Effect of Submaximal-Dose Semaglutide on MASLD Biopsy-Free Scoring Systems in Patients with Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients

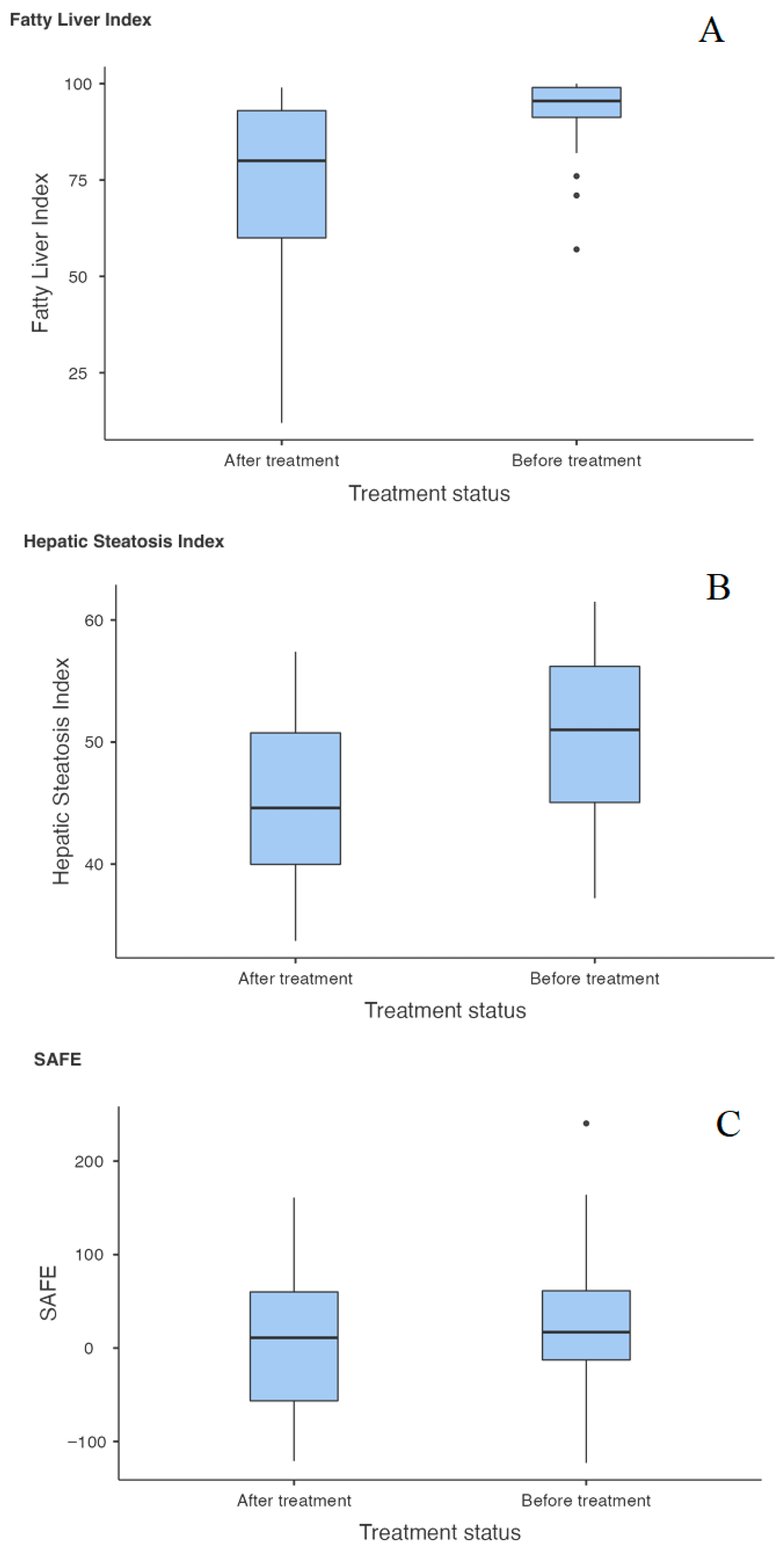

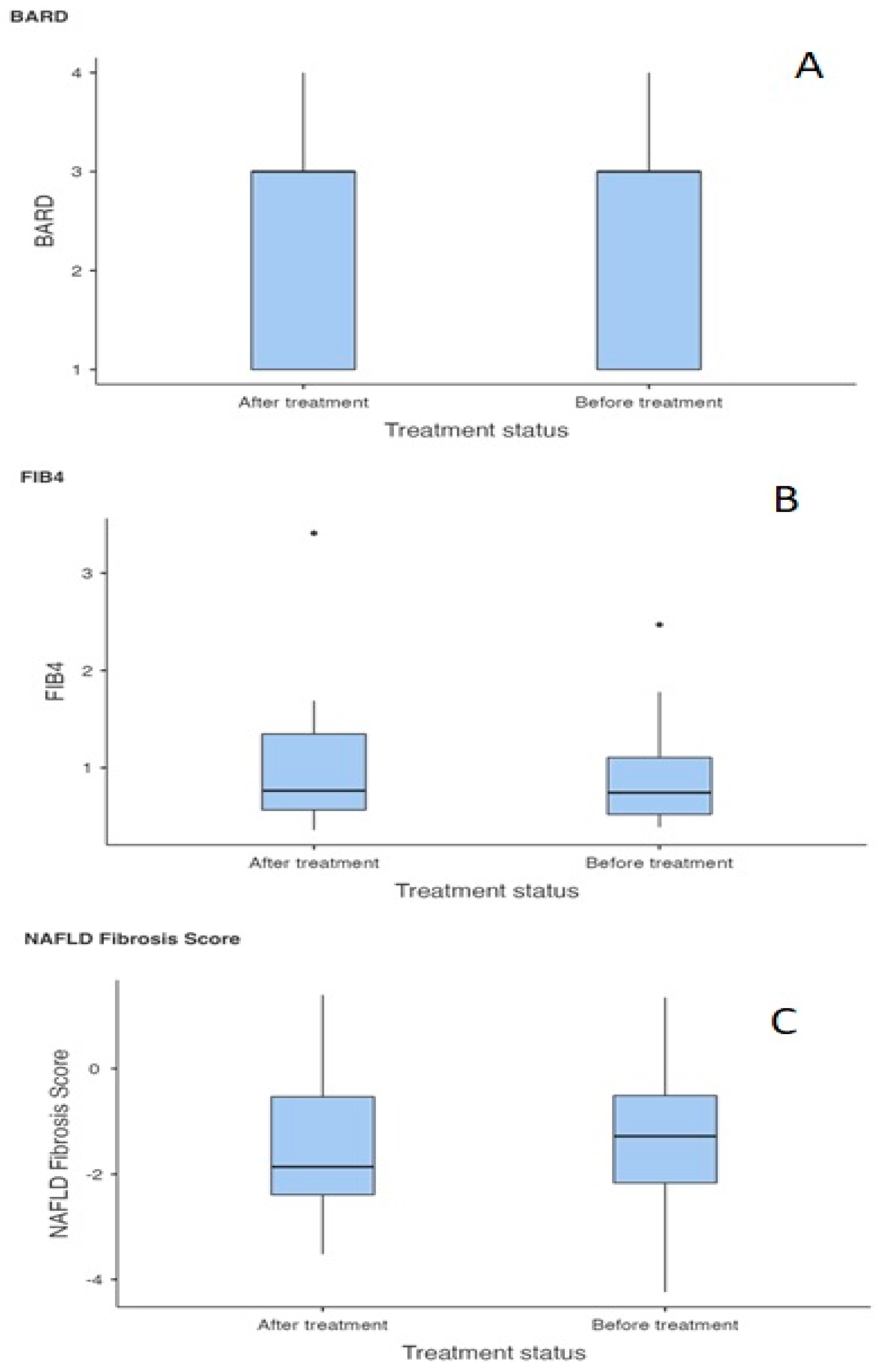

3.2. Effect of Semaglutide on MASLD NITs/BFSS

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mayoral, L.P.-C.; Andrade, G.M.; Mayoral, E.P.-C.; Huerta, T.H.; Canseco, S.P.; Canales, F.J.R.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H.A.; Cruz, M.M.; Santiago, A.D.P.; Alpuche, J.J.; et al. Obesity subtypes, related biomarkers & heterogeneity. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020, 151, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seravalle, G.; Grassi, G. Obesity and hypertension. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 122, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.N.M.S.; Sultana, H.; Nazmul Hassan Refat, M.; Farhana, Z.; Abdulbasah Kamil, A.; Meshbahur Rahman, M. The global burden of overweight-obesity and its association with economic status, benefiting from STEPs survey of WHO member states: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 46, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 492–542. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.Q.; Wong, V.W.S.; Rinella, M.E.; Boursier, J.; Lazarus, J.V.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Loomba, R. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in adults. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulchi, J.; Suryadevara, V.; Mohan, P.; Kamalanathan, S.; Sahoo, J.; Naik, D.; Selvarajan, S. Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Fatty Liver Disease: Understanding the Intricate Link. J. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 1, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, J.M.; Golabi, P.; Younossi, Y.; Mishra, A.; Younossi, Z.M. Changes in the Global Burden of Chronic Liver Diseases From 2012 to 2017: The Growing Impact of NAFLD. Hepatology 2020, 72, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. STEP 1 Study Group. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, P.J.; Zhang, V.; Gratzl, S.; Do, D.; Goodwin Cartwright, B.; Baker, C.; Gluckman, T.J.; Stucky, N.; Emanuel, E.J. Discontinuation and Reinitiation of Dual-Labeled GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Among US Adults With Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2457349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, F.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.E. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2024, 79, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddeeque, N.; Hussein, M.H.; Abdelmaksoud, A.; Bishop, J.; Attia, A.S.; Elshazli, R.M.; Fawzy, M.S.; Toraih, E.A. Neuroprotective effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists in neurodegenerative Disorders: A Large-Scale Propensity-Matched cohort study. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apperloo, E.M.; Gorriz, J.L.; Soler, M.J.; Guldris, S.C.; Cruzado, J.M.; Puchades, M.J.; López-Martínez, M.; Waanders, F.; Laverman, G.D.; van der Aart-van der Beek, A.; et al. Semaglutide in patients with overweight or obesity and chronic kidney disease without diabetes: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.; Færch, L.; Jeppesen, O.K.; Pakseresht, A.; Pedersen, S.D.; Perreault, L.; Rosenstock, J.; Shimomura, I.; Viljoen, A.; A Wadden, T.; et al. Semaglutide 2·4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): A randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Bailey, T.S.; Billings, L.K.; Davies, M.; Frias, J.P.; Koroleva, A.; Lingvay, I.; O’neil, P.M.; Rubino, D.M.; Skovgaard, D.; et al. Effect of Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo as an Adjunct to Intensive Behavioral Therapy on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, D.; Abrahamsson, N.; Davies, M.; Hesse, D.; Greenway, F.L.; Jensen, C.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rosenstock, J.; Rudofsky, G.; et al. Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, D.M.; Greenway, F.L.; Khalid, U.; O’neil, P.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Sørrig, R.; Wadden, T.A.; Wizert, A.; Garvey, W.T.; STEP 8 Investigators; et al. Effect of Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Daily Liraglutide on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity Without Diabetes: The STEP 8 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, P.N.; Sanyal, A.J.; Engebretsen, K.A.; Kliers, I.; Østergaard, L.; Vanni, D.; Bugianesi, E.; Rinella, M.E.; Roden, M.; Ratziu, V. Semaglutide 2.4 mg in Participants With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis: Baseline Characteristics and Design of the Phase 3 ESSENCE Trial. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 60, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaiel, A.; Scarlata, G.G.M.; Boitos, I.; Leucuta, D.C.; Popa, S.L.; Al Srouji, N.; Abenavoli, L.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Gastrointestinal adverse events associated with GLP-1 RA in non-diabetic patients with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 1946–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaides-Brears, H.B.; Alkhouri, N.; Allende, D.; Harisinghani, M.; Noureddin, M.; Reau, N.S.; French, M.; Pantoja, C.; Mouchti, S.; Cryer, D.R.H. Incidence of Complications from Percutaneous Biopsy in Chronic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 3366–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis—2021 update. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 659–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugianesi, E.; Miele, L.; Donnarumma, G.; Grau, K.; Mancuso, M.; Prasad, P.; Leith, A.; Higgins, V. Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Patient Characterization and Real-World Management Approaches in Italy. Pragmat. Obs. Res. 2024, 15, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Grau, A.; Gabriel-Medina, P.; Rodriguez-Algarra, F.; Villena, Y.; Lopez-Martínez, R.; Augustín, S.; Pons, M.; Cruz, L.-M.; Rando-Segura, A.; Enfedaque, B.; et al. Assessing Liver Fibrosis Using the FIB4 Index in the Community Setting. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and fibrosis progression: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 655–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.A.; Mells, J.; Dunham, R.M.; Grakoui, A.; Handy, J.; Saxena, N.K.; Anania, F.A. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is present on human hepatocytes and has a direct role in decreasing hepatic steatosis in vitro by modulating elements of the insulin signaling pathway. Hepatology 2010, 51, 1584–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mells, J.E.; Fu, P.P.; Saxena, N.K.; Anania, F.A. GLP-1 analogs reduce hepatocyte steatosis and improve survival by enhancing the unfolded protein response and promoting macroautophagy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hong, S.-W.; Kim, M.-J.; Moon, S.J.; Kwon, H.; Park, S.E.; Rhee, E.-J.; Lee, W.-Y. Dulaglutide Ameliorates Palmitic Acid-Induced Hepatic Steatosis by Activating FAM3A Signaling Pathway. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 37, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errafii, K.; Khalifa, O.; Al-Akl, N.S.; Arredouani, A. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals That Exendin-4 Improves Steatosis in HepG2 Cells by Modulating Signaling Pathways Related to Lipid Metabolism. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquette, E.; Toth, P.P.; Ramirez, G.; Cobble, M.; Chilton, R. Treatment with exenatide once weekly or twice daily for 30 weeks is associated with changes in several cardiovascular risk markers. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2012, 8, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; Franzetti, I.G.; Querci, F.; Carbone, A.; Ciccarelli, L.; Piccinni, M.N.; Fogari, E.; Maffioli, P. Exenatide plus metformin compared with metformin alone on β-cell function in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2012, 29, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Bu, R.; Yang, Q.; Jia, J.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y. Exendin-4 Protects against Hyperglycemia-Induced Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis via the AMPK-TXNIP Pathway. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 8905917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Catalán, M.; Opazo-Ríos, L.; Quiceno, H.; Lázaro, I.; Moreno, J.A.; Gómez-Guerrero, C.; Egido, J.; Mas-Fontao, S. Semaglutide Improves Liver Steatosis and De Novo Lipogenesis Markers in Obese and Type-2-Diabetic Mice with Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusilová, T.; Kovář, J.; Laňková, I.; Thieme, L.; Hubáčková, M.; Šedivý, P.; Pajuelo, D.; Burian, M.; Dezortová, M.; Miklánková, D.; et al. Semaglutide Treatment Effects on Liver Fat Content in Obese Subjects with Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Fan, J. Drug treatment for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Progress and direction. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2687–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Armstrong, M.J.; Jara, M.; Kjær, M.S.; Krarup, N.; Lawitz, E.; Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.J.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. Semaglutide 2·4 mg once weekly in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related cirrhosis: A randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoux, L.; Moszkowicz, D.; Vychnevskaia, K.; Poghosyan, T.; Beauchet, A.; Clauser, S.; Bretault, M.; Czernichow, S.; Carette, C.; Bouillot, J.-L. Effect of Bariatric Surgery-Induced Weight Loss on Platelet Count and Mean Platelet Volume: A 12-Month Follow-Up Study. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteyger, C.; Larsen, T.N.; Vercruysse, F.; Astrup, A. Effect of a dietary-induced weight loss on liver enzymes in obese subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasoyan, H.; Butsch, W.S.; Schulte, R.; Casacchia, N.J.; Le, P.; Boyer, C.B.; Griebeler, M.L.; Burguera, B.; Rothberg, M.B. Changes in weight and glycemic control following obesity treatment with semaglutide or tirzepatide by discontinuation status. Obesity 2025, 33, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, D.; Angelene, H.; Fabricatore, A.; Ard, J. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide 2.4 mg by race and ethnicity: A post hoc analysis of three randomized controlled trials. Obesity 2024, 32, 1268–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, P.; Khatri, C.P.; Nanduri, S.R.D.; Ramzan, M.; Sakalabaktula, K.S.K. Assessing the Safety of Semaglutide and Tirzepatide in Black and Asian Populations: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e87188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Patients aged 18 + years | Family history (FH) of medullary thyroid carcinoma |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | FH of MEN2 syndrome |

