Early-Stage Australian HCC Patients Treated at Tertiary Centres Show Comparable Survival Across Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan Residency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anonymous. 2023 Cancer Data in Australia; Canberra: AIHW. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/overview#rare (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Wakerman, J.; Humphreys, J.S.; Wells, R.; Kuipers, P.; Entwistle, P.; Jones, J. Primary health care delivery models in rural and remote Australia: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, B.W.; Clark, P.J.; Hartel, G.; E Powell, E.; Valery, P.C. Remoteness of residence predicts tumor stage, receipt of treatment, and mortality in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. JGH Open 2021, 5, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.L.T.; Blizzard, C.L.; Yee, K.C.; Palmer, A.J.; de Graaff, B. Survival of primary liver cancer for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in Australia. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 81, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, M.; Sanduzzi-Zamparelli, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, Á.; Díaz, A.; Llarch, N.; Iserte, G.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.; Bell, S.; Le, S.; Dev, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in Australia: Current and future perspectives. Med. J. Aust. 2023, 219, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Zhang, E.; Narasimman, M.; Rich, N.E.; Waljee, A.K.; Hoshida, Y.; Yang, J.D.; Reig, M.; Cabibbo, G.; Nahon, P.; et al. HCC surveillance improves early detection, curative treatment receipt, and survival in patients with cirrhosis: A meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Dahan, K.S.; Reczek, A.; Daher, D.; Rich, N.E.; Yang, J.D.; Hsiehchen, D.; Zhu, H.; Patel, M.S.; Molano, M.d.P.B.; Sanford, N.; et al. Multidisciplinary care for patients with HCC: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asrani, S.K.; Ghabril, M.S.; Kuo, A.; Merriman, R.B.; Morgan, T.; Parikh, N.D.; Ovchinsky, N.; Kanwal, F.; Volk, M.L.; Ho, C.; et al. Quality measures in HCC care by the Practice Metrics Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2022, 75, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, A.D.; Lubel, J.; Lam, E.; Clark, P.J.; Duncan, O.; George, J.; Jeffrey, G.P.; Lipton, L.; Liu, H.; McCaughan, G.; et al. Monitoring Quality of Care in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Modified Delphi Consensus. Hepatology 2022, 76, 3260–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmalak, J.; Lubel, J.S.; Sinclair, M.; Majeed, A.; Kemp, W.; Roberts, S.K. Quality of care in hepatocellular carcinoma-A critical review. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, M.; Cheng, A.-L.; Kokudo, N.; Kudo, M.; Lee, J.M.; Jia, J.; Tateishi, R.; Han, K.-H.; Chawla, Y.K.; Shiina, S.; et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A 2017 update. Hepatol. Int. 2017, 11, 317–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Llovet, J.M.; Yarchoan, M.; Mehta, N.; Heimbach, J.K.; Dawson, L.A.; Jou, J.H.; Kulik, L.M.; Agopian, V.G.; Marrero, J.A.; et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1922–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.; Combo, T.; Binks, P.; Bragg, K.; Bukulatjpi, S.; Campbell, K.; Clark, P.J.; Carroll, M.; Davies, J.; de Santis, T.; et al. Overcoming disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma outcomes in First Nations Australians: A strategic plan for action. Med. J. Aust. 2024, 221, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baazeem, M.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. Current status of tertiary healthcare services and its accessibility in rural and remote Australia: A systematic review. Health Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmalak, J.; Strasser, S.I.; Ngu, N.L.; Dennis, C.; Sinclair, M.; Majumdar, A.; Collins, K.; Bateman, K.; Dev, A.; Abasszade, J.H.; et al. Different Patterns of Care and Survival Outcomes in Transplant-Centre Managed Patients with Early-Stage HCC: Real-World Data from an Australian Multi-Centre Cohort Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmalak, J.; Strasser, S.I.; Ngu, N.L.; Dennis, C.; Sinclair, M.; Majumdar, A.; Collins, K.; Bateman, K.; Dev, A.; Abasszade, J.H.; et al. Initial Trans-Arterial Chemo-Embolisation (TACE) Is Associated with Similar Survival Outcomes as Compared to Upfront Percutaneous Ablation Allowing for Follow-Up Treatment in Those with Single Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) ≤ 3 cm: Results of a Real-World Propensity-Matched Multi-Centre Australian Cohort Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 3010. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmalak, J.; Strasser, S.I.; Ngu, N.; Dennis, C.; Sinclair, M.; Majumdar, A.; Collins, K.; Bateman, K.; Dev, A.; Abasszade, J.H.; et al. Improved Survival Outcomes with Surgical Resection Compared to Ablative Therapy in Early-Stage HCC: A Large, Real-World, Propensity-Matched, Multi-Centre, Australian Cohort Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.; Emery, J.D.; Roberts, S.; Thompson, A.J.; Ng, M.; George, J.; A Leggett, B.; Tse, E.; Nguyen, B.; Combo, T.; et al. Opportunities to improve surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2025, 223, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versace, V.L.; Skinner, T.C.; Bourke, L.; Harvey, P.; Barnett, T. National analysis of the Modified Monash Model, population distribution and a socio-economic index to inform rural health workforce planning. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2021, 29, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, W.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, S.; Ji, J.S.; Zou, X.; Xia, C.; Sun, K.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Changing cancer survival in China during 2003-15: A pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e555–e567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, C.A.; Karbhari, N.; Rich, N.E.; Augustine, M.; Mansour, J.C.; Polanco, P.M.; Porembka, M.R.; Wang, S.C.; Zeh, H.J.; Singal, A.G.; et al. Effect of fragmentation of cancer care on treatment use and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2019, 125, 3428–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, F.; Jan, J.; Singal, A.G.; Rich, N.E. Racial and Sex Disparities in Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the USA. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2020, 19, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysko, C.; Landi, S.; Purssell, H.; Allen, A.J.; Prince, M.; Lindsay, G.; Rodrigues, S.; Irvine, J.; Street, O.; Gahloth, D.; et al. Health inequalities in hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in the United Kingdom: A scoping review. BJC Rep. 2025, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.J.; Kim, D.; Ahmed, A.; Singal, A.K. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from more rural and lower-income households have more advanced tumor stage at diagnosis and significantly higher mortality. Cancer 2021, 127, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, A.; Ismail, A.G.M.; Fan, W.; Cheng, W.; Kontorinis, N.; Chin, J.; Kong, J.; Doyle, A.; Mitchell, T. Reduced survival for rural patients with hepatocellular carcinoma within a tertiary hospital network: Treatment equality is not enough. Intern. Med. J. 2025, 55, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, A.M.; Lupu, G.V.; Green, E.W.; Deutsch-Link, S.; Henderson, L.M.; Sanoff, H.K.; Yanagihara, T.K.; Kokabi, N.; Mauro, D.M.; Barritt, A.S. Rural-Urban Disparities in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Deaths Are Driven by Hepatitis C-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubel, J.S.; Roberts, S.K.; Howell, J.; Ward, J.; Shackel, N.A. Current issues in the prevalence, diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigg, A.J.; Narayana, S.K.; Hartel, G.; Medlin, L.; Pratt, G.; Powell, E.E.; Clark, P.; Davies, J.; Campbell, K.; Toombs, M.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. E Clin. Med. 2021, 36, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, N.; Cabrié, T.; Wheeler, E.; Richmond, J.; MacLachlan, J.; Emery, J.; Furler, J.; Cowie, B. The challenge of liver cancer surveillance in general practice: Do recall and reminder systems hold the answer? Aust. Fam. Physician 2017, 46, 859–864. [Google Scholar]

