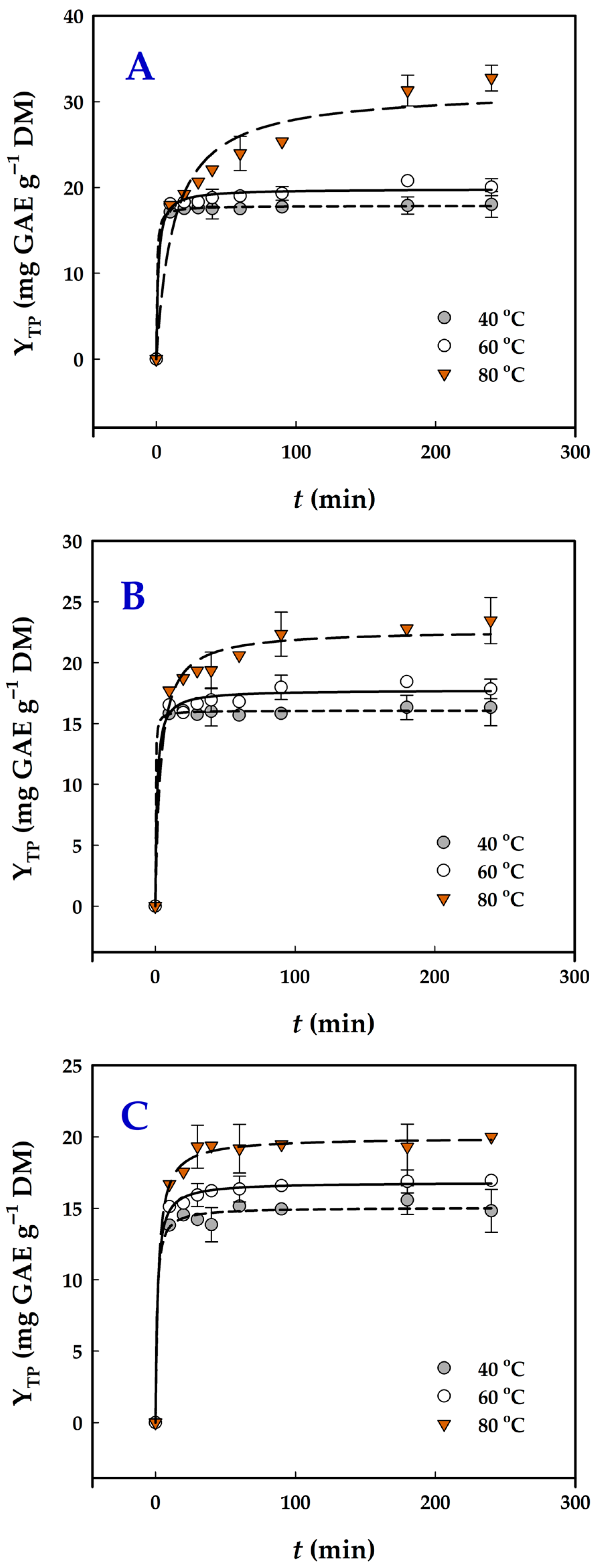

3.4. Extraction Kinetics

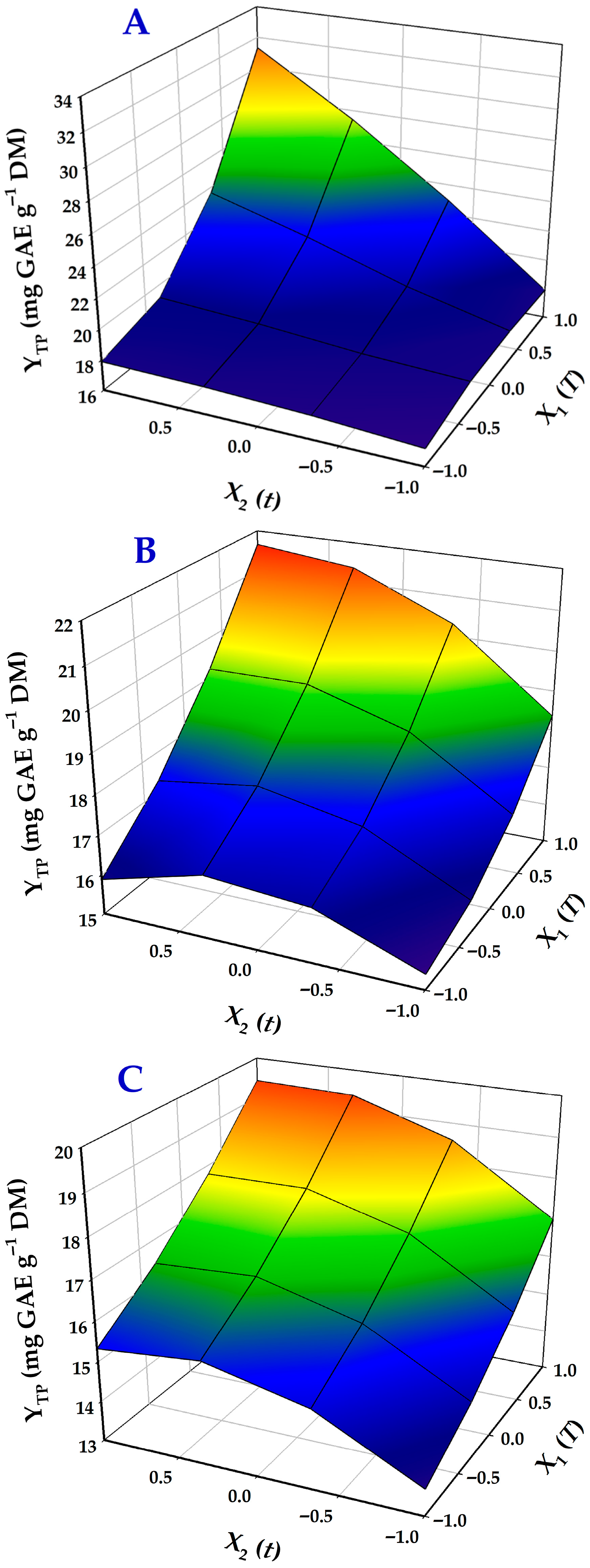

3.5. Response Surface Optimization of Treatment

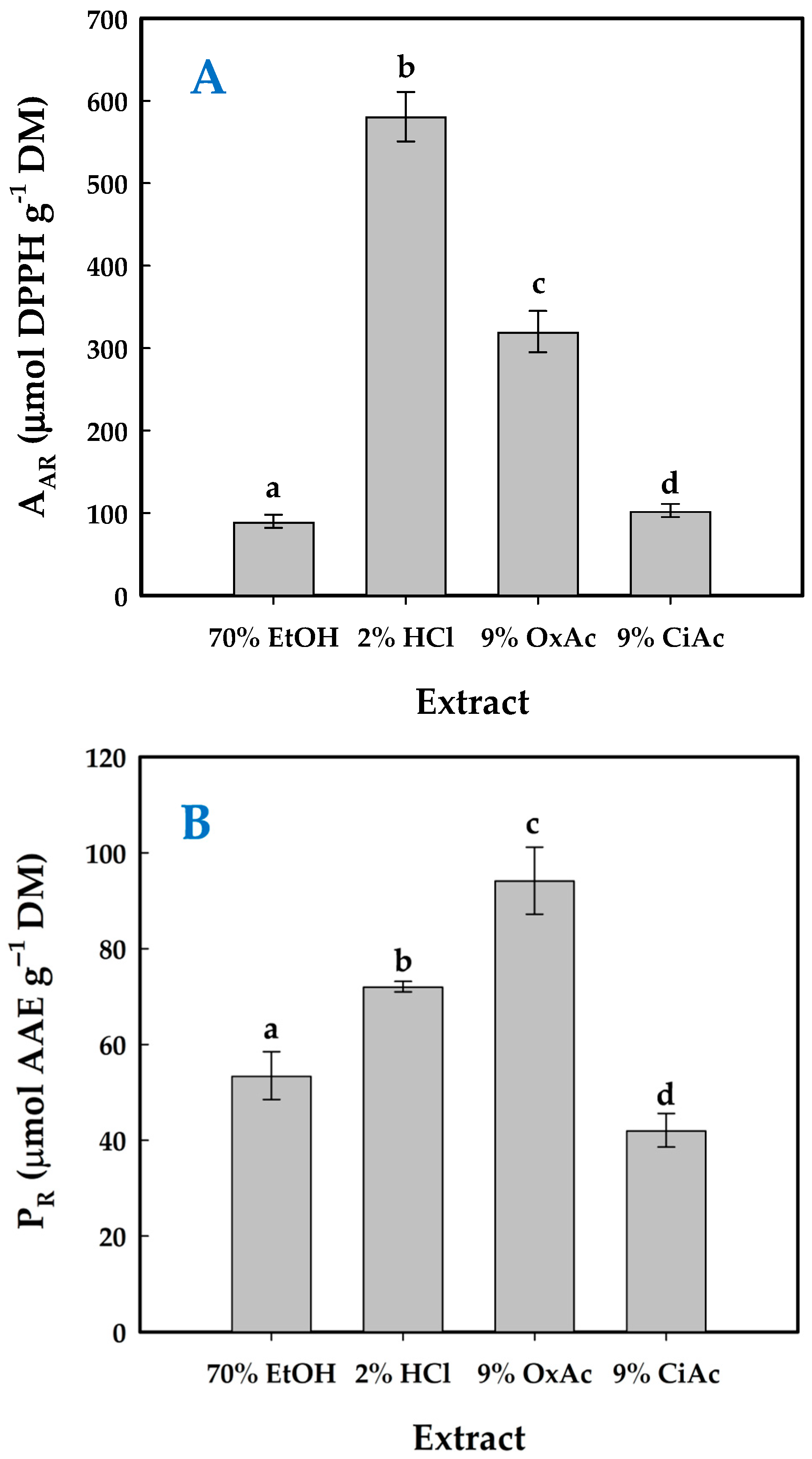

3.6. Hesperidin Yield and Antioxidant Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bakan, B.; Bernet, N.; Bouchez, T.; Boutrou, R.; Choubert, J.-M.; Dabert, P.; Duquennoi, C.; Ferraro, V.; Garcia-Bernet, D.; Gillot, S. Circular economy applied to organic residues and wastewater: Research challenges. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaashikaa, P.; Kumar, P.S.; Varjani, S. Valorization of agro-industrial wastes for biorefinery process and circular bioeconomy: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.A.; Palaniveloo, K.; Fauzi, R.; Satar, N.M.; Mohidin, T.B.M.; Mohan, G.; Razak, S.A.; Arunasalam, M.; Nagappan, T.; Sathiya Seelan, J.S. Value-added metabolites from agricultural waste and application of green extraction techniques. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.R.; Battisti, A.P.; Valencia, G.A.; de Andrade, C.J. The Production of High-Added-Value Bioproducts from Non-Conventional Biomasses: An Overview. Biomass 2023, 3, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Smith, K.H.; Stevens, G.W. The use of environmentally sustainable bio-derived solvents in solvent extraction applications—A review. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 24, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Rutkowska, M.; Owczarek, K.; Tobiszewski, M.; Namieśnik, J. Extraction with environmentally friendly solvents. Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 91, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Varatharajan, V.; Oh, W.Y.; Peng, H. Phenolic compounds in agri-food by-products, their bioavailability and health effects. J. Food Bioact 2019, 5, 57–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Camargo, A.C.; Schwember, A.R.; Parada, R.; Garcia, S.; Maróstica Júnior, M.R.; Franchin, M.; Regitano-d’Arce, M.A.B.; Shahidi, F. Opinion on the hurdles and potential health benefits in value-added use of plant food processing by-products as sources of phenolic compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Ravi, H.K. Towards petroleum-free with plant-based chemistry. Cur. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 28, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, S.; Soltanipour, F.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G.; Donsì, F. Emerging green techniques for the extraction of antioxidants from agri-food by-products as promising ingredients for the food industry. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassoff, E.S.; Guo, J.X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.C.; Li, Y.O. Potential development of non-synthetic food additives from orange processing by-products—A review. Food Qual. Saf. 2021, 5, fyaa035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Herrera, N.