| MASLD | Pregnancy |

| Condition after severe/repeated pancreatitis | |

| Severe liver damage (Child Pugh-C cirrhosis) |

| Before Treatment Initiation | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Number of participants (male/female) | 30 (9M/21F) |

| Age (years) | 47 ± 14 |

| Weight (kg) | 116 ± 24.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 39.7 ± 5.78 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 120 ± 14 |

| Height/waist ratio | 0.71 ± 0.07 |

| ALT (μkat/L) | 0.59 ± 0.38 |

| AST (μkat/L) | 0.47 ± 0.20 |

| ALP (μkat/L) | 1.46 ± 0.30 |

| GGT (μkat/L) | 0.7 ± 0.50 |

| Glycemia (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 0.8 |

| Uric Acid (μmol/L) | 336 ± 63.3 |

| Triacylglycerols (mmol/L) | 1.74 ± 3.11 |

| Total serum cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.51 ± 1.06 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.25 ± 0.28 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.66 ± 0.98 |

| Total serum protein (g/L) | 73.97 ± 3.11 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.0 ± 2.64 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 31.9 ± 3.0 |

| Bilirubin total (μmol/L) | 31.9 ± 3.3 |

| Bilirubin conjugated (μmol/L) | 10.8 ± 5.68 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 9.32 ± 11.0 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 144 ± 14.2 |

| Thrombocyte count (×109/L) | 280.0 ± 51.6 |

| ARB/ACEI use (number of patients) | 6 |

| Betablocker use (number of patients) | 12 |

| Statin use (number of patients) | 5 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 135/58 ± 18/9 |

| Impaired fasting glucose (number of patients) | 11 |

| Statistic | df | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD Fibrosis Score (BT) | NAFLD Fibrosis Score (AT) | Student’s t | −0.680 | 26.0 | 0.503 |

| FLI (BT) | FLI (AT) | Student’s t | 6.450 | 28.0 | <0.001 |

| HIS (BT) | HIS (AT) | Student’s t | 8.598 | 29.0 | <0.001 |

| BARD (BT) | BARD (AT) | Student’s t | −0.682 | 29.0 | 0.501 |

| SAFE (BT) | SAFE (AT) | Student’s t | 2.249 | 26.0 | 0.033 |

| FIB4 (BT) | FIB4 (AT) | Student’s t | −1.049 | 29.0 | 0.303 |

| Parameter | Raw p | Bonferroni | Holm–Bonferroni | Benjamini–Hochberg (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLI | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| HSI | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| SAFE | 0.033 | 0.198 | 0.132 | 0.066 |

| FIB-4 | 0.303 | 1.818 | 0.909 | 0.455 |

| NAFLD Fibrosis Score | 0.503 | 3.018 | 1.000 | 0.503 |

| BARD | 0.501 | 3.006 | 1.000 | 0.503 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Focko, B.; Péč, M.J.; Miertová, Z.; Jurica, J.; Miert, A.; Kubíková, L.; Tudík, P.; Nagy, N.; Lecký, P.; Ságová, I.; et al. Effect of Submaximal-Dose Semaglutide on MASLD Biopsy-Free Scoring Systems in Patients with Obesity. Livers 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010003

Focko B, Péč MJ, Miertová Z, Jurica J, Miert A, Kubíková L, Tudík P, Nagy N, Lecký P, Ságová I, et al. Effect of Submaximal-Dose Semaglutide on MASLD Biopsy-Free Scoring Systems in Patients with Obesity. Livers. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleFocko, Boris, Martin Jozef Péč, Zuzana Miertová, Jakub Jurica, Andrej Miert, Lucia Kubíková, Peter Tudík, Norbert Nagy, Patrik Lecký, Ivana Ságová, and et al. 2026. "Effect of Submaximal-Dose Semaglutide on MASLD Biopsy-Free Scoring Systems in Patients with Obesity" Livers 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010003

APA StyleFocko, B., Péč, M. J., Miertová, Z., Jurica, J., Miert, A., Kubíková, L., Tudík, P., Nagy, N., Lecký, P., Ságová, I., Bolek, T., Havaj, D. J., Skladaný, Ľ., Mokáň, M., & Samoš, M. (2026). Effect of Submaximal-Dose Semaglutide on MASLD Biopsy-Free Scoring Systems in Patients with Obesity. Livers, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010003