- Low, E.S.; Apostolov, R.; Wong, D.; Lin, S.; Kutaiba, N.; A Grace, J.; Sinclair, M. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and quantile regression for determinants of underutilisation in at-risk Australian patients. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 13, 2149–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, O.L.; Feng, Y.; Parikh, N.D.; Singal, A.G. Primary Care Provider Practice Patterns and Barriers to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, K.M.; Weeks, M.; Spronk, K.J.J.; Fletcher, C.; Wilson, C. Caring for someone with cancer in rural Australia. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4857–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, M.L.; Hernandez, J.C.; Lok, A.S.; Marrero, J.A. Modified Charlson comorbidity index for predicting survival after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007, 13, 1515–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppel, S.; Mathur, K.; Ekser, B.; Patidar, K.R.; Orman, E.; Desai, A.P.; Vilar-Gomez, E.; Kubal, C.; Chalasani, N.; Nephew, L.; et al. Extra-hepatic comorbidity burden significantly increases 90-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and high model for endstage liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metropolitan n = 612 | Non-Metropolitan n = 242 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 64.7 ± 11.5 | 64.4 ± 9.4 | 0.759 |

| Sex | 0.165 | ||

| Female | 124 (20%) | 39 (16%) | |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status | 0.001 | ||

| Not documented | 16 (3%) | 14 (6%) | |

| Yes | 10 (2%) | 12 (5%) | |

| No | 586 (96%) | 216 (89%) | |

| Modified Monash Model Classification | - | ||

| MM1 Metropolitan | 612 (100%) | - | |

| MM2 Regional centre | - | 51 (21%) | |

| MM3 Large rural town | - | 34 (14%) | |

| MM4 Medium rural town | - | 23 (10%) | |

| MM5 Small rural town | - | 129 (53%) | |

| MM6 Remote community | - | 2 (1%) | |

| MM7 Very remote community | - | 3 (1%) | |

| Aetiology | <0.001 | ||

| Alcohol | 76 (12%) | 48 (20%) | |

| HBV | 99 (16%) | 6 (2%) | |

| HCV | 100 (16%) | 37 (15%) | |

| MASLD | 81 (13%) | 31 (13%) | |

| Other | 32 (5%) | 15 (6%) | |

| metALD | 36 (6%) | 19 (8%) | |

| HBV/HCV | 23 (4%) | 7 (3%) | |

| HCV + SLD | 132 (22%) | 77 (32%) | |

| HBV + SLD | 33 (5%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Smoking | 0.077 | ||

| Yes | 158 (26%) | 77 (32%) | |

| CCI | 4 (3 to 6) | 5 (3 to 6) | 0.086 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.009 | ||

| Yes | 502 (82%) | 216 (89%) | |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 136 (89 to 189.5) | 119 (80 to 158) | 0.001 |