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G.; Robledo-Jiménez, C.L.; Rojas, R.; Orozco-Zamora, B.S. From citrus waste to valuable resources: A biorefinery approach. Biomass 2024, 4, 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Sanchez, M.; Cardona Alzate, C.A.; Solarte-Toro, J.C. Orange peel waste as a source of bioactive compounds and valuable products: Insights based on chemical composition and biorefining. Biomass 2024, 4, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, S.; Singh, A.; Nema, P.K. Recent advances in valorization of citrus fruits processing waste: A way forward towards environmental sustainability. Food Sci. Biotech. 2021, 30, 1601–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.R.; Pattnaik, F.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Meda, V.; Naik, S. Hydrothermal pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass: A review of steam explosion and subcritical water hydrolysis. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Lin, R.; Lam, C.H.; Wu, H.; Tsui, T.-H.; Yu, Y. Recent advances and challenges of inter-disciplinary biomass valorization by integrating hydrothermal and biological techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelo, M.; Arnous, A.; Meyer, A.S. Upgrading of grape skins: Significance of plant cell-wall structural components and extraction techniques for phenol release. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zietsman, A.J.; Vivier, M.A.; Moore, J.P. Deconstructing wine grape cell walls with enzymes during winemaking: New insights from glycan microarray technology. Molecules 2019, 24, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondancia, T.J.; de Aguiar, J.; Batista, G.; Cruz, A.J.; Marconcini, J.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Farinas, C.S. Production of nanocellulose using citric acid in a biorefinery concept: Effect of the hydrolysis reaction time and techno-economic analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 11505–11516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Du, H.; Liu, H.; Xie, H.; Xu, T.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Si, C. Highly efficient and sustainable preparation of carboxylic and thermostable cellulose nanocrystals via FeCl3-catalyzed innocuous citric acid hydrolysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 16691–16700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasni, S.; Guenaoui, A.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. Acid-Catalyzed organosolv treatment of potato peels to boost release of polyphenolic compounds using 1-and 2-propanol. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geropoulou, M.; Yiagtzi, E.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Makris, D.P. Organosolv treatment of red grape pomace for effective recovery of antioxidant polyphenols and pigments using a ternary glycerol/ethanol/water system under mild acidic conditions. Molecules 2024, 29, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refai, H.; Derwiche, F.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. Simultaneous high-performance recovery and extended acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of oleuropein and flavonoid glycosides of olive (Olea europaea) leaves: Hydrothermal versus ethanol organosolv treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.; Lentz, H.; Maheshwari, R. Extraction of perfumes and flavours from plant materials with liquid carbon dioxide under liquid—Vapor equilibrium conditions. Fluid Phase Equilib. 1989, 49, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgou, I.; Grigorakis, S.; Lalas, S.; Mourtzinos, I.; Makris, D.P. Incorporation of 2-hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin in a biomolecule-based low-transition temperature mixture (LTTM) boosts efficiency of polyphenol extraction from Moringa oleifera Lam leaves. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 9, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikova, I.; Simeonov, E.; Ivanova, E. Protein leaching from tomato seed––experimental kinetics and prediction of effective diffusivity. J. Food Eng. 2004, 61, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overend, R.P.; Chornet, E. Fractionation of lignocellulosics by steam-aqueous pretreatments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1987, 321, 523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, M.; Meyer, A.S. Lignocellulose pretreatment severity–relating pH to biomatrix opening. New Biotech. 2010, 27, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Ferreira, S.L.C.; Novaes, C.G.; Dos Santos, A.M.P.; Valasques, G.S.; da Mata Cerqueira, U.M.F.; dos Santos Alves, J.P. Simultaneous optimization of multiple responses and its application in Analytical Chemistry—A review. Talanta 2019, 194, 941–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicco, N.; Lanorte, M.T.; Paraggio, M.; Viggiano, M.; Lattanzio, V. A reproducible, rapid and inexpensive Folin–Ciocalteu micro-method in determining phenolics of plant methanol extracts. Microchem. J. 2009, 91, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakka, A.; Karageorgou, I.; Kaltsa, O.; Batra, G.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.; Makris, D. Polyphenol extraction from Humulus lupulus (hop) using a neoteric glycerol/L-alanine deep eutectic solvent: Optimisation, kinetics and the effect of ultrasound-assisted pretreatment. AgriEngineering 2019, 1, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulou, M.A.; Kefalas, P.; Kokkalou, E.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Papageorgiou, V.P. Analysis of antioxidant compounds in sweet orange peel by HPLC–diode array detection–electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2005, 19, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoun, R.; Grigorakis, S.; Kellil, A.; Loupassaki, S.; Makris, D.P. Process optimization and stability of waste orange peel polyphenols in extracts obtained with organosolv thermal treatment using glycerol-based solvents. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.G.; Abd El Aziz, N.M.; Youssef, M.M.; El-Sohaimy, S.A. Optimization conditions of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from orange peels using response surface methodology. J. Food Proc. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miera, B.S.; Cañadas, R.; González-Miquel, M.; González, E.J. Recovery of phenolic compounds from orange peel waste by conventional and assisted extraction techniques using sustainable solvents. Front. Biosci.