| Child–Pugh Score | 0.709 | ||

| 5 | 335 (55%) | 134 (55%) | |

| 6 | 166 (27%) | 57 (24%) | |

| 7 | 63 (10%) | 27 (11%) | |

| 8 | 27 (4%) | 15 (6%) | |

| 9 | 21 (3%) | 9 (4%) | |

| Diagnosed due to surveillance | 0.017 | ||

| Yes | 495 (82%) | 175 (74%) | |

| Tumour Burden | 0.520 | ||

| Single lesion ≤ 2 cm | 187 (31%) | 66 (27%) | |

| Single lesion > 2 cm, ≤3 cm | 153 (25%) | 61 (25%) | |

| Single lesion > 3 cm, ≤5 cm | 99 (16%) | 36 (15%) | |

| Single lesion > 5 cm | 58 (9%) | 21 (9%) | |

| Multinodular, ≤3 nodules, all ≤3 cm | 115 (19%) | 58 (24%) | |

| Managing Centre | <0.001 | ||

| Transplant Centre | 273 (45%) | 159 (66%) | |

| Initial Treatment | 0.008 | ||

| Resection | 146 (24%) | 39 (16%) | |

| Ablation | 175 (29%) | 70 (29%) | |

| TACE | 241 (39%) | 121 (50%) | |

| Other | 50 (8%) | 12 (5%) | |

| Transplantation during follow-up period | 0.752 | ||

| Yes | 31 (5%) | 11 (5%) |

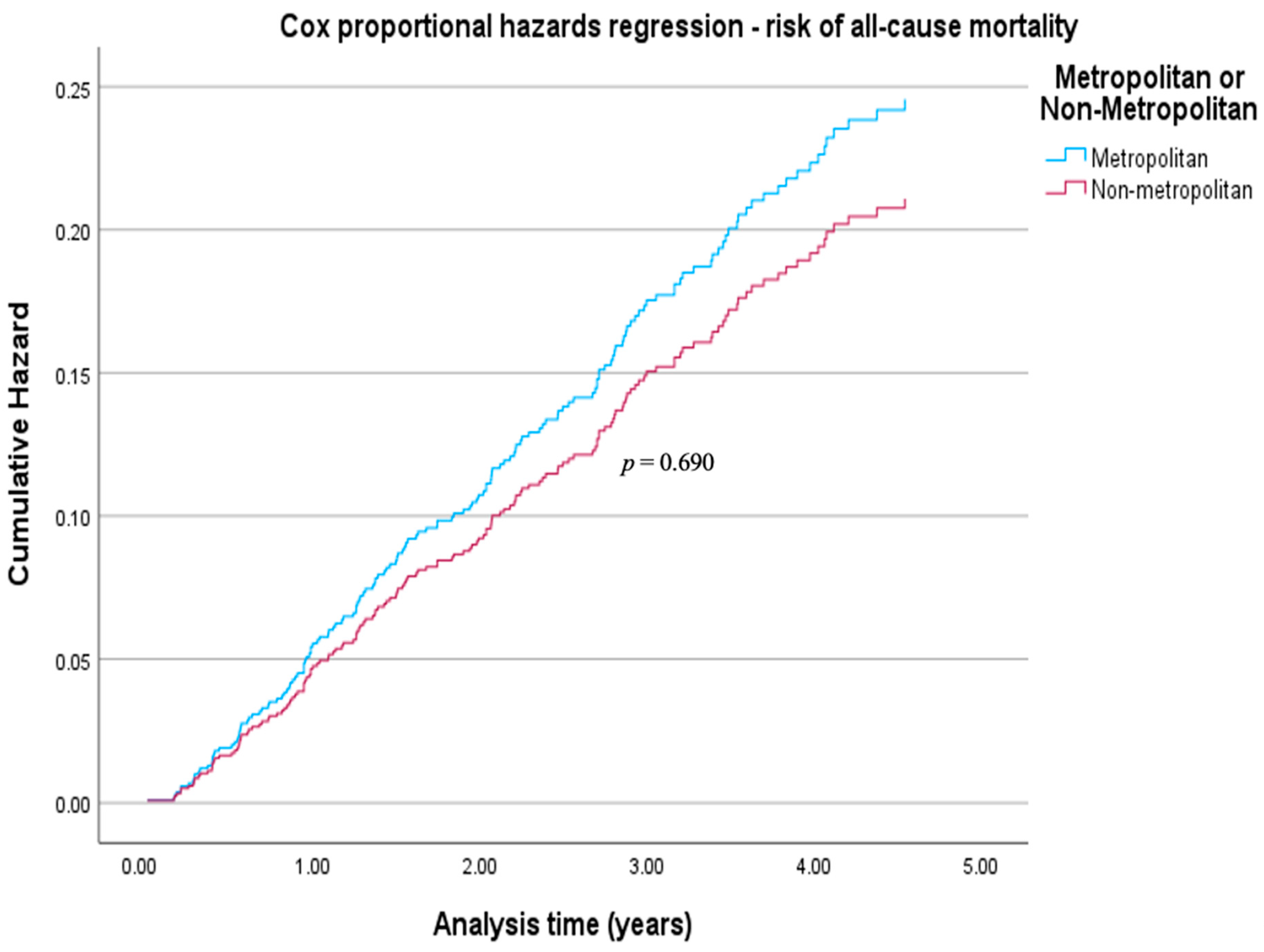

| Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | |||

| Metropolitan | Reference | - | - |

| Non-metropolitan | 0.93 | 0.64 to 1.34 | 0.690 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.574 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Reference | - | - |

| Female | 0.66 | 0.42 to 1.03 | 0.067 |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 0.92 | 0.65 to 1.32 | 0.662 |

| Tumour Burden | |||

| Single ≤ 2 cm | Reference | - | - |

| Single > 2 cm, ≤3 cm | 1.26 | 0.82 to 1.95 | 0.293 |

| Single > 3 cm, ≤5 cm | 1.41 | 0.87 to 2.30 | 0.166 |

| Single > 5 cm | 2.15 | 1.17 to 3.98 | 0.014 |

| Multinodular, ≤3 cm | 1.15 | 0.73 to 1.81 | 0.551 |

| Child–Pugh Score | 1.42 | 1.25 to 1.62 | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | |||

| No | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 1.33 | 0.74 to 2.39 | 0.335 |

| CCI | 1.18 | 1.08 to 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Platelet count | 1 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.426 |

| Alcohol | |||