-Elite 2023, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrales, F.M.; Silveira, P.; Barbosa, P.d.P.M.; Ruviaro, A.R.; Paulino, B.N.; Pastore, G.M.; Macedo, G.A.; Martinez, J. Recovery of phenolic compounds from citrus by-products using pressurized liquids—An application to orange peel. Food Bioprod. Proc. 2018, 112, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Durani, A.I.; Asari, A.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmad, M.; Yousaf, N.; Muddassar, M. Investigation of antioxidant and antibacterial effects of citrus fruits peels extracts using different extracting agents: Phytochemical analysis with in silico studies. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola-Díaz, M.d.C.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; García-Villanova, B.; Verardo, V. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction via sonotrode of phenolic compounds from orange by-products. Foods 2021, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yu, H.; Ho, C.T. Nobiletin: Efficient and large quantity isolation from orange peel extract. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2006, 20, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, M.N.; Kausar, T.; Jabbar, S.; Mumtaz, A.; Ahad, K.; Saddozai, A.A. Extraction and quantification of polyphenols from kinnow (Citrus reticulate L.) peel using ultrasound and maceration techniques. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charunivedha, S.; Aljowaie, R.M.; Elshikh, M.S.; Malar, T. Orange Peel: Low Cost Agro-waste for the extraction of polyphenols by statistical approach and biological activities. BioResources 2024, 19, 9019–9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrnakis, G.; Stamoulis, G.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Lalas, S.I.; Makris, D.P. Recovery of polyphenolic antioxidants from coffee silverskin using acid-catalyzed ethanol organosolv treatment. ChemEngineering 2023, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozinou, E.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Athanasiadis, V.; Chatzilazarou, A.; Lalas, S.I.; Makris, D.P. Glycerol-based deep eutectic solvents for simultaneous organosolv treatment/extraction: High-performance recovery of antioxidant polyphenols from onion solid wastes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazo-Cepeda, V.; Benito-Román, Ó.; Navarrete, A.; Alonso, E. Valorization of wheat bran: Ferulic acid recovery using pressurized aqueous ethanol solutions. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 4701–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazo-Cepeda, M.V.; Aspromonte, S.G.; Alonso, E. Extraction of ferulic acid and feruloylated arabinoxylo-oligosaccharides from wheat bran using pressurized hot water. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, N.; Richel, A. Adaptation of severity factor model according to the operating parameter variations which occur during steam explosion process. In Hydrothermal Processing in Biorefineries: Production of Bioethanol and High Added-Value Compounds of Second and Third Generation Biomass; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 333–351. [Google Scholar]

- Svärd, A.; Brännvall, E.; Edlund, U. Rapeseed straw polymeric hemicelluloses obtained by extraction methods based on severity factor. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M.; Engel, R.; Gonzalez-Martinez, C.; Corradini, M.G. Non-Arrhenius and non-WLF kinetics in food systems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-H.; Yusoff, R.; Ngoh, G.-C. Modeling and kinetics study of conventional and assisted batch solvent extraction. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2014, 92, 1169–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancheva, M.; Grigorakis, S.; Loupassaki, S.; Makris, D.P. Optimised extraction of antioxidant polyphenols from Satureja thymbra using newly designed glycerol-based natural low-transition temperature mixtures (LTTMs). J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2017, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakka, A.; Lalas, S.; Makris, D.P. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin as a green co-solvent in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from waste orange peels. Beverages 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, E.; Rosselló, C.; Eim, V.; Ratti, C.; Simal, S. Ultrasound-assisted aqueous extraction of biocompounds from orange byproduct: Experimental kinetics and modeling. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M’hiri, N.; Ioannou, I.; Boudhrioua, N.M.; Ghoul, M. Effect of different operating conditions on the extraction of phenolic compounds in orange peel. Food Bioprod. Proc. 2015, 96, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urios, C.; Vinas-Ospino, A.; Puchades-Colera, P.; Blesa, J.; López-Malo, D.; Frígola, A.; Esteve, M.J. Choline chloride-based natural deep eutectic solvents for the extraction and stability of phenolic compounds, ascorbic acid, and antioxidant capacity from Citrus sinensis peel. LWT 2023, 177, 114595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalompatsios, D.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Makris, D.P. Optimized production of a hesperidin-enriched extract with enhanced antioxidant activity from waste orange peels using a glycerol/sodium butyrate deep eutectic solvent. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’hiri, N.; Ioannou, I.; Ghoul, M.; Mihoubi Boudhrioua, N. Phytochemical characteristics of citrus peel and effect of conventional and nonconventional processing on phenolic compounds: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2017, 33, 587–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Mandalari, G.; Calderaro, A.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Felice, M.R.; Gattuso, G. Citrus flavones: An update on sources, biological functions, and health promoting properties. Plants 2020, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoopkumar, A.; Aneesh, E.M.; Sirohi, R.; Tarafdar, A.; Kuriakose, L.L.; Surendhar, A.; Madhavan, A.; Kumar, V.; Awasthi, M.K.; Binod, P. Bioactives from citrus food waste: Types, extraction technologies and application. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutila, A.-M.; Kammiovirta, K.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.-M. Comparison of methods for the hydrolysis of flavonoids and phenolic acids from onion and spinach for HPLC analysis. Food Chem. 2002, 76, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, F.S.; Ida, E.I. Optimisation of soybean hydrothermal treatment for the conversion of β-glucoside isoflavones to aglycones. LWT 2014, 56, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Zúñiga, J.M.; Soto-Valdez, H.; Peralta, E.; Mendoza-Wilson, A.M.; Robles-Burgueño, M.R.; Auras, R.; Gámez-Meza, N. Development of an antioxidant biomaterial by promoting the deglycosylation of rutin to isoquercetin and quercetin. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sant, A.; Ahmad, I.; Bhatia, S. Extraction and hydrolysis of naringin from Citrus fruit peels. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1263, p. 012031. [Google Scholar]