| No | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 0.9 | 0.63 to 1.28 | 0.548 |

| HBV | |||

| No | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 0.93 | 0.60 to 1.44 | 0.740 |

| Smoking | - | ||

| No | Reference | - | 0.819 |

| Yes | 0.96 | 0.65 to 1.40 | |

| Managing Centre | |||

| Non-transplant centre | Reference | - | - |

| Transplant centre | 0.68 | 0.49 to 0.95 | 0.023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdelmalak, J.; Strasser, S.I.; Ngu, N.L.; Dennis, C.; Sinclair, M.; Majumdar, A.; Collins, K.; Bateman, K.; Dev, A.; Abasszade, J.H.; et al. Early-Stage Australian HCC Patients Treated at Tertiary Centres Show Comparable Survival Across Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan Residency. Livers 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010002

Abdelmalak J, Strasser SI, Ngu NL, Dennis C, Sinclair M, Majumdar A, Collins K, Bateman K, Dev A, Abasszade JH, et al. Early-Stage Australian HCC Patients Treated at Tertiary Centres Show Comparable Survival Across Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan Residency. Livers. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdelmalak, Jonathan, Simone I. Strasser, Natalie L. Ngu, Claude Dennis, Marie Sinclair, Avik Majumdar, Kate Collins, Katherine Bateman, Anouk Dev, Joshua H. Abasszade, and et al. 2026. "Early-Stage Australian HCC Patients Treated at Tertiary Centres Show Comparable Survival Across Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan Residency" Livers 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010002

APA StyleAbdelmalak, J., Strasser, S. I., Ngu, N. L., Dennis, C., Sinclair, M., Majumdar, A., Collins, K., Bateman, K., Dev, A., Abasszade, J. H., Valaydon, Z., Saitta, D., Gazelakis, K., Byers, S., Holmes, J., Thompson, A. J., Howell, J., Pandiaraja, D., Bollipo, S., ... Roberts, S. K. (2026). Early-Stage Australian HCC Patients Treated at Tertiary Centres Show Comparable Survival Across Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan Residency. Livers, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers6010002