- Stabrauskiene, J.; Marksa, M.; Ivanauskas, L.; Bernatoniene, J. Optimization of naringin and naringenin extraction from Citrus × paradisi L. using hydrolysis and excipients as adsorbent. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-M.; Tait, A.R.; Kitts, D.D. Flavonoid composition of orange peel and its association with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, C.M.G.; Contesini, F.J.; Sawaya, A.C.F.; Cabral, E.C.; da Silva Cunha, I.B.; Eberlin, M.N.; de Oliveira Carvalho, P. Enhancement of the antioxidant activity of orange and lime juices by flavonoid enzymatic de-glycosylation. Food Res. Int. 2013, 52, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Lu, S.; Xing, J. Enhanced antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of citrus hesperidin by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 127539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Majo, D.; Giammanco, M.; La Guardia, M.; Tripoli, E.; Giammanco, S.; Finotti, E. Flavanones in Citrus fruit: Structure–antioxidant activity relationships. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, A.; Murakami, Y.; Shoji, M.; Kadoma, Y.; Fujisawa, S. Kinetics of radical-scavenging activity of hesperetin and hesperidin and their inhibitory activity on COX-2 expression. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 3367–3374. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Tao, Y.; Xu, T.; Wu, T.; Yu, Q.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Antioxidant activity increased due to dynamic changes of flavonoids in orange peel during Aspergillus niger fermentation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 3329–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cao, H.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Teng, H. Absorption, metabolism and bioavailability of flavonoids: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 7730–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Codes | Coded and Actual Variable Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| t (min) | X1 | 10 | 90 | 170 |

| T (°C) | X2 | 40 | 60 | 80 |

| Catalyst (% w/v) | YTP (mg GAE g−1 DM) ± s.d. |

|---|---|

| None | 21.7 ± 0.8 a |

| HCl | |

| 1 | 20.9 ± 1.2 a |

| 1.5 | 20.5 ± 1.0 a |

| 2 | 23.9 ± 1.0 b |

| Oxalic acid | |

| 6 | 21.5 ± 0.9 a |

| 9 | 21.6 ± 1.1 a |

| 12 | 18.2 ± 1.3 c |

| Citric acid | |

| 6 | 20.0 ± 1.0 a |

| 9 | 19.5 ± 0.8 a,c |

| 12 | 20.7 ± 1.4 a |

| T (°C) | t (min) | CSF | CSF′ | YTP (mg GAE g−1 DM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Catalyst | Catalyst | ||||||||

| 2% HCl | 9% OxAc | 9% CiAc | 2% HCl | 9% OxAc | 9% CiAc | 2% HCl | 9% OxAc | 9% CiAc | ||

| 40 | 10 | −1.24 | −1.82 | −3.19 | 5.76 | 5.18 | 3.81 | 17.1 ± 0.8 a | 15.8 ± 0.7 a | 13.8 ± 0.6 a |

| 90 | −0.28 | −0.86 | −2.23 | 6.72 | 6.14 | 4.77 | 17.7 ± 1.0 a | 15.8 ± 0.8 a | 15.0 ± 0.7 b | |

| 170 | −0.01 | −0.59 | −1.96 | 6.99 | 6.41 | 5.04 | 17.9 ± 0.9 a | 16.3 ± 0.7 a,c | 15.6 ± 0.7 b | |

| 60 | 10 | −0.65 | −1.23 | −2.60 | 6.35 | 5.77 | 4.40 | 18.1 ± 0.9 a,b | 16.5 ± 0.8 a,c | 15.1 ± 0.6 b |

| 90 | 0.31 | −0.27 | −1.64 | 7.31 | 6.73 | 5.36 | 19.3 ± 0.9 b,c | 18.0 ± 0.9 b | 16.6 ± 0.5 c | |

| 170 | 0.58 | 0.00 | −1.37 | 7.58 | 7.00 | 5.63 | 20.8 ± 1.1 c | 18.4 ± 0.8 b | 16.9 ± 0.7 c | |

| 80 | 10 | −0.06 | −0.64 | −2.01 | 6.94 | 6.36 | 4.99 | 17.9 ± 0.8 a | 17.7 ± 0.7 c,b | 16.7 ± 0.6 c |

| 90 | 0.90 | 0.32 | −1.05 | 7.90 | 7.32 | 5.95 | 25.3 ± 1.0 d | 21.9 ± 0.8 d | 19.3 ± 0.8 d | |

| 170 | 1.17 | 0.59 | −0.78 | 8.17 | 7.59 | 6.22 | 31.3 ± 1.4 e | 21.0 ± 1.0 d | 19.5 ± 0.7 d | |

| Catalyst | T (°C) | k (×10−3) (g mg−1 min−1) | t0.5 (min) | h (mg g−1 min−1) | YTP(s) (mg GAE g−1 DM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2% HCl | 40 | 55.87 | 0.44 | 40.68 | 17.9 ± 0.7 a |

| 60 | 38.55 | 1.31 | 15.11 | 19.8 ± 0.9 b | |

| 80 | 2.56 | 12.43 | 2.53 | 31.4 ± 1.8 c | |

| 9% OxAc | 40 | 326.90 | 0.19 | 84.74 | 16.1 ± 0.7 d,e |

| 60 | 45.67 | 1.23 | 14.47 | 17.8 ± 0.7 a | |

| 80 | 11.78 | 3.74 | 6.07 | 22.1 ± 1.0 b | |

| 9% CiAc | 40 | 64.93 | 1.02 | 14.80 | 15.1 ± 0.6 e |

| 60 | 44.09 | 1.35 | 12.44 | 16.8 ± 0.7 d | |

| 80 | 25.13 | 1.99 | 10.05 | 20.0 ± 0.9 b |

| Design Point | Independent Variables | Response (YTP, mg GAE g−1 DM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 (T, °C) | X2 (t, min) | HCl-Catalyzed | Oxalic Acid-Catalyzed | Citric Acid-Catalyzed | ||||

| Measured | Predicted | Measured | Predicted | Measured | Predicted | |||

| 1 | −1 (40) | −1 (10) | 17.1 | 17.9 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 13.8 | 13.7 |

| 2 | −1 (40) | 1 (170) | 17.9 | 17.2 | 16.3 | 15.9 | 15.6 | 15.3 |

| 3 | 1 (80) | −1 (10) | 17.9 | 18.8 | 17.7 | 18.4 | 16.7 | 17.0 |

| 4 | 1 (80) | 1 (170) | 31.3 | 30.7 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 19.3 | 19.4 |

| 5 | −1 (40) | 0 (90) | 17.7 | 17.7 | 15.8 | 16.6 | 15.0 | 15.4 |

| 6 | 1 (80) | 0 (90) | 25.3 | 24.9 | 22.3 | 21.0 | 19.5 | 19.1 |

| 7 | 0 (60) | −1 (10) | 18.1 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.3 | 15.1 | 15.0 |

| 8 | 0 (60) | 1 (170) | 20.8 | 22.1 | 18.4 | 18.2 | 16.9 | 17.0 |

| 9 | 0 (60) | 0 (90) | 19.3 | 19.4 | 18.0 | 18.2 | 16.6 | 16.9 |

| 10 | 0 (60) | 0 (90) | 19.8 | 19.4 | 17.6 | 18.2 | 17.0 | 16.9 |

| 11 | 0 (60) | 0 (90) | 18.8 | 19.4 | 18.5 | 18.2 | 17.2 | 16.9 |

| Catalyst | Equations (Models) | R2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2% HCl | 19.4 + 3.6X1 + 2.8X2 + 3.16X1X2 | 0.96 | 0.0016 |

| 9% OxAc | 18.1 + 2X1 + X2 | 0.95 | 0.0027 |

| 9% CiAc | 16.9 + 1.9X1 + X2 − 0.9X22 | 0.98 | 0.0005 |

| Catalyst | Maximum Predicted Response (mg GAE g−1 DM) | Optimal Conditions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t (min) | T (°C) | ||

| 2% HCl | 30.7 ± 2.7 | 170 | 80 |

| 9% OxAc | 21.3 ± 1.3 | 170 | 80 |

| 9% CiAc | 19.5 ± 0.7 | 144 | 80 |

| Treatment | Y (mg g−1 DM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesperidin | Hesperetin 7-O-glucoside | Hesperetin | Total | |

| 70% EtOH | 9.78 ± 1.85 | n.d. | n.d. | 9.78 |

| 70% EtOH/2% HCl | 8.30 ± 0.90 | 9.09 ± 1.36 | 3.84 ± 0.53 | 21.22 |

| 70% EtOH/9% OxAx | 9.43 ± 1.58 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | n.d. | 9.81 |

| 70% EtOH/9% CiAc | 10.83 ± 1.85 | n.d. | n.d. | 10.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agnaou, H.; Refai, H.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. The Effect of Mineral and Organic Acid Addition on the Ethanol Organosolv Treatment of Waste Orange Peels for Producing Hesperidin-Enriched Extracts. Analytica 2025, 6, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040056

Agnaou H, Refai H, Grigorakis S, Makris DP. The Effect of Mineral and Organic Acid Addition on the Ethanol Organosolv Treatment of Waste Orange Peels for Producing Hesperidin-Enriched Extracts. Analytica. 2025; 6(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgnaou, Hiba, Hela Refai, Spyros Grigorakis, and Dimitris P. Makris. 2025. "The Effect of Mineral and Organic Acid Addition on the Ethanol Organosolv Treatment of Waste Orange Peels for Producing Hesperidin-Enriched Extracts" Analytica 6, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040056

APA StyleAgnaou, H., Refai, H., Grigorakis, S., & Makris, D. P. (2025). The Effect of Mineral and Organic Acid Addition on the Ethanol Organosolv Treatment of Waste Orange Peels for Producing Hesperidin-Enriched Extracts. Analytica, 6(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040056